The use of pop-derived graphics in the iconic posters of the Atelier Populaire to protest American-style capitalism and imperialism remains a salient, if under-examined paradox of the events of May 1968 in France. In 1960s France, American pop art was largely perceived to be an infantile neo-dada provocation, an attack on painterly technique via mass media images and the ideological agent of a foreign consumer society. Although some French critics were sympathetic, consternation over pop art’s mechanisation of painterly technique largely obscured the political relevance of its popular imagery and challenge to aesthetic hierarchies.1 Nevertheless, many of the artists and students who established the Atelier Populaire in the occupied lithography studios of the École des beaux-arts resorted to pop pictorial techniques such as the silkscreen and the opaque projector to incorporate photographic images in a moment of political crisis, building a critique of the mass media into images of political revolt. The use of these devices to reproduce photographic images in some of the most iconic posters from the events engendered debates within the workshop that pitted manual against mechanical representation, and collective practice against specialised tools and skills. Discussions over the production and content of the posters derived from recent artistic debates over pop art and the parameters of modern realism, revealing the political limitations of traditional artistic formats such as easel painting in the era of mass media. In some Atelier Populaire posters the high-low dialectic of pop art was inverted and painting became a symbolic and technical resource for political poster design. Examining the adaptation of pop forms in the Atelier Populaire highlights processes of transatlantic cultural transfer as well as the politicisation of art during the events of May 1968.2

The posters of the Atelier Populaire have been discussed in the context of art history, graphic design and cultural and political history. They have been compared with French lithographic posters of the nineteenth century, the posters of the Cuban Revolution, Soviet Rosta windows and the dazibao of the Chinese Cultural Revolution.3 While some scholars have noted similarities between pop silkscreen graphics and those of the Atelier Populaire, the specifics of this relationship have been obscured by the apparent contradictions of associating an anti-capitalist critique with pop art’s celebration of consumerist superficiality. Another important factor in the obscuring of the relationship between pop and the posters was the anonymity pact between participants, which suppressed the debates and circumstances of production in the workshops.4 However, since it has come to light that those working at the Atelier were also painters associated with groups such as the Salon de la Jeune Peinture and Figuration Narrative, aesthetic debates surrounding political engagement, the use of found imagery and mechanical painting techniques have come into focus as important ways of analysing the design and production of the May 1968 posters.

Histories of May 1968 have juxtaposed the cultural and political implications of the events. Many have viewed the student protests as a cultural rebellion focused on freedom of expression, sexual liberation, and autonomy from Gaullist technocracy and social norms. Given the failure to immediately topple the government of Charles de Gaulle and overturn the social order, these scholars construe the events as a youth ‘psychodrama’ brought on by sexual repression and the cultural backwardness of the Fifth Republic.5 However, others have argued that the political significance of the events lies in the alliances forged between protesting students and striking workers, the momentary supersession of these identities and societal roles, and the alignment of desires for cultural and political change.6 From this perspective the graffiti, political cartoons, protest chants and posters are poignant demonstrations of the extent to which cultural expression responded to and was transformed by political exigency. Art filled the void left by official culture and mass media during the strikes by occupying the empty channels of communication and mimicking them in form if not in content. According to cultural historian Kristin Ross, the speed of the unfolding events challenged artists and sidelined traditional beaux-arts mediums:

May ‘68 itself was not an artistic moment. It was an event that transpired amid very few images; French television, after all, was on strike. Drawings, political cartoons – by Siné, Willem, Cabu, and others – proliferated; photographs were taken. Only the most ‘immediate’ of artistic techniques, it seems, could keep up with the speed of events. But to say this is already to point out how much politics was exerting a magnetic pull on culture, yanking it out of its specific and specialized realm.7

Ross’s account is extremely useful for understanding the spatiotemporal demands placed on the artwork during the events. However, her suggestion that there was a concomitant turn away from specialised knowledge risks neglecting the technical and symbolic competencies that were brought to bear in the Atelier Populaire and affiliated workshops. The aim of this paper is not to assert a comprehensive re-reading of these posters as artworks rather than political ephemera, but to track the intersection of art and politics differently, in relation to pop. In turn this suggests a new understanding of the political adaptation of pop motifs in line with Lawrence Alloway’s comment that pop art was ‘de-aestheticized and re-anthropologized’ in commercial and popular culture of the later 1960s.8 That is, although the pop art of the early 1960s appropriated ‘low’ sources to forge a new form of gallery art, by the later 1960s mass culture began to use pop art motifs, reversing the direction of transmission and creating a feedback loop that artists continue to immerse themselves in today.9 In the non-elite and anti-capitalist mobilisations of the Atelier Populaire, pop and popular art converged to challenge both aesthetic and social hierarchies.10

Statistics on the post-war explosion in the French student population stand out in the vast literature on the ‘causes’ of May 1968 as indicators of looming crisis: the post-war baby boom and urbanisation caused the number of university students to rise from 123,313 in 1946 to 596,141 in 1971, a development that was met with an inadequate compensation in resources from the French government.11 For students, the lifeless concrete Nanterre campus built in 1964 in response to overcrowding at the Sorbonne had come to symbolise the failures of the French education system, bureaucratic sclerosis and the imposition of values from a bygone era. On 22 March 1968 a group led by Daniel Cohn-Bendit, a charismatic student of German-Jewish descent, transformed a sit-in protest about curfews and co-ed dorm visitation policies at Nanterre into a challenge to De Gaulle and Gaullism. The stakes were raised by the brutal response of the CRS arm (Compagnies Républicaines de Sécurité) of the Police Nationale who violently suppressed the protests at Nanterre with tear gas and mattraques (night-sticks), resulting in the arrest of over 600 students. The Nanterre campus was closed on Thursday 2 May and the unrest spread to the Sorbonne where another disproportionate police response escalated the conflict and led to the school’s forced closure for only the second time in its 700-year history. Incitement in the Latin Quarter culminated a few days later with ‘The Night of the Barricades’ on 10 May, when 30,000 protestors blocked Boulevard Saint-Michel and the police sealed exits along the bridges and main thoroughfares. In the ensuing exchange of tear gas, paving stones, mattraques and Molotov cocktails local residents acted in solidarity with protestors by sheltering them in their homes. The night was covered on radio and television including Radio Europe 1 – the only station not controlled by De Gaulle and the only broadcaster to rally public sentiment to the student cause. On Monday 13 May students occupied the Sorbonne and established the environment of liberated speech and debate that would become a defining characteristic of the events. The same day France’s two largest trade unions went on strike, participating in a march of over one million from Place de la République to Place Denfert-Rochereau that called for de Gaulle’s resignation and was at that time the largest protest in French history. Although the trade unions had planned for a one-day demonstration, the workers continued their strike into the week and wildcat strikes spread throughout factories and the public sector until Monday 20 May when ten million went on strike and France had ground to a halt. On 14 May students and artists occupied the lithography studios of the École des beaux-arts, which had been on strike since 8 May, with the intention of creating prints in support of the revolution.12

