Archives, it seems, are everywhere, both in popular culture and academic discourse. The BBC’s Radio 4 has taken to using the word ‘archive’ as a noun, without a definite or indefinite article, as in, ‘the programme will feature archive to tell the story of …’. Even the computer game character Sonic the Hedgehog has four volumes of ‘archives’ available for purchase, inviting fans to ‘travel back in time to where it all began’. At the other end of the scale, the change in name of the UK’s Public Record Office to the National Archive suggests that the archives are not so much an instrument of state as a collective memory bank. How should we interpret this current interest in archives?

The archive is popularly conceived as a space where things are hidden in a state of stasis, imbued with secrecy, mystery and power. Archives are seen as rows and rows of boxes on shelves, impenetrable without the codex which unlocks their arrangement and locations. For some the archivist is a rule maker, casting spells around archives (damsels in distress), which are suspended in time, waiting to be rescued and re-animated by users (in shining armour). Much has been written by historians about the experience of using archives and the impulse to rescue and rehabilitate not just the lives and actions documented in the archive but the very material itself – the stuff of history1 – while several recent novels feature archivists prominently (the summary of one describes an archivist as ‘proud gatekeeper to countless objects of desire’).

However, our feelings towards archives are ambiguous. In Ilya Kabakov’s The Man Who Never Threw Anything Away 1996, the main character has a room filled with a lifetime’s garbage, bearing witness to ultimately pointless efforts to classify and record all the links between the items:

A simple feeling speaks about the value, the importance of everything … this is the memory associated with all the events connected to each of these papers. To deprive ourselves of these paper symbols and testimonies is to deprive ourselves somewhat of our memories. In our memory everything becomes equally valuable and significant. All points of our recollections are tied to one another. They form chains and connections in our memory which ultimately comprise the story of life.2

At the same time, the protagonist feels bogged down by the accumulated waste and the debilitating burden of this garbage:

Why does the dump and its image summon my imagination over and over again, why do I always return to it? Because I feel that man, living in our region, is simply suffocating in his own life among the garbage since there is nowhere to take it, nowhere to sweep it out – we have lost the border between garbage and non-garbage space.3

There are perhaps connections to be made between this fascination with archives and a widespread sense that within Western capitalist societies we are surrounded by stuff but uncertain about what is significant. Even with the advent of the internet, we seek to order and privilege certain cultural objects over others (and individuals over others). Today our lives are documented in ways unimaginable to previous generations – as seen in recent debates about information security, both that held by government and that which we offer up ourselves on such sites as Facebook, tagging our pages and creating our own taxonomies. According to the French historian Pierre Nora, ‘our whole society lives for archival production’.4 At a time when we both crave and feel overwhelmed by information, the archive can seem like a more authoritative, or somehow more authentic, body of information or of objects bearing value and meaning.

The arrival of the personal computer has helped change the status of the archive in our daily lives. With the development of the idea of ‘archiving’ electronic documents, ‘archive’ has become a verb. A modern dictionary says that the verb means:

- to store historical records or documents in an archive

- in computing, to store electronic information that you no longer need to use regularly.

In addition, ‘archive’ as a noun is now used much more loosely than before, and has both a professional and a popular meaning. The conventional professional definition of the archive is:

- a collection of historical records relating to a place, organisation or family

- a place where historical records are kept.

However, the popular meaning of ‘archive’ seems to embrace any group of objects – often digital – which are gathered together and actively preserved. The word can also be used to suggest somewhat imprecise notions of historicity, age or retention. The popular understanding of ‘archive’, thus, has moved beyond the areas on which much theoretical discourse about the archive concentrates, and this change needs to be reflected in our professional realms. Archives no longer belong to the lawmakers and the powerful; archivists see themselves as serving society rather than the state. The archive theorist Eric Ketalaar has described this view of the archive as, ‘By the People, of the People, for the People’.5

While much discourse concentrates on the physical or notional locus of the archive, the other element of the professional definition (a collection of historical records relating to a place, organisation or family) is also worthy of attention, though the least known or understood outside the archive profession. It is easy to see what it is about museums that has both attracted and repelled artists. Susan Hiller, for example, has spoken of her interest in the ‘orchestrated relationships, invented or discovered fluid taxonomies’ of a museum.6 Christian Boltanski has said of the problems posed by preserving items within a museum setting:

Preventing forgetfulness, stopping the disappearance of things and beings seemed to me a noble goal, but I quickly realised that this ambition was bound to fail, for as soon as we try to preserve something, we fix it. We can preserve things only by stopping life’s course. If I put my glasses in a vitrine, they will never break, but will they still be considered glasses? … Once glasses are part of a museum’s collection, they forget their function, they are then only an image of glasses. In a vitrine, my glasses will have lost their reason for being, but they will also have lost their identity.7

As the debate about the museum and institutional critique developed, and the artist-as-curator became the artist-as-archivist, the archive became implicated by association in art discourse, though it has its own distinct principles and practices.

