The Belgrade painter Dušan Otašević was eighteen years old when the market economy was first introduced to post-revolutionary Yugoslavia in 1958. That year, the 7th Congress of the Communist Party of Yugoslavia addressed not only the organisation of production within a rapidly growing economy, but, for the first time, the question of consumption, considering it to be a marker of social development. The Congress identified a ‘more comfortable life’ as a political goal, to be achieved through ‘better service provided to consumers’, ‘individual ownership over consumer goods’ and increased care shown towards ‘everyday needs, leisure and entertainment’.1 The late 1950s in Yugoslavia were marked by unprecedented economic growth, the significant improvement of political, cultural and economic relations with western European countries and the United States (as well as with the USSR after Stalin’s death), the development of an entertainment industry (especially commercial cinema and popular music), and an overall emphasis on social modernisation, evidenced by the official support shown towards modernist art.2

By the time Otašević graduated from the Belgrade Art Academy in 1965, academic discourse on art based on symbolism and post-cubist tendencies had been replaced by more radical artistic conceptions of modernity, with ties to Russian constructivism, dada and surrealism, as well as local avant-garde traditions, primarily the zenithism of Ljubomir Micić. Whereas in Zagreb in the early 1950s the more radical artistic practices were influenced primarily by forms of constructivism (exemplified by EXAT 51 and, later into the 1960s, by the New Tendencies movement), in Belgrade the influence of surrealism was much more pronounced, for two reasons. Firstly, some of the most prominent members of the communist political elite had been surrealist poets and intellectuals who, in the 1930s, shared the political views of surrealists such as André Breton and, especially, Louis Aragon. For example, the poets Marko Ristić and Aleksandar Vučo occupied highly influential positions in the Yugoslav federation, the former as the President of the Committee for International Cultural Relations, and the latter as the President of the Committee for Cinematography. Secondly, surrealism laid the groundwork for the likes of Leonid Šejka, Ljuba Popović and Radomir Damnjan, Belgrade artists whose work of the late 1950s offered a critique of the official modernist standardisation of academic art (so-called ‘socialist aestheticism’), and for filmmakers, most notably the highly acclaimed director Dušan Makavejev, whose first amateur films were inspired by surrealism.3

The double-sided influence of surrealism suggests that the usual distinction between official culture and dissident culture in Yugoslavia is untenable. Indeed, dialogue between policy makers and practising artists was not unusual; sometimes this led to a conformist compromise, sometimes to active critical debate. One of the most striking examples of such dialogue was initiated by the increasing visibility of American culture in Yugoslavia during the 1950s. Within artistic circles this was associated with the rise of pop art, to which hostility was shown both by official policy makers (who were not so much ideologically anti-American as culturally anti-American) and by artists and critics, who identified American pop art to be symptomatic of the de-humanised denigration of art in the aggressively commercial, consumerist culture of the West.

Otašević’s work of the 1960s is now recognised as a specific Yugoslav variant of pop art, yet mainstream art criticism in Belgrade originally filed Otašević under the category ‘new figuration’, the name given to the work of European artists who apparently responded to the perceived frivolity and lack of criticality of American pop art.4 This is despite the fact that on many occasions Otašević himself articulated his acceptance of the ‘strong wind from America which blows through slumbering Europe’.5 Similarly, the art critic Slobodan Ristić noted that Otašević’s work did not fit easily within European new figuration because the style of his work and his choice of subjects were much closer to American pop art.6 Ristić also admitted the difficulty of identifying ‘what in Otašević’s works is irony, what a covert revolt, a world of objects or a neutral approach to art which has no illusions about it’, and this shows ‘a specific attempt, unknown in our art milieu at the beginning of his artistic activities’.7

American pop art was met with almost unanimous resistance from the artistic establishment in Belgrade when it arrived in Yugoslavia in the 1960s. This resistance stemmed in large part from the anti-Americanism of European high culture, and stifled the development of an adequate discursive framework for examining such art.8 This was exacerbated by Yugoslav perceptions of the highly industrialised American culture of the 1960s; pop art was considered almost spectral, its imagery phantasmal, rather than directly representing material reality. As a result there are only a few references to pop art in Serbia in the 1960s, and the same is true of other Yugoslav and central European countries. Otašević’s works from this period are rare examples of a convergence between Yugoslav modernism and pop.9

However, as much as it is crucial to recognise the similarities between Otašević’s work and American pop art of the 1960s, it is perhaps even more important to identify the politically and culturally specific aspects of Otašević’s visual language. Indeed, the lessons that Otašević learned from American pop art were applied to and directed at his immediate social and artistic contexts.

