Pioneering educator and influential artist William Johnstone (1897–1981) has been significantly overlooked in histories of British modernism. Yet his role as the progressive principal of Camberwell School of Arts and Crafts (1938–46) and the Central School of Arts and Crafts (1947–60), both in London, helped shape the work and careers of artists such as Richard Hamilton (1922–2011), Victor Pasmore (1909–1998), Nigel Henderson (1917–1985), Alan Davie (1920–2014) and Eduardo Paolozzi (1924–2005). Looking to the activities of the Bauhaus, Johnstone was instrumental in the development of basic design training in British art schools, while his reach was international: having trained in Paris and travelled in Europe and America, he shared his expertise with art schools in Israel, Sweden and beyond.1

Throughout his career in art education Johnstone continued to practice as an artist and solo exhibitions at London galleries such as Gimpel Fils (1949), Lefèvre Gallery (1953 and 1958) and the Reid Gallery (1960 and 1964), as well as at the Stone Gallery (1961 and 1963) and Décor Gallery (1969), both in Newcastle upon Tyne, indicate his status as an accomplished painter in his own right. This recognition was further underlined late in his life by the large retrospective held at the Hayward Gallery, London, from 11 February to 29 March 1981.2 Since his death that same year, however, a career that spanned over five decades seems to have been largely forgotten outside of Scotland. Small exhibitions such as William Johnstone: Marchlands at the Scottish Gallery in Edinburgh and His Land at Hawick Museum in the Scottish Borders, both in 2012, have gone some way towards marking Johnstone’s position as a distinctly Scottish painter.3 Furthermore, his inclusion in thematic exhibitions in Edinburgh in 2015 and 2016 – Jagged Generation: William Gear’s Contemporaries and Influences and The Scottish Endarkenment: Art and Unreason 1945 to the Present – acts to contextualise his work among that of his closest Scottish peers such as Gear, Wilhelmina Barns-Graham, Robert Colquhoun and Robert MacBryde.4 Yet to claim Johnstone’s painting as something essentially Scottish is to take a limited view and while existing literature on Johnstone acknowledges something of the importance of his early European and American travels for his painting, there is no thorough exposition of that context. This article seeks, for the first time, to question properly the Scottishness of Johnstone’s work, particularly his landscape painting.

Scottishness

In Modern Scottish Painting (1943), commonly considered a manifesto for Scottish art, the painter J.D. Fergusson was clear in his understanding of what it meant for painting to be given the label ‘modern Scottish’:

It must be painting produced by Scotsmen or Scotswomen, not necessarily in Scotland or of Scotland. I mean of Scottish subjects; but it must have the essentials of the Scottish character, and not merely the Scottish character at this moment or of recent years, but something that we feel is and has been inherent in the Scots character throughout history. Something that ‘time but th’impression deeper makes’ would be a heartening feeling, and we would like something that is as true as the geological fault that divides Scotland, or the road to the Isles which is the natural track for both pilgrims and dealers in ponies. Can we find it? Again, perhaps not absolutely, but nearly enough to let us get on with the job. A working meaning of what we call Scotch or Scottish, that brings us to art and nationality.5

Fergusson’s idea of modern Scottish painting that displays something inherent in the Scottish character may have been pertinent in its time, particularly when we consider the publication, also in 1943, of the autobiography of Hugh MacDiarmid, Lucky Poet: A Self-Study in Literature and Political Ideas, and a volume of modern Gaelic poetry by Sorley MacLean entitled Dàin di Emhir. As painter Alexander Moffat and poet Alan Riach observe, the three publications are all artists’ manifestos of sorts, and

Taken together, these three key books signal the co-ordinate points by which a new Scotland was to be created, and Fergusson, MacDiarmid and MacLean might be seen together as artists whose shared vision of what Scotland could be has inspired the nation’s cultural and political regeneration, from the dark times in the middle of the Second World War, to the early decades of the 21st century.6

