The American Paul Thek (1933–1988) gained early success with a series of mixed-media sculptures titled Meat Pieces (later renamed Technological Reliquaries), first shown at the Stable Gallery, New York, in 1964. The series comprised plaster and wax casts of Thek’s face, arms and legs as well as slabs of tissue moulded in wax, enclosed in vitrines that spliced the geometry of minimalist sculpture with the carnality of a Catholic shrine. This project reached a climatic point in The Tomb 1967, which consisted of a full-size effigy of the artist painted pale pink and displayed on the floor of a wooden ziggurat of the same feminine colour. A black-and-white photograph taken when the first version of the work was shown at the Stable Gallery in September 1967 shows the inside of the structure, revealing that viewers would have ascended a ramp to look down on the figure from above and thus would have been distanced from it (fig.1).1 Inside the tomb the figure was dressed in painted jeans and a jacket, which hid the wooden torso, and had psychedelic medallions placed its cheeks. Its head rested on two pillows while the shoulder-length blonde hair, eyebrows, eyelashes, and moustache enhanced its corporeality; medallions also decorated the necklace made of hair that hung around its neck. Next to the figure Thek had arranged objects including glass goblets, private letters and a pouch containing the wax fingers severed from the bloody right hand. Although nearly everything was painted a uniform pink, colour photographs taken in Thek’s studio by the artist’s lover Peter Hujar reveal that the figure’s tongue was blue (fig.2). While some commentators have described the anomalous detail of the blue tongue as ‘poison-blackened’, it may also be read as a sign of putrefaction and volatility, at odds with the sanitised notion of a wax effigy.2 Lying in state yet allowed to rot, this corruptible effigy became a complex and contradictory requiem for the American counterculture, reflected in its alternative, unauthorised title Death of a Hippie.3 This article thus takes its cue from various readings of the work, including the artist Mike Kelley’s influential 1992 claim that it signalled the ‘pretty decay’ of a decade whose dirtiness became sanitised in historical memory.4

Fig.1

Paul Thek

The Tomb (interior view), Stable Gallery, New York 1967

© The Estate of George Paul Thek; courtesy Alexander and Bonin, New York

Photo: John D. Schiff

Fig.2

Peter Hujar

Thek Studio Shoot: Thek Working on Tomb Effigy 8 1967

© The Peter Hujar Archive LLC

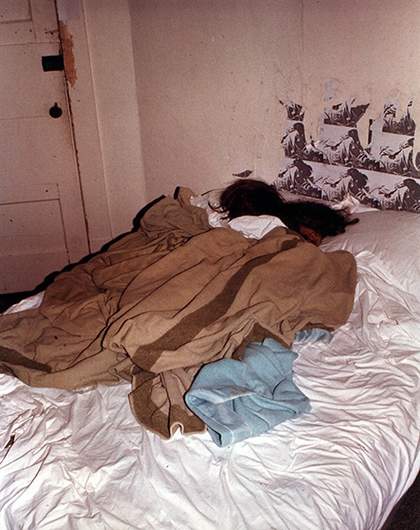

In the twentieth century many artists cast body parts using wax or other materials, including Marcel Duchamp, Jasper Johns, Bruce Nauman, Tetsumi Kudo, Robert Gober, Duane Hanson, Gavin Turk, Alina Szapocznikow, Kiki Smith and Ron Mueck. Somewhat selectively this article considers the early sculptures and installations of Thek, which are an acknowledged part of the anti-formalist narrative, together with the early work of San Francisco-based artist and filmmaker Lynn Hershman Leeson (born 1941), who is perhaps better known for her pioneering work in new media.5 From 1963 Hershman Leeson also cast parts of her own face and hands in wax, integrating these pieces into installations situated outside the gallery. Augmenting them with make-up, wigs, glass eyes, as well as interactive sensors and audio components to simulate bodily processes and reactions, Hershman Leeson, like Thek, also encased her modular body parts in materials like Plexiglas or recycled them into site-specific installations, plugging the figures into larger cultural narratives about power, technology and gender. The most famous of these was The Dante Hotel 1973–4, a room-size environment that stayed open around the clock for nine months at a San Francisco flophouse. Always in flux, the work comprised imaginary composites of the hotel’s inhabitants, taking the form of two life-size figures whose only exposed parts were their wax heads and hands (fig.3).6 When the police shut down the installation, Hershman Leeson’s effigy took a new form in the alter-ego Roberta Breitmore 1974–8. Brought to life by the artist and other performers, this alter-ego was both a confessional self-portrait and a composite of abject feminine stereotypes; she left behind tangible tokens of her existence such as a driver’s licence, a dental X-ray, surveillance photographs, and a psychiatric report.

Fig.3

Lynn Hershman Leeson

The Dante Hotel 1973–4 (detail)

Site-specific installation at the Dante Hotel, San Francisco

© Lynn Hershman Leeson

Hershman Leeson’s and Thek’s effigies provide a lens through which to perceive the confluence of political power and individual sovereignty in America in the 1960s and 1970s. Both stage the effigy at a point of putrefaction – the blue tongue of Thek’s figure, the duration of The Dante Hotel installation – evidencing the political as well as corporeal volatility of the subject. This was to some extent achieved by both artists’ subversion of the effigy as a form of representation. In The King’s Two Bodies (1957) German historian Ernst Kantorowicz explained how the royal corpse threatened the symbolic continuity of power, thus prompting the production of a more durable substitute for public display upon death.7 What Kantorowicz identified in his book on the prehistory of modern ‘political theology’ was elaborated on by the philosopher Michel Foucault in a 1975–6 series of lectures at the Collège de France, in which he defined the concept of biopower.8 Foucault modified earlier theories, which understood sovereignty as the divinely ordained right to ‘take life or let live’, to argue that the state now had the authority ‘to make live and to let die’.9 Where individual bodies were subject to disciplinary techniques under medieval regimes, modern political regimes inaugurated in the later eighteenth century applied these techniques to entire populations.10 Individuals only mattered in terms of what data they could yield about the masses; in extreme cases this data could be used to strip citizens of their rights and place them under a ‘state of exception’, a term coined by juridical theorist Carl Schmitt to refer to a sovereign’s ability to transcend the rule of law.11 The political philosopher Giorgio Agamben has followed Schmitt by reviving the obscure Roman legal term homo sacer (sacred man) to connote the idea of a ‘bare life’, what the ancient Greeks called zoē and distinguished from bios, the politically acknowledged and thus protected life of a citizen.12 In that they both exist outside or beyond the law, the sovereign at the top of the social ladder and the homo sacer at the bottom are thus oddly aligned.13

