‘What becomes of eels in the winter, Harnsee?’

‘Go to mud, sir’, answers the broadsman, emphatically.

‘What becomes of eels in winter, Fred?’

‘Bury themselves in the mud’, answers my friend, angler-naturalist.1

What becomes of eels in the winter? This riddle frames the third instalment of Peter Henry Emerson’s ‘Letters from the Norfolk Broads’, a six-part series of literary dispatches that the British naturalist and photographer sent to the Fishing Gazette over the winter of 1890–1 from his houseboat, The Maid of the Mist. Emerson goes on to recount an episode from 4 December, when a sudden thaw released the Maid from the River Waveney’s frozen grip, allowing Emerson and his hired crewman, Jim, to carve a passage from Bungay several miles downriver to Geldeston Lock.2 Emerson describes the conditions on the Broads that winter as ‘Arctic’, an impression supported by official reports, which show that England was in the midst of the coldest December on record, reaching back over 350 years.3 Once the Maid was safely moored beneath Geldeston Lock, the resident lockkeeper pulled open the gates and set down nets in the hope of catching a stray lampern for a shared evening meal. In Emerson’s telling, however, when the lockkeeper returned after several hours to check the nets, he was shocked to discover them brimming with plump silver-bellied eels.

On its face this fisherman’s yarn has evidently little to do with photography, which is the main cultural activity, then as now, on which Emerson’s reputation hangs. The timing, however, invites a kind of allegorical reading. The lockkeeper’s windfall of eels serves to discredit Emerson’s two interlocutors, an outcome neatly foretold by their overconfident replies. Emerson, meanwhile, casts himself as a discerning sceptic, for whom legitimate knowledge only comes by way of direct, unmediated experience. In a wry parting note that plays on Emerson’s epistemic doubts, he quips, ‘I sent our esteemed editor half a stone of these self-same fish. Thereby hangs a tale’.4 Emerson gestures with a wink toward the impossibility of reliably communicating embodied knowledge beyond its corporeal bounds, even as he admits no alternative.

Emerson had been cruising the Broads since 15 September 1890, gathering stories, logging records of weather and wildlife, and making photographs throughout the picturesque network of waterways that had served as his muse since his first visit to the region in 1883. While previous sojourns to the Broads had been purely for leisure, this recent visit also served as an escape of sorts. For nearly two years Emerson had been mired in an increasingly pitched controversy with members of London’s photographic establishment over his provocative treatise Naturalistic Photography for Students of the Art (1889). At the time of its publication in March 1889, Emerson had been honing his ideas on photography for several years, building his reputation through articles, lectures, prize-winning entries at exhibitions and competitions, and a series of lavishly illustrated books beginning in 1886 with Life and Landscape on the Norfolk Broads.5 The highly anticipated release of Naturalistic Photography in March 1889, however, set off a firestorm of heated reviews and exchanges throughout the British photographic press, which by year’s end had spilled across the Atlantic to the clubrooms and journal pages in Philadelphia, New York and Chicago.

Reception and recantation

Emerson initially relished his role as an anti-establishment provocateur. In the November after Naturalistic Photography was published, while serving as the English correspondent for the New York-based American Amateur Photographer, he penned an inflammatory review of the Photographic Society of Great Britain’s annual exhibition, which incensed his British rivals.6 When the London-based Amateur Photographer picked up the review, its editors presented it as an affront to the virtues of his adopted homeland, disparaging it as ‘Dr. Emerson’s un-English “English Letter”’.7

Naturalistic Photography was sweeping in its theoretical, art historical and technical ambitions, but the critical blowback coalesced around his dogmatic assertion that photographs, in order to pass muster as art, should faithfully reproduce scenes ‘as seen by the normal human eye’.8 The basic premise was not particularly new or controversial in itself, to the extent that it was built on a tenet central to British aesthetics since at least the eighteenth century: that artists should strive to imitate nature’s effects rather than copy nature exactly. Instead, it was Emerson’s rather literal interpretation of this dictum that fomented controversy. He had strung together bits of evidence from several scientific texts on human optics, relying in particular on a pair of popular lectures by the German physiologist Hermann von Helmholtz, to justify a method that later came to be known as ‘differential focusing’.9 The technique involved rendering a small area of the image field more sharply than the surrounding details. The resulting effect, Emerson maintained, would account for the influence of the fovea centralis, a small retinal indentation common to humans and other higher primates that produces greater acuity at the centre of the visual field. Where Emerson envisioned a modern system of aesthetics firmly rooted in scientific principles, however, his critics saw fuzzy pictures built on still fuzzier intellectual foundations. Emerson issued a lightly revised edition of Naturalistic Photography in January 1890, but his minor efforts at appeasing his critics went mostly unnoticed, and the tenor of the debate only grew more hostile as the year unfolded.

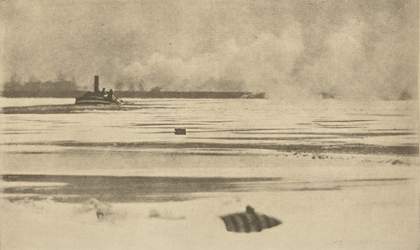

Fig.1

Peter Henry Emerson

The Fetters of Winter 1895

J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

In the Maid’s logbook under 19 December 1890 Emerson describes watching a steamship struggle to break through the ice on Oulton Broad, an incident likely conjured in his 1895 photogravure The Fetters of Winter (fig.1), whereupon he resolved to board a train the next morning to London, reuniting with his wife and then three children for the holiday season.10 During his brief stay in the city he produced a short pamphlet, marked with a thick black border modelled after a death notice, titled The Death of Naturalistic Photography. Addressing his fellow photographers in a histrionic tone that left some questioning his sincerity, Emerson recanted his teachings and withdrew Naturalistic Photography. He mailed copies of the notice to the editors of each of the major British and American photography journals and promptly departed again for the Broads on 19 January 1891, having been in London for a month.11