As Moffat and Riach suggest, the publication of these three books in 1943 was a significant moment for Scotland’s cultural and political regeneration. Perhaps more important for my thinking on Johnstone’s painting is the close relationship that existed between MacDiarmid, Johnstone and the Scottish composer Francis George Scott, all of whom were key protagonists in the new Scottish Renaissance. In the 1920s MacDiarmid proclaimed a Scottish Renaissance that was reactionary and revolutionary in character. Its purpose was to renegotiate Scotland’s past and develop open and innovative cultural forms for the nation’s future, and Scott and Johnstone were part of this too.7 Regardless of the outward-looking aims of the movement, loosely termed, MacDiarmid and Scott respectively produced writing and music that was recognisably Scottish in character. Johnstone’s painting, however, revealed an internationalism that lent it a plurality – a richer context that did not deny its Scottish roots, but rather augmented them. The ideas here are more aligned with that of art historian Craig Richardson, who claimed that: ‘Scotland’s internationally received cultural identity is better understood as a form of fragments or a palimpsest, a federation of geographic regions with varied landscapes, cultures and political priorities, and languages. I promote an inclusive Scottish art which cannot simply be defined by birth or place of residence or any other simple census measure.’8 Richardson continues: ‘over-determination is an anathema to Scottish artists but the situation is complex and the best artistic and critical responses to the demands of affiliation and incorporation have been sophisticated.’9 Almost forty years earlier John (‘Jack’) Knox had already complicated ideas of Scottishness. Framing his selection of work for the inaugural exhibition at Fruitmarket Gallery, Edinburgh, in 1975, Knox recognised that:

Besides their age, the other common factor I mentioned is that they are all Scottish. But what does this mean in the context of their work? Should we infer from this that underlying their very different approaches there is something distinctive which gives their work a particular Scottish character? There may well be, but we should not come to their work encumbered with preconceived notions of ‘certain Scottish characteristics’.10

Knox began his introductory catalogue essay by eschewing the idea of groups or categories all together, suggesting that:

when it comes down to it, art is a very personal thing – it is one man’s idea of what life is all about, and everything he makes is his metaphor of the process of living. Behind the surface appearance of what he does lies his whole attitude to life, and he will develop his own artistic language when his ideas and feelings and the means he devises of expressing them are perfectly integrated.11

Johnstone’s position as an artist who trained, taught and exhibited in Europe and America, as well as his status as the principal, successively, of two major London art schools, already mark his painting as something other than straightforwardly Scottish. It has to be understood in a wider context, one that includes his formative travels to America. Johnstone may have followed a tradition of Scottish painting that included that of his teachers Tom Scott and Henry Lintott, but he did so on his own terms. To pick up on Knox’s distinction, it would be wrong to suggest any traditional characteristics that make Johnstone’s paintings Scottish in, say, Fergusson’s sense of the term. So while this article does not refute Johnstone’s identity as a Scottish painter, it complicates that identity, accounting for wider contexts and suggesting a relationship with the Scottish landscape that sent him elsewhere, only later to return.

A traumatic topography

What grounds might there be to indicate that Johnstone’s relationship with the landscape was a troubled one? My suggestion here is that Johnstone’s landscape paintings are spatial representations of different times and places, pressed into and upon one another. There is nothing clear cut about his paintings, which, if anything, present the viewer with a psychical landscape rather than a purely physical one. Furthermore, the fusion inherent in these images is perhaps indicative of Johnstone’s ambiguous relationship with the land.

Fig.1

William Johnstone at Greenhead Farm in 1912

Photographer unknown

Hawick Museum, Hawick

Johnstone held a deep fondness for the land that had supported his family during his childhood (fig.1). Yet there is also a sense of disappointment at a homeland that could not offer him a living. Leaving and returning, as if to the scene of some traumatic event, we might ask if he was searching for reparation, or at least a clearer understanding of that context, in his repeated painting of the land.12 As sociologist Kai Erikson suggests:

trauma has both centripetal and centrifugal tendencies. It draws one away from the centre of group space while at the same time drawing one back. The human chemistry at work here is an odd one, but it has been noted many times before: estrangement becomes the basis for communality, as if persons without homes or citizenship or any other niche in the larger order of things were invited to gather in a quarter set aside for the disenfranchised, a ghetto for the unattached.13

