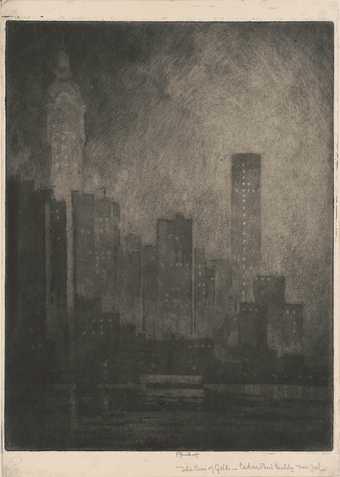

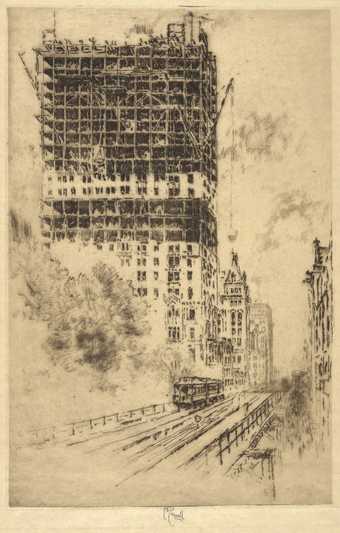

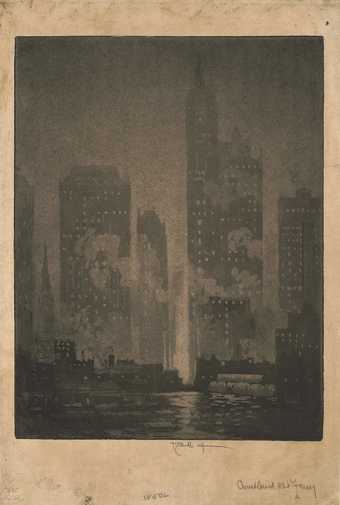

Fig.1

Joseph Pennell

The Cross of Gold, Cedar Street Building 1908

Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

During the first years of the twentieth century New York City’s extraordinary skyscrapers became powerful symbols of America’s emergence as an economic and industrial superpower. In the pantheon of artistic depictions of machine age New York, the best-known today were made in the aftermath of the First World War, notably by American artists such as Charles Sheeler and Joseph Stella. However, these figures were building upon an architectural iconography established by precursors active in the century’s first decade. During those years, little-studied American artist Joseph Pennell played a key role, I shall argue, in popularising iconic visions of the metropolis and in establishing a new aesthetic vocabulary to describe it. For example, Pennell’s 1908 sandpaper mezzotint The Cross of Gold, Cedar Street Building (fig.1) takes on the atmospheric effects of a Whistlerian nocturne such as Nocturne: Blue and Silver, Battersea Reach 1870–5 (fig.2), but emphasises the flat surfaces and hard edges of the city’s skyscrapers. The buildings’ opaque facades limit the scene’s sense of depth while glowing windows, set against the night sky, accentuate the setting’s unique verticality. Such features, which called attention to the city’s distinct physicality compared to European urban centres, would underpin portrayals of New York by artists working in the next decade.

In her important 1973 article ‘The New New York’, cultural historian Wanda Corn discussed the wide range of new perceptions offered by the city, such as the wondrous sight of Broadway glittering at night, the majestic heights of skyscrapers and the Ashcan School’s dynamic and intimate paintings of the city’s streets.1 Corn showed that early interpretations of the city were often indebted to past visual archetypes, like the picturesque or the sublime. However, as New York grew it began to demand a fresh aesthetic, one more in tune with modernist sensibilities, which took advantage of the city’s inherent geometry and new vantage points. Pennell is left out of Corn’s deliberations, and in her later book The Great American Thing: Modern Art and National Identity, 1915–1935 (1999) his role in this narrative is only marginally summarised.2 Anne Cannon Palumbo’s 1982 unpublished PhD thesis, the only extended account of Pennell to date, provides an in-depth discussion of his career, briefly acknowledging that Pennell met the challenge of his new subject matter with increased methodological experimentation, culminating in his 1908 New York works.3 However, even Palumbo primarily emphasises Pennell’s use of picturesque stylistic tropes to depict Manhattan and modern factory cities instead of highlighting his role as innovator. ‘The cathedral’, she states, was ‘simply transformed into the skyscraper … [Pennell’s] achievement was to record the landscape of change. He left to others to discover its distinctive forms.’4

Fig.2

James McNeill Whistler

Nocturne: Blue and Silver, Battersea Reach 1870–5

Oil on canvas

Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

Most significantly, neither Corn nor Palumbo analyse Pennell’s early images of New York through his experience as an expatriate. This is especially surprising given that these pictures were created during periods in which Pennell visited America but lived primarily in Britain. As such, there is fruitful opportunity to produce new historical perspectives on the formation of New York iconographies by looking at Pennell’s development through a lens that emphasises his role as an Anglo-American artist.5 It is striking that American artists who established New York as an artistically viable subject did so after spending significant periods of their careers in Europe. Colin Campbell Cooper, Alvin Langdon Coburn and Pennell all began depicting cityscapes in Europe before returning home and recognising the New World’s drastic contrasts. Therefore, the formation of Pennell’s modern New York was stimulated by a rupture of his European, specifically British, sense of what was pictorially acceptable as far as urban centres were concerned.