The everyday object

Serbian art education of the 1960s still relied upon traditional formal strictures, especially in the conservative milieu of the Belgrade Art Academy. According to the artist, one of these formal dogmas (based mostly on Parisian modernism from the end of the nineteenth century, and the work of artists like Pierre Bonnard and Edouard Vuillard) was that pure colours should not be placed side by side on the canvas – a practice denigrated as mere ‘painting of the flag’.10 Otašević broke this rule by actually painting a flag and consequently abandoning painterly techniques like gradation and soft modulation, and the effects of pathos and expression. For Otašević, if a painter abandoned expressiveness and gesture in the application of paint, then he could step down from the pedestal of singularity and genius and associate with the wall-painter, dyer, or sign painter: ‘It may have been inappropriate to paint a flag under the roof of the Academy, but life itself was offering only the flag. That relationship defined my affinity for the sign-painter’s methods and car lacquer sprays’.11

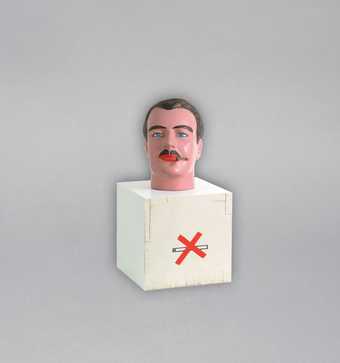

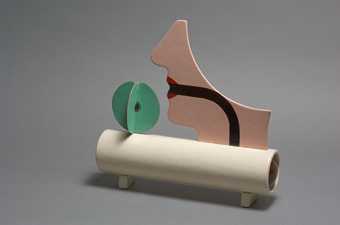

Fig.1

Dušan Otašević

Smoker 1965

Galerija likovnih umjetnosti, Osijek

© Dušan Otašević

Courtesy the artist and Galerija likovnih umjetnosti, Osijek

While American pop art evolved in relation to the media-consumer order of developed capitalism – the iconography of mass culture, the development of technology, the changes in everyday life that came with new household appliances, as well as new representations of the body and sexuality – Otašević’s works referenced the more naive and austere circumstances of an emerging consumerism in a socialist socio-economic state. This was evident in the artist’s fascination with the clumsily painted and written signs of the limited private businesses permitted in socialist Yugoslavia (bakeries, pastry shops, barber shops and so on). For Otašević, these signs represented the convergence between a desired consumer-scene and early, visual-textual attempts at realising it. The imaginarium of mass and consumer culture, concomitant with developed capitalism, was in this context, Otašević observed, imbued with the naiveté of Yugoslav undeveloped modernisation and provincialism. Far from inaugurating a new type of ‘artist-consumer’, Otašević maintained his interest in elementary modes of craftsmanship and traced their encounter with a consumer culture which had arrived from a different political and economic system.12 In the 1960s Yugoslav consumerism was still in its early stages and its forms of consumption were rudimentary, something the motifs in Otašević’s works reflect. To be a consumer in the public field meant to go out nicely dressed for a stroll on the corso, to eat an ice cream and drink a lemonade in the pastry shop, or to smoke a cigarette in front of a cinema after watching a movie in which, as Otašević said, ‘all heroes smoked’.13

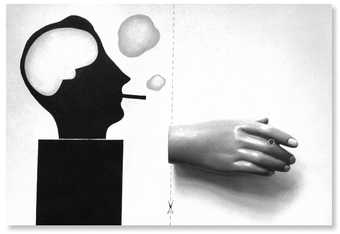

Fig.2

Dušan Otašević

Smoker II 1965

Private collection

© Dušan Otašević

Courtesy the artist and private collection

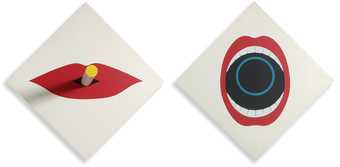

In a photograph taken at first solo show, held in the gallery of the Atelje 212 theatre in Belgrade in 1965, Otašević is seated with a cigarette in his mouth, surrounded by four of his ‘smoking works’. The first, Smoker 1965 (fig.1), comprises the head of a shop-window dummy with a mounted cigarette on a stand showing the sign for ‘no smoking’; Smoker II 1965 (fig.2) is the profile of a ‘smoker’ on board, with the dummy hand-mounted alongside; Obelisk 1965 is an enlarged matchstick made from wood and plaster, and Cigar 1965 (fig.3) is a diptych consisting of a schematic image of lips with a wooden cigarette and an image of an open mouth with a bluish circle inside. In a self-reflexive gesture, the artist plays the part of popular hero, becoming Jean-Paul Belmondo in Jean-Luc Godard’s Breathless (1960), an actor who became emblematic of this kind of figure, shaping an imaginary encounter between everyday life and popular fiction.

