Fig.1

Artists at work in the Omega Workshops c.1913–19

Unidentified photographer

Bell made Abstract Painting c.1914 (Tate T01935) during a particularly convivial phase of her life. At this time she was enjoying the solidarity of her circle of friends, the Bloomsbury group, and she was working closely with other artists, notably Duncan Grant and Roger Fry. They painted together, often from the same subject, and they were co-directors of the Omega Workshops Ltd, the interior design company that Fry established in 1913. A photograph of the Omega studio from around 1913 draws attention to the communal spirit of the enterprise, projecting an atmosphere of camaraderie that was central to the company’s ideology (fig.1). Indeed, the principle of collaboration was so important that all work was submitted unsigned to a central pool, to be identified only by the company logo.

Bell’s abstract paintings were not pooled in this way, but they grew out of her designs for Omega textiles and belonged to the same culture of creative collaboration.1 She worked on them alongside Fry and Grant, to the extent that Grant later said that he could not remember who had first led the way toward absolute abstraction.2 The episode lasted just a few months, from the autumn of 1914 into 1915, after which all of the Bloomsbury artists returned to a more figurative style. Their surviving abstracts are small in number but significant. They include works such as Grant’s Abstract Kinetic Collage Painting with Sound (fig.2) and Fry’s Essay in Abstract Design (fig.3), as well as Abstract Painting and the handful of Bell’s other abstracts.3

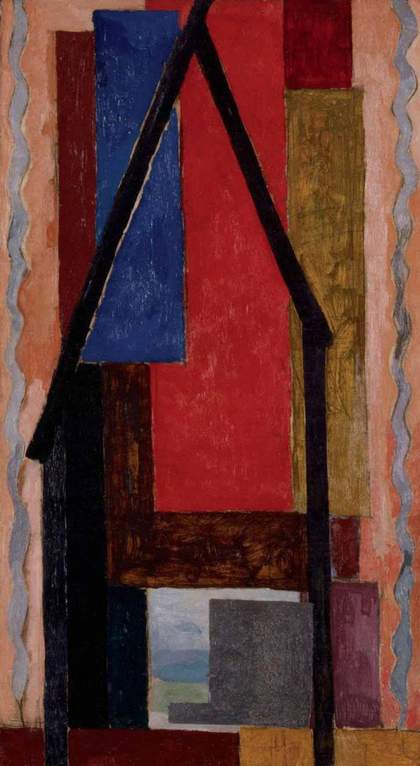

Fig.2

Duncan Grant

Abstract Kinetic Collage Painting with Sound 1914

Gouache and watercolour on paper on canvas

Tate T01744

© The estate of Duncan Grant

Photo © Tate

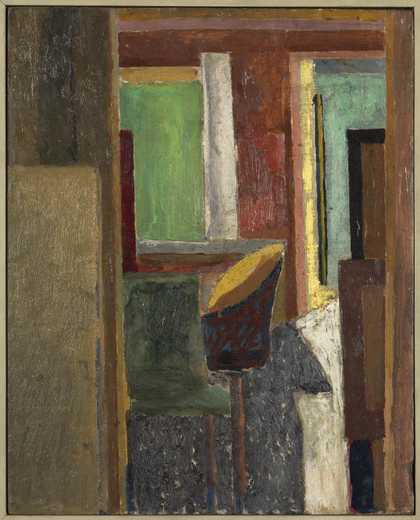

Fig.3

Roger Fry

Essay in Abstract Design 1915

Oil paint and bus tickets on wood

Tate T01957

Photo © Tate

There are distinct similarities between the Bloomsbury abstracts that mark them as belonging to the same corpus: their geometrical structures and rich colours;4 the use of cubist techniques of collage and papier collé, which Bell encountered when she visited Picasso’s studio in early 1914;5 and the fact that there is a core of work that is entirely non-representational. They are therefore often discussed together as a collective statement of Bloomsbury’s reaction to European modernism, their experiments in modern living, or indeed, their lack of enthusiasm for abstract art. However, as the art historian Simon Watney notes, ‘Bloomsbury abstraction does not present us with a single unified style’.6 There are variations within this body of work that point to differences of preoccupation among the artists, and which are accentuated by their very proximity. This essay will examine these variations with a view to establishing the distinctive qualities of Bell’s abstracts within the Bloomsbury corpus, and the ideas they might convey.