This article seeks to demonstrate that Pennell’s first two sets of New York prints, inspired by visits to America in 1904 and 1908, were important liminal depictions that projected romantic views of Manhattan while simultaneously establishing an artistic language for a new machine age. It will also show that Pennell’s struggle to formulate this new aesthetic often led to nationalistic pictures that implicitly posit America’s skyscrapers as symbolic usurpers of British cultural patrimony. Nevertheless, despite his patriotic attitude toward his country of birth, this paper will show that Pennell’s ideologies and stylistic principles stemmed not only from his American predecessors and contemporaries, but also from his British peers. How did Pennell’s experiences living in London and his knowledge of British art affect his depictions of the American metropolis? Ultimately, how might revealing this transnational exchange inflect our reading of Corn’s seminal narrative surrounding the legacy of New York imagery? This study augments Corn’s scholarship by providing a more comprehensive analysis of Pennell’s representations of the city for the first time in this context.

Philadelphia to London

Pennell’s interest in modern industrial subjects was established early on in his career. After taking classes at the Philadelphia School of Industrial Art in the late 1870s he was accepted into the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, where he studied under Thomas Eakins. Around this time Pennell began making drawings and watercolours of the Bethlehem Steel works, just north of his native Philadelphia (fig.3). Less like a product of the industrial revolution, Pennell’s steel mill is more reminiscent of paintings from the Dutch Golden Age of windmills set on quaint canals (see, for example, Jacob van Ruisdael’s The Windmill at Wijk bij Duurstede c.1668–70, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam). The proximity of the factory to water and its elegant steam clouds illustrate Pennell’s earliest use of picturesque tropes to depict large-scale industry. By 1881 several of his drawings, including an image of an oil refinery, had been printed in Scribner’s Magazine, a popular literary periodical that soon became the Century Magazine.6 This commission ignited his career as a graphic artist specialising in architecture, with subsequent commissions from international periodicals allowing his work to be seen widely in both America and Britain.

Fig.3

Joseph Pennell

Bethlehem Steel Works 1881

Watercolour

Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

In 1884 Pennell was commissioned by the Century Magazine to complete a long-term assignment producing drawings of London and Italy, as well as English and French cathedrals. To fulfil this assignment Pennell and his wife, the writer Elizabeth Robins Pennell, took up residence in London and quickly became immersed in the city’s literary and artistic circles.7 Throughout these years the Pennells co-authored books and articles that were often centred on the topic of their European travels and tailored for a readership interested in their exotic destinations.8 In London Pennell was elected a committee member of the International Society of Sculptors, Painters and Gravers and through his growing renown as a graphic artist he obtained many commissions for book illustration.9 He also cultivated friendships with the writers Henry James, H.G. Wells and George Bernard Shaw and the painters John Singer Sargent, and, perhaps most importantly, James McNeill Whistler, who would significantly influence his practice.10

Fig.4

Joseph Pennell

New Oxford Street, London 1893

Etching

National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

Fig.5

James McNeill Whistler

St. James’s Street 1878

Etching

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Fig.6

Joseph Pennell

A Lion Comique, at the Oxford c.1890

Gouache

Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

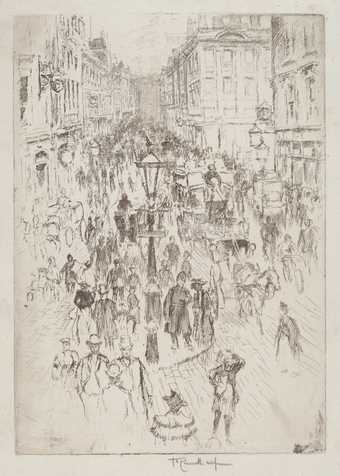

Pennell’s pictures from the 1880s and 1890s depict many urban European subjects in a distinctly Whistlerian style, from Venice’s skyline to London’s winding streets. Pennell’s New Oxford Street, London 1893 (fig.4) presents a detailed treatment of pedestrians and buildings comprised of variegated mark making, seen from an elevated vantage point, similar to Whistler’s St. James’s Street 1878 (fig.5). However, some renderings reveal other surprising influences. Pennell’s A Lion Comique, at the Oxford c.1890 (fig.6) shows a popular character in Victorian London music halls atop the stage at left, with the orchestra pit and elegantly dressed middle-class ladies and gentlemen in the front stalls, while a line of ghostly faces in the cheap seats look on from above. Pennell was obviously aware of Walter Sickert’s famous music hall paintings that depicted class integration in London’s urban nightlife (see, for instance, Music Hall or The P.S. Wings in the O.P. Mirror 1888–9, Musée de la Ville de Rouen, Rouen).11 However, this was only a brief foray for Pennell, who was far more interested in the physical spectacle of cities than their human inhabitants.