The productive intermingling of death and vitality in these two bodies of work made them an ideal vehicle to challenge the constellation of technologies, institutions and discourses that Foucault named ‘biopower’. Thek’s entombed hippie, which bore his likeness, and Hershman Leeson’s equally entombed yet perversely vital effigies of marginal women can both be understood as confronting biopower through the perspective of the counterculture and other movements that flowered (and declined) in 1960s and 1970s America. Like Thek, Hershman Leeson exploited the associations that wax has with volatility and subversive mimicry. As a material ‘insensibl[e] to contradiction’, wax’s ability to take imprints of the unique landmarks of the skin connects it to strategies of surveillance and data collection that measure visual, behavioural or chemical characteristics, connecting Hershman Leeson’s hotel tableau to her later invented character.14 The artist described Roberta Breitmore as ‘my flippant effigy’ and ‘a dark, shadowy, animus cadaver’.15 Similarly, The Dante Hotel was for the artist simultaneously a scene of death and ‘a means of survival’.16 As such Thek’s and Hershman Leeson’s volatile effigies connect two very different bodies of work and different political movements – the counterculture, gay rights, women’s liberation – to make visible the restraints placed on the subject. Thek and Hershman Leeson infused the incorruptible effigy with signs of rot and thus ruptured and subverted the image of sovereign power.

From box to tomb

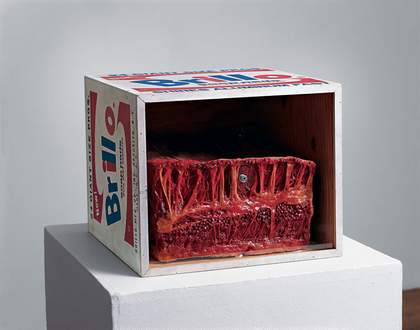

Paul Thek began making his Meat Pieces after a 1963 trip to Sicily sponsored by Princess Topazia Alliata, who had earlier shown his work at Rome’s Galleria Trastevere. While visiting the Capuchin ossuary near Palermo he was deeply moved by the sight of countless corpses stuffed into niches and arranged on shelves. In a 1966 interview he described how it felt to open a glass box and touch ‘what [he] thought was a piece of paper’ but turned out to be ‘a piece of dried thigh’.17 This uncanny experience, coupled with the artist’s interest in bodily thingness, directly informed works such as Untitled 1966, in which sheets of neon-yellow Plexiglas enclose a cylindrical slab of tissue oozing green slime. In addition to these works the artist also cast his own head and limbs in wax and plaster. Warrior’s Leg 1966–7 and Warrior’s Arm 1967 feature bloodied appendages in clear single-layer vitrines, their horror muted by the campy gladiatorial accessories that give them the appearance of Hollywood props. In Untitled (Self-Portrait) 1966–7 Thek placed a facial cast coloured a psychedelic pattern, with realistic porcelain teeth and a red pierced tongue, on a ziggurat base at the bottom of a clear vitrine. The most famous of this series, Meat Piece with Warhol Brillo Box 1965, comprised one of Andy Warhol’s iconic packaging replicas, which was upended and filled with simulated meat perforated by plastic tubing (fig.4). Here Thek intervened in readings of Warhol’s work that rendered it synonymous with the vacuity of postmodernism.18 As art historian Ileana Parvu has written, the work reimagined pop as ‘an exteriorized object whose interior has been playfully demystified as “mere meat”’.19 Thek’s appropriation and revision of Brillo Soap Pad Box foregrounded a meatier, less sublimated side of pop and suggested a new dimension of biopolitical critique. The plastic tubes recall a life-support system or perhaps a device for behavioural surveillance, like the transparent chamber designed by psychologist B.F. Skinner to study ‘operant conditioning’, which reduced the individual to a set of involuntary behaviours and bodily responses.

Fig.4

Paul Thek

Meat Piece with Warhol Brillo Box 1965

Wax, painted wood and Plexiglas

Philadelphia Museum of Art

© The Estate of George Paul Thek

Although different, The Tomb, like the Meat Pieces, can be read as a critique of forces that subject individuals to psychological surveillance or reduce them to bare life. However, unlike the obscure bodily fragments that made up the earlier series, the figure in The Tomb depended on some semblance of individuality, something which was also lacking from much hyperrealist art of the time. The artist Duane Hanson, for instance, enhanced the lifelikeness of his fibreglass, polyvinyl and bronze casts, based on real individuals, with paint, hair, clothes, and objects befitting their social status, such as shopping carts, lawn mowers, garbage cans and mops. John de Andrea’s gypsum casts of idealised young women fabricated in bronze or polyvinyl were also painted realistically in full colour. While Hanson’s figures at least indulge in a more diverse fantasy of American normativity, de Andrea’s homogeneous nudes needed no props to inhabit the abstracting void of the white cube; their poses alone made them objects of the male gaze. As the critic Kim Levin wrote in 1974, these figures gave the impression of being ‘tranquil, and vacant, with no private thoughts – bodies for sale’.20