Fig.3 Dušan Otašević

Cigar 1965, remade 2003

Collection of Slavica and Daniel Trajković

© Dušan Otašević

Courtesy the artist and Slavica and Daniel Trajković

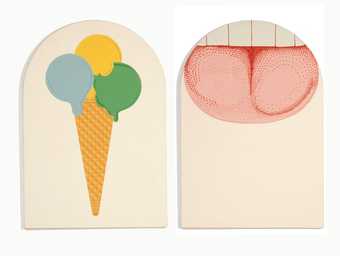

With the sign paintings and the smoking works in mind, it is clear that Otašević was interested in consumer goods and iconic personalities – two ‘topics’ seemingly consistent with pop. Yet instead of branded products, Otašević’s consumer goods were simple and generic: along with the aforementioned Smoker and Cigar from 1965, Yes Sir! 1966 (fig.4) depicts an ice-cream cone with ice-cream scoops in different colours alongside a large open mouth, and Cakes 1967 represents a piece of chocolate cake or whipped-cream rolls. Moreover, Otašević’s pop icons related more closely to the context of revolutionary socialism than to Western pop culture: Lenin in Towards Communism Follow Lenin’s Course 1967, Tito in Comrade Tito, Our Violet White, the Young Adore You as Their Light 1969 (fig.5) or Mao in Mao Tse Swims to Communism 1966. While some interpretations have read such works as exclusively ironic – that is, as ironic reproductions of communist iconography – it may be more appropriate to read them as ambivalent.14

Fig.4

Dušan Otašević

Yes Sir! 1966

Collection of Slavica and Daniel Trajković

© Dušan Otašević

Courtesy the artist and Slavica and Daniel Trajković

Fig.5

Dušan Otašević

Comrade Tito, Our Violet White, the Young Adore You as Their Light 1969

Museum of Contemporary Art, Belgrade

© Dušan Otašević

Courtesy the artist and Museum of Contemporary Art, Belgrade

Comrade Tito, Our Violet White… is particularly emblematic of this ambivalence, and unique in the context of Yugoslav art of the time. Otašević exhibited it after completing his obligatory military service, during which his skills as an artist were drawn upon (a theme also explored in Sentry Box 1969). The work consists of a portrait of President Tito painted on a panel, with the party and state flags either side rendered in corrugated painted aluminium and the five-pointed star, made from wooden slats above. The whole composition sits on a heart-shaped panel with a repetitive flower motif, reminiscent of kitsch wallpaper. The portrait is based on two photographs from the National Liberation War – one from a German ‘wanted’ circular and the other which shows Tito in a Marshall’s uniform – although Otašević used bright, cartoon-like shading. The form of this wall arrangement corresponds to the scenography of socialist festivals, such as the May Day parade, party congresses and cultural performances in factories or schools. In this work Otašević renders Titoism as a kind of DIY-pop, visualising the relationship between politics ‘from above’ and its iconisation ‘from below’.15

If we temporarily put aside the difference in economic and political systems, as well as the simplistic contention that pop art was not possible in socialist block countries, significant similarities can be identified between Otašević’s work and that of several seminal pop artists (although it is difficult to determine whether Otašević had any knowledge of actual works at that time).16 There is some overlap, for instance, with Peter Blake, particularly The First Real Target 1961 (Tate T03419), as both artists use household paint to confront painterly style, and blur the distinction between the real object and the artwork. His painted wooden objects also bear resemblance to the reliefs of another British artist, Joe Tilson (for example, Wood Relief No.17 1961, Tate T00480). Connections can also be made with the work of major American pop artists such as Roy Lichtenstein, especially his use of comic book imagery, and Andy Warhol, given his interest in consumer procedures. Otašević’s fascination with sign painting relates to the work of Robert Indiana, and his blow-up method to that of Claes Oldenburg. Likewise the ‘home-made look’ of Otašević’s work, with its references to tools, is also characteristic of some of Jim Dine’s works, with both artists insisting on bringing art into a ‘direct relationship with everyday experiences by identifying an object not by means of its painted simulation but by the form of the object as such’.17