Fig.2

William Johnstone

Golgotha 1927–8 and c.1948

1381 x 2416 mm

Tate T03292

Fig.3

William Johnstone

A Point in Time 1929/1937

1372 x 2438 mm

Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh

A traumatic topography for Johnstone’s landscape painting makes more sense when we consider monumental works such as Golgotha 1927–8 and c.1948 (fig.2) and A Point in Time 1929/1937 (fig.3). Art writer and critic Paul Overy called the latter ‘a masterpiece of surrealist-abstraction unrivalled in scale and ambition in British painting of the 1930s’.14 The sheer scale of these works is overwhelming. As Johnstone recalled in 1973, A Point in Time is an anti-war painting that is perhaps, as mentioned, more a psychical landscape than a physical one.15 His commentary on the painting supports this idea since, as he claims, its meaning and message emerged only upon its completion, a wartime experience unconsciously wrought upon the canvas.16

Despite the brevity of Johnstone’s period of national service in 1918–19, the lack of combative duties and his subsequent posting to his own father’s farm, the experience affected him deeply.17 In his autobiography Johnstone recalls the darkness of war, still clear in his mind in 1980, and describes a scene full of dread from 1918:

By that time the last dregs of humanity seemed to have been collected to be food for rats. Old soldiers who had returned from the front were so disillusioned and debased by Passchendale and the Somme battles that they were really depraved men, and their influence permeated the barracks. The point of exhaustion had been reached when nobody would lift a hand. They were dead men and the Germans could have run them over; they would have given up without fighting. Those men were simply worn out by the effort; there was no long-long-way-to-Tipperary about it, they walked with dreary gloom on our route marches. You felt you could never survive this terrible influence without sinking into some fearful slough of degeneracy.18

In Johnstone’s case, therefore, his brief conscription was served initially under a shadow of war that brought with it the genuine possibility of combat and the trauma inherent to that context, despite it being unrealised. As psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud explained in the second of three addenda to his essay ‘Inhibitions, Symptoms and Anxiety’ (1926):

A danger-situation is a recognized, remembered, expected situation of helplessness. Anxiety is the original reaction to helplessness in the trauma and is reproduced later on in the danger-situation as a signal for help. The ego, which experienced the trauma passively, now repeats it actively in a weakened version, in the hope of being able itself to direct its course.19

Fortunately for Johnstone he was transferred to the Labour Corps and in November 1918 posted to Greenhead farm, his father’s farm, for agricultural service. He arrived home in Selkirk on the morning of 11 November 1918, the day that the Armistice was to be declared at 11 am. He later recalled surveying the landscape upon his return:

It was the scene where I had played all my parts since childhood but, alas, it was no longer a part of me. We had separated and all that had seemed so natural, so at one, was no more, my life could never be the same again. That morning the sun shone in all its glory as if it had never shone before and there was a curious unnatural stillness, as if all life had become static. I heard the town clock strike eleven.20

The poetic nature of Johnstone’s recollections, written more than sixty years later, may reflect a nostalgic remembering or simply a florid imagination. Yet the simplicity of the language used seems to intensify the sense of loss he so clearly experienced. There is profound sorrow for his relationship with the land, a relationship since transformed beyond recognition then relinquished, for a short time at least. The striking clock marks an ending and a beginning, a past that is now lost and a future that is yet to come.

An international artist

Johnstone’s credentials as an artist and writer of international standing were established at the outset of his artistic career. Entering Edinburgh College of Art in 1919 on an ex-serviceman’s grant, he took advice from Tom Scott, with whom he had previously studied on an informal basis, and went to Holland, spending 1921–2 studying the work of Rembrandt van Rijn (1606–69) and Frans Hals (1580–1666). In 1925 he was awarded a Carnegie Travelling Scholarship by the Royal Scottish Academy, settling in Paris in the autumn of 1925 for a stay that would last two years. He attended drawing classes at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière and the Académie Colorrossi and trained in the studio of André Lhote. In doing so he was part of the common trend in the early twentieth century for Scottish artists to study in Paris. In the spring of 1926 he travelled on to Spain, Italy and North Africa with Max Bernd-Cohen, an American lawyer-turned-artist who was to become a lifelong friend. The following year Johnstone married Flora MacDonald, an American studying sculpture in Paris. His circle of acquaintances in Paris at that time included the artists Alberto Giacometti, Fernand Léger, Amédée Ozenfant and Germaine Richier, and the collectors Leo and Gertrude Stein.