Far closer to Thek’s installation in this respect were the works of George Segal and Edward Kienholz, both of whom also placed their casts inside built environments. Unlike the hyperrealist sculptors, Segal left his plaster casts unpainted but arranged them in near-perfect polychrome simulations of a gas station or a diner, forcing a contrast between figure and ground that counterintuitively rendered the monochrome figures more real. Calling to mind the ill-fated Pompeiians whose forms were captured by molten ash when Vesuvius erupted, Segal’s figures register more as victims of natural phenomena than as man-made artworks.21 Similarly, Thek’s mostly monochrome figure might be said to represent silent interiority. But unlike Segal’s distinction between the figure and the environment, in Thek’s installation each part was brought together inside the tomb structure, which was bathed in an ‘incensed haze’ and ‘dim pink light’.22 This resulted in a hallucinatory environment, the boundaries of which were indistinguishable from the boundaries of the body. In addition to dissolving these boundaries between the figure, beholder and environment in which everything was immersed, Thek also invited viewers to enter the space fully, whereas Segal’s installations did not encourage the same immersive experience. The evidence of an inscrutable interiority was perhaps strong enough to overcome the generality imposed on the figure by the work’s second, pejorative title; Death of a Hippie refused to dignify the subject as an individual, but nor did it deem the figure to be universal. This paradox was well-illustrated by the figure’s jeans, which were simultaneously the most generic item of clothing and the most personal (they have been called a ‘second skin’).23 Indeed, it is tempting to compare these clothes to those worn by Hanson’s figures, whose costumes were also described as ‘equally coverings, skins’.24 In intensifying the continuity between the figure’s clothes and skin by painting them the same pink shade, Thek worked counter-intuitively against the generalising effect of the hyperreal figures. In this way Thek combined the disturbing lifelikeness of the hyperreal with the abstraction of monochrome sculpture to destabilising effect.

Before exhibiting The Tomb in the Walker Art Center’s Figures/Environments show in 1970, Thek voiced his displeasure over the ‘hippie’ label to the museum’s director, forbidding any further ‘mention of Hippy, Death of, Life of, anything’ from the press, and arguing that his work was incompatible with a ‘commercialized chic revolution’.25 Thek may have been responding to the denigration of the hippie in both mainstream and radical America; a month after The Tomb first went on view, on 6 October 1967 in Buena Vista Park, San Francisco, the community action group The Diggers held a very public funeral for ‘the hippie’, complete with a coffin and pallbearers, calling the hippie a ‘devoted son of the mass media’.26 Peculiarly, the response from this anarchist group paralleled the mainstream reaction to hippiedom and its epicentre in Haight-Ashbury, San Francisco, which played host to experiments in communal living, free stores and clinics, psychedelic rock, promiscuity, flower power, Hinduism and Zen, indigenous rituals, opportunistic gurus, and hallucinogenic drugs. As writers Peter Braunstein and Michael William Doyle have shown, the complexity and multivalent nature of 1960s counterculture is often reduced in historical accounts to a series of defining moments: the 1967 ‘Summer of Love’, for example, followed by the Manson Family murders and the violence at Altamont in 1969.27 Rather than considering the terms ‘hippie’ and ‘counterculture’ to be synonymous, Braunstein and Doyle argued that ‘it may be safer to consider the “hippies” as an ideological charade adopted temporarily by some “counterculturists”, but then dropped by 1968–69, after which the term persisted as an assumptive signifier to designate a look, a fashion, an attitude, or a lifestyle’.28

The prolonged death of the hippie was only one scene of violence enacted in front of the American media during the 1960s. The spectacle of President Kennedy’s Dallas assassination in November 1963 along with the shootings of civil rights leaders Medgar Evers earlier that same year and Malcolm X two years later all resonate in The Tomb. However obliquely, Thek’s work could also be seen in relation to the shootings of Robert F. Kennedy and Martin Luther King, Jr. in 1968; the riots provoked by King’s death in cities like Detroit, Washington, D.C., and Chicago; the drug-related deaths in 1970 of psychedelic rock musicians Janis Joplin and Jimi Hendrix; and the killing by National Guardsmen of unarmed students at Kent State University that same year, followed by two more student deaths at Jackson State University at the hands of the police. The spectacle of death at home paralleled media coverage of wartime atrocities perpetrated by American soldiers in Vietnam, mobilising the anti-war movement from 1968 onwards and doing much to expose President Nixon’s cold-war agenda. As the government needlessly prolonged the war until 1973, it fought a second one at home, using police brutality and mass surveillance to repress social struggles like the counterculture and the increasingly radical New Left and civil rights movements. Thek’s figure fits provocatively into this history of volatile bodies, so that even as the figure appears to turn away from unrest – perhaps as a victim of violence looking inward for spiritual refuge – the work still seems to lament the loss of freedom more broadly, as well as freedom from stereotyping.

In ‘Death and Transfiguration’, an essay commissioned for Thek’s posthumous retrospective at the Castello di Rivara, the artist Mike Kelley characterised the entombed figure as a surrogate for the failed countercultural phenomena, with Charles Manson and the Hell’s Angels announcing ‘the degraded end of hippie utopianism and the beginning of the notion of hippie as criminal burnout’.29 However influential this reading, it is also idiosyncratic. Alex Heil, for example, has suggested that Thek conceived of his effigy from ‘an exclusively [Western] European vantage-point’ where ‘utopias at least seemed possible’ and ‘the dropout, the communard, the attribute given to the far more “leftist” artist, had not been negatively labelled’.30 Kelley’s narrative instead depended on his own interest in Sigmund Freud’s notion of unheimlich, or ‘the uncanny’.31 A year after ‘Death and Transfiguration’ Thek appeared again in another essay that Kelley wrote to accompany The Uncanny, an exhibition he curated of figurative sculpture at Sonsbeek 93, Arnheim, expanded in 2004 for Tate Liverpool and mumok in Vienna.32 Built around the idea that ‘[n]o accumulation of mere matter can ever replace the loss of the archetype’, The Uncanny equated ‘matter’ with the uncanny realism of polychrome sculpture and the ‘archetype’ with its forbear, the classical statue.33 The exhibition came out of Kelley’s research for Heidi: Midlife Crisis Trauma Center and Negative Media-Engram Abreaction Release Zone 1992, an installation and performance-based video work made with Paul McCarthy and shown in the exhibition LAX at Vienna’s Galerie Krinzinger that year. Adapting Johanna Spyri’s children’s novel into the style of a 1970s slasher film, Heidi reimagined the archetypal grandfather as a depraved patriarch mistreating the book’s young protagonists, whose trauma became analogous to the televisual ‘abuse’ perpetuated on impressionable minds by such ‘wholesome’ classics. With this in mind Thek’s effigy was a crucial precedent for Kelley and McCarthy’s interest in the degraded archetype, which heralded a return in American art to the body and the intersection of individual and cultural trauma. When the bisexual Thek – to whom the writer Susan Sontag dedicated Against Interpretation in 1966 – died of an AIDS-related illness in 1988, having become largely neglected by the same establishment that had fêted him two decades earlier, The Tomb became a powerful symbol of national silence and a necropolitical edict.

