Vanessa Bell’s abstract phase of 1914–15 coincided with her employment at Roger Fry’s Omega Workshops, a collective of artists established in 1913, where she undertook a range of decorative work, including textiles, ceramics, painted furniture and murals. The writer Peter Wollen has suggested that this link with the decorative has deflected attention from the Bloomsbury artists’ abstract canvases, a neglect that the art historian Christopher Reed seeks to address in his discussion of the Bloomsbury group and domesticity.1 This essay examines the interaction between Bell’s painterly and applied abstracts in more detail, arguing that this porous relationship comes into focus in the context of the Omega revolution in British interior design, but also in a larger, international framework in which female modernist designers were renegotiating the borders of the fine and decorative arts. It also looks at how encounters with the non-European, specifically with Middle Eastern textiles, enabled European modernists to rethink basic aesthetic categories.

The Omega contributed to debates about the meaning of the decorative and its significance for modern painting at a time when abstract painting was criticised on the grounds that it was ‘acceptable as design’ but ‘unsuitable as art’.2 As a departure from the ‘fatal prettiness’ deplored by Bell and her circle, the Omega sought to revolutionise the aesthetics and ultimately the values of the English interior with an approach to design informed by the new chromatic and formal freedoms of post-impressionism.3 The elevation of the applied arts alongside painting underpinned Fry’s vision. He objected to the ‘rigid distinction’ between them and asserted that artists could easily do the work of artisans.4 By the 1920s he was arguing that the Omega demonstrated the influence of abstract painting on design, with artists attempting to limit themselves to the ‘simplest forms’.5 However, critics have debated the nature of the exchange. Reed makes the case that the decorative arts freed the Bloomsbury artists from ‘conventions of figuration in easel painting’.6 Here it will be argued that Bell’s work for the Omega reveals a bilateral exchange with her abstract painting – a ‘flexible association’, to use art historian Matthew Affron’s useful term – which presents both visual similarities and affinities in processes of making.7

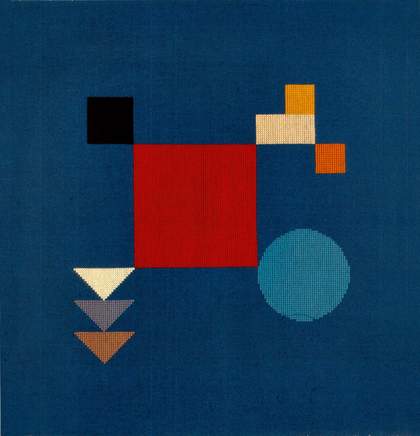

Fig.1

Vanessa Bell

Abstract Painting c.1914

Tate T01935

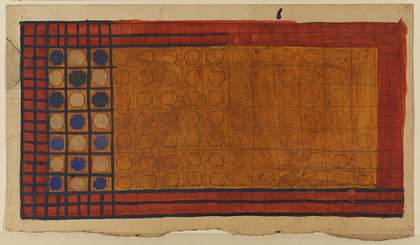

Fig.2

Vanessa Bell

Maud 1913

Printed linen

Victoria and Albert Museum, London

© Victoria and Albert Museum

The association between Bell’s abstracts and her work for the Omega is particularly evident in her textile designs. Omega artists produced painted silk scarves, furnishings, fabrics, carpets and embroideries, and a range of six printed linens in different colourways.8 Abstract Painting c.1914 (Tate T01935; fig.1) resembles fabric and furnishing designs such as Maud 1913 (fig.2), with its broken patches of bold colour set off by zigzagging black lines. Structural similarities are also evident in Bell’s gouache and pencil designs for a rug with dynamic black diagonals, the ‘Lady Hamilton rug’ of 1914 (Victoria and Albert Museum, London, where it is known as Carpet). One of these designs (Courtauld Gallery, London) is made on paper with gridded squares, revealing an interest in line and structure that equally informs her abstract painting.9

