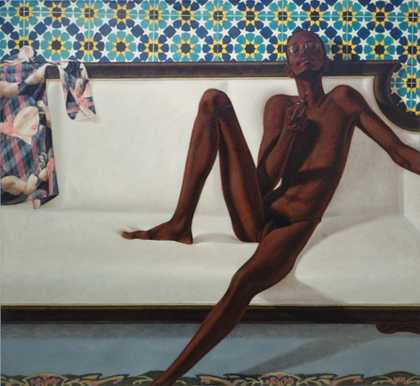

Fig.1

Barkley L. Hendricks

Family Jules: NNN (No Naked Niggahs) 1974

Oil paint on linen

Support: 1681 x 1832 x 35 mm

Tate L02979

© Estate of Barkley L. Hendricks. Courtesy of the artist’s estate and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York

In Family Jules: NNN (No Naked Niggahs) (Tate L02979; fig.1) Barkley L. Hendricks draws on his aesthetic of assemblage to recreate the space of the studio into a space of performance; an ornamented site of private desire. It is almost as if he does this to compensate for his sitter Jules’s nudity, as well as to enhance the theatricality of the scene. While a state of undress might suggest a kind of authenticity, here Jules’s nudity becomes part of the painting’s surface aesthetics. Intersecting bands of colour and pattern both diffuse and absorb our gaze, mediating our relationship with Jules himself. Our eyes move across the surface of his skin, but we never quite rest on one particular site. This play on surface is heightened in the interplay of light and shadow over Jules’s burnished body, as our gaze is continually disrupted by the way his form seems to absorb the light and melt into and out of the shadow. The use of light and shade on the one hand acts as a kind of protective armature, as if to shield Jules from our gaze. Simultaneously, this careful modelling, which heightens the sheen of his gleaming skin, seems also to reinforce the theatricality of Jules’s nudity, the way he ‘wears’ his nudity as an element of his self-construction; another aspect of his charismatic persona.

While Hendricks does partly disassemble the homoeroticism of this painting – a painting of a confident gay black man, made by a confident straight black man – through his evocation of traditional portraiture in Family Jules, the work remains a painting of a desired, and desiring, subject. Jules may recall canonical forms of the female nude – such as Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres’s La Grande Odalisque 1814 (Musée du Louvre, Paris) or Henri Matisse’s Blue Nude (Memory of Biskra) 1907 (Baltimore Museum of Art, Baltimore) – yet these references cannot fully articulate the powerful eroticism projected here through the sitter’s confident self-display and the pleasure that this display brings him.1 Highlighting this here allows Family Jules to deviate from the passive sexuality and objectification that is often associated with the female nude and the figure of the odalisque. Nevertheless, we might find some similarity in the way the eroticism of these paintings is heightened by an attention to surface that in Family Jules is developed via the orientalising motifs he incorporates through pattern and decoration. These patterned surfaces effectively enhance our own awareness of the pleasures involved in looking, incorporating us within the interplay of sexuality and desire encoded here.

Revising the nude

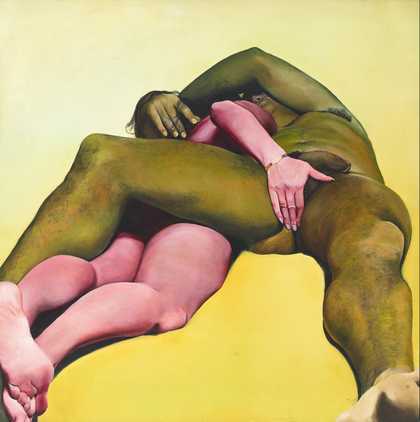

Fig.2

Joan Semmel

Erotic Yellow 1973

© 2017 Joan Semmel/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Photo: Alexander Gray Associates, New York