Fig.7

Joseph Pennell

St. Paul’s from the River 1894

Sandpaper aquatint

Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven

Pennell’s friendship with Whistler was solidified in Paris in 1893, when the latter requested Pennell’s aid in printing a series of etchings depicting Parisian shop fronts.12 The time spent learning from Whistler appears to have solidified his fascination with cityscape subjects. Immediately following this collaboration, Pennell created five sandpaper aquatints of nocturnes along the River Thames.13 Both in terms of subject matter and surface texture, these prints attempted to adapt Whistler’s London nocturnes made in oil to Pennell’s preferred medium. In the print St. Paul’s from the River (fig.7) Pennell interrupts the horizon with a fishing boat crane and juxtaposes its hard edge against the round dome of St Paul’s Cathedral, barely discernible through an ethereal haze. Similarly, Whistler’s Nocturne: Blue and Silver, Battersea Reach (fig.2) uses the effects of night and water to obscure the pointed silhouettes of fishing boat cranes and smoke stacks, turning modern industrial subjects into something enchanted. Both Pennell and Whistler observed that the London cityscape was undergoing radical changes. Around the city’s old Georgian squares and seedy rookeries newer buildings and large-scale industry were creating picturesque contrasts of old and new.14 In the coming years this juxtaposition would become even more obvious in New York, where contemporary structures eventually usurped the old.

The first New York set, 1904

Pennell’s first trips back to his homeland occurred in 1904 and 1908. Apart from two visits before the turn of the century – once to organise his father’s estate and again to visit the World’s Colombian Exhibition in Chicago – by 1904 Pennell had not spent a significant amount of time in his native country for twenty years.15 The New York he remembered was not the metropolis he encountered upon his arrival in New York Harbor.16 London’s tallest building at that time was Queen Anne’s Mansions on Petty France in Westminster. Built in the 1870s, this was the city’s first set of high-rise flats. Pennell made an etching of the building a year before his arrival in New York, but even a structure of 116 feet comprising ten stories could not prepare him for the scale of Manhattan. In his absence the city had become unrecognisable. The year 1900 saw fifteen buildings completed that exceeded twelve storeys. By the end of 1902 sixty-six buildings with heights varying from nine to twenty-five storeys had been erected.17

Fig.8

Joseph Pennell

The Cliffs 1904

Etching on cream laid paper

Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago

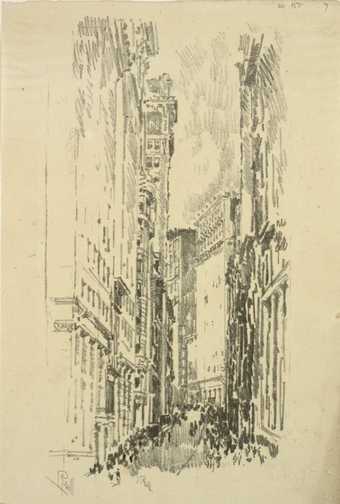

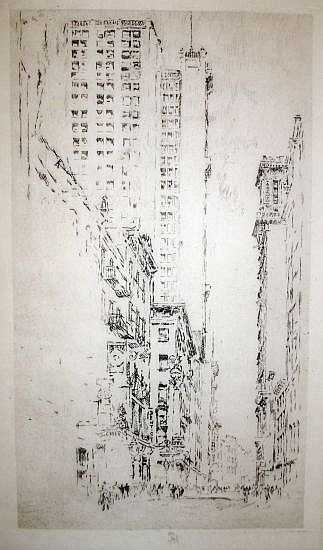

Fig.9

Joseph Pennell

The Cañon, William Street 1904

Lithograph

Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Print Collection, New York Public Library, New York

© Joseph Pennell; The Society of Iconophiles New York MCMV

Many of Pennell’s first pictures of New York drew upon an aesthetic vocabulary of urban representation developed by American impressionist painters. Colin Campbell Cooper, Childe Hassam and Pennell all exploited Lower Broadway for its views of skyscrapers with swarming crowds below. What differentiated Pennell from these contemporary American painters was his enthusiasm for a twentieth-century dynamism that often manifested itself in fantastical exaggeration. The Cliffs (fig.8), for example, shows a cluster of skyscrapers grouped impossibly close, flattening the background, while an El train loops in from the side of the picture, its raised track establishing a dramatic sense of perspective. Pennell’s fantasy city appears to reinvent eighteenth-century Italian capricci representing cities on the Grand Tour, which often placed well-known buildings together in order to give viewers an overall impression of a specific milieu. However, even more than his impressionist contemporaries or eighteenth-century precursors, Pennell showed an interest in bearing witness to the city in flux.

During his 1904 visit Pennell produced over sixty prints and a set of twelve lithographs for the Society of Iconophiles that documented New York’s dramatic metamorphosis.18 Six prints from this series were published in the Century Magazine in March 1905, including images of the Flatiron Building, the Times Building, skyscrapers in various states of construction and the iconic print The Cañon, William Street (fig.9), which formed the article’s frontispiece. In this image the city’s skyscrapers are portrayed as cliff-like facades encroaching upon a teeming river of pedestrians in New York’s financial district. As with many artists attempting to depict Manhattan during this period, the metaphorical presence of nature took on various roles. Terms like ‘canyon’ and ‘cliffs’ in Pennell’s titles reflect comparisons to the American West that were often applied to the cityscape as a way for artists and writers alike to make its unfamiliar and massive environment comprehensible.19 Pennell’s skyscraper ‘canyons’ recall the mid-nineteenth-century landscapes of the Hudson River School. Hudson River painters such as Albert Bierstadt, Asher B. Durand and Frederic Edwin Church visualised the doctrine of manifest destiny, a philosophy dictating that America’s expansion into the west was both inevitable and virtuous. Their sweeping landscapes drew upon the timeless beauty of rural arcadias found in the English Romantic landscape traditions of John Constable and J.M.W. Turner.20

The scholarship on Pennell has accepted that his naturalisation of the metropolis was simply an attempt to describe the city’s scale and make it artistically viable by using these accepted nineteenth-century English and American archetypes.21 This is partially the case in prints like The Cañon, William Street, where nature was used as a mediator between established artistic subjects and the visualisation of urbanisation. However, instead of his work acting simply as ‘a bridge between past and present’, as Palumbo has claimed, I would argue that Pennell’s New York prints used available tropes to implicate futurity, illustrating a nationalistic aspiration for urban and industrial progress, one which is ideologically affiliated with past depictions of American western expansion into wild nature.22 As Corn has pointed out, writers and artists obsessed by the futurity of New York possessed ‘neither metaphors nor literary forms equal to the newness of their subject’.23 Consequently, Pennell used nature to proselytise man-made material advancement and illustrate a vertical manifest destiny.