Bell’s use of colour in her works on canvas and cloth reveals further affinities on the level of facture. She was attentive to the spatial organisation and application of colour in the years leading up to her work for the Omega. Following visits to see Byzantine mosaics in Turkey and Italy during 1911–12, she described her attempt to paint ‘as if I were mosaicking … by considering the picture as patches, each of which has to be filled by the definite space of colour as one has to do with mosaic or woolwork, not allowing myself to brush the patches into each other.’10 Her use of analogies pertaining to different media anticipates the exchange in her practice between the applied and fine arts in the early years of the Omega. One design for Maud of 1913 (private collection) evokes a mosaic with its outlining of carefully applied black gouache on squared paper. On the other hand, the printed linens reveal painterly effects. As the curator Alexandra Gerstein has noted, they combine ‘the unfinished appearance of the hand-drawn line with areas of strong colour liberally applied to the surface’, and the majority were probably produced through stencil- or block-printing, or a combination of the two, rather than by machine.11 Examples of stencil-printing, an artisanal method whereby colour is brushed in through a stencil, and which therefore retains imperfections such as irregularly printed lines, can be observed in fabrics printed with Bell’s Maud and White designs of 1913 (both Victoria and Albert Museum, London). In the latter, the looseness of design, consisting of cloud-shaped patches of colour overprinted with a radiating palmette-like schema, is sympathetic to production by stencil, and there are what Gerstein describes as ‘patchy or stippled’ areas of colour on the back of the fabric, indicating the use of a brush.12

With eyes sharpened to the weave and weft of Bell’s Omega fabrics, we give greater attention to the texture and surface of her Abstract Painting. On closer observation, the field of yellow reveals flecks, stippling and dashes of lighter white-yellow paint, which highlight the weave of the canvas and animate the surface. This draws attention to the materiality of the linen canvas, reminding us that it is itself textile. The visibility of the weave in thinly painted areas also creates an effect suggestive of a pencil line delineating the coloured blocks, as if Bell had initially sketched or stencilled her design onto the canvas like one of her pattern designs. Furthermore, the uneven handling on the edges of the coloured oblongs and variation in the application of paint, for instance in the slightly more built up texture of the pink square, aligns this work more closely with the Omega ‘hand-made’ aesthetic.

Bell’s process of working simultaneously on cloth and canvas in the early days of the Omega would have allowed her to explore not only their affinities but also the differences and limitations. Designing and making textiles was demanding and time-consuming in a way that was different from painting. The printed fabrics might appear freehand and spontaneous, yet as the fashion and textile historian Valerie Mendes notes, ‘they meticulously conform to repeated pattern rules’.13 The idea that painting could be a liberating practice was expressed by Bell in the midst of her work for the Omega, when she confessed to Fry that ‘It’s rather fun painting after doing all these patterns’.14

The fact that women designers and painters played a central role in the reinvention of the applied arts in modernist circles suggests another way of situating Bell’s work in the context of international modernism. While André Mare and his circle of French artists represented what Reed calls ‘Bloomsbury’s nearest French contemporaries’, with their creation of modernist rooms in a cubist style, Fry’s fundraising letter for the Omega workshops in 1912 aligned them with Paul Poiret’s École Martine, which operated in Paris from 1811 to 1929, commissioning working-class girls to design murals, textiles and painted furniture.15 Bell’s Omega works also present strong parallels with designers of the Wiener Werkstätte, a community of artists and designers founded in Vienna in 1903, where the production of textile patterns and prints flourished during 1913–14.16 For instance, Bell’s simplified patterns and vibrant tones sit comfortably alongside Maria Likarz’s 1910/13 Ireland (Irland), with its floating rectilinear and geometric patterns and cross-cutting diagonals, and the vertical strips of bold colour in Vally Wieselthier’s Andromache pattern of 1919.17 Women remained at the forefront of European textiles over the subsequent decade, running the weaving workshops at the Bauhaus school established in Weimar in 1919, which positioned design at the heart of its project.

