Absence gives texture to the object and provides a frame for the thinking of distance. Absence does literally not accept the past. The distant is then what brings us closer and the absent – rather than absence – is a figure of return, as one says of the repressed.1

Pierre Fedida

The aim of this paper is to discuss the relation between trauma and representation in the work of Chilean artist Alfredo Jaar (born 1956), mainly his installations dedicated to Africa, in particular the Sudan and Rwanda. I shall take a closer look at how the artist engages with atrocities, whether of famine or genocide. I shall also examine how his installations both provoke and disarm our voyeuristic gaze, which so often underlies our engagement with the spectacle of atrocities. I shall argue that the artist toys with the mechanisms of trauma, reprogramming the shock dynamics of trauma and substituting the aesthetics of the wound with the ‘document’, which I understand as ‘the contextualisation and integration of image and event beyond and against the politics of global information’. In the ‘document’, the post-traumatic gaze is both revived and buried, acknowledged and mourned. The space of denial, which is a matter of shock or politics, is obliterated in the time and space of the ‘document’ where the viewer can finally encounter, engage with and be present in the missed encounter of the traumatic event.

The 2007 Alfredo Jaar retrospective at the Musée Cantonal des Beaux-Arts in Lausanne, Switzerland, shown later that year at the South London Gallery, displays some of his earlier, as well as more recent, inquiries into the politics of the image. Alfredo Jaar has extensively investigated the power relations which affect, govern and structure images, in particular, their perception and reception by the viewer/witness/consumer in the age of globalisation. The art of Alfredo Jaar exposes and frames the mechanics of power of the image. His art productions perform a critique of the act of seeing by revealing and exposing the underlying operations of montage and editing which sustain our perception of the world and its global events, that is the reality presented by the media and the world of so-called ‘information’. ‘Information’ is as much about disinformation as it is about information because images are selected, edited, presented and promoted while others are ignored or denied on a basis which ultimately obeys a political agenda. Jaar exposes the disjunction between reality and information in an act of resistance to the master narrative of global information, an artistic engagement that one could understand, following Georges Didi-Huberman, as an ‘art of counter-information’.2

This gesture of contestation appears in Jaar’s Untitled (Newsweek) 1994 which displays all the Newsweek covers that appeared during the unfolding of the Rwandan genocide. Every cover is accompanied by the historical facts pertaining to the genocide and its monstrous body count which every week added up another hundred thousand additional unreported and anonymous victims. The reality of genocide is absent from the Newsweek covers which focus instead on, in comparison trivial Americana, such as the deaths of Kurt Cobain, Jackie Kennedy, the trial of O.J. Simpson and the high-tech ‘gender gap’. It is only in August 1994 that the first Newsweek cover dedicated to the Rwandan genocide appears.

Jaar challenges us as viewers/consumers by confronting us and even, in the case of The Sound of Silence 2006 (fig.1), by trapping us into the political fabric of the image. Images are not facts, nor documents as the events of Timisoara demonstrated when real bodies were used as evidence of a fake massacre (images which prompted the Romanian revolution against Ceaucescu’s regime), or the Daily Mirror’s fake images of abuses of Iraqi prisoners by British troops in Basra, abuses which did happen but, unlike those of Abu Ghraib, were not photographed. In order to counter the gimmicky effects and affects of the visual image, Jaar often translates the image into words in order to conjure an objective narrative and ‘document’, operation that Georges Didi-Huberman qualifies as ‘documentary poetics’.3 Only the ‘document’, where an image and reality are coupled and integrated, can do justice to the complexity, genesis and destiny of the event which by far exceeds the frame of the image.

In Field, Road, Cloud 1997, three photographs can be viewed which, as the title suggests, are pictures of a field, road and cloud in Rwanda. The poetic nature of the images is challenged when the image is translated into a ‘document’ and the translation is juxtaposed with its photograph. We then learn that the three images are sites related to atrocities where people were brutally murdered. Jaar also uses documentary photographs to undermine certain unchallenged data. In Rushes 1986, the gold rate is juxtaposed with a photograph of a Brazilian gold digger or garimpeiro, a virtual slave whose work benefits the Brazilian government before being exchanged on the global market, a shocking reality Jaar had himself witnessed and documented in the Serra Pelada. The ‘document’ in Jaar’s work becomes a critical tool against the politics of global information as much as against globalisation itself.

