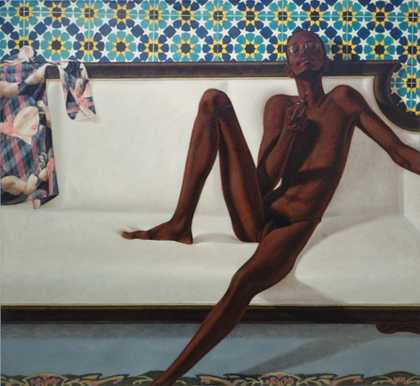

Fig.1

Barkley L. Hendricks

Family Jules: NNN (No Naked Niggahs) 1974

Oil paint on linen

Support: 1681 x 1832 x 35 mm

Tate L02979

© Estate of Barkley L. Hendricks. Courtesy of the artist’s estate and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York

While certainly embodying the spirit of the phrase ‘black is beautiful’, in Barkley L. Hendricks’s Family Jules: NNN (No Naked Niggahs) 1974 (Tate L02979; fig.1) the sitter’s unflinching gaze and his bold nudity offer a challenge to viewers’ perceptions of the intersection of race, gender and sexuality.1 This was a time when popular conceptions of black masculinity ranged from threateningly violent in the white imagination to the differently orientated but connected ideals of middle class propriety and militant masculinity in black communities. With its seductive sheen and unabashed theatricality, Family Jules signals the oscillating meanings of blackness as both an individual and a collective form of identity in the 1970s. To examine this further it is useful to ask: what is the relationship between a black artist and his or her community?

‘The New Black Arts’

This was a question posed by Sherry Turner, a writer for the hard-hitting political and cultural journal Freedomways. One of the foremost African American publications in the two-and-a-half decades between its establishment in 1961 and its closure in 1985, Freedomways brought together the writings of black artists and intellectuals across generations. In a 1969 essay in the journal titled ‘An Overview of the New Black Arts’, Turner noted that these arts were ‘a particular way of giving expression to Black energy; an artistic putting down of what is actively going on in the lives of Black people. It’s asking Black people to dig themselves as they are, to be themselves and to be more. The new Black art seeks to divorce itself from Western art’s “art for art’s sake”.’2 As she pointed out, however, ‘While the young Black poets are almost uniformly committed to producing a functional art directed towards the Black community, one finds many young Black painters do not direct their art specifically toward the Black community and do not feel that they should.’3

Turner’s essay highlights the tensions that resided in black artistic production during this period. Her understanding of what the ‘new Black arts’ were and their evolution in relation to a broader black community resonated with a speech made by the artist Elizabeth Catlett some eight years earlier called ‘The Negro People and American Art at Mid-Century’, in which she argued for an art that ‘would express racial identity, communicate with the black community and participate in struggles for … equality’.4 Catlett’s call for a ‘black aesthetic’ was taken up by a younger generation of artists whose concerns with the experiences and sensibilities of black Americans came to define the black arts movement. Aesthetically the black arts movement encompassed a range of artistic styles and mediums, led to the professional expansion of black art through the opening of museums and black-owned galleries, and was, according to art historian Lisa Farrington, ‘formalized on a global scale through the organization of FESTAC in Dakar, Senegal in 1966 and Lagos, Nigeria in 1977’5 – coincidently, the latter was an event that Hendricks also attended. The imagined homeland of Africa became for many in the black arts movement a source of aesthetic and political inspiration, and an alternative source and methodology for understanding black expression. The question of defining an artist’s relationship to his or her community was therefore not simply a cataloguing of subject matter. Rather, it was part of wider attempts to develop an art historical language – a critical methodology – to historicise and frame the ways ‘black artists were at once part of, and still working in ways different from, Western canonical modes’, as art historian and curator Kellie Jones described it.6