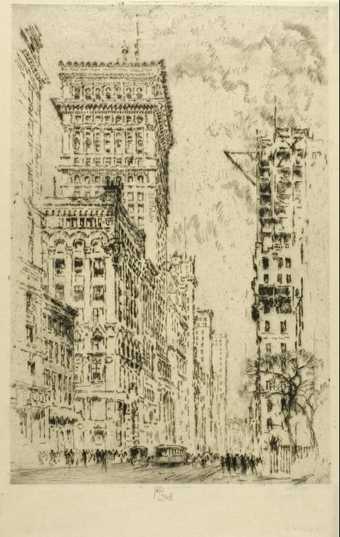

Fig.10

Joseph Pennell

The Golden Cornice, I 1904

Etching with dry point on ivory laid tissue-thin paper

Art institute of Chicago, Chicago

Modernising the picturesque

To further convey the future New York juxtaposed with the old, Pennell often made the city’s impermanence and its constant state of renewal his focus. In his etching The Golden Cornice, I (fig.10), for example, a new building looms on the left while on the right a potential rival already approaches it in height. His prints on the subject of construction, with their fretwork of i-beams and cranes, serve as symbols of the city’s growth, sites where beginnings could be visualised and futures imagined.24 Contemporaneous critical commentary surrounding skyscrapers further reveals New York’s shocking contingency compared to the mood of European cities. Poet Richard Le Gallienne compared the Flatiron Building to the prow of a ship that was ‘lifted to the future. On the past, its back is turned.’25 Likewise, H.G. Wells asserted that in New York, ‘There is no Being but Becoming’.26

Deliberations about how to make sense of the city artistically were rampant in the critical discourse of this period. Pennell’s colleague, the architecture critic Mariana van Rensselaer, defined the picturesque early on in an 1892 article in the Century Magazine as including ‘harmonious and alien elements … of sharp and telling contrasts’.27 She claimed that these characteristics applied to Manhattan ‘in a queer New World fashion’ in ‘a bold, careless, showy way quite characteristic of New York’.28 The ‘toneless’, wide expanses of building surfaces were, according to van Rensselaer, a ‘newer’ artistic problem, and therefore only truly ‘modern’ artists could make sound use of the city’s juxtaposed elements of old and new.29 Aside from the city’s architecture, van Rensselaer made a case for New York’s distinct atmosphere: its sky, lights and even its shadows were ‘crisp’, ‘strong’ and ‘sharp’ compared to the thick, sooty air of London and its ‘dull’ buildings.30 Her statement established a stark contrast between the two metropolises and alerted American, as well as international, readers to the new visual opportunities available in Manhattan. Likewise, photography critic and poet Sadakichi Hartmann’s seminal article ‘A Plea for the Picturesqueness of New York’, written nearly a decade later, argued that artists must seek ‘new laws of beauty’ to depict ‘our modern life … effects which the eye has not yet got used to’.31 One of Hartmann’s solutions was to invite artists and photographers to document the ‘iron skeleton framework’ of skyscrapers under construction. Pennell’s New York prints visually realised these aspirations as he started to forge fresh artistic solutions for this new version of a picturesque spectacle.

Pennell’s celebration of American skyscrapers also facilitated comparisons to London’s anachronisms. Writing in the catalogue to a 1905 exhibition of Pennell’s New York etchings, the artist’s lifelong gallery representative, Fredrick Keppel, disregarded the English art critic John Ruskin’s complaint that the United States had ‘no ancient castles’, declaring that skyscrapers, not castles, were the emblem of American culture.32 In America, wrote Keppel, ‘such sentimentality is generally swept aside: down comes the inconvenient old building and up goes a much better one in its place’.33 To supplement his argument that skyscrapers benefitted society as a whole, while English castles pandered to the constraints of a class-bound tradition, Keppell quoted Jeremy Bentham, the nineteenth-century British social reformer and early advocate for utilitarianism: ‘with us in America … “the greatest good to the greatest number” is the wholesome rule’.34 It is fitting that Keppel used Bentham, who was a leading philosopher of Anglo-American law after the American Revolution, to cross the cultural divide and counteract Ruskin’s case and the cultural elitism of England.

Fig.11

Joseph Pennell

The ‘L’ and the Trinity Building 1904

Etching on laid paper

Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven

Pennell’s print The ‘L’ and the Trinity Building (fig.11) helps to elucidate Keppel’s point. The towering Trinity Building’s southern facade stands opposite the Trinity Church Yard. The church, constructed in 1698 and rebuilt in 1846 by the British-American architect Richard Upjohn, was a symbol of old New York, which Pennell has consciously marginalised by largely excluding it from his cropped vantage point on the elevated railway. According to Keppel, Pennell acted as a witness to America’s emerging cultural icons, documenting Old World nostalgia being replaced by bold new architecture.

