As artists continue to discover the archive and explore ideas of the archival, often in collaboration with collecting institutions, there seemed to be a need for a reminder of earlier projects that sought to bring artists and archival collections together – initiatives that aimed to stimulate interactions as part of the creative process.

The idea that artists might reinvigorate and activate collections in new ways no longer seems a radical concept, but this understanding of the possibilities of collaborations between artists and archives was not always so prevalent. As is often the case, it took pioneering individuals to change sets of ideas about what artists do, what museums and archives do, and the role of the arts beyond, and behind, the gallery.

Angela Weight was Keeper of the Department of Art at the Imperial War Museum between 1981 and 2005, and throughout her time there she championed the idea of commissioning artists to work alongside the Museum’s collections and archives, encouraging them to reflect on the institution’s place in shaping the memory of modern warfare, a role it has performed since its founding in 1917.

During the First and Second World Wars, the British government commissioned artists to make records of each conflict both abroad and on the Home Front. The Imperial War Museum reinstated this tradition in 1971 by creating the Artistic Records Committee to commission artists to respond to modern conflicts in which British Forces were involved. The projects discussed here were initiated by Angela Weight through the Department of Art in the 1980s and 1990s to provide a critique of the institution itself.

Catherine Moriarty

I wanted to begin with this work by Gilbert & George. I remember it hanging in your office at the Museum and wondered what led you to purchase it?

Angela Weight

Gilbert & George had been making postcard sculptures since the late 1970s and I was very interested in their work. I remember meeting the late David Brown at a private view and him telling me that the Tate were keen to buy some postcard sculptures, and he said he was going to see Gilbert & George. This prompted me go along to the Anthony d’Offay Gallery where I spoke to Anne Seymour and asked if she could help me acquire something. Just two weeks later she phoned me up and said ‘they’re here’, and there were these two pieces which could not have been more right for the Imperial War Museum.

Catherine Moriarty

In many ways they are very representative of your view of the work of the Department of Art. Gilbert & George have always been collectors and in some ways these works are like mini archives. They are about arranging, about ordering, about creating meaning with the structuring of things, very much the kind of work that archivists and curators do. So, in some ways, we might see them as a step towards what was to be the first artists’ residency at the Imperial War Museum in 1984.

Angela Weight

Artists’ residencies were fairly ubiquitous by the early 1980s. They came out of the Artist Placement Group with John Latham, Barbara Stevini and others. A version of them, somewhat to John Latham’s displeasure, was taken up by the Arts Council. Quite a lot of residencies were funded all over the country by various kinds of organisations, but apart from the National Gallery that started its artists’ residency scheme – I think – in 1981, there had not really been any artists working within major public spaces, certainly not any of the national museums. My aim for the Department of Art at the Imperial War Museum was to make the Museum a venue for art because it had this fantastic art collection that was really very little known. One way of doing that was to bring artists in. If you are bringing in contemporary art you are bringing in a new public. It developed from a conversation with Lesley Green who was working at the Arts Council, and she agreed to find some matching funds if the Museum would find the rest for a residency. Our first resident was Denis Masi in 1984. It was just a three-month residency which, as he told me, was nowhere near long enough. As you did at that time, you had to find a studio space because a condition of the residency was that there had to be a kind of educational element: the artist had to be available at least one day a week for the public to come and talk to them – a bit like an animal in a zoo actually. But he spent a lot of time looking at the different archives in the Museum, of which there are seven. I should point out that besides the Department of Art there is Film, Photography, Sound, Documents, Printed Books and Exhibits & Firearms – and he particularly worked with Exhibits & Firearms, Sound, and I think to some extent Film and Photography.

Catherine Moriarty

You have described the Museum, at that point, as having a risk-averse culture. Could you say something about Denis Masi’s working processes and the way he interacted in the Museum with departments that may not have had that experience, or that contact, with artists previously?

Angela Weight

Denis is very good at interacting with people and he was genuinely interested in the Museum. He was also aware of how critically it was viewed by people on the Left, and even by the art world, as rather a fuddy-duddy, irrelevant organisation. In fact, he said that people sometimes, when they came to see him, said, ‘What are you doing here? You should not be in the Imperial War Museum. It is wrong for an artist to be involved with war.’ But he saw the Museum as both a monument and a shrine to the memory of people in the twentieth century.

