James Bolivar Manson 1879–1945

James Bolivar Manson 1879–1945

Self-Portrait c.1912

Oil paint on canvas

support: 508 x 397 mm

Tate N04929

Presented by D.C. Fincham 1938

© Tate

Fig.1

James Bolivar Manson

Self-Portrait c.1912

Tate N04929

© Tate

James Bolivar Manson was born on 26 June 1879 at 65 Appach Road, Brixton, in south London, the eldest son of four brothers and two sisters. His mother was Margaret Emily Manson (née Deering) and his father was James Alexander Manson, a poet and freelance writer. Manson attended Alleyn’s School in Dulwich, leaving at the age of sixteen to begin work as an office boy for the publisher George Newnes. He studied art in his spare time at first Heatherly’s and later Lambeth Schools of Art, but begrudgingly secured work as a bank clerk at the behest of his father, who desired that his son pursue a more stable career than that of a professional artist.

In 1903 Manson married the musician Lilian Laugher (fig.2). Lilian had stayed with Manson’s parents in Dulwich upon her return from Berlin, where she had trained as a violinist. It is unclear from the available accounts what Lilian’s connection to the Mansons was or whether James and Lilian were acquainted prior to this. With the extra funds saved from Lilian’s work as a music teacher at the James Allen’s Girls School in Dulwich, Manson was able to quit his post at the bank and shortly after they were married the pair moved to Paris.

James Bolivar Manson and Lilian Manson in the Grounds of Western House, Rye, Sussex August 1913

Photograph, black and white, on paper (photographer unknown)

Tate Archive TGA 792/21

Fig.2

James Bolivar Manson and Lilian Manson in the Grounds of Western House, Rye, Sussex August 1913

Tate Archive TGA 792/21

Charles Polowetski, Bernard Gussow, James Bolivar Manson and Samuel Halpert in a Studio on Rue Belloni, Paris 7 June 1903

Photograph, black and white, on paper, taken by Charles Ezekiel Polowetski (born 1884)

Inscribed in an unknown hand 'Halpert did a Beardsley portrait of [?"him" or "me"]', 'In Jacob Epstein's Studio | rue Belloni, Paris', 'Charles | Polowetski', 'June 7 1903', 'Bernard | Gussow', 'J B Manson', 'Samuel Halpert' and annotations for printing in pencil on back

Tate Archive TGA 792/17

Fig.3

Charles Polowetski, Bernard Gussow, James Bolivar Manson and Samuel Halpert in a Studio on Rue Belloni, Paris 7 June 1903

Tate Archive TGA 792/17

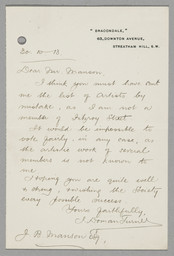

In Paris, Manson began full-time study at the famous Académie Julian, where Pierre Bonnard and Edouard Vuillard had trained, as well as fellow Fitzroy Street and Camden Town associates Robert Bevan and Stanislawa de Karlowska in the 1890s. Manson shared a rented studio space with the artists Charles Polowetski, Bernard Gussow and Jacob Epstein (fig.3).2 The impressionist painter Manson developed an unlikely friendship with the more radical sculptor Epstein, the pair exchanging many letters in the coming years (fig.4). In 1935 Manson was one of nine signatories, including Kenneth Clark and William Rothenstein, of a letter to the Times in protest against the proposed removal of Epstein’s sculptures from the British Medical Association building on the Strand (fig.5).3

Jacob Epstein 1880–1959

Letter to James Bolivar Manson 5 April 1911

Tate Archive TGA 806/1/300

© The estate of Sir Jacob Epstein

Fig.4

Jacob Epstein

Letter to James Bolivar Manson 5 April 1911

Tate Archive TGA 806/1/300

© The estate of Sir Jacob Epstein

Jacob Epstein 1880–1959

Letter to James Bolivar Manson 5 May 1940

Tate Archive TGA 806/1/304

© The estate of Sir Jacob Epstein

Fig.5

Jacob Epstein

Letter to James Bolivar Manson 5 May 1940

Tate Archive TGA 806/1/304

© The estate of Sir Jacob Epstein

James and Lilian returned to London in 1904, where their first child Mary was born. A second daughter, Jean, arrived in 1906. 184 Adelaide Road in Hampstead was their first, modest family home; Manson kept a studio space to the rear of the house. The family was short of money at this time, with Manson attempting to carve out a career as a full-time artist and Lilian teaching music in the front room for extra income.

