Portraiture refers to many things: a realistic portrayal, a memento, a memorialisation, a signifier of lineage; it can also reinforce the privileges of ownership and heritage.1 While the subjects of portraits might range across class and gender, certain figures – black subjects, for example – when incorporated into portraiture have had different roles to play. Included as accessory, decoration and property, black figures inhabited a central role in many portraits, not as subjects but as embellishments that enacted another sitter’s importance.2 To depict a subject in Western art as black has often meant to denigrate. From caricature to cipher, art history has a long genealogy of representing non-white subjects in ways that articulated their antithesis to ideals of whiteness and its attendant notions of beauty. It was this history that black intellectuals, writers and artists like Phyllis Wheatley, Frederick Douglass, Sojourner Truth, W.E.B. DuBois and Laura Wheeler Waring focused on dismantling. Using image and text they helped shape the field of African American art by articulating the powerful possibilities that came with the ownership of representation.3 Claiming the right to self-representation has often been bound up with claims for social and political equality by African Americans in the United States; agency and representation – or ‘vision and justice’, as art historian Sarah E. Lewis has more recently termed it – go hand in hand.4 If portraits could materialise this claim to humanity and equality through subject, they also did so through their composition. These artists and intellectuals sought to reconstitute black bodies – once commodified – into new visions of self-making.

As cultural historian W.J.T. Mitchell has explained, ‘race is not merely a content to be mediated, an object to be represented visually or verbally, or a thing to be depicted in a likeness or image … race is itself a medium and an iconic form – not simply something to be seen, but itself a framework for seeing through or … seeing as.’5 Race, in other words, is not merely a representation: its construction and its meaning is framed in the technique, the paint, the composition of images and it is embedded in the process of looking and understanding. Since at least the eighteenth century, black American intellectuals – including those mentioned above – have sought to dismantle seemingly self-evident relationships between style and recognition shaped by discourses of race, science and economics.6 These intellectuals aimed to decouple assumptions around visibility and recognition, to pry open aesthetic categories and use them to reformulate black bodies in ways that put them outside normative meanings of race, and its formation, in the United States.

As a genre, portraiture draws attention to an individual’s specificity. It actively highlights a subject’s exceptional or unique characteristics as they wish to portray them. Within the constructs of racist discourse, blackness was both a specific form of difference, used to highlight ideals of whiteness as normative, and an indicator of generalised constructions of identity. In this sense we might consider blackness as something that verged on the iconic: its form resembling its meaning. Cultural theorist Nicole Fleetwood argues that race ‘modifies and makes iconic … images in public culture’.7 Histories of race construct blackness as a pre-defined text, meaning black bodies in American society are always already understood in specific ways. According to Fleetwood, it is these constructions that also underpin the logic of ‘racial iconicity [which] hinges on a relationship between veneration and denigration and this twinning shapes the visual production and reception of Black American icons’.8 The racial icon is, then, a figure who is both exceptional and familiar, who comes to stand in for the collective and the individual. An icon’s emblematic quality must register these shifts of meaning in its form: it calls attention to its specificity while also standing in for a larger body of knowledge. In early Christian religious traditions, an icon was more than an image: it was a form of veneration that directed a viewer’s worship. It was a mode of prayer; it produced God; it acted in and on the world. Today, an icon is more like an image: a representation ‘imbued with significant social and symbolic meaning so much so that it needs little explication for the reader to decode it’, argues Fleetwood.9 As art historian Richard J. Powell observes, there is also something iconic about Barkley L. Hendricks’s work in the way it reflects to contemporary viewers the spirit, expression and effect of the 1970s. The clothes, the pose and the attitude combine to illustrate the proclamation by musician James Brown and the wider black power movement that ‘black is beautiful’.10 But Hendricks’s purposeful renderings of black (and sometimes white) style, while ‘fall[ing] into [a] narrative that has been a part of a time period’, as he described it, also go beyond simply expressing the feeling of a particular time.11

Modern iconicity

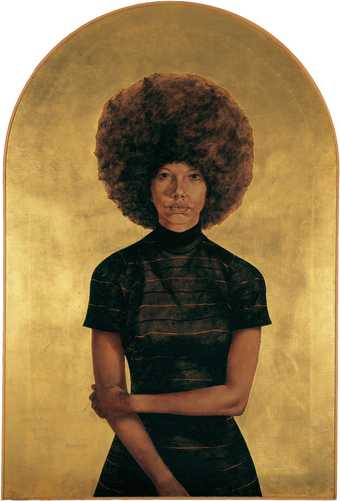

Fig.1

Barkley L. Hendricks

Lawdy Mama 1969

Oil and gold leaf on linen canvas

1365 x 921 mm

Studio Museum in Harlem, New York

© Estate of Barkley L. Hendricks. Courtesy of the artist’s estate and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York