In order to set up the ‘document’, Alfredo Jaar contextualises the image/data by recreating a unique environment and public space which enables the visitor to experience and understand the political fabric of global information, that is, the tension, and in some cases opposition, between image and information, fact and reality. This operation is not dialectical in the sense that the tension and opposition between information and reality is maintained and never resolved. The art of counter-information of Alfredo Jaar establishes this opposition in order to undermine, attack and bring down the so-called reality of information. The ‘document’, as weapon of counter-information, is much more than a mere text because it articulates, as Griselda Pollock remarked, an ‘encounter for viewers’.4 This encounter collapses traditional separations between object and subject. The viewer is not external to the work of art or to the fabric of history but integrated within the frame of the image, often through the use of mirrors where the viewer becomes a participant within the historical frame of the event staged by the artist. Alfredo Jaar thus expands the double surface of the ‘document’ by expanding time as well as space in order to set up a spatio-temporal armature specific to the historical event captured in the frame of the image. In the ‘document’, the event becomes an architectural space which can be experienced and visited by the viewer.

Fig.1

Alfredo Jaar

The Sound of Silence 2006

© Alfredo Jaar courtesy Galerie Lelong, New York

One such work of art is The Sound of Silence 2006, the most recent and most powerful work displayed in Lausanne’s Palais de Rumine. The Sound of Silence contextualises the infamous Pulitzer-Prize winning Kevin Carter photograph first published in the New York Times in 1993 which shows us a child starving on its way to a feeding centre in the Sudan under the hungry gaze of a vulture. Instead of telling the story of the little Sudanese girl whose fate is unknown, Jaar focuses on the man behind the famous image, on what happens behind the frame. The historical event of famine in the Sudan captured by the photojournalist is no longer an iconic image of famine belonging to the world of ‘information’ but a complex and radical encounter where Kevin Carter, who, as reporter, embodies the pole of ‘information’, is the one most affected by the encounter, although his presence is not embedded in the image. While the little girl supposedly finally made it to the feeding centre (without the help of Carter) and might still be alive, the journalist is dead. The image which marks the encounter between Carter and the little Sudanese girl is a moment of reversal and exchange.

The Sound of Silence sets up the space of the image in a large cube. One of the external sides of the cubic structure is illuminated by a series of blinding white neon lights, violently contrasting with the dark interior of the cube. It takes eight minutes in this small camera obscura to understand and experience the multiple and interwoven tragedies of the Kevin Carter photograph. The story of Kevin Carter unfolds in writing and silence on the screen. The biographical narrative of the South African freelance photographer is a narrative of failure, soul-searching and trauma which enables the viewer to identify and empathise with Carter, who sadly committed suicide in 1994, aged 33. Kevin Carter’s narrative culminates in the traumatic encounter with the starving little girl in the Sudanese bush. The cruel subtext lies in the fact that Carter waited twenty minutes, watching the little girl crawl in desperation in the hope that the vulture would spread its wings – which it does not – in order to get a better photograph. The text is only interrupted once by four violent and blinding flashes turned against the viewer. The violent breach of the scopic field reverses the position of the viewer/voyeur, now violated by the flash and victimised like the Sudanese child. Carter’s picture then appears furtively on the screen and the narrative ends with the destiny of the image and suicide of the photographer. The image has only appeared for a fraction of a second – the actual time it took for the image to be recorded – but the frame of its cruel history and destiny will haunt the viewer throughout the rest of the visit.

The Sound of Silence manages to stage what Stanley Cohen named the ‘atrocity triangle’, which he understands in the following way: ‘in the one corner, victims, to whom things are done; in the second, perpetrators, who do these things; in the third, observers, those who see and know what is happening’.5 As Stanley Cohen further remarks, these roles are not fixed, on the contrary they are often exchanged and rotate among the participants of the ‘atrocity triangle’. The Sound of Silence collapses the separations between the three figures of the atrocity triangle. The photographer as witness is a perpetrator (a predator like the vulture who is waiting for the right moment to strike) but he is of course also a victim of his own photograph (he never forgave himself for not assisting the little girl). The ghost of the little Sudanese victim has haunted the memory of Kevin Carter until his death, thus turning into a kind of ‘mnemonic monster’. The scopic cruelty which sustains our own voyeuristic gaze, as witnesses, is violently inverted and thrown back at us and we find ourselves all of sudden on the receiving end of the peep hole, abject and stained by our own voyeuristic gaze mirrored by the screen. The Sound of Silence, as trap for the post-traumatic gaze, stages and disables the very mechanisms of scopophilia at work within the ‘atrocity triangle’. The image in Jaar is thus a site of trauma, with its violent breach of the subject’s protective shield and phenomenal increase of stimuli, which disrupts the psychic order and ‘fractures the fragile webs that provide the framework for our interface with the social, political, cultural and emotional realms in which we function’.6 The excessive visual stimuli of the traumatic event are never represented in Jaar’s work but indexed in abstract form through the use of blinding neon lights or flashes.

