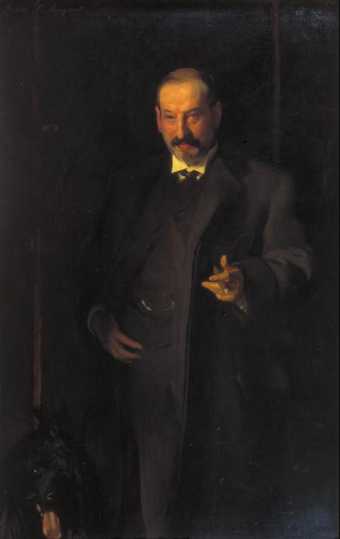

Fig.1

James E. Purdy

Photograph of John Singer Sargent 1903

Sepia matte photograph

National Portrait Gallery, London

© National Portrait Gallery, London

In November 1903 the art writer Evan Mills penned ‘A Personal Sketch of Mr [John Singer] Sargent’ (see fig.1) and published it in the New York journal World’s Work:

Mr John Singer Sargent is a typical example of the modern cosmopolitan man, the man whose habits of thought make him at home everywhere and whose training has been such as to preclude the last touch of chauvinism. Such a man has only become possible during the last fifty years and then only in the case of an occasional American … In the case of an American born and bred abroad, the only feelings that can possibly arise are those that come of cold selection [since] he is unattached to anything.1

In his three-volume study of The History of Modern Painting, published in Munich in 1893–4, and translated into English in 1896, the German Professor of Art History at Breslau University and Keeper of Prints at the Munich Pinakothek, Richard Muther, tried to locate Sargent’s place as an American artist within the development of modern art. He concluded that:

Sargent is one of the most dazzling men of talent of the present day … He is the painter of subtle and often strange and curious beauty, conscious of itself and displaying its charms in the best light – a fastidious artist of exquisite taste … Sargent is French in his entire manner.2

At the 1900 Paris Exposition Universelle, Sargent – like his compatriot artists James McNeill Whistler, Edwin Austin Abbey, Mark Fisher and Frank Millet – elected to exhibit in the United States section although resident in the United Kingdom. The British authorities registered a fierce complaint about the positioning of these artists within the American section, believing that domicile overrode nationality.3 Stoking American outrage, the art critic Royal Cortissoz in the New-York Tribune in July 1900 responded that while Sargent’s art might not seem ‘American’, it had ‘the freshness and sincerity’ and ‘sanity as well as vigour’ that characterised the emerging American School; an art devoid of the ‘over-civilised’ and ‘over-sensitive’ signs of European assimilation.4 Providing visual reinforcement for claims about American racial distinctiveness, Cortissoz proclaimed that ‘the [paintings] have nothing to identify them with any other school. They are original works of genius, their authors are American’.5 Later citing evidence that Sargent’s Yankee forebears had provided him with ‘his keen objective vision … and expertness of … hand’, he concluded that Sargent’s cold ‘detachment’ was proof that he ‘belongs to us, and there’s an end to it’.6 The American art writer Christian Brinton, in his survey of Modern Artists published in New York in 1908, went even further arguing that ‘Sargent’s art is neither Gallic nor British, it is American’ and ‘so dazzled has the majority been by its cosmopolitanism that the real racial basis of his nature has been overlooked’.7

In 1910 the British-Jewish artist of Anglo-German descent William Rothenstein, considering the English sculptor Eric Gill’s decision to decline the German aristocrat Count Harry Kessler’s offer of help in arranging for him to study in Paris with the important French sculptor Aristide Maillol, wrote to Gill that Kessler ‘is such a keen & such a good fellow, but still he is cosmopolitan, & cosmopolitanism has not been good for Germans, & I don’t think it is a good thing for us’.8

Lastly, the British artist and art critic Walter Sickert, reviewing the Third Exhibition of Fair Women organised by the International Society of Sculptors, Painters and Gravers at the Grafton Galleries in London in the New Age in June 1910, recognised the growing trans-national currency which French-derived impressionism had achieved. Impressionist style, as adopted by a range of international artists, led Sickert to declare, ‘How far we have travelled in our ideals of portraiture! … Alas! We are all cosmopolitanised’.9

These six quotes from c.1893–1910 open out onto a revealing, if contested, historical critical terrain between cultural nationalists and internationalists, in which the term cosmopolitan and its interconnection with national and racial identities, cultural stereotypes, citizenship and domicile is complicated, shifting and confusing.10 When deployed to try and explain the correlation between Sargent’s expatriate experience and his works’ perceived sense of ‘detached’ mental estrangement, these quotes seem at odds with each other and strangely contradictory. For Mills, Sargent is the modern cosmopolitan American man, well-travelled and highly cultivated, but whose lack of familiarity with American culture produces a cold, detached sensibility. For the German Muther, Sargent, American by nationality if not by birth, produces modern art that is really French in its cultural affiliation (Sargent trained in Paris) but which was characterised by a ‘fastidiousness’ and an often ‘strange and curious beauty’.11 For the Americans Cortissoz and Brinton, it is the sense of physical and mental detachment evident in Sargent’s work that distinguishes it as racially American and that validates his inclusion in the American section in the Paris Universal Exposition in 1900. By contrast, for the Anglo-Jewish painter Rothenstein, cultural cosmopolitanism is to be avoided at all costs since it is detrimental to German (and British) national self-determination and undermines any sense of national character in modern art. Kessler’s ‘cosmopolitanism’ threatens to undermine his admirable German aristocratic character making Gill’s refusal to travel to Paris to learn French sculptural techniques and entertain Francophile aesthetics, in Rothenstein’s eyes, the correct decision. And for Sickert, any signs of cosmopolitanism in portrait painting signalled a commitment to a jaded artistic lingua franca in which younger artists had imported powerful pictorial styles from Paris that were detrimental to localised British traditions and undermined the valued conventions of portraiture.

