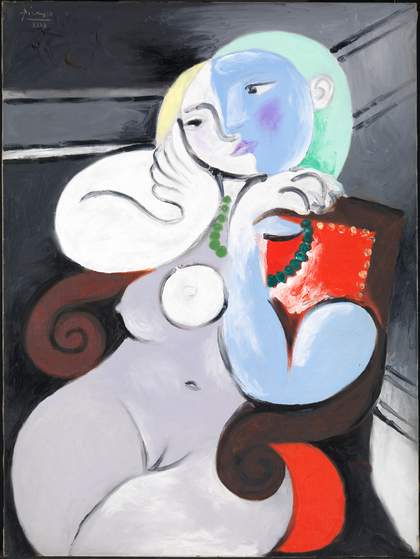

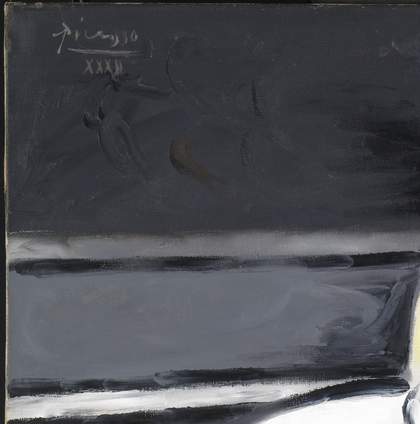

Fig.1

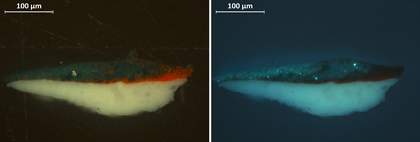

Pablo Picasso

Nude Woman in a Red Armchair 1932

Oil paint on canvas

130 cm x 97 cm

Tate N06205

© Succession Picasso/DACS London 2017

Nude Woman in a Red Armchair (fig.1) is one of a series of nudes painted by Picasso in 1932 that were inspired by Marie-Thérèse Walter, the artist’s young lover and muse, and is the only work from this series in the Tate collection. The voluptuous contours of Marie-Thérèse Walter’s body contrast sharply with contemporaneous depictions of Picasso’s wife, Olga Khokhlova, a Ukrainian ballet dancer and a member of Sergei Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes. The marriage had begun in 1918 but by the 1930s was falling apart. Picasso expressed his disillusionment by painting increasingly violent, monstrous and fragmented images of Olga Khokhlova. He painted this image in the summer of 1932 in Deauville, Normandy, where he escaped with Marie-Thérèse Walter while his wife and son were away in Juan-les-Pins.

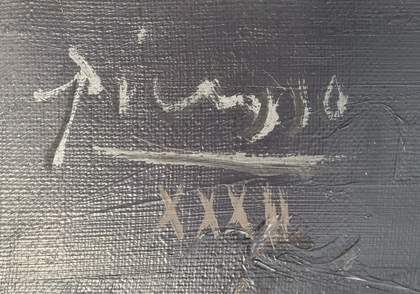

Fig.2

Detail of the inscription in Picasso’s hand on the top member of the strainer

Photo © Tate

The painting is inscribed very precisely with a date, ‘Boisgeloup 27 juillet XXXII’ (27 July 32) painted onto the stretcher bars on the reverse side (fig.2), which implies that Picasso created the painting in a single day. There is very little documentary evidence that might shed light on whether this was the case, so this article examines the structure, materials and techniques used by Picasso in the making of this work for physical evidence that might help answer the question. The painting was examined with X-radiography, infrared reflectography, transmitted and visible light, while analysis of the pigments and media were carried out to explore materials and degradation of the medium, with a view to examining the speed of execution.1

History and context

Picasso met Marie-Thérèse Walter in January 1927 on a bustling Parisian street outside a department store. In interviews in the 1970s she gave her version of this chance encounter.2 The forty-five-year-old artist invited the seventeen-and-a-half-year-old Walter to sit for him. According to Picasso expert John Richardson:

She remembered him saying: ‘You have an interesting face. I would like to do a portrait of you. I feel we are going to do great things together’. ‘I am Picasso’ he announced. The name meant nothing to Marie-Thérèse, so he took her to a bookstore and showed her a book about him – in Chinese or Japanese she thought.3

A passionate relationship ensued, which lasted nine years. In the beginning Picasso had to keep the affair secret as he was still married, increasingly unhappily, to Olga Khokhlova, and Marie-Thérèse Walter was below the age of consent. Images of his secret muse began to emerge in 1931 and from the early spring to the autumn of 1932, at his studio in the Château de Boisgeloup in Normandy, he produced a series of canvases inspired by her as his model and muse. Many of these images are inscribed with a very precise date, like this painting.4

Photographs of Marie-Thérèse Walter reveal a young woman of athletic build, with short blonde bobbed hair, swept to one side in a parting, a strong, classical profile and very blue eyes. Her physical characteristics, although somewhat idealised and sexualised in many of Picasso’s images of her, are still recognisable, making it easy to identify these works as portraits.