Fig.6

Dušan Otašević

Polyptych 1966

Museum of Contemporary Art, Belgrade

© Dušan Otašević

Courtesy the artist and Museum of Contemporary Art, Belgrade

Despite the lack of evidence concerning actual cross-pollination between artists, similarities in both form and content confirm not only the effects of cultural internationalism after the Second World War but also the fact that in Yugoslavia industrial progress and increased consumption had a specific local impact. For instance, although Otašević’s Obelisk 1965 – a two-metre high wood and plaster ‘blow-up’ of a matchstick – was not made in response to Oldenburg (whose sculptures became more widely known only in the second half of the 1960s), the works are certainly comparable in the way they relate art to consumer goods. Of course, there is also a major distinction to be made: Oldenburg worked in a commercial artistic system, his work further estranging an object by enlarging it, which was not quite the case with Otašević’s Obelisk. The matchstick, symbolic of the ephemerality of an object in everyday use, appears again in Polyptych 1966 (fig.6). This four-panel painting may also be compared with the work of Lichtenstein and Warhol; the comic-strip seriality of the four frames presents a diagrammatic narrative of the matchstick as it burns, moving from yellow sparks to red heat to withered black char.

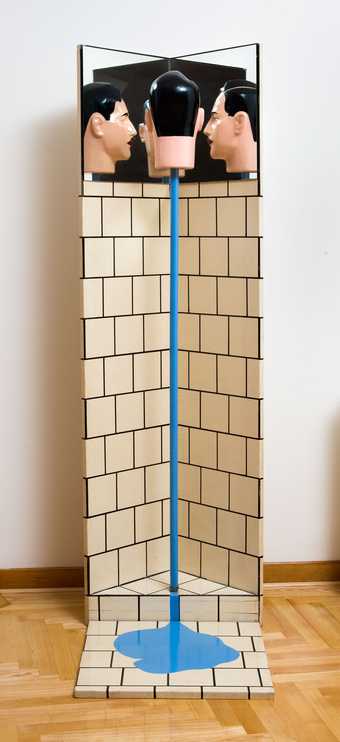

Fig.7

Dušan Otašević

Pissing Happily or Blue Flux Flooding 1966

Collection of Slavica and Daniel Trajković

© Dušan Otašević

Courtesy the artist and Slavica and Daniel Trajković

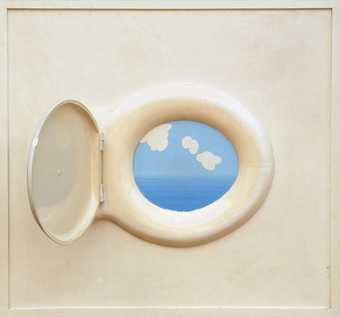

In a similar way, works from Otašević’s ‘bathroom’ series, such as Cleanness is One Half of your Health, Uncleanness the Other 1967 and White as Snow, Otašević’s Show 1969, seem like typical pop art polyptychs. However, their focus is primarily on the relation between an object and its making and on materialising an action which is vernacular, everyday and corporeal, like brushing teeth or shaving. In another work from this series, Pissing Happily or Blue Flux Flooding 1966 (fig.7), the head of a male department store dummy (reflected in a mirror) is mounted on a blue pole at the bottom of which sits of pool of blue paint spilling over ceramic tiles.18 The pole represents a stream of urine, referred to in the title, which stands in for the body, reducing it to a single function. Another work, Sea! Sea! 1966 (fig.8), consists of a painted wooden toilet seat. When the lid is lifted, instead of a watery or fecal abyss, one sees an image of the sea and sky dotted with white clouds. In these works the legacy of surrealist tropes is especially notable, as are the early films of Dušan Makavejev, mentioned above. Shop windows, mannequins, mirrors, the ‘lowness’ of body fluids and the uncanny relation between the animate and inanimate are all themes shared by Otašević and the surrealists.19 So too is the exploration of the relationship between commodities, the unconscious, politics and sexuality. Otašević’s work also performs libidinal humour, although one more specific to the socio-economic context of socialism. For Freud, jokes were an outlet of the subconscious, occurring when the conscious mind is allowed to express subconscious content that society openly or latently suppresses or deems inappropriate.20 Jokes are therefore related to both the unconscious and the political.