The core of the argument here depends on a distinction that can be drawn between Bell’s abstracts and those of Grant, broadly defined as the social versus the architectural. Grant made dense, crowded compositions which evoke built structures, both overtly, through devices such as the peaked roof shape that occurs in Abstract Kinetic Collage and In Memoriam: Rupert Brooke 1915 (fig.4), and inferentially, through the effect of collapsing columns in Abstract Kinetic Collage and the diagrammatic sequence of differently coloured ‘rooms’ in Abstract Composition 1915 (Hoffmann Collection, Berlin). Their close relationship with a semi-abstract collage such as Interior at 46 Gordon Square c.1915 (fig.5), which uses the same technique to delineate a view across a room, encourages us to read into them the spatial preoccupations of an architectural plan.

Fig.4

Duncan Grant

In Memoriam: Rupert Brooke 1915

Yale Centre for British Art, New Haven

Fig.5

Duncan Grant

Interior at 46 Gordon Square c.1915

Oil paint on wood

Tate T01143

© The estate of Duncan Grant

Photo © Tate

Bell’s abstracts, on the other hand, draw our attention to the relationships between shapes, whether grouped together or suspended in isolation. Whereas Grant crammed his surface with an all-over patchwork of shapes, Bell floated them against a more or less uniform background, creating effects of space and separation, and the ‘monolithic’ sense of scale that Watney observes in Abstract Painting.7 Within that space, shapes hang singly or cluster together in a block. In Abstract Painting the brick-red rectangle is the smallest shape in the picture, but its placement, alone and in the centre of the canvas, gives it a disproportionate significance. The pale pink square at the top right competes for our attention, conspicuously different in colour and shape. It holds in balance the outgrowth of rectangles in the opposite corner, which combine in a jagged mass of contrasting and complementary colours.

‘Bloomsbury’s painters imagined an alternative domesticity’, the art historian Christopher Reed has argued, but in the case of Grant’s abstracts, it is one without inhabitants.8 His rooms are empty. The sofa in Interior is unoccupied. In Memoriam, which was so titled retrospectively, after the death of the poet Rupert Brooke in April 1915, is precisely about the loss of a living presence. Like a tomb, it substitutes an architectural structure – the black outline of walls and roof – for the human body. By contrast, Bell’s abstracts suggest the human, not through direct representation but through an association with her own portraits and figure studies, and with the theories of political and social relationships that were formulated by her friends and debated among them.

Fig.6

Vanessa Bell

Frederick and Jessie Etchells Painting 1912

Tate T01277

© Estate of Vanessa Bell, courtesy Henrietta Garnett

Photo © Tate

The abstracted portraits and group paintings that Bell made in 1912–13 opened the way for her ‘purely abstract’ paintings and collages in several ways.9 As noted by her biographer Frances Spalding, the blank, geometrical shapes in her abstracts were the ‘logical outcome’ of her practice of simplifying the human form to the point where she eliminated facial features altogether.10 The backgrounds of her portraits also demonstrate a trajectory toward abstraction, from Frederick and Jessie Etchells Painting 1912 (fig.6), in which the garden view is rendered as broad, flat bands of colour, to the entirely abstract setting of Mrs St John Hutchinson 1915 (Tate T01768), which echoes the cluster of rectangles in Abstract Painting, as well as its palette of blue, yellow and red.11

Elsewhere in this In Focus project, the art historian Claudia Tobin argues that Abstract Painting still bears the trace of its origin in portraiture; that the red rectangle at its centre ‘can be understood as an abbreviation, even a denial, of the faces that occupied the focal point’ of portraits such as Virginia Woolf 1911–12 (National Portrait Gallery, London).12 Far from achieving absolute pictorial autonomy, Bell’s abstracts are haunted by human subject matter. Here I would extend this reading to argue that they echo the preoccupations of her group portraits in particular. In these ‘conversation pieces’ Bell explores the relationships between people in compositions that are both formalised and atmospheric. The details of facial expression, costume and environment are erased. Instead, subtle effects of intimacy and isolation, conversation and companionable silence, are conveyed through her subjects’ demeanour – their shape in profile – and their configuration across the canvas.