In contrast, as Turner points out, other artists challenged this idea of a specifically ‘black’ aesthetic that separated art made by African Americans from their white counterparts. Raymond Saunders, who had graduated from the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts in 1957, published his historic essay ‘Black is a Color’ in 1967, arguing that ‘race was extraneous to art’. He wrote: ‘Some angry artists are using their art as political tools, instead of vehicles of free expression. An artist who is always harping upon resistance, discrimination, opposition, besides being a drag … unwittingly (and witlessly) reviv[es] slavery in another form. For the artist this is aesthetic atrophy.’7 Saunders launched this critique as the Black Power Movement and the black arts movement made blackness into a powerful sign of identity, and his aim was to challenge viewers to reflect on what blackness means just as a colour rather than as a ‘political consciousness or way of thinking’, as cultural historian Margo Natalie Crawford has noted.8

These debates over black art cannot be decoupled from their social contexts. Following the civil rights movement of the 1960s, the 1970s was a period of tension as these changes were both embraced and rejected.9 The goals of the movement became institutionalised in part through various pieces of legislation and the increased participation of black Americans in institutional and economic spheres. The civil rights movement also inspired other movements among Indian American, Asian American, Latinx and LGBTQI communities, as these groups demanded change and recognition. However, there was also backlash against school desegregation, while the economic crisis of 1970s America meant some parts of the white population were resentful of efforts to create equality through affirmative action. While certain segments of the black population did make greater strides, economically and politically, during this period, the equality aimed for in the civil rights agenda did not come swiftly to many African Americans, and black communities still grappled with momentous racial and political uncertainties.10

Black artists were also positioned in an art world that was slow to accept them into the fold. The late 1960s and the 1970s also saw a groundswell of arts activism by artists of colour and women in particular, who demanded greater access, inclusion and equality from arts institutions including the Whitney Museum of American Art and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, both in New York. Collectives such as the Black Emergency Cultural Coalition, founded in 1969, protested the controversial Harlem on My Mind exhibition held at the Metropolitan Museum that same year, which exhibited representations of Harlem and its communities without including Harlem community members or a single artwork by African American artists. Boycotts of other exhibitions and museums followed, including the 1971 Whitney show Contemporary Black Artists in America. This was one of the first major exhibitions to include Hendricks’s work, along with that of several other black artists including Romare Bearden, Barbara Chase Riboud and Betye Saar. Curated by Robert Doty, it failed to seriously consider professional advice from the black community, such that several artists questioned its legitimacy and withdrew from the show, including Sam Gilliam, Richard Hunt and Roy de Carava. Reviews of the exhibition, and the catalogue itself, tended to focus on black artists in relation to social and political concerns, reaffirming racial polarities already existent in the New York art world at the time.11

Blackness as colour, form and identity

Hendricks’s artistic development during the 1960s and 1970s took place alongside these political and aesthetic debates, although he was never wholly interested in participating in them directly.12 These debates also coincided with the proliferation of post-1960s art forms, from minimalism to process art, from pop to post-painterly abstraction, all of which left the figure behind. A more recent and renewed attention to the discourses around abstraction and representational art of the period reminds us that these artistic ‘divides’ between abstraction and what we consider representational art are less stable and differentiated than has often been assumed.13 These studies are also, importantly, working to challenge overdetermined correlations between representational art and its political significance at the expense of the aesthetics of abstraction. Scholars such as Darby English, for example, have emphasised how abstraction provided artists with a way of moving beyond the ‘confines of black representational space’.14 English is interested in denaturalising blackness as a form of essential identity, and in abstraction he sees how this might take place in a way that figuration might not so readily accomplish. In a sense, English also echoes Raymond Saunders’s critique of the excessively defined nature of blackness, a critique that also runs through Hendricks’s commitment to figuration. Although representational, in Family Jules Hendricks plays with aspects of abstraction that compel us to reflect on the meaning of blackness – as colour, form and identity. Highlighting this dynamic within the painting is not to downplay its realism, but to allude to the ways Hendricks sees figuration as a means of moving beyond and challenging the overdetermined meanings of blackness as they emerged both within and outside the black and artistic communities of which he was a part.