Yet the humour in these works is not solely the result of a joke. What is comic in Otašević’s works is the foundation of humour itself, particularly as understood through French philosopher Henri Bergson’s concept of ‘non-conformity’ or, in the mid-1960s, by writer Arthur Koestler’s concept of ‘bisociation’. Briefly, bisociation is the contraction of different matrices of thinking or established structures (which can even exclude one another) that make up new meanings through a process that includes comparisons, abstractions, categorisations, analogies, metonyms and metaphors. Otašević’s work brings together object and action; one material, the other immaterial, one spatial, the other temporal. The two poles come together so that the action is objectified and the object activated. As Koestler put it: ‘I have coined the term “bisociation” in order to make a distinction between the routine skills of thinking on a single “plane”, as it were, and the creative act, which … always operates on more than one plane. The former can be called single-minded, the latter a double-minded, transitory state of unstable equilibrium where the balance of both emotion and thought is disturbed’.21

Fig.8

Dušan Otašević

Sea! Sea! 1966

Collection of the artist

© Dušan Otašević

Courtesy the artist

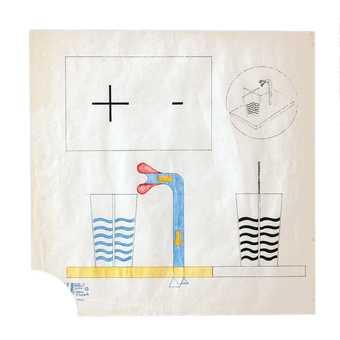

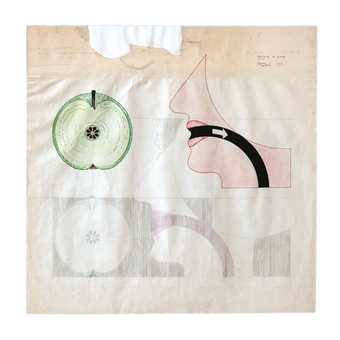

In To Drink 1967 (fig.9) and To Eat 1967 (fig.10), for example, Otašević represents these corporeal actions through the diagrammatic form. To Drink shows the body reduced to lips and the oesophagus with blue stylised water streaming through it, the action denoted by arrows directed down the throat. In To Eat, a fragmented female profile with the oesophagus highlighted in black faces a large halved apple with another arrow denoting its endpoint. As well as detailing the processes of eating and drinking, these two works also functioned as sketches for two sculptural objects. However, all of the flatness and instructional qualities remain in the three-dimensional works, as though they serve some functional, mechanical purpose (figs.11 and 12). Breathing (or smoking a cigarette, as a form of breathing), together with eating, drinking, shitting and pissing are the five basic functions of every human organism. In that they focus on this everyday corporeality, Otašević’s works from 1965 to 1967 are reductive in that the subjects are both abject and also represented in a sanitised way, corresponding to the disembodied world of visual mass-communication and popular culture. For example, the use of blue paint to represent urine, the contents of the toilet bowl and the glass of water removes the corporeal reality from its diagrammatic code, demonstrating bisociative humour. As cultural theorist Julia Kristeva has argued, excrement and other bodily emissions exist between subject and object, disturbing symbolization, and are therefore potentially disruptive to social reason.22 However, they are also common to all subjects in the social order. Otašević’s representation of the abject with socially acceptable signs reflects the use of these diagrammatic strategies in contemporary advertisements for personal hygiene products, including body wash, toothpaste and menstrual pads and tampons – particularly the latter in which blood is often represented by a more sanitary blue liquid.

