Camden Town Recalled

Wendy Baron

When Walter Sickert returned to London from France in 1905, he set about creating an informal grouping of fellow artists that later evolved into the Camden Town Group. In this essay first published in 1976, Wendy Baron describes the background to the group’s formation and how the painters began to find poetry in the ‘interpretation of ready-made life’.

The story of how the north-west suburb of London known as Camden Town came to lend its name both to a style of painting and to a society of artists begins with Walter Sickert coming back to London in 1905 after nearly seven years residence abroad. On his return he rented several studios. Two were in the Fitzroy Street area south of the Euston Road which divided the boroughs of St Marylebone and St Pancras. However, he soon acquired living accommodation and a studio in Mornington Crescent.

This fine curved terrace, which then faced on to leafy gardens (see Gore, Mornington Crescent, Tate N05099), terminates the area of Camden Town (stretching from the Regent’s Park Chester, Cumberland and Cambridge Terraces on the west to Hampstead Road on the east) conceived by Nash and rapidly developed during the first half of the nineteenth century. Behind the elegant residences facing the park Nash planned a service background, with three markets (Cumberland, Clarence and York) and a criss-cross network of little streets lined with well proportioned but relatively modest houses. The area to the east of Hampstead Road was developed shortly afterwards. Almost as soon as the handsome houses were completed the district was blighted by the arrival of the railways. The construction of three great termini, Euston, King’s Cross and St Pancras, brought dirt, noise and a shifting population of navvies into the area. Large tracts of land were destroyed for living purposes and property in neighbouring streets fast declined in value. Houses built as substantial middle class residences were divided into temporary lodgings for a working class population.

William Ratcliffe 1870–1955

Clarence Gardens c.1911–12

Oil paint on canvas

266 x 502 mm

Southampton City Art Gallery

© Estate of William Ratcliffe

Courtesy of Wendy Baron. © Southampton City Art Gallery, Hampshire, UK / The Bridgeman Art Library

Fig.1

William Ratcliffe

Clarence Gardens c.1911–12

Southampton City Art Gallery

© Estate of William Ratcliffe

Courtesy of Wendy Baron. © Southampton City Art Gallery, Hampshire, UK / The Bridgeman Art Library

Sickert, the New English Art Club, and the ‘London Impressionists’

The central role played by Sickert in both the Fitzroy Street and Camden Town Groups is best understood against the background of much earlier efforts to influence his contemporaries towards collaborative activities. In 1888 Sickert joined the New English Art Club where, in April, his four foot high portrayal of Katie Lawrence behind the footlights at Gatti’s Hungerford Palace of Varieties shared the honours with Philip Wilson Steer’s even larger evocation of bathers on a beach entitled A Summer’s Evening.2 He enthusiastically predicted, in a letter to Jacques-Émile Blanche, that the NEAC ‘will be the place I think for the young school of England’.3 However, the idealistic impetus which had inspired the creation of the club in 1886, as an exhibiting body prepared to accept the work of painters aware of recent innovations in France, was already foundering. Its members split up into mutually antagonistic factions of which the most progressive centred around Steer. The brilliant colours and increasingly broken touch of Steer’s light-drenched visions of young girls at the English seaside were derived from French impressionism, a source disapproved of by most critics and many of Steer’s fellow members at the NEAC. Whereas Steer’s avant-garde reputation was earned by his handling rather than by his subject matter, the reverse was true of Sickert. He was vilified for finding the bawdy cockney music hall a proper subject for painting. Trained by Whistler in the arts of political manoeuvring and polemics, Sickert was a valuable addition to the Steer clique. While tactfully lying low at official club meetings and exhibiting only one picture in 1889 (Collin’s Music Hall, Islington Green),4 he busied himself behind the scenes, trying to recruit sympathetic new members, and conspiring to secure control of the selecting jury by his own faction. He also organised the independent exhibition of this group at Goupil’s Gallery in December 1889 under the title ‘London Impressionists’. As author of the catalogue preface he acted as their spokesman.

