Until yesterday I looked for explanations. Today, all I want to do is eat and excrete things. There is no time for permanence, only for passage.

Teresinha Soares, 19711

Although Teresinha Soares was only active as an artist between 1965 and 1976, she left a lasting mark on the history of the Brazilian avant-garde. From the onset her works stood out for their distinctively erotic aesthetic, which placed her at the centre of a discussion on sexual liberation and women’s rights. Because she experimented with sculpture, printmaking, painting, installation and performance, her works often resisted easy classification and were affiliated with different tendencies including Brazilian new objectivity (because of her exploration of participative objects and environments), and erotic art (because of her references to sexuality). The visibility of Soares’s work and questions surrounding its classification have been revived by the recent interest in global pop, which has led curators and historians – most notably Jessica Morgan, Giulia Lamoni and Marília Andrés Ribeiro – to include Soares in an expanded pop canon.2 As such, Soares’s experimentation with participative objects and environments as well as her references to sexuality and popular culture have all been singled out as important characteristics of her work, while the contiguities between these various elements and her power to exceed and slip between them has been downplayed. This article will explore Soares’s relationship to new objectivity and erotic art – affiliations that were dominant at the time in which she was working – before proposing the term ‘Pantagruelian pop’ as a new way to read Soares’s work through both global and local lenses and in relation to the openness and fluidity of her practice.

Between erotic art, new objectivity and pop

In order to map out the complex influences and labels that circulated at the time, it is important to locate Soares’s practice within the wider cultural scene of the 1960s, paying particular attention to terminology. At the end of the decade Soares was working outside the dominant artistic groups and styles as well as the renowned cultural centres of São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro. As such she occupied a singular position in the Brazilian avant-garde. The ‘realistic’ themes and images presented in her work elicited controversy and were seen, in the eyes of ‘society’ – a term used in Portuguese to describe a snobbish elite – as problematic. In response to critics’ framing and categorisation of her work, Soares was awarded the title of the most widely ‘massacred’ artist in Brazil.3 Other headlines asked ‘Who’s Afraid of Teresinha Soares?’, an ironic wordplay on Walt Disney’s three little pigs song ‘Who’s Afraid of the Big Bad Wolf?’ (or perhaps Edward Albee’s 1966 play ‘Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?’, reflecting her fearlessness and disillusion).4 Critiques of her art extended to speculation and gossip about her private life and sexuality. One article by a writer and Catholic bishop outed Soares as a lesbian after misinterpreting an inscription on her installation Graves 1972 that read ‘Lettuces were planted all over me and I ate them’.5 Despite such criticisms her first solo exhibition in Belo Horizonte in 1967 at the Guignard Gallery attracted so many people that the street had to be closed off. Frederico Morais, the esteemed critic, artist and one of Soares’s first professors, stated in the text introducing the exhibition: ‘She produces as if possessed by the devil’.6 Among the works on paper she exhibited was a series of silkscreens, collectively titled A Man and a Woman 1967, which depicted in red, yellow, black and green intertwined male and female figures made up of fragmented profiles, breasts, hearts and embracing limbs (fig.1).

Fig.1

Teresinha Soares

From A Man and a Woman, Homage to Claude Lelouch, Director of the film Un Homme et une Femme 1967

Silkscreen on paper

33 x 41 cm

© Teresinha Soares

Fig.2

Teresinha Soares

A Box to Make Love In 1967

Painted wooden box, meat mincer, stuffed fabric heart, bottle of dragon Vaseline and rubber tubes

