It hardly needs to be said that Barkley L. Hendricks’s portrait paintings have a timeless quality, perhaps owing to his meticulous attention to detail. Whether his subjects were painted in the 1960s, the 1970s or in 2017, there is a specificity to them that makes them instantly recognisable as individuals and as iconic figures from a particular era. But there is more to Hendricks’s portraiture than legibility. A work like Family Jules: NNN (No Naked Niggahs) 1974 (Tate L02979) powerfully reveals his sensitivity to self-creation and self-performance as a form of aesthetics and his ability to translate these expressions without lessening, but rather amplifying, their corporeal presence in the world. Furthermore, in a society in which the proliferation of both social and mass mediated imagery has made (self-)portraiture almost ubiquitous, Hendricks’s preoccupation with spectatorship, theatricality and exhibitionism make his work appear both ahead of its time and immediately contemporary.

The contemporary black body

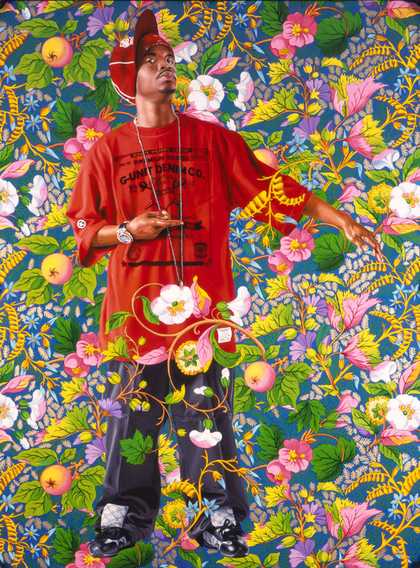

As art historian Richard J. Powell observes, Hendricks’s ‘forays into questions of race, gender and self-invention are pivotal (if not canonical) to figurative realism in modern painting’.1 While his work may be considered political insofar as it expands the breadth of the art historical canon, its aesthetic motivations are clearly different from those of contemporary artists like Kehinde Wiley or Titus Kaphar. Yet both of these artists’ depictions of the black body, and Wiley’s interest in fashion, evoke certain similarities with Hendricks’s detailed realism. Their facility with colour and the materiality of paint, and their explorations of the tonalities of skin, along with the referential way in which they draw on historical modes of painting, reveal further art historical links with Hendricks.

Fig.1

Kehinde Wiley

Portrait of a Venetian Ambassador, Aged 59, II 2006

Collection of Jeanne and Dan Fauci

© Kehinde Wiley

In Wiley’s baroque renderings of his young black and brown subjects, as well as in the densely packed surfaces of paintings by British artist Chris Ofili (such as Afrodizzia (2nd version) 1996 and Blossom 1997, both Victoria Miro Gallery, London), we also see a contemporary updating of Hendricks’s attention to surface in their juxtapositions of the figure with intensely patterned grounds. This is evident, for instance, in Wiley’s Portrait of a Venetian Ambassador, Aged 59, II 2006 (fig.1), where a young man dressed in distinctive hip hop fashion emerges from a gorgeous patterned surface of lush fruit and flowers. His pose melds aristocratic dignity with the bravado of a break dancer’s freeze, creating a striking contrast between the race, class and age of the subject and that of the sitter in the original portrait by an unknown artist, Portrait of a Venetian Ambassador, Age 59 c.1592–1605 (Columbus Museum of Art, Columbus). The contrast is heightened by Wiley’s clear references to more contemporary forms of self-imaging and performance, such as the hyperbole of music videos.

There are, of course, obvious differences between these artists. Wiley is clear about the gaps in the canon that he is addressing and his monumentalised images recoup the black (usually male) body as an idealised figure of art historical significance.2 The viewer is orientated towards Wiley’s subjects, then, as if they were the historical subjects whose poses they emulate. Wiley in particular uses this effect – as art historian Krista Thompson has shown – to explore the multiple ways that blackness is consumed, marketed and produced. His interest in the intersection of consumerism, fashion and black identity at a time of ‘emblazoned black visibility’ also evokes Hendricks’s mediation of the realms of popular culture and fine art, although from a different perspective.3 But Hendricks’s continued melding of these realms also finds new variations in the portraiture of Luis Gispert, whose large-scale photographic portraits – such as Untitled (Three Asian Cheerleaders) 2001 (Whitney Museum of American Art, New York) – explore what he calls the ‘baroqueness’ of urban hip hop culture.4

Displaying individuality

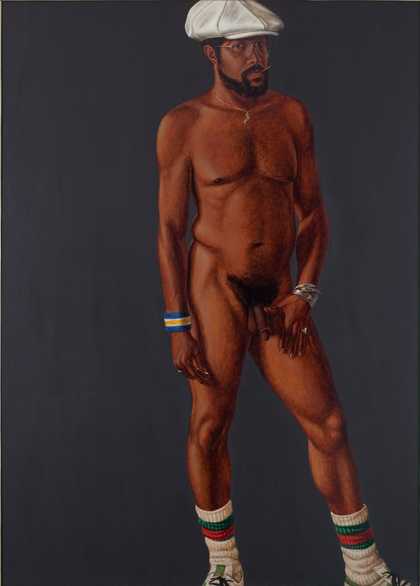

Fig.2

Rashid Johnson

Self-Portrait in Homage to Barkley Hendricks 2005

APT Institute, New York

© Rashid Johnson

Fig.3

Barkley L. Hendricks

Brilliantly Endowed (Self-Portrait) 1977

© Estate of Barkley L. Hendricks. Courtesy of the artist’s estate and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York

Although they are participants in and consumers of a visual economy in which the black body remains both hyper-visible and marginalised, Hendricks’s subjects also reveal themselves to be in possession of the terms of their display. Rashid Johnson’s nude Self-Portrait in Homage to Barkley Hendricks 2005 (fig.2) captures this attitude, both in its reverential quotation of Hendricks’s nude self-portrait Brilliantly Endowed (Self-Portrait) 1977 (fig.3) and in the bold assertion of a black masculinity still reads as threatening in popular culture. This sense of autonomy, and this critique of the limits of figurative realism, also finds its way into the paintings of Kerry James Marshall and is rendered into complex explorations of beauty, desire and sexuality in the female figures of Mickalene Thomas. Thomas’s emphasis on the sensuality of form and her remixing of the art historical precedents of landscape, still life and the nude in works like A Little Taste Outside of Love 2007 (Brooklyn Museum, New York) translate, like Hendricks’s work before her, the phrase ‘art for art’s sake’ into an exploration of the self-reflexive strategies and performances of display.

What is perhaps most powerful about Hendricks’s work is the value he places on an aesthetics of individual self-expression as a subject, in and of itself, for fine art. Without downplaying the politics of style, Hendricks foregrounds individual uniqueness as a way of giving voice to something more collective. His paintings are relational in the truest sense of the word: his subjects are active participants in their worlds and ours. While his technical mastery has certainly expanded the terms of figural realism through innovations in texture and colour, composition and size, he does not use his representational style to be representative. As such, while his unrelentingly cool and audaciously hip subjects – epitomised by a figure like George Jules Taylor – have reinvented the terms by which black subjects can be represented artistically, they have also expanded the aesthetic frameworks through which a younger generation of American artists (and scholars) can comprehend and interrogate the interactions of culture, identity and race in the United States.