Emerson’s dramatic recantation of his beliefs about photography and art functions as a pivotal episode in standard retellings of the modernist history of photography. It serves to position Emerson as a hinge between nineteenth-century Victorian and twentieth-century modern aesthetic sensibilities. At the same time, the pamphlet itself is often construed by turns as a poorly conceived and poorly timed parting shot. It acts as the lasting symbol of Emerson’s mercurial temperament, which carries the added irony of pitting him twice against the currents of history – first as a radical and then as a reactionary – since his view that photography deserved recognition as a fine art (certain particulars of his argument notwithstanding) gained favour within the photographic community shortly after he abandoned it. This shift was marked by the formation in May 1892 of the Linked Ring, an exclusive group devoted to the advancement of photography as fine art started by Emerson’s former colleagues.

The Death of Naturalistic Photography in fact contains not a solitary reversal, but a carefully constructed two-part pivot. At the same time that Emerson disavows photography as a legitimate means for producing art, he also casts aside naturalism as a legitimate philosophical basis for art. Failure to recognise that Emerson effectively decouples these two elements results in a skewed understanding of the document. Rather than resting content to accept his rejection of photography on purely technical grounds, as many posthumous accounts have done, a thoroughgoing autopsy requires an assessment of each move on its own terms. By doing so, it becomes clear that considering Emerson’s reasons for disavowing naturalism is essential for appreciating what exactly he was laying to rest.

Emerson concludes The Death of Naturalistic Photography by providing a list of factors that precipitated his change of heart:

Misgivings seized me after conversations with a great artist after the Paris Exhibition; these were strengthened by the appearance of certain recent researches in psychology, and Hurter and Driffield’s papers; and, finally, the exhibition of Hokusai’s work and a study of the National Gallery pictures after three and a half months’ solitary study of nature in my houseboat did for me.12

Among the reasons he provides, the two that have generally garnered attention are his conversations with an unnamed ‘great artist’ and the Hurter and Driffield papers. In the former case, speculation initially centred on James McNeill Whistler, the American expatriate painter living in London, whose atmospheric compositions, coupled with his recalcitrant public persona, Emerson had begun to emulate.13 This interpretation has benefitted from the fact that Emerson shares certain biographical parallels with Whistler, who adopted London as his home in his mid-twenties after spending most of his youth in the United States. Emerson, who was born on a colonial sugar plantation in Cuba to an American father and a British mother, lived in the United States during his early adolescence before relocating to England in 1869 following the death of his father.14 Whistler’s distinctive style drew inspiration from Japanese prints, which also helps to account for Emerson’s reverence towards Hokusai (1760–1849), the influential Japanese painter and printmaker whose work was exhibited for the first time in England at the Fine Art Society gallery on New Bond Street from November to December 1890.15 Despite these various connections, opinion on the unnamed artist has since shifted to George Clausen, a leading British naturalist painter and a founding member of the New English Art Club, with whom Emerson corresponded at length about art and photography, starting in April 1889 and continuing through to July 1891.16

An important scientific paper published in May 1890 by Ferdinand Hurter, a Swiss-born chemist, and Vero Charles Driffield, a British chemical engineer, however, is widely regarded as the main reason for Emerson’s dismissal of photography on the grounds that it was fatally limited in its expressive potentials.17 The pair of Lancashire-based researchers had demonstrated that a fixed relationship exists between exposure and the relative densities of silver deposits on a negative plate following development, a finding that was instrumental in the development of standardised darkroom procedures and reliable exposure aids. Without question, their research dealt a heavy blow to Emerson’s established belief that local tonal relationships could be modified through selective development, an idea that he referenced several times in Naturalistic Photography. For Emerson, this capability was not only important for demonstrating control over the medium, but also, based on his reading of Helmholtz, was necessary to account for the automatic adjustments made by the human eye in response to varying light conditions.

On a more general level, however, Hurter and Driffield’s research had taken what Emerson believed to be intuitive, embodied skills – namely, gauging exposure and controlling tonal relationships – and reduced them to a set of repeatable, mechanical operations that could be mastered with a chart and a slide-rule. The chef, in other words, had been upstaged by the cooks. Yet while Hurter and Driffield’s research doubtless came as a jarring revelation, it ultimately falls short of providing a sufficient explanation for Emerson’s reversal. The paper had no bearing whatsoever on the focus question, and as a result, the very issue that had framed the debate over naturalistic photography had, likely by design, entirely fallen out of view.

Embedded between Emerson’s mentions of the great artist and the Hurter and Driffield papers is a passing reference to ‘the appearance of certain recent researches in psychology’. This veiled comment is so easy to gloss over that it has consistently avoided scrutiny, both in the immediate fallout and since. But given that Emerson’s desire to reproduce human vision was inextricably bound up in psychological questions about perception, it feels deeply significant.

As a medical student at King’s College, London, and later at Cambridge, starting in the late 1870s, Emerson gained exposure to a generation of British intellectuals working in Charles Darwin’s wake who embraced a belief system that came to be known as ‘scientific naturalism’. The term was coined in 1892 by Thomas Henry Huxley, one of the movement’s leading mouthpieces, and he retrospectively applied it to a social doctrine that had taken hold in England during the second half of the nineteenth century.18 The promoters of scientific naturalism, which included prominent intellectuals like Huxley, Francis Galton, Herbert Spencer and John Tyndall, had set out to build a new social and cultural order on a foundation of scientific principles, the theory of evolution chief among them.