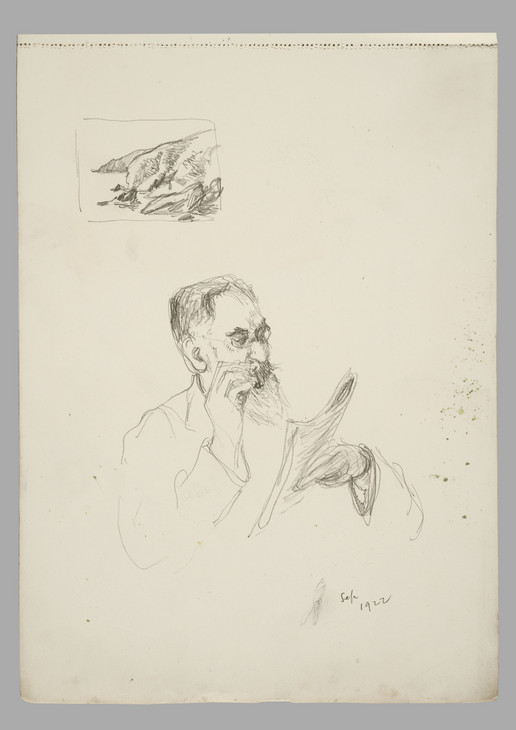

James Bolivar Manson 1879–1945

Lucien Pissarro Reading in Dartmouth, Devon September 1922

Graphite on sketchbook paper

255 x 180 mm

Inscribed by the artist 'Sep 1922' in pencil bottom right

Tate Archive TGA 806/4/1

© Estate of James Bolivar Manson

Fig.6

James Bolivar Manson

Lucien Pissarro Reading in Dartmouth, Devon September 1922

Tate Archive TGA 806/4/1

© Estate of James Bolivar Manson

The first recorded correspondence between Manson and Pissarro is dated 30 November 1910, when Lucien writes: ‘I shall try to be at Fitzroy Street by 2.30 on Saturday ... I have a key. We shall be able to go and talk quietly in the studio.’8 Manson was hoping to view works by Pissarro as research for an article he was preparing on the older artist.9 Manson wrote many articles during this period as a means of supplementing his income. Throughout his lifetime and alongside the duties of his official posts, he contributed to a wide variety of art periodicals including Apollo, Burlington Magazine, Creative Art and Gazette des Beaux-Arts, as well as for the popular press in the Daily Herald and Outlook magazine. He avidly continued to highlight Pissarro’s artistic achievements in print and to promote his work in public, perhaps to the detriment of his own career as a practising artist.10

Manson’s visit to the Fitzroy Street studio in 1910 marked his introduction to the wider Fitzroy Street Group. Although he may have had to wait around six months before becoming a full member, he probably accompanied Pissarro in attending their meetings and ‘At Homes’ from that point on.11 Perhaps spurred on by discussions at Fitzroy Street, Manson could be counted among those more adventurously minded artists of the group who felt the need for some new form of exhibiting society in opposition to the conservatism of the New English Art Club. In his 1913 introduction to the Exhibition of the Work of English Post-Impressionists, Cubists and Others, Manson expressed his opinion that the NEAC in 1910 ‘had already found its respectable level; it had reached a point of safety. It was too tired or too wise to venture further.’12 He did have works accepted by the NEAC in 1909, but when the chance arose in 1911 Manson enthusiastically took up his role as both contributing member and secretary of the Camden Town Group. He was probably granted the role of secretary owing to his dual experience as both writer and as banker, and therefore competent with accounts. Clearly suited to the task, he would later reprise this secretarial role at the formation of the London Group in 1914.

James Bolivar Manson 1879–1945

Michaelmas Daisies c.1923

Oil paint on canvas

support: 610 x 508 mm

Tate N01355

Presented by subscribers 1923

© Tate

Fig.7

James Bolivar Manson

Michaelmas Daisies c.1923

Tate N01355

© Tate

Charles Ginner, in his 1945 recollections of the Camden Town Group, seems to strengthen the view that Pissarro and Manson held a somewhat tangential artistic outlook to the rest of the group:

Lucien Pissarro worshipping his father Camille and coming out with his recurring sentence un peu plus de variétés to impress us with the importance of a full orchestration of colour; [and] J.B. Manson fighting Pissarro’s battles.16