Fig.12

Joseph Pennell

The Thousand Windows 1904

Etching

Picker Art Gallery, Colgate University, Hamilton

However, Pennell’s 1904 prints show a merging of traditional modes of representation with experimental choices. For example, by portraying the process of construction in works such as The ‘L’ and the Trinity Building Pennell simultaneously drew upon and subverted the picturesque trope of elegant decaying ruins. In another instance, Pennell’s print The Thousand Windows (fig.12) reprises the variegated mark making and traditional repoussoir of his etching New Oxford Street, London (fig.3), made ten years before, and Whistler’s London prints like St. James’s Street (fig.4). However, unlike both earlier depictions of London, in The Thousand Windows street life is all but omitted with a skyward gaze to emphasise the city’s scale, looming over its anonymous inhabitants, who have been reduced to scribbles. Pennell frequently accentuated New York’s vertiginous character by employing this vantage point, further underlining its difference to lower-rise European streets. Moreover, The Thousand Windows celebrates advancements in engineering necessary to sustain the enormous number of glass windows that give New York its ‘crisp’ and ‘sharp’ edges, which van Rensselaer conceived as the new picturesque. It is evident that Manhattan’s accelerated modernisation, which created an environment physically and spatially opposite to that of London, gradually modified Pennell’s pictorial description of American cityscapes.

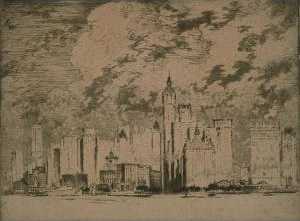

Fig.13

Joseph Pennell

The Unbelievable City 1908

Drypoint etching

Davis Museum at Wellesley College, Wellesley

The second New York set, 1908

The 1904 skyscraper series was a success and was taken up by several British and American magazines of the day. Aside from the Century Magazine article, the Iconophiles book and a 1905 Keppel and Co. booklet, the magazines Outlook, Brush and Pencil and the Craftsman all ran articles reproducing the prints.35 However, the most widely disseminated publication of Pennell’s New York images came in 1909 with John van Dyke’s The New New York: A Commentary on the Place and the People. Pennell had returned to the United States the year prior and produced a series of pastel drawings and 120 prints, which adorned the popular book. A large section dedicated to skyscrapers describes the city from the direction of an incoming transatlantic passenger and compares its dimensions with European cities: ‘The architectural wonders of the world seem insignificant when measured by their [the skyscrapers’] scale … London is cut by church domes and steeples that look down on the low-lying town’.36 By comparing New York to London, van Dyke presents Manhattan as a fantasy world turned into tangible physicality, such that visiting foreigners find their ‘lively expectation outdone by the reality’ at the first glimpse of New York from the water.37 Pennell’s panoramic picture from New York Harbor, titled The Unbelievable City (fig.13), encapsulates this sensation by presenting the graceful metropolis as an aestheticised spectacle emerging from the shore, as if seen from the deck of an incoming ship.38

Fig.14

James McNeill Whistler

Little Venice 1880

Etching and drypoint

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

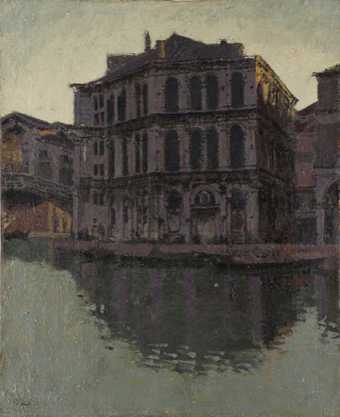

Fig.15

Walter Sickert

The Rialto Bridge the Palazzo dei Camerlenghi 1902–4

Oil on canvas

National Museum Wales

Fig.16

Walter Sickert

Palazzo Eleonora Duse, Venice 1901

Oil on canvas

National Museum Wales

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert

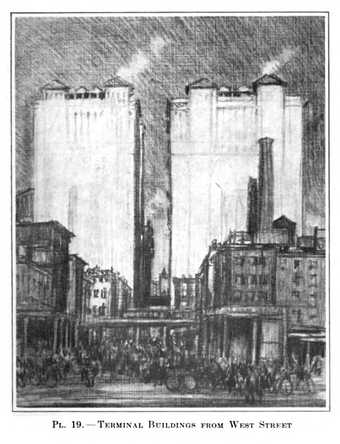

Fig.17

Joseph Pennell

Terminal Buildings from West Street 1908

Halftone print

Reproduced in John van Dyke, The New New York: A Commentary on the Place and the People, New York 1909, pl.19

In his struggle to pictorialise the new metropolis Pennell was forced to turn to what he knew. In addition to impressionist depictions of New York, he was drawn to recent British renderings of Venetian buildings rising above watery canals.39 The elongated horizontal view of The Unbelievable City could be seen as an up-to-date version of Whistler’s panoramic views of Venice from the lagoon (see, for instance, Little Venice 1880; fig.14). However, especially suggestive are Sickert’s Venetian cityscapes, created between 1895 and 1904, such as The Rialto Bridge the Palazzo dei Camerlenghi 1902–4 (fig.15) or Palazzo Eleonora Duse, Venice 1901 (fig.16). The palazzo facades rise from the water, as if from nowhere, similar to many of Pennell’s skyscrapers seen from New York Harbor or from vantage points on the street in the 1908 series, such as Terminal Buildings from West Street (fig.17).