Darwin had foreseen the profound impact that the theory of evolution would have on the study of the mind, remarking in the conclusion of On the Origin of Species (1859) that ‘Psychology will be based on a new foundation, that of the necessary acquirement of each mental power and capacity by gradation’.19 Spencer’s The Principles of Psychology (hereafter Psychology), first published as a single volume in 1855 and later revised and expanded into two volumes published between 1870 and 1872, marks one of the first significant forays into evolutionary psychology. Spencer had sought to reconcile evolutionary ideas with the associationist theory of psychology developed by British empiricists, which maintained that the mind operates by linking together simple ideas, ones rooted in sensory experience, to form more complex beliefs.20 To accomplish this goal, he expanded the concept of experience that was central to the empiricist theory of mental formation to encompass the accumulated experiences of an individual’s entire line of descent.21 The result was an empiricist epistemology that in practical terms functioned much more like nativism, the competing doctrine that holds that all mental capacities are innate rather than acquired through experience. Spencer’s Psychology was one of Emerson’s main reference points for understanding psychology, and Spencer’s distinctive rhetorical style is apparent throughout Emerson’s theoretical writings on photography.

Spencer’s evolutionary psychology

On 26 March 1889, directly on the heels of the publication of Naturalistic Photography, Emerson delivered a lecture before the annual conference of The Camera Club, London, on the theme of ‘Science and Art’. The talk was widely reprinted in the British and American photographic press and later became an appendix in the second edition of Naturalistic Photography. Emerson quotes several authorities on science and culture during the talk, including Huxley and the poet and social critic Matthew Arnold, but the bulk of his references, along with the general thrust of his remarks, demonstrate his intellectual debts to Spencer. He begins the talk by conjuring Spencer’s sweeping concept of evolution as a universal first principle characterised by a progressive movement toward greater complexity and differentiation, arguing from this starting premise that art and science naturally become more sharply delineated over time. Then, in a characteristic Spencerian turn, Emerson collapses his descriptive account of an ostensibly natural tendency into a directive aimed at his fellow photographers, remarking ‘It is obvious then, according to the teachings of evolution, that, if we are to make progress, this differentiation must be made, thoroughly understood, and rigidly adhered to by every practitioner of photography’.22

While explicit references to Spencer do not appear in the first edition of Naturalistic Photography, the key section of the book, a chapter titled ‘Phenomena of Sight, and Art Principles Deduced Therefrom’, bears the unmistakable hallmarks of Spencer’s deductive approach to argumentation. Naturalistic Photography is often contextualised as an attempt to bring aesthetics within the sphere of scientific principles – indeed, Emerson himself claimed as much – but read in light of the influence of Spencer’s Psychology, it is perhaps better understood as a philosophical exercise dressed in scientific garb. Emerson begins from a series of generalisations about human eyesight and builds outward, eventually arriving at a series of conclusions about art that are unfalsifiable.

Spencer’s Psychology held a special place in Emerson’s intellectual development. In his autobiographical account of his formative years in medical school, Paul Ray at the Hospital: A Picture of Student Life (1882), Emerson portrays himself as a worldly savant named Reve (‘Je suis philosophe’, he declares).23 The narrative includes lengthy descriptions of the contents of his bookshelf, offering a glimpse into his eclectic reading habits. Spencer’s Psychology, however, turns up at a crucial point in the story and carries the further distinction of being the sole book that Emerson depicts Reve in the act of reading.24 It follows, then, that the references to Spencer in Emerson’s lecture ‘Science and Art’ turn out to have been borrowed from Spencer’s Psychology.

As a justification for his focusing technique, Emerson cites Spencer’s remark that an emotion is ‘vague in its outlines, and has a structure which continues indistinct even under the most patient introspection’.25 He argues that photographs adhering to his method will evince the ‘constructive imagination’, which he notes is ‘the highest intellectual power according to recent psychologists’, another oblique reference to Spencer’s Psychology.26

While Spencer maintained an agnostic posture, claiming that the causal relationship between the mind and the external world is ultimately inscrutable, he repeatedly described mental evolution as an ‘automatic adjustment of inner to outer relations’.27 Based on this formulation, Spencer effectively presented the mind as a passive receiver of sensory stimuli from external nature. From this view Emerson formed his defence of photography as a fine art not so much by arguing, as his modernist successors would, that photography could transcend the mechanistic trappings of the camera through thoughtful, deliberative interventions, but rather by intimating that the human mind itself was reducible to mechanical terms.

The haymaker and the poacher’s art

Emerson’s embrace of scientific naturalism manifested in a number of distinct ways. It led him to view cultural norms and traditions with suspicion, which he applied to art and society in equal measure, dismissing anything that struck him as conventional or artificial. His early social views were decidedly anti-authoritarian and anti-clerical. In art, this same attitude caused him to place a high value on novelty and formal experimentation. He rejected outright the idea that there exist a priori laws of composition, a belief that he equated with ‘the pseudo-scientific pursuits of Phrenology and Astrology’.28 Rather than sweeping composition aside altogether, however, he attempted to turn it on its head, arguing that what is meant by ‘composition’ is really ‘selection’, for which there can be no fixed rules, only underlying principles, since each picture demands its own unique treatment. He maintained that beauty originates in nature, and that the role of the naturalistic artist is to wait until nature appears in one of her ‘propitious moods’ and then passively record the fully formed picture that nature presents.29

Fig.2

Peter Henry Emerson

A Rushy Shore 1886

This passive model of artistic production, which finds a parallel in Spencer’s notion of the ‘automatic adjustment of inner to outer relations’, carries over into multiple aspects of Emerson’s photographic work. In several of his early landscape scenes, for example, such as A Rushy Shore 1886 (fig.2), one can imagine Emerson standing at the water’s edge with no preconceived idea about the picture that he hoped to produce, instead peering at the ground glass and adjusting his camera based on the subtle patterns produced by the reeds on the shallow water.