In Nude Woman in a Red Armchair the voluptuous body is depicted as a series of sensuous curves, softly filling the space afforded by the chair. The scrolled arms of the armchair echo the curvaceous shapes. Her pale body shines like a light out of the grey and black background. Black lines recede diagonally into what could be a corner of the walls, providing an approximation of depth to the setting. She is held in the bright red cocoon of the armchair, which provides both contrast and colour, while the straight lines of the wood suggest solidity against her pliability. The brass tacks in the upholstery also give the impression of cold, hard points against the smooth red fabric and the softness of her flesh. The way Picasso depicts the left arm as floating and partially dislocated from the body gives the impression that the chair is almost part of her physical presence. The painting appeals particularly to the viewer’s sense of touch as well as having a visual sensuality.

Technical analysis of the painting

There is good evidence to suggest that the strainer is original to the work: the first attachment of the canvas to the strainer is still intact. This is particularly relevant to the authenticity of the inscription on the reverse of the strainer (fig.2), and indicates that it applies to the painting in question and has never become dislocated from it.

The precise dating of the work gives this painting a particular place among the large number of paintings Picasso produced in 1932, but the significance of this is discussed elsewhere.5 It is not known definitively if this is the date when the painting was started, finished, or indeed whether the whole painting, from conception to final brushstroke, was carried out on that day. However, it is important to establish that the date does correspond to the work attached to the stretcher.

Fig.3

Reverse of Nude Woman in a Red Armchair 1932

Photo © Tate

Fig.4

Detail of lower strainer bar with stamp ‘60 F’ applied upside-down

Photo © Tate

It is interesting to note that the painted writing goes underneath the canvas foldover at the top and that there are no signs of black paint residue on top of the canvas (see in particular the ‘l’ in ‘Boisgeloup). Although this paint was not analysed, the date and the inscription of ‘Boisgeloup’ appear to have been executed in the same black paint. This suggests that Picasso painted the words onto the strainer before the canvas was stretched. Alternatively it is possible that Picasso lifted the edge of the stretched canvas to paint the words. The inscription appears to be rapidly executed and one might expect the boldly applied paint to have transferred onto the canvas if it had already been in place. It would be necessary to examine more paintings from this period to ascertain whether writing running under stretched canvas like this is unusual. On a 2016 visit to the studio at Boisgeloup Tate curator Achim Borchardt-Hume observed that there were several empty strainers lying around the studio with the word ‘Boisgeloup’ inscribed, without a date.6 Perhaps it was Picasso’s studio practice to annotate the strainers with the studio name when he bought them and then to add dates as he was about to use them, before the canvas was applied. The canvas is on a six-membered strainer made of softwood (fig.3), which bears the stamp ‘60 F’ on the lower strainer bar, upside down (fig.4). This is a French standard-sized strainer supplied by artists’ colourmakers.7

Fig.5

Detail of lower left corner of strainer showing nails

Photo © Tate

Fig.6

Detail of tacking margin at right side

Photo © Tate

Picasso ordered thirty-seven canvases in June 1932, and on 5 July he ordered another thirty-six canvases and strainers of different sizes (numbers 100, 80, 60, 40, 30 and 25).8 Earlier orders in 1931 describe them as ‘toiles chassis clef’, which translates as ‘keyed stretchers’, which might mean an adjustable stretcher.9 This strainer is quite typical of many seen on paintings by Picasso around this time. The joints are simple lap joints, fixed at all four corners with four nails from the reverse (fig.5). The canvas is attached with ferrous tacks and the edges of the canvas have been quite roughly cut, possibly with scissors. The attachment is original, because there are no additional tack holes and the cusping is in keeping with the points of tension provided by the current tacks (fig.6).10 The tiny holes visible alongside the tacks are perhaps what remains of a simple ‘baguette’ frame made from battens of wood attached to the foldover edges with tacks.