What this article will examine is the problematic status of cosmopolitanism as it was applied by British and American commentators to Sargent’s portraits and figure paintings. I will argue that these differences in approach vividly expose the altering transnational dynamics of the art market and its shifting critical terrain between c.1886–1926; the period from March 1886 when Sargent made his home permanently in London and the British art market became his main focus, to the year after Sargent’s death on 15 April 1925 when large memorial exhibitions and the opening of the Sargent Galleries at the Tate Gallery in London in June 1926 forced a re-evaluation his artistic legacy and his art’s national allegiance.12 My article will demonstrate that these questions about Sargent’s national positioning and the contested value of ‘cosmopolitanism’ in art emerged most forcefully at the 1900 Paris Exposition Universelle as American writers aggressively inserted Sargent’s work into a founding and celebratory, if eclectic, American art historical narrative that British reviewers disputed. Moreover, this critical scepticism about Sargent’s works’ worth and its contested cultural affiliation resurfaced again at the time of the three large memorial exhibitions in 1925–6 at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and the Royal Academy, London when critics in both countries re-evaluated Sargent’s posthumous artistic legacy, the artist’s cultural identity and his art’s national allegiance.

Initially, I want to investigate how Sargent’s background, personality and eclectic tastes presented difficulties for English and American art writers as they evaluated the new type of artist he represented; one actively working in the 1880s strategically across the London and Paris art markets and exploiting the commercial opportunities that these rapidly changing transnational art economies presented. What emerges is how the formal and technical features of Sargent’s portraits, from the artist’s permanent relocation to London from Paris in 1886, were seen to register unsure and divergent national allegiances derived from his expatriate experience that, depending upon the context of their display and the cultural contingencies of their reception, were either critically praised or severely criticised.

Born in Florence on 12 January 1856 to expatriate American parents of independent means who travelled extensively throughout Europe, Sargent trained at the Ēcole des Beaux Arts in Paris from October 1874 studying under Emile Carolus-Duran. Despite having sent important works to the Royal Academy shows before coming to London – namely Dr Pozzi in 1882, Mrs Henry White in 1884 and Lady Playfair in 1885 – it was only in March 1886 that Sargent moved permanently to London and that the British art market became his main focus, although Sargent continued to show regularly in Paris.13 As Sargent clearly recognised, his use of continental typologies and his Beaux-Arts style were seen as a liability by British critics since although, ‘there is more chance for me … as a portrait painter [in London] … it might be a long struggle for my painting to be accepted. It is thought beastly French’.14

Fig.2

John Singer Sargent

Vernon Lee 1881

Tate

Crucially, this relocation to London gave British art critics the opportunity to learn more about the man himself and they characterised him as an odd, multicultural melange having a chameleon-like ability to fit in to London life. For Americans such as the historian Henry Adams, Sargent was also seen as a curious expatriate amalgam and ‘one of those Americans who catch English manners’.15 Even his life-long friend Violet Paget, better known as the writer Vernon Lee, whom Sargent had painted in 1881 (Tate N04787; fig.2), recalled that at first meeting Sargent seemed more French than English: he was ‘very stiff, a sort of completely accentless mongrel … [with] rather French faubourg sort of manners’.16 Other contemporaries acknowledged that Sargent was difficult to fathom seeming as ‘a sepulchre of dullness and propriety’ who in public presentation reminded them of ‘a character [somewhere] between General Kitchener and a superior mechanic’.17

Sargent’s residency in London allowed English art critics to see his work at first hand in order to evaluate its particular cultural attachments. The initial critical reception focused on the artist’s French training and his study with Carolus-Duran (1837–1917) and, in particular, assessed Sargent’s technical dexterity and his paintings’ bravura stylistic manner. As a result, many English commentators felt his work was more French in style than English and they mistrusted its non-exclusive attachment to either culture. This conflicted interpretation was confirmed in British evaluations when Sargent exhibited six portraits and six subject paintings at the Paris Salon between 1877 and 1882 to great acclaim.18 As the English art critic Claude Phillips reviewing ‘The Americans at the Salon’ in 1887 acknowledged, Sargent’s artistic francophilia was not always applauded in London: ‘Mr J.S. Sargent, so lately an idol of the fickle Parisians … has migrated to England where, as will be the recollection of all, he has clearly “imposed” himself with surprising success considering the uncompromising character of his style’.19 For his English supporters, however, Sargent’s ‘uncompromising style’ was a praiseworthy and sophisticated art of technical brilliance derived from his Paris training that embodied what the London Illustrated News praised as the ‘Franco-American school at its best’.20