While Hendricks remained interested in the expressions of a diasporic black community, he says his travels to Africa in the 1970s and thereafter ‘helped to point out how American I am … I was talking to an art historian … and I said, we’re Americans of African descent. If we have to sort of deal with any area of description. And it’s not denying our African heritage, and it’s not denying our American heritage. It’s not exalting either one of them’.15 Hendricks’s critique of the ideology of pan-Africanism often associated with the black arts movement and the political aims of the Black Power Movement foregrounds a dialogical understanding of art making that reflects another approach, taking form around black art of this period. Here we can think of artist Frank Bowling’s seminal 1971 essay on black abstraction, ‘It’s Not Enough to Say Black is Beautiful’.16 Bowling’s essay – while concerned with abstraction rather than the figure – is significant for its exploration of the process of signification that brings together the multiple dialogues and experiences of black artists. Foregrounding the encounter between black artists and Western as well as other artistic traditions, and building on the work of Robert Farris Thompson (one of Hendricks’s former professors at the Yale School of Art), Bowling emphasised the diasporic nature of black artistic practice that came together through ‘disguise, double entendre and the ability to repeat with a difference’.17

In Family Jules, this ‘repetition with a difference’ is, to borrow the words of art historian Kobena Mercer, a strategy that interrupts ‘official consensus or orthodoxy by articulating a double-voiced mode of address that is as critical of conservative tendencies in black popular culture as it is pointed in its stance towards mono-cultural tendencies in national and international art worlds’.18 It is also a strategy derived from the vernacular styles of the beginnings of a post-civil rights expression of democratised blackness that was moving beyond the bounds and definitions of the black middle class. This democratisation of blackness brought together the politicisation of style and of art, as the term ‘black’ increasingly suggested new possibilities of self-expression, self-actualisation and self-performance. The broader context for this reading is also the specific politics of the 1970s. We might consider the ways the ‘black is beautiful’ aesthetic of early blaxploitation films ‘rupture[d] the idea that “white is right”’,19 as cultural theorist Jennifer Devere Brody notes, and showed that, in the words of film and music historian Charles Kronengold, the ‘performance of everyday acts of style had political consequences’.20 We might also consider the sartorial expressions of working class disco culture (in films like Saturday Night Fever of 1977) as expressing a similar form of what cultural historian Will Kaufman refers to as ‘self-assertion in the face of limited opportunities for upward mobility’.21 What Family Jules helps us work through, then, is the way the performance of blackness came to be articulated through an attention to the body as a surface, one that ‘carries on and within [it] an invitation to look at, rather than look away’, in the words of literary historian Anne Anlin Cheng.22 The semiotics of surface, style and self-fashioning was given scholarly attention by members of the Birmingham Center for Cultural Studies and in particular in Dick Hebdige’s seminal book Subculture: The Meaning of Style (1979). But before this was Barkley Hendricks who, rather than speaking for a collective identity or using his art as a corrective lens, explored the particularity of his sitters’ experiences and self-construction as they worked through the condition of blackness as one of living in relation to images, circulated in the public sphere.

Between figuration and abstraction

While Hendricks is clear about his commitment to figuration, what makes a work like Family Jules so significant is the way it compels us to see this artistic and political period in new ways, precisely because it straddles the divide between abstraction and figuration. In doing so it brings together these multiple dialogues to challenge overdetermined constructions of blackness and to reflect on it critically as a form of identification. Hendricks explains:

How many black people … were part of any kind of visual information that didn’t deal with what I call the misery of my peeps? You know, you can always find visual information that deals with the hardship, slavery, and all the rest of it. I’m not denying any of this by any stretch of the imagination, but I’m trying to sort of address a situation that’s not a part of that. I’m not about our hardships and I felt that I can’t right the wrongs of America, [although] I will never say that you can’t make a statement about that, and if you choose to – if your head is sort of in this kind of position – it has to affect you in a way … [T]here’s enough of the pleasantry-style beauty, genius, skill, that’s a part of what we’ve brought to America and the world that doesn’t get addressed the way that I feel it could.23

