This paper is based on conversations, conjecture and texts exchanged by an artist, Lucy Gunning, an art historian, Jo Melvin, and an archivist, Victoria Worsley. It explores ideas using a mixture of explanatory texts and fragments of both real and imagined discussions about the nature and function of an archive. The archive is seen here as an element in the making of art, as evidenced in Lucy Gunning’s recent work, and as the site of traces of the past in material form, which is explored through Jo Melvin’s work on the Studio International archive held at Tate, Lucy Gunning’s experience of the Wordsworth Trust Archive and Victoria Worsley’s daily experience as a custodian of artist’s papers at the Henry Moore Institute Archive in Leeds.

Lucy Gunning works with film, video and performance, usually in a site-specific context. In 2006 she took a six-month residency at the Wordsworth Trust. The resulting work, The Archive, The Event and its Architecture, comprised a number of elements. The first was an event in the Village Hall of Grasmere, which presented simultaneously all the activities that take place there. The second was a walk up the five peaks surrounding Grasmere, with the walkers wearing mirrors on their backs. Only incidental documentation survives of these two events: a documentary film of the Village Hall event and photographs taken by some of the walkers. A further event was a symposium in the Village Hall called ‘The Archive, The Event and its Architecture’, where presentations were given by Lucy Gunning, Tim Gough and Jo Melvin. The occasion also marked the launch of the accompanying book which reproduced the texts of the speakers.1

In September 2007 Lucy Gunning undertook another residency for two and half weeks at the Philbrook Museum, Oklahoma. This culminated in the exhibition RePhil at the museum from September to December of that year.

Victoria Worsley

Why did you use ‘archive’ in the title of the Wordsworth Trust project?

Lucy Gunning

I had already visited the archive. I knew what was there and I wanted to know and understand it more. I also wanted an opportunity to address the notion of the archive more generally. I used it in the title specifically because I was interested in its relation to the event, to the moment, and its relation to site and architecture. It did not exist on its own in my mind. It was something that I wanted to position in relation to these two other things in order to find out more about its relationship to ‘now’. I wondered whether an event could be an archive, or an archive an event, or whether architecture could be an event etc.

Victoria Worsley

Are you saying that you were looking at how the archive represents the past as opposed to the ‘now’? LG I was thinking of the archive as something in the present that holds documents of the past, and architecture as something with the potential to be of the past and the present, and the event as something in the ‘now’. Obviously, each has a future and becomes a past. I was interested in where all this converges.VW Could you describe why you were attracted to the site of the Village Hall in Grasmere?

Fig.1

The Village Hall Event, Grasmere, 2007

© Lucy Gunning

Lucy Gunning

The Village Hall was a hub of activity and exchange in the village and also a particularly fine example of that sort of building. I wanted to make all the things that happen in there, happen all at once, to try to compound time. Also there was a certain sort of chaos that appealed to me about bringing all these things together. Initially, I thought it would be quite choreographed, that I would choose a character from a Dialect play, and juxtapose this with a Ceilidh caller, alongside bowls or badminton and so on. In the end, it became a much looser event. Partly because when I approached the Grasmere players, they were horrified about the idea of performing on stage while anything else was happening at the same time. I had to work with what people were prepared to do. There was a lot of negotiation and compromise involved. Also in the Village Hall there is a painting by Frank Bramley RA that depicts the rush-bearing ritual that takes place annually in Grasmere. The painting is permanently housed in the hall but behind cupboard doors and only opened on special occasions. We were allowed to have it open.

Victoria Worsley

In bringing all those different elements of the community together you constructed a kind of absurd drama in which nothing is completed, a sampling of village life. How did you view their activities?

Lucy Gunning

There is something very valuable about them in terms of real exchange and contact.