For his detractors, Sargent’s fashionable portraits with their dazzling French handling and continental models were considered suspect and criticised as ‘too risqué’, ‘slick’, and ‘flashy’ and flaunting an especially dubious, foreign-inspired aestheticism when practiced on British sitters.21 For example, when Sargent’s portrait of The Misses Vickers 1884 was displayed at the Royal Academy that year, it was disparaged by the Spectator critic Harry Quilter as overly dispassionate and superficial: ‘the French method as learned by a clever foreigner, in which everything is sacrificed to technical considerations … [The artist] seems never to have felt at all that there was anything more in its subject than a good opportunity of displaying the painter’s power.22 Alongside Sargent’s continued showing at the Paris Salon, the regular exhibition of his work at the New English Art Club (NEAC) from 1886 to 1894 and at the New Gallery – major venues for the display of work by young Anglo-French artists in London – confirmed this Francophile alliance, even though Sargent’s work suggested less formal affiliations than they often perceived.23

Fig.3

John Singer Sargent

Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose 1885–86

Tate

These claims and counter-claims over Sargent’s cultural attachments shifted in 1887, when Sargent’s Royal Academy submission, Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose 1885–6 (Tate N01615; fig.3) met with critical applause from many English critics and the work was bought by the Chantrey Bequest, substantially raising the artist’s public profile in Britain. The year 1887 marked out a positive turn in attitudes in England towards French impressionism since as the Artist critic recognised ‘Impressionism in some form or another is becoming the central idea in a very large proportion of modern pictures production’.24 In May 1889 Sargent showed his A Morning Walk 1887 and St Martin’s Summer 1888 at that year’s NEAC exhibition where their close relationship to works by Claude Monet registered.25 Although set in an English, not French, landscape setting, as art historian Elaine Kilmurray has noted, A Morning Walk more than any other painting signalled Sargent’s indebtedness to Monet’s work by making direct reference in subject, viewpoint, colouring and handling to two recent works by Monet: Essai de figure en plein air, vers la droite and Essai de figure en plein air, vers la gauche, both painted in 1886.26 The Magazine of Art critic declared rather obviously that both the Sargent works were ‘painted under the direct inspiration of Claude Monet’, whose paintings, exhibited at a solo show in London at this time, supported this direct allegiance.27 Not unsurprisingly, the ‘New Critics’ such as R.A.M. Stevenson, George Moore and D.S. MacColl, who actively supported French impressionism and its British adherents applauded Sargent’s surface effects, looser handling and heightened colouring that, in their eyes, explicitly confessed his cosmopolitan aesthetic.28

If Sargent’s standing in Britain was more secure by 1887, from 1886 he had begun exploiting the sales opportunities provided by the growing trans-Atlantic art market for impressionism. Alert to these commercial prospects, French dealers had opened galleries on the East Coast and American dealers started to negotiate Franco-American commercial alliances in the second half of the 1880s. Most prominently, the Paris dealer Paul Durand-Ruel went to New York in March 1886 and launched his gallery at 28 West 23rd Street in Manhattan in April 1887.29 Similarly, the French dealer Bousson, Valadon & Co. established a gallery in New York a year later in 1888 to sell French impressionist paintings. Aware of such commercial opportunities, Knoedler in New York also tried to establish a Franco-American partnership with the dealer Alphonse Legrand in 1886.30 Awareness of this trans-Atlantic demand for impressionist work led to American dealers such as the American Art Galleries entering the market and displaying works by leading French artists in New York. The gallery’s opening show (10–25 April 1886) featured 289 Works in Oil and Pastel by the Impressionists of Paris.31

Fig.4

John Singer Sargent

Henry G. Marquand 1897

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

© Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Sargent’s more sustained engagement with buyers and dealers on the East Coast marked out a savvy trans-Atlantic strategy that was in part a response to the French art market collapse from c.1882–3. Consolidating his growing reputation in London, he exploited his contacts in Boston and New York and began exhibiting more work in prestigious art circles in the United States.32 For example, in 1886 Sargent had been elected to the selection committee of the Society of American Artists and he exhibited at its Ninth Annual Exhibition in New York from May to October two American portraits Mr and Mrs W. Field 1882 and Mrs Wilton Phipps c.1884. In August 1887 the influential New York banker and collector Henry G. Marquand, whose portrait Sargent was to paint later in 1897 (fig.4) had invited the artist to paint his wife’s portrait.33 This request led to Sargent’s first trip to the United States in the following month which Sargent saw as ‘a turning point in my fortunes’ there and facilitated his first successful solo exhibition at the St Botolph Club in Boston from 28 January to 11 February 1888, one of the most influential private members clubs devoted to the Fine Arts in the United States.34

Yet American critics also remained unsure about Sargent’s ‘paternity’ and why it had taken the artist so long to return to his native land. The Art Amateur critic reviewing Sargent’s showing at the portrait exhibition in Boston in 1888 questioned:

Mr. Sargent, everyone knows, is a distinguished painter, even in Paris … But it does not follow that Boston, which prides itself on an art culture very different from that of the contemporary Salon … will think more of him for that. [He] is the member of one of the most distinguished of old Boston families, but he has had the temerity to absent himself from his native country from the day he was born up to within two months of this exhibition.35