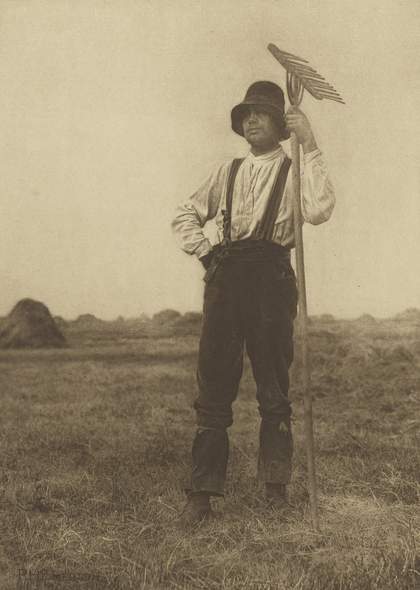

Fig.3

Peter Henry Emerson

Haymaker with Rake (Norfolk) 1888

J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Fig.4

Peter Henry Emerson

Detail of the 1887 proof of Haymaker with Rake (Norfolk), shown alongside the same detail of the final photogravure (fig.3)

National Archives, Kew, ref. COPY 1/379/150A

The search for truth in nature also sheds light on Emerson’s many typological portraits of rural inhabitants of the Broads. In Naturalistic Photography Emerson advised his readers to select models that were at once ‘picturesque and typical’, asserting that one ‘should feel that there never was such a fisherman, or such a ploughman, or such a poacher, or such an old man, or such a beautiful girl, as he is picturing’.30 His methods for achieving this effect are cast into striking relief by comparing a proof copy with the published version of his photogravure Haymaker with Rake (Norfolk) 1888 (fig.3), one of his several homages to the French naturalist painter Jean-François Millet (1814–1875). A remarkable transformation occurs between the albumen proof, which he used to obtain a copyright on the image, and the final photogravure print, which was featured in Pictures of East Anglian Life (1888) (fig.4). In the published version, the expression has been drained from the figure’s eyes and mouth, transforming him into a generic icon of rural virtue.

Fig.5

Frontispiece of Havelock Ellis’s The Criminal 1890

In seeking to blend the picturesque with the typical, Emerson recalls Francis Galton’s method of composite portraiture, which the British statistician first conceived through conversations with Spencer.31 Galton’s technique involved superimposing several portraits of individuals fitting into a certain class in order to generate a generic visualisation of a social or ethnic ‘type’ (see Havelock Ellis’s The Criminal 1890; fig.5). While Emerson expressed reservations about the method, his complaints were technical rather than conceptual – he questioned Galton’s choice of lens and the perspectival accuracy of the resulting composites.32

Figures like Emerson’s haymaker also lend themselves to metaphorical readings as artists according to the framework of naturalism. In the haymaker’s deft hands, the rake manipulates and recombines raw matter into forms that are at once useful and aesthetically pleasing. The act of ‘making’ is here refigured as an act of repurposing what has already been made by nature, for to say that a haymaker ‘makes hay’ is to enact the same semantic inversion by which a photograph – or any work of ‘naturalistic’ art – is ‘made’ rather than ‘taken’.

![Peter Henry Emerson, The Poacher – A Hare in View. [Suffolk.] 1888](https://media.tate.org.uk/aztate-prd-ew-dg-wgtail-st1-ctr-data/images/fig6emersonthepoacher1888.width-420_4BPjTRW.jpg)

Fig.6

Peter Henry Emerson

The Poacher – A Hare in View. [Suffolk.] 1888

J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Emerson’s ideal of artistic production filtered through the lens of naturalism is perhaps best embodied, however, in the figure of the poacher, a recurring character throughout Emerson’s literary and photographic works. For Emerson, the poacher embodied a romantic ideal of a rogue outsider who scorns the conventional norms of society, instead acting in accordance with the laws of nature. He wields keen powers of observation, which helps him to outwit wild game and game wardens alike. In The Poacher – A Hare in View. [Suffolk.] 1888 (fig.6), also included in Pictures of East Anglian Life, the poacher’s tool of choice is a lurcher, whose actions the poacher has mastered. Like the naturalistic photographer, the poacher peers out intently into the landscape, while effortlessly commanding the dog with a leash in his right hand that recalls the pneumatic shutter release used with a view camera. With a single, unconscious reflex, the poacher triggers his tool, releasing the lurcher into the landscape to retrieve the object of his attention.

‘Transfigured realism’

While Emerson was on the Broads, he sent a series of letters to Hurter and Driffield in an earnest attempt to make sense of their research. Buried among his enquiries, Emerson disclosed his attendant concerns about naturalism as a viable framework for art. In a letter dated 26 October 1890 he explained that his ambition had been to visualise ‘the true appearance of things’ rather than ‘things as they really are’. He then confided:

Now in this matter we have to take into consideration physiological and psychological factors. For a naturalistic work is really a work of what Mr. Herbert Spencer calls transf transcendental realism. That is … subjective and objective are intrinsically and transparently connected. It is not the objective only an artist wishes for – that is what the scientist calls for.33

