The Carfax Gallery and the Camden Town Group

Samuel Shaw

The three Camden Town Group exhibitions were held in the Carfax Gallery in the St James’s area of central London. Samuel Shaw considers the qualities that made the gallery a suitable venue for the group’s exhibitions.

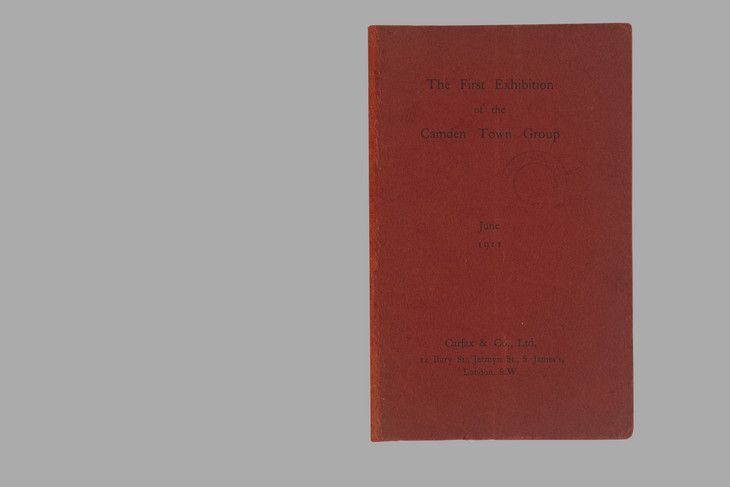

In the second story of his Seven Men (1919), Max Beerbohm (1872–1956) introduces us to two young novelists from very different backgrounds whose careers have converged under strange circumstances. The ‘very rugged and gruff’ Stephen Braxton comes from Far Oakridge, a village in Gloucestershire, and his ‘pleasant little’ counterpart, Hilary Maltby, from under a ‘comfortable roof at Twickenham’, having since ‘taken rooms at Ryder Street’.1 Two of these locations have personal resonances that provide an explicit link to Beerbohm’s close friend, the artist William Rothenstein (1872–1945), who had already appeared as himself in the opening story of the same collection. Far Oakridge was the village to which Rothenstein, tired of London, decamped in 1912. Number 17 Ryder Street, meanwhile, was the central London site of a gallery he had co-founded back in 1899. This gallery was the cosmopolitan Carfax, which, following its move round the corner to 24 Bury Street in March 1905, was the home of all three Camden Town Group exhibitions (fig.1). Beerbohm also exhibited there several times – and doubtless knew the area well.2 It may seem like a minor detail, but in choosing Ryder Street as the home for his character, Maltby, Beerbohm was indirectly telling us something about the Carfax Gallery; something which, as we will see, casts small but important light on the history of the Camden Town Group.

The words ‘Carfax Gallery’ or ‘Carfax & Co.’ will be familiar to anyone who has written on or read about the Camden Town Group. But what do they mean to us? The locations of galleries are not interchangeable: galleries operate in a variety of ways, depending on their size, clientele, commercial strategies and associated artists. Understanding the precise conditions in which an exhibition took place gives us a deeper sense of the meanings an artwork may have conveyed to a contemporary audience. The Carfax should be more than a backdrop to the Camden Town Group exhibitions; knowledge of its operations should expand our understanding of these events.

A few details of the gallery’s set-up are usually provided in historical accounts; most often a variation of Rothenstein’s own description as found in his memoirs, supplemented by a handful of additional facts and figures.3 The gallery was established in 1899 by Rothenstein and John Fothergill (1876–1957) as ‘a centre for work of a certain character’.4 The foundations of the firm were, however, a little shaky; neither Rothenstein nor Fothergill had experience as gallery directors, and did not quite agree on the nature of this ‘certain character’ or how to go about selling it.5 This, coupled with Rothenstein’s fears as to how acting as a gallery adviser would affect his personal relationships with fellow artists (and his already busy schedule), led to a relatively amicable transfer of management in 1901 to Robbie Ross (1869–1918).6 Ross stayed with the firm until 1908, then passing sole control to Arthur Clifton (1863–1932), a trained solicitor and once the gallery’s financial adviser. Though the gallery was not indisposed either to past masters (it held exhibitions of William Blake in 1904 and 1906) or popular contemporaries such as John Singer Sargent (who exhibited there in 1903, 1905 and 1908), its early reputation appears to have rested on its more forward-looking tastes.7 These included exhibitions by Auguste Rodin (1900), Charles Conder (1899, 1900, 1901 and 1902) and Augustus John (1899, 1903 and 1907), before Clifton’s tastes turned to the art of Walter Sickert and his group, who dominated its exhibitions into the early 1920s: the decade that saw the gallery’s eventual demise.8