Fig.1

Usines, Universités, Union (Factories, Universities, Union) 1968

Lithographic poster

Considering the scale and violence of these events, the symbolic resonance of the ephemeral Atelier Populaire posters is all the more striking. Usines, Universités, Union (Factories, Universities, Union) (fig.1), the first lithographic poster produced in a print run of thirty, signalled the unity between workers and students and its claim for solidarity. The boldface U’s at the left side of the poster are uniform in scale, while the remaining letters of the three words take different fonts. The cursive script in ‘Universités’ suggests a blackboard scrawl and is distinct from the smaller print of ‘Usines’ and the larger block lettering of ‘Union’. The prints were intended for sale in nearby galleries and the proceeds were meant to support striking students and workers. However, amid the chaos of the events the demands of the street overtook those of the gallery: as artist Gérard Fromanger recounted, ‘the idea was to bring [the posters] to a supporting gallery for sale. But we didn’t make it ten metres in the street before the students snatched them and pasted them in the street themselves. We understood immediately: there was the idea! We went quickly back upstairs.’13

As the workshop gained momentum it began to draw participants from across the spectrum of Left parties and groups, ranging from the French Communist Party to Maoists, Situationists and Énragés. Striking workers, students, artists, intellectuals and hangers-on contributed to a festive atmosphere driven alternately by Rolling Stones records or North Vietnamese revolutionary chants. As Fromanger remembered: ‘we were the only ones who were working. It was very gratifying: the whole country was on strike except for us! We had never worked so hard in our lives!’14 Indeed, some devoted students and artists slept and ate in the studios. The workshops were run by general assemblies, which enforced collectivity and anonymity to keep police scrutiny at bay. Each night poster designs were submitted anonymously for debate and were voted on according to the questions ‘Is the political message correct?’ and ‘Does the poster transmit this idea well?’15 The debates ranged in duration from ten minutes to several hours, with some extending through the night. As the strikes spread, this model was replicated and poster ateliers were established in the École des arts décoratifs and in some occupied factories.16

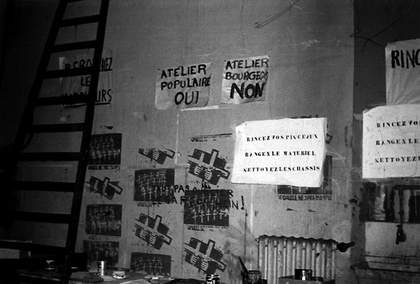

Fig.2

École des beaux-arts: ‘Atelier Populaire Oui!’

Photograph

Courtesy Bibliothèque nationale de France

Two hand-written signs tacked to the workshop wall (fig.2) announced the opposition between popular and bourgeois art that guided design and production in the studios: ‘Atelier Popuaire Oui’ and ‘Atelier Bourgeois Non’. With its refusal of bourgeois social norms and its invocation of the popular, this slogan juxtaposed the productive collective against the creative individual, declared the non-elite audience for the posters, and established the studio as a non-hierarchical space. The opposition of popular and bourgeois art was developed further in a statement ratified on 16 May and dispersed in tracts on 21 May, which targeted predominant notions of bourgeois art. The authors wrote ‘privilege confines the artist to an invisible prison’, isolating them with notions of ‘creative freedom’ and artistic autonomy. By elevating artists above workers, the authors continued, the bourgeoisie and the Ministry of Culture promoted the myth that:

(1) [the Artist] does what he wants to do, he believes that everything is possible, he is accountable only to himself or to Art.

(2) He is a ‘Creator’ which means that out of all things he invents something that is unique, whose value will be permanent and beyond historical reality. He is not a worker at grips with historical reality. The idea of creation de-realises his work [irréalise son travail].17

For the authors of the manifesto a meaningful relationship with historical reality was to be forged not through the use of modern techniques, but through an engagement with the problems facing the working class:

We want to be clear that it is not a better relationship between artists and modern techniques that will better align them with all other categories of workers, but an opening to the problems of the workers – to the historical reality of the world in which we live.18

Although the statement’s workerist position was intended to influence the direction of the poster workshop, the language echoed that of a manifesto written three years earlier by Gilles Aillaud, Eduardo Arroyo and Antonio Recalcati. The three painters formed the organising committee of the Salon de la Jeune Peinture – one of Paris’s annual painting salons that was also a politicised painting collective. From its inception in 1953 the Salon was loosely associated with the French Communist Party and it promoted figurative painting as an antidote to the formalism of art informel, which was otherwise dominant in the French avant-garde. In 1965 Aillaud, Arroyo, Recalcati and others assumed control of the organising committee of the Salon and brought its political undercurrents to the surface, taking aim at beaux-arts conventions and the privileging of individual expression over political engagement.19 The Salon sought to challenge what they viewed as the aestheticism of the neo-avant-garde and they stated their objective to ‘move the debate from the realm of aesthetics – the realm of the relations between art and the history of art – to the realm which interests us, that of the relations between art and history’. The central question for artists, the committee wrote, was ‘in what measure, however small, can painting participate in the historical revelation of truth?’20