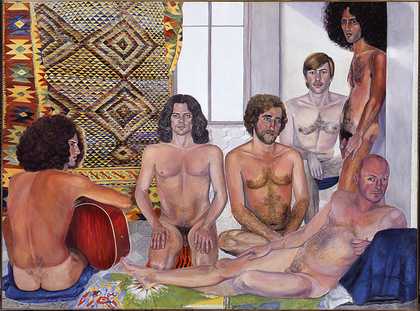

Fig.3

Sylvia Sleigh

The Turkish Bath 1973

Smart Museum of Art, University of Chicago, Chicago

© Estate of Sylvia S. Alloway

Given the rarity of depictions of the male, rather than the female, nude in art history, it is important to mention that other revisions of the male nude were being undertaken during this period. Here we might think of Joan Semmel, whose ‘sex paintings’ and ‘erotic series’ from the early 1970s reclaimed the female gaze in her explorations of sexuality depicted in the expressionistic figuration of male and female nudes (see, for instance, her Erotic Yellow 1973; fig.2). Sylvia Sleigh is another significant artist who, like Hendricks, was invested in realism. Using portraiture and landscapes she explored values attached to representations of women and men, and was particularly interested in the absence of eroticised imagery of men in Western art. In several of her paintings she addressed this by inserting the male nude into situations that referenced the well-known feminising and orientalising tropes of artists like Ingres and nineteenth-century painter Édouard Manet. In this sense, her 1973 painting The Turkish Bath (fig.3) resonates in interesting ways with Family Jules. A direct reference to Ingres’s painting of the same name, Sleigh depicts a group of nude male art critics – including her husband, Lawrence Alloway – reclining and sitting in a well-lit room that is decorated with rugs and wall hangings that seem to incorporate both Orientalist and Native American motifs. Each body is carefully detailed as Sleigh intimately recasts the male nude through the female gaze, emphasising the figures’ beauty and their erotic power. Interestingly, the North African motifs seen here were also increasingly being used to decorate New York bathhouses that were becoming a newly fashionable space for men, both gay and straight, to spend time during the 1970s. These patterns were incorporated into murals, into fantasy environments that recreated erotic situations, or were simply installed as decorative elements.2 As historian George Chauncey has observed, these bathhouses, while attracting men for the sexual possibilities they offered, were also important sites for the development of social ties, and a safe place to express, perform and take pleasure in one’s sexuality.3

Reading Family Jules through this added layer of signification on the one hand reinforces the (homo)eroticism of the playful, even fantasy-like staging that is carried out here: it is almost as if the studio has become another erotic space. This playful eroticism is repeated in the first part of the title: ‘Family Jules’ is a pun on the euphemistic description of male genitalia as ‘the family jewels’. Sexuality and desire are always embedded in discourses of the nude, but it is important to consider here the meaning of these dynamics with respect to the production of Family Jules. In the context of the racial relations and the political climate of 1970s America, positioning a nude, gay, black man as the site of desire would have been a confrontational act: an effect enhanced by the fact that the painting was made by another black man, though this time straight. What is interesting to consider here is how the eroticism at play in this painting can allow for a deeper exploration of the intersection of race, masculinity and sexuality in the 1970s.

Desire and masculinity

The nude in art history is generally understood to be a site of projection: a body on which viewers could see their own desires and fantasies reflected back. The eroticism encoded in Family Jules, both in terms of Jules’s nude body and the textured surface that frames it, obstructs our ability to visually ground our relationship to the picture through the body on display. Hendricks effectively prevents the viewer from ‘projecting’ onto Jules. Instead our view is reflected by Jules himself, who looks down at us through his glasses. Rather than projection, which is a relationship based on the contrast between what is depicted and what is seen, what is mediated here is the relationship between viewer and subject, as shaped by the medium of reflection.

Hendricks’s attention to surface draws viewers close. As we scan the canvas, our position is metaphorically reflected back to us on the surface of Jules’s glinting glasses: we can imagine seeing ourselves looking. By positioning Jules on the other side of this mirror as our reflection, so to speak, Hendricks heightens this process of seeing and being seen. Not only are we made aware of our viewing position as our gaze is reflected back to us, but we are also compelled to consider the visual process of recognition itself. This is reinforced in the dynamics of looking that takes place within the painting. The face of the white woman that is printed onto the shirt resting on the left side of the sofa looks towards Jules, her disembodied pink lips pursed and glossy and positioned at the top of the sofa, in direct alignment with the line of Jules’s mouth. On the one hand, the shirt balances the composition by filling in the blank whiteness of the sofa and deepening the three-dimensionality of the space through its contrasting effect with the pattern above and Jules’s gleaming form. On the other, however conscious or unconscious this evocation of interracial desire, it might also be read in the context of the 1970s as a reminder of the violent outcomes associated with such relationships – then only recently legalised after the overturning of Anti-Miscegenation Laws following the Loving v. Virginia case of 1967.4 Furthermore, it may also be a sly reference to Hendricks’s own personal relationships with white women. But this seemingly decorative element could also be a device through which to reflect on the conventional constructions of representation that surrounded the black male body in the 1970s.

