After Camden Town: Sickert’s Legacy since 1930

Martin Hammer

In the years following the First World War the influence of Camden Town painting waned but later generations of British artists found inspiration in its approach to realism. Martin Hammer looks at the legacy of the Camden Town Group in the work of such artists as Francis Bacon, Lucian Freud and Richard Hamilton.

By 1930 the art of the Camden Town Group was in some senses a historical phenomenon. In its heyday in the 1910s it had generated a relatively coherent body of work characterised by everyday subject matter and scrupulous first-hand description of form, space and light, underpinned by the pervasive inspiration of Walter Sickert and modern French art. But the impetus behind the movement was undermined by the early deaths of Spencer Gore and Harold Gilman, the most talented of the younger participants, while Sickert himself moved into increasingly personal artistic territories, notably through his use of popular illustrations and photographs rather than direct observation as the point of departure for paintings.

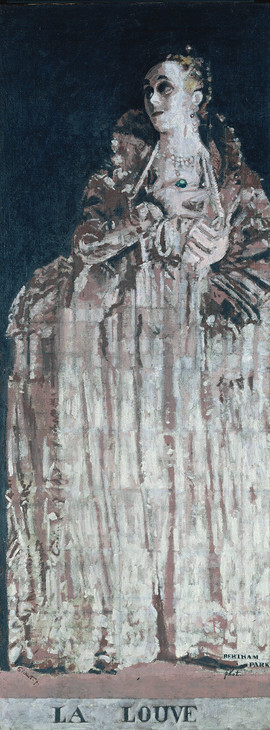

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

Miss Gwen Ffrangcon-Davies as Isabella of France 1932

Oil paint on canvas

frame: 1173 x 115 mm, 92 kg, 2705 mm; support: 2451 x 921 mm

Tate N04673

Presented by the Art Fund, the Contemporary Art Society and C. Frank Stoop through the Contemporary Art Society 1932

© Tate

Fig.1

Walter Richard Sickert

Miss Gwen Ffrangcon-Davies as Isabella of France 1932

Tate N04673

© Tate

For any kind of art to exert an influence it has of course to be available for scrutiny, and in that context exhibitions play a key role. In the 1930s, interest in Camden Town Group painting was mainly sustained by the commercial art market. The two most important exhibitions of the entire group’s production in the 1930s were organised by the Leicester Gallery (1930) and the Redfern Gallery (1939).2 Its surviving members, notably Sickert, also featured regularly in gallery shows. The resonance of such work stemmed mainly from a continuing artistic impulse towards realism as an antidote to what seemed the elitism of modernist approaches such as abstraction or surrealism, just as in the 1910s the group itself had been motivated in part by resistance to the modernist erosion of significant subject matter in favour of ‘significant form’. In the 1930s, once again, this was not just a parochial or conservative position, and it was informed in the minds of some by socialist politics. Realist art for mass consumption and enlightenment was now the official artistic ideology of the Soviet Union, and the idea proved increasingly attractive abroad as politics polarised and the far left appeared the only principled opposition to an emergent Fascism in Europe.3 In Britain, a social realist ethos generated some remarkable experimental and documentary film-making (for example, the output of the GPO film unit) as well as photography (such as Bill Brandt’s record of British social stratification). Other symptoms of the new climate were the Mass Observation commitment to observing working class life in northern England, the polemical art criticism of Anthony Blunt, and the revival of interest in the art of William Hogarth as the model for a native tradition of British populist realism.

Sir William Coldstream 1908–1987

Inez Spender 1937–8

Oil on canvas

support: 770 x 1018 mm; frame: 945 x 1208 x 120 mm

Tate N05883

Presented by the Contemporary Art Society 1949

© The estate of Sir William Coldstream. All Rights Reserved 2010 / Bridgeman Art Library

Fig.2

Sir William Coldstream

Inez Spender 1937–8

Tate N05883

© The estate of Sir William Coldstream. All Rights Reserved 2010 / Bridgeman Art Library