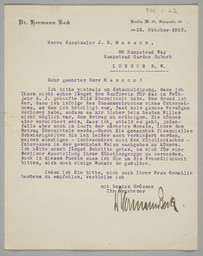

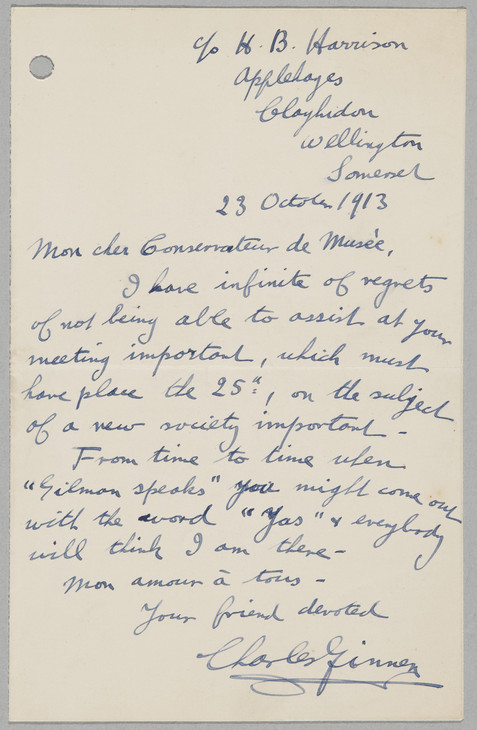

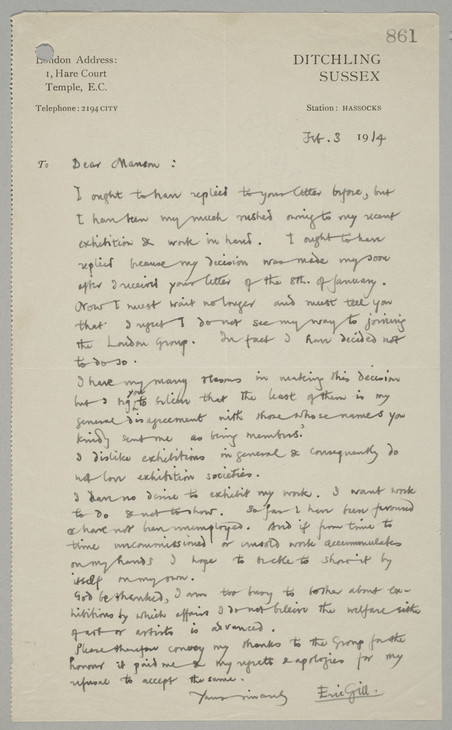

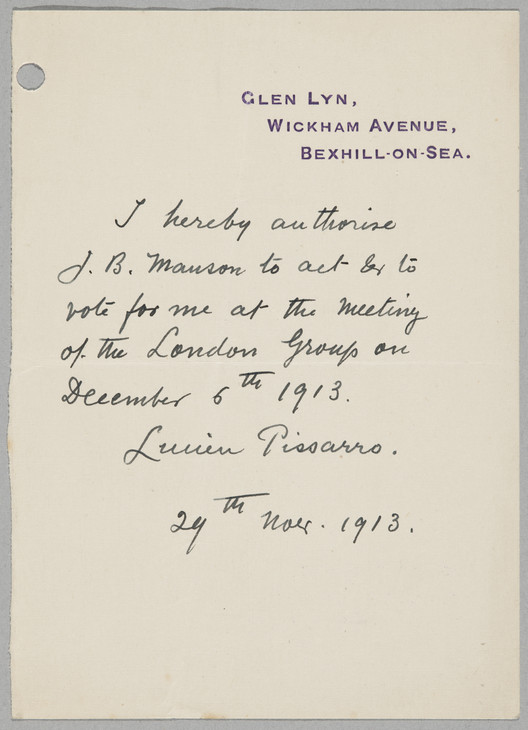

Ginner’s comments, though, do not acknowledge Manson’s significant role as mediator between the members’ differing ideals, performed while secretary of both the Camden Town Group and in the early days of the London Group. Manson would often act as proxy for non-attending members in meetings and was charged with undertaking much of the groups’ general correspondence (see, for example, figs.8 and 9).