Fig.3

Gilles Aillaud, Eduardo Arroyo and Antonio Recalcati

Vivre et laisser mourir ou la fin tragique de Marcel Duchamp 1965

© Musee National Centro de Arte Reina Sofia, Madrid

Aillaud, Arroyo and Recalcati exhibited a painting at the Galerie Creuze in 1965 which spelt out their rejection of the neo-avant-garde legacy in no uncertain terms. With a title taken from a 1954 Ian Fleming James Bond novel, Vivre et laisser mourir ou la fin tragique de Marcel Duchamp (Live and Let Die, or, The Tragic End of Marcel Duchamp) (fig.3) was a campy suite of eight paintings that showed the artists attacking, murdering and throwing the older French artist Marcel Duchamp down a flight of stairs. For Aillaud, Arroyo and Recalcati, Duchamp and the readymade represented the epitome of privileged aestheticism, giving the artist the agency to choose what might constitute art simply through the act of naming it as such. In precise renderings that verge on Oedipal undoing, Aillaud, Arroyo and Recalcati restored functionality to the objects that Duchamp had claimed for his art: Fresh Widow 1920 (see Tate T07282) becomes the blacked out window in a room where the artist is being interrogated, Fountain 1917 (see Tate T07573) is remounted to the bathroom wall and The Large Glass 1915–23 (see Tate T02011) provides a vantage onto an outdoor courtyard space that reasserts the picture plane as Albertian window onto the world. The penultimate panel shows Duchamp’s nude, emasculated body thrown down a staircase, a pendant piece to his Nude Descending a Staircase No.2 1912 (Philadelphia Museum of Art) represented in the first panel. In the final scene the artist is finally brought to his grave in a casket draped in an American flag and carried by likenesses of the artists and Duchampian heirs Robert Rauschenberg, Claes Oldenburg, Andy Warhol, Martial Raysse, Arman as well as critic Pierre Restany, each dressed in military uniform.21 In this last panel with its incongruous and disjunctively rendered visages, American pop artists and French nouveaux réalistes are cast as neo-avant-garde imperialists. In this case, and in contrast to the Salon’s interests in engaging a working class audience for art, pop stood for the retrenchment of art as elitist.

In a manifesto written to accompany the painting, Aillaud, Arroyo and Recalcati described their opposition to ‘la technique picturale et la personnalité technique’ (pictorial technique and the technical personality):

If one wants art to cease being individual, better to work without signing than to sign without working … [Duchamp’s] power over things is such that he doesn’t even touch them; by the pure decree of his choice he sticks a bicycle wheel on a pedestal and has it enter just as it is into the temple, i.e. the museum.22

The group elaborated in a subsequent text:

Marcel Duchamp’s abrupt rupture with oil painting does not, in effect, bring any change of perspective. From the cubist object, entirely constructed by the constituting action of the painter, to the manufactured object that has only been touched from a distance as by a signature, there is no supersession of the traditional and demiurgic notion of the ‘creative act’.23

The manifesto of the Atelier Populaire clearly reprised the Salon de la Jeune Peinture’s denunciations of aesthetic autonomy and bourgeois creativity and indeed Gilles Aillaud was the principle author of both texts. However, the transposition of the Salon’s theory of political engagement onto a collectivised poster workshop operating amid a political crisis was fraught with a rhetorical and pragmatic challenge. Although the poster workshop appeared to politicise art, the ideas articulated in the Jeune Peinture statements could no longer be presented as an ethic of painting. Jeune Peinture’s critique of bourgeois individualism was echoed in the Atelier Populaire’s collectivism, but the scale and drama of the protests laid bare the spatiotemporal constraints of handmade paintings such as Vivre et laisser mourir ou la fin tragique de Marcel Duchamp when faced with the speed of events unfolding in the street. In order to keep apace and to print in volume, the Atelier Populaire had to adopt one of the neo-avant-garde ‘modern techniques’ – silkscreen printing – alluded to in their manifesto. It was a way of working which brought them closer to pop art, graphic design and transatlantic cultural transfer, all of which they had criticised.

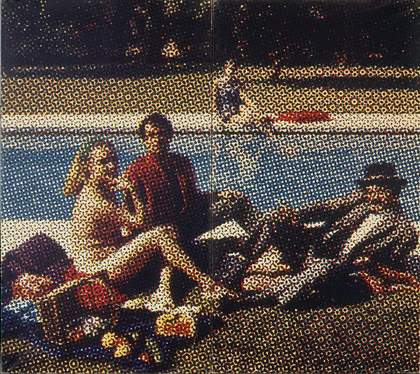

Fig.4

Alain Jacquet

Déjeuner sur l'herbe 1964

© Jacques Faujour – Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI /Dist. RMN-GP © Adagp, Paris

Fig.5

Martial Raysse

Made in Japan: tableau turc et invraisemblable 1965

Scholars have described the use of the silkscreen at the Atelier Populaire during May 1968 as an anomaly, because the technique was little used by artists and was not taught at the École des beaux-arts.24 Nonetheless the silkscreen was not foreign to France, as the American military had introduced it as a tool to make signs and label equipment after liberation from German occupation. Although it was not associated with fine art, the silkscreen did find artistic applications during the 1950s. Art historian Victoria H.F. Scott has noted that Fernand Léger made pioneering use of the silkscreen in France in his illustrations of Paul Eluard’s incantatory anti-occupation poem Liberté in 1952.25 Beginning in 1964 Alain Jacquet and other artists associated with the Mechanical Art or Mec’art group also used the silkscreen to create pop-inflected representations of works such as Edouard Manet’s Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe (fig.4). Instead of incorporating mass media images, Jacquet used the silkscreen to retool canonical works from the French avant-garde tradition, modernising their form if not their content. Martial Raysse similarly used enlarged photographic reproductions of Old Master paintings in his Made in Japan series. However, in works such as Made in Japan: tableau turc et invraisemblable (Made in Japan: Unlikely Turkish Painting) (fig.5) Raysse’s source images were not incorporated wholesale, but excerpted and collaged to make a new composition. Although his work from the 1960s is often associated with pop art, Raysse’s work was motivated by an exploration of the ways in which reproduced images affected the perception of both canonical Old Master and modernist painting.26 For Pierre Restany – a critical proponent of Mec’art – and others, their approach to silkscreen and photomechanical reproduction was distant from American pop. Restany wrote ‘as opposed to their American colleagues the Mec artists do not try to obtain a flat ready-made, but rather try to act on the organic structure of imagination’.27