© Teresinha Soares

Photo: Miguel Aun 2011

The first tendency Soares was largely associated with was Brazilian new objectivity, a term consolidated after an exhibition of the same name held at the Museum of Modern Art in Rio de Janeiro (MAM-RJ) in April 1967. The exhibition was largely driven by Hélio Oiticica and other Rio-based artists and critics, and proposed new objectivity as a gathering together of various Brazilian avant-garde tendencies primarily around the emergence of new forms distinct from painting and sculpture. Many of the key proponents of this style lived and worked in either Rio or São Paulo and it was in these contexts that Soares was exposed to this work, and in turn that her work was positioned in relation to it. In 1967 Soares moved for a period to Rio in order to participate in the famous workshop led by printmaker Ivan Serpa at the Museum of Modern Art. There she met artists Rubens Gerchman, Anna Maria Maiolino, Antonio Dias and others. Although Soares never participated in group activities in close connection with other artists, she did exhibit with them. For instance in the group exhibition Box-Form, held at Rio de Janeiro’s Galerie Petite, Soares presented one of her earliest sculptures in wood titled A Box to Make Love In 1967 (fig.2). The exhibition, considered a vital precursor of Brazilian New Objectivity, gathered the works of artists that were working with wooden ‘boxes’, including Gerchman and Oiticica.7 A Box to Make Love In, one of the very few surviving sculptures, is a wooden cube painted in green, red and yellow, with two faces intertwined in the shape of a heart above it, and a whole mechanical apparatus within it equipped with a meat mincer that viewers could operate. The box was fitted with a bottle of Dragon Vaseline and a stuffed fabric heart; its call to interact aligned Soares’s formal concerns to those of the avant-garde in Rio and São Paulo. This early sculpture and its exhibition demonstrates how Soares’s art was not only considered in relation to new objectivity but contributed to its definition.

Fig.3

Teresinha Soares

Deadly Sins, from Edit of Virgin Films 1968

Paint on plywood

© Teresinha Soares

In the catalogue of Soares’s first solo exhibition in São Paulo, held at the Art-Art Gallery in 1968, Mário Schenberg stated: ‘Her works fully draw from art’s fundamental objective: live communication’,8 and added that she was ‘one of the most interesting personalities tied to New Objectivity’.9 This comment points to his appreciation of Soares’s ability to maintain the formal language of new objectivity while approaching themes as sensitive as sexuality, eroticism and love. Among the works she exhibited were a series of drawings and wall pieces, Edit of Virgin Films 1968, and a floor piece titled Roberto Carlos, Sing for Us 1968, a tribute to the iconic pop rock singer, songwriter and actor, also known as ‘The King’ after his own idols Elvis Presley and the footballer Pelè. The Edit of Virgin Films paintings, which are made to resemble strips of film, examine cultural perceptions of women and the fetishisation of the female body in cinema, television, advertising and pornography. One work from the series, titled Deadly Sins (fig.3), represents the sins of gluttony, lust and envy, featuring three frames containing images of red lips, exposed breasts, and a male profile observing the torso of a naked woman. The bodies are only partially represented and cut off by the heavy borders between each frame. Like her use of the box as a form that both contains and restricts the love of the couple in A Box to Make Love In, here framing structures another encounter between intimacy and alienation. In addition it reflects the alienating effect produced by the media, a theme that reappears in her work (especially in relation to images of the war in Vietnam) and which suggests a connection with a pop sensibility.10 This series – the collective and individual titles of which refer to Christian beliefs and stories – was the first body of work in which Soares alluded to religion and therefore just as it gestured to an emerging international image culture, it also related to the particular Catholic context of Brazil. The state of Minas Gerais in southern Brazil, where Soares was born, is still considered one of the most traditional and Catholic in the country, and so by incorporating religious references in a work about sex Soares did the unspeakable for a woman of her provenance. Yet the idiosyncratic relationship between the sacred and profane has the effect of parody, which markedly lightens the overall tone of the work.