Fig.5

John Singer Sargent

Claude Monet Painting on the Edge of a Wood ?1885

Tate

Similar consternation was expressed about his works’ perceived allegiances as the critic Clarence Cook noted: ‘whatever he exhibits becomes at once the centre of interest and is discussed with energy, often with heat, alike by artists and laymen … and yet, for an artist so strong in his technique, his pictures show a singular lack of individuality … We wish we knew what Mr. Sargent really is as a painter. He wears so many masks, and plays, with ill-concealed delight, so many tricks.’36 Nevertheless, appreciated at first hand, many American critics applauded Sargent’s American portraits, and his Venetian scenes and landscape studies were seen as part of a growing interest in impressionist landscape painting and shifting light effects, but practiced by an American painter. Such cultural attachment was confirmed by Sargent’s close friendship with Monet and by him showing A Morning Walk at the St Botolph Club’s winter exhibition in January 1890. Equally, paintings by Sargent that depicted the French artist at work such as Claude Monet Painting by the Edge of the Wood ?1885 (Tate N04103; fig.5) exhibited at Boston’s Copley Gallery in 1899, further reinforced his affiliation with Monet and impressionist circles in France.37

Moreover, the timing of Sargent’s reorientation towards American exhibition circles and galleries, and his ten-month visit to America from December 1889 until November 1890 could not have been more opportune since between 1889 and 1892 an ‘astounding number’ of paintings by Monet were exhibited in the United States. Bought by local New England collectors, many of these purchases were displayed at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston from 1891 and favourably reviewed.38 This growing interest in the French artist was launched by Monet’s first exhibition in the United States at the Union League Club in New York in February 1891 with many works lent by Durand-Ruel. This show was quickly followed by Durand-Ruel’s acclaimed March 1891 exhibition at the Eastman Chase Gallery in Boston of The Impressionists of Paris from the Galleries of Durand-Ruel Paris and New York where Monet’s paintings featured alongside canvasses by Camille Pissarro and Alfred Sisley. Furthermore, in February 1895 twenty seven of Monet’s canvasses were exhibited to critical acclaim at the St Botolph Club in Boston with the show being a reduced version of the French artist’s first retrospective held the previous month at Durand-Ruel’s Gallery in New York.39

Apart from capitalising upon American collectors’ and museum directors’ fascination with modern French art, Sargent’s family connections in America, and especially in New England, were invaluable in furnishing him with introductions to important collectors and facilitating portrait commissions.40 Sargent’s paintings also conspicuously aligned him with an increasingly visible Franco-American school of artists who had been trained in France, and who were now returning to the USA and painting American landscape subjects in an updated impressionistic manner. Sargent’s artist friends Dennis Miller and Frederic Porter Vinton were both keen advocates of the new style of painting American subjects in an appropriated impressionistic technique, but approached from a distinctly American perspective.41 Growing American support for cultural cosmopolitanism in art was signalled by the speed at which American collectors, galleries and museum collections bought modern French and French-inspired impressionist works by younger American artists.42 This success was highlighted by the ‘burgeoning demand for American art among museums, galleries and collectors in the 1890s’ and the style’s promotion at the 1893 Chicago Columbian Exposition when American critics enthusiastically heralded such work and its patronage as constituting ‘a new American School’ and demonstrating ‘feelings of an intense Americanism’ validating the nation’s cultural ambitions.43

Fig.6

John Singer Sargent

Mrs. Hugh Hammersley 1892

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

© Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Nevertheless, while visiting Boston and New York, Sargent also became aware of the growing demand for modern portraiture and witnessed the high prices that Europe-based artists could command by undertaking fashionable portraits of American sitters. It has been estimated that during his visit in 1889–90, he executed more than forty portraits with twenty-five of them commissioned.44 Building upon the later ‘cracking success’ of Mrs Hugh Hammersley 1892 (fig.6) and Mrs George Lewis 1892 included in the spring 1993 show at the New Gallery in London alongside Lady Agnew of Lochnaw 1892, exhibited at the Royal Academy in May 1893, Sargent was well placed to exploit the strong colonial heritage in the United States that looked to Britain as part of a shared Anglo-American culture and trans-Atlantic Anglophile kinship.45 As a consequence of Sargent’s growing success, English critics had revised their critical positions and while some like the critic and painter Roger Fry saw Sargent’s 1902 The Duchess of Portland’s ‘self-assertive bravura of pose’ as showing ‘the effrontery of the arriviste’,46 many now applauded Sargent’s portraits as ravishing ‘pieces of well-engineered impressionist painting [that] top everything in the Academy’.47 In particular, the Agnew portrait was seen as ‘not only a triumph of technique but the finest example of portraiture, in the literal sense of the word that has been seen here for a long time. While Mr Sargent has abandoned none of his subtlety, he has abandoned his mannerisms’.48 By the time of the series of Portrait Loan Exhibitions at the National Academy of Design in New York in 1894, 1895 and 1898, Sargent’s portraits’ style, with their Francophile manner and startling colour contrasts, was seen as a praiseworthy and innovative updating of the eighteenth-century British ‘grand manner’ portraiture of Thomas Gainsborough, Thomas Lawrence, George Romney and Joshua Reynolds, and for American critics, to have remarkable alliances with the work of the Boston artist John Singleton Copley.49 Indeed, from 1894 Sargent’s standing as a society portraitist on both sides of the Atlantic was firmly established and ‘he was the unchallenged leader among American portrait painters’.50