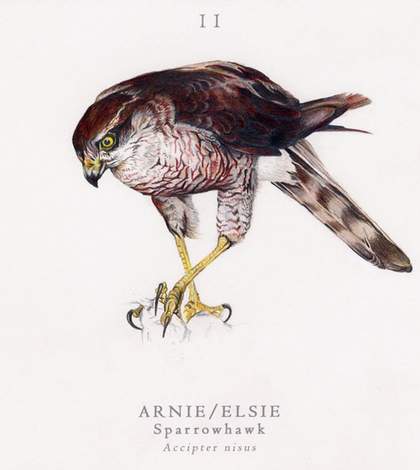

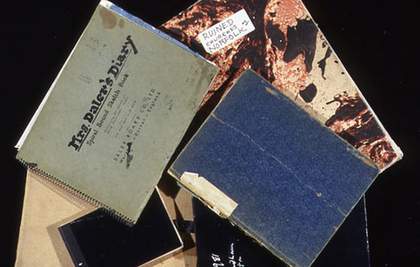

Fig.1

John Piper

Notebooks and sketchbooks from the John Piper Archive

Tate Archive TGA 200410

The main difference is expressed in the first definition of the archive cited above. The papers of the British artist John Piper, for example, comprise a body of material generated by one person’s life and which therefore belongs together. The shape and contents of that body of material are part of its evidential value. This may or may not include a particular original order in which it was arranged, reflecting the processes that created it. Alternatively, its significance may lie in the interrelationships between the component parts of the archive, which can also imbue each with authenticity. Archives are not placed within a pre-existing taxonomy or classification scheme in the way that libraries are.

Often, things are called archives that are really just groups of material. There is a major difference between the archive of John Piper, as described above, and a single document (let us say a sketchbook), taken from the original context of its production and placed with other, single documents, into what is known as a Special Collection, a collection of individual, decontextualised ‘treasures’. Such a collection is not generated by any activity other than collecting. By contrast, an archive is a set of traces of actions, the records left by a life – drawing, writing, interacting with society on personal and formal levels. In an archive, the sketchbook would ideally be part of a larger body of papers including correspondence, diaries, photographs – all of which can shed light on each other (for example, a diary can locate the artist in a particular place at a particular time, which can help date the contents of the sketchbook).

Hal Foster describes the nature of archives as at once ‘found yet constructed, factual yet fictive, public yet private’.8 There is a distinction to be made between the kind of archives which are often discussed – institutional records, generated by the actions and processes of the implementation of power – and private, personal archives. Tate Archive can be described as a formal collection of predominantly informal archives. Selection is necessary and inevitable, because as Ilya Kabakov suggests, we cannot keep everything, but the structure of individual archives is not essentially an institutional act.

Although no activity is objective or free of bias, a core principle of archival practice is to seek to be as objective as possible in what might be called the ‘performance’ archivists enact on the archive. This includes describing material neutrally, documenting what they do to the archive, and intervening as little as possible if an original order is discernible in the papers. Archivists aspire to a democratic facilitation, which seeks to give each researcher the same or similar experience of encounter. Archivists are aware that this process cannot be objective – for example, within the Institution Tate Archive’s holdings are viewed first and foremost as art records, while non-art historians would see them as documents of a much wider-ranging significance. Multiple readings of archive material are possible, through each user (student, art historian, theorist, artist) having the same experience of encounter without disturbing the traces for others.

This can be compared to what is known in archive theory as the ‘archive continuum’. Earlier phases of archive theory spoke of a life cycle: records were created, carried out their active purpose in supporting and documenting ongoing activities, and once no longer current, were either destroyed or retained for an archival purpose. In the case of official records, this purpose was often the supporting of a position of power and authority, which was embodied in the retention (in the sense of both the holding and the keeping) of the physical records. In the paradigm of the archive continuum, by contrast, the records do not simply go through a life cycle from creation and currency through to inactivity and the archive, but move in and out of currency, having qualities both current and historical from the moment of their creation. On its website the Archive School at Curtin University in Australia describes archives as ‘frozen in time, fixed in a documentary form and linked to their context of creation. They are thus time and space bound, perpetually connected to events in the past.’ It continues: ‘Yet they are also disembedded, carried forward into new circumstances where they are re-presented and used.’9 This relates to Hal Foster’s description of the archive as a place of creation, part of the embodiment of

its utopian ambition – its desire to turn belatedness into becomingness, to recoup failed visions in art, literature, philosophy, and everyday life into possible scenarios of alternative kinds of social relations, to transform the no-place of the archive into the no-place of utopia … [a] move to turn ‘excavation sites’ into ‘construction sites’.10

Or, as Kabakov says:

A dump not only devours everything, preserving it forever, but one might say it also continually generates something; this is where some kinds of shoots come for new projects, ideas, a certain enthusiasm arises, hopes for the rebirth of something.11

It is interesting to compare these evocations of a fertile archive, with Jacques Derrida’s ideas about difference, context and iterability. As Jae Emerling explains, ‘writing is associated with distance, delay and ambiguity … writing [for Derrida] must be iterable – repeatable but with difference … not even context can ensure the reception of intent in language. No context can enclose iterability.’12 There is no one fixed meaning of any archival document: we may know the action that created the trace, but its present and future meanings can never be fixed.