Biopolitics and necropolitics

Foucault aligned biopower with the deployment of new techniques to produce and maintain biological life.34 Biopower’s sphere of concern extended from the individual citizen who could be put to (or spared from) death to the birth rate, living environment, hygienic habits, infirmity and health of the general population. Where only the individual body had gone through the disciplinary paces, now biopower inaugurated ‘a new body, a multiple body, a body with so many heads that, while they might not be infinite in number, cannot necessarily be counted’.35 As Foucault first suggested, biopolitics can easily flip into its obverse – thanatopolitics or necropolitics – where death becomes the object of sovereign decision. In this way state power depends on a degree of volatility, because its authority relies on a foundational instance of lawlessness needed to declare the law into being. Designating ‘violence as the primordial juridical fact’, Agamben has claimed that the ‘Law is made of nothing but what it manages to capture inside itself through the inclusive exclusion of the exceptio’; state power is thus not contractual in nature but founded on the state of exception.36 Agamben has also posited a blurring of boundaries between constituted power and constituting power in order to ‘correct’ Foucault’s neglect of the intersection of juridico-institutional and biopolitical models of power.

Just as The Tomb gestured to pre-modern rituals protecting power’s passage from one mortal body to another, the work also destabilised this structure in several ways. First, the hippie assumed the role of the sovereign’s incorruptible effigy only to corrupt it through signs of rot, both literal (the blue tongue) and ‘moral’ (the ‘sissy’ pink colour of the installation as Kelley described it).37 Second, the hippie usurped the place of the sovereign, replacing it with a dispossessed individual whose body bore signs of violence. From this perspective the fingers, severed from the figure’s right hand and then put in a pouch, read as necropolitical trophies taken by the enemy, here equated with the American state. For Kelley, who never named these forces, the contents of the pouch resembled, among other things, ‘kill tokens taken by soldiers in Vietnam who fashioned necklaces of human fingers, like the genitals hacked off and stuffed into the mouths of lynched blacks’.38 As such the severed fingers were more than just functional digits, indispensable to an artist who was as good as castrated without them: they were transformed from the tools that make the autographic mark into surfaces with printable patterns for biometric identification. Thek was clearly not the only artist emptying out the indexical gesture linked to personal expressivity in this way. Better-known artists are Marcel Duchamp, Jasper Johns and Bruce Nauman. In fact, Thek began to experiment with casts in response to those made by Johns a decade earlier under the influence of Duchamp, whose Étant Donnés 1946–66 was unveiled at the Philadelphia Museum of Art in 1969. Also, through Johns’s translation of Duchamp’s earlier casts, Nauman cast his wife’s left arm and part of her face to make From Hand to Mouth 1967, a tautological work whose poverty of means nevertheless escapes conceptual closure. Like other works by Nauman, such as Neon Templates of the Left Half of My Body Taken at Ten Inch Intervals 1966, which took the measure of the artist’s body, literalism verges on disciplinary violence here. If Nauman’s casts move tacitly into the realm of biometrics, recalling anthropologist Alphonse Bertillon’s early attempts to identify criminals by measuring the size of certain body parts, Thek’s fingers called up timelier associations, including the fingerprint scanner whose prototype the FBI would develop less than a decade later in 1975.39

Research into an automated identification system had begun in 1969 under FBI director J. Edgar Hoover. Also under Hoover’s directorship, the surveillance program COINTELPRO infiltrated various subversive groups led by students, anti-war activists, black community organisers, workers’ advocates, communists and feminists.40 The anti-war movement resulted in alliances between these groups, evidenced in large-scale demonstrations that included war veterans, black activists, leftist Zionists, American Indians, feminists, professional associations, national guardsmen, and many others.41 The Nixon administration used COINTELPRO and media hype to capitalise on stereotypes to divide and conquer this groundswell of united differences. It is in this context that Thek’s interest in a kind of non-belonging and his refusal of the label ‘hippie’ might be seen as a political gesture. As Harald Falckenberg has put it, Thek ‘understood freedom above all as a freedom from identification’ and claimed that the only revolution that interested him was the internal kind.42 To drop out of society can be a form of passive resistance, an analogue for how novelist Herman Melville’s character Bartleby the Scrivener responded to every request: ‘I would prefer not to’.43 To shed one’s social identity is to become, for Agamben, what ‘the state cannot tolerate in any way’ and will always fight: a situation where ‘singularities form a community without claiming an identity’, where ‘human beings co-belong without a representable condition of belonging (being Italian, working-class, Catholic, terrorist, etc.)’.44

The biopolitical subtext of The Tomb supports a number of anachronistic readings, particularly the one in Kelley’s 1992 essay on Thek, which rehabilitated the artist when the traumatised body gained a new significance in light of the AIDS pandemic. Kelley saw Thek’s degraded archetype as heralding the end of 1960s utopianism, announcing the consequences of unrestrained sexual freedom and recreational drug use in the 1980s. Given the initial connection between the disease and stigmatised minorities like gay men, heroin users, sex workers and Haitian immigrants, the American government’s belated response to the health crisis has been called a necropolitical act. When President Reagan infamously neglected to mention AIDS in a public context before 17 September 1985, Larry Kramer, writer and co-founder of the Gay Men’s Health Crisis (GMHC) and later the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP), declared his silence to be a form of ‘genocide’.45 The work of Robert Gober provides an important contemporaneous parallel to Thek’s work. Gober’s wax-cast legs – which protrude uncannily from walls, sometimes covered in votive candles, or perforated by ‘Pentecostal’ drains – allegorise possible responses to AIDS, from the societal anxiety about porous bodily boundaries as a site of contagion to gestures of mourning and remembrance.46 Seen through the prism of Gober’s work, Thek’s effigy seems to lose its boundaries all the more, merging dangerously with an environment the colour of fairy dust, one whose spiritualist turn towards abstraction had an elegiac quality.