Despite these precedents it was Guy de Rougemont, an abstract painter and sculptor who had recently returned from an extended trip to New York, who introduced the technique of silkscreen printing to the Atelier Populaire. Rougemont studied at the École des arts décoratifs in Paris from 1954 to 1958, fought in the French-Algerian War, and then travelled to New York in 1965, where his planned week-long visit became an eighteen-month stay. In New York his work was influenced by both pop art and minimalism and he befriended American artists including Marisol, Frank Stella, Robert Indiana, Larry Poons, Rauschenberg and Warhol.28 Rougemont’s subsequent work sought to overcome the divisions between fine and decorative arts and the boundaries between mediums imposed by the beaux-arts system by merging painting, sculpture and decorative arts in abstract spatial arrangements.29 Rougemont was drawn to the occupied École des beaux-arts for this reason, and out of a desire to ‘settle his account’ with the French government following his traumatic experiences during the French-Algerian War.30 Having recently completed a series of large prints for an exhibition in Japan with one of the only commercial silkscreen printing shops in Paris, Paris-Arts in the fifth arrondissement, Rougemont knew that the technique was better suited to the needs of the group assembled in the occupied lithography studios. He was asked to organise a silkscreen workshop and he fortuitously found Éric Seydoux – an apprentice at Paris-Arts who agreed to lend his skills and to help procure materials. Seydoux had also encountered silkscreen printing in the context of American art: he had studied at the Art Students League in New York between 1963 and 1967 and returned to Paris to pursue professional silkscreen printing because he considered it to be the technique that was ‘the most youthful, the most modern, the most promising’.31 Seydoux remembered that he and Rougemont demonstrated the silkscreen technique in the occupied lithography studio, creating a raised fist as their first design: ‘at that time the posters were printed using lithography, at very slow speeds. Nobody knew the silkscreen technique. With Guy’s materials, that night we printed the first poster in front of a transfixed audience and at great speed’.32 Compared with lithography or offset printing, the silkscreen was rudimentary, fast and industrious. Fromanger remembered:

Rougemont was there, who had just returned from New York and knew the silkscreen technique, along with a young printer, Éric Seydoux, who brought the first silkscreen to the Atelier Populaire and started to make prints. There were 200 people watching including 15 to 20 painters, and we found it to be magic, a miracle. We understood that we didn’t need the offset machine.33

In order to facilitate the creation of poster workshops in occupied factories and in the provinces, the Atelier Populaire distributed a text that detailed the steps of the silkscreen printing process. These instructions figure prominently among the founding documents of the Atelier Populaire, indicating the centrality of the silkscreen to the function and identity of the poster workshop. Far from a neutral medium, the industriousness of the silkscreen enabled the conceptualisation of the studio as a factory, and of posters as a form of counter-media able to respond to and shape the events.34

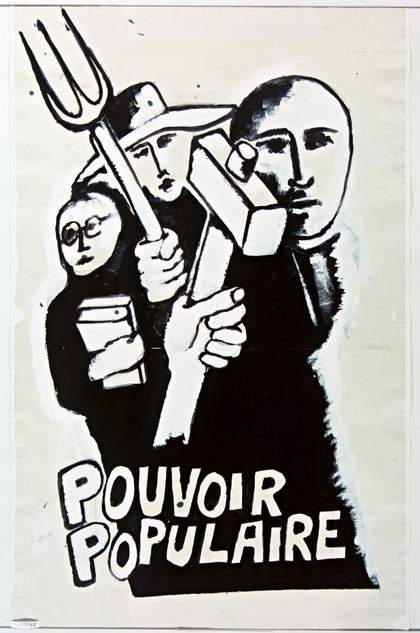

Fig.6

Pouvoir populaire 1968

Silkscreen poster

© Bibliothèque nationale de France

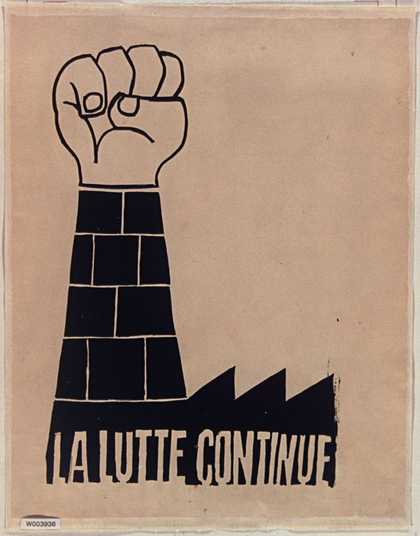

Fig.7

La Lutte continue 1968

Silkscreen poster

© Bibliothèque nationale de France

Although the posters that emerged from the Atelier Populaire and the other workshops are diverse in conception, design and execution, the motif of the hand and machine in opposition reappeared. This trope expressed the plight of factory workers while also conveying the tensions between artisanal and mechanical representation put forth by Jeune Peinture. While the lithographic poster Usines, Universités, Union called for solidarity between workers and students while maintaining the distinctions between them, subsequent silkscreen designs fused these identities with the depiction of hands and clenched fists as symbols of empowerment. In Pouvoir populaire (fig.6) a student, farmer and factory worker, shown holding a book, fork and hammer respectively, appear to share a single body. Another poster, La Lutte continue (fig.7) turns the iconic saw-toothed factory roofline and smokestack into a bicep, forearm and clenched fist raised in solidarity. The emphasis on manual labour in Pouvoir populaire and the anthropomorphism of La Lutte continue convey the tension seen in many posters between the mechanical and artisanal aspects of their production: although the Atelier was conceived as a factory and the posters were produced in a process akin to an assembly line, the designs retained a crude, tactile quality that highlighted ephemerality and material vulnerability in the street. Furthermore, the emphasis on handwork supported a representation of labour that, as other observers have noted, seemed to evoke the Popular Front of 1936 more than the occupations of technologically advanced Renault factories at Cléon, Flins or Boulogne-Billancourt.35

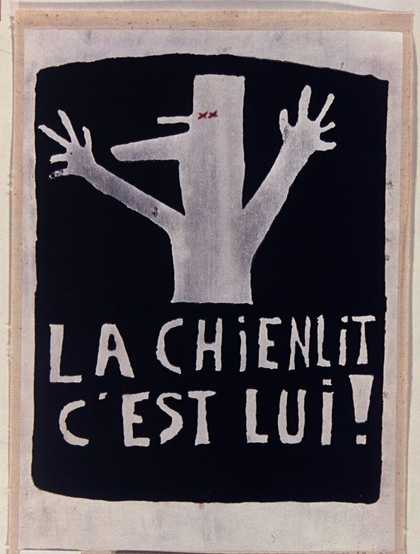

Fig.8

La Chienlit, c'est lui! 1968

Silkscreen poster

© Bibliothèque nationale de France

The speed and responsiveness of the silkscreen was reflected in one of the foundational posters of the Atelier Populaire, La Chienlit, c’est lui! (fig.8). The poster appropriated a remark de Gaulle uttered upon returning from a state visit to Romania as the strikes were escalating around 14–18 May. De Gaulle’s comment, ‘reform, yes, this chaos no!’ – which used the Rabelais-era, vernacular phrase chienlit that literally translates as ‘shit-in-bed’ – was repeated on the radio by the information minister George Gorse on 19 May. Gorse’s statement, a slur meant to describe the protesters as lazy, drew a response from the Atelier Populaire the same day, whose poster identified de Gaulle, depicted in rough silhouette, as the chienlit.