Hendricks’s Lawdy Mama 1969 (fig.1) is a beautiful portrait of his cousin Kathy Williams and is named after a song by Nina Simone, a musician they both liked. Williams is set against a gold-leaf background. Her natural afro – a halo-like shape that frames her sharp features – is itself framed by the rounded upper edge of the canvas. Its sitter is often misidentified as Angela Davis or Kathleen Cleaver, both of whom were involved in the Black Panther Party.12 This painting clearly draws on Byzantine artistic traditions – the gold leaf, the flat background, the halo – to create a modern day form of the icon. Here Hendricks has brought these shifting histories of the icon together to reinforce each other: the iconicity of Lawdy Mama stems from his aesthetic choices (this was one of his early experiments with gold leaf), and Williams represents a certain set of cultural attributes – associated most powerfully with her natural hairstyle – that remain significant in contemporary society.

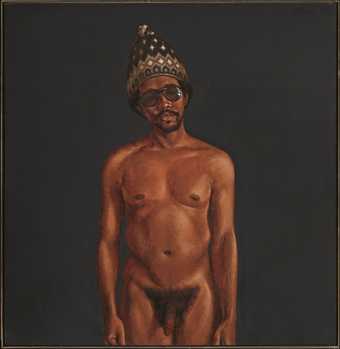

Fig.2

Barkley L. Hendricks

Family Jules: NNN (No Naked Niggahs) 1974

Oil paint on linen

Support: 1681 x 1832 x 35 mm

Tate L02979

© Estate of Barkley L. Hendricks. Courtesy of the artist’s estate and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York

The argument here is that Hendricks does not shy away from foregrounding the spectacular individuality of his sitters, yet he is careful to construct their iconicity through the formal conventions of artistic representation, and to draw attention to this construction through his own formal innovation and his sitters’ self-presentation. In his depiction of his friend George Jules Taylor in Family Jules: NNN (No Naked Niggahs) 1974 (Tate L02979; fig.2), for example, Hendricks draws on the recognisable art historical frameworks of the nude and the eighteenth-century European grand manner portrait to present an expression of black masculinity that challenges audiences, then and now. Consider the painting’s title: Family Jules: NNN (No Naked Niggahs). Hendricks describes the evolution of the title in this way: ‘One of my friends said once, when I told him [about a nude that I had in a show] … he said, “hey man, you know, those white people don’t want to see no naked niggahs”.’13 While this quotation on the one hand might refer to the respectability politics around nudity and representation (something I attend to in another part of this In Focus), it also highlights Hendricks’s awareness of the predetermined structures that frame how viewers see through, or look at, race.14 It foregrounds his understanding of the ways black bodies are always already understood, and makes clear his refusal to create work that is only concerned with rewriting these perceptions. Certainly, we need to understand how this portrait of Jules emerges from the intersections of histories of portraiture in the fields of art history and African American studies. But we must also try to comprehend how the work recuperates and resituates the black (male) body on its own terms, beyond these discourses. For as Jules asserts his right to representation, Hendricks asserts his own claim to represent: he does not set out to insert black bodies into familiar frameworks but to challenge the frameworks themselves. It is therefore crucial not to see his referential process as imitative, but rather as a strategy for disassembling the chains of association that have fixed blackness and black artists in place, so to speak. By compelling viewers to work through a range of aesthetic references in order to decode Family Jules and understand its stylistic innovations, Hendricks directs our interpretation beyond the surface of the recognisable, to reframe art historical conventions and their assumed meanings. Before examining this further in the context of Hendricks’s visual quotations and his play with processes of recognition and frames of reference, it is helpful to understand how his artistic style was formed through his training.

Education, influences and ‘the burden of representation’

Born in 1945, Hendricks grew up in the North Philadelphia neighbourhood of Tioga. His parents, transplants from Halifax Country, Virginia, had – like so many other black southerners – made the move north during the great migration of the 1930s and 1940s. A beneficiary of Philadelphia’s community and youth programmes, Hendricks was always sketching and his fascination with the sartorial splendour of the black community emerged from his North Philadelphia years: the neighbourhood basketball court, church, the schoolyard and the street.15 In other words, from an early age Hendricks painted what he observed taking place around him. His models were people he saw on the street, people he was familiar with and perhaps even knew personally, as they would continue to be throughout his career.