After returning to the Scottish Borders, Johnstone and his new wife were unable to find work and left for America in 1928 in search of employment. With the Wall Street Crash of 1929, however, Johnstone found himself in a financially precarious position once again. Leaving America, a land that had appeared so promising, he returned, briefly, to Scotland before heading to London and the start of a teaching career that would last more than thirty years.

Fig.4

William and Mary Johnstone outside Frank Lloyd Wright’s house, Taliesin, 1948

Photographer unknown

Hawick Museum, Hawick

Subsequent visits to America with his second wife Mary in 1948, 1949 and 1950 were much shorter and focused on discrete commitments on Johnstone’s part. In 1948 he conducted a survey for London County Council on the training of American students in industrial design, during which he met with founder of the Bauhaus Walter Gropius, among others.21 In 1949 Johnstone undertook teaching duties as Fulbright Lecturer and Director of the Colorado Springs Fine Art Centre Summer School, a role he took up again in 1950. He also lectured at the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation in Taliesin, Wisconsin, in 1949 and 1950 (fig.4).22 The turn of the 1950s saw his first retrospective exhibition at the Colorado Springs Fine Art Centre, covering work from the period 1925 to 1950.

Johnstone’s international outlook was grounded in these early European and transatlantic experiences.23 It first emerged in his writing in Creative Art in England (1936), later revised and republished as Creative Art in Britain (1950).24 Here Johnstone valued British art as part of an expansive global context and proposed a working definition of British art:

By British art I do not mean art which refuses to accept the contribution of France, Italy, Russia or China to the world, but rather an art tradition which encourages the British artist to contribute at least as much as receives. He accepts the valuable contribution of France in a creative and assimilative way, rather than a merely imitative spirit. In this way painters abroad will similarly feel able to accept the British contribution to the art of the modern world.25

What he advocated was an international dialogue that British art and artists might learn from and contribute to in equal measure. This was distinct from other views articulated in England at this time. In his 1955 Reith Lectures, for instance, émigré art historian Nikolaus Pevsner held up the English tradition as an exemplar, suggesting ‘the English tradition … has much to teach the Continent and America, and foreigners’.26 Pevsner talks of English rather than British art, but the sentiment remains and seems at odds with Johnstone’s internationalism.

Johnstone in America

When Johnstone first lived and worked in America, he encountered a very different landscape to that he had grown up with in the Scottish Borders. In 1928 he lived in Los Gatos and then San Francisco. He taught life painting at the California School of Arts and Crafts for a term under Xavier Martinez and saw work by artists of the Mexican School. The following year he moved to Carmel, an artists’ colony in California, and established a painting school. Johnstone’s recollection was that Mabel Dodge Luhan, the automobile heiress and arts patron, also lived in Carmel at this time and played host to artists and writers. John Steinbeck was among them and his later book Tortilla Flat (1935) features the town.27 John Catlin, an acquaintance of Johnstone’s in Carmel, introduced him to Matthew Murphy, a local private collector of Indian sand paintings and rugs.28 Johnstone was fascinated by the collection, which he visited repeatedly, turning his thoughts towards his own Celtic heritage and the possibilities therein for developing his painting. He recalled:

When I studied those Indian paintings, so simple, with such depths of intensity in the abstract patterns, I was reminded of the old Scottish and Pictish carved stones which we had studied in Edinburgh. I remembered the great Celtic and Saxon carvings; I remembered the Book of Kells and the Lindisfarne Gospels; I remembered the Bewcastle and Ruthwell crosses, the Burghead Bull, St Cuthbert’s coffin at Durham. I realized that, in this early Northern art, there was something for me. I decided to return home to study this earlier heritage again, to see whether or not it was important for me as an artist. I thought I had found the clue for which I had been searching.29

In this sense, the visual field that Johnstone encountered in America acted obliquely, returning him to his Celtic roots and a heritage that he discovered afresh as a valuable point of reference for his own artistic development.