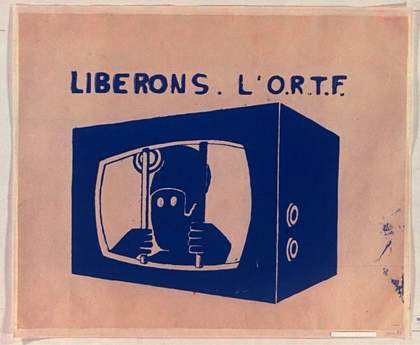

Fig.9

Libérons l'O.R.T.F 1968

Silkscreen poster

© Bibliothèque nationale de France

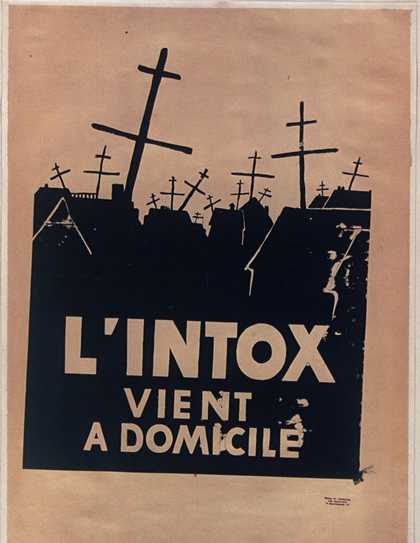

Fig.10

L'Intox vient à domicile 1968

Silkscreen poster

© Bibliothèque nationale de France

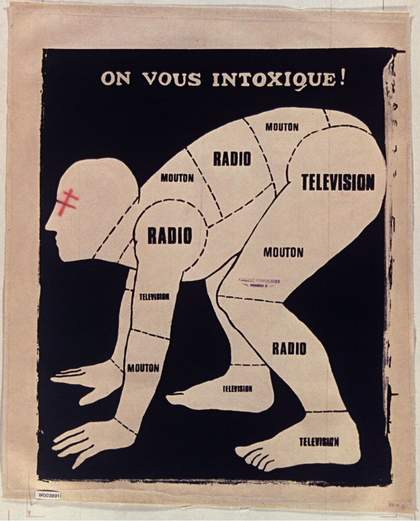

State control of the media soon became an explicit subject matter of the posters. When the television workers at the ORTF (the national media corporation) went on strike on 20 May, the Atelier Populaire produced a series of designs that juxtaposed the television and the poster as tools of oppression and emancipation. In Libérons l’O.R.T.F. (Let’s Liberate the O.R.T.F.) (fig.9), the mediations of television and poster screen are suggested by their superimposition in the poster graphic, which depicts a jailed revolutionary complete with Phrygian cap – the hat worn by freed slaves in ancient Rome and adopted by sans-culottes during the 1789 Revolution. In L’Intox vient à domicile (Propaganda Strikes Home) (fig.10), the double-barred Cross Lorraine – a symbol of the Resistance and of de Gaulle – becomes a television antenna and instrument of propaganda. On vous intoxique! (You Are Being Poisoned!) (fig.11) shows a butcher’s diagram dividing a prostrate human body into radio, television and mutton, with the Cross Lorraine serving as eyes. The poster plays on the stock comic-book trope of drunkenness, leveraging the double meaning of ‘intox’ as propaganda and intoxication.

Fig.11

On vous intoxique! 1968

Silkscreen poster

© Bibliothèque nationale de France

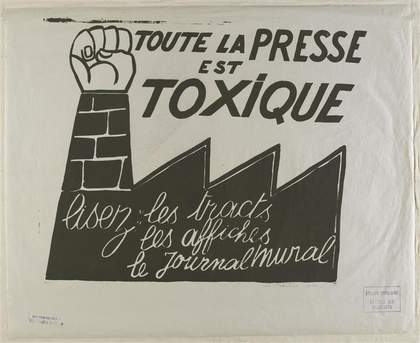

Fig.12

Toute la presse est toxique, lisez les tracts, les affiches, le journal mural 1968