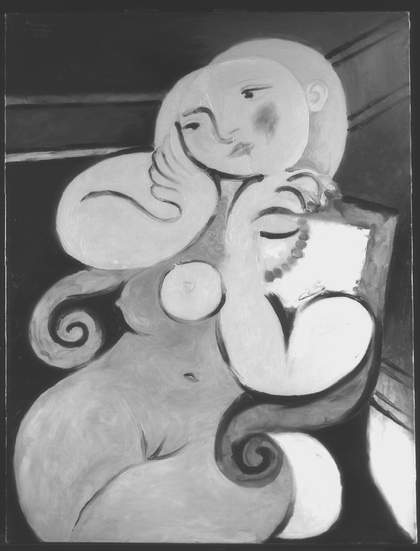

Fig.7

Infrared reflectogram of Nude Woman in a Red Armchair 1932 (1100–1700nm)

Image: Aviva Burnstock and Silvia Amato

The ground on the canvas is white, and analysis identified it as a single layer of lead white in drying oil, with very few lead soap aggregates yet formed in the course of natural ageing. This is commensurate with a commercially prepared French colourmaker’s canvas. The ground plays an important aesthetic role in the painting, since Picasso left it exposed between passages of paint. In the infrared reflectogram (fig.7) there is no sign of graphite pencil or charcoal drawing beneath the paint. Instead, outlines of thinly applied, dry, brushed dark grey or black are evident where the ground has been left visible, around the contours of the face and the fingers of the raised proper right hand, for example.

The infrared reflectogram also indicates that there were no compositional changes, and suggests the surface was painted with adjacent islands of colour that each form a single layer, with the possible exception of the scroll of the chair over the thigh of the figure, on the proper left side. This indicates that it was painted rapidly, alla prima, and with great assurance. There does not appear to be a pencil underdrawing.11

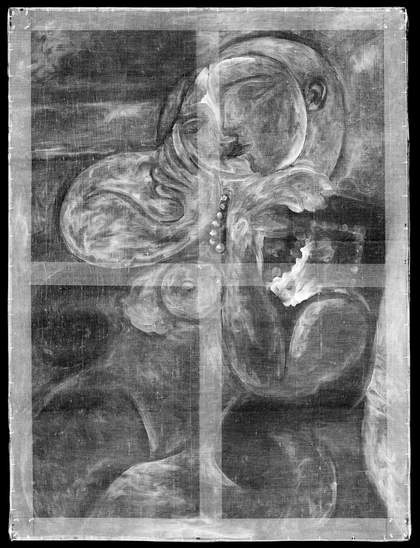

Fig.8

X-radiograph of Nude Woman in a Red Armchair 1932

Photo © Tate

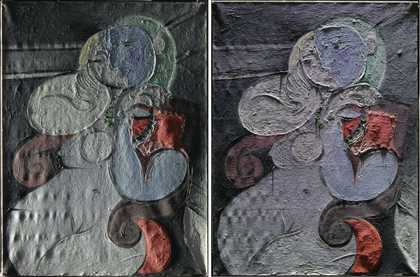

Fig.9

Nude Woman in a Red Armchair 1932 in transmitted light

Photo © Tate

The X-radiograph (fig.8) tells a similar story to the infrared image, the evidence consisting more of absence than of presence. It reveals no image beneath the current composition and shows a bare minimum of paint, apart from the thicker areas of white in the face, torso and highlights. It also reveals the four nails in each corner of the strainer and the single tack in the foldover edges, which correspond to the cusping patterns in the fabric support.

The transmitted light image (fig.9), taken with strong lighting behind the canvas, highlights the thinness of the paint. The ground remains visible around the face, where the blank areas have been filled in with yellow paint including zinc white and cadmium yellow for one section of the hair, and green made from emerald green and zinc white for the other. A border of bare ground is visible around these islands of colour. The flesh of the nude is so very thinly painted that almost every brushstroke is visible in transmitted light. The areas most loaded with paint appear to be in the black and grey background, the heavy impasto of the green beads, and the thickly applied white in the red of the chair.