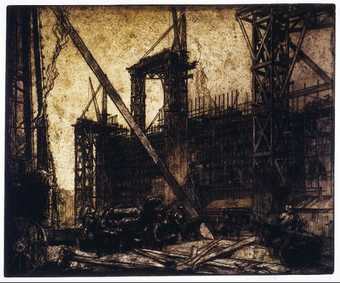

Fig.18

Frank Brangwyn

Building the New Victoria and Albert Museum 1904

Etching with aquatint on paper

Victoria and Albert Museum, London

© Estate of Frank Brangwyn

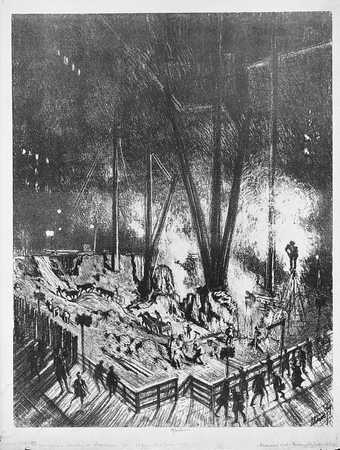

Fig.19

Joseph Pennell

The Foundations, Building a Skyscraper 1910

Lithograph

Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

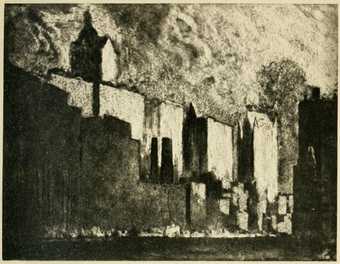

Fig.20

Muirhead Bone

Study for ‘The Great Gantry, Charing Cross Station’ 1906

Graphite and crayon on paper

Tate N02300

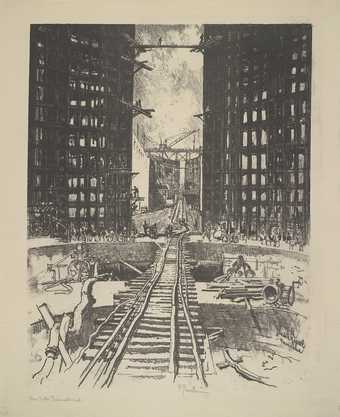

The work of other contemporary British printmakers informed Pennell’s American cityscapes. Later, in the catalogue to an exhibition titled Joseph Pennell and the Wonder of Work held at the Corporation Art Gallery in Bradford, Pennell venerated Frank Brangwyn, Muirhead Bone, William Strang and Frank Short for dignifying urban subjects and the industrial labourer in their printmaking. I stress a particular influence from Brangwyn and Bone, who, in Pennell’s words, cared ‘for the building up and breaking down … the life of the workman’.40 Brangwyn’s etchings of ship builders and workers constructing the Victoria and Albert Museum in London’s South Kensington (fig.18) have a significant congruity with Pennell’s skyscrapers under construction, such as The Foundations – Building a Skyscraper (fig.19). Pennell knew Brangwyn intimately. He respected his lithography especially and had recommended him for several illustration commissions in the past.41 With regard to Bone, his drawing The Great Gantry, Charing Cross Station of 1906 (fig.20) was exhibited at the New English Art Club exhibition from November to December of that year and its subsequent print was illustrated in Campbell Dodgson’s Etchings and Dry Points by Muirhead Bone (1909).42 Pennell’s Under the Bridges, Chicago 1910 (fig.21), and many of his images of unfinished New York buildings, bear a resemblance to Bone’s composition and share with it the allure of industry. Bone went on to visit New York himself and continued to document its construction through printmaking in 1923.43

Fig.21

Joseph Pennell

Under the Bridges, Chicago 1910

Etching

Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

Reconciling old and new aesthetics

In the same way that he regarded skyscraper builders and workers in industrial cities, Pennell identified himself as labourer in his role as draughtsman and printmaker. Pennell’s concept of the ‘Wonder of Work’ is easily navigable throughout his New York cityscapes, which varied from the transcendent upward views of buildings in mid-construction to the blackened foundation pits below street level. Pennell’s pits are either filled with nondescript workers or are absent of them altogether, with only diagonal i-beams jutting in haphazard directions. This view of the city is always done in the name of progress, with workers portrayed not as a mass of proletarian martyrs but as anonymous creators of a commendable achievement. While he utilised British artistic depictions of construction and industrial labour, Pennell’s ‘Work’ attempted to evince an America coming of age against the backdrop of the European Old World. He transformed the city from a naturalised spectacle to one of engineering miracles, accompanied by an increasing emphasis on geometry and hard edges.