Roberto Carlos, Sing for Us is also explicitly connected to Christianity. The work consisted of a three-metre long rosary made of plywood cut-outs, each bead replaced with a hat, an umbrella, a shoe, and other traces of a crowd. Instead of picturing the crucified image of Jesus Christ, the cross shows fragmented images of the body of Roberto Carlos: in the centre his lips singing, then his hands holding a microphone, on the bottom the images of naked feet, intertwined, perhaps in the act of making love. The whole piece was placed around a red heart-shaped pillow on which viewers could rest, perhaps a space for the religious contemplation of ‘The King’.11

In 1967 Soares also participated in the ninth São Paulo Biennial, which showcased – for the first time in Brazil – the work of twenty-one New York pop artists alongside a significant amount of figurative art from both eastern and western Europe. This exhibition marked the moment when the term ‘pop’ started to make its way into the local idiom. The Brazilian contribution to the exhibition featured the work of over 390 artists, and was seen as a corollary to the Brazilian New Objectivity exhibition as it included diverse avant-garde practices including neo-concretism, Popcreto (a term coined by concrete poet Augusto de Campos), nouveau réalisme and magic realism. Although Oiticica had explicitly differentiated new objectivity from pop, as well as op art, hard-edge and nouveau réalisme, the term ‘pop’ was nonetheless picked up by discontented critics.12 The critic and curator Aracy Amaral, for instance, condemned the younger generation’s willingness to embrace an ‘American way of living’ at the cost of sacrificing their ‘Brazilian reality’.13 The hostility towards pop was the result of an anxiety towards North American cultural imperialism, heightened by the United States’ support of the military dictatorship, which has been in place since the coup d’etat of 1964.14 Regardless of pop’s professed affiliation to the United States, the term appeared increasingly in the press, and a ‘pop influence’ was soon perceived in Soares’s works.15 Already in April 1968 she participated in the exhibition The Brazilian Artist and Mass Iconography organised by Morais at the Faculdade de Desenho Industrial in Rio de Janeiro. The show prompted an in-depth analysis of the impact the mass media was having on Brazilian artistic production, establishing further connections with pop.

After 1968 the violence increasingly perpetrated by the military regime led many artists in Brazil to call for an international boycott of the state-sponsored biennial and rally support from artists and intellectuals worldwide. Although Soares opposed the boycott, which she saw as a nihilistic act of compliance, during a panel discussion at the eleventh biennial in 1971 she claimed her practice as ‘an erotic art of contestation’.16 Her works had steadily become more politicised since the exhibition From Body to Earth in 1970, also organised by Morais. The exhibition’s premise – as discussed by Morais in recent texts – was to examine and redefine the role of the art object in the Brazilian avant-garde beyond the definition of object-as-category achieved in 1967 when Brazilian New Objectivity was inaugurated in Rio de Janeiro.17 Morais’s ideas concerning contemporary production in Brazil were also expressed in an article titled ‘Against an Affluent Art: The Body is the Work’s Engine’, in which he provided the definition of a new ‘guerrilla art’.18 This, he argued, celebrated an art of enunciation, of liberation and of self-assertion, especially following the enforcement of the infamous Institutional Act No.5, which had reduced the powers of Congress, enhanced censorship measures, abolished the habeas corpus, and legalised torture. In the statement, which was printed on a flier and distributed all over the city, Morais set the tone for the exhibition:

From art to anti-art, from modern to post-modern, from avant-garde art to counter-art, the opening is always greater. Art’s horizon today is open, yet inaccurate. Situations, events, rituals or celebrations – art cannot be distinguished clearly from either life or the everyday … The life that pulses within your body – that is art. Your environment – that is art. The psychophysical rhythms – that is art. Intrauterine life – that is art.19

Fig.4

Teresinha Soares

She Hit on Me (BEDS) 1970

Painted wooden bed frames, wooden panels and mattresses

© Teresinha Soares

Fig.5

Teresinha Soares with She Hit on Me (BEDS) installed at Municipal Park, Belo Horizonte, 1970