By 1900, in an ironic reversal of fortune, many English critics now interpreted Sargent’s remarkable standing as a fashionable portraitist as indebted to his cosmopolitan background arguing that the artist’s sense of detachment gave him a privileged and seemingly thoroughly modern insight into capturing the sitter’s ‘inner life’ and complex psychology. Moreover, as art historian Elizabeth Prettejohn has shown, by this date Sargent had become incorporated into a privileged circle of patrons and collectors; ‘the portraitist of choice … for the more artistically minded amongst the [British] aristocracy and nouveau-riche American plutocracy’.51 Demand soared as these portraits registered as the ‘ultra-modern’ updating of British grand manner portraiture involving the use of ‘advanced compositional techniques and broadly impressionistic brushwork’ and were applauded for their subtlety, depth and beauty.52 Between 1900 and 1907 Sargent’s international reach was at its peak as over 130 portraits were produced with thirty portraits being exhibited at the 1902 Royal Academy exhibition in London alone.53

However, the phenomenal rise of Sargent’s artistic output and the scale of these expansive trans-Atlantic operations opened Sargent’s creative aesthetic up to more conservative approaches to cultural cosmopolitanism that were gaining ground in Britain and which, in the United States, were being re-shaped according to shifting national social and political agendas. This re-evaluation of artistic and national identities in the arts was directed not least by the fact that the United States after 1898 was itself positioned as an imperial rival to Britain and France. Across the Atlantic, such an internationalist outlook in an American artist became increasingly suspect in the light of growing American political and imperial aspirations leading to a revisionism that heightened during Theodore Roosevelt’s presidency from 1901 and was fired by his 1904 extension of the Monroe Doctrine from a western hemisphere to global American ‘spheres of influence’ in foreign policy.54

Fig.7

John Singer Sargent

Mr and Mrs I.N. Phelps Stokes 1897

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

In particular, by operating between and across these dynamic transnational art economies and negotiating the very different segregated art markets, professional associations, exhibition networks and nationalistic art policies developing in London, Paris, Boston and New York, Sargent had to manoeuvre the intense and growing imperial rivalries that were emerging between Britain, France and the United States. The complexity of his situation in relation to this resurgence of imperial claims was highlighted at the international exhibitions in Paris in 1889 and 1900, and in Chicago in 1893, when anxieties about Sargent’s placing within different national submissions emerged most forcefully. Arguably, the most extreme divergence in English and American critics’ estimations of Sargent’s national affiliation surfaced at the 1900 Exposition Universelle in Paris, when American writers applauding Sargent’s participation in the American section had no difficulties in claiming him as one of theirs.55 As Diane P. Fischer has shown in her detailed study entitled Paris 1900. The ‘American School’ at the Universal Exposition (1999), the American Department of Fine Arts, supported by a well-funded, ambitious and politically motivated campaign, promoted ‘a new position for the United States as an art producing nation [free of] foreign trammels’.56 Sargent, situated alongside Whistler, was claimed as one of the chief founders and a major exponent of this new American school. Moreover, the sense of an integrated American school was achieved at the Paris Exposition by showing the work of expatriate Americans – so-called ‘Paris Americans’ – alongside US-resident artists in order ‘to create the illusion of solidarity in American art’.57

Fig.8

John Singer Sargent

Colonel Ian Hamilton, CB. DSO. 1898

Tate

© Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

In summary, as Sargent’s work traversed the Atlantic between London, Paris, Boston and New York, there were at least five major areas of conflict in the estimation of the perceived national identity and cultural affiliation of Sargent’s portraits and figure studies. The first dispute focused on the differing forms of English and American self-presentational models that critics perceived in the portraits. For example, between 1897 and 1901 Sargent had undertaken a number of ambitious portraits of rich American families, such as Henry G. Marchand 1897 (fig.4), Mrs Charles Thursby c.1898, and Mr and Mrs I.N. Phelps Stokes 1897 (fig.7).58 Art critics in the United States interpreted their confident presentational modes and Francophile painterly style as, at once, the marker of a sophisticated American cosmopolitanism that came from one of their own compatriots’ modern experience of living and working in Paris and London.59 At the Paris Exposition Universelle in the American Pavilion in 1900, Sargent had included his Portrait of Miss M. Carey Thomas, President of Bryn Mawr College 1899 showing the sitter dressed in black academic robes edged with dark blue velvet stripes and hood. The artist had adapted the distinctive forms of Anglo-English aristocratic presentational modes and grand manner art historical referencing, but in this case to represent a PhD-educated, independent, professional American ‘new woman’ who was a prominent suffragist and pioneer in women’s education. For English critics, this appropriation constituted yet another example of misplaced sophistication with the signs of aristocratic breeding ill-applied to a well-educated and overly confident American educationalist. The portrait’s American assurance was seen by English critics to embody a distinctive overly confident American manner of self-presentation, reflecting not an aristocratic lineage but a more plutocratic American society that was itself becoming a colonial power.60

A second area of anxiety emerged when Sargent’s portraits of well-bred members of the British aristocracy were exhibited in the United States. American critics, due to their unfamiliarity with the historical nuances in Anglophile class distinction and social manner in Britain, were unconvinced about the conviction of such portraits. Consequently, they often found the refined self-presentational models of the British aristocratic portraits as lacking in vivacity and forcefulness.61 For example, when the portrait of Colonel Ian Hamilton, CB, DSO 1898 (Tate N05246; fig.8) was shown at the New Gallery in London in 1899, the Art Journal critic applauded Sargent’s depiction of ‘the muscular jaw and throat’, and applauded the way ‘the chin shoots out in challenging disdain’ as being an appropriately impressive, manly pose for a leading British military figure.62 By contrast, when exhibited at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts in 1901, more than one American critic complained about the sitter’s lack of masculine authority, jibing that the portrait conveyed merely ‘the pathetic force of the gaunt, sickly subject’.63

