T.E. Hulme, ‘Modern Art – II. A Preface Note and Neo-Realism’

The New Age, 12 February 1914, pp.467–9.

Modern Art. – II.

A Preface Note and Neo-Realism.

By T.E. Hulme.

As in these articles I intend to skip about from one part of my argument to another, as occasion demands, I might perhaps give them a greater appearance of shape by laying down as a preliminary three theses that I want to maintain.

1. There are two kinds of art, geometrical or abstract, and vital and realistic art, which differ absolutely in kind from the other. They are not modifications of one and the same art, but pursue different aims and are created to satisfy a different desire of the mind.

2. Each of these arts springs from, and corresponds to, a certain general attitude towards the world. You get long periods of time in which only one of these arts and its corresponding mental attitude prevails. The naturalistic art of Greece and the Renaissance corresponded to a certain rational humanistic attitude towards the universe, and the geometrical has always gone with a different attitude of greater intensity than this.

3. The re-emergence of geometrical art at the present day may be the precursor of the re-emergence of the corresponding general attitude towards the world, and so of the final break up of the Renaissance.

This is the logical order in which I state the position. Needless to say, I did not arrive at it in that way. I shall try to make a sweeping generalisation like the last a little less empty by putting the matter in an autobiographical form. I start with the conviction that the Renaissance attitude is breaking up and then illustrate it by the change in art, and not vice versa. First came the reaction against the Renaissance philosophy, and the adoption of the attitude which I said went with the geometrical art.

Just at this time I saw Byzantine mosaic for the first time. I was then impressed by these mosaics, not as something exotic or “charming,” but as expressing quite directly an attitude which I to a certain extent agreed with. The important thing about this for me was that I was then, owing to this accidental agreement, able to see a geometrical art, as it were, from the inside. This altered my whole view of such arts. I realised for the first time that their geometrical character is essential to the expression of the intensity they are aiming at. It seemed clear that they differed absolutely from the vital arts because they were pursuing a different intention, and that what we, expecting other qualities from art, look on as dead and lifeless, were the necessary means of expression for this other intention.

Finally I recognised this geometrical re-emerging in modern art. I had here then very crudely all the elements of the position that I stated in my three theses.

At that time, in an essay by Paul Ernst on religious art, I came across a reference to the work of Riegl and Worringer. In the latter particularly I found an extraordinarily clear statement founded on an extensive knowledge of the history of art, of a view very like the one I had tried to formulate. I heard him lecture last year and had an opportunity of talking with him at the Berlin Æsthetic Congress. I varied to a certain extent from my original position under the influence of his vocabulary, and that influence will be seen in some, at any rate, of the articles.

* * *

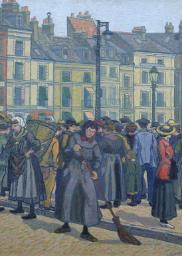

To turn now to Mr. Ginner’s defence of Neo-Realism. His article having somewhat the character of a painter’s apologia, inevitably raises points over the whole range of the subject. I confine myself therefore to the main argument, which, put shortly, is that (1) All good art is realistic. Academism is the result of the adoption by weak painters of the creative artist’s personal method of interpreting nature, and the consequent creation of formulæ, without contact with nature. (2) The new movement in art is merely an academic movement of the kind, springing from the conversion of Cézanne’s mannerisms into formulæ. (3) The only remedy is a return to realism. Only a realistic method can keep art creative and vital.

These statements are based on such an extraordinarily confused and complicated mass of assumptions that I cannot give any proper refutation. I shall just try to show exactly what assumptions are made, and to indicate in a series of notes and assertions an opposite view of art to Mr. Ginner’s. I can only give body to these assertions and prove them much later in the series.

Take first his condemnation of the new movement as academic, being based on the use of formulæ. My reply to this is that the new movement does not use formulæ, but abstractions, quite a different thing. Both are “unlike nature,” but while the one is unlike, owing to a lack of vitality in the art, resulting in dead conventions, the other is unlike, of deliberate intent, and is very far from being dead. Mr. Ginner’s misconception of the whole movement is due to his failure to make this distinction, a failure ultimately arising from the assumption that art must be realistic. He fails to recognise the existence of the abstract geometric art referred to in my prefatory note.