The challenge of adjusting timeworn tropes traditionally used to portray European cities to produce an appropriate pictorial language for New York continued to be present throughout Pennell’s criticism. In an article titled ‘The Pictorial Possibilities of Work’, published in the Journal of the Royal Society of Arts, Pennell attempted to prove that art which made ‘work’ its subject (construction sites, industrial factories, skyscrapers) was a continuation of past masters who also depicted urban and working life. Pennell connected this idea with his interest in ‘The Unbelievable City’, writing:

New York, as the incoming foreigner, full of prejudice, or doubt, or hope, and the returning American, crammed with guide-book and catalogue culture, see it or might see it, rises a vision, a mirage of the lower bay, the colour by day more shimmering than Venice, by night more magical than London. In the morning the mountains of buildings hide themselves, to reveal themselves in the rosy steam clouds that chase each other across their flanks; when evening fades, they are mighty cliffs glimmering with glistening lights in the magic and mystery of the night. As the steamer moves up the bay on the left the Great Goddess greets you, a composition in colour and form, with the city beyond, finer than any in any world that ever existed, finer than Claude ever imagined, or Turner ever dreamed. Why did not Whistler see it? Piling up higher and higher right before you is New York … and it is all new and all untouched, all to be done, and save for the work of a few of us, and we are Americans, all undone.44

By comparing New York to Venice and London, and by placing it into the historical idiom of painters such as Turner and Claude Lorrain, Pennell aimed to ennoble the city by associating it with the Old World. However, intermixed with these Romantic references are bolder statements pointing to the new aesthetic possibilities available in New York. ‘The Unbelievable City’ seen from the water is ‘a composition in colour and form’, that is ‘untouched’ and ‘undone’. Manhattan’s unique character, its unfinished physical makeup and perpetual state of renewal, alluded to a future independent of Europe.45

Scholars have shown that artistic depictions of Victorian London displayed similar ideals of future aspirations, which were associated with metropolitan improvements and the demolition of old London to make way for a new imperial city.46 While the redevelopment of London was not undertaken on the same scale as New York, this point further underlines the fact that Pennell’s conception of the American city was subliminally and ideologically linked to the ways in which British artists had visually navigated their capital in past years. New York was the twentieth century’s successor to London’s nineteenth-century power, and like Victorian artists who had chosen subjects from London that celebrated monarchy, nation and empire the century before, Pennell urged his fellow American artists to seek creative opportunities engendered by subjects indigenous to the United States:

In America we have imaginings of Holy Grails, Pied Pipers, Religious Liberties, when one fact in decoration about steel works, sky scrapers, or the Brooklyn Bridge would be worth the lot in the future, when these factless fancies are whitewashed out, or made a good ground to paint on.47

Fig.22

Joseph Pennell

Cliffs of West Street, New York 1908

Sandpaper mezzotint

Reproduced in Joseph Pennell, The Great New York, London and Edinburgh 1912, pl.12

In his 1908 New York prints Pennell devised a fitting aesthetic that could resolve this rupture between aesthetic tradition and the need for a fresh pictorial vocabulary for the equally new metropolis. While The Unbelievable City is a panoramic view, in the series Pennell primarily homed in on individual groupings of skyscrapers. It is the solid massing of indistinct and flattened facades in these works, especially in the 1908 mezzotints, that represents the most significant shift in Pennell’s aesthetic language and one that most scholars have ignored.48 Many of the prints depict exaggerated and vertically elongated skyscrapers made up of flat planes and sharp edges with decreased detailing. At times the skyscrapers are compressed and stylised into slab-like forms or silhouettes, creating matte black or white facades, as is seen in Cliffs of West Street, New York (fig.22).

To achieve his rich and even tones Pennell experimented with a sandpaper mezzotint process, producing effects that foreshadow the abstraction of the Precisionists who responded to the environment in similarly reductive terms. Pennell wrote joyously to his friend Hans W. Singer (keeper of the Dresden Print Room) in 1909:

Whistler is still the man and the artist – I have learned everything from … I am going back to what I learned first – these things are more like my earliest things – they say one harks back – but he did not, he went on and on – only in one way I am trying to go on – that is in big – anyway I am trying for it – but it is so hard – big compositions of these big things – and now though no one has seen them I am trying them in mezzotint.49

His reverting back to his ‘earliest things’ is likely a reference to his five 1894 sandpaper aquatint nocturnes of St Paul’s above the Thames (see fig.7). The mezzotint technique gave Pennell the opportunity to experiment liberally with scale and depth in a similar but far more drastic way to that seen in Whistler’s distorted Thames nocturnes in oil. The 1909 letter sheds light on Pennell’s struggle to reconcile the atmospheric approaches he used to depict London with a more appropriate means of expression for Manhattan’s ‘big things’. His use of a medium that provided a markedly flattened appearance, which focused less on detail and more on a subject’s sheer physical scale, reinforced the idea that New York’s material progress required a new visual language.

Fig.23

Joseph Pennell

Cortland Street Ferry 1908

Sandpaper aquatint

Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

Fig.24

Julian Alden Weir

The Plaza: Nocturne 1911

Oil on canvas mounted on wood

Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

The brazen electrified light in prints such as Pennell’s From the Cortlandt Street Ferry 1908 (fig.23) denies the soft contemporaneous visions of the city produced by American Tonalists like Alden Weir’s New York nocturnes – for example The Plaza: Nocturne 1911 (fig.24) – as well as American impressionist paintings of the city, which possessed a naturalistic sense of depth and retained a traditional Renaissance perspective. Although Pennell did not use mezzotint for long and came to prefer lithography and a more representational style, the 1908 works represent some of the most radical depictions of New York at that time. From the Cortlandt Street Ferry illustrates an abstracted, flattened and elongated New York, more in keeping with aesthetics emerging ten years later in the work of British modernist C.R.W. Nevinson or the American Precisionist Louis Lozowick than any antecedent with whom Pennell may have been familiar.