© Teresinha Soares

Morais saw art as a situation, a ritual, ultimately a weapon, and artists as guerrillas. A firm supporter of Soares from their time in Belo Horizonte in 1965 when he wrote introductory texts for her exhibitions, Morais thought of her as an advocate for women, using her own body as a weapon of contestation.20 In From Body to Earth Soares exhibited the work She Hit on Me (BEDS) 1970, consisting of three modular wooden beds laid on the gallery floor, which the spectator could lounge on and enjoy (figs.4 and 5).21 Each mattress was painted in the colours of a Brazilian football team (National, Flamengo or Clube Atletico Mineiro) and each bed frame was adorned with hinged shutters carved to trace the outlines of provocatively posed nude female bodies when they were closed. On the reverse of the shutters Soares painted the portraits of footballers Pelé, Yustrich and Tostão in a vibrant pop palette. In an interview about this work Soares stated: ‘There are those who put people to bed. I put beds in art’.22 Soares’s beds provided space for encounters: literally, as viewers could meet there; symbolically, in the representations of masculinity and femininity; and politically, through the coming together of national identity (the football teams and players) and the intimate domestic realm conveyed by the beds.23

Fig.6

Page from the album Eurótica 1970

Silkscreen on paper

© Teresinha Soares

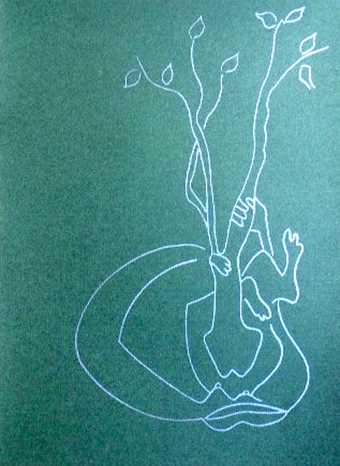

The content of She Hit on Me (BEDS) alludes to another key context of Soares’s practice: erotic art. The text in which the definition of erotic art appears most evidently is an introduction by Morais to an album of silkscreens titled Eurótica (a wordplay between the Portuguese ‘eu’, meaning ‘I’ and ‘erotica’, which Soares combined to infer ‘eroticism is mine’). The album, which became known as the ‘Brazilian Kamasutra’, comprises a series of single line drawings, beginning with images of sexual acts between men and women, phalluses, breasts and limbs discernible.24 Over subsequent pages the male and female figures reach a climax and the images go on to depict encounters between multiple figures, women with women, men with men, until finally the silhouette of a horse intertwined with a woman appears. The final image in the album shows a pair of legs spread, from which a phallus shape emerges and then transforms into a tree, a symbolic image of growth, birth, fertility and an example of eroticism extending into human relationships with the surrounding world (fig.6). In the associated text Morais interpreted Soares’s work as a communion between sexes and praised the freedom with which it reflected both an avant-garde attitude in art and an avant-garde attitude towards sex. Morais relied heavily on philosopher Herbert Marcuse’s Eros and Civilization (1955) – an important text for contemporary counter-cultural movements, particularly around the development of ‘free love’ – to explain the necessity of releasing sexual inhibition in order to retrieve a sense of wholeness lost with the ‘excessive sense of spatialisation … a result of the social division of labour and industrial revolution’.25 He also quoted from Phyllis and Eberhard Kronhausen’s international exhibition of erotic art, first launched in 1968, to argue that sexual freedom cannot exist without political and economic freedom:

Erotic art expresses a vital freedom of individual happiness and mental well-being but a sexual freedom cannot exist without a high degree of political and economic freedom. In this sense, the erotic art conveys a real revolutionary message. It requires an extension of freedom not only in the sexual domain, but also in every sphere of social life.26