The latter part of the work’s title, NNN (No Naked Niggahs), while recalling the signage of segregation and those other letters in triplicate, the designation ‘KKK’, alludes to the threatening spectre of black masculinity as it was constructed in the 1970s and still is today. Through media and print outlets the hyper-sexualised or criminalised black male body remained a continual subject in popular culture, and Jules’s nudity heightens the construction of black masculinity understood as a physical threat. This historical moment did, however, figure a new kind of visibility for the black male body, a reappraisal that revolved around new kinds of self-presentation that signified racial alterity, confidence and self-possession.5 Debates about black masculinity – bringing together concerns about race and sexuality – were sites of tension among black American communities, and also reflected larger questions about black equality, inclusion and autonomy. As the civil rights era of the 1950s and 1960s gave rise to the pluralism and social revolutions of the 1970s, renewed attention was paid to forms of black radicalism. The Black Power Movement emerged as a challenge to what many leaders in the black community felt were the conciliatory attitudes of organisations such as the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, seen as being mostly beneficial for an integrationist black middle class.6 Leaders of the Black Power Movement and groups like the Black Panthers, in opposing what they perceived to be the integrationist rhetoric of an earlier civil rights generation and the expectations of white America, often embodied and displayed ‘an aggressively heterosexual masculine persona as a way of waging psychological warfare against their white male oppressors’, as sociologist Michael Messner notes.7 As curator Thelma Golden argues, these individuals created ‘codifiable images of black masculinity – big afros, black leather jackets, dark sunglasses and guns’, amplifying popular constructions and stereotypes of the idea of ‘black macho’ to reanimate and recoup them as radical signs of blackness and autonomy.8 As feminist scholars have shown, in responding to the racist and economic abuses of white supremacy these discourses of black liberation ‘equated black freedom with a reassertion of black patriarchy’, as Kimberley Springer describes it.9 This involved maintaining black women in subordinate roles, despite the centrality of black women activists to these movements and their challenges to common conceptions of gender, identity and freedom. They emphasised the intersection of black liberation and gender equality struggles, called for women to have the right to full social, political and economic equality, and promoted agendas that addressed issues specifically related to black women’s experiences including poverty, employment, housing and birth control.10

In their assertion of control and power, these constructions of black masculinity connected (male) sexual freedom to forms of social freedom. There was a political consciousness to these stylings of black masculinity that sought to critique white patriarchal masculinity, even as it challenged the middle-class ideals of respectability and integration of an earlier generation. In a sense these debates over masculinity, race and sexuality were also debates about the revolutionary possibilities of style and aesthetics and their ability to usher in the new social parameters needed for black liberation. These debates were enacted in visual form through the rise of ‘blaxploitation’ films that celebrated the complexity of urban black life (often in opposition to black bourgeois culture). Such films, two of the most famous being Melvin van Peebles’s Sweet Sweetback’s Baadassssss Song (hereafter Sweetback) and Gordon Parks’s Shaft (both released in 1971), gave rise to a suite of mythic black male and female characters who, although often hyper-sexualised and violent, also expressed what writer and musician Greg Tate has called the ‘cultural confidence’ of the 1970s.11 Blaxploitation cinema continually returns us to the signifying power of the black male body in order to establish his dominance over white men: whiteness is aligned with femininity and therefore with weakness. But the economic vulnerability of black men is also highlighted in these films, as a barrier to their social dominance.12 Sexuality in these films, often couched as a form of liberation, is therefore complicated: in one scene from Sweetback, for example, the main character’s freedom from oppression (a white policeman) is obtained by raping a white woman, creating a connection between his literal freedom and the sexual freedom that was emphasised by some in the Black Power Movement.13