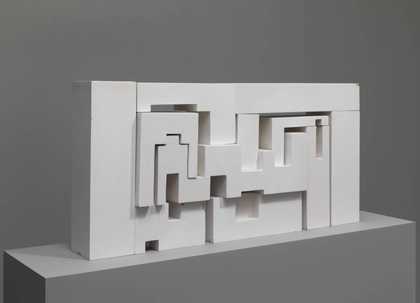

Fig.3

Sophie Taeuber-Arp

Untitled (Composition with Squares, Circle, Rectangles, Triangles) 1918

Stiftung Hans Arp und Sophie Taeuber-Arp e.V., Remagen-Rolandswerth

While many individual female artist-designers have been marginalised by art history, the work of Bell’s female European contemporaries has come increasingly into the foreground of reassessments of this period.18 Situating her work in this manner raises questions about the ways in which gender inflects the relationship between the fine and decorative arts. The sphere of textiles, long considered respectably feminine, was radically reinvented by the Swiss artist Sophie Taeuber-Arp and the German artist Hannah Höch, both of whom were involved with the dada art movement in the 1910s and 1920s. While the respective practices of Taeuber-Arp and Höch cross-fertilised painting and decorative work, unlike Bell they both received early formal training in textiles and this informed their involvement with dada experiments in new materials for painting.19 In 1915 Taeuber-Arp began collaborating with Jean (Hans) Arp, the French artist who later became her husband, making works that, as Arp described, ‘drew on the simplest of forms in painting, in embroidery and in paper collé’ and ‘rejected everything that was a copy or description … to allow the elemental and the spontaneous to react in full liberty’.20 At this time Taeuber-Arp was producing non-representational geometric paintings and watercolours, which recall Bell’s works of 1914–15, as we observe in the carefully structured geometric blocks of colour in her pared-down Vertical-Horizontal Composition (Composition verticale-horizontale) 1916 (Archive Stiftung Hans Arp und Sophie Taeuber-Arp e.V., Remagen-Rolandswerth). Like Bell in Abstract Painting, here Taeuber-Arp explored the relationship between square and rectangle in different colour combinations. Critics have suggested that her early geometric compositions in paint may have been patterns for textiles and embroideries, but that she became increasingly attracted toward the square as a model for non-representational painting.21 Her untitled embroidery of 1918 (known as Composition with Squares, Circle, Rectangles, Triangles; fig.3) has a large red square at its centre, with a striking effect similar to that of the red rectangle in Abstract Painting.

The Omega aesthetic has affinities with Höch’s work, which, according to art historian Ruth Hemus, makes reference to ‘the hand-made’ and to ‘domestic creativity’ but also to ‘repeatable models, patterns and principles’.22 Höch’s early practice, particularly from around 1917 when she was working with subversive collage and photomontage, confronted the more conservative gender stereotypes of the Weimar Republic, which promoted conventional roles for women as home-makers and child-bearers. Art historian Virginia Gardner Troy has suggested that embroidery enabled Höch ‘to investigate the boundaries between traditional “women’s work”, images of the New Woman and the hierarchical distinctions between fine and applied art’.23 Although Bell’s work was not overtly subversive, her elliptical, identity-blurring treatment of the portrait and her use of bold, non-naturalistic colour and abstract design during the pre- and interwar periods implicitly reassessed gender and artistic boundaries. Arguably, the Omega’s collaborative environment encouraged this fluidity since decorative work was produced not only by women trained in the applied arts, but also by male artists.

Of the female artists who developed pure abstraction during the pre-war period, Bell has the closest affinity with the Ukranian-born artist Sonia Delaunay-Terk. Delaunay-Terk applied the principles of ‘simultanism’ – her theory of rhythm and movement as generated by complementary colours – to painting and textile design and later to a range of decorative objects.24 She claimed that there was ‘no gap’ between her painting and her ‘decorative’ work; rather, the ‘minor arts’ represented ‘an extension’ of her art.25 She created her first ‘simultaneous dress’ (robe simultanée) in 1913 (private collection; later examples of the fabric are held in the Musée de l’Impression sur Etoffes, Mulhouse), developing the aesthetic of her ‘cubist’ blanket (couverture) of 1911 (Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris) to incorporate a patchwork of coloured cloths into an abstract pattern. Bell also began experimenting with ‘wearable’ art, in her case in the spring of 1915. She envisioned a line of unconventional dresses which would ‘use the fashions and yet not be like dressmakers’ dresses’, exploiting the effects of vibrant new hues imported from European fashion and costume design.26 She had been inspired by director Jacques Copeau’s theatre productions on a visit to Paris in March 1914, and her Maud design proved forward-looking as it was taken up by Grant in his costume designs for Copeau’s 1913 production of Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night in Paris, based on the director Edward Gordon Craig’s theories of abstraction.27