Fig.7

Teresinha Soares

Body to Body in Colour-Pus of Mine 1970

© Teresinha Soares

The album Eurótica was exhibited alongside an installation and performance titled Body to Body in Colour-Pus of Mine 1970 at Rio’s Galeria Petite in 1971.27 The sculptural element of the piece was a multi-modular assemblage of white wooden platforms of differing levels over a surface area of twenty-four square metres (fig.7). Observed from an elevated standpoint, the modules reproduced the shapes of naked silhouettes and male phallic forms. Exhibition visitors were also invited to take off their shoes and inhabit the installation. Its labyrinthine structure provided another space for surprising encounters between those circulating its organic shapes. During the happening, which occurred at the exhibition’s opening, Soares instructed three performers dressed in black (two women and a man), to dance over the work, enacting love-making between each other and the structure itself. Images of cells splitting and multiplying were also projected over the entire installation, while Soares, from the side-lines, read a text by a renowned scientist on the life of sperm from birth until death, which she interjected with a poem she had written:

I’m soiled flesh

dry-contorted

exposed-exhausted

suffered

I’m a bare island

enclosed

by people

silent, frozen

I am what I am

a toy

playful

anything

taking up space

finished

void

lost

I’m shadow at night

light at day

I’m what I was

not before

to then become

that

which happened after.28

The fragments of text in Soares’s poem convey a sense of destruction followed by renewal: the imagery of beaten, soiled, flesh and of shadow versus light conveys a vision of destruction or defeat. The final verse ‘which happened after’, indicates the presence of a future, one that is still uncertain, a symptom of continuation, and perhaps renewal, rebirth, symbolised within the passage from darkness to light: ‘I am shadow by night, light by day’. In addition, the collaboration of men and women in the performance, combined with the imagery of the installation, heightened notions of union and encounter. The sculptural elements of Body to Body in Colour-Pus of Mine were the linear silhouettes in Eurotica rendered in three-dimensions. In this way the interactivity of the platforms, combined with the performance, complemented the notion of encounter and separation manifested in the drawings. Soares’s poem also echoes the final message of renewal of rebirth suggested by the album’s final page where the body in effect disintegrates in nature, allowing for its rebirth.

In different ways, then, Soares’s work had ties to numerous contemporary artistic tendencies and practices. New objectivity heightened the formal aspects of her work, the new materials and techniques she engaged with, and the increasing importance attributed to spectator participation. Her investigation of objecthood and use of popular culture references, whether appropriated from the mass media or assimilated through local customs, meant her work was included in important exhibitions and, in the case of the São Paulo Biennial, on an international stage. Meanwhile, Soares’s own concern for an ‘erotic art of contestation’, and Morais’s exposition of this, situated her art in relation to sexual liberation and freedom of expression, where the boundaries between sex and politics blurred, challenging the military regime’s oppressive methods. These labels serve to reiterate Soares’s position as a Brazilian artist, yet it is also possible to read her work within an international context, especially given the recent expansion of terms such as ‘pop’ away from an Anglo-American focus. In one sense this reflects the contemporary concern with globalisation, but it also foregrounds the links between the present day and the proliferation of commercial culture in the 1960s. It is this context that pop is uniquely placed to describe. Ever since its canonisation in the critic Lucy Lippard’s 1966 book Pop Art, pop has rendered itself ambiguous, resisting any concise categorical definition.29 But it is precisely this ambiguous quality that has prompted productive discussion of pop’s origins and history. Pop art is not self-contained but reflects its surrounding spaces. The potential of pop as a category is thus not about enclosing art, but about revealing the cultural flow across a decade.