This connection between sexuality, violence and masculinity reveals the complexity of debates around gender and race and the struggles for black equality that they often accompanied. While immensely popular, Sweetback, which was described by its director as the story of a ‘bad nigger who challenges the oppressive white system and wins’,14 was nevertheless met with resistance by both white and black media outlets for its negative portrayals of black urban life and the ‘sexploitation’ of its main character. Two reviews of the film help to explain these contrasting attitudes as they played out in the black community, particularly along class fissures. Writing in Ebony in 1971, the critic Lerone Bennett roundly criticised Sweetback for romanticising the poverty and misery of urban black life and for basing its characters on stereotyped characterisations of the black urban hustler and his opposite, the black bourgeois ideal of the ‘upright Negro’.15 Both failed, according to Bennett, to adequately explain the black experience or to express a defined black aesthetic, revolutionary or not, and instead reinforced white supremacist constructions of blackness. Bennett’s article was as much a take-down of the film as it was a critique of critic Huey Newton’s response to Sweetback in which he argued for the film’s importance for its representation of community solidarity, its demonstration of the need for unity between black men and women, and its depiction of black victory and survival.16 In response to Newton’s argument that this is ‘the first black revolutionary film’,17 Bennett observes: ‘nobody ever fucked his way to freedom’.18 This exchange highlights the class tensions and ideological conflicts and controversies surrounding black aesthetics and its relationship to the freedom struggle, and how these also crystallised in the broader debates about masculinity, sexuality and race during this period.

The politics of respectability

Hendricks’s deployment of the nude in Family Jules and its knowing wordplay needs to also be situated in relation to some of these tensions around sexuality and the constructions of gender as they played out in both white and black communities. Hendricks was well aware that for both white and black audiences – including some of his own family members – Jules’s nudity was too confrontational and was perhaps the reason that the painting was only put on view a small number of times between its production in 1974 and its acquisition by Tate in 2015.19 Hendricks understood the respectability politics shaping black responses to nudity as a form of conservatism that inevitably reinforced the stereotypes around race, gender and sexuality circulating in mainstream culture.20 He explained it in this way: ‘Black people are fucked up too, on a number of levels. They can’t help it, given the way this society, this culture, has squeezed their heads.’21 But he was also aware of the hypocrisy of proscriptions around black nudity. He recalled being in negotiations for a solo exhibition at the Birmingham Museum of Art in Alabama, which refused to show any of his nude paintings, including self-portraits. ‘No … nudes period. So, that pissed me off. And I said no, no show at all. The letter I wrote to them said, look, you didn’t have any problem showing any black naked slaves.’22 It is this imbalance that Hendricks addresses by foregrounding the individuality of his subjects, showing them on their own terms to evoke the ‘pleasantry-style beauty, genius, skill, that’s a part of what we’ve brought to America and the world that doesn’t get addressed the way that I feel it could’.23

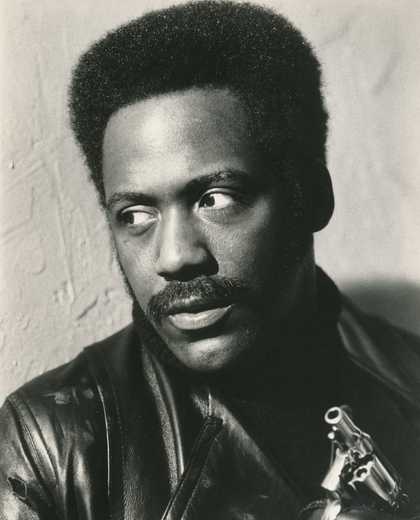

Fig.4

Richard Roundtree as private detective John Shaft in Shaft (1971) (film still)