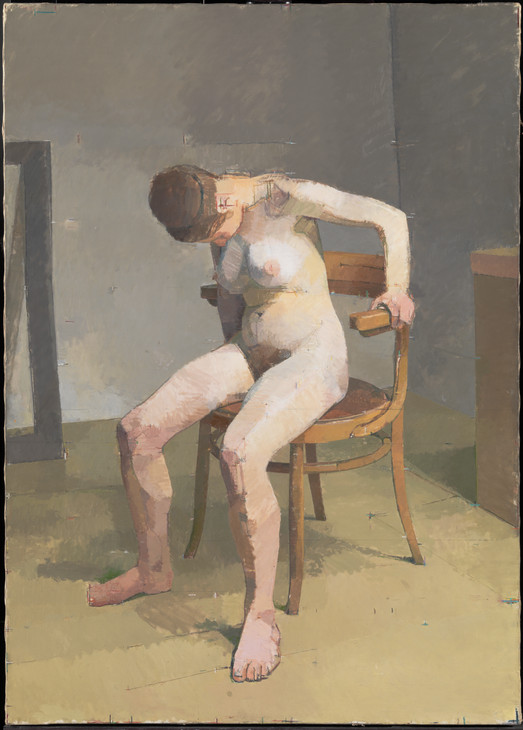

Euan Uglow 1932–2000

Nude 1962–3

Oil on canvas

support: 1632 x 1168 mm; frame: 1632 x 1365 x 105 mm

Tate T00659

Presented by the Trustees of the Chantrey Bequest 1964

© The estate of Euan Uglow

Fig.3

Euan Uglow

Nude 1962–3

Tate T00659

© The estate of Euan Uglow

But this is just one example of continuity amongst many. It is probably fair to say that the art of Sickert and the Camden Town Group was most visible and most widely influential during the decade and a half after the end of the Second World War. Beyond the art colleges, the tradition of British realism was promoted after the war not just by commercial galleries but also by public bodies such as museums and the newly established Arts Council. A series of exhibitions focused on the contributions of the Camden Town and Euston Road School artists.9 Such work demonstrated once again that there could still be artistic possibilities in the human figure, pictorial narrative and subjects from everyday urban existence as progressive alternatives to what appeared the escapism and tastefulness of a prevailing ‘neo-romanticism’ or abstraction.

Sickert above all became a talisman. After his death in 1942, several illustrated books about his life and work appeared, and the artist’s own lively writings on art were brought together in the 1947 volume A Free House.10 A string of posthumous exhibitions culminated in the several displays timed to mark the centenary of his birth in 1960. Over the subsequent fifty years, numerous exhibitions and publications have consolidated his position as one of the key figures in modern British art. The story of the creative provocation and stimulation his art has provided to successive generations of artists is inevitably a complex one. Any art of substance is open to diverse readings, and this is especially true of Sickert’s given the variety of his output over six decades. His work has inspired painters across the pictorial spectrum, from slick academicians applying to conventional subjects a darker-toned variation on the impressionist manner, through to experimental artists such as Howard Hodgkin, a great admirer whose boldly coloured near-abstractions look nothing like Sickert superficially, though they have been said to extend his ‘intimation of human drama through psychological and sexual innuendo’.11

The post-war realist impulse took an overtly Sickertian form in the work of Ruskin Spear, as evident not just in the pub-interior imagery of a picture such as Mr Hollingbery’s Canary (Tate N06011, fig.4) but also in its elaborate perspective, earthy palette and encrusted paint surface. Spear taught at the Royal College of Art, which was ‘dominated by Sickert’s tonality and colour’ according to John Bratby, one of a group of students who after graduation rose meteorically to fame with a kind of art that in 1954 was christened ‘Kitchen Sink’ painting by the critic David Sylvester, capturing the banal ordinariness of its imagery.12 Their work was successfully promoted by the Beaux-Arts Gallery in London, in tandem with work by Sickert, whose sister-in-law Helen Lessore was the proprietor. Kitchen Sink painters were less obviously derivative than Spear, more inclined to bold scale, linearity and the simplification of appearances, but the fusion of low-life subjects and muted, monochromatic colour in the work of Jack Smith (Tate T00005, fig.5) and Edward Middleditch suggests that Sickert was an important inspiration for the group. Moreover scrutinising and reviewing Sickert exhibitions around 1950 had been a formative experience for the young Marxist critic John Berger, who emerged as the most committed spokesman for Kitchen Sink painting, claiming a radical political charge for its ‘deliberate acceptance of the importance of the everyday and the commonplace’.13