Silkscreen poster

© Musée des Civilisations de l'Europe et de la Méditerranée

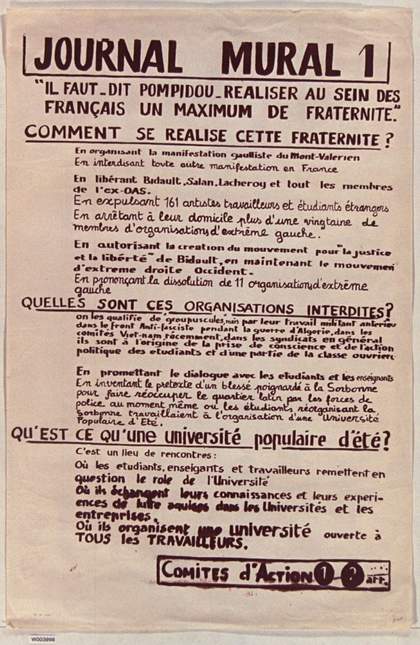

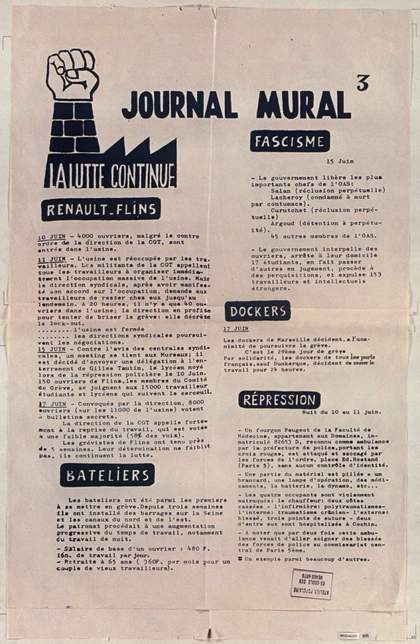

As the strikes entered their third week and the international press began to lose sympathy for the protestors, the posters increasingly became news outlets in their own right. Faced with a state-controlled ORTF, hostile foreign radio broadcasts and fatigue among the general public, the poster workshops produced their own narratives: ‘Toute la presse est toxique’ (All the press is toxic), announced a poster from early June, ‘lisez les tracts, les affiches, le journal mural’ (read our statements, our posters and the Journal Mural) (fig.12). The Journal Mural, produced between 13–21 June (figs.13–14), was an alternative publication produced by the Atelier Populaire to be pasted on walls as well as circulated. In this way the posters, which had been printed for convenience on newspaper provided by striking workers, shifted in form and content in relation to materials. The first issue responded to Prime Minister Georges Pompidou’s call for fraternity among citizens with an account of police attacks on students and a call for the formation of a ‘université populaire d’été’ (popular summer university) in the park. The third issue detailed the conflict between the striking workers at Renault and their union over the occupation of the factory, as well as instances of worker-student solidarity such as the funeral of Gilles Tautin – a high school student who drowned in the Seine while fleeing a police charge near the Renault factory at Meulan. These wall-newspapers juxtaposed second-hand reports in the official media with the immediacy of the street and first-hand observation of events, effectively ‘mediatising’ the walls of the Latin Quarter, as philosopher Jean Baudrillard later argued.36

Fig.13

Journal Mural 1 1968

© Bibliothèque nationale de France

Fig.14

Journal Mural 3 1968

© Bibliothèque nationale de France

Despite the silkscreen processes and engagement with print media in the posters considered so far, it is the photographic posters that bear the closest relationship to pop art. In these photographic posters pop art’s collapsing of manual and mechanical representation – the cause of such consternation to the Salon de la Jeune Peinture – enabled a synthesis of the counter-media function of the Journal Mural with iconic representations of solidarity such as Pouvoir populaire. By diverging from Jeune Peinture’s conception of realism as an engagement with the proletariat as the subject of history via the manual labour of representation, these posters propagated a photographic realism that depended on the mass media representations of events.

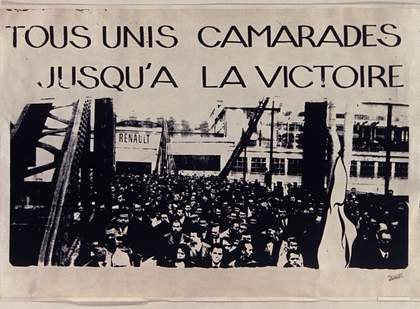

Fig.15

Tous unis camarades jusqu’à la victoire 1968

Photographic poster

© Bibliothèque nationale de France

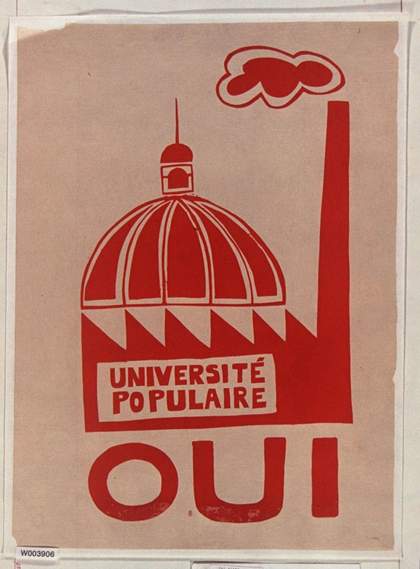

The photographic posters of the Atelier Populaire were produced with the photo-silkscreen or an opaque projector. The photo-silkscreen entailed the direct exposure of the silkscreen by the photographic source image, while the opaque projector involved manually tracing a projected photograph on paper and then transferring it onto the silkscreen template. In early June, Éric Seydoux and artist Éric Beynon procured the emulsion and equipment necessary for the production of photo-silkscreens. In their first efforts they used a glass passageway at the École des beaux-arts to expose photosensitised screens with images of striking workers.37 In Tous unis camarades jusqu’à la victoire (All Comrades United Until Victory), a courtyard of striking workers at the Renault Billancourt factory is shown in an accurate rendition of their workplace (fig.15). Sufficient detail is provided to distinguish labourers from suited professionals and to reproduce the Renault lettering on the factory, yet they are also abstracted enough to suggest the unity declared in the title. Such posters featuring photographic details of modern factories contrasted with the atavistic representations of saw-tooth rooflines and smokestacks in posters promoting worker-student solidarity such as Université populaire OUI (fig.16); the use of photographic source images lent posters such as Tous unis camarades jusqu’à la victoire an actuality that corresponding artisanal designs sometimes lacked.

Fig.16

Université populaire oui 1968

Silkscreen poster

© Bibliothèque nationale de France

Fig.17

Roy Lichtenstein (1923–1997)

Look Mickey 1961

National Gallery of Art, Washington

© Estate of Roy Lichtenstein/DACS 2012

There were, however, photographic posters produced before the arrival of the photo-silkscreen at the École des beaux-arts. These were made by manually tracing the outlines of photographic images projected onto paper using an opaque projector, and transferring the resulting design onto silk. In the United States the opaque projector was associated with Roy Lichtenstein’s subtly altered comic book frames and the somewhat paradoxical ‘handmade readymade’ images that resulted (fig.17).38 The device was introduced to French artists in 1964 when the art dealer Ileana Sonnabend procured an opaque projector for the French artist Daniel Pommereulle, who then introduced it to artists associated with Figuration Narrative such as Hervé Télémaque and Bernard Rancillac.39 The mechanical incorporation of found images via the opaque projector accelerated these artists’ engagement with highly publicised and politically charged subjects such as protests against the Vietnam War in the years leading up to May 1968. Indeed, Rancillac’s use of the opaque projector to develop a photo-based realist painting style had a strong impact on the Atelier Populaire posters that he designed using the same device.