When asked how he decided to become an artist, Hendricks first of all explained: ‘I was born an artist, and school was like a gem-polishing experience. I was a gem and I needed some polish. So I’ve been involved in art my entire life, unlike people who go into a profession. You know, I’ve been involved with art before I even had a memory of what an artist was … I was always scratching on something.’ This early passion was encouraged throughout his education:

When I got to a schooling sort of situation, I had teachers that supported that by giving me supplies … In [Elizabeth Dunne Gillespie] Junior High School I had a teacher that was sympathetic to the arts and became sympathetic to me. His name was Freddie Bacon, and when I got to Gratz [Simon Gratz High School], there were several teachers that were also supportive and sympathetic. And credit has to be given to them for helping to further aspects of my education.16

These early experiences also shaped and developed his representational technique, alongside his love of jazz:

I remember vividly, a good friend of mine whose brother was a bit older and he borrowed his brother’s Coltrane record and brought it into class. And we were to [make] some illustrations from that particular pressing, which always comes to mind [as] it’s one of the seminal musical pieces that still sticks with me. [So] being inspired to do record album jackets [for] music that I like. And starting illustrations, to develop basic skills, were part of the areas that I experienced in I think, it [was] Ruth Bridges’s class. And then I had another teacher whose name was Mary Higgins and she helped to give me a free rein in terms of direction, and when I got home, I followed through with the development of my representational skills … I stuck with realism, or representational imagery in the face of so much of the commotion of abstraction [because] I saw abstraction as not high enough.17

But Hendricks also attributed his interest in representational imagery to another experience he gained in Philadelphia, where he found a correlation between the process of abstract painting and the kind of manual labour he would undertake for his father on weekends. He explained:

Well, I’m talking about this for the first time because my father was a contractor and we did everything imaginable to a house, from tearing it down to building it up and painting and doing all manner of home repairs. And [sometimes we had to] rid the houses of junk. I remember taking a sledgehammer to a Wurlitzer. So [my father] says, ‘Take the hammer to it and bash it up and throw it out on the truck’. So after doing that kind of work as well as painting and once you got done you had to clean your brush, I remember you know, just taking brushes and going all up and down a particular wall to clean the brush. So to me the whole area of abstraction didn’t develop my skills. So therefore I didn’t follow that.18

Hendricks’s paintings materialised amid the competing aesthetics of a range of artistic movements, from conceptualism to pop art, and at a time when the relevance of realism was being called into question.19 Yet his realism challenged the tension between abstraction and the representation of the figure that characterised the development of twentieth-century modernism and the avant-garde aesthetics of the 1960s and 1970s. The distinctions between realism and abstraction have also been used to highlight the boundaries between art and politics as they emerged in the context of the Black Power Movement and the black arts movement.20 However, as scholars of the period continue to remind us, reinforcing these distinctions has sometimes meant that there is an implicit depoliticisation of those artists who did turn to non-figurative art making, and an automatic politicisation of those who did not.21 Such distinctions continue to marginalise African American artists in relation to non-representational artistic movements. They also limit the meanings of black art in general as somehow only concerned with identity: a limitation that Hendricks was both aware of and which he vociferously argued against.22 Scholars are now increasingly critiquing this distinction to broaden our conception of how black artists were involved in a range of aesthetic movements and political debates of the time.23 In doing so they are challenging conceptions of how art is, and is read as, political, while also perhaps re-evaluating what the word ‘political’ means in relation to art making.

Central to this rethinking of the period is a critique of what some scholars have called the ‘burden of representation’, in which African American artists are seen by both black and white communities as something like spokespeople for their race.24 As with all scholarly reformulations, the tendency might now be to oversimplify and delimit what African American representational painting can do, as the avant-garde innovation of non-figurative artists is resituated in the field. Hendricks’s interest in figuration, especially in Family Jules, moves across many of these debates. As he has explained, making representational art during the late 1960s and the 1970s was not, for him, a political move or an attempt to express a racial identity, but something more experimental that allowed him to explore the material possibilities of paint as a form of communication and (self-)expression.25 His commitment to the figure also developed from a method of observation that was interested in the body as material, form and surface. His figuration draws on aspects of abstraction in order to convey this effect, as will be shown elsewhere in this In Focus in particular relation to Family Jules.26