The ten exhibitors were friends, sympathetic to each other’s aims. They were not members of a common movement and the term ‘Impressionist’ could properly be applied only to Steer. D.S. MacColl, pointing out that ‘Impressionism’ was then ‘the nickname for any new painting that surprised or annoyed critic or public’, suggested that the group was christened by their dealer as ‘a rough and ready means of attracting popular attention’.5 However, it is more likely that the exhibition was christened by Sickert, whose keen appreciation of the publicity value of catchy, even if misleading, appellations is amply demonstrated by the titles of both his pictures and his written articles. Indeed ‘London Impressionists’, as a description of the ten exhibitors at Goupil’s, merely anticipates the inaccuracy of ‘Camden Town’, as a definition of the group of sixteen who exhibited at the Carfax Gallery in 1911. Certainly neither the management of Goupil’s (who in April 1889 had exhibited twenty ‘Impressions by Claude Monet’), nor Sickert, were in any doubt about the true meaning of the term ‘Impressionism’. How Sickert delicately evaded coming to grips with the issue in his catalogue preface is not relevant here. It is of interest, in view of critical reaction to later developments in Camden Town, that he rejected ‘realism’, defined as the wish to record something ‘merely because it exists’ which involved the artist in ‘a struggle to make intensely real and solid the sordid or superficial details of the subjects it selects’.6 Nevertheless, he urged the painter to seek beauty in his everyday urban surroundings. He also articulated his passionate belief that what mattered above all in a painting was ‘quality’, the fitness of its execution (even if this seemed ‘ragged’ or ‘capricious’) to the expression of the artist’s response to his subject. His lifelong creed was already formulated.

Although the ‘London Impressionists’ never again exhibited as a self-contained group, Sickert did not relax his attempts to publicise their activities. Two to three years later, in his Glebe Place studio, Sickert held the first one-man exhibition of Steer’s work. He wrote the catalogue preface to the first exhibition of another ‘London Impressionist’ colleague, the watercolourist Francis James, held at the Dudley Gallery in 1890. In a letter to Nan Hudson of 1907,7 prophesying that the group of painters he was then organising into concerted activity in Fitzroy Street would ‘slowly do very useful things in London’, he remarked ‘I have accomplished a great deal in that way’ and cited both these early efforts as precedents.

Prelude to emigration

However, as the 1890s progressed, Sickert and his colleagues gradually drew apart, separated as much by their different temperaments as by their different preoccupations as painters. None possessed Sickert’s restless energy, nor his fierce professionalism. Moreover the motive for their struggle was gone. The Steer faction gradually gained control of the New English jury and, with the resignation of other groups, came to dominate the club. Their prestige and authority were boosted when Steer’s original champion and one of the ‘London Impressionists’, Fred Brown, was appointed Slade Professor in 1892, and when such sympathisers as George Moore, D.S. MacColl and R.A.M. Stevenson were appointed art critics to the Speaker, the Spectator and the Pall Mall Gazette respectively.

Only Steer and Sickert among the ‘London Impressionist’ group had ever been innovators. As the decade moved on, Steer abandoned the dazzling stippled handling of his early works. He painted landscapes, portraits, and (long before Sickert) informal figure studies, including nude subjects. However, from about 1894 onwards, he turned from impressionism and from the direct spontaneous observation which informed his intimate figure subjects, and began to pillage a bewildering range of largely traditional pictorial sources. To quote Bruce Laughton, ‘in his figure paintings ... there is a continuous regressive change, as it were, back through evocations of Manet and Velasquez to a rather dusty version of French rococo. The landscapes ... became uninhibited and old-masterish’.8 Sickert found himself isolated as the only one of the group who was still experimenting and exploring in an effort to discover and develop his independent artistic personality. While faithful to the tonal tradition in which he had been reared by Whistler, Sickert recognised its dangerous tendency towards oversimplification. Many experiments during the 1890s, in both his landscapes and his portraits, were directed towards discovering means of avoiding Whistlerian slightness of form and content. Monumental design (for instance in head-on collisions with St Mark’s facade); the use of deep, opaque colours; an extension of his tonal scale with the intermediate gradations excised (particularly in his night scenes of Venice, Dieppe and the Cumberland Market region); the broad, untidily slashed brushwork of some of his portraits and landscapes later in the decade – these were among his methods of rejecting the subdued, discreet effects favoured by Whistler and his followers. Although Sickert tackled only one major music hall subject during the 1890s, the Gallery of the Old Bedford, Camden Town (painted in several versions),9 this picture demonstrates that he could transcend the influence of Degas as well as of Whistler. His earlier Degas-inspired representations of a floodlit stage seen behind silhouetted heads in a darkened auditorium (revived by Gore in the next century) are forgotten as Sickert concentrated on the rapt occupants of the gallery. He omitted all reference to the stage. The sophistication of his design produced compositional and psychological tensions which did not need explicit support or explanation. When Sickert returned to the music hall as a subject for painting in 1906 it was the spectators, often in the gallery, who recaptured his attention.