Charles Ginner 1878–1952

Letter to James Bolivar Manson 23 October 1913

Tate Archive TGA 806/10/6

© Estate of Charles Ginner

Fig.8

Charles Ginner

Letter to James Bolivar Manson 23 October 1913

Tate Archive TGA 806/10/6

© Estate of Charles Ginner

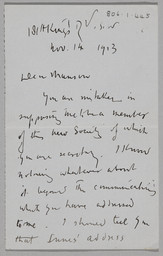

Eric Gill 1882–1940

Letter to James Bolivar Manson 3 February 1914

Tate Archive TGA 806/10/6

Fig.9

Eric Gill

Letter to James Bolivar Manson 3 February 1914

Tate Archive TGA 806/10/6

Manson’s obligations as secretary certainly impacted on the time available for painting. His artistic ambitions were further curtailed when, in 1912, at the insistence of Lilian, he took up work as an assistant at the Tate Gallery, earning £150 per year, in order to ensure the health of the family finances. The then director of the Tate, Charles Aitken, had made a personal request to the trustees that a post be offered to Manson after the artist had aided him in the hanging of an exhibition. Aitken’s personal respect for Manson evidently translated into a respect for his opinions on art, with Manson successfully able to encourage the Tate Gallery’s acceptance of work by Camden Town Group artists, including that of Walter Sickert, as early as 1915.17

At the formation of the London Group, Manson seemed initially excited by the potential the larger grouping offered for wider public awareness of modern art and further subversion of the rigid academic art strictures. For the transitional exhibition English Post-Impressionists, Cubists and Others in 1913, Manson explained the aims of the artists housed in the first two of three rooms. With a tone of great optimism he wrote of the newly formed London Group:

More eclectic in its constitution, it will no longer limit itself to the cultivation of one single school of thought, but will offer hospitality to all manner of artistic expression provided it has the quality of sincere personal conviction. The Group promises to become one of the most influential and most significant art movements in England.

To conceive a limit to artistic development is an admission of one’s own limitations. Nothing is finally right in art; the rightness is purely personal, and for the artist himself. So, in the London Group, which is to be the latest development of the original Fitzroy Street Group, all modern methods may find a home. Cubism meets Impressionism, Futurism and Sickertism join hands and are not ashamed, the motto of the Group being that sincerity of conviction has a right of expression.18

To conceive a limit to artistic development is an admission of one’s own limitations. Nothing is finally right in art; the rightness is purely personal, and for the artist himself. So, in the London Group, which is to be the latest development of the original Fitzroy Street Group, all modern methods may find a home. Cubism meets Impressionism, Futurism and Sickertism join hands and are not ashamed, the motto of the Group being that sincerity of conviction has a right of expression.18

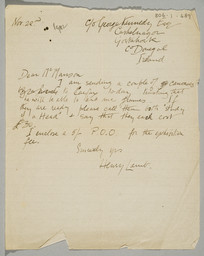

Lucien Pissarro 1863–1944

Letter to James Bolivar Manson 29 November 1913

Tate Archive TGA 806/10/6

© Estate of Lucien Pissarro

Fig.10

Lucien Pissarro

Letter to James Bolivar Manson 29 November 1913

Tate Archive TGA 806/10/6

© Estate of Lucien Pissarro

I feel that by denying these new movements a right to express themselves, we should be acting exactly as the Academicians did with regard to the Impressionists and precisely as the N.E.A.C. does when it says with regard to Fitzroy St: ‘You may be alright from your own point of view but we shant show yr. work.’

I have no sympathy with that attitude and I do not want to support it, so I think I shall stay with the ‘London Group’.

I feel the other attitude of intoleration is rather narrow.

I don’t think we have any reason to be afraid of a few extreme young men; nor ought we to run away from them.21

I have no sympathy with that attitude and I do not want to support it, so I think I shall stay with the ‘London Group’.

I feel the other attitude of intoleration is rather narrow.

I don’t think we have any reason to be afraid of a few extreme young men; nor ought we to run away from them.21

Pissarro’s disillusion was evidently too great and he resigned by letter from both the Fitzroy Street and London Group in March 1914, on the cusp of the first official exhibition of the latter.22 Manson exhibited works in the London Group show, but perhaps anxious now that he lacked a true artistic ally within the group, he, too, resigned at the end of March. Although privately exhorting moderation and understanding of the group’s younger factions, in his review of the exhibition in Outlook, Manson went on the offensive, dismissing the cubo-futurists such as David Bomberg and Wyndham Lewis as mere ‘notoriety-mongers’, whose abstract compositions might only ‘serve a useful purpose as a design for a pavement or for a linoleum in the house of some fin-de-siècle countess’.23 In the difference between this review and his earlier rhetoric of inclusiveness, one gets a sense of the sometimes contradictory nature of his opinions that would later characterise his directorship of the Tate Gallery.