Hendricks was accepted to the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts (PAFA) in the autumn of 1963.27 He entered PAFA during a period of social change and racial anxiety. Earlier black graduates – notably Raymond Saunders – had challenged some of the philosophical ideals of the school and it was in the wake of these debates that Hendricks began his training, along with two other black students: Craig Blake and James Brantley (the subject of Hendricks’s painting J.S.B. III (James Sherman Brantley) 1968, Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia).28 At PAFA he was introduced to drawing from the nude model, and the traditions of painting that emphasised colour, handling of paint and figuration. This training was reinforced by Hendricks’s travel opportunities. He was the first African American artist at PAFA to be awarded two consecutive travel grants: the William Emlen Cresson European Traveling Scholarship and the J. Henry Scheidt Traveling Scholarship. With these awards Hendricks was able to spend successive three-month periods touring the world, studying collections and refining his technique. During the first trip in 1966 he travelled through western Europe, including England, France and the Netherlands. His second trip in 1969 took him to North Africa, including Morocco, Tunisia and Egypt. These occasions were educational and provided fresh inspiration, as Hendricks explained:

Once I won the European travelling scholarship and went to Europe, I had an opportunity to see all the major museums and that kind of rocked my socks … the Louvre and the Prado and the Vatican. And what I saw in terms of painting there, I felt that if you could have a Rembrandt or Caravaggio on the wall, you can have [a] Hendricks? I wasn’t trying to copy anything that I saw. There were lessons to be learned that I could use my own vocabulary, visual vocabulary, to deal with certain areas of extension. That area was in the fourteenth, fifteenth, sixteenth century. Well, I’m not living in the fourteenth, fifteenth or sixteenth century. But I certainly can take lessons from them in terms of how I want to handle my living in the late-twentieth, early twenty-first century. And there were artists that I learned mighty lessons from. Moroni was one of them. I mean, I loved his stuff. And there [are] a number of other artists that were essential in adding to my way of handling the paint and the desire to develop skills that would service whatever direction I wanted to go in.29

Building up an image bank was important for Hendricks in developing his technical skills. He remembers ‘There are some images in, I think the Uffizi and also the National Gallery in London … there are some Moroni images where the figures are in black and if you get close enough, you see just a faint image of white, in terms of giving the illusion of form. But if you step back you won’t see it but you still get that area of volume and that was one of the lessons that I learned from dealing with the contour of the form and working with black.’30 We see these experiments in his depiction of Jules’s black cape in George Jules Taylor 1972 (National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.), for example, but these lessons are also extended in Family Jules, where this illusionistic effect is dispersed across the surface in the creation of its textured allure. Like the old masters who inspired him, Hendricks was a great observer: of people, of architecture and of cities. As he travelled he collected memories in the form of photographs, some of which he would return to in other paintings such as APBs: Afro Parisian Brothers 1978 (Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven), and some of which we see in Family Jules – the tiles on the wall for example, which were copied from photographs he took in Morocco.

Fig.3

Barkley L. Hendricks

Brown Sugar Vine 1970

Collection of Dr and Mrs John T. Williams Sr

© Estate of Barkley L. Hendricks. Courtesy of the artist’s estate and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York

Graduating from PAFA in 1967, Hendricks established a painting studio in downtown Philadelphia while completing his military duty – a four-year attachment to the New Jersey National Guard – and working full time for the Philadelphia Department of Recreation. Between 1967 and the beginning of his MFA studies at the Yale School of Art in 1971, Hendricks featured in several prominent exhibitions, including the Philadelphia Civic Center exhibition and two solo exhibitions in Philadelphia, one at the Philadelphia Arts Alliance (December 1968) and another at Kenmore Gallery (1969). The result of this exposure led to one of his ‘black on white’ canvases, Miss T 1969, being purchased by the Philadelphia Museum of Art, and to his inclusion in the controversial 1971 exhibition Contemporary Black Artists in America at the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York. His contribution – the nude self-portrait Brown Sugar Vine 1970 (fig.3) – is conceptually loaded yet irreverent, and reveals Hendricks’s confidence and comfort with manipulating the human form.