The reason for pop’s ubiquity on an international scale in the 1960s might be seen as a process of homogenisation. However, the term itself had currency at the time, as critics often adjoined adjectives, suffixes or neologisms to foreign terminologies to explain local iterations. This was certainly the case in Brazil, where the celebrated critic and firm supporter of Brazilian new objectivity, Mário Pedrosa, coined the descriptor ‘Popistas of Underdevelopment’ to describe the works of Rubens Gerchman and Antônio Dias in relation to the most celebrated pop artists.30 This controversial expression addressed the basic incongruences between Brazilian pop and American pop in light of the differing relationship with capitalism and consumption.31 In a similar vein the poet Décio Pignatari used the term popau, a combination of pop and pau, meaning wood, which makes reference to the ‘Pau-Brasil Manifesto’ (1924) by Oswald de Andrade. This text preceded de Andrade’s more well-known ‘Anthropophagic Manifesto’ in describing Brazilian culture as cannibalistic, devouring and digesting international styles and currents.32 Seen in this way pop has a particular resonance for understanding Soares’s work, not only because she referenced mass media and popular culture in her art, but also because her work evaded any single classification and itself sought to establish sites for the flow of bodies, as well as cultural and social referents, connection and disconnection. The particularity of this aspect of Soares’s work can be emphasised not by reading it as straightforwardly ‘pop’, but by thinking of it through the term ‘Pantagruelian’. This word derives from Russian theorist Mikhail Bakhtin’s re-reading of François Rabelais’s Renaissance novel Gargantua and Pantagruel (1532). Invoking the tensions between the ‘folk culture of humour’ and the ‘bourgeois conception of the completed atomised being’, it is used here to trace a more nuanced understanding of the Brazilian pop moment and the tension between newer imported culture versus vernacular traditions.33

Why Pantagruelian?

Pantagruelian is a synonym of enormous and comes from the name of one of the protagonists in Rabelais’s tale of two giants, Gargantua (the father) and Pantagruel (the son). Peppered with vernacular language, crude narrations and obscene imagery, the novel was deemed indecent at the time of its publication and was never included among the great works of the Renaissance, despite the fact that authors of the calibre of Voltaire, François-René Chateaubriand and Victor Hugo thought Rabelais to be one of the ‘greatest geniuses of humanity’.34 In the late 1930s Bakhtin wrote the celebrated book Rabelais and his World (first published in 1965) in which he re-examined the value of this novel, crediting its use of carnival or marketplace culture to portray the transition from medieval to Renaissance society. Soares’s practice shares many of the concepts and characteristics identified by Bakhtin in Rabelais’s novel, especially those of heteroglossia, the carnivalesque and grotesque realism.35

Bakhtin used the term ‘heteroglossia’ to describe a form of language used by novelists whereby the speech habits of the bourgeoisie are interwoven with those of the wider population to achieve a truly representative form of expression. Bakhtin wrote:

Languages of heteroglossia, like mirrors that face each other, each of which in its own way reflects a little piece, a tiny corner of the world, force us to guess at and grasp behind their inter-reflecting aspects for a world that is broader, more multi-levelled and multi-horizoned than would be available to one language, one mirror.36

Soares’s appropriation and combination of popular culture, religious and artistic references in her artworks might be considered utopian when seen through Bakhtin’s heterglossia. The reflection of a ‘multi-levelled’ world suggests the ability to represent a broad and diverse society rather than simply the interests of the bourgeoisie. This was an ambition shared among artists in Brazil although historians such as Marta Traba and Aracy Amaral have interpreted this objective as ‘vain rhetoric’ in light of the fact that most artists belonged to the middle class minority and were isolated from other social groups.37 In fact Soares acted as a kind of mediator between the interests of a broader population and the elite, who she never denied belonging to, but who were nonetheless outraged by her boldness.

For Bakhtin ‘the carnivalesque’ referred to the carnival as a social institution, in which no social divisions existed and ‘all men are equal’.38 In this circumstance the official state – symbolic of rigid and sterile social paradigms – is placed in opposition to a more popular culture comprised of a form ‘of protocol and ritual based on laughter and consecrated by tradition’.39 During carnival everyone is allowed into ‘the utopian realm of community, freedom, equality and abundance’.40 Of course the carnivalesque has a particularly strong relationship to Brazil, as is evidenced by wearable works of art such as Oiticica’s Parangoles from the mid-1960s. The Parangoles were first worn by the dancers of the Mangueira Samba School from a favela in Rio de Janeiro during the 1966 carnival. Soares’s interest in football, celebrity culture and religion open her works to collective spectacle and play. Indeed her strategic use of hyperbole, in the form of enhanced breasts and phalluses or the dramatic portraits of footballers in action, suggest an affinity with the satirical side of carnival whereby the excesses of popular culture overwhelm and undermine the strictures associated with high culture.

