The abstract movement was a colossal development in Western art, with a global impact that continues to unfold. As the curator Leah Dickerman explained in the catalogue to the 2012 exhibition Inventing Abstraction 1910–1925: How a Radical Idea Changed Modern Art (Museum of Modern Art, New York), it ‘amounted to as great a rewriting of the rules of artistic production as had been seen since the Renaissance’.1 It was correspondingly competitive, to the extent that some early examples of abstract work were later backdated.2 Vanessa Bell did not claim priority in this way, but her advocates have nonetheless emphasised her originality as an abstract artist. Art historian Lisa Tickner asserts that Bell’s experimental work of 1914 was ‘in the forefront of early modernism: neither Picasso nor Braque made the same move to abstraction in their collages’,3 while art historian Richard Shone insists that ‘in 1914 Bell had seen virtually no non-figurative work by other artists’, and that her abstracts derived solely from her own painting and decorative design.4

Fig.1

Vanessa Bell

Abstract Painting c.1914

Tate T01935

Yet as Dickerman points out, there are other, potentially more productive ways of assessing the role of individuals in the abstract movement. Abstraction was not the brainchild of an isolated genius. Rather, according to Dickerman it was ‘an invention with multiple first steps, multiple creators, multiple heralds, and multiple rationales’, the pioneers of which were ‘far more interconnected than is generally acknowledged’.5 This essay will situate Bell’s Abstract Painting c.1914 (Tate T01935; fig.1) within the international abstract movement, not by demarcating her unique achievement, but by exploring the connections between her work and those of other abstract artists across Europe.

By the time Bell was working on Abstract Painting in the autumn of 1914, the practice of abstraction had spread rapidly and widely across Europe and North America, involving many of the major players in the modernist movement. The ground had been prepared gradually over many decades, but the key developments occurred within the space of two or three years, and with explosive impact on artists and their viewers.6 The break with the depiction of external subject matter came in December 1911, when Wassily Kandinsky showed Composition V 1911 (private collection) at the first Blaue Reiter exhibition in Munich, and published Concerning the Spiritual in Art (Über das Geistige in der Kunst) as a manifesto for abstraction. During 1912 a handful of other artists joined the pursuit. In February Arthur Dove showed a series of pastel abstracts in New York, in which the forms were an ‘extraction’, as he later put it, from the material of daily life.7 In July Robert Delaunay exhibited his semi-abstract Windows (Les Fenêtres) series in Zürich, with its prismatic, polychrome shattering of views through a window. And in October, Francis Picabia, Fernand Léger and František Kupka all showed radically abstract works at the Salon d’Automne in Paris.8

Thereafter the movement escalated. Bell’s discovery of abstraction may have been made independently, or semi-independently, but she shared it with dozens of other artists. By the end of 1914 these included Kandinsky’s collaborators in the Blaue Reiter group, among them Auguste Macke who, like Bell, used abstraction to analyse colour combinations and their interaction with different shapes and textures. The worldly, iconoclastic vision of the Italian futurists promoted abstraction as an art of modern life. In Russia, Natalia Goncharova and Mikhail Larionov invented rayonism, which depicted the rays of light striking an object rather than the object itself. In Paris, then considered the global capital of the arts, artists of many nationalities joined the abstract revolution: the Dutchman Piet Mondrian, whose move to radical abstraction began with his tree series of 1912; the Ukrainian-born Sonia Delaunay-Terk, who in 1913 collaborated with the poet Blaise Cendrars to make an abstract book, Prose on the Trans-Siberian Railway and of Little Jehanne of France (La Prose du Transsibérien et de la petite Jehanne de France) (Tate P07355); and the Finnish painter Léopold Survage, who made Coloured Rhythm (Rhythme coloré) 1913 (Museum of Modern Art, New York) as an early contribution to the new art of cinematography.