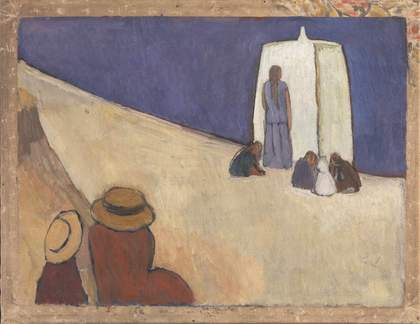

Fig.7

Vanessa Bell

Studland Beach c.1912

Tate T02080

© Estate of Vanessa Bell, courtesy Henrietta Garnett

Photo © Tate

Bell’s move toward abstraction in her figure painting achieves ‘the distillation – rather than the rejection or transcendence – of social experience’, as the art historian Lisa Tickner demonstrates in her brilliant analysis of the sequence of paintings that culminated in Studland Beach c.1912 (fig.7).13 Tickner shows how the latter painting’s ‘self-conscious geometry’, the way in which the two figures in the foreground draw together in ‘a single bisected shape’, creates a sense of ‘emotional contact’ between the subjects.14 The composition also generates an atmosphere of ‘pervasive melancholy’ by isolating figures against the yellow-white of the sand and bathing tent, whether singly or in groups.15 In Summer Camp 1913 (fig.8), by contrast, the geometry of the group holds it together in an easy familiarity. A pentagon of figures – I identify the fifth as the unseen artist or viewer, situated below the bottom edge of the picture – revolves around the pivotal point of the woman in blue, the v-line of her dress rhyming with the triangle of the tent behind and the forks of her companions’ knees. Other paintings in this set, such as Conversation at Asheham House (fig.9) and A Conversation 1913–16 (Courtauld Gallery, London), explore the dynamic between three figures in which one, set apart, commands the attention of the others. In all these paintings, the configuration of subjects, in groups or in isolation, evokes the arrangement of shapes, single or clustered together, in Bell’s abstracts.

Fig.8

Vanessa Bell

Summer Camp 1913

Bryan Ferry Collection

© Estate of Vanessa Bell

Fig.9

Vanessa Bell

Conversation at Asheham House 1912

University of Hull Art Collection, Hull

© Estate of Vanessa Bell, courtesy Henrietta Garnett

Photo © University of Hull Art Collection, Humberside, UK / Bridgeman Art Library

There is a politics to Bell’s conversation pieces that also pervades her abstract paintings: the politics surrounding ‘the relationship of a part to the whole’ that the literary historian Regenia Gagnier identifies as ‘the key tension of the period’.16 Reed and others have shown how the defence of individual liberty underpinned the Bloomsbury group’s thinking in a number of areas, political and aesthetic alike.17 As Reed observes: ‘The desire to ground modernism in anti-authoritarian individualism was fundamental to Bloomsbury’.18 They rejected prescriptive structures of thought and social organisation: grand theories, consistent styles, artistic groups with memberships and manifestos. Instead, they cultivated the loose, informal, improvised model of the conversation, which tolerates and indeed depends on difference, and assumes a more or less equal relationship between the participants.19

In Bell’s group portraits, these patterns of speech and of social organisation play out in her sketches of friends at home, talking or just being together, at their ease. In her abstracts, they are ‘distilled’ in the patterning of shapes across the canvas, and the ways in which colours and shapes modify each other in juxtaposition. Abstract Painting is not a manifesto for individualism: for Bell that would have been too formulaic. Yet it does pose the question of how a part might relate to the whole without being subsumed into it; of how a pink square speaks to a maroon oblong across an expanse of yellow, and how all these shapes and colours adapt to the exchange. The painting is, fundamentally, a study in relationships, and the ways in which meaning is generated through differentiation.20 That is surely what Bell meant when she later described the work as a ‘Test for chrome yellow’.21