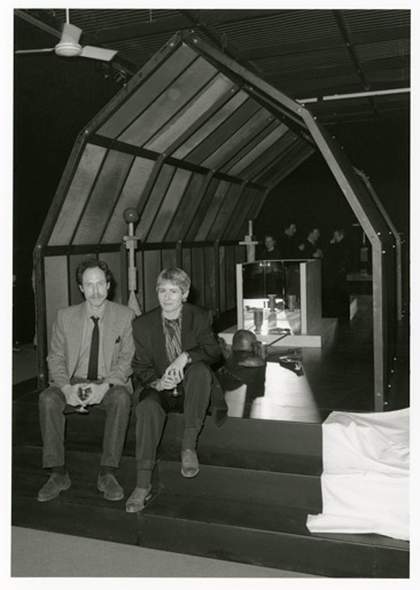

Fig.3

Denis Masi’s Shrine 1988, with the artist and Angela Weight in the foreground

© Denis Masi

Catherine Moriarty

Clearly, Denis saw his period at the Museum as part of a research process . Would you like to talk about the eventual outcome of his project?

Angela Weight

While he was a resident at the Museum I put on a show called Recent Acquisitions and in tandem with this we showed one of Denis’s works called Barrier, so the public could at least see the kind of work he made. But in the three months that he was at the Museum it would have been impossible for him actually to make anything. Shrine really came out of the residency later. He worked on it over the next three years and it came to fruition for a touring exhibition initiated by the Third Eye Centre in Glasgow. When the exhibition came to London, the main part was at the Serpentine, while Shrinewas shown at the Museum. It was a very large piece in one of the ground-floor galleries. It was made of metal and canvas, almost Nissen Hut-like in appearance, and inside were various objects that Denis had cast in bronze from actual artefacts in the Museum. For instance, there was a German drinking cup, a French bayonet and a Luger pistol. It was a very complex piece, rich in associations and meanings. In fact, I would go so far as to say that it is one of the most important works of his career. It also initiated a change in his practice because he started using what we might call ‘fine art’ materials for the first time.

Catherine Moriarty

That brings us to Bill Woodrow. He, too, had previously worked with found materials, and yet his contact with you and his time at the Museum led him to use monumental, enduring materials for the first time. After the project with Denis Masi, you arranged another residency with Stuart Brisley in the late 1980s, and that coincided with your work with Bill Woodrow and the exhibition Point of Entry in 1989.

Fig.4

Bill Woodrow

Refugee 1989

© Bill Woodrow

Fig.5

Bill Woodrow

For Queen & Country 1989

© Bill Woodrow

Angela Weight

The situation was completely different with Bill. Again, I very much liked his early work when he was cutting things out of found objects like washing machines. I asked him if he would make a show for the Imperial War Museum reflecting on the institution and its collections in some way. But it was not a residency in that he did not have to be in a studio space or meet the public. At that time a major redevelopment of the interior of the Museum was talking place and a huge atrium had been created in which there were lots of what the Museum considered to be iconic objects, like the First World War bus, various guns and missiles, and suchlike.

Catherine Moriarty

Tanks on pedestals?

Angela Weight

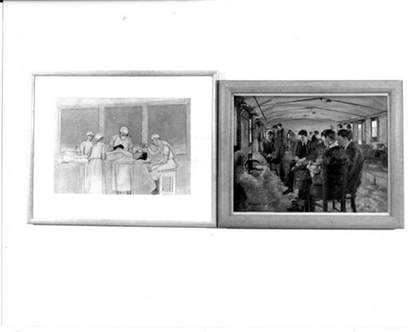

Yes, tanks all nicely painted, polished and without a speck of dirt anywhere. Bill would come to the Museum and just spend time in this atrium, watching how people reacted to things and overhearing conversations. He was responding to these objects that were designed to kill people. The effect of these weapons is not really reflected in the Museum very clearly. They have become objects of contemplation rather than weapons of destruction. And so he came up with some really very critical sculptures. We acquired Refugee for the collection. For the show he asked me if he might select works from the art collection and hang them in the gallery the way he wanted. It was great to have an artist burrowing about in the art collection and looking at it in a completely different way from the curators. He picked things that connected with what he was trying to do with his work. He wanted to hang these works very close together in a non-hierarchical way. For example, two First World War paintings by H.S. Williamson, Human Sacrifice – In an Operating Theatre, and J. Hodgson Lobley, The Toy-Makers’ Shop at the Queen’s Hospital for Facial Injuries; Sidcup (fig.5); a lithograph by Frank Brangwyn, Kitchener’s Appeal, and one of Sir Edwin Lutyens’s designs for The Cenotaph (fig.6).