Johnstone’s visual interest in his visits to America of the 1940s nonetheless seemed more focused on the surrounding landscape than on local artistic traditions, and he took a series of more than forty photographs of the towns and landscapes through which he travelled. In these Johnstone captured scenes of the Taos Pueblo, the Rocky Mountains and the Colorado mining towns, and the careful composition of these photographs indicates that the scenes they captured may have been significant to him, and to his painting. My suggestion here is that a dialogical relationship between Johnstone’s subsequent landscape paintings and the American landscape he encountered during these earlier visits was mediated by these small photographic images. The photographs, and Johnstone’s notes scribbled on their verso, gesture to his perspicacity, an acuity of vision and observation that is, perhaps, nothing more than might be expected of a painter. Still, my argument for a more specific connection of these photographs to his painting is supported by the precise nature of three individual examples (figs.5, 7 and 8).

Fig.5

William Johnstone

Large Pueblo, Taos, New Mexico 1949–50

Photograph

Hawick Museum, Hawick

Fig.6

William Johnstone

Pink Landscape 1954

Oil on canvas

Bangor University, Bangor

In his photographs of the Taos Pueblo such as Large Pueblo, Taos, New Mexico (fig.5) Johnstone particularly notes the adobe plaster of the buildings, an organic material that renders a warm, chalky finish. Unlike the cold, locally occurring granite, sandstone and siltstone often used in buildings in the Scottish Borders, adobe plaster is not hewn from the landscape itself, but made by combining naturally occurring materials: earth is mixed with water and organic matter such as animal dung or straw. The earth used is a combination of sand, clay and silt, lending the plaster a freer finish than many other building materials. This kind of construction was alien to the dwellings and landscape of Johnstone’s Scottish homeland, where stone-built houses stand solidly among the hills, designed to withstand the wind and rain of harsh Scottish winters. Yet in works such as Pink Landscape of 1954 (fig.6) Johnstone presents a light, fluid wash of paint, exhibiting a warmth and opacity that seems at odds with the Scottish landscape. Instead, this landscape evokes the enfolding warmth of the pueblo and its peoples, suggesting its continuing importance in Johnstone’s work.

Fig.7

William Johnstone

The Rockies 1949–50

Photograph

Hawick Museum, Hawick

Fig.8

William Johnstone

Colorado Mining Town 1949–50

Photograph

Hawick Museum, Hawick

Fig.9

William Johnstone

Composition 1959

Oil on canvas

Hunterian Art Gallery, University of Glasgow, Glasgow

When it came to landscape painting, the ruggedness of the Rockies (fig.7) and the scarred landscapes of the Colorado mining towns (fig.8) were another reference point on Johnstone’s artistic compass. In Composition of 1959 (fig.9), for instance, areas of black paint cut across the canvas, scarring the picture field, much as the activities of the mining towns scarred the Colorado landscape. Indeed, the harsh landscape of the Rockies and of the Scottish Borders were both difficult environments in which to exist, even if their climatic conditions sat at opposite extremes. In Composition Johnstone perhaps juxtaposed the dank greens of Scotland with the red-hot crimson of Colorado. In these ways, elements of American imagery emerge in Johnstone’s paintings, even where their primary origin is the landscape of the Scottish Borders.