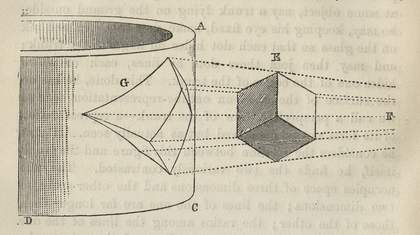

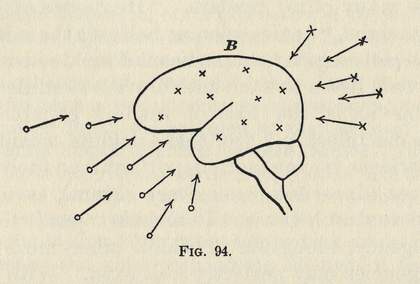

Fig.7

Diagram from Herbert Spencer, The Principles of Psychology, vol.2, London 1872

The phrase Emerson intended but failed to retrieve in the moment is ‘transfigured realism’. The struck-through fragment in the letter suggests that he struggled to recall the appropriate term from memory while on his boat. What, then, is transfigured realism? In a summary section towards the end of Spencer’s Psychology, he returns to his initial premise that there exists a definite, although unknowable, correspondence between external objects and internal mental states. Spencer offers informal proof through a series of thought experiments. He begins by telling his readers to imagine that they are looking through a window at a trunk placed on the ground outside. He directs them to visualise placing a piece of paper against the window and tracing the contours of the trunk. The resulting image, Spencer posits, will register the trunk ‘not as conceived but as actually seen’.34 While Spencer acknowledges that the drawing of the trunk differs from the actual trunk with respect to size, angles and dimensions, he concludes, importantly, that the two are nevertheless connected in a definite way. He follows this exercise with a more abstract example, involving a cube projected onto a curved cylinder (fig.7). Following a similar progression, Spencer reveals that the cube represents an object in the world, the cylinder stands in for the ‘receptive area of consciousness’, and the projected figure constitutes the ‘perception of the object’. He proceeds to cycle through a sweep of realist and anti-realist philosophical positions, conveying each of their essential features before rejecting them in favour of transfigured realism, which he contends draws on elements of each.35 He concludes:

The geometrical analogy thus helps us to see how Transfigured Realism reconciles what appear to be irreconcilable views. It was lately shown that existence, in the accepted sense of the word, can be affirmed only of that variously-conditioned substratum called the Object and that other substratum variously acted on by it, called the Subject; while the effects of the one on the other, known as perceptions, are changes having but transitory existences.36

Spencer argues that both the cube and the curved surface can be proved to exist, and a definite correspondence exists between them, which is reflected in the projected figure. Converting these terms, Spencer thus posits a definite link between mind and matter. While he emphasises that the underlying nature of their correspondence is unknowable, it is easy to see from his progression of examples how Emerson would have arrived at the belief that mental perceptions could be given a concrete visual expression. The first example invites being read as a photographic analogy, with the window standing in for the ground glass of a camera, while the introduction of the curved form in second example, which builds directly on the first, conjures an image projected onto a retinal surface.

Of course, a reference in a private letter – indeed, one that Emerson fails to cite correctly – must not overshadow or outweigh the commentaries on the psychophysical aspects of vision that appear in Naturalistic Photography, which draw not from Spencer, but from Helmholtz. Like Spencer, Helmholtz maintained that little more than a practical correspondence can be said to exist between visual impressions and the objects that inform them. Once again, however, paying careful attention to the particular texts that Emerson read yields additional insights into the conclusions he seems to have drawn. Helmholtz’s complete psychophysical theory of vision can be found in his three-volume magnum opus Handbuch der Physiologischen Optik (Treatise on Physiological Optics), completed in 1867. Emerson appears not to have consulted this larger volume, however; instead, he relied on two popular lectures translated for English audiences, ‘The Recent Progress of the Theory of Vision’ (1868) and ‘On the Relation of Optics to Painting’ (1871).37 While this may seem like a minor distinction, subtle differences in tone and emphasis between the larger work and the condensed lectures are suggestive. In the Handbuch Helmholtz clearly articulates his belief that visual impressions share nothing more than a cursory correspondence with objects in the world. Elements of this view remain in the ‘Recent Progress’ lecture, which were carried over into Naturalistic Photography through Emerson’s statement that ‘the human eye does not see nature exactly as she is, but sees instead a number of signs which represent nature’.38 However, as historian of philosophy Gary Hatfield points out, at the conclusion of the ‘Recent Progress’ lecture Helmholtz takes a decidedly less cautious turn, dangling before his audience the prospect of something more.39 In his closing remarks Helmholtz suggests that by analysing the mathematical relationships between objects, ‘we may indeed look for a complete correspondence between our conceptions and the objects which excite them’.40

That open-ended suggestion, coupled with Emerson’s private appeals to Spencer’s Psychology, supports the view that Emerson initially believed that by registering his visual impression of a scene, he would have succeeded in externalising his inner thoughts and sentiments in a literal sense, a belief reflected in the oft-quoted line from Naturalistic Photography that ‘your photograph is as true an index of your mind, as if you had written out a confession of faith on paper’.41 As an indication of Emerson’s growing doubts about that proposition, however, in August 1890 he submitted in an article that ‘mathematical and artistic perspective are different things’, which he claimed as a new revelation.42 The solid links between visual impressions and inner thoughts and feelings on the one hand, and external objects on the other, which lay at the heart of Naturalistic Photography, were beginning to pull apart.

The theory of evolution, by ostensibly being based solely on observations tied to the natural world, appeared to vindicate the core tenet of empiricism that all knowledge descends from sensory experience rather than innate mental structures. But by showing the eye to be a product of the very processes that it aided in uncovering, evolution also placed a newfound strain on empiricism’s claim to objective knowledge. As literary historian George Levine has observed, following Darwin, ‘the empirical no longer means direct access to the thing in itself but mediated access, through one’s own perceptual equipment’.43

Emerson’s belief that photography could transparently render visual experience, along with his efforts to suppress the role of the imagination and passively adapt to nature, proved increasingly difficult to square with his own lived experiences. In November 1890, while Emerson was away on the Broads, his fifth photographic book, Wild Life on a Tidal Water, was published. The book marked a pronounced stylistic departure from his previous works. Emerson traded the descriptive natural history and ethnography found in his earlier volumes for a self-consciously literary style, inserting himself as a narrator and thereby fully implicating himself as an observing subject.