Victoria Worsley

It reminds me of how Hal Foster defines the ‘archival impulse’ where he speaks of recasting lost or outmoded social practice as a type of aesthetics of resistance to an amnesiac society.2

But you were also complicating the heterogeneous nature of the use of the space by interfering with reality, perhaps in a commemorative way, by collapsing them into one time frame. It is almost like a live or time-based version of the Bramley painting. Foster also writes of an archival impulse which desires to ‘connect what cannot be connected … not to totalise so much as a will to relate – to probe a misplaced past, to collate its different signs … to ascertain what might remain for the present … it assumes anomic fragmentation as a condition not only to present but to work through, and proposes new orders of affective association … even as it also registers the difficulty, at times the absurdity of doing so.’3

Lucy Gunning

It was commemorative but in, and of, the present. The past makes up part of that ‘present’, as does the future. It was absurd, skewed by all happening at once. It was both part of everyday experience and subtly removed from it at the same time.

Fig.2

The Mirror Event, Grasmere, 2007

© Lucy Gunning

Fig.3

The Mirror Event, Grasmere, 2007

© Lucy Gunning

Victoria Worsley

Could you describe what happened with the mirror event and its relation to the Village Hall event?

Lucy Gunning

The Village Hall event was held on Saturday, 31 March 2007, between 2–5pm. The following morning there was another event which involved a group of us meeting at the Village Hall at 10 o’clock to collect mirrors that I had bought from local second-hand shops and adapted so they could be worn like rucksacks. We assembled on the village green to have a photograph taken. The Village Hall event had been about evoking a live archive: there was a whole range of things to see and do there. The following day was quite a different experience. There were thirteen of us wearing the mirrors. We split up in different directions and walked up the five peaks nearest Grasmere. Three of us went up Stone Arthur, two of us went up Helm Cragg. There were odd numbers of us, dispersing in different directions. Other people walked with us – they were quite long walks. It took two and a half to three hours to get up to the tops of the peaks and back down again. During the walk what we were walking past was reflected in the mirrors. If you were walking behind someone who was wearing a mirror, it was as if a film was being played back to you, though it was a film that was not being retained.

I was interested in juxtaposing this piece with the Village Hall event precisely because of its instantaneousness and the way in which even the few photographs do not really capture the event. When we got to the tops of the peaks we did quite a childish thing and started flashing the mirrors at each other. There was something extraordinary about that because sometimes the flashes of lights from the mirrors were 20 or 30 foot wide. For an instant, it was if reality had been erased: it was just white light. The other thing that interested me about it was that there was a sense in which you could not ever experience the whole – you were only part of something. I saw mirrors on top of two other peaks. There were another two that I could not see. None of us could see all of them. There was an impossibility of capturing and documenting it as an event: it had to be live. I was interested in that as a defiance of ‘the archive’.

Fig.4

The Mirror Event, Grasmere, 2007

© Lucy Gunning

Victoria Worsley

The photographs give a sense of how enchanting the event must have been.

Lucy Gunning

They were rather a random part of the experience. People just happened to have cameras on them. I had my camera but took very few photos.

Victoria Worsley

But are you glad that there are images?

Lucy Gunning

Yes, I am. But they are only an approximation of what happened

Jo Melvin

Maybe people who were walking on those hills, who were not anything to do with the event, saw flashes of light, and the memory stayed with them. But there is something about the fact that it happened, and that it was not specifically documented by Lucy, that gives it an added richness in how it manifests itself, not just through the photographs, but through the telling of it. Through Lucy’s re-telling of it and through other people’s telling of your telling.

Victoria Worsley

What is the difference between Lucy speaking about it and seeing the photographs? The images are the only material trace along with the written description.

Lucy Gunning

One becomes more like a myth.

Jo Melvin

A story.

Lucy Gunning

Yes, and the other one is a document – but it is only a partial document.

Jo Melvin

But the story about it becomes like the first fiction about it.

Lucy Gunning

I decided not to film it because I wanted a different relationship from what had happened in the Village Hall. Yet when the mirror event was happening, I was aware it could have looked great on film and that something was being lost by not doing that. At the same time, I wanted to put the emphasis upon it happening, on the experience of it happening, and on the people who witnessed that. Something very ephemeral and word of mouth happens as an extension of that. It reminds me of the Dialect plays, which are why the Village Hall was built in Grasmere in the first place. The plays are just local stories that were collected because a few people wanted to document or capture the local dialect that was being lost. They were written as a way of preserving that for us.