Johnstone’s correspondence with the American Max Bernd-Cohen is helpful in better understanding this transatlantic artistic dialogue.30 The two met in Paris in 1926 and exchanged visits and letters throughout their lives. It is perhaps inevitable that the correspondence between them should centre on recent developments in art. In 1964, when Berndt-Cohen was living and working in Saratosa, Florida, the local press reported on new international exchanges between the artist and his old friend Johnstone, and a year later, in 1965, another newspaper article marked his return. Johnstone had helped Bernd-Cohen secure the job of establishing a General Studies department at Carlisle Art College in Cumbria in the north of England, just across the border from Johnstone’s home in the Scottish Borders. Bernd-Cohen planned a syllabus for a three-year course including studies in art history, sociology, geomorphology, music, literature, philosophy and optics.31 What is evident throughout their personal correspondence is the concern of both artists with the tension between individuality and influence. In a letter dated 22 May 1957 Bernd-Cohen pointed to two traits, potentially at odds with one another: on the one hand, the sensitivity of the artist, and on the other the strength of character required in assimilating influences while firmly establishing a unique style, regardless of contemporary trends or fashions.32 Despite having worked in an abstract expressionist fashion, even before the paintings of American artist Jackson Pollock (1912–1956) emerged in major exhibitions in Britain, Johnstone was an artist who clearly followed his own path and departed from the more familiar narratives of abstraction and British art in the mid-twentieth century.33

Abstract painting

Johnstone was largely interested in abstracting from nature, claiming in 1980 ‘I am part of nature and nature is part of me’.34 At the same time, he was invested in intuitive modes of working. His interest in child art informed his approach to both teaching and painting, concerned as he was with a freeing up of inhibitions. The art of children and so-called primitive artists provided Johnstone with a point of reference for his own work, not necessarily visually, in terms of what sorts of images to produce, but procedurally, in terms of how to approach the act of painting. He had already published his book Child Art to Man Art (1941) when the American Jean Lipman published American Primitive Painting (1942), a book that Johnstone then bought. Lipman suggested that in trying to capture nature, the primitive painter engaged a spontaneous psychical function to reproduce internal, mental images, rather than external reality. Her suggestion was that ‘[t]he style of the typical American Primitive is at every point based upon an essentially non-optical vision. It is a style depending upon what the artist knew rather than what he saw, and so the facts of physical reality were largely sifted through the mind and personality of the painter.’35 It is not difficult to imagine that Lipman’s words would have struck a chord with Johnstone as he developed his own ideas on the subject and took his painting forward into the 1950s and beyond.

Fig.10

Anton Ehrenzweig teaching in the textiles studio, Central School of Arts and Crafts, London, c.1951

Photographer unknown

Tate Archive TGA 201010

These sorts of ideas also resonated with those of Johnstone’s friend and colleague, the art theorist Anton Ehrenzweig, who worked at the Central School of Arts and Crafts during Johnstone’s tenure as its principal, and whose own writing was particularly revealing of Johnstone’s painting and working methods (fig.10).36 In 1959 Ehrenzweig identified three stylistic phases in Johnstone’s painting: firstly, what he called Johnstone’s surrealist phase of the 1930s, then his cubist phase of the 1940s and finally his calligraphic or tachist phase of the 1950s. Ehrenzweig noted:

We observe an increasing abstraction and simplification, and the emergence of the spare semi-abstract motifs that serve Johnstone today to build his richly textured landscapes … Landscape motifs first appear in near-naturalistic form, as in the Colorado Springs drawings … Their realism and formal unity is deceptive; on closer scrutiny they prove a conglomeration of disjointed motifs, thrown together like studies in a sketch-book.37

What Ehrenzweig identified in Johnstone’s work is evidence of an organic, evolutionary process at work such that apparently disjointed motifs come together with a unity of form. This was well aligned with Ehrenzweig’s idea of art’s ‘hidden order’, later to appear in his seminal book The Hidden Order of Art (1967).38