Manson held hopes of enlisting to fight at the start of the First World War, but was prevented on grounds of ill health. Instead, he continued to fulfil his duties as a civil servant at the Tate Gallery and was promoted to the position of Assistant Keeper in 1917.

In December 1919, following Pissarro’s summer meeting with the elderly Claude Monet in Giverny, Manson and Pissarro formed a new society representing the logical conclusion of their impressionist ideals. The Monarro Group – its name an elision of the surnames of the two artists considered of the greatest importance to the members, Monet and Camille Pissarro – held its first exhibition in February 1920 at the Goupil Gallery. Manson, once more both member and secretary, exhibited nine works in total, and alongside more illustrious names such as Paul Signac, Pierre Bonnard, Camille Pissarro and Monet, was complimented in reviews for his ‘delicate’ version of impressionism. The reviewer from the Times stated that the show was ‘valuable as a reminder that Impressionism has not said yet all that it has to say, that it can still be practised freshly and with conviction’.24 The Monarro Group held one more exhibition in March 1921, in which a more varied selection of artistic styles was presented, but with Manson’s time increasingly taken up by his work at the Tate and his writings, the group did not last beyond that year.

Despite the diminution of time available for painting, Manson still managed to stage several substantial solo exhibitions during the 1920s in London, Glasgow, Birmingham and Paris. Much of the work comprised the flower paintings by which he made his name throughout the decade. Although he had painted several finely observed still lifes including flowers around the time of the Camden Town Group,25 it was in the 1920s that Manson settled on this particular subject as that best suited to his talents and aims in painting. In a newspaper interview in 1930, he recalled:

I was living in Muirhead Bone’s house in Hampshire during a very wet holiday and as I could not get out, I painted flowers indoors. These works proved to be my best.26

The critic Charles Marriott wrote in the foreword to Manson’s 1925 exhibition:

Of all pictures, the kind of pictures painted by J.B. Manson should stand least in need of introduction, because they are addressed directly to enjoyment. Thought has gone into their making, but they are as independent of thinking for their appreciation as is music or something good to eat.27

The decade also saw the publication of Manson’s first full-length books. He wrote a popular guide to the Tate collection, Hours in the Tate Gallery, with a chapter on ‘New English Art’ in which he praised the work of Philip Wilson Steer, Walter Sickert, Gwen and Augustus John, and Duncan Grant.28 The artist biographies, The Life and Works of Edgar Degas and The Work of John Singer Sargent, were both published in 1927, alongside a prolific output of articles and catalogue introductions for exhibitions such as that of his one-time Camden Town Group compatriot Spencer Gore, in 1928.29

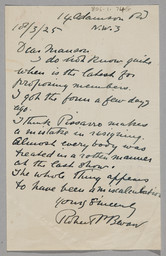

Manson succeeded Charles Aitken to the directorship of the Tate Gallery in August 1930. It has been said that he was the least successful of the directors, with commentators pointing to the conservatism of the gallery’s exhibitions and acquisitions during the 1930s, at a time when it should have been competing with the expanding modern collections of European and American galleries.30 Manson’s personal opinions on the value and successes of certain art forms clearly played a part in Tate passing the chance to buy works by Henry Moore in 1933 and Henri Matisse in 1935, and in its accepting gifts of works by Roger Fry and a loan of works by Francis Picabia in 1935.31 However, there were important acquisitions during Manson’s directorship, including the Stoop Bequest which brought seventeen pieces to the Tate Gallery, including the collection’s first examples of work by Matisse, Paul Cézanne and Georges Braque. It may have been Manson’s flattering 1929 article ‘Mr. Frank Stoop’s Modern Pictures’ in Apollo that helped to confirm the Tate as the logical destination for the bequest.32 Manson did much to improve the gallery during his directorship, for example pushing through the change of name from ‘National Gallery, Millbank’ to the more recognisable ‘Tate Gallery’, approving and overseeing the installation of electric lighting throughout the galleries which allowed for later opening hours, and continuing the planning for the Duveen sculpture galleries begun under Aitken.