Although Sickert was essentially independent, he did not relish isolation. Personal difficulties contributed to his depression and disillusion in the latter half of the 1890s. His marriage broke down. He was publicly rejected by his former master Whistler. In the winter of 1898 he decided that he could no longer tolerate the apathetic insularity which characterised his professional colleagues in Britain. He escaped across the Channel, gave up portrait painting, and settled down to paint the architecture of Dieppe.

Sickert’s residence abroad 1898–1905

Dieppe remained Sickert’s base until 1905. He punctuated his residence there with several long visits to Venice, and Venetian landscapes helped relieve the monotony of his concentration on the topography of Dieppe. Then, at the age of forty-three, on his visit to Venice of 1903–4, Sickert discovered a new and consuming interest in painting figures in his shabby rooms on the Calle dei Frati.10 Back in Dieppe he continued to paint intimate figure subjects, posing his mistress, the doyenne of the fish-market Madame Villain, nude on the tousled sheets of an iron bedstead.

During his absence Sickert maintained some contact with England, and even made fleeting visits to London. He occasionally sent his work over for exhibition at the NEAC, although he had resigned his membership in 1897. Ernest Brown of The Fine Art Society arranged to exhibit some of his landscape drawings in London. However, Sickert’s main link with London was sustained through his friendship with William Rothenstein. Rothenstein, once his pupil, now worked in an advisory capacity for the Carfax Gallery which began acquiring Sickert’s work in 1899. The gallery had been started in 1898 by a young painter and archaeologist John Fothergill; its staff then included Arthur Clifton (in charge of the business side) and Sickert’s younger brother Robert. It was William Rothenstein’s younger brother Albert (later Rutherston) who, on a painting trip in Normandy with Walter Russell and Spencer Frederick Gore, took Gore to visit Sickert in Dieppe. Sickert’s reputation, as the enfant terrible of British art during the later 1880s and the 1890s, had survived his absence. Gore had probably seen his pictures at the NEAC. Sickert for his part was hungry for news and presumably questioned his visitor about the talent of the new generation of Slade-trained painters. Gore had studied at the Slade from 1896–9, coinciding or overlapping not only with Albert Rothenstein, but also with Harold Gilman, Wyndham Lewis and Augustus John.

It is probable that Gore’s account of these young painters’ gifts encouraged Sickert to consider returning to London. He had exhausted his interest in painting the architecture of Dieppe. It may also have occurred to him that London, with its drab sleazy suburbs, full of dusty high-ceilinged rooms barely letting the cold grey light filter through begrimed windows, was the ideal setting for the kind of figure pictures he longed to paint. He was later to advise Nina Hamnett to exploit the unique flavour of English subjects in her painting: ‘Aren’t we canaille enough for you?’, he asked, ‘Didn’t Doré and Géricault find English life sordid enough?’11 Almost certainly Sickert envisaged and welcomed the probability that in London he might once again orchestrate the careers of his colleagues. Gore and his generation evidently needed the support of a mature, established, but nonetheless independent and original, artist. Steer, who now taught at the Slade, was not prepared to enter the fray on behalf of his young pupils. The NEAC had become almost as tame and conservative in its approach to new talent as was the Royal Academy. An active role awaited Sickert in London.

Sickert’s return to London and his relationship with Gore

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

Noctes Ambrosianae 1906

Oil paint on canvas

635 x 762 mm

Nottingham City Museums and Galleries

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Photo © Nottingham City Museums and Galleries

Fig.2

Walter Richard Sickert

Noctes Ambrosianae 1906

Nottingham City Museums and Galleries

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Photo © Nottingham City Museums and Galleries

Unknown to Sickert the author of this remark was Walter Bayes, a painter in oils and watercolour, who since 1890, when he was still a student, had exhibited with the Royal Academy. Bayes had to wait two years for his work to be discovered by Sickert. In 1906 Sickert’s closest associates were the Rothenstein brothers and, above all, Gore. The earliest paintings to survive by Gore are a few tentative Normandy landscapes of 1904 which reveal the influence of Corot. In 1905 he went to central France, where the constructive perspective of his wide-ranging views around Billy on the river Allier suggests that he was grafting knowledge of seventeenth-century Dutch landscape onto his training by Steer at the Slade.