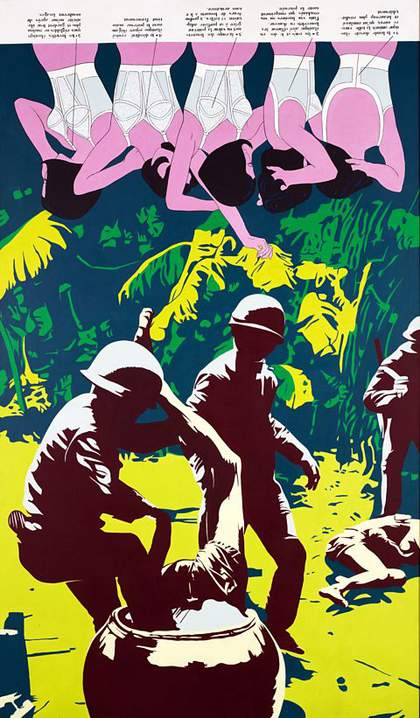

Fig.18

Bernard Rancillac

Enfin silhouettes affinées jusqu'à la taille 1966

Musée de Grenoble. Purchased from the artist in 1980 © Bernard Rancillac/DACS 2015

Late in 1965 Rancillac began using the opaque projector to combine found images in acrylic paint to forge a method that he termed ‘dialectical realism’. His exhibition L’année 1966 held at the Galerie Blumenthal-Mommaton in February 1967 featured paintings made over the previous year that used the opaque projector and masking tape to abstract and remix mass media images into politically charged compositions. Enfin silhouettes affinées jusqu’à la taille (At Last, a Silhouette Slimmed to the Waist) (fig.18) juxtaposes an image from Paris Match of South Vietnamese soldiers drowning a Viet Cong prisoner to the waist and an advertisement for women’s underwear that defined the waist. As the images occupy opposite ends of the canvas they are brought into an unusual proximity, demanding that the viewer confront the contradictions of the modern industrial world. Rancillac explained the dialectical realism of the painting: ‘the viewer is forced to choose a visual and hence political orientation. Comfort here, torture over there’.40 Art historian Sarah Wilson has argued that in these works Rancillac imitated the graphic effect of silkscreen printing in order to convey his contemporaneity while staying within the limits of hand painting. She has written: ‘the imitation of a silk-screened effect through the use of masking [tape] offered technical equivalents for his uncompromising stance, his sense of urgency’.41

Rancillac’s synthesis of painting and photography was the subject of sociologist Pierre Bourdieu’s catalogue essay, titled ‘L’image de l’image’, for the exhibition at Blumenthal-Mommaton. Bourdieu argued, echoing Roland Barthes’s skepticism of the photographic ‘reality effect’, that Rancillac’s painting subverted the deracination and passive consumption of photographic images in newspapers and photographic weeklies.42 Bourdieu wrote: ‘just when so many photographs strive to mimic painting comes a painter who lends his genius to the mimicry of photographs … this painting that makes a pleonasm of the image denounces the image which make a pleonasm of the world’. By forcing a second reckoning with the photographic image in painting, Bourdieu continued, ‘the image of the image reveals the inherent blunder of quotidian vision, of the distracted gaze that gives a false immediacy [transforme en ‘actualité’– inactuelle] to all that it encompasses’.43 While Bourdieu argued that Rancillac’s merging of mechanical and manual representation forced a confrontation between the photographic reality effect and the mediating function of art, Rancillac considered his painting to have détourned the techniques of pop art in order to ‘radically renew the expression of present-day reality’. While Rancillac considered the realism of Jeune Peinture to be ‘ancien figuration’, the role of mechanical techniques in his method of ‘dialectical realism’ was to forge a style that was both technically modern and politically engaged.44

Fig.19

Cuba Colectiva 1967

Oil on canvas

Courtesy Museo Nacionale de Bellas Artes, Havana, Cuba

In an interlude that would have an important impact on the Atelier Populaire, Rancillac travelled to Cuba in the months following his L’année 1966 exhibition along with Aillaud, Arroyo and Recalcati as a member of a contingent of French artists and intellectuals who participated in the Salon de Mayo. This transposition of the French Salon de Mai in Havana resulted in the collectively produced mural Cuba Colectiva, measuring a massive eleven by five metres (fig.19). The mural is a cacophonous hand-painted spiral of images and text that manifests a wide range of political orientations and artistic competencies. However, as art historian Thomas Crow has detailed, the trip exposed the French artists to Cuban revolutionary billboards and posters that subsumed flattened photographic images of Fidel Castro, Che Guevara and others into public graphic displays.45 While the trip to Cuba left divisions between the members of the Salon de la Jeune Peinture and painters like Rancillac intact, it confirmed the street-level relevance and graphic potential of ready-made photographic images suggested in Rancillac’s ‘dialectical realism’ works of the preceding year.

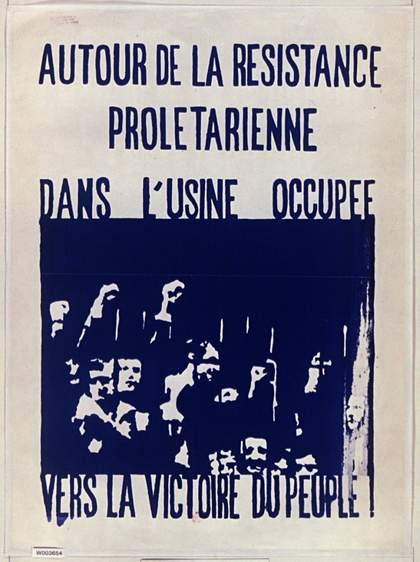

Fig.20

Autour de la résistance prolétarienne dans l’usine occupée vers la victoire du peuple 1968