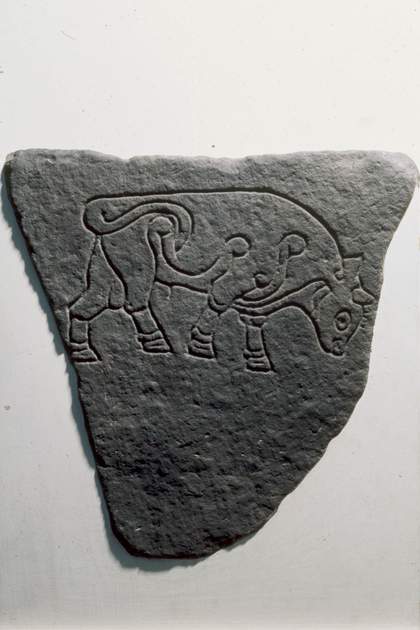

Fig.11

The Burghead Bull, 7th–8th century AD

Pictish stone carving

British Museum, London

Ehrenzweig recognised many of these same motifs in Johnstone’s later drawings, which became increasingly integral to Johnstone’s more painterly work. This linear, more calligraphic aspect to his painting may be related to two different cultural forces. Firstly, the Celtic art of his own Scottish heritage, which he had studied as a young man in Edinburgh when he visited the Queen Street Museum to study Celtic and Pictish work in the late 1920s and early 1930s after his return from America. In the same vein, he also acknowledged the debt he owed to G. Baldwin Brown, his teacher at Edinburgh College of Art, and Brown’s insights into Saxon and Celtic art. The cover of Johnstone’s books Creative Art in England (1936) and Creative Art in Britain (1950) bear the imprint of that heritage in the form of the Pictish carving known as the Burghead bull (fig.11). Here, the flourish of organic line and form, the apparent rests and shifts of bovine breath and muscle seen in the bull, are just as expansive in Johnstone’s calligraphic exploration of highlands and lowlands in works such as Pink Landscape 1954 (fig.6).

We might pause to wonder where works such as these might sit in relation to a wider movement towards painterly abstraction in America and in Britain during the 1940s and 1950s. It is difficult to say precisely which paintings of this kind by American artists Johnstone may have encountered when he travelled there in the 1940s. His autobiography and the contents of his library suggest that he was more interested in Native American art and the work of the New Mexico School at that time. At the California School of Arts and Crafts he taught life painting for a term in 1928 under Xavier Martinez, whose circle of friends included the painters Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco and David Alfaro Siqueiros.39 Therefore, Johnstone was exposed to the work of the Mexican muralists long before they became an important point of reference for American abstract expressionist painters such as Jackson Pollock.40 Historian Douglas Hall speculated in his book William Johnstone (1980) that Johnstone’s first wife, Flora, would have kept him abreast of developments in contemporary American art, and that it is possible he saw work by modernist painters Arthur Dove and Georgia O’Keeffe at the Stieglitz galleries as he passed through New York, although Johnstone, when asked by Hall, did not recall this.41 Still, he would have had ample opportunity to see exhibitions of work by American artists during his years living and working in London (1931–60). As far as painterly abstraction in Britain is concerned, there are visual resonances between Johnstone’s work and that of some of the St Ives artists, such as Peter Lanyon and Wilhelmina Barns-Graham. This makes sense when we remember that Johnstone and Barns-Graham shared friendship groups and that they both returned to Scotland in 1960, she to St Andrews and he to the Scottish Borders.

Johnstone’s Celtic roots, however, were not the only point of reference for his abstracted landscapes. As I have already suggested in this article, and as Ehrenzweig noted in 1959, Johnstone’s renewed contact with America in 1949 and 1950 seems to have hastened the development of a freer, semi-abstract painting style.42 This is evidenced not only in the places and people he encountered on his travels, but also in his reading matter on the local landscape and culture. One such publication was Stampede to Timberline: The Ghost Towns and Mining Camps of Colorado (1949) by American artist Muriel Sibell Wolle. The book presents a record of the Colorado mining towns before they disappeared or were poorly restored, and is illustrated with almost two hundred of Wolle’s own drawings. From sketches of Beartown, Summitville and Ohio City, to others of Mosquito Pass, North Creede and Cripple Creek, Wolle recorded the shops, schools, hotels, churches and courthouses of communities long since lost. According to Wolle, each mining camp ‘flourished until the ore played out. Then the miners left and the camp became dormant or deserted.’43 What attracted Johnstone to these images is difficult to say. It may be that he recognised parallels between the desolate ghost towns and scarred landscapes of Colorado and the remote hills and valleys of his Scottish homeland. In any event, the influence of the American landscape seems to re-emerge in his later drawings and paintings.