The traumatic nature of the image is particularly present in his Rwanda Project (1994–2000) which explores the remnants of the Rwandan genocide. In 1994, a few weeks after the end of the genocide, Jaar leaves for Rwanda where he takes some 3,000 pictures. He spends a lot of time in the company of victims, debriefing survivors. It then takes him six years to process the material, attempting to do justice to events and encounters which on many levels cannot be understood, nor represented. The Real is what cannot be apprehended nor represented, yet what is most sensitive and intimate to the subject, what survives in waiting or as the French say, en souffrance. The Real points towards a failure of representation, a failure which sustains Jaar’s engagement with the subject matter of genocide: ‘If I spent six years working on this project, it was trying different strategies of representation. Each project was a new exercise, a new strategy, and a new failure… Basically, this serial structure of exercises was forced by the Rwandan tragedy and my incapacity to represent it in a way that made sense’.7 It is this failure of representation – undeniable when it comes to the traumatic visual culture of atrocities – that Jaar seeks not only to show and expose but to bring about in the radical interface articulated by his installations. In his visual and material strategies dealing with atrocities, Jaar has made a point to avoid the too easy and banal trappings of empathy which are inevitably attached to the pathos of visual suffering, thus disarming the compulsive identification with the victim which drives the viewer faced with representations of atrocities. This gesture recalls Jochen Gerz’s burial of memorial monuments as well as Claude Lanzmann’s approach to the Holocaust where the scandalous images of the genocide itself were discarded and the simple narratives of those involved privileged. Instead of the visual pathos of suffering or the horror provoked by the sight of mutilated or dead bodies, the viewer is caught and trapped, as in The Sound of Silence, within the historical nature of the ‘document’.

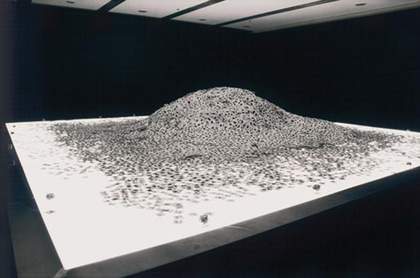

Fig.2

Alfredo Jaar

Real Pictures 1995

© Alfredo Jaar, courtesy Galerie Lelong, New York

Real Pictures 1995 is an installation where Jaar’s Rwandan pictures are not visible but buried and ‘entombed’ in black boxes.8 Every box bears the factual description and narrative of the photograph and the visitor is overloaded with the narratives of genocide which contrast with the minimalist aesthetic arrangement of the scene. The image, buried in its box/tomb, is transformed into a ‘document’ where the image is suppressed and the narrative exposed, like in The Sound of Silence. One of the narratives reads as follows:

Gutete Emerita, 30 years old, is standing in front of the church. Dressed in modest, worn clothing, her hair is hidden in faded pink cotton kerchief. She was attending mass in the church when the massacre began. Killed with machetes, in front of her eyes, were her husband Tito Kahinamura (40) and her two sons Muhoza (10) and Matirigari (7). Somehow, she managed to escape with her daughter Marie-Louise Unamararunga (12), and hid in a swamp for three weeks, only coming out at night for food. When she speaks about her lost family, she gestures to corpses on the ground, rotting in the African sun.

The boxes are piled onto each other, monumental mass graves of various sizes and heights but also archive, and the darkened room of the Musée Cantonal des Beaux-Arts is transformed into a mausoleum and non-place of memory where Jaar’s Rwandan photographic experience rests. Real Pictures is an obsessive monument dedicated to a traumatic encounter between an artist/witness and the people of Rwanda. We now better understand the special connection, identification and tribute to Kevin Carter with his traumatic encounter with the little Sudanese girl: both men have encountered the Real on African soil. Real Pictures is a site of mourning, not only for the victims of the Rwandan genocide captured in the images but also for the artist’s ‘own private Rwanda’. In a gesture similar to Claude Lanzmann who said that he needed to resuscitate the anonymous victims of the Holocaust and kill them a second time in order to accompany them, Jaar revives and buries his traumatic memories, never abandoning them.9 This life-preserving operation, which borders on exorcism, is the very one that might have protected and saved Kevin Carter.