Fig.8

Peter Henry Emerson

In the Yarmouth River 1890

Royal Academy of Arts, London

Wild Life on a Tidal Water serves as an extended meditation on blurred thresholds – between sea and land, nature and culture, humans and other animals, and ultimately between seeing and knowing. These perceptual ambiguities are represented in the text through recurring zoomorphic motifs: fishermen have flippers, crabs exhibit human vices, sportsmen misidentify birds and vice versa. The same theme carries over into the photographs, appearing in scenes like On Gorleston Sands, where a child digging for crabs resembles a bird engaged in the same pursuit. Emerson presses this morphological ambiguity even further with In the Yarmouth River 1890 (fig.8), where what appear to be two human forms merge into a centaur-like quadruped. As art historian Charles Palermo has argued, Wild Life on a Tidal Water signals an emerging strain of doubt in Emerson, which presaged The Death of Naturalistic Photography two months later.44 By making explicit the observer’s role in the act of observing, Emerson’s photographs, much like Darwin’s theory of evolution, in practice cut away at the foundations of empiricism, making it impossible to deny the role of the observer in the production of knowledge.

Psychology at the Exposition Universelle

The first clue as to which ‘recent researches in psychology’ Emerson was alluding to surfaces in a letter to his close friend, the sculptor James Havard Thomas, dated 26 January 1890. After discussing his preparations for the second edition of Naturalistic Photography, Emerson relates,

I have been reading the reports from La Salpêtrière hospital in France and I fear they are arriving at some terrible conclusions thro’ hypnotism. A normal and perfectly healthy man’s morality can be perverted by a few experiments with a magnet. It opens up a vast field to the psychologists. I’m afraid however that the field won’t be ready enough for our philosophy of art. We were born just 100 years too soon to see the best fun. Recent investigations prove the idealistic brain won’t hold and that all ideas come thro’ the senses.45

Emerson presents these reports as a further vindication of his empiricist psychology. The head of the Salpêtrière hospital at the time, Jean-Martin Charcot, was a leading proponent of hypnotism as a technique for investigating patients suffering from psychological conditions then classified as hysteria. Charcot used photographic imagery to promote his belief that mental states, made manifest through physical expressions, were reducible to mechanistic laws. He published a series of photographs depicting patients in hysterical states in a multi-volume album Iconographie Photographique de la Salpêtrière (1876–80). Emerson was aware of Charcot’s photographic studies and their relevance to art, making reference to them in one of his first public lectures on photography in 1886, but these new reports involving magnetism appear to have given him a new sense of pause.46 This passage from Emerson’s letter thus puts forth a compelling candidate for the ‘recent researches’ that Emerson alluded to in The Death of Naturalistic Photography. However, settling on the reports from the Salpêtrière as the likely point of reference raises the question: given that they seem to corroborate Emerson’s naturalistic view of the mind, on what grounds would they have challenged his pre-existing beliefs?

While Emerson’s letters to Thomas do not offer any further clarity, lining up the chronology of Emerson’s private and public statements yields a plausible explanation. The following week, an essay by Emerson titled ‘Topography and Art’ appeared in the Photographic Art Journal. It begins with an anecdote that Thomas shared with Emerson one evening while the two were discussing scientific views toward art. Thomas had related to Emerson a recent encounter that he had with William Benjamin Carpenter, a prominent British physiologist. Carpenter had commented to Thomas on the beauty he saw in a photograph of a cave that he had once visited. Thomas demurred, saying that it was not a ‘picture’, to which Carpenter replied, ‘I know nothing of that, but the photograph gives me great pleasure’.47 In Emerson’s essay, the story serves to illustrate a distinction between the pleasure derived from personal associations with the objects of representation and genuine aesthetic pleasure.

Historian of photography Mary Warner Marien has pointed out that Emerson’s subsequent analysis in the essay leans on a specific passage in Carpenter’s Principles of Mental Physiology, which describes how emotional responses can arise automatically by calling to mind past experiences. This idea signalled a new, although as yet not fully developed, departure in Emerson’s thinking. Read in conjunction with the reports from the Salpêtrière, it suggests that Thomas may have succeeded in complicating Emerson’s understanding of how sense impressions operate in the mind, by showing that once they become embedded as ideas, they gain autonomy and can be reanimated by various means. While Emerson could still claim that hypnotism validated his empiricist viewpoint, crucially, these new developments created the possibility of an independently acting mental architecture. As a further indication that this general premise embodied a meaningful shift in Emerson’s thinking, he included ‘Topography and Art’ as an appendix in the third and final edition of Naturalistic Photography.48 In Thomas’s reply to Emerson’s letter, he indicates that they had recently attended the Exposition Universelle in Paris together, which, viewed in light of the conversations they were engaged in, presents a case, though inconclusive, for thinking that Thomas may have even been the ‘great artist’ who had played a role in unsettling Emerson’s convictions.49

It is doubtful that the exact reports that Emerson encountered can be ascertained, but the timing of the letter also suggests that he may have been reading accounts from the Paris Exposition Universelle, which not only featured art, but also marked a watershed in the history of psychology. The Exposition played host to the first International Congress on Physiological Psychology, which took place from 6 to 10 August 1889. The purpose of the congress, which brought together a delegation of representatives from twenty-one countries, was to establish psychology as an independent discipline. Charcot was initially slated to preside over the event, but he did not attend, devoting his energy instead to a parallel event, the first International Congress on Hypnotism. The congress on psychology featured an International Advisory Committee, comprised of leading researchers from Europe, including notables in the burgeoning field like Helmholtz, Galton, Wilhelm Wundt, Alexander Bain and Pierre Janet, along with a single committee member who had travelled from the United States: the Harvard professor William James. James played a prominent role in the event and he wrote an official report on the proceedings for the British journal of philosophy Mind.50 In the summary account, James indicated that an unfavourable consensus had formed around the theories of the Salpêtrière school, making it unlikely that Emerson was referring to his report, but the general interest in hypnotism was apparently so strong at the event that several sessions reserved for other topics were given over to it.51