Contemporary exhibitors at Carfax were usually members of the New English Art Club; and, in its early years at least, the gallery was loosely associated with various writers whose work appeared in the Saturday Review, including Beerbohm, George Bernard Shaw (1856–1950), Robert Cunninghame-Graham (1852–1936) and the art critic D.S. MacColl (1859–1948) who could usually be relied upon to treat its exhibitions kindly.9 In both its Ryder and Bury Street manifestations the Carfax was securely located among the smaller commercial galleries of the time and set a precedent for later enterprises, most obviously the Chenil Gallery in Chelsea (founded in 1905) and the larger Leicester Galleries in Leicester Square (founded in 1902).10

Although much more could be said about these early years – the slightly chaotic beginnings under Rothenstein and Fothergill, and the more prosperous Robbie Ross period – the focus here is on the gallery’s reputation around 1911, the time of the first Camden Town Group exhibition.11 By far the best source on the Carfax in this period is an account left by the artist Paul Nash (1889–1946), which describes the circumstances surrounding his debut solo show in 1912. The fact that Nash, still fresh from the Slade, was shown there is typical of the gallery, which had from the start a reputation for juggling Old Master exhibitions with those of young, relatively unknown artists.

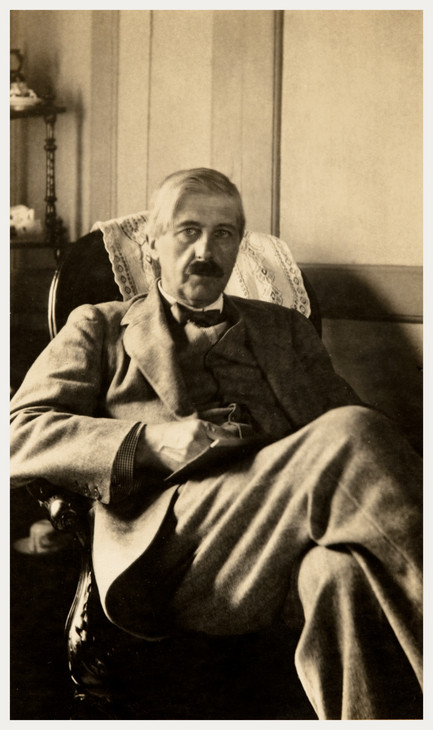

Portrait of Arthur Clifton Early 1900s

Photograph, black and white, on paper (photographer unknown)

Tate Archive TGA 8721/19

Fig.2

Portrait of Arthur Clifton Early 1900s

Tate Archive TGA 8721/19

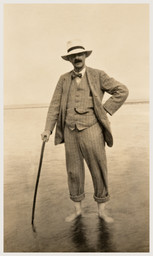

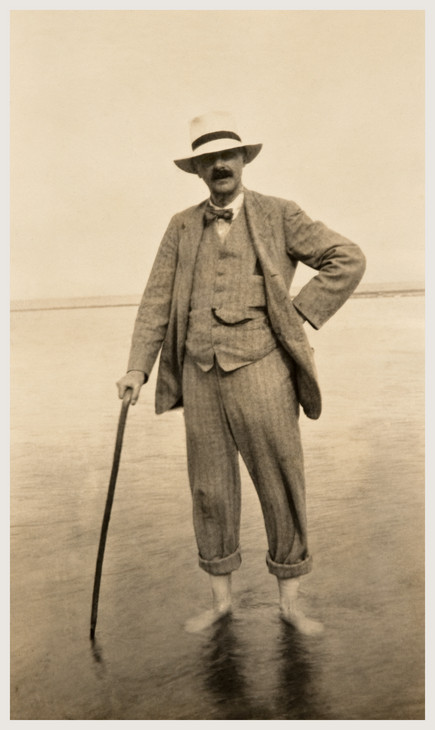

Arthur Clifton Standing in the Sea Early 1900s

Photograph, black and white, on paper (photographer unknown)