Pennell’s legacy

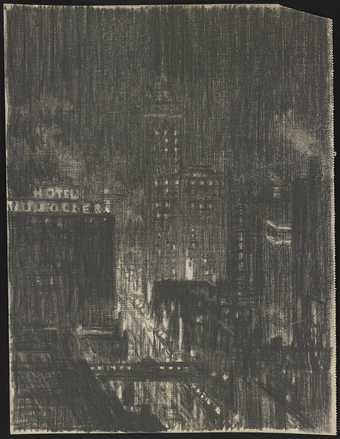

Fig.25

Joseph Pennell

Hotel Knickerbocker, Night Scene 1908–10

Charcoal on paper

Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

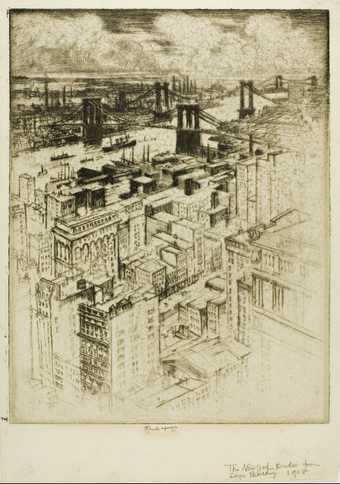

Fig.26

Joseph Pennell

The Bridges 1908

Etching on ivory laid paper

Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago

Pennell’s work in the first decade of the twentieth century encapsulates a transition between the assimilation of machine age subjects to a nineteenth-century idea of the Romantic picturesque, and the embrace of new sensations and aesthetic principles that would preoccupy artists in the coming years. These aesthetic novelties included Manhattan’s inherent geometry, sweeping spatial perspectives and arresting vantage points, looking up from street level and looking down from the dizzying heights of upper stories, as is seen in Hotel Knickerbocker, Night Scene 1908–10 (fig.25) and The Bridges 1908 (fig.26). Pennell’s 1910 description of New York as a ‘composition of colour and form’ has a resonance with the work of later American artists who, in their search for indigenous modern subjects, began to depict the city in vigorous abstract forms. Artworks such as John Marin’s watercolours of 1910, Abraham Walkowitz’s depictions of a fantasy New York and the 1913 cubist cityscapes of Max Weber helped to make iconic Pennell’s unique vantage points, compositional devices and aesthetic choices.50 Such artists undoubtedly knew of his work in illustrated books and magazines such as Scribner’s, Century Magazine, Studio and many others.

Fig.27

C.R.W. Nevinson

The Soul of a Soulless City (‘New York – an Abstraction’) 1920

Oil on canvas

Tate T07448

Fig.28

Joseph Pennell

The Elevated 1908

Lithograph

Across the Atlantic, van Dyke’s The New New York was read widely in Britain. Many of the book’s reproductions, as well as Pennell’s prints and drawings shown in London, influenced the emerging English avant-garde. Following the First World War, transatlantic crossings became easier, and British artists like Nevinson and Alfred Wolmark and the German-born British photographer Emil Otto Hoppé visited New York in 1919. Taken with its architecture’s drama and metaphorical potential to rebuild the social order in the wake of war, the work of each of these artists showed an appreciation of Pennell during these years. Hoppé later admitted that his desire to visit the metropolis came after seeing Pennell’s city prints, which he felt were full of ‘loneliness and grandeur’.51 Likewise, both Wolmark’s numerous vibrant Flatiron paintings and Pennell’s renderings of the building emphasise the city’s unique spatiality by exaggerating the structure’s height. Art historian Ben Jones has found that Nevinson’s celebrated 1920 painting Soul of a Soulless City (fig.27) is probably based on Pennell’s 1908 print The Elevated (fig.28), published in his book The Great New York (1912).52 Both compositions are rendered from the vantage point of an elevated train track that thrusts backward in the direction of fantastical skyscrapers. I would add that this connection is further substantiated if one considers the painting’s compositional likeness to Pennell’s The Gates Pedro Miguel 1912 (fig.29) from his series documenting the Panama Canal’s construction, which shows a miniscule train track centred between the lock’s huge doors.

Fig.29

Joseph Pennell

The Gates Pedro Miguel 1912

Lithograph

Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

Corn’s taxonomy of emerging and evolving portrayals of New York shows that the presence of aesthetic traditions of the past, such as the picturesque, eventually gave way to a more minimalist and reductive aesthetic, which culminated at the end of the first decade of the twentieth century. By analysing Pennell’s renderings of New York and his wider influence in greater depth than in previous scholarship, this essay has demonstrated that Pennell was a major transitional figure within this wider narrative, and his status as a transatlantic artist has been highlighted for the first time in this context. Pennell’s position shows that the dichotomy between old and new New York in his images is fraught with complex meanings and origins. As he sought fresh means of visually constructing the city, Pennell relied in part on contemporary English renderings of urban concentrations in the Old World, as much as on past masters of the picturesque tradition. Pennell’s art and criticism constantly call America’s short history into the limelight through metaphorical allusions to Britain’s more extended cultural past, but his unfinished skyscrapers celebrate the city’s continuity beyond his recorded present moment. As such, Pennell’s celebratory vision of New York helped make the city’s unique futurity an important focus for many artists throughout the subsequent decade.