After returning to the Broads in January 1891, Emerson co-authored a paper with his occasional collaborator, the painter Thomas Frederick Goodall, entitled ‘Notes on Perspective Drawing and Vision’. Emerson and Goodall set out to demonstrate that conventional techniques of linear perspective do not correspond to vision, offering a series of informal proofs, along the lines of looking at a landscape through one’s legs or holding up two slips of paper at various distances from one’s eyes.52 The paper briefly reignited the debates that had formed around Naturalistic Photography. One critic suggested that a discussion rooted more in psychology would have been more effective than the casual proofs offered in the paper.53 Emerson’s rejoinder demonstrates his recent investment in psychological issues:

Mr. Wheeler says, ‘the accepted mental theory, according to which distance can never be directly seen as such – that is, it can never be apprehended as simple sensation’. Now Mr. Wheeler shows by his remark that he knows nothing of the will of the ‘sensationalist’, by whom the third dimension is considered to be a pure sensation … [Wilhelm] Wundt’s life has been spent in constructing a space theory, to my mind valueless, and I can say again, with one of the profoundest living psychologists, who emphatically calls ‘Wundt’s “theory” the flimsiest in the world’. So much for Mr. Wheeler’s only accepted theory. I have shown the sensationalists have another theory. Finally, all I have to say is, that since Mr. Wheeler seems innocent of the literature written against Wundt, Helmholtz, and Co., it is useless to open a discussion. It only remains to state our observations are in no sense ‘judgments’, but pure sensuous impressions. Finally, I would recommend Mr. Wheeler to the works of Stumpf, Schön, Volkmann, Hering, and others.54

The psychologist whose name Emerson omits is in fact William James, and the text he quotes is the chapter titled ‘The Perception of Space’ from James’s monumental, two-volume work The Principles of Psychology (hereafter Psychology). James’s Psychology, a project twelve years in the making, debuted on 26 September 1890, shortly after Emerson had departed for the Broads. While copies of James’s Psychology did not arrive in England until late December 1890, all but ruling out the possibility that Emerson had read James’s Psychology prior to publishing The Death of Naturalistic Photography,55 ‘The Perception of Space’ would have been accessible, having been published serially in Mind in 1887.56 Emerson’s recommendations for further reading are lifted nearly verbatim from James, suggesting that he did not actually consult them, but instead seized on an opportunity to stack names in his favour.57 The issue that Emerson raises, in which he now finds himself at odds not only with Helmholtz and Wundt, but also Spencer, involves an esoteric though spirited debate among psychologists over whether space, or ‘extension’ as it was then often called, constitutes an intrinsic quality of objects or a conventional sign that formed by means of a mental action, or a ‘judgement’, taking place in the mind.58

James’s critique of Spencer

Mapping the nuances of James’s views on spatial perception onto Emerson’s beliefs about vision would be difficult and ultimately somewhat foolhardy, given Emerson’s penchant for glossing over certain particulars in service of his larger argument. In essence, however, by proposing that spatial relationships are primary qualities of objects, James rebuffed the prevailing view among British and German psychologists that spatial perception forms as a secondary quality through an automatic mental process, something which Helmholtz called an ‘unconscious inference’ – a term that curiously merges passive and active elements in a manner similar to Darwin’s phrase ‘natural selection’.

James devoted significant energy in his Psychology to discrediting Spencer’s Psychology, a point he impressed by giving his work the identical title. The main criticism that James levied against Spencer concerned the latter’s contention that mental architecture was formed entirely through automatic adjustments to inputs from the environment. James initially outlined this critique in an essay titled ‘Remarks on Spencer’s Definition of Mind as Correspondence’ (1878), essentially arguing that Spencer’s model amounted to a perverse mixture of environmental and biological determinism.

Fig.9

Diagram of the human brain from William James, The Principles of Psychology, vol.2, New York 1890

James summarised his key grievance in his Psychology through a schematic diagram comparable to Spencer’s cube and cylinder illustration (fig.9). Using a series of ‘X’s and ‘O’s to illustrate two distinct classes of mental phenomena, James argued that some ideas enter consciousness directly through the senses, but other, abstract ideas – the examples he gives include the pleasure we derive from music and the feeling of loneliness – do not bear a direct resemblance to objects in the world. Building on this observation, James mused that ‘Our higher aesthetic, moral, and intellectual life seems to have entered the mind by the back stairs’.59

Crucially, James’s disagreement with Spencer was not so much about the validity of joining the theory of evolution to the human intellect, but rather about how to interpret the influence of evolution appropriately. James challenged Spencer’s evolutionary psychology by working within the same parameters that Spencer had set forth, offering an explanation for how the mind can assert its own agency, while still falling within the laws of organic evolution. In James’s view, Spencer had wholly ignored the role that chance and accident, key features in Darwin’s theory of evolution, played in mental development. These elements, in turn, supported the possibility of what James called ‘psychogenesis’, or the spontaneous development of ideas within the mind, independent of any external stimuli.60 Much like James, Emerson did not cast aside his underlying philosophical commitments to naturalism, but rather had arrived at a more nuanced understanding of how a naturalistic epistemology might work, one that carved out an independent role for the imagination, through which ideal conceptions could emerge that did not directly correspond to things in nature.