Tate Archive TGA 8721/20

Fig.3

Arthur Clifton Standing in the Sea Early 1900s

Tate Archive TGA 8721/20

Although he is, perhaps, exaggerating when he recalls that ‘the Carfax was probably the most distinguished and exclusive gallery in London at this time’, Nash nonetheless leaves us with an interesting account of the space – and of Arthur Clifton (figs.2 and 3).12 He began by describing Bury Street as ‘one of those expensive, rather secret streets running between Piccadilly and St James’s’ – a fact confirmed by Charles Booth’s 1902 survey Life and Labour of the People in London, which categorises the street (and, indeed, the district) as securely ‘well-to-do’: not surprising for St James’s, an area otherwise populated by fashionable clubs, high-priced residences and galleries of a rather less forward-looking character.13

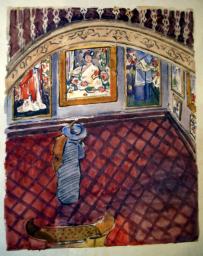

Nash goes on to detail the gallery’s interior: its single exhibition room ‘at the back’ on the ground floor, with a spiral staircase leading down to a ‘basement, storeroom and office’ (the basement where the Camden Town Group exhibitions took place).14 He also sketches a memorable written portrait of Arthur Clifton as an ‘eminently flatfooted’ man with a ‘rather distinguished head’, remarkable both for ‘his shrewd and even generous treatment of artists’ and ability to seem ‘on occasion more discouraging and cold than any man I have ever met’.15 Although many sources note Clifton’s reluctance to support the Camden Town Group beyond its three financially unsuccessful shows, Charles Holmes (1868–1936) was to remember him in his obituary as a dealer with ‘a languid indifference to his commercial interest’ (an image which Nash’s portrait appears to uphold).16 Rather like his counterpart Jack Knewstub at the Chenil, Clifton had a difficult game to play: the Carfax had a reputation as a gallery where cutting-edge contemporary art could be seen, but it also needed to pay the bills. Neither man could afford to be too generous to anyone.

They were, however, seeking a particular type of client; the ‘intellectual visitors’ that Ross recalled frequenting the gallery, who were probably the same class of buyers imagined by Walter Sickert in his vision of ‘little pictures for little patrons’ set out in the New Age in 1910.17 Sickert’s viewpoint was endorsed by fellow artist and friend, Douglas Fox Pitt, who noted that ‘fifteen or twenty guineas a picture is beyond the means of even an “elderly tradesman” with a soul for art’.18 An anonymous correspondent complained in the same journal that he or she would ‘gladly be a “little patron”’, only ‘where am I to go for such pictures?’ Had that writer picked up Holmes’s 1903 guide to Pictures and Picture Collecting (a book addressed ‘particularly to those who have moderate means’) an answer might have been found: ‘Messrs Carfax of Ryder Street,’ Holmes remarked, ‘make a special study of the work of the best of our younger artists.’19

The comparison between the Chenil and the Carfax galleries is worth exploring further; for all their similarities – and there are many – the Carfax differed from Chenil in two significant ways. First, it attempted to balance the financial risks of its contemporary shows by selling Old Masters.20 Secondly, its upmarket location, as noted, may have belied its avant-garde ambitions.21 Indeed, words rather like those used by Beerbohm to describe his fictional Ryder Street resident, the ‘pleasant little’ Hilary Maltby, were regularly employed to describe the Carfax and were proudly reproduced on advertisements for the gallery in the Year’s Art, suggesting that the management saw its small size as a crucial selling point and that they were keen to promote it as an eccentric yet congenial space, where ‘peculiarly interesting’ work might be found.22 In 1910 a critic in the Studio commented that ‘the galleries of Messrs. Carfax have the unique distinction of never being known to have had an uninteresting exhibition. Moreover, their doors are always open to artists who are not bidding for the sensational sorts of reputation.’23 Once again, we have a sense of careful balance: pleasant yet peculiar, always interesting, but not always sensational; an educated mixture of styles that were simultaneously challenging and reassuring.