Hendricks’s comments throw into relief histories of objectification and commodification that have framed the ways blackness has been represented, looked at and understood in the United States and across the black diaspora. His statement describes – as explained earlier – how representation solidifies blackness into particular categories and along particular narrative lines. As Cheng has noted, it is impossible to escape this history of racialised skin;24 however, Hendricks is not expressing a desire to escape it. In the alternative forms of expression manifested in the urban style of his subjects he also found them articulating a desire to see, and represent, the black body in a way that did not automatically recall and result in objectification. Despite its sitter’s lack of clothing, Family Jules, with its self-conscious focus on the exterior and on skin itself, expressively materialises Hendricks’s interest in surface aesthetics as a strategy that challenged and expanded these representational categories.

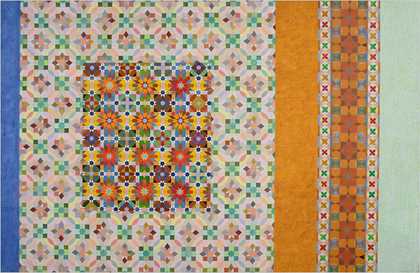

Fig.2

Sixteenth-century zellige tilework at the Ben Youssef Madrasa, Marrakech

Let us consider, for instance, the painting’s own surface aesthetics that emerge from Hendricks’s exploration of compositional arrangement. While Jules takes centre stage, around him Hendricks employs a form of recombination – a painterly bricolage that works to fill in the narrative. The composition is divided into three horizontal bands: at the top he has incorporated the geometry of Moroccan terracotta zellige tile designs (see fig.2), repurposed from photographs taken during his travels in the country. The middle band incorporates Jules on an imagined sofa (in the sense that it was not the same one Hendricks kept in his studio) and a shirt – the artist’s – that was added afterwards as ‘a figurative element that was a juxtaposing image for Jules’.25 The art nouveau-inspired pattern of this shirt recalls the work of Italian designers such as Fiorucci and Walter Albini who were incorporating these decorative elements into their clothing lines during this period,26 while the startlingly glossy lips that point towards the top of the painting also recall the glam aesthetic of 1970s fashion photographers such as Guy Bourdin.27 In the lower third of the painting Hendricks incorporates a rug bearing an oriental-style pattern that he had seen on a carpet at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts and photographed for future reference.28

The detailed geometric abstraction and figure–ground distinctions that are characteristic of Hendricks’s portraits are heightened here in the juxtaposition of the patterns with the vibrant block tones of Jules’s skin and the surface of the couch. These contrasts of pattern and colour were intentional, and intended as a way of exploring the materiality of space itself.29 We might see some similarities here with the food-laden canvases of Wayne Thiebaud, such as Cakes 1963 (National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.), as both artists explored spatial arrangement and the creation of depth through colour and the texture of pattern. In Family Jules this compositional situation – essentially a carefully arranged study of elements of design – is reinforced to some extent by the figure of Jules himself. His angular, burnished body set against the clean edges of the sofa and framed by the geometric patterns of tiles and rugs recalls the streamlined aesthetic of art deco that was creeping back into fashion at the time, along with the art nouveau-inspired pattern of the silk shirt. Both art deco and art nouveau were styles – like pop art – that emphasised the subtleties of surface and were directly connected to new forms of industrial production and consumption. They were also styles that proliferated through various forms of recombination and pastiche, using these in ways that served to heighten the visual appeal of surface.