If you will excuse the pedantry of it, I think I can make the matter clearer by using a diagram:

R.........p(r) .........a(r) .........A

I take (R) to represent reality. As one goes from left to right one gets further and further from reality. The first step away being p(r), that is the artist’s interpretation of nature. The next step a(r) being an art using abstractions (a), with a certain representative element (r). The element (a) owes its significance to, and is dependent on the other end (A) of this kind of spectrum – a certain “tendency to abstraction.” I assert that there are two arts, the one focussed round (R), which is moved by a delight in natural forms, and the other springing from the other end, making use of abstractions as a method of expression. I am conscious that this is the weak point of my argument, for I cannot give body to this conception of the “expressive use of abstraction” till later on in the series.

Looking at the matter from this point of view, what is the source of Mr. Ginner’s fallacy? He admits that p(r) the personal interpretation of reality, but as he would deny the possibility of an abstract art altogether, any further step away from reality must appear to him as decay, and the only way he can explain the (a) in a (r) is to look on it as a degeneration of (p) in p(r). An abstraction to him then can only mean that decay of mannerism in formulæ which comes about when the artist has lost contact with nature, and there is no personal first-hand observation. When, therefore, Mr. Ginner says the adoption of formulæ leads to the decay of an art, it is obvious that this must be true if by art you mean realistic art. Inside such art, whose raison d’être is its connection with nature, the use of formulæ, i.e., a lack of personal, creative and sincere observation, must inevitably lead to decay. But here comes the root of the whole fallacy. Realistic art is not the only kind of art. If everything hangs on the (R) side of my diagram then the (a) in a(r) must seem a decayed form of (p) in p(r). But in this other abstract art the (a) in a(r) gets its whole meaning and significance from its dependence on the other end of the scale A, i.e., from its use by a creative artist as a method of expression. Looked at from this point of view, the position of abstraction is quite a different one. The abstractions used in this other art will not bring about a decadence, they are an essential part of its method. Their almost geometrical and non-vital characters is not the result of weakness and lack of vitality in the art. They are not dead conventions, but the product of a creative process just as active as that in any realist art. To give a concrete example of the difference between formula and abstraction. Late Greek art decays into formulæ. But the art before the classical made deliberate use of certain abstractions differing in kind from the formulæ [end of p.467] used in the decadence. They were used with intention, to get a certain kind of intensity. The truth of this view is conveniently illustrated by the history of Greek ornament, where abstract and geometrical forms precede natural forms instead of following them.

To these abstractions, the hard things Mr. Ginner says about formulæ have no application.

We shall never get any clear argument on this subject, then, until you agree to distinguish these two different uses of the word formula. (1) Conventional dead mannerism. (2) Abstraction, equally unlike nature, but used in a creative art as a method of expression.

The first effort of the realists then to give an account of abstraction comes to grief. Abstractions are not formulæ. In their effort to make the matter seem as reasonable as possible the realists have a second way of conceiving the nature of abstractions which is equally misleading. They admit the existence of decorative abstractions. When they have managed to give partial praise to the new movement in this way, they then pass on to condemn it. They assert that the repetition of empty decorative forms must soon come to an end, that pure pattern does not contain within itself the possibility of development of a complete art. But their modified approval and their condemnation are alike erroneous. This second misconception of abstractions as being decorative formulæ, is as mistaken as the first conception of them as being conventionalised mannerisms. Like the first, it springs from a refusal to recognise the existence of an art based on the creative use of abstraction, an art focussed on the right hand side (A) of my diagram. As long as that is denied, then abstractions must inevitably be either conventionalised mannerisms or decorative. They are neither.

Now to apply the first distinction between formulæ and abstraction to Mr. Ginner’s argument about the new movement in art. This art undoubtedly uses abstraction. Are these abstractions formulæ in his sense of the word or not? If they are, then his argument is valid and we are in presence of a new academic movement.