Fig.9

Dušan Otašević

To Drink 1967

Kolekcija Marjanović

© Dušan Otašević

Courtesy the artist and Kolekcija Marjanović

Fig.10

Dušan Otašević

To Eat 1967

Kolekcija Marjanović

© Dušan Otašević

Courtesy the artist and Kolekcija Marjanović

Fig.11

Dušan Otašević

To Drink 1967

Collection of Slavica and Daniel Trajković

© Dušan Otašević

Courtesy the artist and Slavica and Daniel Trajković

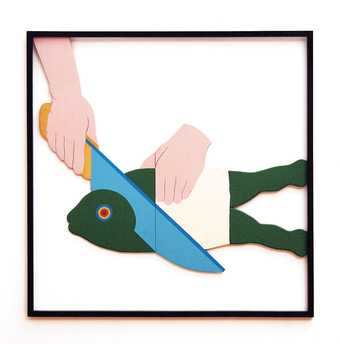

Fig.12

Dušan Otašević

To Eat 1967

Collection of Slavica and Daniel Trajković

© Dušan Otašević

Courtesy the artist and Slavica and Daniel Trajković

Other works by Otašević separate the bisociative linking of objects and action from the body. In To Cut 1967 (fig.13), for instance, a saw handle protrudes from a curved aluminium surface as if it has cut through it, but instead of a real slice one sees only a painted line. A similar procedure is applied in Still-Life with Fish 1967 (fig.14) in which a knife appears to cut off the head of a fish, but the fish and the knife are united into one object-action across a single board – a materialisation of the action generated by their encounter. In his Tools series from the mid-1970s Otašević explored the concept of object-pictures further, inscribing the representation of the object that performs the action (a tool) and the effects of the action performed by that object. In this series, hammers, saws, brushes, drills, files, pliers and other carpenter’s tools are foregrounded and transformed into the leading characters. The tools are not merely the means to produce work or passive consumer objects rendered in pop art style, but his co-workers.

Fig.13

Dušan Otašević

To Cut 1967

Collection of Slavica and Daniel Trajković

© Dušan Otašević

Courtesy the artist and Slavica and Daniel Trajković

Fig.14

Dušan Otašević

Still-Life with Fish 1967

Museum of Contemporary Art, Belgrade

© Dušan Otašević

Courtesy the artist and Museum of Contemporary Art, Belgrade

Pop art without commodity fetishism

Otašević summarised his working procedure in a statement from 1969, claiming: ‘I make an object in the way a carpenter makes a cupboard. In the way a tinsmith makes a drainpipe. There is no mystery about it. No muse.’23 For Otašević, to be a carpenter is neither an ironic performance nor a romantic mystification. It is more a state of life as action, a mobilisation of people, things, representation and space. To be a carpenter means to be surrounded by materials and tools, but it also means to participate in the creation of forms of sociability. Of course, the identification between artist and worker, or in general the relationship of an artist and ‘artisan’ has purchase. However, the moment when this relationship first acquired political, theoretical and practical urgency was the period after the October Revolution in Russia when constructivists and productivists worked to foster new social relations between labour and art, and material objects and social processes. Although Otašević was not introduced to the Russian avant-garde at the Belgrade Art Academy in the early 1960s, in the late 1980s he was involved in re-thinking, or retro-thinking, the local avant-garde legacy.24

At this time Otašević, together with writer Branko Vučićević, created a project about an imaginary avant-garde artist named Ilija Dimić, whose practice apparently included the making of objects and constructions, paintings and drawings, photographs and texts.25 While the circumstances of this project – and a consideration of other works from the 1980s in Yugoslavia which also fictionalised history and re-actualised or ‘reworked’ the historical avant-garde – are beyond the scope of this article, it sheds light on Otašević’s knowledge of and interest in a constructivist understanding of the material object.26 For some of the works by Ilija Dimić, Otašević used his own earlier, unexhibited works as well as new works made in a constructivist idiom. As such, the simulation of an avant-garde proposition attributed to Dimić was in fact an important facet of Otašević’s work.27 Although, as previously stated, Otašević’s knowledge of constructivism was very limited in the 1960s, Russian constructivist and productivist thought and action are nonetheless useful for thinking about Otašević’s understanding of the relationship between an object and an action, between labour and consumption. Of course, these relationships figure in the wider context of modernisation in the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, and the economic reforms which set out to link aspects of capitalist production and socialist ideology. As such, parallels can be drawn between the period of the New Economic Policy (NEP) in the Soviet Union in 1920s and the economic reforms in Yugoslavia in the 1960s. Both attempted to develop a form of small business that could ‘prefigure’ organised and industrialised production. Simply put, this was thought to create a foundation for the economy which could overcome the capitalist fetishising of goods over labour and link production and consumption, work and leisure, in a more humane way. These measures were about transforming the capitalist form of fetishism, not by means of an ideological asceticism but by fostering an interest in making as a form of socialisation and, as such, challenging the association of work and the creation of objects with the processes of alienation and reification demanded by capitalism.