Fig.6

View of the installation of Bill Woodrow’s exhibition Point of Entry

showing H.S. Wilkinson, Human Sacrifice – In An Operating Theatre, 1918

and J. Hodgson Lobley, The Toy-Maker’s Shop at the Queen’s Hospital for Facial Injuries, Sidcup 1918

© Imperial War Museum

Fig.7

Frank Brangwyn, Kitchener’s Appeal 1915

Sir Edwin Lutyens: Design for The Cenotaph 1920

© Imperial War Museum

Catherine Moriarty

Woodrow created sculpture that had that same physical presence as the tanks and the guns and combined this with selections from the archive to explain the processes and the trauma of conflict.

Angela Weight

Yes, exactly.

Catherine Moriarty

The next project I should like to talk about is the exhibition you undertook with Mark Fairnington in the late 1990s. Unlike Masi and Woodrow who were concerned primarily with the objects and spaces of the Museum, Mark was interested in the two-dimensional documentary material within the Museum. As I understand it, he approached you in the first instance?

Angela Weight

Mark had found a First World War first-aid manual. The kind of manual illustrated with line drawings of a simple, direct nature, though they might deal with something quite gory, such as how to deal with a broken leg, or how to deal with an explosion. It was actually the dealer, Anthony Stokes, who approached me and said Mark wanted to know if we had more of this material. We said that we had lots of that kind of thing in the Department of Printed Books. The Department of Art also has sets of cigarette cards bearing similar instructional images, and an extraordinary collection of the original black and white artwork for illustrations in the Illustrated London Newsin the Second World War. Mark spent almost two years looking around the collections; it took a while for him to establish what it was he really wanted to do.

Fig.8

Roland Davies,

V2 Rocket Falling on a London Street

Drawing for the Illustrated London News, 1945

© Illustrated London News Ltd / Mary Evans Picture Library

Fig.9

Mark Fairnington

Untitled 1998

© Mark Fairnington

Catherine Moriarty

So you introduced Mark to a wealth of commercial art and instructional publications and manuals. That is what he found so engaging, and which prompted his Untitled drawings.

Angela Weight

He often distorted the image by lengthening them or changing them in some way. It is not that they are surreal but they are absurd and like the original drawings. It is their detachment that is so bizarre.

Catherine Moriarty

Like Bill Woodrow, Mark also wanted to exhibit his work alongside other items in the collections.

Angela Weight

Yes, models of camouflage ships from the Department of Exhibits & Firearms, and a wooden horse used for training, or that kind of thing, that he found in the museum stores at Duxford Airfield.

Catherine Moriarty

What’s going on here is the idea that if you remove objects and items from their everyday arrangements within the museum and display them in another context you invite the museum visitor, and the curators, to see things afresh. It is that idea of reinvigoration, and presenting a new vision that is so powerful about all these projects.

While Mark was at the Museum he also invited another artist to show with him?

Angela Weight

Yes, at that time Mark Fairnington was working with Mark Dean, a film and video maker, at the Ruskin School of Art. Mark Dean went to the film archive at the Museum and said to them ‘What have you got?’ The film curator said, ‘Well, what do you want?’ It would take more than twenty years to view the film archive from end to end! And this is a problem curators often find, perhaps less so now that things are on the web. People come along and say ‘What have you got?’, and you have to narrow the field. At that time – only ten years ago – you still had to look through card indexes. Mark found some German Second World War camera gun footage of the destruction of an Allied bomber. Camera guns have been fitted to fighter aircraft since the First World War. The camera begins filming automatically when the guns are triggered, recording the line of fire and any hits to the target. His film Untitled (Fw190A7 – Boeing) consists of this footage slowed down 5,000%, a cross with markers and five decades of dust.

Catherine Moriarty

Mark took the film and slowed it down so the actual process of death was elongated, and the film was displayed alongside Mark Fairnington’s installation.

Angela Weight

This was entitled Heavier than Air.

Catherine Moriarty

The projects that we have described so far are about artists’ interventions and artists’ curiosity about the contents of the museum. The next project and the one that follows are interesting because they’re about the museum as a power structure where the artist can intervene and present work, and in some way borrow the museum as a mechanism fordelivering. This is the box of negatives that started your collaboration with William Furlong.