The photo-reporter as witness and predator is often assaulted by those ambivalent memories of helplessness laced with the scopic cruelty of voyeurism, a traumatic disjunction which lies at the very core of their profession. The story of the surrealist muse and Vogue war reporter Lee Miller presents some interesting insights into the psychic drama of the photo-reporter as well as parallels with the narratives of both Carter and Jaar. Miller had photographed, like Jaar in Rwanda, genocidal remains (in Buchenwald); she had also witnessed like Carter the spectacle of a child dying (in a children’s hospital in Vienna). She cabled the following report of the event:

For an hour I watched a baby die. He was dark and blue when I first saw him. He was the dark dusty blue of these waltz-filled Vienna nights, the same colour as the striped garb of the Dachau skeletons, the same imaginary blue as Strauss’ Danube. I’d thought all babies looked alike, but that was healthy babies; there are many faces of the dying. This wasn’t a two months baby, he was a skinny gladiator. He gasped and fought and struggled for life, and a doctor and a nun and I just stood there and watched. There was nothing to do. In this beautiful children’s hospital with its nursery-rhymed walls and screenless windows, with its clean white beds, its brilliant surgical instruments and empty drug cupboards there was nothing to do but watch him die.10

Lee Miller’s account illustrates the ambivalence that sustains the traumatic visualisation of atrocities: the scopic drive (the ordeal of the baby as ‘skinny gladiator’ recalls the cruel spectacles of ancient Rome) is coupled with and inseparable from helplessness (‘there was nothing to do but watch him die’). The witness is compelled to watch the cruel spectacle but is unable to stop the event, nor suspend the voyeuristic gaze as it unfolds. This is what connects, on some level, the psychic drama of trauma with tragedy, this ‘painful mystery’ tied up with what it is to be human.11 Tragedy, in so far as it stages the dynamic forces of irreparable loss which animate the subject, is a ‘negative ontology’,12 something that Jaar’s ‘document’ seeks to objectify from a phenomenological perspective. Lee Miller never ‘documented’ her own trauma and suffering (this would be later undertaken by her son Anthony Penrose), just blanked out her traumatic experience, never talked about the war and became depressive and alcoholic, trapped in the post-traumatic reality of her atrocious encounters. While she shunned therapy, she did manage to survive through a new-found obsession with cooking which literally saved her life but because of its excessive nature still obeyed a compulsive need to obliterate the memories of the Muselmänner and starving children she had watched and photographed.

Alfredo Jaar through the ‘document’ resurrects, objectifies and engages with the archive of his traumatic memories. In Real Pictures, the traumatic memory is both acknowledged and mourned, laid bare within the non-place of the Rwandan archive. The ‘document’ as it appears now also works as a tool and weapon against trauma in the sense that the psychic reality of the event (the Real) is not denied but acknowledged in Real Pictures and ritually buried, a healing gesture which mirrors the work done by psychiatrists working with victims suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), who are asked during psychological debriefings to factually ‘document’ the genesis of the traumatic event. While his Rwandan installations are serialised and obey an obvious logic of compulsive repetition, Real Pictures is an attempt to ward off and lay at rest the post-traumatic content of his Rwandan photographic encounters.

Fig.3

Alfredo Jaar

The Eyes of Gutete Emerita 1996

© Alfredo Jaar, courtesy Galerie Lelong, New York

The most haunting of his works on Rwanda is probably The Eyes of Gutete Emerita 1996. In The Eyes of Gutete Emerita, the viewer is not directly confronted with the atrocities of the genocide but is faced with the eyes of Gutete Emerita, the gaze of a survivor whose narrative has been mentioned earlier and who has been a direct ‘witness to something it is impossible to bear witness to’.13 The aporia of The Eyes of Gutete Emerita is that there is a fundamental disjunction between the narrative of trauma which can be told but not represented (or can only fail in representation) and her gaze which has witnessed the genocide but is unable to ‘show’ it. This disjunction is also present in Field, Road, Cloud where the legendary beauty of the Rwandan countryside does not show any wounds (trauma etymologically signifies wound) nor signs of the atrocities which have taken place. Jaar once again manages to disable and disarm the viewer’s scopophilia by refusing us the obscene sight of the wound – which is in a way refused by Gutete Emerita and even by Rwanda itself. Alfredo Jaar confronts the viewer’s desire and need to see the traumatic wounds with the survivor’s need – be it the Rwandan trees or Gutete Emerita – to live beyond the event. The uncomfortable viewer is left with the impossible task of searching for traces of a horrifying event which was once there but is no longer present. The traumatic gesture is a returning and a revisiting of the event; this is what the viewer both attempts and fails to do. There are no visible traces. Here lies the cruelty of Jaar’s ‘document’ which refuses to show us the special affects and effects of the traumatic event, only the failure of the Real, which is in the end, as Lacan suggests, a missed encounter.14