Ruskin Spear 1911–1990

Mr Hollingbery's Canary 1950

Oil on canvas

support: 1829 x 1071 mm

Tate N06011

Presented by the Trustees of the Chantrey Bequest 1951

© Tate

Fig.4

Ruskin Spear

Mr Hollingbery's Canary 1950

Tate N06011

© Tate

Jack Smith born 1928

Mother Bathing Child 1953

Oil on board

support: 1829 x 1219 mm; frame: 2034 x 1420 x 107 mm

Tate T00005

Purchased 1955

© Jack Smith

Fig.5

Jack Smith

Mother Bathing Child 1953

Tate T00005

© Jack Smith

Lessore also showed work by Royal College contemporaries of Bratby and co. which generated a more muted response at the time, but acquired more substantial and lasting recognition in the long term. The art of Frank Auerbach in particular has remained profoundly rooted in the example of Sickert, merging with the inspiration he derived from his sometime teacher David Bomberg (who had himself taken drawing classes with Sickert), the early work of Chaim Soutine, and Old Masters such as Rembrandt whom he obsessively studied in the National Gallery. The sheer presence of paint in Sickert becomes hugely magnified in Auerbach’s thickly worked pictures, which also extend and intensify Sickert’s essentially tonal use of browns and ochres, and his preference for extreme contrasts of light and shadow. At the same time, Sickert was one point of reference for Auerbach’s ambition to fuse visceral painterly surface, evoking the massive substance of external reality, with rigorous, often geometric pictorial architecture and with the evocation of immaterial sensations of light. The importance of drawing, as an intermediary between registering observations and constructing design, comprises another shared priority for the two artists. Even the fact that Auerbach has always worked in a studio in Camden, very close to one of Sickert’s own studios, suggests a conscious continuity.

Robert Hughes’s 1989 book on Auerbach gives an account of the artist’s recollections of reading A Free House with great excitement when he was a student and since, and his sense that Sickert was ‘the one painter of real world stature who worked in England in the early part of this century’.14 That enthusiasm is palpable in Auerbach’s earliest independent work. The Sickert nudes that were shown at the Beaux-Arts Gallery in 1953 seem pivotal for early works such as E.O.W. Nude (Tate T00313, fig.6). Lessore’s permanent display of Sickert’s looming self-portrait The Servant of Abraham 1929 (Tate T00259, fig.7) informed Auerbach’s several close-up portraits of Leon Kossoff from the same period and indeed on some level his many subsequent images of heads in which the complexity of three-dimensional forms played upon by light is translated into configurations of paint or charcoal on a flat surface. Kossoff also recalled being ‘knocked out’ when he saw this Sickert and The Raising of Lazarus 1929–30 (Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide) at the Beaux-Arts Gallery, adding that he still sees them as ‘two of the most beautiful paintings of our time’.15