Victoria Worsley

Were you creating an archive of the community, in the same way as the Dialect plays?

Lucy Gunning

What I was doing was happening through the archive rather than about the archive directly.

Victoria Worsley

Hal Foster defines how archival art works ‘serve as found arks of lost moments in which the here-and-now of the work functions as a possible portal between an unfinished past and a reopened future’.4

Fig.5

The Philbrook Museum, 2007

© Lucy Gunning

Fig.6

The Barcelona Pavilion, 2007

© Lucy Gunning

Lucy Gunning

Another project completed since the Wordsworth Trust residency titled RePhil also seems appropriate to this discussion.5

I was invited to exhibit at the Philbrook Museum in Tulsa, Oklahoma. It was in a very particular context of an Italianate villa that had become a museum. I could not visit the museum before exhibiting there, and so I did as much research as I could – for example, I read the biography of Waite Phillips who donated the museum to the City of Tulsa. The villa was built around 1928, and I was amazed that this was the sort of building that he wanted to build. I had been looking at Mies van der Rohe’s Barcelona Pavilion also built in 1928, and I decided to go and film it with the intention of showing it in the museum. I also filmed a solar power station in Seville wanting to make connections between this and Waite Phillips being an oil magnate and Tulsa being a city that exists because of the oil industry. In his biography I had come across a photograph of Waite Phillips, wearing a Spanish costume, that was also taken in 1928.

The work became about borrowing ‘culture’, institutional critique, and the particular history of that museum. The project involved me working with their collection, moving things around, making juxtapositions and inserting my own work. In the end I made twelve interventions. I was there two weeks prior to the opening. I spent the first week looking at the collection and talking to the people who worked there. I entered a process of discussion, whilst also being very aware of my position as an artist within that context. I went around the museum with as many people who worked there as I could, and through this process I had very different experiences of the museum. There was a security guard who let me into all the rooms that you are not meant to go into – everything from the boiler room to the attic or the basement or storerooms. I had access to places that visitors were not allowed in to. There was a balcony that existed between two rooms that had been bedrooms but the public were not allowed up there because the tiles were broken.

Fig.7

Lucy Gunning

RePhil, showing a plinth with the image of Waite Phillips in Spanish costume

Philbrook Museum, Tulsa, Oklahoma, 2007 © Lucy Gunning

Jo Melvin

So you were finding the hidden spaces, inaccessible to the normal visitor of the museum. All the various conversations you had about people’s impressions of the museum were triggered by the same place but had completely diverse feelings, senses, memories, and reflections.

Lucy Gunning

At one point I wondered if the work should involve recordings of these stories, but I was not recording them and I needed them to just be what they were, a spoken exchange. These conversations and stories determined what I discovered and what I interacted with. I became very informed about the museum. It was an investigative process and much of the information I gleaned remained tangential to the final work but I could not have arrived at the work without it.

Fig.8

Bathroom/store at the Philbrook Museum, 2007

© Lucy Gunning

Lucy Gunning

When taking photographs of hidden spaces, I came across a bathroom. This was one of the few spaces within the museum that was left intact from when the family had lived there and it had been a home. It had beautiful Spanish tiles on the walls, but was used as a store for AV equipment. There was also an advertising board for the Philbrook Museum on a shelf, and behind it was a mirror.

Jo Melvin

This image seemed like the opposite of the bathroom referred to in the Studio International archive. This archive, which I have inhabited for years, comprises the editorial papers of Peter Townsend during the time he was editor of Studio International. It contains original articles for publication, corrected copies, galleys and correspondence related to publications, photographs and original art works, provisional ideas and plans, agendas for committee meetings, layout page pulls, a wealth of unsolicited correspondence, lists, memorabilia and personal notes.