Fig.10a

Micrograph of gap between the face and yellow hair where the fingers meet the face, showing grainy grey particles in paint

Photo © Tate

Fig.10b

Micrograph of the inner corner of the proper right eye in the white face, showing grainy grey paint

Photo © Tate

Fig.10c

Micrograph of grainy grey paint at the top of the ear, showing traces of green

Photo © Tate

Fig.10d

Micrograph of the marbled paint in the eyeball

Photo © Tate

Picasso seems to have planned and executed his composition entirely with paint. Grey sketchy lines are visible in the gaps around the face, and defining the outlines of the eyes and ear (figs.10a–d). He used a grainy pigment in wet paint to create the outlines of the features. The grains resemble charcoal particles caught up in the wet paint, and are not particularly well mixed. Picasso used dry charcoal with wet paint in later works made in Antibes in 1946, when he apparently used the spent filament from the carbon-arc lights used for the terrace at night.12 In a 2011 study of the (later) works at Antibes, another method of working with charcoal was examined: ‘Other grays are obtained by Picasso with ad hoc mixing of white paint and crushed charcoal, either in a can or by directly painting over charcoal lines with fluid paint, which becomes gray by incorporation of the lifted charcoal’.13 The description of this later working technique seems to fit the technique observed in the 1932 painting, of which there are no eye-witness accounts. Analysis suggested carbon black in zinc white.14 It is interesting to note that the grey grainy paint seems to skip over the peaks of the canvas without saturating the valleys, which implies that it was applied with a relatively dry brush. The proper right eye within the white face (fig.11) was painted sparingly with grey outlines of this grainy grey paint, then black and white paint was added wet-in-wet in assured sweeps of the loaded brush. The black of the eye was painted in one stabbing brushstroke which then tapers off to the left. The white was added wet-in-wet to create a swirled and marbled highlight. The proper left eye and eyebrow were created by the removal of surface paint to expose grey underneath (fig.12). The eyebrow in particular was scraped into the wet blue paint rather than painted on and there is a small semi-circular incision to the right of the pupil in the white of the eye which helps to define the sphere of the eyeball.

Fig.11

Micrograph of the proper right eye, showing sketchy grey paint

Photo © Tate

Fig.12

Detail of the proper left eye and eyebrow in transmitted light

Photo © Tate

Fig.13

Detail of the ear in transmitted light

Photo © Tate

Fig.14

Micrograph of the earlobe

Photo © Tate

The ear was also painted in this sparing and efficient way. The grey outlines were painted directly on the ground, which is obvious in transmitted light (fig.13). The white was added in several loaded brushstrokes, picking up some of the grey from the underlayers with impunity. The final flourish was an impasted earlobe, applied as one heavily loaded brushstroke which was lifted off to leave peaks of paint (fig.14). The thinly painted grey was left uncovered by the green, which was also painted up to its border.

Fig.15

Detail of the woman’s face

Photo © Tate

The woman’s face (fig.15) is an example of the double or ‘metamorphic’ image, which is often found in Picasso’s work of this time.15 It can be read as two faces, joined by a kiss at the lips. The white half is facing forward, with the eye coyly addressing the viewer. The blue face is in profile and the eye is looking intently at the other feminine face. The blue side is more thickly painted than the white and has Marie-Thérèse Walter’s classical profile.

Fig.16

Detail of the woman’s face in transmitted light viewed from reverse

Photo © Tate

It is instructive to view the face from the back of the canvas with transmitted light (fig.16). The painting is translucent where it is painted most thinly and the light shines through these areas. From the reverse, the blue head looks darker, more male and dominant and the white face (unfortunately partially obscured by the strainer bar) looks as though it is being kissed, the lips meeting in the middle. It also shows that the blue was applied directly to the ground rather than applied over the white. This is another example of adjacent islands of colour merging rather than layers of paint on top of one another, which would have been expeditious if speed were of the essence.

Figs.17a–b

Detail of lips in visible light and raking light

Photo © Tate

The lips were painted using a minimum quantity of paint on top of the wet white paint of one half of the face and the wet blue paint on the other half (figs.17a–b). Picasso added a loaded brush of purple paint and allowed the colours to mingle, shaping the lips with the brush, wiping away wet paint in the open gap between the lips, and instead of one long brushstroke, he broke it into short strokes which end with a flourish of impasto peaks at the upper corner. The point where the two halves of the lower lip meet in the middle is defined with a swirl of purple and blue paint, wet-in-wet, a true merging of the two profiles. The purple paint was identified as cobalt violet and zinc white.