Frank Auerbach born 1931

E.O.W. Nude 1953–4

Oil on canvas

support: 508 x 768 mm; frame: 675 x 943 x 90 mm

Tate T00313

Purchased 1959

© Frank Auerbach

Fig.6

Frank Auerbach

E.O.W. Nude 1953–4

Tate T00313

© Frank Auerbach

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

The Servant of Abraham 1929

Oil paint on canvas

support: 610 x 508 mm; frame: 815 x 717 x 75 mm

Tate T00259

Presented by the Friends of the Tate Gallery 1959

© Tate

Fig.7

Walter Richard Sickert

The Servant of Abraham 1929

Tate T00259

© Tate

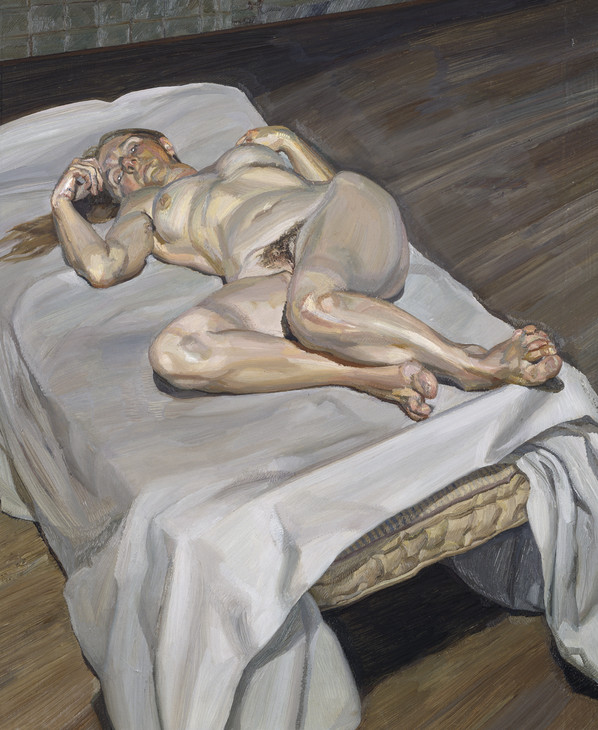

Auerbach and Kossoff have been grouped with two somewhat older painters, Francis Bacon and Lucian Freud, and with their Slade-trained contemporary, Michael Andrews, under the diffuse label ‘The School of London’. An enthusiasm for Sickert was certainly one common denominator behind their otherwise diverse work. In the case of Freud, the neglect by critics of his dialogue with Sickert is symptomatic of a mythology around his work of the innocent eye (‘My method was so arduous that there was no room for influence’), as though his fellow Viennese émigré Ernst Gombrich had not demonstrated that observation is always mediated by artistic conventions and responses, which inevitably shape the decisions an artist makes regarding the choice and treatment of subject matter.16 The most obvious connection is the two artists’ preoccupation with the image of the nude. Freud may well have read Sickert’s 1910 essay on ‘The naked and the Nude’, which denounced the clichés and ‘intellectual and artistic bankruptcy’ of the artistic Nude, placed ‘in opposition to the naked’, calling for a more inventive and realistic approach to such imagery.17 Sickert celebrated the example provided by Edgar Degas, who ‘has incessantly chosen to draw figures from unaccustomed points of view’, and declared that ‘perhaps the chief source of pleasure in the aspect of a nude is that it is in the nature of a gleam – a gleam of light and warmth and life. And so to appear it should be set in surroundings of drapery or other contrasting surfaces.’18

Such attitudes, along with the remarkable pictures by Sickert in which they were given concrete realisation, provide a template for the extended sequence of ‘naked’ images of female and occasionally male sitters that Freud has produced since the late 1960s. The twisted, foreshortened and utterly unidealised bodies laid out for our scrutiny in, say, the two versions of Naked Girl Asleep 1967 and 1968 (private collections), Rose 1978–9 (private collection) or Night Portrait 1985–6 (fig.8), strongly recall Sickert’s frank treatment of the splayed female figure set against white sheeting in a series of images culminating in L’Affaire de Camden Town 1909 (fig.9). In the latter picture, the reclining nude is also juxtaposed against a standing male figure, which must surely have played some part in the conception of Freud’s Painter and Model 1986–7 (private collection), where the roles are inverted and a clothed female painter looms over the naked male, lying fully exposed on the battered leather Chesterfield sofa that replaced the bed in so many Freuds as the arena for displaying his figures. Similarly, in Large Interior W.9 1973 (fig.10), the positioning by Freud of his aged mother seated in front of a nude figure lying on her back, her head framed by her arms and gazing to the ceiling, brings to mind other Sickerts from the Camden Town Murder series with seated males and recumbent naked females. The predominantly brown, ochre and dirty white palette and the atmosphere of psychological dislocation might also suggest a familiarity with Sickert’s unusually monumental and tightly executed Ennui c.1914 (Tate N03846, fig.11), a picture in which the taut build-up of shapes enclosing the two figures and their placement in space loosely corresponds to that of the model’s knees framing the mother’s head and shoulders in the Freud, just as the glass on the table in Ennui establishes a hard geometric note analogous to Freud’s mortar and pestle.

Lucian Freud 1922–2011

Night Portrait 1985–6

Oil paint on linen

927 x 762 mm

Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution, Joseph H. Hirshhorn Purchase Fund, 1987.

© Estate of Lucian Freud

Photo Lee Stalsworth

Fig.8

Lucian Freud

Night Portrait 1985–6

Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution, Joseph H. Hirshhorn Purchase Fund, 1987.

© Estate of Lucian Freud

Photo Lee Stalsworth

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

L'Affaire de Camden Town 1909

Oil paint on canvas

610 x 406 mm

Private collection

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Photo © Photographic Survey, Courtauld Institute of Art

Fig.9

Walter Richard Sickert

L'Affaire de Camden Town 1909

Private collection

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Photo © Photographic Survey, Courtauld Institute of Art