William Townsend, Peter’s brother, was a painter who taught at the Slade. He kept a journal. The entry for Tuesday, 1 February 1966 reads as follows:

Lunchtime to see Peter’s new office on the top floor of a house in Museum Street… Sun coming in across the street, bathroom turned into a library … but he is working too hard, meetings and getting contributions, long conversations, taped discussions out of all sorts of people – with enthusiasm and enterprise. Told Tony not to work him too hard but he said ‘it’s all his doing, that’s the way he is.’ This should have worked out as a part-time job…but I can’t ever see it being that.6

In the Studio International archive there is no documentation of the ‘library in the bathroom’, no photograph. But reading this entry led me to ask assistants about it. Charles Harrison recalled the loo on the stairs in the corner and John McEwen remembered the crowded bathroom, a cramped dual-purpose space.

Lucy Gunning

It was only by chance that you came across that.

Victoria Worsley

It exists mainly as something of memory, whereas Lucy’s bathroom existed physically but acted as a store both for AV material. You have both recovered a hidden story that was waiting to be revealed.

Jo Melvin

Exactly, it’s just by casting light on something. There was another connection between the bathroom and the archive which was about cleaning up.

Research is about getting the dust out from the corners. How far do you go when you are trying to make some kind of investigation? How many conversations do you have with how many different people? How far do I go with trying to pin down a certain decision that Barbara Reise made from different pieces of paper? I would not want to clean it up to make it into a seamless story but to bring it out so that it’s visible, rather than shoved under the carpet.

Victoria Worsley

I find the more I clean, the more I notice the dirt. With research, the more you find out, the more you realise you do not know. It is like an endless funnel drawing you in.

Jo Melvin

Dirt is interesting as a metaphor but it also has a physical presence in archives. I have been recently going through lots of black bags from the Studio International material which Peter had held back until his death. That forty-year-old dust seeps into your skin; even when you wash your hands they still feel painful and it lasts, it really does last, two or three days. The dust and the dirt is so much a part of it, you cannot escape from it. Apparently in France, a grubby archival document is referred to as ‘in the English condition’, which means dirty.

Victoria Worsley

When I receive an archive and it is in a mess, it is so exciting. We sort it, clean it, package it, order it and catalogue it and the frenetic energy of the original disorder goes.

Lucy Gunning

Yes, that is the whole thing about cleaning, creating the order and then the disappointment. I remember once spending ages cleaning a lime-scale stain off a sink and then missing it and thinking I really wish I had not done it. The cleaning erased time and experience.

Victoria Worsley

Is dirt dangerous or creative?

Lucy Gunning

In the process of video editing, I sometimes become more interested in the footage I have been cutting out. Once when editing a text – it was an interview that was transcribed – I became interested in the words that I had taken out. I made a list of them and that became a piece of work.

Jo Melvin

All the omissions?

Victoria Worsley

Yes. What you decide to keep and what you leave out concerns the value placed on what is remembered.

Lucy Gunning

I was interested in what was taken out of the text, over and above what it was taken out of. It became independent of the original thing. It became something in-between.

Jo Melvin

The in-between is an archival problem. How you do authorise those ellipses? Taking the omission and making it a positive thing changes everything.

Lucy Gunning

It becomes the thing.

Victoria Worsley

Archives are bits of paper. They are not the thing itself. They are produced by the life lived, which they now stand in for.

Jo Melvin

This is what Lucy was talking about in not documenting the event with mirrors. It is precisely that moment of the flash of light that is the moment of living. When you are engaging with the past through an archive you get into a relational exchange with material, and sometimes you have that momentary flash. Suddenly, the past is gone but it has triggered a moment of understanding in the present.

Victoria Worsley

In an institutional archive that present moment is mediated through the archivist’s intervention (although we are supposed to remain objective). Where there is an original order we will preserve it but where there is chaos we will construct an order.

Jo Melvin

Peter’s files did not exist, and so I have made a fiction of them. He had files for each month’s issue but they would be used again. So February 1971 would be written over the top of December 1970. Some of December 1970 would be left in it and some of April 1971. I took out all the material for each issue to create a file.

Lucy Gunning

But is not that really interesting when it is all muddled up? Should not the original state be recorded somehow?

Victoria Worsley

Archivists do preserve what we term ‘the original order’ of documents, where it exists. But then we catalogue, number and present the material in specialist preservation files, boxes and sleeves. In a way we are making the past perfect in the files.