Jules’s depiction in this painting – his self-confident posture and self-possession, the ownership of his body that he displays – might be said to evoke the affectations of sexualised 1970s icons such as Huey Newton, or the characters of Sweetback and Shaft (see the film still of Richard Roundtree as Shaft; fig.4). But their bristling, heterosexual physicality is here playfully disassembled, perhaps even queered, in Jules’s powerful projection of autonomy and sexuality.24 In Jules’s earlier portraits Hendricks evokes what Powell calls the ‘player chic aesthetic’ with its emphasis on ‘fanciful, frequently counter-cultural and pret-a-porter clothing’25 that gave rise to a 1970s version of the character of the dandy: a cool, debonair figure whose sartorial style reveals black men’s self-authored visibility and protective forms of self-expression during economic and social upheaval. This same attitude continues in Family Jules, amplified here in the sitter’s confident enjoyment of the viewer’s gaze. In deploying the genre of the nude to capture Jules’s unique physicality Hendricks ultimately transforms it into a vehicle for individual self-expression that returns us to the careful construction of the self as itself a form of pleasure. Jules’s posture also evokes the elegant self-possession of black male fashion models of the time such as Sterling St Jacques, who were reaching new heights of visibility on magazine covers, walking down fashion runways and appearing in the tabloids. Jules’s self-display, and Hendricks’s paintings of this period more generally, overlap with a new visibility afforded to black men in the 1960s and 1970s, evident in the proliferating number of images of the black male body across multiple mediums and outlets that functioned as modes of self-expression and as fetishised signs of racial difference. The eroticism at play in Family Jules powerfully accentuates the visual pleasure of these forms of sartorial expression that emphasised the allure and attractiveness of black masculinity. Importantly, however, the pleasure of being on display, the desire to be recognised and the desire that goes with recognition as shown in Family Jules revolves around a homosocial connection. It is one built on mutual respect and trust, rather than a shared sexual identity, designed to imagine and present a more ambiguous, multifaceted expression of black masculinity that is also a departure from what feminist writer bell hooks has called the ‘phallocentric black masculinity’ of the period.26

Visual pleasure, humour and the black male body

Family Jules subtly critiques, or rather destabilises, the dominant constructions of militant masculinity circulating during this period, even as it challenges bourgeois ideals of respectability. Both inevitably revolved around a politics of authenticity, anchoring blackness to forms of embodied expression. In Family Jules we see a defiant performance of masculinity that is no less radical for its time in its expression of a black male sexuality that is both individualised and autonomous and that acknowledges, without fetishising, the multiple modes of visual pleasure attached to the black male body. Deploying the circuits of desire embedded in acts of display and representation, the painting enacts a form of mutual recognition that queers the politics of identity that reinforced heteronormative expressions of sexuality and patriarchal identity.27

In Family Jules the self-conscious quotation of traditional nude and portrait paintings and the painting’s focus on the construction of surface works with these frames of reference, questioning the ways in which categorical strategies of representation and identification overdetermine representations and readings of the black body and the African American artist. Family Jules sees Hendricks vividly exploring the possibilities of self-expression while also exposing these limiting conditions. This process is underlined by the humorous pun of the title, whose two coordinates – before and after the colon – both raise and deflect these conditions in particular through the word ‘niggah’. Hendricks explains:

I do have some reservations about … following a particular unfortunate area of description that we have. But let’s face it. You know, there’s a whole area of descriptions that are used in terms of us that I can’t change. I don’t want to sort of encourage it further. But my use of it, there’s a humour element. Yeah, I mean you hear it all the time, you know. And, as I say, some of it is funny as hell, you know. And I don’t ever sort of downplay our humour. And I’ve heard the word used [in ways] that have caused certain people consternation. And certainly within the context of the black community, it’s a constant area of consternation.28

Confronting this ‘area of consternation’, Hendricks uses the word ‘niggah’ to refer to its private and public meanings. On the one hand it references an earlier painting of his entitled New Orleans Niggah 1973 (National Afro-American Museum and Cultural Center, Wilberforce), which was a nickname that Jules used for himself, thereby recalling the comfort and closeness of their relationship and the way that the word was used, according to curator Floyd R. Thomas Jr, ‘as a term of endearment or an expression of style’ within the black community.29 As art historian Erica Moiah James has pointed out, the word ‘niggah’ was deployed differently, and understood differently, from the historical word ‘nigger’ during the 1970s, not ‘by middle class blacks but certainly by working-class blacks in places like North Philly … it was constantly being reinvented and used colloquially’.30 This reuse of the word ‘niggah’ suggests that the word ‘oscillates’ in different spaces.31 We might also think here of Richard Pryor (1940–2005), another black linguist whose stand-up comedy routines frequently revolved around the word ‘nigger’. As cultural historian Glenda Carpio has explained, Pryor used the term to recall its public history of slavery, violence and segregation, but by ‘culling humor out of racial violence Pryor asserts what Freud called the triumph of narcissism … to signify the victory of the ego which refuses to be hurt by the arrows of adversity and instead attempts to become impervious to the wounds dealt it by the outside world’.32 The full title of Family Jules, when read in its context as a quip made by a friend about black nudity,33 seems to align with Pryor’s semantic doubling. This signifying practice foregrounds black empowerment without subsuming the vulnerability of black life, calling attention to the surface of the black body while also creating a structure for its protection.