The influence of Sickert on Gore’s decision to take up the popular theatre as a subject for painting has been overemphasised. Frederick Gore has told how early drawings proved his father’s fascination with Goya’s carnival scenes.13 A visit to Madrid with Wyndham Lewis in 1902 may have reinforced Gore’s attraction to the romantic expressionism of Spanish art. Certainly The Masked Ball of 1903,14 perhaps Gore’s first music hall painting, reveals a streak of lunatic fantasy and licence far closer to Goya than to Sickert. Gore revelled in the riot of colour at his favourite hall, the Alhambra in Leicester Square, which specialised in spectacular ballet displays, with luscious backdrops and ornate costumes. Sickert never painted there. Very occasionally the older man’s influence surmounted Gore’s more exotic taste. Sitting side by side at the New Bedford in Camden Town they drew the same view.15 In Rinaldo (private collection),16 Gore forsook his own preference for pure colours in favour of Sickert’s muted ranges of browns and ochres. The free, slashed application of thinner paint also refers to Sickert, although Gore’s personality seeps through in his choice of a mad violinist as subject. Moreover, soon after Gore painted this picture, he painted The Balcony at the Alhambra (York City Art Gallery)17 and ‘The Mad Pierrot’ Ballet at the Alhambra (private collection, Adelaide), which in style and treatment announce a total break with Sickert. The Balcony introduces the brilliant phase in Gore’s career, cut short by his premature death, during which he explored a novel combination of post-impressionist sources to produce pictures of everyday life ruthlessly reduced to their essential formal components of constructive design and colour.

Pictures of music halls did not become a part of the vocabulary of Sickert’s London associates other than Gore. As we have seen, Gore might well have come to this subject without Sickert’s help. Remembering the disparity in their ages (Sickert forty-six in 1906, Gore twenty-eight) it is arguable that Gore might independently have developed his interest in all sorts of Sickertian subject matter, lodging house interiors, portraits of humble models, and nudes on metal bedsteads or at their toilets. However, as it happened, Sickert was directly responsible for taking Gore straight from his relatively conventional landscape paintings into the studio, and there introduced him to the themes which established the identity of Camden Town painting.

Sickert had himself been painting intimate interiors only since 1903. In London, from 1905–6, besides continuing with his series of nudes on metal bedsteads begun in Dieppe in 1902,18 he had been developing his ability to integrate his figures (clothed and unclothed) and their settings into pictures which appeared convincing as an aspect of ordinary life. In 1906 he worked at this problem alongside Gore in his Mornington Crescent studio. Sickert’s contre-jour nudes and Gore’s Behind the Blind imply close collaboration.19

In the summer of 1906 Sickert lent his house at Neuville to Gore and joined him there for a few weeks. Four years later Sickert attributed his own earlier effort to recast his painting ‘and to observe colour in the shadows’ partly to the influence of Gore.20 In his Dieppe landscapes of 1906 Gore’s observation of colour in the shadows was still haphazard. Although his colours tended to be brighter and his execution more broken than Sickert’s at this date, he was not yet using the pure colours on a white ground, the constructive pointilliste brushwork, and the divided tones which became general in his work from 1907 onwards. Indeed, the objective statement, the sharply drawn accents, and the reddish-brown tonality of Gore’s small-scale panoramic studies of Dieppe done in 1906 suggest he had difficulty in overcoming the Sickertian approach to the sketching of landscape.21

Sickert went on to Paris from Neuville in 1906. He spent the autumn and part of the winter painting nudes in his hotel room and studying, for the first time, the music halls of Paris. Because he delayed in Paris Sickert could not serve, as promised, on the NEAC jury that winter, although he did send over for exhibition the pictures welcomed by Bayes. Gore, who had shown two French landscapes with the club in the summer, had one of his Neuville landscapes accepted for the winter exhibition. Meanwhile in Paris Sickert prepared for a big one-man show of his work at Bernheim-Jeune to open in January 1907 and he exhibited ten pictures at the Salon d’automne. When viewing this Salon Sickert was much impressed by a painting of Venice, Le Canal de la Giudecca,22 by a lady listed as Mme Hudson with an address in Paris. He contemplated writing to the unknown artist to request an exchange of pictures. In the spring of 1907 he discovered that Mme Hudson was the American Miss A.H. (Nan) Hudson whom he had already met in Paris and in London where she lived with the American-born Miss Ethel Sands.