Throughout its history, it appears that the Carfax sought a balance between its eminently respectable Bury Street address and its quiet but enlightened exhibition programme. It could be argued that the gallery’s Ryder and Bury Street surroundings compromised the Carfax’s sometimes subversive contents (Sickert’s nudes, for example) or by contrast that the gallery was cleverly feeding off the advantages its central London address provided, while subtly undermining the respectability of the district. Rather like the work of many of the artists who exhibited there, the Carfax occupies a middle ground, neither conventional nor consistently innovative: dependably difficult to classify, and something of an antidote to the oppositional approach that could dominate the London art world, in which artists and galleries found themselves swiftly herded into convenient groupings, to be marketed like any other commodity (an approach echoed, more often than not, by our historical approach to the period).

So should we be surprised to find the Camden Town Group exhibiting there? Although his first solo show at the Carfax did not take place until January 1911, Sickert had been associated with the gallery from the start, sending work over from Dieppe to Rothenstein, often accompanied by orders and advice.24 ‘I am so anxious you should avoid every possible small mistake by which custom is at all alienated. Business is a science. The London dealers have not mastered it’, he wrote at one point; and at another castigated Rothenstein for giving his brother Robert a job there (proof, he thought, of Rothenstein’s naivety).25 After Rothenstein gave up his official role at the Carfax, Sickert was less involved, and on his return to London combined his continuing involvement with the Parisian art dealers, Bernheim Jeune, with his new Fitzroy Street venture. In 1911 he was, however, welcomed back into the Carfax fold. Arthur Clifton clearly believed that Sickert was an artist worth investing in and Sickert, likewise, seems to have seen the Carfax as an entirely appropriate space in which to exhibit.

Still, Bury Street was not Fitzroy Street, where many of the Camden Town Group artists had first exhibited together; a location that was, as curator Robert Upstone has noted, ‘somewhat transient and known for unsuitable clubs’; a place where, Sickert hoped, one might attract a ‘milieu rich or poor, refined or even to some extent vulgar’.26 Could the Carfax fulfil a similar role, or did it represent in some ways the failure of Fitzroy Street to attract this very milieu? By staging the Camden Town Group exhibitions at a commercial gallery, they were possibly admitting that the Fitzroy Street venture was not enough on its own. And yet the Carfax represents more than the compromise this comment suggests. Although it would be easy to overestimate the fashionable address, the signs are that the Carfax was capable of rising above its location – and that, ultimately, it was not altogether extraordinary that this ‘pleasant little’ Bury Street gallery should be exhibiting Sickert’s controversial Camden Town nudes.

Notes

Fothergill had spent the last few years collecting antiquaries for Edward Warren. Some sources credit Warren with supplying financial support in the gallery’s early days, but there is no direct proof of this, although Rothenstein and the Carfax did help Warren buy work by Rodin; see David Sox, Bachelors of Art: Edward Perry Warren and the Lewes House Brotherhood, Fourth Estate, London 1991, pp.93–4. Fothergill’s dealings with the Carfax were complicated by the fact that its creation coincided with a period of illness during which he stayed on the continent.

Most famous for his association with Oscar Wilde, Ross had been a good friend of Rothenstein and Fothergill for some years and continued to be close, despite a few complications during the gallery transfer, revolving around missed payments to Rodin; see Maureen Borland, Wilde’s Devoted Friend: A Life of Robert Ross, Lennard, Oxford 1990. Another friend of Wilde’s, More Adey (1858–1942), helped Ross with the gallery certainly around the time of Charles Conder’s exhibitions (Charles Conder papers, UCLA).

For discussion of Sargent’s Carfax exhibitions, see Richard Ormond and Elaine Kilmurray, John Singer Sargent: Venetian Figures and Landscapes, Yale University Press, New Haven 2009, pp.51–4.