Fig.3

Joyce Kozloff

Hidden Chambers 1975–6

Acrylic on canvas

1981 x 3048 mm

Private collection

© Joyce Kozloff

Hendricks’s use of pattern here falls somewhere between figuration and abstraction, and also corresponds with broader debates within the field of art history that arose in reaction to minimalism and conceptualism. Although the Pattern and Decoration movement only coalesced in the mid-1970s, its aims and ideas began to take hold in the 1960s, inspired by women’s liberation movements, queer culture and performance art. The Pattern and Decoration movement brought together artists from across the United States including Amy Goldin, Robert Zakanitch, Tony Robbins, Valerie Jaudon and Joyce Kozloff among others. It responded directly to the hierarchy of the art world that placed fine art above other forms of art making, including applied art and design. These artists were reacting against what they saw as the increasingly restrictive formalist discourses in art history framed by minimalism and conceptualism. Emphasising pattern and decoration was a political move that they believed could expand contemporaneous debates about form and aesthetics by incorporating new visual sources – these artists were particularly interested in non-Western art forms – and offering new ways of looking that emphasised multiple perspectives, a certain kind of experiential viewing, and the importance of technique and craft (see, for instance, Joyce Kozloff’s Hidden Chambers 1975–6; fig.3). Drawing on feminist politics and artworks and motifs traditionally defined (and marginalised) as feminine or women’s art, the movement’s aesthetic focus, aimed at broadening the formal language of art, was mirrored by its political focus on inclusivity. This is particularly evident in the collage aesthetic shared by several of its artists, in their utilisation of a broad range of source material, their employment of pastiche and hybridisation, and their embrace of materials often considered common or impermanent. The expansive nature of their references suggests how the movement in many ways reflected the postmodern cultural shift of the 1970s towards plurality both in the art world and in American society more widely.

In Family Jules, Hendricks’s integration of pattern from a variety of sources certainly resonates with the assemblage aesthetic of this movement; so, too, does his use of the grid – repeated in the tiles and hinted at in the rug – as a way of organising the decorative aspects of the painting geometrically within the overall composition. This experimentation with abstraction and figuration certainly overlapped with the formalist concerns of the period – championed by the critic Clement Greenberg – that emphasised the flatness of the support and its attendant optical experience.30 The flatness of Hendricks’s canvases takes us in another direction, one that emphasises the physical experience of colour, texture and paint itself to create a connection between the surface of the canvas and the body as surface – a connection that reinforces the eroticism of Jules’s posture and the pleasures of self-display. Furthermore, unlike Hendricks’s three earlier portraits of Jules (Jules 1971, private collection; George Jules Taylor 1972, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.; and New Orleans Niggah 1973, National Afro-American Museum and Cultural Center, Wilberforce), in this painting the relationship between foreground and background – articulated often in the interplay of sheen and matte surfaces – is reoriented horizontally into bands of alternating pattern and colour. This arrangement creates various focal points across the painting, requiring the viewer to move visually across its surface slowly, taking in the complex and variegated internal rhythms and intervals through which the painting is composed. Pattern fills space and compels a focus on structure: although the human eye has a tendency to seek a single point of reference or perspective, we are, in fact, given multiple viewpoints across the surface of the painting. We are encouraged to scan this painting rather than look through it, moving slowly across its surface to understand we cannot grasp it fully in one single glance. Rather than inhabit a disembodied position of perception as encoded in single-point perspective, we come to experience the visual order of the painting itself.

Situating Family Jules in relation to the Pattern and Decoration movement sheds light on the ways in which this painting participated in broader aesthetic debates of this time. Family Jules expands the formal languages of art during the 1970s: its unique form of realism and emphasis on surface aesthetics challenged, and still challenges, modernist tendencies to downplay the innovation and experimentation of representational painting and to narrowly restrict the terms and meanings of abstraction. In this way Family Jules also anticipates more recent scholarship on the 1970s art world that seeks to expand the frameworks by which we have come to view the period and the meanings we associate with histories of figuration and abstraction. Moving between these categories in Family Jules, Hendricks refuses a relationship of background and foreground that depicts a subject’s ‘substance’ (only) through the illusion of depth. Instead, he uses the materiality of surface – here revealed in the texture of paint and colour – to hold onto, and ground, the materiality of the body on view.