Lucy Gunning

Sanitising them. It sounds horrible. It is like what the National Trust does to the landscape. There is something medicinal about it.

Victoria Worsley

The cleaning up is necessary so that you can preserve it and present it for the future. Can you just talk a bit about your experience of going through Peter Townsend’s black bags?

Jo Melvin

It was a very strange experience because the black bags contained the stuff that he wanted me to go through and put into some sort of sensible order. I have saved it all, but it is difficult because some is extremely intimate. You get a juxtaposition of situations, some you may already be aware of. Then there follows a whole layer of different pieces of information … who Peter was seeing at the time, what his obligations and commitments were, his frustrations of not receiving the subsidy for the magazine, who he was meeting for dinner and how much wine that person had or did not have …

Victoria Worsley

Are these bits of information in a diary?

Jo Melvin

They are in different forms. Some of them are on bus tickets, some are on memos. He used those little red notebooks; they were his diaries. They include everything from free writing to interview notes, to lists of to-dos, to costs and so-and-so’s ‘a bloody arsehole’, everything. The over-riding feeling is one of responsibility and also a strange kind of guilt. In a sense, you are in someone’s head, which can be quite overbearing at times. You also need to work out what material you can use and what you cannot because it might offend its creators. For example, the reactions of Sol LeWitt and Lawrence Weiner to Joseph Kosuth’s publication of ‘Art after Philosophy’.

LeWitt made a little stamp which said ‘BULLSHIT’ and both he and Weiner used it to stamp ‘BULLSHIT’ over things.7

Lucy Gunning

What did they used to stamp? The proofs?

Jo Melvin

No, not the proofs because they would not have seen the proofs. Kosuth referred to Weiner and LeWitt in the article. The article triggered a load of letters, some stinking, about Kosuth’s position that continued in Studio International for about two years. Douglas Huebler sent a letter, shortly followed by a postcard to Charles Harrison, the assistant editor, saying please do not publish it, even though the letter had been sent to the printers. He said, ‘even though I feel it, I don’t want it exposed’. The bullshit stamp was printed on letters and miscellaneous things circulated to Peter and Barbara Reise.

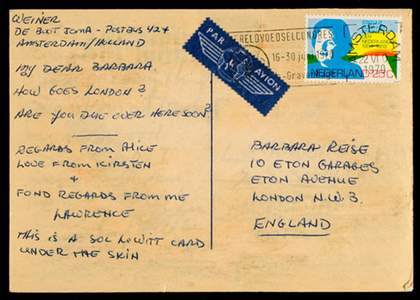

Fig.9

Back of a postcard from Lawrence Weiner to Barbera Reise postmarked 16 June 1970

Courtesy Barbara Reise Archive © Lawrence Weiner

Fig.10

Front of a postcard from Lawrence Weiner to Barbera Reise postmarked 16 June 1970

Courtesy Barbara Reise Archive © Lawrence Weiner

One miscellaneous item was a beer mat, stamped ‘BULLSHIT’ at the top. Peter used it as a list of things to do – and they’re all under that heading! If I had not seen Reise’s correspondence, there would have been no way of knowing where the mat had come from. Reise was a contributing editor and friends with many artists. Sol LeWitt sent her a letter that decried the politics of the art circle Kosuth had described in the article, and he stamped the word bullshit over the whole letter. He also sent a postcard to Lawrence Weiner. The picture showed a car like an Italian Futurist’s motor car, and he had stamped bullshit on it. Lawrence Weiner reused that postcard. He stuck a piece of paper on the back and sent the card to Barbara Reise. So the bullshit stamp ended up in a different form with Barbara.

Victoria Worsley

The personal nature of the archive gets lost when it goes into an institution. An archive is all about social interactions. Jo, you almost became Peter’s memory bank through working with him and on his archive. When you read the more personal material how did that relate to your view of Peter as you knew him?