I deny, however, that the abstractions to be found in the new art are dead formulæ. For the moment, I do not intend to offer any proof of this assertion, as far as

Cubist art itself is concerned. I intend to deal rather with the precursor of the movement, that is Cézanne himself. The point at issue here then is narrowed down to this. The Cubists claim that the beginnings of an abstract art can be found in Cézanne. Mr. Ginner, on the contrary, asserts that Cézanne was a pure realist. It is to be noticed that even if he proved his case, he would not have attacked the new art itself, but only its claimed descent from Cézanne.

One must be careful not to treat Cézanne as if he actually were a Cubist; he obviously is not. One must not read the whole of the later movement into him. But there are in his paintings elements which quite naturally develop into Cubism later. You get, as contrasted with the Impressionists, a certain simplification of places, an emphasis on three-dimensional form, giving to some of his landscapes what might be called a Cubist appearance. It is true that this simplification and abstraction, this seeing of things in simple forms, as a rule only extends to details. It might be said that simplifications are, as it were, “accepted” passively, and are not deliberately built up into a definite organisation and structure.

The first thing to be noticed is that even supposing that Cézanne’s intentions were entirely realistic, he initiated a break-up of realism and provided the material for an abstract art. Picasso came along and took over these elements isolated by Cézanne, and organised them. If the simplifications in Cézanne had passed beyond details and become more comprehensive, they would probably of themselves have forced him to build up definite structures.

But not only are the elements of an abstract art present in Cézanne, I should say also that there was an embryo of the creative activity which was later to organise these elements.

I put again the opposed view to this. I have already said that the simplification of planes is based on that actually suggested by nature. The realist intention, it might be said, is directed towards weight and three-dimensional form, rather than towards light, yet it still remains realist. This is quite a conceivable view. It is quite possible that a realist of this kind might prepare the material of an abstract art automatically. The abstractions might be produced accidentally, with no attempt to use them creatively as means of expression.

It seems to me, however, that there are many reasons against the supposition that this was the case with Cézanne. In looking for any traces of this abstract organising tendency, one must remember that Cézanne was extraordinarily hampered by the realism of his period; in some ways he might be said to have carried out the complete impressionist programme. Yet showing through this you do get traces of an opposed tendency. I should base this assertion on two grounds:

(1) Though the simplification of planes may appear passive and prosaic, entirely dictated by a desire to reproduce a certain solidity, and from one point of view almost fumbling, yet at the same time one may say that in this treatment of detail, there is an energy at work which, though perhaps unconscious, is none the less an energy which is working towards abstraction and towards a feeling for structure. If one thinks of the details, rather than of the picture as a whole, one need not even say this energy is unconscious. In this respect Cézanne does seem to have been fairly conscious, and to have recognised what he was after better than the contemporary opinion which looked upon him as an impressionist. I should say that expressions like “everything is spherical or cylindrical,” and all the forms of nature “peuvent se ramener au cône, au cylindre et a la sphere,” yet show the working of a creative invention, which had to that extent turned away from realism and showed a tendency towards abstraction. (It is obvious that these words were not used in the sense in which a Cubist might use them; they apply to details rather than to wholes. Yet a denial of the wider application does not, as many people seem to suppose, justify the idea that they were meant in the sense in which a Cubist might understand them.) These sentences seem to me to destroy the whole of Mr. Ginner’s argument, unless, of course, you go a step further than those who explain Cézanne’s painting as the result of astigmatism and incompetence, and assert that the poor man could not even use his mother tongue. The simplification of planes itself, then, does seem to show a tendency to abstraction which is working itself free. (2) But the fact that this simplification is not entirely realistic and does come from a certain feeling after structure, seems to me to be demonstrated in a more positive way by pictures like the well-known “Bathing Women.” Here you get a use of distortion and an emphasis on form which is constructive. The pyramidal shape, moreover, cannot be compared to decoration, or to the composition found in the old masters. The shape is so hard, so geometrical in character, that it almost lifts the picture out of the realistic art which has lasted from the Renaissance to now, and into the sphere of geometric art. It is in reality much nearer to the kind of geometrical organisations employed in the new art.