In Family Jules, then, the word ‘niggah’, in referencing this history of racial violence, also deflects its power through the self-reflexive humour it channels, amplifying the assertion of style and self-possession that Jules embodies. The humour of the title extends into the painting itself by Hendricks’s aesthetic of quotation, and the knowing references to art historical and cultural signifiers that are never quite realised. These sly deflections are reinforced in the shifting terms of Jules’s nudity, which remains somehow elusive amid the shadows. We are drawn to the surface of his body, but never quite able to fully grasp hold of it. As art historian Krista Thompson cogently points out, ‘artists who draw on surfacism and its connection to black bodies implicitly call up a connection between surface aesthetics, capitalism and the denial of subjectivity to enslaved persons of African descent’.34 Within this history, black skin – naked, greased and oiled to make it shine – helped to increase the value of enslaved bodies and ‘sealed them … in crushing objecthood’.35 Hendricks’s decision to paint Jules naked certainly works to dismantle this ‘crushing objecthood’ – a term Thompson draws from psychoanalyst and philosopher Frantz Fanon36 – but not simply by offering a corrective to these histories. His foregrounding of the surface of Jules’s body becomes a process of the deferral – or deflection – of meaning as a gesture that expands the categories and conventions framing how black bodies could be understood during this era, and are still understood today. This process, in other words, returns us to the individuality of Jules’s self-styling, the terms of which challenge both black and white audiences’ perceptions.

Moving between the various calls and categorisations of twentieth-century American art, Family Jules is a powerful exemplar of Hendricks’s oeuvre. While Jules’s body might remain elusive, the painting itself creates a connection between the viewer and the object through what Hendricks has called its ‘human scale’. He explains:

There’s an aspect of illusion that’s facilitated by keeping my images close to life-size. I keep it pretty close to the human scale [so] it has that area of illusion that pulls you in. If you get too large, it’s like a billboard, and if you get too small, it’s like one of those miniature things. It’s that interaction with the spectators that helps facilitate certain areas of illusion.37

This emphasis on interaction and scale returns us to the question of recognition. Family Jules is a painting that stages a close interaction between the viewer and the artwork, compelling us to engage with its subject. We are, as Hendricks puts it, ‘pulled in’. This staged encounter, correlated through size, allows a spatial connection to emerge between viewer and subject that reinforces an equivalence between the onlooker and Jules himself. Using the size and positioning of the canvas to amplify our relationship to the subject heightens our physical proximity to Jules, compelling us to see him as we would in life. This physical correlation between viewer and subject is an important factor in all of Hendricks’s works, and this correlation is the corrective that Hendricks offers: ‘I use white and black only because it’s a way of facilitating ease of being understand [sic]. They’re not white, we’re not black. I’m a colourist, you see. I use that as a way of being understood, because … you’ve gotten screwed with certain areas of terminology.’38 It is this terminology or dialogue, filtered into descriptors like ‘black’ and ‘white’, that a work like Family Jules addresses. While Hendricks’s use of colour provides the support that grounds Jules, as well as protecting him, it also becomes the means through which the artist plays with and deflects our frames of reference. This deflection is offset by the spatial dynamics of the painting that allow us to approach the subject on something like an equal footing from a position that mediates, perhaps, a physical connection. In the final instance, then, Hendricks returns to the question of recognition, and our role in the process, conflating the pleasures of being looked at and the pleasures of looking in order to challenge the very conditions by which viewers understand – and see – the meanings of race, gender and identity in the visual field.