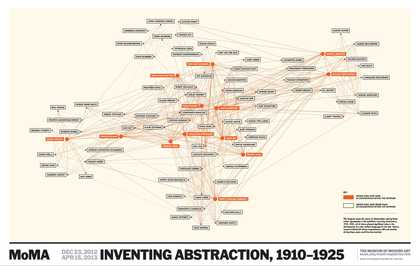

Fig.2

Inventing Abstraction 1910–1925: Connections

Interactive digital map created for the 2012 exhibition Inventing Abstraction 1910–1925: How a Radical Idea Changed Modern Art, Museum of Modern Art, New York

These artists and many others participated in the international community that constituted the abstract movement. The interwoven nature of that community is demonstrated by the diagram of personal acquaintance which was created for display in Dickerman’s Inventing Abstraction exhibition and which enmeshed over eighty artists across Europe and America in an intricate cat’s cradle of encounter and collaboration (fig.2).9 Bell herself is linked directly with Pablo Picasso, Goncharova and Larionov, and the vorticist group in London (specifically Percy Wyndham Lewis, David Bomberg, Henri Gaudier-Brzeska and Lawrence Atkinson), as well as with Duncan Grant from her own Bloomsbury group.10 One should also add her friend Roger Fry, both as an abstract artist in his own right and as one of the ‘connectors’ whom the diagram highlights as instrumental in the process of linking people and disseminating material.11 Fry’s work as a curator, bringing modern European art to London, and his critical defence of ‘post-impressionism’, as he loosely termed the new art, gave Bell access to art and ideas that transformed her creative practice.

Connectors enable associations between people whose paths might never otherwise cross. Bell had no direct contact with abstract artists such as Delaunay-Terk or Jean (Hans) Arp, or with the poet and critic Guillaume Apollinaire, but she knew Picasso and his work, and he knew and worked creatively with all of these people. The abstract movement was an ‘imagined community’ in the historian Benedict Anderson’s sense of the term – one held together by knowledge of one another’s work and ideas, and by the virtual meeting places of galleries and publications.12 Like the ‘imagined community’ of the nation state, but unconfined by national borders, it flourished under certain conditions.13 Modern transport (steam-powered trains and boats, and the first automobiles), communication technologies (the telegraph, telephone and radio), a phenomenally efficient and coordinated global postal service, the cheap mass-production and circulation of print media, notably art journals and ‘little magazines’ (small-scale publications promoting new art), a burgeoning exhibition culture and the arrival of international loan exhibitions: all of these enabled people, images and ideas associated with the abstract movement to move rapidly across the western world.

As a well-travelled woman living in London, deeply involved in the modern art movement, with the time and means to visit galleries and her own work included in several major exhibitions, Bell was ideally placed to track the international abstract movement as it unfolded.14 Take, for example, her letter to Grant of 25 March 1914, recounting ‘a most successful time in Paris’ where her party, which included Fry, ‘had a very exciting time with pictures’.15 They visited the modernist writer and salon hostess Gertrude Stein – another connector – whose collection of modern art included works by Cézanne, Picasso, Braque and Matisse, and who took them to visit Picasso in his studio. They also saw the collection of Michael Stein (Gertrude’s brother) and Matisse’s studio, and visited the major dealers in modern art: Daniel-Henri Kahnweiler, where they ‘saw the Picasso you liked’;16 and Ambroise Vollard, to whom Fry proposed an exhibition of modern art showing new artists alongside Cézanne and the impressionists. Projected for the winter of 1914, but presumably curtailed by the outbreak of the First World War, it would have completed a trilogy of post-impressionist exhibitions at the Grafton Galleries, London.17 ‘It seemed rather a good idea’, commented Bell.18