Fig.9

John Singer Sargent

Asher Wertheimer 1898

Tate

© Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Fig.10

John Singer Sargent

Mrs Carl Meyer and her Children 1896

Tate

Fig.11

John Singer Sargent

Ena and Betty, Daughters of Asher and Mrs Wertheimer 1901

Tate

Thirdly, similar differences in approach surfaced when Sargent painted portraits of the plutocratic urban elites referencing aristocratic codings and using earlier Anglo-English grand manner styles of modelling. In particular, Sargent’s portraits of nouveau-riche Jewish patrons evoked differing responses as attitudes towards immigration and its benefits and questions of race, breeding and new money were evaluated differently on either side of the Atlantic.64 For example, Sargent’s portrait of the London art dealer Asher Wertheimer painted in 1898 (Tate N03705; fig.9) and Mrs Carl Meyer and her Children 1896 (Tate T12988; fig.10) were among a series of portraits of the wealthy and prominent Jewish family completed by Sargent between 1898 and 1906.65 As art historian Kathleen Adler has demonstrated, when exhibited in London their reception had been negatively framed by anti-Semitism arising from the social changes from land ownership taking place in Britain and the contentious practice of giving honorary titles to the industrial and corporate rich.66 These debates also openly exposed the conflicting attitudes among English upper and middle class audiences towards ‘Jewishness’.67 As a result, English critics felt that the portraits of Jewish sitters had a ‘lush quality [and] an immediacy and intimacy’ which commentators even recently have found ‘quite different from the reticent formality of the [Anglo] aristocratic or Colonial portraits’.68 Moreover, they condemned the paintings’ perceived ‘overt sensuousness, improper eroticism and excessive energy’ as highlighting not only Sargent’s, but also the sitters’, lack of understanding of English codes of restraint and decorum. Indeed, Sir Charles Oman castigated the portraits including Portrait of Ena and Betty, Daughters of Asher and Mrs Wertheimer 1901 (Tate N03708; fig.11) as ‘clever but repulsive pictures’ and the art critic of the Spectator saw the portraits as carrying the marker of ‘over-civilised Orientals’ as painted by unknowing foreigners.69 When they were donated by Asher Wertheimer to the Tate Gallery in 1923, similar reservation re-emerged about Sargent’s commercial motivations and his wish to fulfil the social ambitions of his sitters by portraying the rich and parvenu Jewish sitters in such a professionally skilled and masterful way by suggesting an assured historical pedigree for such newly affluent sitters.70

A fourth area of dispute focused on the differing estimations by critics on either side of the Atlantic of the value of and motivation for Sargent’s mural commissions in the United States. From 1895 until 1925 Sargent had been working on three monumental mural commissions for the Boston Public Library (1895–1919), the Widener Memorial Library at Harvard University (1921–2) and the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston (1918–25).71 Positioning himself within the influential and growing grand-scale mural movement gaining momentum in the United States, these commissions marked out Sargent’s commitment, alongside that of other American artists, to a distinctively American mural practice that was committed to a high-minded civic endeavour as a sign of the progress of American civilisation.72 The extraordinary popularity of Sargent’s elaborate mural paintings at the Boston Public Library and the Museum of Fine Arts in particular was seen by British critics as a sign of their lack of serious artistic merit and they were derided as populist and overly ‘decorative’. Fry argued that they were more like ‘literature’ than art, and that the complex symbolism of Sargent’s Museum of Fine Arts designs was lamentably ‘literal’, requiring ‘annotations’ for the contemporary viewer to make its aesthetic fully understood.73 Leading American art historian Bernard Berenson dismissed them outright as decidedly ‘lady-like’.74

Fig.12

John Singer Sargent

The Piazetta, Venice c. 1904

Tate

Fig.13

John Singer Sargent

Riva Degli Schiavoni, Venice c.1904

Tate

Lastly, there were contested views over the artistic worth of Sargent’s watercolour works, notably at the time of the Carfax & Co. Gallery exhibition in London in April 1905 when The Piazetta, Venice c.1904 (Tate N03408; fig.12) and Riva Degli Schiavoni, Venice c.1904 (Tate N03406; fig.13) were shown. This exhibition was followed by enormous exhibitions of watercolour works at Knoedler’s in New York in February 1907, when eighty-three watercolours were bought by the Brooklyn Museum and later, in March 1912, when forty-five watercolours were purchased by the Boston Museum of Fine Arts.75 These substantial sales of watercolour paintings to major American museums not only attracted large commercial success but gained for Sargent important American institutional recognition, which many English critics believed was unjustified. When displayed again at the Carfax & Co. Gallery in London in 1908, Sargent’s watercolours, although favourably reviewed, had attracted some sceptical responses. For the Evening Post critic, although Sargent’s skill was self-evident, its purpose was often unclear as ‘one cannot discover what he finds beautiful … Everything seems to be represented with an equal vividness and skilled indifference’.76 The Builder’s critic went even further condemning the watercolours as ‘too offhand and careless in manner’, more like ‘artist’s memoranda than pictures’.77 Seen as commercially motivated and ‘touristic’, the watercolours, some English critics argued, never delved below superficial appearances of the places visited and sights seen. As such, they failed to respect the cultural authority and technical sophistication required by the English watercolour tradition. For example, Roger Fry, reviewing Sargent’s watercolours, concluded that Sargent’s works offered no profound artistic insights:

What [Sargent] saw was exactly what the upper class tourist sees … As an illustrator, then, Sargent’s evaluation of phenomena is almost always that of the average cultured Anglo-Saxon … He reveals no vivid personal response; he is satisfied with what is immediately striking to all eyes [and] he has the undifferentiated eye of the ordinary man trained to its finest acuteness for observation and supplied with the most perfectly obedient and skilful hand … Sargent was striking and undistinguished as an illustrator and non-existent as an artist … his values are never aesthetic values.78

These conflicting estimations of Sargent’s work and its disputed cultural affiliations were repeated in many reviews, articles and studies published in the first two decades of the twentieth century when Sargent’s reputation as a fashionable portraitist, impressive muralist and accomplished watercolour painter was reinforced by his receipt of international honours and growing trans-Atlantic status. The rising demand and prices paid for his portrait paintings completed until 1907, when he largely stopped producing, was however seen by many English reviewers as evidence of Sargent’s commercial motivation. As art writers increasingly employed broadly based ‘national’ characteristics to evaluate artistic worth and designate allegiances, so Sargent’s Italian birthplace, American nationality, French training and British residency were differently accentuated and evaluated by British and American commentators. In spite of the artist’s technical brilliance, his sustained sales and the publication of many complimentary critical evaluations and memorial essays, both British and American art writers remained conflicted about the seemingly detached nature of Sargent’s cosmopolitan sensibility and they questioned any claimed positioning of his work within British and American national schools.79 As the Manchester Guardian art critic queried in May 1903, when reviewing the Carfax & Co. show in London, ‘Mr Sargent’s work is to most of us a puzzle. It is difficult quite to see where it stands in modern painting’.80

These anxieties resurfaced most prominently at the time of three extensive exhibitions organised after the artist’s death on 15 April 1925 and again at the opening of the Modern Foreign and Sargent Galleries at the Tate Gallery in June 1926. Faced with large scale exhibitions in Boston, New York and London, and Sargent’s placing within a gallery layout distinguishing between modern British and foreign schools of painting, critics on both sides of the Atlantic published posthumous reassessments of Sargent’s legacy. On 3 November 1925 the first memorial exhibition opened at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, followed the next year by one at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.81 These exhibitions in the United States sought to emphasise Sargent’s American credentials by reinforcing his ‘American blood’ and New England ancestry, and by searching for conspicuous signs of ‘American-ness’ in his art. In the foreword to the Boston catalogue J. Templeman Coolidge once again highlighted Sargent’s ‘degree of reticence and impersonality’ as a marker of a disengaged American expatriate experience and in the catalogue introduction to the Metropolitan Museum’s retrospective, Mariana van Rensselaer quoted the artist’s own words in support of its claim to Sargent as an American artist: ‘I have never considered anything but my American citizenship.’ Yet the fact remained that Sargent ‘had spent practically all his life in Europe’, and his works’ cosmopolitan alliances were recognised by van Rensselaer as undermining this American nationalist agenda since ‘Sargent the artist was not an American … his affiliations were with France’. He was ‘cosmopolitan for the France that taught him [and that] was teaching half of the world’.82 Other American critics recognised that claiming Sargent as a distinctively ‘American’ artist was fraught with difficulties considering his time lived abroad and his work’s lack of adherence to any national style arguing that it was ‘fortunate [for Sargent] to have lived in an age devoted to artists’ biography. Had he lived in an age willing to leave [artists] in anonymity his work might well have come to be set down merely as part of the diffusion of the French school’.83

In 1926 a third memorial exhibition opened at the Royal Academy in London, allowing English critics to re-evaluate posthumously Sargent’s reputation and assess his legacy as a Royal Academician.84 Clive Bell, reprinting an earlier estimation of Sargent’s art, noted that he was ‘a brilliant observer and a dextrous craftsman, but not a great artist’. Lamenting that he ‘could have been a Degas or a Lautrec’, Sargent’s works were seen to repeat well-worn formulae and as a result of his commercialism, he was ‘sold out by 30’.85 Raymond Mortimer in the New Statesman rounded that Sargent’s paintings were decidedly ‘un-modern’ and merely a ‘mirror reflection of the Edwardian bankruptcy of taste’.86 And in Fry’s review in the Nation and Athenaeum, published on 23 January 1926, the critic went even further, openly vilifying Sargent’s work as retrograde and condemning it as a weak and ‘feeble echo … of what Manet and his friends had been doing with a far different intensity for ten years or more’. Sargent’s art was dismissed by Fry as ‘an emasculated version’ of French painting marking out ‘a feeble search for aesthetic values’, but showing ‘no talent as a draughtsman’ and having ‘no visual passion’. Sargent, Fry concluded, ‘was striking and undistinguished as an illustrator and non-existent as an artist’.87

Fig.14

Sir John Lavery

King George V Accompanied by Queen Mary, at the Opening of the Modern Foreign and Sargent Galleries at the Tate Gallery, 26 June 1926 1926