Lucian Freud 1922–2011

Large Interior W.9 1973

Oil paint on canvas

915 x 915 mm

Devonshire Collection, Chatsworth

© Estate of Lucian Freud

Reproduced by permission of Chatsworth Settlement Trustees. Photo John Riddy

Fig.10

Lucian Freud

Large Interior W.9 1973

Devonshire Collection, Chatsworth

© Estate of Lucian Freud

Reproduced by permission of Chatsworth Settlement Trustees. Photo John Riddy

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

Ennui c.1914

Oil paint on canvas

support: 1524 x 1124 mm; frame: 1741 x 1340 x 110 mm

Tate N03846

Presented by the Contemporary Art Society 1924

© Tate

Fig.11

Walter Richard Sickert

Ennui c.1914

Tate N03846

© Tate

Such affinities and allusions, whether or not they were conscious, coexist of course with notable differences across the two artists’ work, beyond the obvious technical distinctions. The narrative and documentary suggestions in Sickert, for instance, highlight the sense of studio staging in the work of Freud, which generally aspires to the condition of portraiture, whereas Sickert’s art references the more impersonal genre tradition. The same argument could be extended to the naked portraits of Henrietta Moraes, mediated by photographs taken by John Deakin, that were created by Freud’s great friend Francis Bacon in the 1960s (fig.12). The conception of the figure here, and the visual interplay in related pictures between fleshy, writhing human body, soft mattress and metallic frame, suggest an awareness of Sickerts such as La Hollandaise c.1906 (Tate T03548, fig.13). Moreover, at a more technical level, looking at this type of Sickert may also have encouraged Bacon to juxtapose very different modes of paint handling within the same canvas, while the white marks in La Hollandaise, floating free from their descriptive purpose, offer an intriguing precedent for the ejaculatory blobs of white paint that become such a recurrent and shocking feature of Bacon’s work from the mid-1960s onwards.

Francis Bacon 1909–1992

Portrait of Henrietta Moraes on a Blue Couch 1965

Oil paint on canvas

1980 x 1470 mm

Manchester City Galleries

© The Estate of Francis Bacon. All rights reserved. DACS 2010

Photo © Manchester City Galleries

Fig.12

Francis Bacon

Portrait of Henrietta Moraes on a Blue Couch 1965

Manchester City Galleries

© The Estate of Francis Bacon. All rights reserved. DACS 2010

Photo © Manchester City Galleries

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

La Hollandaise c.1906

Oil paint on canvas

support: 511 x 406 mm; frame: 722 x 630 x 104 mm

Tate T03548

Purchased 1983

© Tate

Fig.13

Walter Richard Sickert

La Hollandaise c.1906

Tate T03548

© Tate

Further parallels with Bacon indicate that the idea of Sickert as a latter-day realist, in the tradition of his friend Degas and of Hogarth in an English context, was only one perspective on his legacy. A compelling alternative was responding to the element of detachment and creative artifice that became especially evident in Sickert’s work during his final fifteen years, hitherto regarded by many as an eccentric falling away. Artists’ enthusiasm for these works was a key element in their re-evaluation that culminated in the 1981 Late Sickert show at the Hayward Gallery. For Auerbach, writing in the catalogue, this type of Sickert increasingly looked his most inventive and original contribution.19 The curator Richard Morphet identified Bacon in particular as ‘in many ways a direct heir of late Sickert’.20 Indeed Bacon’s viewpoint on Sickert may already be filtered through the critical response of his friend David Sylvester, whose admiration for Bacon culminated in the famous volume of interviews. As early as 1960 Sylvester stated of Sickert, with a sideways glance perhaps towards current pictures by Bacon, that ‘his finest works are the best of his late works – the ones made from squared-up photographs in raw scrubbed colour with their dry graceless paint sinking into the coarse-grained canvas, works which are nothing but the strangeness of the shapes that the eye sees in nature when the mind ... is not allowed to intervene’.21

Francis Bacon 1909–1992

Painting 1950

Oil paint on canvas

Leeds Museums and Galleries (City Art Gallery)

© The Estate of Francis Bacon. All rights reserved. DACS 2010

Photo © Leeds Museums and Galleries (City Art Gallery) UK / The Bridgeman Art Library

Fig.14

Francis Bacon

Painting 1950

Leeds Museums and Galleries (City Art Gallery)

© The Estate of Francis Bacon. All rights reserved. DACS 2010

Photo © Leeds Museums and Galleries (City Art Gallery) UK / The Bridgeman Art Library

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

Camden Town Nude: Conversation c.1908–9

Black chalk heightened with white, pen and ink on buff paper

337 x 235 mm

Royal College of Art, London

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Photo © Royal College of Art