From tomb to bedroom

Fig.5

Lynn Hershman Leeson

Sleeping Woman Dreaming of Escape 1968

Wax, makeup, glass eye, feathers, hair and Plexiglas

© Lynn Hershman Leeson

Lynn Hershman Leeson’s early life-cast piece, Sleeping Woman Dreaming of Escape 1968 (fig.5), is comprised of a wax facial cast of the artist, its features picked out with dark paint, a wig, and a single glass eye. The head rests on its side in a rectangular Plexiglas box, the half-open eye seeming to peer beyond the transparent top. Compared to Thek’s Untitled (Self-Portrait), where the psychedelic face appears to have penetrated some mystical membrane separating the material world from another plane of reality, the figure in Sleeping Woman Dreaming of Escape appears trapped, perhaps visualising the elusive prison of narrow social circumstances imposed on real flesh by gender constructions. In another cast piece from the same period, Self-Portrait as Another Person 1966–8, Hershman Leeson painted the wax head darker to indicate solidarity with women involved in the civil rights struggle who experienced oppression on multiple fronts.47 When these early cast works were shown in 1971 at the Berkeley Art Museum, they were incorporated inside a simulated hotel room and accompanied by a playback device triggered by approaching viewers that played a recording of ‘random provocative dialogue’.48 Having invited Hershman Leeson to exhibit her work only after the institution’s exclusion of women threatened its funding, the museum deemed the sound element inappropriate for the venue and closed the exhibition.49 As a consequence the artist began to think about non-traditional sites for her installations, eventually creating The Dante Hotel in 1973 and abandoning the frame of the art gallery altogether.

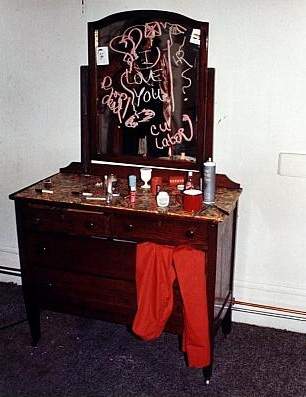

There are a number of obvious parallels between The Tomb and Hershman Leeson’s work, particularly around the process of casting, the construction of a built environment and self-portraiture. However, the differences are also important in highlighting the potential of a biopolitical critique from a feminist perspective. While Thek’s figure had inhabited the sanitised white cube, Hershman Leeson scouted a cockroach-filled hotel, The Dante at 310 Columbus Ave, which one critic described as the ‘historical and geographic epicenter of Nipple City’.50 She found this location with fellow Bay-area artist Eleanor Coppola, who rented room 43 and installed a separate work there that also opened on 30 November 1974, involving a man living in the room round the clock.51 Inspired in part by the museum’s earlier rejection of her politicised sound work, Hershman Leeson combined three main sources of pre-recorded sound in room 47: first, Irish actress Siobhan McKenna reciting Molly Bloom’s soliloquy from Ulysses on a playback device in the closet; second, recorded breathing under the bed; and third, a local news broadcast to connect the scene with the outside world. The Dante Hotel simultaneously looked like a mausoleum lost to time and a crime scene awaiting discovery. Another critic remarked that whoever entered was neither a proper protagonist nor an outside observer, but more ambiguously just one element among others inside the tableau.52

Fig.6

Lynn Hershman Leeson

The Dante Hotel 1973–4 (detail)

Site-specific installation at the Dante Hotel, San Francisco

© Lynn Hershman Leeson

When asked about the deathly connotations of The Dante Hotel Hershman Leeson called the installation ‘a means of survival’.53 Perhaps this gestured to the exhibition taking place despite the prior institutional censorship she had experienced, but it may also allude to the work’s narrative elements as well as its personal meaning for the artist. Unlike Thek’s effigy, which was comparably serene, Hershman Leeson’s installation staged a scene of violence and death. Bathed in pink and yellow light from exposed lightbulbs, the room was filled with ephemera, including eyeglasses, magazines, hair rollers, lipsticks, rouge, tampons, cigarette butts, empty medicine vials, clothing, birth control pills, private letters and two goldfish swimming in a murky fishbowl, reflecting the figures’ dismal situation (fig.6). These objects contributed to the impression that the women were ‘trapped, encased with their artifacts for witnesses to discover’.54 But they also communicated ‘the education, personality and socio-economic background of [room 47’s] presumed occupants’.55 The installation closed nine months later, when a man visited at three o’clock in the morning and mistook the wax figures for corpses and called the police, who confiscated the room’s contents.56

The similarities with The Tomb become more apparent when considering the role of wax in crafting the facial likenesses. Philosopher and art historian Georges Didi-Huberman has argued that this material’s capacity for resemblance ‘always goes too far’, whatever the maker’s intentions, and that what looks like pliability and passivity at first soon ‘reverses itself and becomes the power of the material’.57 The volatility of wax has a certain affinity with the contradictions of the counterculture, which was at once peaceful and violent, engaged and apolitical, a rejection of consumerism and yet easily reified.58 Endemic to the end of the 1960s, these contradictions also reflected the fracture between what writer Edward P. Morgan called ‘the prefigurative creation of a new democratic community and the instrumental drive to transform institutions’.59

Shying away from instrumental politics, the counterculture tried to dissolve the same hierarchical values inherited from mainstream society that had alienated women from male-dominated organisations like the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and, to a lesser extent, the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS).60 As Debra Michals has shown, many early second-wave feminists were influenced by these liberation struggles as they translated hippie culture’s investment in ‘consciousness expansion’ into the more practical strategy of ‘consciousness raising’ encouraged through group sessions that preceded political action.61 The New York Radical Women (NYRW) – which was active between 1967 and 1969 and organised a protest around the Miss America pageant in 1968 – seized upon consciousness raising as a way to go ‘from self-discovery to social discovery, from self-actualization to social change’.62 Even as the radical promise of this practice became diluted by the language of self-help, the women’s movement became newly energised in the 1970s, a decade that saw some of its biggest gains, including the proposal of the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA), the passing of Roe v. Wade, and the founding of the National Black Feminist Organisation (NBFO).63 From one point of view The Dante Hotel revived what The Tomb had literally (yet not metaphorically) buried. If the defeat of participatory democracy after 1968 forced many to choose between the personal and the political, second-wave feminism insisted that the personal was political; it practised a prefigurative politics committed to enacting the desired model of social existence in the here and now.64 The Dante Hotel worked similarly, prefiguring two things in particular: the potential fragility of state power and the potential durability of the marginalised woman.