Jo Melvin

I knew a lot of his personal stuff. The archive serves as a testimony to events and to the relationship between colleagues. It traces evolving friendships. Archive stories testify to occasions that surrounded the magazine’s publication, as well as documenting particular events. The stories are not intended for publication, but are like confessionals from one time to another. The silent witness becomes a voluble interlocutor.

Victoria Worsley

An archive remains in the present tense of its creation and when you read it you are re-enacting that present moment. Often an archive will be heavily edited before it reaches the archive institution. On many occasions, I have been aware that personal and intimate records have been destroyed and through that you lose the sense of personal networks between people. All those interconnections, those really important things that happen between people, how people support each other, and how events happen.

Lucy Gunning

There was a group of love letters between William and Mary Wordsworth that were not discovered until, I think, the late 1970s. They were published in 1982, and threw a completely different light upon their relationship. Prior to that, people thought that Wordsworth’s marriage was loveless. Those letters revealed a very loving relationship that grew and developed over time. It changed a lot of people’s views.

Sometimes I would be reading in the library at the Wordsworth Trust and think why am I reading this? Here am I in 2007 sitting here reading about the relationship between William and Mary, thinking that I am going to find something out, or that it is going to have some bearing on my existence. I was 100 yards away from where it took place and at times, the weight of the past felt greater than the present. I had contact with these people through the archive and it felt like everybody was dead. It could be quite depressing. Things would start to get a bit blurred and I would wonder where am I in all this, why does the past become more important than the present? I could not stop questioning my relationship to the material, and ask whether I should be reading it, because some of it was too private.

Jo Melvin

But I think there is a big difference between gossip and anecdote. An awful lot of the material that I engage with is anecdotal and this can be an immensely poignant form of information. It sometimes borders on being a piece of gossip, but often it is incidental information that puts my reading of something into a very different light. I think the story about the bullshit stamp is an anecdote that explains why so many of those artists were wringing their hands over the publicity that Kosuth was getting.

Victoria Worsley

Gossip is a difficult term as it puts a negative inflection on all the private and intimate papers in an archive.

Lucy Gunning

Is there a moral dilemma, an ethical dilemma?

Victoria Worsley

Some material is covered by Data Protection and so anybody who is living is protected. If there is something libellous or intensely personal, you would contact that person before you let it go to the public sphere. Sometimes there are things in the archive about people’s relationships that even close families are not aware of and this kind of information could be incredibly destructive. You have to tread very carefully.

Lucy Gunning

It is quite a responsibility.

Jo Melvin

That is what I was talking about when I mentioned the guilt.

Lucy Gunning

But our relationship to this stuff becomes so important because it outlives people.

Victoria Worsley

Archives are not dead. They are not just the material traces of the past. You can bring them to life, and write creative stories that resonate with the present.

Jo Melvin

I do not want to go back in time and be a fly in the wall.

Victoria Worsley

You do not want to be Peter Townsend and live his life, because then you are living through others.

Jo Melvin

But there are moments of phobia when I think I am.

Victoria Worsley

Do you keep an archive Lucy?

Lucy Gunning

I would not call it an archive. It is very haphazard and I would probably say that initially I kept everything and as time has gone on, I have had to chuck things out. It is to do with space. I could not keep everything. Earlier documents have been kept, and as time has gone on I have probably got better at documenting. But I have not kept anything in any order or kept it because I think I ought to keep it. It has just turned out that way.

Victoria Worsley

Some artists are consciously documenting.

Lucy Gunning

Yes, I know they are. I do not have that relationship to it because I am more interested in the present.

Victoria Worsley

I feel Lucy has a resistance to the notion of archive.

Lucy Gunning

Probably! I think I have a resistance or ambivalence – I am like that about a lot of things. I am also a bit of a sceptic. I do not like to have everything mapped out or put in boxes and cleaned up for me, although I know it is helpful and I enjoyed the journeys I took in the Wordsworth archive – one minute I could be looking at a Dialect Play and the next a book with an inscription by Wordsworth or Coleridge. I can understand both the reason for it and the wonder of it. But I am still sceptical about my relationship to it. My interest in it has evolved out of how I respond to the context in which I am making work, and so it is an extension of site and space, where time has become important.