Bakhtin recognised hyperbole as a vital component of carnival traditions, where exaggerated features, colours, costumes and behaviour provide a break from the everyday. These elements were in turn harnessed in Bakhtin’s definition of ‘grotesque realism’, a literary mode epitomised by the reversal of the commonplace. Based on parody, humiliation, exaggeration, travesties and profanations, the humour of grotesque realism is never only positive; instead it embraces ambivalence, being at once joyful, triumphant, mocking and deriding. One of Bakhtin’s key conclusions from his analysis of the carnivalesque and grotesque realism is that the body is the basis of our social constructs and of our relationship with our environment:

The body and bodily life have here a cosmic and at the same time an all-people’s character; this is not the body and its physiology in the modern sense of these words, because it is not individualised. The material bodily principle is contained not in the biological individual, not in the bourgeois ego, but in the people, a people who are continually growing and renewed. This is why all that is bodily becomes grandiose, exaggerated, immensurable.41

Bakhtin referred to the reproductive organs, the womb and the belly as the ‘lower stratum’ of the body or the ‘bodily grave’, the grotesque body.42 An emphasis is placed on open orifices and penetrative appendages (nose, penis), which facilitate an exchange between the body and its outer world through sex, eating and excreting.

Soares’s affinity with the grotesque body – with excess and rebellion – was expressed in the remark made in 1971 with which this essay began, but it is also evident in her use of the body in her art. Bodies are depicted in exposed or intimate moments, but without recourse to shame. The explicit imagery contained in Eurótica reveal something of Soares’s sexual phantasies with complete earnestness and honesty. In this way Soares’s work, as Morais also suggested, evacuates shame as a means to surpass the trauma of political, social, and sexual repression.43 The clunkiness and clumsiness of some of her figures, as well as her interpolation of visitor’s bodies into her installations, might also be read as Bakhtinian. They are exemplars of the ‘degradation’ inherent to carnival, bringing down to earth what is abstract and spiritual. Yet degradation is a death and a rebirth at the same time because of the productive and regenerative power of the earth and the body. The earth swallows death but returns life. The final page of Eurótica further exemplifies this cycle with the image of the ‘lower stratum’ becoming absorbed by nature and flowering into something new. This imagery is also reflected in Soares’s poem which accompanied Body to Body in Colour-Pus of Mine, where the passage of her body from darkness to light invokes a process of degradation followed by one of regeneration.

By uniting pop with the concept of the ‘Pantagruelian’ many of the themes present in Teresinha Soares’s work have been woven into a narrative of cultural metamorphosis and renewal. As Bakhtin sought to shed light on the shifts that characterised the progression from the Middle Ages to the Renaissance he became caught in the Second World War, which is why his study was not published until 1965, the historical epicentre of this investigation. Pop allows us to retrieve works of art that represent the 1960s as an epoch of transition, evident in the consolidation of capitalism or in processes of sexual liberation.

Soares’s work grappled with the immodest themes of sex, religiosity and politics, indexing the abrupt changes in Brazilian culture. Her works also prompt discussion of the largely understudied field of women’s art in Brazil.44 Among her contemporaries working within the pop idiom were Lotus Lobo, who created large scale lithographs reproducing the labels and packaging of commercial goods; Wanda Pimentel, whose depictions of domestic scenes feature isolated elements of her body; and Anna Maria Maiolino, who in the context of new objectivity created three-dimensional body parts (an ear, the digestive system, a mouth), which examined the effects of consumption on the body. Although there has not been space to discuss the work of these artists in relation to the term ‘Pantagruelian’, it has proved useful in revealing aspects of Soares’s engagement with Brazilian culture at large, and may also be relevant to the work of others. Most importantly, however, and true to Soares’s outlook, this discussion has sought to draw attention to the outrageous excess of her work and to demonstrate her ability to transcend definition.