An ethical encounter

The Dante Hotel might also be seen as a feminist intervention in the conceptual legacy of Marcel Duchamp’s experiments with life-casting, especially since Hershman Leeson has cited his readymades as an influence on her own work.65 While the artist has not explicitly connected The Dante Hotel with Duchamp’s Étant Donnés, the comparison is useful as both confront the viewer with a disturbing scene charged with sexual violence, although from different gender perspectives. Whereas Hershman Leeson’s figures might be read as self-portraits, Duchamp composed the headless female figure from casts of body parts of his Brazilian lover Maria Martins and wife Alexina ‘Teeny’ Duchamp.

In her book The Civil Contract of Photography (2008) the theorist Ariella Azoulay observed that Duchamp’s figure looks like a ‘victim of sexual assault’, a detail seemingly unnoticed by its first audiences despite the fact, as Azoulay remarked, ‘it lay openly on the surface’.66 Azoulay used the peephole tableau to challenge Agamben’s definition of bare life as unrepresentable (and thus doubly marginalised) and as the potential foundation for a future politics beyond the nation state based on singularity over identity. The problem, she argued, is that the homo sacer bypasses the specificities of gender. While the male homo sacer is usually ‘suppressed and clothed in the garb of citizenship’, its putatively unrepresentable female counterpart is all too visible: her bare flesh is ‘given prominence, made manifest in the public space, openly displayed and sanctified – or abandoned – to a point where no citizen’s garb could conceal it’.67 In other words the sacralisation of women’s extreme vulnerability and dispossession needs another more nuanced paradigm.

The Dante Hotel offers one solution to the problem by rescuing the marginalised body from its negative associations. From one perspective Hershman Leeson’s torso-less heads presented the illusion of bodily presence from afar, making the headless figure in Duchamp’s tableau look all the more exposed by comparison, regardless of any intent to stage or critique the desiring gaze. From another perspective the later work potentially ‘corrected’ the exposed vulnerability on show in Étant Donnés, particularly once the ambiguity of Duchamp’s title is taken into account. Read through The Dante Hotel, the words ‘étant donnés’, or ‘being given’, acquire a kind of interpretative volatility. Refusing to reaffirm the woman as fetish object, The Dante Hotel asked viewers to look beyond what was given – the apparent scene of rape and murder – and reflect on other possible meanings within the work, including one that recasts the installation as something more triumphal and dignified, as ‘a means of survival’. It is no coincidence that The Dante Hotel offered entry into a tangible world filled with objects indigenous to the imaginary women’s environment. Personalising the real-world space, it primed male and female viewers alike for a heady experience of identification. Reconsidered through this lens, Duchamp’s final work might also be read as soliciting identification with the masculine voyeur and exploited feminine object until these stereotypes lose some of their power.

Like The Tomb, The Dante Hotel battled stereotypes by staging an encounter with the face and therefore the individual subject. In his 1961 book Totality and Infinity the philosopher Emmanuel Levinas famously discussed the encounter ‘proceeding from the I to the other, as a face to face’ as the foundation of a new ethics that sees the subject’s very being as dependent on recognition of the Other.68 The same face that Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari would later call an imperialist machine in their book A Thousand Plateaus (1980) was for Levinas a vehicle for recognising the Other’s vulnerability and demand for survival. The face is an ethical fulcrum: at every moment it presents something excessive as it ‘destroys and overflows the plastic image’.69 The wax effigy also contains meaning in excess of representation, functioning as a symbol of power and incorruptibility in the wake of deathly decay. The intransigence of the material intensified the call to recognise these women as subjects in The Dante Hotel. However, in Hershman Leeson’s work the incorruptibility of wax soon gave way to the very thing whose dead or living appearance it simulated and whose imprint it took: real flesh.

From wax to flesh

While there was nothing overtly countercultural about the iconography of The Dante Hotel, the exposure of the wax women to visitors’ constant scrutiny recalled the exploitative situations in which many hippie women had found themselves a few years prior. The allegedly feminine ideals of love, cooperation and sensual connection embraced in Haight-Ashbury opposed the objectification of women in consumer society. However, the scene still generated stereotypes for consumption by both the mass media and alternative press. According to historian Gretchen Lemke-Santangelo, one such stereotype was the air-headed hippie chick who gets enticed into taking hard drugs and can then ‘be talked into doing just about anything’. An example would be Goldie O’Keefe, a comic character portrayed by actress Leigh French in The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour (1967–70).70 As Lemke-Santangelo has explained, other such figures seemingly designed to allay parental (and male) anxieties about countercultural femininity were ‘the maternal, nurturing earth mother, and the foxy, sophisticated, ultrafeminine chick with almost supernatural intuitive powers’.71 Influenced by emergent feminist critiques, Hershman Leeson’s work took on a new life in 1974 to investigate what constituted feminine identity, culminating in Roberta Breitmore, ‘a simulated person who interacts with real life in real time’.72 Keeping the project going for four years, Hershman Leeson created the character to explore the increasingly negative circumstances facing a woman who had ‘to forage for herself in the San Francisco Bay Area during those tumultuous years of societal change’.73

Roberta Breitmore was an imaginary 30-year-old divorcée who checked into The Dante with $1,800 in her pocket, hoping to start a new life. Her costume included a blonde wig, hair ornaments, sunglasses, heavy make-up, and other items of clothing and accessories. A paradigm-shifting, durational artwork, Roberta Breitmore is an extraordinarily early instance of what art theorist Boris Groys has claimed only exists ‘under the conditions of today’s biopolitical age, in which life itself has become the object of technical and artistic intervention’.74 The heart of the project was the alter-ego’s interaction with the public, which the artist eventually delegated to Roberta’s three ‘multiples’ – Kristine Stiles, Helen Dannenberg and Michelle Larson – to verify that her own negative experiences were shared more widely.