Figs.18a–b

Nude Woman in a Red Armchair 1932 under raking light from left and from top

Photo © Tate

Images in raking light (figs.18a–b) reveal a detailed surface profile of all the lively brushwork, impasto, and imperfections of plane. The slight undulations in the canvas plane and the pronounced cusping at the edges with slight lines of tension in the corners are all in keeping with a painting on its original non-extendable strainer. The scalloping (visible along the top edge, for example) is compatible with the location of the ferrous tacks in the foldover edges. Although pronounced in this extremely raking light, the planar distortions are scarcely visible in normal light. Picasso painted the majority of the figure in one flat, thin, fast-drying layer, but then created the areas of lively interest with thicker paint. The majority of this textural interest is, as one might expect, concentrated around the head and upper body.

Figs.19a–b

Detail of dark green beads in visible light and under raking light from left

Photo © Tate

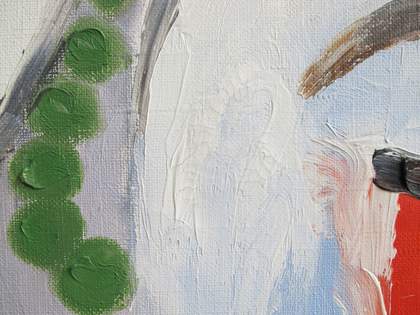

Fig.20

Cross-section showing red and green paint from the darker beads in visible light (vis) and ultraviolet light (uv)

Photo © Tate

Image: Fotini Koussiaki

The heaviest impasto is found in the green beads which adorn the figure’s neck (fig.19a). Each was begun with one twist of the paint brush in a flat circular shape, using very dark paint applied over the red of the chair. The brush was applied with some force, evidenced by a slight dent in each bead in raking light (fig.19b). On top of the flat circles, impasto in dark green and white was mixed on the canvas to create the swirling marbled effect. Fig.20 shows the wet-in-wet mingling of the red and green paint in cross-section. The swirls of colour indicate that the brush was applied with some force and disturbed the wet paint beneath it, using a dynamic brushstroke.

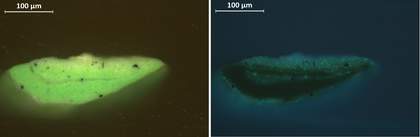

Fig.21

Detail of light green beads

Photo © Tate

Fig.22

Micrograph of light green bead with grey paint from outline of hand

Photo © Tate

Fig.23

Cross-section showing paint from the top green bead in visible light (vis) and ultraviolet light (uv)

Photo © Tate

Image: Fotini Koussiaki

The lighter green beads were also applied with two brushstrokes, a flat circular stroke and then a textured impasto stroke on top (figs.21–22). They contain viridian and lead white, a different pigment mixture, to portray a different light falling on them. The cross-sections reveal a zinc white highlight as the uppermost layer (fig.23).

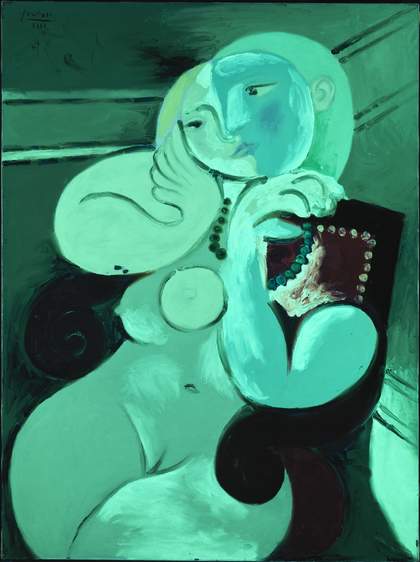

Fig.24

Nude Woman in a Red Armchair 1932 under ultraviolet (UV) light

Photo © Tate

Picasso used both zinc and lead whites, while barium sulphate has also been identified, mostly mixed with coloured pigments. The ultraviolet image renders the highlights of pure zinc white as a bright greenish white, whereas the areas with predominantly lead white appear more dull (fig.24). Picasso was a master of his materials, and he used different white pigments strategically to achieve the desired effects. Zinc white is a very pure, bright white but it is also capable of holding impasto shapes in the brushstrokes, making it ideal for highlights. Unfortunately, it is also quite brittle when applied thickly, and cracks have appeared in some of these areas, for example in the wet-in-wet swirl of white on the red chair and in areas of the face.