Tate

Finally, these issues resurfaced forcefully at the sale of the contents of Sargent’s studio in London in July 1925 and at the opening of the Modern Foreign and Sargent Galleries at the Tate Gallery on 26 June 1926, depicted by Sir John Lavery in his painting King George V Accompanied by Queen Mary, at the Opening of the Modern Foreign and Sargent Galleries at the Tate Gallery, 26 June 1926 1926 (Tate T04906; fig.14).88 These events generated even more publicity about Sargent’s diverging reputation, further stoking Anglo-American rivalry about his legacy and where his work should be located within the development of modern art. At the Christie’s sale, English critics expressed surprise at the prices that Sargent’s works achieved, particularly when purchased by American buyers.89 At Millbank, the Sargent room was located next to a suite of galleries showing ‘recent … continental art’ by mainly French artists, notably Monet, clearly suggesting that it was among such ‘Modern Foreign’ art that Sargent’s work’s proper affiliations lay. And in these art galleries, funded to the tune of £30,000 by the art dealer Sir Joseph Duveen, who had recently and somewhat contentiously been knighted in 1919 and made an Associate of the National Gallery, there was the Sargent room where prominently displayed was Sargent’s Claude Monet Painting at the Edge of a Wood (fig.5) and the nine portraits of the nouveau-riche Jewish Wertheimer family (including figs.9, 10, 11) that had been bequeathed as a gift to the nation by Alfred Wertheimer in 1922; a donation framed according to shifting post-war attitudes to Jewishness and which ‘had given rise to a considerable amount of antagonistic feeling and criticism in certain artistic circles’.90 Writing in the New Statesman, Fry once again took the opportunity to criticise Sargent’s lack of artistry and questioned in an ironic tone the motivation for the donation: ‘Throwing over as irrelevant the purely aesthetic point of view, I can see and rejoice in Mr Sargent’s astonishing professional skill … I for one welcome the bequest by which the National Gallery becomes the trustee of Sir Asher Wertheimer’s fame’.91

To conclude, throughout his career Sargent’s figure paintings drew mixed and divergent critical responses when displayed in Britain or the United States. On the one hand, progressive and supportive English critics embraced the sophisticated cultural cosmopolitanism that they detected in his art. They admired Sargent’s swift technical assurance and the work’s clever impressionistic updating of eighteenth-century British portraiture allowing for a renewed and intense psychological enquiry. On the other hand, for his detractors, Sargent’s paintings were criticised for their French fashionability, passionless detachment, commercial appeal and intellectual vacuousness. Think of the British painter Edward Burne-Jones’s damning rebuke in 1896 when he declared that Sargent’s portraits with their impressionist technique and elevated colour palette were not at all to his taste: ‘The dabs are all that I hate in execution – and the colour is often hideous – & not one faintest glimmer of imagination has he’.92

At the time of the 1900 Paris Exposition Universelle, American critics and American patrons of French and American impressionism located Sargent’s work and its high prices as evidence of the emergence of an eclectic ‘American School’ of which Sargent, alongside Whistler, was a ‘founding father’. Yet in 1900 the British organising committee saw Sargent’s appropriation into the American section as a disrespectful disregard of his London residency and a blatant insult to his British collectors and patrons. For English critics, Sargent’s American allegiance, like the burgeoning demand from American buyers for his grand manner portraits, from American public patrons for elaborate mural programmes and from American public art museums for his watercolours, signalled how modern art was being used by the United States to validate its own cultural aspirations and to underpin its growing economic and imperial ambitions.

These differences in approach became particularly acute in the years 1908–10 when more markedly nationalist frameworks – voiced for instance in Brinton’s 1908 survey of Modern Artists and underpinning Rothenstein’s comments about Kessler – were employed that saw cosmopolitanism in modern art as suspect, dissipated and flawed: what artist Percy Wyndham Lewis castigated as that ‘cosmopolitan sentimentality’ which is a ‘feeble European’ marker of a ‘miserable intellectualism’ perniciously spreading abroad from Paris and its art schools.93 What a closer examination of the complex trans-Atlantic reception history and competing critical reactions to Sargent’s cosmopolitanism underscores is how, as modern art became subject to the expanding interpretational possibilities and competing critical frameworks powered by a rapidly expanding global art economy and a growing network of publishing syndicates, the work of a leading international portraitist, now consumed in ever more distant geographical contexts, and by a wider range of socially, ethnically and racially diverse audiences, accrued meanings and shades of interpretation according to shifting national political imperatives.

As a consequence, Sargent’s reputation was substantially recast in the decades of the 1910s and 1920s when his works’ perceptual naturalism and impressionistic handling was praised by his many American supporters as a distinctively American version of French impressionism. For them Sargent’s was a praiseworthy modern and sophisticated art of technical brilliance and artistic distinction. For his British detractors, notably art writers who adopted increasingly formalist approaches that underpinned later modernist epistemologies, Sargent’s fashionable portraits with their dazzling technique were suspect as superficial and compromised, market-driven virtuoso ‘performances’ with a dubious ‘foreign’-inspired aesthetic quality that was castigated as illustrative and unconvincing. Moreover, the high prices paid for his commissioned society portraits of wealthy American and Jewish nouveau-riche sitters and by American museums for his watercolours, and the popularity of his elaborate mural programmes for the Boston Public Library and the Museum of Fine Arts damned Sargent’s style as too commercially-orientated. Indeed, what my article has revealed is that, when seen within a trans-Atlantic interpretive frame, the complications and contradictions attendant upon evaluating cosmopolitanism when perceived as part of Sargent’s national identity, or detected by critics in the artist’s coldly selective and detached approach, were themselves signs of the accelerating pace of change and major structural changes taking place in the trans-Atlantic art economy framed according to the shifting Anglo-American geo-politics between c.1886 and 1926.