Other fundamental principles underpinning archive theory and practice – authenticity and the context of the record – are also eminently compatible with postmodernist thought in demanding that we do not take a document at face value but rather look at the process of creation rather than the product itself. An international body of professional archive discourse dates back to the nineteenth century. The father of British Archives is commonly agreed to be Sir Hilary Jenkinson, former Keeper of the Public Records, who, in his seminal Manual of Archive Administration of 1922, stated that archives ‘state no opinion, voice no conjecture: they are simply written memorials, authenticated by the fact of their official preservation, of events which actually occurred and of which they themselves formed a part’. Of course, archive theory has developed since then, in parallel with wider historical and cultural debates, and the authority of the document is now viewed differently. The Canadian archive theorist Terry Cook charts an evolution of archival theory from the tenets of Jenkinson’s era, which he describes as pre-modern positivism, to the postmodern approach informing the work of archivists today which ‘questions the objectivity and “naturalness” of the document itself’.13 As Jacques Le Goff has observed, ‘the document is not objective, innocent raw material but expresses past [or present] society’s power over memory and over the future: the document is what remains’.14

While Derrida and Foster take quite different approaches to the archive (the former concentrating on the broadly political significances of archives, the latter on a more personal, less structured, approach in which the archive is a mode of practice or a point of reference for the artist), both refer to the appeal, even the compulsion, of the archive, most strongly evoked in Derrida’s notion of ‘archive fever’ or ‘mal d’archive’:

We are all ‘en mal d’archive’: in need of archives … [we] burn with a passion never to cease searching for the archive right where it slips away … [we] have a compulsive, repetitive and nostalgic desire for the archive, an irrepressible desire to return to the origin, a homesickness, a nostalgia for the return of the most archaic place of absolute beginning.15

Importantly, Derrida writes not only about the archive as a site of power and authority but also about the ambiguous and fragmentary nature of its contents – the ‘presentness’ and absence of traces that make up archives, the fact that they record only what is written and processed, not what is said and thought. This incompleteness and instability of archives, however, can be overlooked if we focus too much on the archive’s exercise of power and not enough on the principles which underpin its approach to any construct, document or text.

Derrida’s ‘mal d’archive’ can be found in many different people and walks of life. Why do we – archivists, artists, art historians, family history researchers, fans of Sonic the Hedgehog – long for archives? Perhaps because we find ourselves there and we can project onto the archive our imaginings. As with memory, we can be as selective as we like in what we take out of the archive, even while it claims to present the whole story. Those endless shelves of boxes seem to offer an illusion of authority and apparent truth; yet we all know there is no such thing. It also evokes what Derrida has described as a Western impulse to look for beginnings and the belief that these can be found in the archive. For her part, Carolyn Steedman has written about this aspect of ‘archive fever’:

The past is searched for something … that confirms the searcher in his or her sense of self, confirms them as they want to be, and feel in some measure that we already are … [but] the object has been altered by the very search for it … what has actually been lost can never be found. This is not to say that nothing is found, but that thing is always something else, a creation of the search itself and the time the search took.16

Archivists find that researchers not only come with ideas of what they hope to find but also cannot accept that it is not there. There is an expectation of completeness. But, in reality just as much as in theory, the archive by its very nature is characterised by gaps. Some of these are random – the result of spilt cups of tea, or the need for a scrap of paper for a shopping list. Any archive is a product of the social processes and systems of its time, and reflects the position and exclusions of different groups or individuals within those systems.

It is this latent ambiguity which attracts us all to archives: the layers of meaning, tales and enactments beyond the immediate informational content. In his article Foster gives examples of the use of archives in contemporary art practice. I simply offer briefly a few other examples illustrating some of the points I have made.