There is a restlessness to the paint in this work, and there are no continuous lines. The straight lines in the background are not straight brushstrokes, but were broken into smaller parts that picked up the wet colour beneath and mixed them during the act of painting. The brushstrokes were applied rapidly and with confidence in both directions, meeting but not overlapping.

Fig.25

Detail of breast

Photo © Tate

Fig.26

Detail of upper-left corner

Photo © Tate

The circular outline of the breast was fashioned by a brush bearing several colours (fig.25), which were mixed on the canvas and again painted in opposing directions, almost but not quite meeting at the top, picking up the wet colour beneath. The background to the left of the head seems to have been used to wipe excess colour from the brush in random strokes. The black and grey in this area were painted fast and furiously (fig.26). One of the paler lines was wiped to thin the paint, possibly with a rag or a finger, rather than adding more white.

Fig.27

Detail of nipple of proper right breast

Photo © Tate

Fig.28

Detail of proper left breast

Photo © Tate

The nipples were rendered with very little paint, and like the features of the face, were created by the absence of paint. The proper left breast was painted with relatively thick white paint, but the nipple has a circle of grey underpainting placed directly on the exposed ground around a swirl of impasto in the middle (fig.27). The proper right breast in profile was thickly outlined with black impasto but the nipple itself is virtually unpainted ground with a final brushstroke of white, which leaves a trace on the black impasto below it (fig.28). The nipple itself has a slightly smudged appearance which may be the result of the artist removing paint before applying the final flourish.

Fig.29

Detail of signature and date in upper-left corner

Photo © Tate

The signature at the top left of the painting was painted with great care to give a two-tone effect. Picasso signed the painting with a pale grey paint and then reinforced the letters with a slightly shimmering darker grey paint, which looks almost like graphite in fluid form (fig.29). The date was painted in a different colour and it is interesting to note that the fluid paint goes over an area of impasto which had dried into solid peaks before the date was applied. This would imply that the date and possibly the signature too were later additions, because the brushstrokes of the signature do not seem to disturb the paint underneath, but sit on top of solid ridges of paint.

Picasso is known to have signed paintings sometime after they were completed, when they left his studio to be sold.16 It is possible that this is the case with this painting.

Conclusion

‘The body of work one creates is a form of diary’, Picasso told the art critic Tériade in 1932.17 In a study of Girl Before a Mirror, painted a month before Nude Woman in a Red Armchair, the art historian Anne Umland remarked that Picasso’s words ‘invite us to think about the painting as a visually extravagant journal entry that allows us to peer into his art and life at a particular time and place’.18 Given the contemporaneity of Girl Before a Mirror and Nude Woman in a Red Armchair, the same could well be said about the Tate painting.

In 1932 Picasso had reached the age of fifty, had his first retrospective at the Galeries Georges Petit in Paris from 16 June to 30 July, and had the first volumes of his catalogue raisonné published by the editor Christian Zervos. He had recently acquired his new Château de Boisgeloup in Normandy, where images of him playing with his son, his wife looking on adoringly, were captured on film.19 The very public face of Picasso is one of a successful artist and family man. However, in the words of Tate curator Nancy Ireson, ‘it was clear that a new presence had come into his life. His latest works were dominated by the recognizable features of Marie-Thérèse. Here … the tangible artwork hinted at a secret – wonderful yet challenging – human situation’.20 It is possible that Picasso’s confidence and detachment reached the point where he wanted to reveal his secret lover to the world and free himself from the restraints of married life and social success. The date of 27 July painted on the stretcher bar of Nude Woman in a Red Armchair marks one of the final days of his retrospective in Paris and perhaps records the freedom he was enjoying in Boisgeloup like one would in a diary.

Nude Woman in a Red Armchair is an intimate portrait of Picasso’s lover and muse, but there is also something intimate about seeing the hand of the artist in the immediacy of the technique and handling of paint in this work. The paint is in excellent condition and the traces of the brush are sharp and distinct in the impasto. It is fresh and bright and untainted by age. There is an energy in the brushwork and a tenderness in the touches where the paint is scraped away. It is not known whether Marie-Thérèse Walter posed live for the images Picasso made of her, but one gets the impression that he had memorised and idealised her form, rendering her body in sensual shapes, textures and colours. There is no doubt that Picasso was fired by passion for his young muse and was rejoicing in her body. Although technical examination of the work alone cannot determine whether the work was painted in its entirety on 27 July 1932, the materials and techniques observed would suggest that it is eminently possible.