Fig.15

Walter Richard Sickert

Camden Town Nude: Conversation c.1908–9

Royal College of Art, London

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Photo © Royal College of Art

Bacon himself was never one to acknowledge ‘influences’, other than Pablo Picasso and the Old Masters. But recent research has revealed that his enthusiasm for Sickert extended to acquiring Granby Street 1912–13 (private collection), a picture subsequently owned by Freud.22 The art historian Rebecca Daniels has assembled the evidence for several thematic and formal derivations, demonstrating in particular that Bacon’s standing nude in Painting 1950 (fig.14) was directly informed by the Sickert drawing Camden Town Nude: Conversation c.1908–9 (fig.15), a work relating to the Camden Town Murder series which Bacon could certainly have known. Above all, from the early 1940s onwards Bacon’s work drew consistent and overt inspiration from the many kinds of photographic imagery that he was recorded as accumulating in his studio, including grainy press photography, illustrations from books about wild animals, art, cinema and medicine, and Eadweard Muybridge’s studies of the body in motion. As with Sickert, such allusions are combined in Bacon’s painting with visible brushwork and roughly textured canvas. Another recent study has argued that Bacon’s extensive use of Nazi propaganda photography as the springboard for many pictures in the 1940s and 1950s may have been triggered in part by Sickert’s pictorial quotations from modern-life imagery, in particular press photographs of King Edward VIII emerging from his car (fig.16), foreshadowing Bacon’s own adaptation of images of Hitler being driven through the ranks of adoring crowds.23

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

H.M. King Edward VIII 1936

Oil paint on canvas

1834 x 921 mm

The Beaverbrook Art Gallery / The Beaverbrook Canadian Foundation (in dispute, 2004)

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Photo © The Beaverbrook Art Gallery, Fredericton, NB

Fig.16

Walter Richard Sickert

H.M. King Edward VIII 1936

The Beaverbrook Art Gallery / The Beaverbrook Canadian Foundation (in dispute, 2004)

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Photo © The Beaverbrook Art Gallery, Fredericton, NB

Richard Hamilton born 1922

The subject 1988–90

Oil on canvas

support (1): 2000 x 1000 mm; support (2): 2000 x 1000 mm; frame: 2067 x 2099 x 32 mm

Tate T06774

Purchased 1993

© Richard Hamilton

Fig.17

Richard Hamilton

The subject 1988–90

Tate T06774

© Richard Hamilton

Bacon in turn served as a bridge between Sickert and younger artists preoccupied by mass-circulation photographic imagery. The work of Michael Andrews, for example, continued Sickert’s frank emulation of the cool detachment and sometime quirkiness of form and colour encountered in photographic imagery.24 Equally, Bacon was a catalyst to some degree for Richard Hamilton’s fascination with the photographic distillations that mediate our understanding of contemporary history. Yet Sickert’s H.M. King Edward VIII offers an even more direct model for the artistic representation of charged media imagery in Hamilton’s cluster of diptychs addressing the ‘troubles’ in Northern Ireland, comprising The Citizen 1981–3, depicting a republican detainee at the Maze Prison, The Subject 1988–90 (Tate T06774, fig.17), a parading loyalist Orangeman, and The State 1993, which shows a British soldier on patrol.

I have focused here on a generation who established their artistic identities in the years immediately following the war, when Sickert’s work and example were ubiquitous. However, their varied creative appropriations ran in parallel to a wider process of Sickert gradually going out of fashion. Bratby declared: ‘Sickert derivation in 1956 is dishonest and is painting done either by old men who live in times past or by artists who are afraid to face the reality of the times they live in.’25 Sickert’s gloom started to look even more dated as the Swinging Sixties hoved into view. David Hockney recalled that at the Royal College around 1960 ‘Sickert was the great god and the whole style of painting in that art school – and in every other art school in England – was a cross between Sickert and the Euston Road School’.26 The ‘ghost of Sickert’ prevented Hockney from engaging with the London urban scene in the way he could with Los Angeles.27 The late portraits aside, the centenary show at the Tate Gallery prompted only qualified admiration from Sylvester, who took the opportunity to declare that the ‘tragic flaw of English painting is compromise’, epitomised by Sickert’s combination of observation, psychologically charged narrative, painterly touch, and ‘impeccable design’, which for Sylvester merely coexisted in Sickert’s pictures whereas ‘the disparate elements in the work of great artists fuse so that each is inconceivable without the others’.28 As Sickert dropped off the radar, his art could begin to attract more personal kinds of interest. Thus, Richard Billingham discovered his work as a painting student in the late 1980s, and there is a clear thread of connection with his subsequent body of photography in which the domestic environment and somewhat dysfunctional existence of the artist’s parents are disconcertingly exposed. Sickert is now firmly embedded in art history, and a strong body of scholarship has developed around him, but the sheer calibre of his work, I argue, guarantees that it will long continue to excite the admiration and emulation of artists.