Two years earlier, in the state of Colorado, the Work Projects Administration had compiled an illustrated issue of the American Guide Series titled Ghost Towns of Colorado (1947), which was also among the publications collected in Johnstone’s library. A small booklet containing almost sixty illustrations, it would have struck a chord with Johnstone. While the towns, plains and landscapes of Denver, Leadville and Blackhawk in Colorado were hardly reminiscent of the towns, hills and valleys of Selkirk, Hawick and Ettrick in the Scottish Borders, they nonetheless displayed certain resonant qualities. Both locations were examples of particularly remote and harsh environments. The tough conditions experienced by the mining communities of Colorado may have been a measure for Johnstone, a way of calibrating his own experience of the difficulties of farming in rural Scotland, working the land or following the shepherds on the drove.44

Both, I suggest, appear remodelled in paintings by Johnstone such as Ploughed Field 1963 (Hawick Museum, Hawick) and Composition 1959 (fig.9). Here sun-scorched Colorado meets wind-scoured Scotland in the mind of the maverick painter. His enduring commitment to the natural landscape, and nature more broadly, and to the role of the human unconscious in creativity, alongside a detailed and nuanced understanding of the material qualities of paint and canvas, mean that his paintings are much more than simply abstract line and shape on canvas.45 Here we can experience an evocation of mental imagery and a psychical landscape. The dank, dreich-sodden greens of rain-soaked Scottish hills and valleys and the vivid, fiery oranges of arid, sun-scorched Colorado or the New Mexico desert come together, but not to represent those times and places in Johnstone’s life. Rather, they evoke how his unconscious processes bring these past episodes to the fore, reconfiguring them in the present, and moulding and enmeshing them with aspects of the view beyond his window and his immediate experience of nature. As Johnstone later reflected:

I am part of nature and nature is part of me. When the wind blows cold, I feel it. When the sun comes out, I feel it. When I put the paint on there, I feel it but I put the paint on it. It’s a unity, it’s unification. It’s an absence up to a certain extent of the material world.46

This is clarification, if it were needed, of the importance for Johnstone of painting as experience rather than representation. While one cannot represent the feeling of wind or sun on the painter’s skin, one can evoke something of that experience in abstract terms. Johnstone’s painting might precipitate the experience of summer sun in Selkirk or of driving rain on the Ettrick Hills. Still, he is clear that the work is not in any respect representational. In this way, the landscape abstracted from nature is also the painter’s inner vision extracted from the subconscious and deposited upon the canvas. Johnstone’s insistence on painting as a craft, on the essential skills of the painter, and on a need for a fundamental understanding of the painter’s tools and materials might seem to contradict this kind of intuitive abstract practice. Yet Johnstone might have said that if the artist is fully prepared, is equipped with the right tools and the relevant skills, then he or she is ready to grasp what Johnstone called that ‘point in time’, a moment that offered the possibility of creating something unique.

As we have seen, throughout his career Johnstone developed his own painting style from diverse points of reference on both sides of the Atlantic and elsewhere. Above all, he looked to the landscape and trusted his own intuitive modes of working to produce results that satisfied him. As Ehrenzweig recognised:

Johnstone’s work, varying as it does from utter simplicity to intricate complex sequences of colour and tone values, is that of a stubborn individualist, very much of his time, but never wholly allied to any particularly mass movement or fashion. He must, through his personal experience with paint, work out his own destiny.47

Clear in his identity as a Scot, Johnstone nonetheless looked far beyond the borders of his homeland to produce paintings that owed a great deal to his experience of the American cultural and natural landscape. He returned to the landscape of the Scottish Borders with memories and traces of another, American landscape that leaked out into his paintings. Despite titles, tones or sentiments that often gesture directly or obliquely to the Scottish Borders region, these paintings also carry within them traces of Carmel and Colorado. These are not Scottish paintings, but contributions to international modernism.