The final years of Manson’s directorship were increasingly troubled, as he struggled to balance the pressures of his working life and suffered from rapidly deteriorating health and an increasing dependence on alcohol. In 1937 he was embroiled in a libel action by the artist Maurice Utrillo (1883–1955), following the publication of a Tate Gallery catalogue which incorrectly claimed the artist had died ‘as a result of circumstances which brought social discredit on him’.33 The case was not resolved until the following year, which was to be Manson’s final as director. The incident which ultimately led to his exit, however, happened during celebrations to mark the opening of the British Exhibition at the Louvre in Paris, on 4 March 1938. A drunken Manson in a characteristically mischievous mood interrupted the official speeches with shouts and ‘cock-a-doodle-doos’ and insulted several high-profile guests.34 Upon his return to England, he was forced to resign from his post on grounds of ill health. He received a reasonable pension for his time as a civil servant as well as a wooden paint box as a retirement gift, his colleagues certain of how he would fill his increased free time.35

In the same year Manson moved out of his Hampstead home and separated from Lilian. He would eventually settle in Boltons Studios in South Kensington, taking up residence with Elizabeth Hayward, who changed her name to Manson by deed poll in 1941.36 Pissarro died on 10 July 1944 and almost a year later Manson passed away on 3 July 1945. His obituary in the Times described him as ‘a genial, rather burly man with twinkling eyes, and, in later life, a shock of white hair, [who] was popular both among artists and visitors to the Tate gallery. He was an exceedingly amusing talker, shrewd and sometimes irreverent to the orthodoxies.’37 Memorial exhibitions were held in 1946 at the Wildenstein Galleries in London and the Ferens Art Gallery in Hull and in 1947 at the Victoria Art Gallery in Bath.38

Notes

Another self-portrait was painted in c.1911, Self-Portrait. The Fitzroy Street Studio (Fine Art Society). Reproduced in Camden Town Recalled, exhibition catalogue, Fine Art Society, London 1976 (102).

His friend Samuel Halpert depicted Manson in 1903, NPG 5731, reproduced at National Portrait Gallery, London, http://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/largerimage.php?search=sp&sText=halpert+manson&firstRun=true&rNo=0 , accessed 21 February 2011.

See Wendy Baron, Perfect Moderns: A History of the Camden Town Group, Aldershot and Vermont 2000, p.33, and The Painters of Camden Town, 1905–1920, exhibition catalogue, Christie’s, London 1988, pp.50, 65.

Lucien Pissarro, letter to J.B. Manson, 20 April 1912; quoted in W.S. Meadmore, Lucien Pissarro: Un Coeur simple, London 1962, p.136.

Lucien Pissarro, letter to J.B. Manson, 30 November 1910; quoted in Malcolm Easton, ‘Lucien Pissarro and His Friends at Rye, 1913: A Group of Post-Impressionists on Holiday’, Gazette des Beaux-Arts, November 1968, p.238.

J.B. Manson, ‘Introduction. Rooms I–II’, in Exhibition of the Work of English Post-Impressionists, Cubists and Others, exhibition catalogue, Brighton Public Art Galleries 1913, p.5.

See, for example, Still Life: Tulips in a Blue Jug c.1912, Government Art Collection, London, http://www.gac.culture.gov.uk/work.aspx?obj=13064 , accessed 24 January 2011.

Charles Marriott, ‘Foreword’, in Pictures by J.B. Manson, exhibition catalogue, Ruskin Galleries, Birmingham 1925.

See ‘Archive Journeys: Tate History. Directors: J.B. Manson’, Tate Online, http://www.tate.org.uk/archivejourneys/historyhtml/people_dir_manson.htm , accessed 24 January 2011, and Spalding 1998, pp.62–70.

J.B. Manson, ‘Mr. Frank Stoop’s Modern Pictures’, Apollo, vol.10, no.57, September 1929, pp.127–33. See also Dennis Farr, ‘J.B. Manson and the Stoop Bequest’, Burlington Magazine, vol.125, no.968, November 1983, pp 689–90, for a discussion warning against swift accusations of conservatism directed at Manson’s Tate Gallery directorship.

‘King’s Bench Division Libel Action by a French Painter Settled, Utrillo v. Manson and Others’, Times, 18 February 1938, p.4.

R.R. Tatlock, ‘Foreword’, in J.B. Manson, 1879–1945, exhibition catalogue, Wildenstein & Co., London 1946.

J.B. Manson 1879–1945, Wildenstein & Co., London, 20 March–13 April 1946. Memorial Exhibition of Paintings and Drawings by J.B. Manson, Ferens Art Gallery, Hull, 10 August–5 September 1946. Memorial Exhibition of Paintings and Drawings by J.B. Manson, Victoria Art Gallery, Bath, 22 March–19 April 1947.

Catalogue entries

How to cite

Tom Furness, ‘James Bolivar Manson 1879–1945’, artist biography, January 2011, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://www