Photographic poster

© Bibliothèque nationale de France

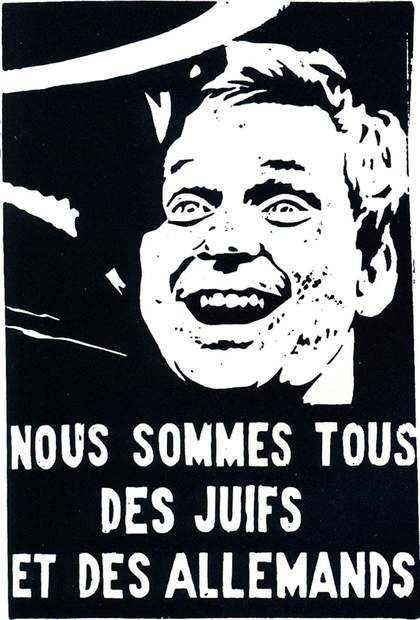

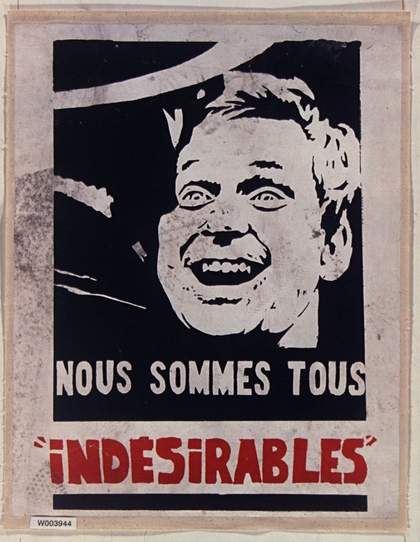

Entering the convulsive atmosphere of the Atelier Populaire less than one year after the Cuba trip, Rancillac applied his technical knowledge of the opaque projector to poster designs that combined manual and mechanical representation to flatten and abstract photographic source images. For instance, in Autour de la résistance prolétarienne dans l’usine occupée vers la victoire du peuple (Around Proletarian Resistance, In the Occupied Factory, Towards the Victory of the People) (fig.20), the raised fists echo the iconography of solidarity conveyed in hand-drawn posters, despite their photographic source. Indeed, the pop-inflected abstraction of photographic images through the synthesis of hand and machine, as well as the ‘dialectical realist’ method of juxtaposing images and political vantages, subtends what has become one of the most iconic images associated with May 1968: Rancillac’s depiction of student leader Daniel Cohn-Bendit. Produced in two versions – Nous sommes tous des juifs et des allemands (We Are All Jews and Germans) (fig.21) and Nous sommes tous ‘indesirables’ (We Are All ‘Undesirables’) (fig.22) – Rancillac used an image of Cohn-Bendit by the photographer Jacques Haillot (fig.23) which captured Cohn-Bendit singing the Marseillaise in the face of a helmeted CRS officer upon emerging from a meeting with administrators at the Sorbonne on 6 May. As the strikes reached an apex on 21 May the government ordered the revocation of Cohn-Bendit’s French passport while he was on a lecture tour in Berlin, sparking more protests on his behalf in Paris. That day Rancillac was asked to design a poster of Cohn-Bendit with the text ‘we are all Jews and Germans’, referring to the anti-Semitic and xenophobic pronouncement of the right-wing weekly Minute on 2 May – ‘this Cohn-Bendit, because he is Jewish and German, takes himself to be the new Karl Marx’ – which was repeated in a milder version on 3 May by Georges Marchais, Secretary of the French Communist Party, who denounced ‘these groupuscules led by the German anarchist Cohn-Bendit’.46

Fig.21

Nous sommes tous des juifs et des allemands 1968

Photographic poster

The night of 21 May Rancillac returned to his studio in the Latin Quarter and using the opaque projector drew the Haillot photograph by hand before transferring the design to silk with drawing gum and returning it to the Atelier Populaire for printing.47 However, when he arrived at the studio the next morning the text of the poster had been changed from ‘We are all German Jews’ to the anodyne ‘We are all undesirables’ in an apparent effort by those in the workshop aligned with the French Communist Party to avoid further tensions with Marchais and the party leadership. As the poster was mounted and carried on placards during a rally to protest Cohn-Bendit’s interdiction, however, the chant among the crowd reverted to the original slogan, which Rancillac took as a sign of the power of the street over those at the Atelier. In his physical absence Cohn-Bendit was evoked in reference to the subjective annihilation of the Holocaust and, according to philosopher Jacques Rancière, given ‘a form of visibility conferred upon something that is supposedly non-visible or that has been removed from visibility’.48 Cohn-Bendit’s abstraction in the figure of a ‘German Jew’ was doubled in Rancillac’s graphic in which, to follow Alloway again, ‘the fading or loss of detail that occurs within silk-screened images is like life itself when it has been photographed and reproduced’.49 By abstracting a press photograph of the events and soliciting identification with ‘an impossible subject’, Rancillac’s poster eloquently subverted the state media’s representational regime.50 Furthermore, the striking axial opposition of the officer’s helmet with Cohn-Bendit’s jubilant and exposed face echoed the formal device underlying Rancillac’s ‘dialectical realist’ method, providing a powerful confirmation of its political relevance in the street.

Fig.22

Nous sommes tous indésirables 1968

Photographic poster

© Bibliothèque nationale de France

Fig.23

Daniel Cohn-Bendit 6 May 1968

Photograph

© Jacques Haillot

Art historian Michael Lobel has argued that Lichtenstein’s use of the opaque projector to project and paint drawings of comics signals an ambivalent merging of body and machine, springing on one side from the ‘dream of pure, unmediated vision, couched in the technological language of the machine. On the other the belief in a perceiving subject whose imperfect corporeality denies access to such transcendence’.51 Although his works are often imbued with a gritty materiality, Warhol similarly disavowed hand painting stating, ‘in my artwork hand painting would take much too long and anyway that’s not the age we live in … mechanical means are today … silkscreen work is as honest a method as any’.52 Rancillac’s conflation of machine and handwork in paintings such as Enfin silhouettes affinées jusqu’à la taille registers Lichtenstein’s ambivalence while stopping short of Warhol’s disavowal. However, the final step of silkscreen printing sent his process into quasi-industrial production at the Atelier Populaire, ushering it from the realm of fine art to that of graphic design and street politics. This fusion of the manual and the mechanical in the opaque projector and the silkscreen allowed the Atelier Populaire to convey a politics in the street-level billboard spaces of display that French artists such as Daniel Buren, the Affichistes and the Situationists had cultivated over the past decade. Following Rancillac’s description, it also constituted a détournment of pop art’s conflation of painting and media image in service of a popular art negotiated with and for a dissenting public.

While the use of pop techniques by Rancillac and others in the Atelier Populaire may seem contradictory, they provided a source of artistic engagement that functioned beyond the limitations of the canvas and the confines of the gallery. By bringing the symbolic density of painting together with the ephemeral visibility of graphic design, the Atelier Populaire turned pop art’s high-low dialectic on its head and highlighted a persistent dilemma of modern political art that Gilles Aillaud voiced in December 1968:

must one conclude that in order to play even the smallest role in ideological struggle art must reduce itself to the simplest of forms? It would be strange to think that in order to be effective art must divorce itself from the majority of its means. The last and most positive of our experiences thus poses more problems than it solves.53