Like Delaunay-Terk, who according to art historian Petra Timmer used embroidery as ‘a means to break loose from the academic tradition of line structure dominating color’, Bell radically reconfigured the role of colour and line in the applied arts as in painting, although she did not adhere to specific colour theories.28 Over the next few years, she oversaw the Omega production of waistcoats, ‘avant-garde kimono-like painted cloaks’ and ‘vibrantly coloured silk stoles’, which blended fashion and decorative art.29 Virginia Woolf, Bell’s sister, supported her sartorial experiments at the Omega, but even she baulked at the audacity of her colour schemes in a letter of 1916: ‘What clothes you are responsible for! Karin’s clothes wrenched my eyes from the sockets – a skirt barred with reds and yellows of the vilest kind, a pea green blouse on top, with a gaudy handkerchief on her head, supposed to be the very boldest taste.’30

Fig.4

Sonia Delaunay

Design B53 1924

Gouache on paper

Private collection

Examining Bell’s abstraction in relation to her designer contemporaries underlines not only her cosmopolitanism and connections with European modernism, but also her anticipation of its celebrated developments. Delaunay-Terk’s textile and fashion houses, established in Madrid and Paris in 1917 and 1920 respectively, and her work for Metz and Co. in the mid-1920s, arguably represent a more sustained, commercially successful contribution to avant-garde embroidery and dressmaking than Bell’s work for the Omega.31 However, it was only when Delaunay-Terk produced designs for printed fabrics combining blazing colours and interlocking rectangles such as Simultaneous Fabric no.60 (Tissu simultané no.60) 1924 (Musée de l’Impression sur Etoffes, Mulhouse) and Design B53 1924 (fig.4) that we see patterns in her work that were as radically geometric as Bell’s of the previous decade. Omega artist Nina Hamnett testified to Bell’s pioneering experiments when she recalled the impact of wearing a jumper made from the Maud fabric to a fancy dress dance in Paris: ‘No one in Paris had seen anything quite like it and although Delaunay-Terk was already designing scarves, this was more startling’.32 As historian of art and architecture Nikolaus Pevsner affirmed in 1941, ‘the style called “Teutonic Expressionism’’ or “Paris 1925,” … was in fact created as early as 1913 by the Omega’.33

For Fry and the French painter Henri Matisse, who first met in 1909, the ground-breaking exhibition of Islamic art held in Munich in 1910 inspired new ideas about the valorisation of decorative art, and in particular about the importance of textiles.34 This seminal moment in modern art puts Matisse and Bloomsbury in the same place. In his review of the exhibition, Fry admired Fatimite textiles, drawing attention to fabrics on display made in the tenth to the twelfth centuries, and he enthused over ‘an art in which the smallest piece of pattern-making shows a tense vitality even in its most purely geometrical manifestations’.35 The editor of Fry’s letters, Denys Sutton, has argued that the experience of seeing this exhibition was of ‘major importance in stimulating his conversion to the principles of modern art’ and that ‘Islamic art inevitably heightened his understanding of the vitality of design as something in its own right’.36 Art historian Remi Labrusse has described how a ‘love of fabrics played a leading role in the re-evaluation of the idea of decorative art’ during the late nineteenth century, when there was a ‘growing fascination’ in Europe with textiles of the Muslim Middle East, while in the 1900s, following the example of William Morris, the ‘imitation of Muslim “decorative artists” was encouraged’.37