Gutete Emerita and Kevin Carter both belong to Jaar’s pantheon of missed encounters. Kevin Carter was unable to assist the little girl, something which would haunt him for the rest of his life. Alfredo Jaar, as witness, pays tribute through his work to his own missed encounters with the Rwandan survivors such as Gutete Emerita whose experience of the impossible he can only fail to understand, let alone represent. The traumatic nature of this missed encounter is indexed by the hundreds of thousands of serialised slides of her eyes, heaped upon a white neon screen. The traumatic white neon screen, so present in the work of Alfredo Jaar, indexes the emptiness and excess of absence, the excessive and violent ‘white pain of the absent’.15 The post-traumatic gaze of loss, like the buried images of Real Pictures, is here again sculpted into a mass grave or funerary heap, laid bare within a blinding field, in a gesture which attempts both to revive and bury at the same time. The powerful and haunting nature of The Eyes of Gutete Emerita lies in the shaming gaze of this missed encounter, which is not only a missed encounter between Jaar and his subject, but a missed encounter between the West and Rwanda. It is only through the ‘document’, that the failed encounter can finally be in a way ‘rectified’ – made right – when the viewer finally engages with the missed encounter that is, with the material of absence itself. What Alfredo Jaar manages to conjure within the space of the museum is the very experience of our failed engagement with not only certain images or realities but also the very political fabric that make those realities possible.

Through the ‘document’, Alfredo Jaar has staged the ‘atrocity triangle’ and trapped the post-traumatic gaze. He has re-created and re-orchestrated the missed encounter of the traumatic event which can now be experienced by the viewer in the re-organised and specific time/space of the ‘document’ tailored for the traumatic narrative, which always exceeds and violates the frame of the image and therefore can only fail in representation. Through the ‘document’, Jaar has managed to reprogramme the very mechanisms which sustain the shock dynamics of trauma. The absence specific to trauma – this disjunction between the subject and the event – is conjured in the ‘document’ where the viewer can now engage with the painful reality of this absence, and be present to it. What the ‘document’ achieves on an operative level is to obliterate the space of denial because the artist has emptied the ‘document’ of the shock-value of the wound and demystified the political master narrative. The ‘special affects’ of shock are defused when the visual effects are substituted with the contextualisation of the image/event as ‘document’. If Jaar uses shock tactics in his work like the flashes of The Sound of Silence, these tactics are less intent to shock than to operate a shift in the scopic field. These external excitations act as barrage against the scopic drive of the viewer which is mis-en-échec and disarmed.

What the art of Alfredo Jaar tells us is that we have to move away from the scopic trappings offered by the sight of traumatic images which show and excite but do not explain. The spectacle of these images is costly from a psychological perspective, as the tale of Kevin Carter’s ‘failed mourning’ demonstrates. The excessive and overbearing presence of the traumatic image will trigger a process of impossible denial; they will haunt the viewer and return until they are dealt with, that is acknowledged and mourned. The other danger that the spectacle of these images articulates is apathy (apathy being an excessive response similar to shock and also related to trauma), as Griselda Pollock explains: ‘The more we see what we appear to need to see to believe in their reality, the less we are able to respond affectively to what we are shown. We have become inured to the pain of others in direct proportion to our apparently insatiable need to be shown the horrors of the world and to be exposed to the suffering of others’.16 The ‘document’ provides an alternative to the scopic trap of the ‘atrocity triangle’ and the PTSD shock/apathy continuum by fostering acknowledgement and providing an interface with the missed event, of which the sight of the wound is crucially absent. Instead of the ‘negative ontology’ of trauma, the art of Alfredo Jaar has relentlessly sought to reawaken and affirm a ‘positive ontology’, that is a compassionate ethics of presence, a political consciousness oriented towards being present to those who most need our assistance and protection. Traumatic events such as the Rwandan genocide can and, in this very case, have resulted from our daily or, as Jaar pointed out in Untitled/Newsweek, weekly failure to understand, engage and address certain realities – from our own absence within the political frame. Global events are not foreign, nor exterior to us; on the contrary, as Jaar has relentlessly demonstrated, we are very much part of their fabric. Whether we chose to be absent or present is entirely up to us.