As a living effigy Roberta no longer needed to be represented at a certain remove. Advertising in local newspapers, she met with forty-three blind dates or potential roommates. While some of her correspondents merely sought companionship, other encounters took a more sinister turn; once a costumed Hershman Leeson had to flee from a prostitution ring at the San Diego Zoo (she escaped by removing the disguise). Later that year Roberta’s artefacts went on view at the M.H. de Young Memorial Museum where a lookalike competition accepted contestants of all ages and genders. Anyone wishing to transform into Roberta themselves could consult Roberta Construction Charts #1 and #2 1975, two black-and-white photographs of the costumed artist annotated and enhanced with acrylic paint. In some places the marks obscure the artist’s likeness, making it easy to imagine Roberta to be cadaverous under the mask, a zombie without true interiority.

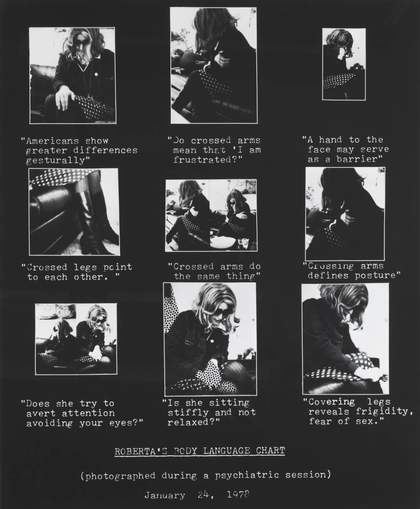

Fig.7

Lynn Hershman Leeson

Roberta’s Body Language Chart 1978, printed 2009

Photograph, gelatin silver print on paper

Tate

© Lynn Hershman Leeson

Roberta Breitmore was a character built on contradictions: the performance was based on forging an alternative identity while relying on the body of another, and although Roberta might be considered an ‘everywoman’, the project was, to some extent, tied to the artist’s personal experience of marital unhappiness and the desire to forge a new, independent identity. True to feminist art’s emphasis on personal experience as a key form of knowledge, Roberta wore a particular face and had particular experiences while remaining a representational assemblage that tended towards a certain generality.75 Catastrophe was around every corner: looking for a roommate, working odd jobs, going into therapy – everything that she did to avoid financial and physical ruin only led to new crises. Every move took Roberta a step closer to true marginality, stripped of the protections afforded to women who confirm to societal expectations. Hershman Leeson framed Breitmore through different modes of scrutiny and surveillance: a private investigator tracked her movements through the city, producing a stream of photographs, including one in which Roberta appears to be considering jumping off the Golden Gate Bridge; a body language chart was commissioned during her therapy sessions, registering every neurotic mannerism; even the green diary in which she recorded her experiences supplied material for professional handwriting analysis (fig.7).76 As a biopolitical entity Roberta was trackable and her governmental ‘existence’ was entirely the product of information that could be logged by the authorities. Her relics therefore included more than just personal belongings; they also comprised official identifications such as a driver’s licence, a dental X-ray and a psychiatric report.77

The character of Roberta Breitmore was a paradox. Despite the governmental identifications that validated her reality, she was the invention of an artist who did not identify with the composite of feminine stereotypes that she represented. Informed by, and indeed transforming the artist’s life experiences, the project produced a tension between truth and fiction that relates back to Didi-Huberman’s observations about the volatility of wax and the material’s tendency towards excess. This tension can be read into various elements of the project, including Roberta’s psychiatric sessions where Hershman Leeson was tempted to break character and obtain help for herself rather than ‘squander precious therapy on fictional trauma’.78 In this respect Roberta Breitmore connects to a later project, The Electronic Diaries 1986–98, a seven-part video testimonial in which simulated voices recount the artist’s true stories of her own childhood abuse. As critic B. Ruby Rich remarked apropos First Person Plural – the feature-length version of the diaries released in 1996, which combines the first five entries in the longer series – the doubles that appear at every stage of Hershman Leeson’s long career constitute the ‘summoning of a contemporary golem’, the mythical creature made from clay and animated to protect the Jewish people from annihilation.79 The Jewish artist, who lost many relatives in the Holocaust, was nevertheless undeterred to give testimony about her own experiences growing up in an allegedly normal middle-class family, even though it cast the historical victims of violence as new perpetrators. An excessive element apparently rooted in trauma links The Dante Hotel, Roberta Breitmore and The Electronic Diaries; this excess causes boundaries to blur between stereotype and lived reality, representation and the unrepresentable, truth and fiction.

Fig.8

Lynn Hershman Leeson

Roberta Multiple Is Exorcised with Flaming Vase (Michelle Larson) 1978

Photograph, gelatin silver print

© Lynn Hershman Leeson

Hershman Leeson’s feminist commitment to confessional truth, despite Roberta’s fiction, separates her alter-ego from the posing and performance of feminine types in works such as Cindy Sherman’s Untitled Film Stills 1977–80. For instance, art historian Amelia Jones has remarked that, although ‘media culture shows us that “identity” is only skin deep’ and any notion of an underlying reality false, Roberta Breitmore attests to there being an embodied remainder, ‘something [that] sticks to the image’.80 That remainder was so deadly in the case of Roberta Breitmore that the image had to be exorcised from the flesh. Through the body of Michelle Larson, Roberta was banished during a 1978 performance at the Palazzo dei Diamanti in Ferrara, an evocative location (the birthplace of Lucrezia Borgia) that called up the archetype of femme fatale. In the photo documentation of the performance Larson resembles an artificial body, an effigy used for a funerary procession (fig.8). In this respect the performance sought to stage the real and artificial, life and death. In her cadaverous guise, wearing Roberta’s wig and clothes, Larson entered through the palazzo’s archway, walking between identical glass vases that contained real and artificial flowers. Larson then turned Roberta’s repertoire of gestures into a dance before setting light to one of Roberta’s Construction Charts, the ashes of which were then collected in the vase that had contained the fake flowers. At the end of the ritual the Roberta multiple lay down ‘next to a coffin-like vitrine that held the relics of her life’.81