By the time Brown Sugar Vine was exhibited, Hendricks was already halfway through his MFA at Yale. Operating between New Haven and Philadelphia – where his gallery (Kenmore Gallery) and family were located – meant Hendricks remained relatively separate from the political protests and boycott that surrounded the opening of the Contemporary Black Artists in America show.31 His arrival at Yale, however, had coincided with New Haven’s ‘battles between law enforcement, protesters and many of its African American citizens, stemming from the widely publicised arrests and murder trials there for several Black Panther Party members’, according to Powell.32 Within this politically charged atmosphere, Hendricks took classes with Robert Farris Thompson, William Bailey, Tom Brown and had sessions with Josef Albers, whose formal interests in colour aligned with Hendricks’s own experiments. He also had classes with the photographer Walker Evans – an important factor in the development of his own photographic practice, as is discussed in another part of this In Focus.33 Although his aesthetic tendencies might have seemed to align with artists like Alex Katz, who was an instructor at Yale, it was Bernard Chaet with whom Hendricks connected most. Despite their very different aesthetic approaches, they shared some philosophical approaches to painting, and Hendricks was awarded a painting assistantship with Chaet.34 Yet was the photography students rather than the painters to whom Hendricks felt most connected at Yale, mostly, he has stated, because of the focus on abstraction among his fellow painters.35 Hendricks continued to develop his unique approach to the figure, gaining direction from his teachers and extending lessons learned from his European sojourns.

Challenging portraiture’s conventions

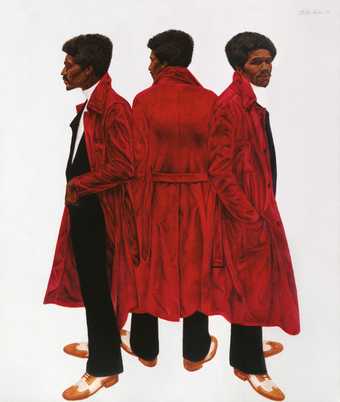

Fig.4

Barkley L. Hendricks

Sir Charles, Alias Willie Harris 1972

Oil on canvas

2137 x 1829 mm

National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

© Estate of Barkley L. Hendricks. Courtesy of the artist’s estate and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York

Fig.5

Anthony van Dyck

Charles I in Three Positions 1635–6

Oil on canvas

844 x 994 mm

Royal Collection, London

© Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II

During his time at Yale Hendricks painted several fellow students, friends and ‘local characters’, including a small-time drug dealer whose self-invention he evokes in Sir Charles, Alias Willie Harris 1972 (fig.4). Hendricks has described the evolution of this painting: ‘When I was in London, I went to the National Gallery, and there was a painting there by [Anthony] van Dyck. And there was a cardinal with his beautiful bed robe on… subsequently, years later, I did a painting that’s now at the National Gallery [of Art, Washington, D.C.] where there were three views of a man with a long red coat: Sir Charles, Alias Willie Harris.’36 While the tripartite view of Harris suggests affinities with van Dyck’s Charles I in Three Positions 1635–6 (fig.5), Hendricks’s portrait riffs on the provocative personality of Charles the drug dealer, who as a ‘procurer of drugs for Yale University students would frequently disappear with their money, like the infamous character “Willie Harris” in Lorraine Hansberry’s award-winning play, A Raisin in the Sun [1959]’.37 Moreover, as Powell outlines, the inclusion of the red coat was not so much a stylistic imitation of what he had seen earlier, but an innovation on Hendricks’s part as ‘a response to middle-class African American prohibitions against wearing the color red’.38

As with George Jules Taylor, in Sir Charles Hendricks describes the formal attributes of dress – silhouette, flounce, line and colour – to evoke the psychological intensity of costume as a reflection of one’s creative psyche. Here, too, we see his facility with colour, not just as a component of composition but as an illusionistic device. In Sir Charles colour is used dramatically to evoke the materiality of cloth, heightening its texture and creating a voluminous effect that activates the painting’s spatial depth, despite its monochrome, flattened background. Along with the figure in triplicate, this illusionism gives a sense of interiority – of psychological depth – while evoking the three-dimensionality of a stage.

The theatricality of Sir Charles, Alias Willie Harris is echoed in Family Jules, although in a slightly different way. Here pattern and texture – of silk, porcelain and wool – accentuate the flat surface of the canvas, rather than evoking the feeling of depth. These accessories, in portraiture, generally act as ciphers, symbolising aspects of individual identity and the ways identity is itself a construction. Hendricks draws attention to the painterly effects of colour and tone in the creation of his accessories to highlight their illusionistic quality and foreground the staged nature of this scene: although unclothed, Jules’s persona is no less constructed.