The art historian Christina Kiaer has criticised interpretations of the Russian avant-garde which claim that its ‘dream’ was actualised in the practice of the Stalinist bureaucratic state, and has challenged art historian Peter Bürger’s separation of the avant-garde and popular culture. Kiaer has shown that the writings of the productivists (in the journal LEF) and the activities of artists such as Alexander Rodchenko and Vladimir Tatlin in the 1920s cannot be understood as outlining an authoritarian social model based on utopian totalitarianism.28 She has suggested instead that certain leading productivists should be read in the context of the NEP, where the legacies of capitalist practices were analysed and a confrontation posed between production (as exploitation of workers) and consumption (as bourgeois enjoyment), leading to a vision of a new society that would overcome alienation and commodity fetishism. The NEP ascertained that the functional system of consumption was the necessary counterpoint to the system of production and that the issue of consumer desires was a real problem for the new Bolshevik state. The object – as a mediator between production and consumption – became the arena for carrying out reforms that would maintain certain aspects of the capitalist market freed from commodity fetishism. Along these lines Boris Arvatov, one of the leading avant-garde theorists of Russian constructivism, known for his technicist and productivist, but most of all utopian, rhetoric stated: ‘It is obvious that forms of social consumption are not primary-that they are defined by production-but without directly studying them it is impossible to grasp culturally the style of a society as a whole’.29 In order to separate the commodities and consumer relations in capitalism from the need to reconsider the concept of consumption in the socialist order, he began from the thesis that commodity relations in capitalism create a social passivity not only because the worker is alienated from the production but because the very form of commodity makes the objects passive, non-creative and immobile. Instead Arvatov proposed an elusive notion: that a ‘Thing’, not confined to a private sphere in socialist culture or devoid of a connection with labour, would provide a social modality of existence that would surpass the mysticism of commodity fetishism and be closely linked to production and all other kinds of collective enterprise. To this end, he wrote: ‘The Thing as the fulfillment of the organism’s physical capacity for labor, as a force for social labor, as an instrument and as a co-worker’.30

Although inspired by the rhetoric of productivism, Arvatov understood that the subject is not formed only in the sphere of production but also outside of their work through ‘free time’, leisure, recreation and consumption. Because of this he insisted on overcoming the dualism that places the ‘everyday’ in opposition to work, and therefore the separation of the activity of consumption from the activity of production. For Arvatov the legacy of capitalist class structure produces this dualism through the ‘monism’ of the proletarian material culture.31 Commodity fetishism is the most difficult obstacle for this enterprise and Arvatov saw in the concept of the socialist ‘Thing’ an object that actively changes and enriches the consciousness in contrast to the capitalist commodity form, which encourages passivity because of its dependence on private possession.32 Instead of the ‘commodity fetish’ Arvatov proposed a form of ‘utilitarian fetish’, animated through a permanent connection with production and not made passive in an isolated sphere of consumption.

Without an adequate model of ‘socialist consumption’, which Arvatov linked to the concept of the ‘socialist Thing’, consumerism has remained a logical social consequence of capital’s rule over labour. This took hold in Yugoslavia in the 1960s when consumerism arrived with the economic reforms, replacing the communist utopia, which it symbolically denigrated with a more aggressive dreamworld.33 A cultural difference was established on the basis of political orientation, responding to the pro-reform part of society that created its social fantasy from a symbiosis of capitalist economy and the socialist state, and the so-called ‘hard-line’ communist part that fantasised about a collective ideological asceticism expressing dominantly anti-Western cultural sentiments. In Yugoslavia in the 1960s and 1970s consumerism was mostly confined to a provincial mentality that relied upon distinguishing between the world and the ‘small town’, while simultaneously transforming the world into something ‘domestic’.34 This encounter between the ‘small town world’ and the ‘wide world’ had more of an influence on Otašević than the seemingly elitist world of so-called high culture. The everydayness that Otašević was interested in was not a synonym for an idealised conceptualisation of ‘life’, but an arena for action – a materialisation of the basic performative structure of a simple sentence comprising a subject, object and predicate. Life is the place where work and consumption enter into a relationship, where trade and culture, new and old, capitalist habits and socialist ambitions are conveyed, conducted and re-worked through the body and its physiological limits.

This goes some way to explain Otašević’s interest in carpenters, wall painters, dyers, sign painters and other petit-artisans who work on the margins of normative art. Importantly he never mystified them as ‘naive artists’ in the way that high modernism institutionally appropriated non-academic art. Instead he identified with the simplicity and resourcefulness of their work, which he used as tools to provide solutions to visual problems.35 He also embraced kitsch as a productive site, where solemnity is made comic and where humour parodies the absurdity of life. In his most extensive statement, dating from 1969, Otašević described how these elements defined his artistic attitude:

If your heart does not beat faster when you pass by the window of a cap-maker’s shop full of cut-off, happily smiling heads; if, while rushing to the bank or the parking lot, you do not stop before a nicely combed handsome man, forever good-looking and young, watching you from the label of a barber’s shop, then … then there is no point in your travelling to Rome, wasting your time at the Louvre, walking through the Hermitage.