Notes

The general phenomenon is surveyed in The Painting of Modern Life: 1960s to Now, exhibition catalogue, Hayward Gallery, London 2007. Wendy Baron has investigated Sickert’s legacy also, see Wendy Baron, ‘The Legacy of Sickert’, in James Hyman (ed.), From Life: Radical Figurative Art from Sickert to Bevan, exhibition catalogue, James Hyman Fine Art Gallery, London 2003, pp.6–11.

See exhibition catalogue listing in Robert Upstone (ed.), Modern Painters: The Camden Town Group, exhibition catalogue, Tate Britain, London 2008, p.179.

The leftist impulse in British art is surveyed in Lynda Morris and Robert Radford, AIA: The Story of the Artists International Association 1933–1953, exhibition catalogue, Museum of Modern Art, Oxford 1983.

For a survey of the group’s historical position and artistic limitations, see Charles Harrison, English Art and Modernism, Allen Lane, London 1981, chapter 12. The fullest account is Bruce Laughton, The Euston Road Group: A Study in Objective Painting, Ashgate, Aldershot 1986.

William Coldstream, ‘Painting’, in R.S. Lambert (ed.), Art in England, Pelican Books, London 1938, pp.100, 102.

Timothy Hyman, ‘The Persistence of Realism in British Painting’, in Chris Stephens (ed.), The History of British Art: 1870–Now, vol.3, Tate Publishing, London 2008, p.112.

James Hyman, The Battle for Realism, Yale University Press, New Haven and London 2001, p.63. This is the best general account of 1950s realism, and contains much material on Sickert’s influence.

Catherine Lampert, Euan Uglow: The Complete Paintings, Yale University Press, New Haven and London 2007. This illustrates the surviving early pictures, though their Sickertian dimension is not noted.

Upstone (ed.) 2008, p.179. The Arts Council’s 1948 show of the Euston Road School is noted in James Hyman 2001, p.63.

Osbert Sitwell (ed.), A Free House, or The Artist as Craftsman, being the Writings of Walter Richard Sickert, Macmillan, London 1947.

Michael Auping, ‘A Long View’, in Howard Hodgkin Paintings, exhibition catalogue, Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, Texas 1996, p.27. Richard Shone tellingly juxtaposes Hodgkin’s In Bed in Venice 1984–8, with Sickert’s Mornington Crescent Nude c.1907, in ‘Walter Sickert: The Dispassionate Observer’, in Sickert: Paintings, exhibition catalogue, Royal Academy, London 1992, p.6.

For more on this essay, see Barnaby Wright, ‘Walter Sickert: ‘The naked and the Nude’’, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, May 2012, http://www.tate.org.uk/art/research-publications/camden-town-group/barnaby-wright-walter-sickert-the-naked-and-the-nude-r1104376 , accessed 21 August 2013.

Walter Sickert, ‘The naked and the Nude’, New Age, 21 July 1910, pp.276–7, in Sitwell (ed.) 1947, pp.323–7, and Anna Gruetzner Robins (ed.), Walter Sickert: The Complete Writings on Art, Oxford University Press, Oxford 2000, p.261.

Frank Auerbach, ‘Foreword’, in Late Sickert: Paintings 1927 to 1942, exhibition catalogue, Hayward Gallery, London 1981, p.7.

See Rebecca Daniels, ‘Francis Bacon and Walter Sickert; “images which unlock other images”’, in Martin Harrison (ed.), Francis Bacon: New Studies, Steidl, Göttingen 2009, pp.56–87.

Martin Hammer and Chris Stephens, ‘“Seeing the story of one’s time”: Appropriations from Nazi Photography in the Work of Francis Bacon’, Visual Culture in Britain, Special Issue: Bacon Reframed: A Themed Issue on Francis Bacon, vol.10, no.3, November 2009, pp.315–52.

Martin Hammer is Reader in History of Art at the University of Edinburgh.

How to cite

Martin Hammer, ‘After Camden Town: Sickert’s Legacy since 1930’, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://www