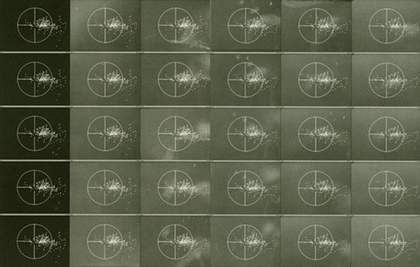

Fig.10

Mark Dean

Still from Untitled (FW190A7-Boeing) 1998

© Mark Dean

Fig.11

William Furlong

An Imagery of Absence 1999

© William Furlong

Angela Weight

Bill found this box in a market near Münster, in Germany, and inside it were glass plate negatives dating from about 1932 taken by an amateur photographer who was a scout master – this is the Wandervogel, a German scout organisation – and Bill printed them up. They are not high-quality photographs: the photographer’s finger sometimes appears on the print, some are a bit out of focus. But they are extremely telling because when you look at them you think that in a year or two there is going to be this cataclysm and what happened to these people? Are some of these people still alive? Bill is a sound artist and as a way of bringing the past into the present, and as a way of bringing this archive alive, he reactivated it, creating sounds which were broadcast in the gallery through speakers. As you walked round, you heard these ambient sounds and each photograph was titled with the name of one particular sound – the sound of the railway, the sound of birds. There were no voices – that was the whole point.

Catherine Moriarty

The sounds were described in German but obviously the experience of the sound and the way that sound was used to connect the present with the past and the past with the present is something that was beyond language. Additionally, it raises the point about archives respecting the whole. As I understand it, the prints were reproduced in their entirety, the good ones and the bad ones, and no distinction was made between them.

Angela Weight

The box that the negatives came in originated in Leipzig and had a Jewish name inscribed on it, making the work even more ironic.

Catherine Moriarty

‘Ironic re-inscription’ is the term that Marita Sturken used in her studies on post-memory. In Bill’s work, the use of sound powerfully activates that process.1

The final piece that we are considering brings us right up to date because it is actually on show at the Museum at the moment. Angela’s work in the Department of Art pioneered the way that we now think about the way artists might work. Would you like to talk about Steve McQueen’s Queen and Country?

Fig.12

William Furlong

Der Klang der Schritte in der Stadt, An Imagery of Absence 1999

© William Furlong

Angela Weight

As well as having a budget for acquiring work, the Department of Art also plays a pivotal role in what was called the Artistic Records Committee. This was set up in 1971, originally in response to the troubles in Northern Ireland. It is now called the Art Commissions Committee – we got rid of those two dreary words – ‘artistic’ and ‘records’. The Committee commissions usually one or maybe more artists a year to go to or make a response to whatever the current conflict is. Steve McQueen was commissioned to go to Iraq but in the time between the award of his commission and all the organisational work that it takes to get anyone out to a war zone, the situation became extremely difficult. In the end we managed to get the Ministry of Defence to take him to Basra but they would only take him for a week which did not really give him long enough. We tried to get him out to Baghdad a while later but it was totally unsafe, and so we were in a difficult situation. Eventually, Steve came back to the Committee with the idea to work with the relatives of soldiers, sailors and airmen who had been killed, to make commemorative stamps. The Museum spent a lot of time trying to persuade the Royal Mail that this would be a good idea, but the Royal Mail is a very conservative institution. Eventually, the work was made in conjunction with the Manchester Festival and it is still being added to, I am sorry to say.

Catherine Moriarty

An interesting point about this project is that the archive has been sourced from images that belonged to the bereaved. Rather than the archive originating from within the Museum, or being a government initiative, it is made entirely with material belonging to the families. It has been transferred from different domestic spaces, and repositioned by Steve McQueen in an archival system, with all its connotations of equivalence, order and objectification.2

Angela Weight

Yes, it is a traditional museum system. The case is a big oak box from which you can pull out these leaves and look at each individual sheet of stamps. The irony is that for many years in the Department of Art we actually housed a stamp collection. It belonged to the Department of Printed Books, but was housed in the art store in a very similar system with pull-out drawers – a hugely valuable collection which nobody ever looked at.

Catherine Moriarty

The Art Fund has bought Queen and Country and has presented it to the Museum, and so we have come full circle – an archive has been created as a memorial and by placing it in the Museum the artist sets off tensions between family/home/duty/country. If the facsimiles are eventually produced as stamps – and the Art Fund is campaigning for this – they will go back out into the world, multiplied many times over, and circulate in everyday and domestic space once again. The commemorative function moves on, beyond the museum.3

Drawing to a close, I should like to say how interesting it has been to go back to the Museum with Angela to research these projects. Initiated by the Department of Art, they were marginal to the Museum’s main work, and so the records are rather scanty. But it has been a fruitful process of discovery.

Angela Weight

It has also been interesting to talk to the artists again, and many of them have positive memories of their work with the Museum and that is important because the idea from the start was to create a dialogue.