If you do not notice the window of a glass cutter’s shop or, even more, turn your head away from it and spit, then, then it is a certain sign that you will never understand Rembrandt. I know, you will try, having improved your taste by roaming through dank museums, to remove the monstrous body of kitsch crawling all over the place – from your parents’ bedroom to congress halls and apartments of movie stars. Your efforts will be in vain, for the hideous kitsch is – a twin brother of high art. A Siamese twin.

Do not try to destroy kitsch because you will be left without your favourite tie, the one you are proud of, because you will lose fond mementoes from photo albums, you will be left without the opera, novels, a painting you adore, because you will be left without ideas for which you sacrifice yourself, because you will be left without your most precious lover in her ear-rings and slippers. And what would you need your life for then?36

Otašević’s world of kitsch rejects the world of petrified neo-classical decorations or the false splendour of petit-bourgeois mise-en-scène. The objects and pictures Otašević mentions in this statement are simple elements of the everyday and not pseudo-nostalgic fantasy: windows of barbers’, cap-makers’ and glass-cutters’ shops or slippers, earrings and ties. The world of small artisans and simple craftsmen, where things are directly produced and bought, also involves a process of constructing and forming the self in relation to objects; objects which are not merely commodities but active participants in a certain ‘style’ of living and community building. This was about highlighting the dignity of life in different economic conditions; in this way the turn toward consumption was not a submission to normative class determinants of style, but a forging of one’s becoming through style. It is a process described by the theorist Ina Blom: ‘what appears in an intimate linking of style and a being is the idea that appearance is not an issue of fitting into the given categories or expectations, but an issue of idiosyncratic becoming’.37

The needs of consumers were important in building the world of the individual and community in a process that directly opposed normative capitalist consumption. This had an effect on the objects of consumption too; it depended on rough, not yet standardised objects that had a direct influence on the relationships they shaped. These artisanal objects entered the world to be consumed, imperfect, with traces of the production visible. Indeed these characteristics are integral to Otašević’s work and his artistic identity. The idea of an ‘amateurish’ working ethos was, for him, capable of replacing the modernist mystification and celebration of the artist. As he wrote: ‘I do not take a few steps backwards, blinking, to see what an object looks like, and I do not have to pose in front of my works in my underpants’.38 Otašević believed that it was possible to create a working ethos without an ideological idealisation of production (even without an idealisation of the worker); an ethos which did not reject the need to play or to show weaknesses in the working process. Rather he emphasised the need to link the working process to life, because ‘Things’ are not separate from life, and the work is linked to the one who works and lives with his work. The writer Bora Ćosić described the ‘great carpenter of painting’ saying that behind the doors of his workplace or his studio one could hear ‘the beating of a hammer, the quiet humming of the saw, the noise of the sand-paper, as if hundreds of diligent insects were at work inside’.39

Continuous with Arvatov’s understanding of the socialist ‘Thing’, it is crucial to insist on a relationship between object and working process, outside of the functionality of production (modernist Fordism), which reifies subjects and fetishises objects. Instead this relationship can be thought of as full of intermissions, delusions, corrections, re-workings and various do-nothing tactics of playing and relating to one’s own body and its weaknesses. And in those petty tactics of la perruque, to use sociologist Michel de Certeau’s phrase, there lies the notion that the simplest low-tech everyday ‘tactics of the use’ can shape an egalitarian concept of culture.40 Arvatov remarked that: ‘By taking a cigarette out of the cigarette-box, putting on the coat, or the cap on one’s head, by opening the doors, all these trivialities acquire their qualifications, their not so unimportant culture’.41 Similarly the Russian art theorist Nikolai Punin remarked in the 1920s: ‘We need things simple and primitive just as our everyday life is simple and primitive’.42 In his sketches of usable objects (working clothes or the house fire-stove) Tatlin tried to fight the ‘old-fashioned’ everyday practice of proletarians and peasants, imagining the possibility of improving such practices through the culture of the new involvement with objects. For Tatlin the necessity was to remove objects from the petit-bourgeois everyday, from the phantasmal comfort that distanced them from the direct experience of labour. The socialist Thing is therefore an active object in continual becoming. It is not the object of human thought, as it might be in an idealistic distinction between thought and matter. Rather it is constituted through a practice which opposes that difference. The simplest things and actions thus possess the potential to become active objects of culture distinguished from passive consumer products because they carry in them the potential to awaken us from the commodity-fetishist phantasmagoria. This is the source of Otašević’s socialist proposition: pop art without commodity fetishism.