Fig.3

František Kupka

Amorpha, Fugue in Two Colours (Amorpha, fugue à deux couleurs) 1912

Národní Galerie, Prague

Fig.4

Pablo Picasso

Pots and Lemon (Pots et citron) 1907

Batliner Collection, Albertina Museum, Vienna

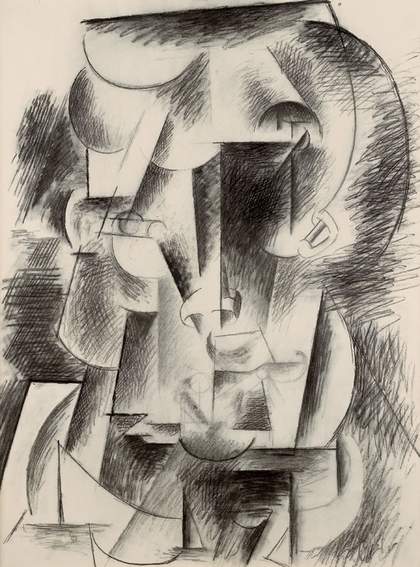

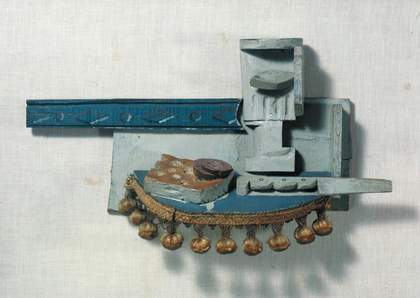

What works might feature in an exhibition curated around the theme of Vanessa Bell and the International Abstract Movement? A priority would be the radically abstract paintings that Bell would have seen at the Salon d’Automne of 1912, such as Kupka’s Amorpha, Fugue in Two Colours (Amorpha, fugue à deux couleurs) (fig.3), which caused such a stir in the international press.19 Picasso would be crucial, despite his ambivalence about abstraction.20 We would certainly request his cubist Pots and Lemon (Pots et citron) 1907 (fig.4), which Bell and her husband Clive Bell bought from Kahnweiler in 1911. For Clive Bell, this work epitomised the priority of form over subject matter which, he argued, distinguished real art.21 In 1912 Kahnweiler loaned thirteen Picassos to Fry’s Second Post-Impressionist Exhibition, which also included works by Vanessa Bell.22 In his preface to the catalogue Fry traced a trajectory within the selection, from the early, figurative portraiture to the radical abstraction of cubist works such as Picasso’s Head of a Man (Head with Moustache) (Tête d’Homme (Tête Moustachue)) of 1910 or 1912 (fig.5).23 When Bell visited Picasso’s studio in Montparnasse, she described his papiers collés as ‘amazing arrangements of coloured papers and bits of wood which somehow do give me great satisfaction’.24 With reference to this, we might select a collage such as the 1914 Still Life (Nature morte) (fig.6), with its arrangement of painted wood and upholstery fringe, for our wall of Picassos.

Fig.5

Pablo Picasso

Head of a Man (Head with Moustache) (Tête d’Homme (Tête Moustachue)) 1910 or 1912

Charcoal on paper

Fondation Beyeler, Basel

Fig.6

Pablo Picasso

Still Life (Nature morte) 1914

Tate T01136

© Succession Picasso/DACS 2016

Photo © Tate

Kandinsky was key to the development of abstract art in Britain and his reception there suggests new ways of thinking about Bell’s Abstract Painting.25 His work was available to her in exhibition throughout her experimental phase, and art historian Simon Watney notes a similarity between the woodcut version of her painting The Tub 1917 (Tate T02010) and Kandinsky’s woodcuts.26 Kandinsky first began showing in London in 1909 with the Allied Artists’ Association (AAA), an exhibiting society modelled on the progressive, international Salon des Indépendants. It was the ‘pure visual music’ of his submission to the AAA of July 1913 that converted a sceptical Fry to the possibilities of abstract art.27 Fry explained that he could no ‘longer doubt the possibility of emotional expression by such abstract visual signs’ as he found in, for example, Kandinsky’s Improvisation 29 1913 (Albright–Knox Art Gallery, New York). When Fry stayed with the collector Michael Ernest Sadler earlier that year, Sadler wrote to Kandinsky that Fry had been ‘deeply interested in your drawings. He asked if I would lend them for an exhibition which he and some friends are organising next week in London, and of course I gladly consented’.28 Fry did indeed show two watercolours by Kandinsky at the first Grafton Group exhibition of March 1913. Only one of these is now identified,29 but Sadler’s collection of Kandinsky’s work was extensive and included abstracts such as Fragment II for Composition VII 1913 (Albright–Knox Art Gallery, New York), which we would wish to borrow for our survey exhibition.