Fig.6

Anthony van Dyck

King Charles I in His Robes of State 1636

Oil on canvas

2480 x 1536 mm

Royal Collection, London

© Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II

Van Dyck’s portraiture provides a useful starting point for working through these references in Family Jules. In the seventeenth century, court portraiture made material the status of its subjects by deploying the terms of visual engagement as a means of political and social control. Hendricks’s preference for representing the entire body in his portraits drew on the power plays depicted by artists like van Dyck in his monumental portraits of royalty. The King’s pose in van Dyck’s King Charles I in His Robes of State 1636 (fig.6) – hand on hip, elbow resting against a balcony – conveys his regal mastery and stature, both of which are embellished by his robe and crown. Although devoid of the accessories of royalty, in Family Jules the sitter’s mannered gestures – head tilted back, right arm raised – and his position at the apex of the composition likewise require us to look up towards him while he looks down at us. The contrasts in light and dark further consolidate his position on the white settee, giving him the effect of an armature that keeps him closed and distant from the viewer, in a manner that accentuates his self-composure and dignity without lessening his physical presence.

The grand manner portrait, which came into prominence in the eighteenth century following the work of artists like van Dyck, was itself a form of art historical quotation that drew on classical allusions and the techniques of the old masters to meld elements of history painting and portraiture. For its most important proponent, Sir Joshua Reynolds, this idealised, classical approach raised the status of portraiture to a genre that could have lasting significance.39 It also created the effect of continuity between the subject of an eighteenth-century portrait and his or her classical antecedents.40 Audiences were expected to understand these ‘quotations’ as they viewed aesthetically familiar scenes. Already ripe with symbolic significance, then, the incorporation of these historical allusions helped to confer iconicity on the sitter.41 Grand manner portraits drew on these historical lineages as a form of legitimation and elevation on multiple levels: such works displayed an artist’s technical skill, reinforced the validity of portraiture within the hierarchies of painting and emphasised the moral and political significance of the sitters. While generally commissioned by aristocratic and royal figures, this genre of portraiture was also important in depictions of a growing middle and upper-middle class. In their less dramatic, but no less theatrical, individual and group portraits, middle class sitters claimed their right to self-representation by drawing on classicising conventions and symbols to communicate their aspirations and consolidate their social standing.42

It is important to tread carefully here: I emphasise Hendricks’s aesthetics of quotation because he himself makes these references part of the viewer’s experience. But this does not signal an interpretation that seeks to legitimise his work because of this relationship to art historical lineages. Hendricks’s observation that ‘if you could have a Rembrandt or Caravaggio on the wall’, then perhaps ‘you can have [a] Hendricks’ reveals his deep understanding of art history’s complicated genealogy when it comes to the depiction of black subjects and the inclusion of black artists. Aware that portraiture has often been read as a form of visible proof – revealing and legitimising simultaneously the humanity of its maker and subject – his claims, and the claims of Family Jules, run in another direction.

Fig.7

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres

La Grande Odalisque 1814

Musée du Louvre, Paris

Fig.8

Henri Matisse

Blue Nude (Memory of Biskra) 1907

Baltimore Museum of Art, Baltimore

© 2010 Succession H. Matisse/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

We see this particularly in the way that Hendricks successfully melds the conventions of two artistic genres: the portrait and the nude. Hendricks’s positioning of Jules in this instance also recalls another genealogy of representation that is most often associated with the female nude: the odalisque. Jules’s position and Hendricks’s glossy surface certainly recall the lush recline of Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres’s La Grande Odalisque 1814 (fig.7), while the vivid colour and textured surface of Family Jules might recall the fauvism of Henri Matisse’s Blue Nude (Memory of Biskra) 1907 (fig.8). This is heightened by the incorporation of orientalising accessories, in particular the Moroccan tiles whose patterns were copied from examples Hendricks saw during his short visit to Morocco. While these allusions to the odalisque in Family Jules need to be pointed out, as they are clearly legible within the painting from an art historical point of view, we should be careful in how we read them. Making these connections is not an attempt to legitimise the innovation of Hendricks’s work. I am fully aware that moves to include non-white artists within the art historical canon has at times resulted in their inclusion and perceived importance as artists being read through their ability to reference the (European) artists that came before them, such that their significance is always viewed comparatively.43 Hendricks was also aware of this tendency and, as we have seen in an earlier part of this essay, his interest in art historical referents was not a matter of imitation but a way of mastering important technical lessons in painting.