That is a theoretical statement of the errors Mr. Ginner makes. I think it might be worth while to go behind these errors themselves, to explain the prejudices which are responsible for their survival.

As a key to his psychology, take the sentence which he most frequently repeats. “It is only this intimate relation between the artist and the object which can produce original and great works. Away from nature, we fall into unoriginal and monotonous formulæ.” In repeating this he probably has at the back of his mind two quite different ideas, (1) the idea that it is the business of the artist to represent and interpret nature, and (2) the assumption that even if it is not his duty to [end of p.468] represent nature that he must do so practically, for away from nature the artist’s invention at once decays. He apparently thinks of an artist using abstractions as of a child playing with a box of tricks. The number of interesting combinations must soon be exhausted.

The first error springs from a kind of Rousseauism which is probably much too deeply imbedded in Mr. Ginner’s mind for me to be able to eradicate. I merely meet it by the contrary assertion that I do not think it is the artist’s only business to reproduce and interpret Nature, “source of all good,” but that it is possible that the artist may be creative. This distinction is obscured in Mr. Ginner’s mind by the highly coloured and almost ethical language in which he puts it. We are exhorted to stick to Mother Nature. Artists who attempt to do something other than this are accused of “shrinking from life.” This state of mind can be most clearly seen in the use of the word simplification. There is a confusion here between the validity and origin of simplification. The validity of simplification is held to depend on its origin. If the simplification, such as that for example you get in Cézanne’s treatment of trees, is derived from Nature and comes about as the result of an aim which is itself directed back to Nature, then it is held to be valid. I, on the other hand, should assert that the validity of the simplification lay in itself and in the use made of it and had nothing whatever to do with its descent, on its occupying a place in Nature’s “Burke.”

Take now the second prejudice – the idea that whatever he may do theoretically, at any rate practically, the artist must keep in continual contact with Nature – “The individual relying on his imagination and his formula finds himself very limited, in comparison with the infinite variety of life. Brain ceases to act as it ceases to search out expression of Nature, its only true and healthy source.”

You see here again the ethical view of the matter – the idea of retribution. Get further and further away from dear old Mother Nature and see what happens to you: you fall into dead formulæ.

My answer to this argument is: that while I admit it to be to a certain extent true, I deny the conclusion Mr. Ginner draws from it.

I admit that the artist cannot work without contact with, and continual research into nature, but one must make a distinction between this and the conclusion drawn from it that the work of art itself must be an interpretation of nature. The artist obviously cannot spin things out of his head, he cannot work from imagination in that sense. The whole thing springs from misconception of the nature of artistic imagination. Two statements are confused: (1) that the source of imagination must be nature, and (2) the consequence illegitimately drawn from this, that the resulting work must be realistic, and based on natural forms. One can give an analogy in ordinary thought. The reasoning activity is quite different in character from any succession of images drawn from the senses, but yet thought itself would be impossible without this sensual stimulus.

There must be just as much contact with nature in an abstract art as in a realistic one; without that stimulus the artist could produce nothing. In Picasso, for example, there is much greater research into nature, as far as the relation of planes is concerned, than in any realist painting; he has isolated and emphasised relations previously not emphasised. All art may be said to be realism, then, in that it extracts from nature facts which have not been observed before. But in as far as the artist is creative, he is not bound down by the accidental relations of the elements actually found in nature, but extracts, distorts, and utilises them as a means of expression, and not as a means of interpreting nature.

It is true, then, that an artist can only keep his work alive by research into nature, but that does not prove that realism is the only legitimate form of art.

Both realism and abstraction, then, can only be engendered out of nature, but while the first’s only idea of living seems to be that of hanging on to its progenitor, the second cuts its umbilical cord.

How to cite

T.E. Hulme, ‘Modern Art – II. A Preface Note and Neo-Realism’, in The New Age, 12 February 1914, pp.467–9, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://www