Fig.7

David Bomberg

In the Hold c.1913–14

Tate T00913

Photo © Tate

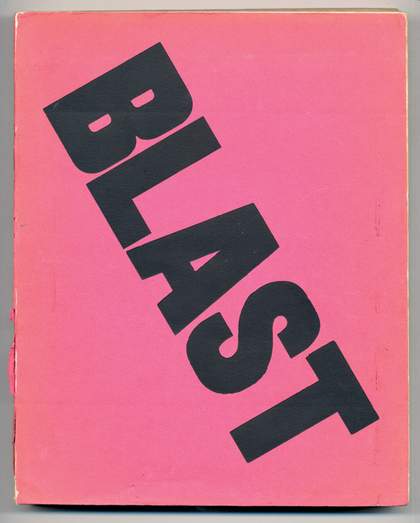

Our exhibition would also stretch to include ‘the opposition’ to Fry and Bloomsbury that became the vorticist group, and that answered the challenge of futurism with angular abstractions emphasising the arrested energy of modern life, rather than its speed and mobility.30 Bell had the opportunity to see works such as Bomberg’s painting In the Hold c.1913–14 (fig.7) and sculptures including Gaudier-Brzeska’s Red Stone Dancer c.1913 (Tate N04515) and Jacob Epstein’s Female Figure in Flenite 1913 (Tate T01691) at various exhibitions in London, sometimes alongside her own work.31 She would doubtless also have seen a copy of the vorticist magazine Blast (fig.8) which came out in July 1914, and which reproduced a number of vorticist works including Lewis’s Portrait of an Englishwoman in ink, pencil and watercolour of 1913 or 1914 (fig.9), with its bold colour contrasts and rhythmic configuration of rectangles.32 Fry and his circle were ostentatiously excluded from vorticist platforms, and excluded Lewis and his allies in their turn, but vorticism was nonetheless a presence and a stimulus in Bell’s visual world, even if she found Lewis’s political manoeuvrings ‘inconceivably stupid’.33

Fig.8

Percy Wyndham Lewis

Cover of Blast, no.1, 1914

Courtesy The Poetry Collection, State University of New York at Buffalo

© Wyndham Lewis and the estate of Mrs G.A. Wyndham Lewis by kind permission of the Wyndham Lewis Memorial Trust

Fig.9

Percy Wyndham Lewis

Portrait of an Englishwoman 1913 or 1914

Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford, Connecticut

© Wyndham Lewis Memorial Trust

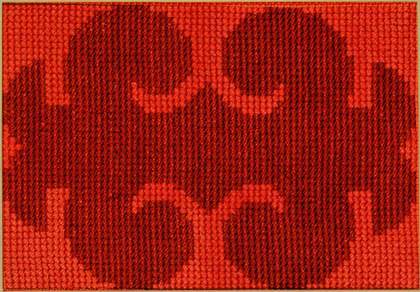

Our exhibition could culminate in a selection of work by European artists who, like Bell, developed their abstract practice in creative partnerships. Robert Delaunay and Sonia Delaunay-Terk used colour contrasts to create effects of pattern and movement in their abstract painting, as is evident in Robert Delaunay’s The Cardiff Football Team (L’Équipe de Cardiff) (fig.10), which Bell would undoubtedly have seen in 1913 at the Post-Impressionist and Futurist Exhibition (Doré Galleries, London). Jean Arp and Sophie Taeuber-Arp worked at the intersection between abstract painting and decorative design, as did Bell at Roger Fry’s decorative arts company Omega Workshops Ltd. Arp responded to the cubist technique of papier collé by sewing abstract designs in needlepoint (see After a collage (À la suite d’un papier collé) 1914; fig.11), while Taeuber-Arp translated her geometrical abstractions into embroideries such as Vertical-Horizontal Composition (Composition verticale-horizontale) 1916 (fig.12). Such parallels between artists fit the pattern of multiple, converging inventions that characterised the abstract movement as a whole, and that militate against a narrative of singular innovation.34