By highlighting the stylistic similarities in Family Jules as compared to these canonical nudes, I want to draw attention to the uniqueness of this painting. Hendricks has taken on a subject – the male nude – that while fairly unusual in the history of art was also historically represented in ways that emphasise ideals of both (white) classical beauty and technical mastery, as seen, for example, in paintings like the English artist William Etty’s The Wrestlers 1840 (York Art Gallery, York).44 Scholars have now begun exploring how black men, in both the United States and Britain, were used as life models (although they often remain unnamed and unacknowledged). These models were usually represented, however, through the idealised physique of Greek sculpture, creating an erotic tension between blackness and physicality.45 Hendricks’s decision to represent Jules in a way that recalls, and deviates from, iconic representations of female availability and depictions of masculinity is on the one hand down to composition: as he explained, he wanted to find the best way to emphasise Jules’s physicality.46 But on the other hand, this explanation also returns us to his interest in the pleasures of self-display. Hendricks’s revision of the male nude in Family Jules can also be read as a response to the erotics of display and desire that shaped aspects of black masculinity in the 1960s and 1970s.47 In a sense, therefore, his deployment of the nude in this painting reinforces the theatricality that instead underpins its function as a portrait.

‘Repetition with a difference’

While eighteenth-century grand manner portraits conferred significance on their subjects through their classical allusions, in Hendricks’s portraits it is the process of creating an association, rather than the association itself, that is central. He has explained: ‘someone once said, oh, he’s doing images that were part of the royalty treatment. Kings and queens were painted the way that I’m painting people now. But … I’m not trying to sort of … put someone in Napoleon’s place, and do a painting of them. No. That’s been done. I want people to be themselves.’48 Allow us to return to Hendricks’s experience at the National Gallery in London, mentioned earlier in the context of Sir Charles, Alias Willie Harris. Noticing the many students making copies of museum artworks, the artist asked the museum director if he could also make sketches in the galleries:

I showed him my credentials from the Academy of Fine Arts, which said that I had won the highest award from the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, and would they extend to me the courtesy of [my] request. And he took my letter and told me to come back the next day. And when I came back the next day he gave me the OK. I went out to buy my supplies and really something hit me like a bolt of lightning. Boom! It startled me. And, it said in essence, ‘You can’t copy someone else’s work’. And that was a revelation thereafter about dealing with your own voice. Even though you can learn from other folks. So that’s what I did … that experience, as I said, was very real, and I haven’t tried to … copy anyone. I’ve looked at hundreds of thousands of images … to see what I could learn and put my own voice to it, and later on in terms of art history and extending that genre of painting to something that [interests] me.49

By foregrounding this notion of referentiality I want to suggest that we understand Family Jules as an artwork whose meaning, in the Derridean sense, always runs in excess of the terms of its signifiers. His aesthetic of quotation is a repetition with a difference, one that always exceeds the referents it recalls.50

The artist and critic Robert Storr has called this process a ‘sampling and recycling … of Eurocentric art history … in order to formulate a new postcolonial approach to narrative art. Art that tells stories that could not have been told by old-fashioned genre and historical painters … because the deliberately and differently orchestrated and accented ironies of this purposeful remix is what the work is all about.’51 While Storr uses this description in relation to the work of contemporary artists including Kerry James Marshall and Kara Walker, a much earlier precedent emerged in Barkley Hendricks’s aesthetic of the quotation in his work in the 1970s. His ‘remixing’ recalls art historical referents not necessarily to rehash their symbolic or social narratives but to construct a visual semiotics that could best reflect the ‘style narratives’ of his time.52 His quotations find their inspiration both in the painterly techniques of his predecessors and the stylistic approaches of his subjects, whose self-constructions were themselves a process of assemblage. Hendricks’s aesthetic is an art historical form of experimentation that foregrounds the personal – the self – as a point of reference. If we need any more evidence of the success of this experimentation, we find it in Family Jules, which works as both a portrait and a nude. There is therefore a correlation between the extraordinary individuality of Hendricks’s subjects and his own artistic ability: each directs the other, so to speak. In an era of competing aesthetic styles, political standpoints and values on race, Hendricks’s psychological exploration of classical forms of realism foregrounded the individuality of black subjectivity itself – both his and his sitters’ – as a site of innovation.