Between 1911 and 1920, the gallery held several exhibitions showing the work of Sickert, his pupils and his friends. Sickert’s last exhibition at the Carfax was in 1916. Sickert and Clifton later disagreed over Clifton’s affair with Madeline Knox, Sickert’s former pupil; see Matthew Sturgis, Walter Sickert: A Life, Harper Perennial, London 2005, pp.502–3. For more on Knox, see Tate T13024.

Other artists who exhibited at the Carfax include Philip Wilson Steer (1860–1942), Muirhead Bone (1876–1953), William Orpen (1878–1931), Alfred Rich (1856–1921), Roger Fry (1866–1934) and Charles Ricketts (1866–1931). All but the last were regular NEAC exhibitors. Bernard Shaw is said to have had shares in the gallery; see Michael Holroyd, George Bernard Shaw, vol.2, Chatto & Windus, London 1989, p.171. Cunninghame-Graham was a close friend of Rothenstein, accompanying him to Morocco and Spain in 1894. MacColl started out as art critic for the Spectator in 1890, moving on to the Saturday Review in 1896. In 1906 he became Keeper of the Tate Gallery. As an artist, MacColl regularly exhibited at the NEAC and at the Carfax in April 1906.

We could also include the Goupil Gallery, a much larger space which, under William Marchant’s management, held forward-looking exhibitions. The Carfax was inspired, in its own way, by galleries such as the Van Wisselingh’s Dutch Gallery, where Sickert and Rothenstein both exhibited early on in their careers (Sickert with his brother Bernhard in 1895, Rothenstein with Charles Shannon in 1894).

There is no single good source on the early years of the Carfax, though Rothenstein’s memoirs and unpublished material held at the Rothenstein archives (Houghton Library, Harvard) contain many interesting details. On the Robert Ross years, see Margery Ross (ed.), Robert Ross: Friend of Friends, Jonathan Cape, London 1952 and Borland 1990.

Paul Nash, Outline, Columbus, London 1988, pp.124–9. Nash’s show opened shortly before the third Camden Town Group exhibition.

Wendy Baron, Perfect Moderns: A History of the Camden Town Group, Ashgate, Aldershot and Vermont 2000, p.46. It is not clear why the Camden Town Group shows were held in the basement and not in the exhibition room upstairs, though it is, of course, unlikely that a single room would have been enough.

Clifton continued to support members of the group in solo shows, and the lack of any further group shows may have had just as much to do with a desire for expansion – and the Carfax’s inability to accommodate this; see Wendy Baron, Camden Town Recalled, exhibition catalogue, Fine Art Society, London 1976, p.13, and C.J. Holmes, Times, 7 October 1932 (clipping from Tate Archive TGA 8721/23).

Ross (ed.) 1952, p.139; Walter Sickert, ‘Little Pictures for Little Patrons’, New Age, 11 August 1910, p.358, in Anna Gruetzner Robins (ed.), Walter Sickert: The Complete Writings on Art, Oxford University Press, Oxford 2000, p.271.

Charles Holmes, Pictures and Picture Collecting, Anthony Treherne & Co., London 1903, pp.5, 46–7. Holmes’s support comes as no surprise; he was a close friend of Rothenstein’s and exhibited at the Carfax himself in 1909.

The Chenil was situated on King’s Road, Chelsea; one of the few galleries to ply its trade outside of central London.

Ironic, perhaps, since Sickert was far from a good businessman. Max Beerbohm wrote in 1905 of how he tried to instil Rothenstein’s advice into Sickert, concluding: ‘But I know Sickert so well, and I am sure he will have cleverly muddled away, meanwhile, such chance he had of enriching himself’; Mary M. Lago and Karl Beckson (eds.), Max and Will: Max Beerbohm and William Rothenstein, Their Friendship and Letters, 1893–1945, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA 1975, p.52.

Walter Sickert, letters to William Rothenstein, undated [c.1899–1900], Rothenstein collection, Houghton Library, Harvard, MS Eng 1148. The hapless Robert Sickert was employed as gallery manager early on, but lasted only a few months.

Samuel Shaw completed his doctorate at the University of York in 2010, in which he explored the influence of the artist William Rothenstein between 1890 and 1910. The thesis includes a chapter on the foundation of the Carfax Gallery.

How to cite

Samuel Shaw, ‘The Carfax Gallery and the Camden Town Group’, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://www