Emerson planned his return to the Photographic Society of Great Britain in 1893 to deliver a speech meant to revive naturalistic photography through revisions based on his new insights. (He was not able to deliver in person due to the death of his brother, who had settled in Florida.) In the speech he declared that while photography necessarily falls short as an expressive medium, photographers should still strive to make their images ‘decorative’ while, as far as possible, creating the ‘illusion’ of an impression of nature. Emerson’s use of the term ‘decorative’ underscored his turn to Whistlerian aesthetics, no longer believing that art must follow nature exactly. His use of the term ‘illusion’, however, owes a direct debt to James.

Emerson quotes again from James in this 1893 lecture, amid a discussion of various optical illusions.61 Omitting James’s name again, he indicates that the quote was excerpted from ‘a text-book on Psychology, published only last year’, referring to an abridged edition of James’s Psychology.62 Given that Emerson had read ‘The Perception of Space’ prior to 1892, his decision to quote from a modified version of the text while emphasising its recent publication date is perplexing. Perhaps he wanted to convey the impression that he diligently kept up with current research. He may have also wanted to convey that his crisis of faith had come as a response to new research, rather than insights spelled out as early as 1887, several years before the publication of Naturalistic Photography. Where Hurter and Driffield’s research had blindsided Emerson, overturning a factual belief about photography that he had taken for granted, the revelations from James by contrast revealed a critical error in the very conceptual underpinnings of his project. Placing greater emphasis on the Hurter and Driffield papers thus enabled Emerson to save face by framing his pivot primarily as a response to newly available empirical data.

Fig.10

Peter Henry Emerson

Marsh Farm in Early Spring 1893

J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

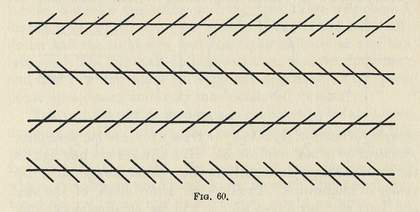

Fig.11

Diagram of Zöllner line illusion from William James, The Principles of Psychology, vol.2, New York 1890

Following The Death of Naturalistic Photography Emerson went on to publish two additional photography books – On English Lagoons (1893) and Marsh Leaves (1895) – yet he stopped producing new photographs in any significant capacity following the stint on the Broads from January to August 1891. None of the plates appearing in these final books postdate that time.63 The distinctive focusing effects visible in many of the plates, which decidedly differ from the effects in prints from his earlier books, are an indication of the new lens arrangements that he had begun to experiment with on the Broads starting in the autumn of 1890.64 Most modern accounts of Emerson’s career call attention to the way that the ethereal landscapes appearing in these final books signal a turn toward a sensibility concerned with interiority, which follows from his embrace of Whistler. Returning to those plates with Emerson’s new views on psychology in mind, however, presents an alternative interpretive framework for viewing many of the prints based on visual illusionism. In Marsh Farm in Early Spring 1893 (fig.10) from On English Lagoons, for example, the horizon and the plough lines in the foreground appear subtly askew, creating a sense of upward movement. The orientation of the horizon and the lines formed by the ploughed field in the foreground suggestively recall the Zöllner line illusion that James reproduced in ‘The Perception of Space’ (fig.11). Other plates, such as A Daughter of the Marshland 1893 (fig.12), also from On English Lagoons, suggest a softened naturalism, one that is less concerned with physiological types and more receptive to spontaneous individual expression. This portrait, which is unlike any other of Emerson’s published images, depicts a woman gazing directly at the camera, exuding a warm, self-possessed contentment. It invites speculation about what kinds of work Emerson would have produced had he decided to remain active in photography.

Fig.12

Peter Henry Emerson

A Daughter of the Marshland 1893

When Emerson wrote Naturalistic Photography he was confident that, following recent advancements in psychology, he would soon be able to pry apart the gates of the mind, allowing him to peer in and discover the proverbial wriggling mass of silver eels contained within. When he rescinded this view, he did so in part because he had come to accept that psychology was as yet in its infancy. While the proofs that he called forth in ‘Perspective Drawing and Vision’ read like quaint exercises, in another sense they signal a shift in his rhetoric away from the Spencerian model of deductive reasoning toward the emerging norms of experimental science, which sought to integrate standards of falsifiability. At the same time, Emerson had relinquished the belief that photography is capable of genuinely reproducing vision. Tellingly, in the third and final edition of Naturalistic Photography, which was issued by an American publisher in 1899, Emerson commuted his remark on photographs being a ‘true’ index of the photographer’s mind, replacing it with a decidedly equivocal ‘rough index’.65

Emerson’s rejection of the coarser naturalism also coincided with a more general waning of Spencer’s influence, even among the proponents of scientific naturalism. In May 1893 Huxley delivered a high-profile lecture at Oxford on the theme of ‘Evolution and Ethics’. The speech marked a significant break from Spencer over the idea that evolution could be turned into an instrument of social progress. ‘Some day, I doubt not’, Huxley reflected, ‘we shall arrive at an understanding of the evolution of the aesthetic faculty, but all the understanding in the world will neither increase nor diminish the force of the intuition that this is beautiful and that is ugly.’66 Like Huxley, Emerson remained optimistic about what future insights into aesthetics that psychological research might yield, but he ultimately came to realise that aesthetic judgements, no less than ethical ones, cannot be explained away by appealing to the evolutionary struggle for existence. For Emerson, this recognition that there may be no universal aesthetic standards left him with no solid ground to turn to in his artistic practice.

In a recent assessment of Emerson’s legacy, art historian Douglas Nickel reflected that by following Helmholtz in recognising vision as a deeply embodied act, Emerson fits within a broader historical shift at the end of the nineteenth century toward notions of interiority, a trend that Nickel associates with the works of several modernist luminaries including, suggestively, William James.67 That stands as a valid, if not prescient, appraisal of where Emerson ended up. It must be emphasised, however, that Emerson arrived there reluctantly, and only after he had relinquished his most deeply held beliefs about psychology and art, on which he had staked his career in photography.