Fig.10

Robert Delaunay

The Cardiff Football Team (L’Équipe de Cardiff) 1913

Stedelijk van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven

Fig.11

Jean (Hans) Arp

After a collage (À la suite d’un papier collé) 1914

Stiftung Hans Arp und Sophie Taeuber-Arp e.V., Remagen-Rolandswerth

Fig.12

Sophie Taeuber-Arp

Vertical-Horizontal Composition (Composition verticale-horizontale) 1916

Fondazione Marguerite Arp, Locarno

More than anything, however, our exhibition would leave an impression of stylistic miscellany, and of the absence of any visual relationship between Bell’s Abstract Painting and the various models on which she might have drawn.35 She may have seen these works, or ones like them, but they were clearly not the direct inspiration for her own abstract compositions. Historians have therefore looked to other, more immediate sources, namely her designs for the Omega Workshops and the simplifying tendency in her figurative painting from around 1912 onwards.36 These different aspects of her own practice are certainly relevant, and the art historian Christopher Reed makes a compelling case for the political implications that Bell’s abstract paintings acquired through their domestic associations.37 However, I would contend that her response to European abstraction was stronger than might appear from the visual evidence, and that the key to the connection lies in the extensive literature that surrounded the abstract movement and in the strong theoretical current that propelled its innovations. Like the Arts and Crafts, for example, and unlike art nouveau, abstraction was not stylistically or technically unified as a movement. Rather, it was held together by personal connections, shared ideas and the challenge posed by the concept of abstract art – what Dickerman calls ‘the sheer difficulty of thinking such a radically new idea’.38

Bell had access to writing about abstraction, as well as to abstract art, before she tried her hand at the genre, and she and her friends debated the new art intensely. The voluminous textual response to abstraction played a large part in defining the challenge. For example, she would have read Fry’s prediction in his introduction to the catalogue of the Second Post-Impressionist Exhibition that the ‘logical extreme’ of modern art ‘would undoubtedly be the attempt to give up all resemblance to natural form, and to create a purely abstract language of form’.39 She would probably have read his review of the AAA exhibition of 1913 in which he celebrated Kandinsky’s ability to create ‘complete pictures’ out of the interplay of form and colour alone.40 She could have read about Kandinsky in other publications too: in the ‘little magazine’ Rhythm, where an article of 1912 by Michael T.H. Sadler (son of Michael Ernest Sadler and later known as Michael Sadleir) presented the first discussion in English of Kandinsky’s Concerning the Spiritual in Art; in the younger Sadler’s translation of the book, published in April 1914 as The Art of Spiritual Harmony; and in the artist Edward Wadsworth’s review of the book, which appeared in the first edition of Blast.41

Kandinsky’s writing, mediated by his English commentators, suggests ways of thinking about Bell’s Abstract Painting and of bringing it into conversation with the wider abstract movement. Sadler warned against the tendency for abstract art to become ‘pure pattern-making’, an exercise in decoration.42 He was drawn instead to Kandinsky’s theory that abstraction intensifies the expressive qualities of an image because it conveys the ‘inner soul of persons and things’, rather than the ‘outer conventions of form and colour’.43 It is a question that conditions the debate surrounding Bell’s abstract paintings: whether, as art historian David Peters Corbett has complained, she presents ‘only colour, pigment and composition within a decorative order’, a technical exercise that, according to Richard Shone, convinced her intellectually but not emotionally;44 or whether, as Fry argued, she was committed above all to ‘the process of trying to express an idea’, an idea that Reed takes to be that of modernity itself.45

The evidence in the work is subjective. Abstract Painting may or may not induce a spiritual vibration of the sort that Kandinsky anticipated. Furthermore, as Reed reminds us, there is no visual connection between the Bloomsbury artists’ geometrical compositions and Kandinsky’s swirling improvisations.46 Yet Wadsworth quotes Kandinsky’s dictum that ‘form alone, even if it is quite abstract and geometrical, has its inner timbre’, while Sadler’s account of Kandinsky’s psychological theory of colour, and the ways in which colours relate to each other ‘both singly and in combination’, recalls the arrangement of coloured shapes in Abstract Painting, either clustered together in the corner or floating in isolation across the canvas.47 The idea of abstraction, communicated verbally through texts and discussion, seems just as likely a source for Bell’s painterly experiments, perhaps even more so than the practical examples to which she had access.

Abstract Painting ‘firmly marks [Bell’s] allegiance to a European avant-garde’, as Watney asserts.48 It does so by presenting an original solution – one of many original solutions – to a problem that was shared by artists across Europe: namely, how to realise the idea of an entirely non-figurative art. The fact that Bell participated in such a wide-reaching debate about abstraction, which played out through texts as well as images, need not diminish the scale of her own achievement. Rather, it widens the possibilities of interpretation, suggesting a set of contexts and connections for a phase of her career which, as Sadler warned in his assessment of the abstract movement as a whole, ‘leads nowhere’ when seen in isolation.49