A photograph of Larson looking dead on the ground recalls two distinct rituals of power in a single mise-en-scène. The first ritual is the effigy burned in the absence of the individual whose crime merits a very public annihilation; the second is the dead sovereign’s body displayed in order to inspire reverence. More obliquely than Thek’s figure, the scene also recalls The Diggers’ hippie funeral in Haight-Ashbury following the commercialised ‘Summer of Love’. There is even an echo here of the New York Radical Women’s 1968 burial in Washington of a dummy named ‘Traditional Womanhood’.82 The performance could be read in tandem with the burning of ‘Traditional Womanhood’ as a cleansing ritual in which the burnt picture removes the toxic stereotype from Larson’s still-living body. Nevertheless, this was not without pain; to paraphrase Jones, the image still stuck to the flesh. Following the conclusion of the project and her subsequent divorce, Hershman Leeson described feeling like ‘a burn victim’ or like someone whose skin was peeled off with a ‘razor’, left ‘raw and exposed and bleeding’.83

The biopolitical effigy today

Despite the exorcism of Roberta Breitmore, the character has left a legacy in Hershman Leeson’s subsequent work and in her archive. The artist began to work with video in the late 1970s while investigating how bodies and identities were mediated by technology. Other important projects featuring alter-egos include Lorna 1983–4, the first interactive video art disc; CybeRoberta and her counterpart Tillie, The Telerobotic Doll 1995–8, both of which were exhibited in a physical gallery and interfaced with online communities; and Agent Ruby 1999–2002, an artificial intelligence that ‘lives’ on SFMoMA’s website and chats with visitors. In 2006 Stanford Humanities Lab reconstructed The Dante Hotel in the virtual world of Second Life two years after the university’s library purchased the artist’s archive. Located partly in different museum spaces and partly in the multiplayer environment, Life to the Second Power: Animating the Archive used the actual floor plan of the now demolished Dante Hotel to construct a simulacrum that would be explored by avatars, complete with a virtual concierge to take the visitors to the reconstructed room and archive.84 As a digital avatar, Roberta appeared again in this reconstruction of an earlier work, occupying a place between the living and the dead. However, in this context she also came to embody a critique of virtuality’s promise of endless new identities beyond biology’s limitations. Lying in state at her exorcism like the absolutist sovereign who incarnates divine authority (the old meaning of ‘avatar’ is a deity’s incarnation on earth), the earlier Roberta might have confided the following to her new virtual counterpart: that freedom is always conditional. Technologies that promise a way to transcend bodily limitations also impose new restrictions on how to exist in the newly created world. Immaterial imaginaries are rooted in bodies that are all too material.85

As for the legacy of Thek’s hippie, Paul McCarthy’s work conceptually reincarnates the volatile effigy of The Tomb in an advanced media context. In The King 2006–11 McCarthy lent his own likeness to an enthroned and crowned silicone auto-effigy made using cutting-edge scanning and fabrication techniques. Much like Thek’s effigy, McCarthy’s king wore an incongruous blonde wing and bore signs of violence on his exposed limbs. Partially disarticulated at the joints, the figure’s arms looked as if they had been attacked with a machete, recalling perhaps the former’s severed fingers. Later in 2013 McCarthy unveiled WS, a gargantuan environment and series of video installations at the Park Avenue Armory that chronicled the debauched goings-on in the household of White Snow, a contrary Disney princess played by actress Elyse Poppers. Here McCarthy took the role of the tyrannical yet pathetic Paul Walt, an alternative Walt Disney who wears grotesque facial prostheses, gets smeared with household condiments like ketchup and chocolate sauce, and hobbles around with his pants around his ankles. Life Cast, another exhibition by McCarthy that ran simultaneously, consisted of five silicone effigies displayed on separate tables, each one naked, hyperrealist and pristinely clean. Four were made in Poppers’s likeness and depicted her sleeping and awake (fig.9). The last was a ‘dead’ McCarthy lying on a black table under a skylight.

Fig.9

Paul McCarthy

That Girl (T.G. Asleep) 2012–13

Silicone, paint, hair, wood, glass and melamine board

© Paul McCarthy

Courtesy of Hauser & Wirth, New York

WS and Life Cast both seem to return to the primal scene of Mike Kelley’s rehabilitation of Thek. At the end of his essay Kelley imagined a cryogenically frozen Walt Disney lying beside Thek’s ‘stinking hippie in permanent fixed decay – a pink raspberry shitsicle in answer to Walt’s porcelain-white vanilla bar’.86 In The King McCarthy evoked Hollywood spectacle and the surveillance state in equal measure, giving form to the sovereign’s perverse doubling of the abandoned homo sacer. In WS he thawed out the vanilla-bar sovereign and thus effectively merged a cadaverous Disney with the dirty pink hippie into one body. In the process he gave riotous life to what his former collaborator, himself now deceased and deserving of commemoration, had so memorably imagined. If these figures all represent some version of The Tomb reborn, they also belong to the lineage of The Dante Hotel, a feminist work that figures less prominently than it should in art historical accounts of polychrome effigies and their performative dimensions.87 In a way, Hershman Leeson’s wax women emerged out of the counterculture’s ruin as newfound historical subjects, forged in the after-effects of free love’s exploitation but in light of a new consciousness at the threshold of second wave feminism. Persisting well after their loss and destruction, Hershman Leeson and Thek’s counter-effigies represented contested subjectivities through volatile bodies. These intimate self-portraits of degraded archetypes were at once personalised and generic in how they presented victims of state violence and its survivors.