Deller & Kane’s Folk Archive is an example of where the artist adopts the role of an archivist or collector. Similarly, the Enthusiasts: archive project of Neil Cummings and Marysia Lewandowska collects and presents amateur film from Polish film clubs. Both archives comment on collecting and, particularly in the latter case, raise questions about the privileging of certain kinds of documents over others. Essentially, both these are collections rather than archives, but the use of the term ‘archive’ is an assertion of the changed status of this material, which has gone from obscurity to preservation and presentation. Cummings and Lewandowska make the following distinction between an archive and a collection:

Archives, like collections in Museums and Galleries are built with the property of multiple authors and previous owners. But unlike the collection, there is no imperative within the logic of the archive, to display or interpret its holdings. An archive designates a territory – and not a particular narrative. The material connections contained are not already authored as someone’s – for example, a curator’s – interpretation, exhibition or property; it’s a discursive terrain. Interpretations are invited and not already determined.17

This view informs their aim to ‘stimulate interest and discussion into the nature of creative exchange, the function of public archives and the future of the public domain’18

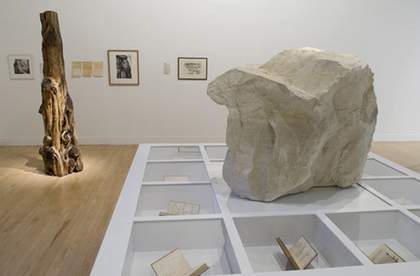

Fig.2

Goshka Macuga

Objects in Relation 2007, as shown in Tate Britain 2007

Photgraph courtesy Sam Drake, Tate Photography © Tate 2007

By contrast, Goshka Macuga has used the archive as a site of personal research, echoing Steedman’s description of the search for the self in the archive which in turn becomes something quite different. Macuga uses archival material as a territory for seeking, or creating, an authority through which she can explore herself:

It’s not the attempt to project my identity as much as to find my identity in the process [of creating an artwork]. I’m not living in my own country. I’m not speaking my mother’s language. The history that I’ve been educated with in Poland is not valid any more, because all the history books have been rewritten, so in a way I’m just creating my own histories, based on objects and artworks and certain experiences.19

Macuga’s 2007 exhibition in the Art Now series at Tate Britain used material drawn from the archives of Paul Nash, Eileen Agar and the Unit One group, and the borders between the personal and private aspects of the lives of these individuals, to express something of herself.

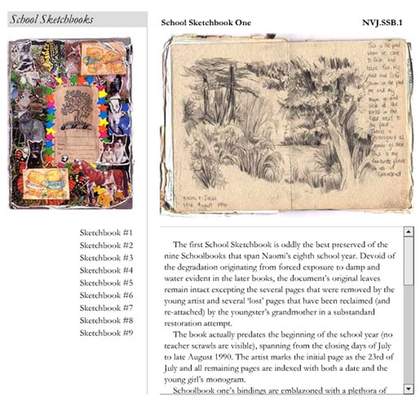

Fig.3

Page from Jamie Shovlin’s online resource Naomi V. Jelish

Jamie Shovlin’s fictitious archive of Naomi V. Jelish shows an extraordinary attention to detail in creating a false archive of a fictitious teenage girl and a life story for her which the project seeks to interpret in order to gain insights into her work. The project presents the archive on a website, which apes the forms of the institution of the archive by providing catalogue numbers and descriptive texts. The creative mileage which Shovlin found in this idea reflects the enormous potential of the archive and its methods as a ‘site of construction’.

Digital archives are often seen as a democratised solution to the issues raised by the role of the host institution and its selection processes, and by the paradox of wanting to keep everything yet the impracticality of doing so. What will the sheer volume of material mean for researchers in the future, especially if it is decontextualised and without external authentication (as is the case of the fictitious archive of Naomi V. Jelish)? Keeping everything is not a solution: as Ben Highmore wrote recently of the Mass-Observation archive, ‘by inviting everyone to become the author of their own life, by letting everyone speak about everything, the vast archive of documents became literally unmanageable’.20 The internet suggests permanence by using terms such as ‘autoarchiving’, but this is an illusion. The material needs to be actively captured and preserved. Archives that survive must inevitably be kept in some kind of houses of memory, whether real or virtual. The act of remembering involves both storing and retrieving: it is not a passive process, especially in the digital age. To be able to confirm the original context and provenance of archives will become more important than ever.

In the increasingly overlapping environments of creation, curation and consumption of archives, I should like to see new, fertile readings of the relationship between archivist, artist and researcher. Where boundaries are less defined, information and practices must and should be exchanged. Just as archivists engage with the meaning and implications of their activities, as well as the needs and interests of their researchers, so the theoretical discussion of the archive should properly understand its practices and historiography.

Archives are traces to which we respond; they are a reflection of ourselves, and our response to them says more about us than the archive itself. Any use of archives is a unique and unrepeatable journey. The archive is attractive territory for the exploration of critical theory because of the processes it both documents and enacts, its contradictions and discontinuities. It is also appealing because of the way it both seems to reflect ourselves and yet so clearly does not. Let us not, amid these compulsions, lose sight of what the archive actually is. Carolyn Steedman writes that the reality of archives is ‘something far less portentous, difficult and meaningful than Derrida’s archive would seem to promise’.21 I would say they are meaningful in myriad other ways.