Exposure to Middle Eastern textiles enabled modern artists to rethink the relationship between painting and the decorative arts in ways that would inform Bell’s experiments in abstraction, mediated by both Fry and Matisse. However, Bell would also have become familiar with fabrics and patterns of this region during her travels in Turkey with Fry in the spring of 1911, when their relationship was especially intimate. They met with a Turkish weaver and shopped for clothing in the bazaar, and Fry brought Bell printed handkerchiefs, shawls and rugs in the Ottoman city of Bursa.38 Reed has drawn attention to the attraction of Omega artists to ‘all things generally Eastern’ and especially to Japanese art, but the impact of Middle Eastern visual culture, particularly on Bell, has not been fully explored.39 If the provocatively vibrant hues and abstract pattern emblematised by Abstract Painting can be partly understood as a form of cultural protest or an antidote to what Bell described as ‘London greyness’, then the model of Middle Eastern art arguably extends her affinity with the sensuous warmth of Mediterranean colour and climate.40 While critics have called attention to Bell’s responsiveness to Matisse, and Reed notes the Matissean aesthetic of Omega products and its similarities to studio props in his 1911–12 interiors, the intersection between Bell, Matisse and Middle Eastern textile design invites closer attention.41

Removed from European disciplines of linear perspective and naturalistic representation, and therefore offering an alternative model of space, Middle Eastern textiles prompted Matisse to explore new ways of organising pictorial space and to experience ‘the metamorphosis of the image into an independent, decorated surface’.42 His family were weavers in the French textile town of Bohain-en-Vermandois and his lifelong interest in and collection of textiles profoundly shaped his visual language. As the 2004 exhibition Matisse: His Art and His Textiles (Royal Academy of Arts, London) showed, his collection or ‘working library’ ranged from eighteenth- and nineteenth-century French textiles to Turkish and Moroccan fabrics and Persian carpets.43 An image of the painter taken by photographer Alvin Langdon Coburn in May 1913 in Matisse’s Paris studio reveals the characteristically fabric-draped environment that Bell would have witnessed when she visited him at Quai Saint-Michel the following year.44 She would already have been familiar with his deployment of textiles in The Red Studio 1911 (Museum of Modern Art, New York), exhibited at the Second Post-Impressionist Exhibition in 1912, which according to Matisse incorporated ‘the warm blacks of the border of a piece of Persian embroidery placed above the chest of drawers’ into the decorative field.45 Matisse’s biographer Hilary Spurling argues that during this pre-war period he employed textiles ‘as subversive agents in the campaign to liberate painting’, while the art historian Jack Flam has noted the painter’s ‘use of abundant, severely flattened decorative motifs’ as a means of ‘animating the space of the “backgrounds” in his painting’.46 These effects are nowhere more evident than in Interior with Aubergines (Intérieur aux Aubergines) 1911 (Musée de Beaux-Arts, Grenoble), where the counter-rhythms of jostling patterns charge the surfaces of the walls, screen and tablecloth, and confuse their borders.

In an essay of 1930 Fry identified Matisse’s reinvention of surface as a gift he shared with ‘almost all Mohommedan art’: finding ‘rich new and surprising harmonies of colour notes placed in apposition upon a flat surface’.47 Like the best of Eastern craftsmen, Fry argued, the painter sought the ‘perfect accord of all the colours’ but also ‘an element of surprise’, which gave ‘extraordinary freshness and vitality to his schemes even viewed as pure decoration, viewed as we might view some rare Persian rug’. Fry articulated a widely held position, one that Labrusse describes as characteristic of ‘an entire generation’ for whom ‘carpets and fabrics, decoration and the Orient were inextricably linked’.48 His description of the Eastern craftsman also echoes the principles he set out for the Omega artisan-artist in 1914: ‘to keep the spontaneous freshness of primitive or peasant work while satisfying the needs and expressing the feelings of the modern cultivated man’.49 The vogue for what was loosely termed ‘primitive’ art meant that Omega products were marketed alongside ‘Asian and North African textiles and ceramics, displays of children’s drawings, reproductions of Byzantine mosaics at Ravenna, and contemporary Italian folk art’.50 By the time Bell was making her abstract work in 1914, she was also designing for the Kevorkian Counter, an art dealer specialising in Near Eastern art.51

Fig.5

Vanessa Bell

A Conversation 1913–16

Courtauld Gallery, London

© 1961 Estate of Vanessa Bell, courtesy Henrietta Garnett

Photo © Courtauld Gallery, London

The musical analogy widely employed in Fry’s formalist discourses on art connects Eastern aesthetics to his own aspirations for non-narrative painting. Arguably, Bell was applying ‘new and surprising harmonies of colour notes’ to a flat surface in her pursuit of pure abstraction decades earlier than Fry’s identification of this quality in Matisse in 1930. Despite the extreme simplification of her designs, she may well have found stimuli in the interlocking patterns and flat or tessellated designs of Middle Eastern fabrics. Moriz Dreger, one of the authors of the 1910 Munich exhibition catalogue with whom Fry would have found consonance, compared the effect of looking at the textiles to the experience of music. In his interpretation, the laws of Islamic art – of ‘infinite relationship’ and ‘absolute surface’ – are exemplified here in their purest form.52

According to Labrusse, Matisse used textiles in a way that responds to these laws by ‘putting pictorial space under tension in two ways: rhythm and folds’.53

In works such as A Conversation 1913–16 (fig.5), Bell too explored the rhythms created by folds in fabrics: her composition is structured by the interplay between the verticals of hanging curtains, the curving lines of the women’s dresses, and the flattened green background which evokes a draped cloth with a floral pattern. While Matisse’s use of decorative motifs typically creates a dynamic surface often radiating beyond the frame, in her Abstract Composition c.1913–14 (private collection) Bell creates surface tension through an optical oscillation between the triplet of red stripes and the two oblongs on the opposite side of the composition, an effect which is

heightened by the stippling in the corners and along the right side.

Fig.6

Vanessa Bell

White 1913

Printed linen

Victoria and Albert Museum, London

© Victoria and Albert Museum

Fig.7

Attributed to Vanessa Bell

Rug design, undated

Gouache and pencil on paper

Courtauld Gallery, London

Photo © The Samuel Courtauld Trust, The Courtauld Gallery, London

Middle Eastern textile design involved compositional processes which arguably encouraged both artists in their steps toward abstraction. Matisse’s use of papier collé in the 1940s has been compared to the appliqué process of sewing an Egyptian khayamiya (curtain): both techniques, art historian Sam Bowker observes, ‘may be described as “drawing with scissors”’.54 Several features relating to Islamic decoration may also be identified in Bell’s abstract painting and design, if indirectly, and can be seen mingling with Byzantine sources: for instance, the repetitive floral and vegetal motifs, including the palm-like pattern in White (fig.6) and the stylised poppy, which appear in several paintings and designs by Bell and Grant of this period. The motif becomes the organising principle in a fire screen designed by Grant with a five-flower pattern of rhythmic curves, which was embroidered in silk by Bell in 1913 (Provost and Scholars of King’s College, Cambridge).55 She is believed to have added the contrastingly geometric border of narrow stripes in alternating colours, in a modification characteristic of her experiments in abstraction.56 Circular and geometric motifs, which are also fundamental in Islamic pattern, were pervasive in the Omega design vocabulary. Alternating blue and white circles appear within a gridded structure on the left hand of an undated rug design attributed to Bell (fig.7), which seems associated with her Abstract Painting in its rich contrasts of red with a central expanse of orange.57 Viewing these works alongside the warm oranges and browns of a sixteenth-century Turkish prayer rug that was exhibited in Munich in 1910 (now in the Kunstgewerbemuseum, Berlin) reinforces the sense of Bell’s affinity with the material and visual culture of this region.58

Fig.8

Saloua Raouda Choucair

Poem Wall 1963–5

White wood

800 x 1645 x 300 mm

Tate T13279

© Saloua Raouda Choucair Foundation

Photo © Tate

This dialogue continued to resonate in the 2014 display of Abstract Painting at Tate Modern, London, when it was paired with the abstract wooden sculpture Poem Wall 1963–5 (fig.8) by Lebanese artist Saloua Raouda Choucair (born 1916).59 Choucair’s work is informed by Islamic aesthetics and the structures and meter of Sufi poetry. Both women pioneers of abstraction, Bell and Choucair reveal an attentiveness to design and pattern: the effects of interlocking geometric forms and the potency of spatial openings, whether through borders of unpainted canvas or the negative space between sculptural blocks. Bell’s Abstract Painting can be seen, then, to participate in an ongoing conversation about abstraction and its relationship to decorative art, which went beyond national and even European boundaries, absorbing as much as it refracted and transformed these diverse cultural sources.