Formation of the Fitzroy Street Group

Malcom Drummond 1880–1945

19 Fitzroy Street c.1913–14

Oil paint on canvas

710 x 508 mm

Laing Art Gallery, Tyne & Wear Archives & Museums

© Estate of Malcolm Drummond

Photo © Laing Art Gallery, Tyne & Wear Archives & Museums

Fig.3

Malcom Drummond

19 Fitzroy Street c.1913–14

Laing Art Gallery, Tyne & Wear Archives & Museums

© Estate of Malcolm Drummond

Photo © Laing Art Gallery, Tyne & Wear Archives & Museums

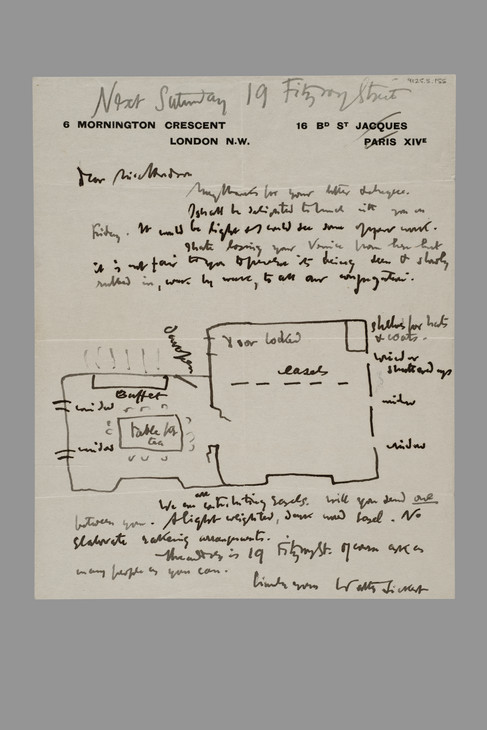

I do it for 2 reasons. Because it is more interesting to people to see the work of 7 or 9 people than one and because I want to keep up an incessant proselytizing agency to accustom people to mine and other painters’ work of a modern character. Every week we would put something different on the easels. It is agreeable sometimes to show something ‘lucky’ you have done at once to anyone it may interest. All the painters interested could keep work there and would have keys and could show anything by appointment to any one at any time ... I want to create a Salon d’automne milieu in London and you could both help me very much.

Ethel Sands and Nan Hudson accepted the invitation, although their busy social lives did not permit attendance each Saturday. Nineteen Fitzroy Street was not immediately ready for use and the first selected gatherings of the Fitzroy Street Group were still held at Sickert’s studio at 8 Fitzroy Street. Urging Ethel Sands and Nan Hudson to send two pictures each for the last of the ‘At Homes’ at No.8, Sickert expanded on his aims for the future:

Accustom people weekly to see work in a different notation from the current English one. Make it clear that we all have work for sale at prices that people of moderate means could afford. (That a picture costs less than a supper at the Savoy.) Make known the work of painters who already are producing ripe work, but who are still elbowed or kept out by timidity etc. ...

And of course no one will feel we are jumping at the throats to buy. That comes of its own accord. People pay attention to things seen constantly and judiciously explained a little.

Further I particularly believe that I am sent from heaven to finish all your educations!! And, by ricochet, to receive a certain amount of instruction from the younger generation.

And of course no one will feel we are jumping at the throats to buy. That comes of its own accord. People pay attention to things seen constantly and judiciously explained a little.

Further I particularly believe that I am sent from heaven to finish all your educations!! And, by ricochet, to receive a certain amount of instruction from the younger generation.

It is interesting that Sickert felt that his group represented the younger generation; that he felt their work, within an English context, was modern; and that he believed them to be struggling against the establishment. At forty-seven Sickert was the oldest of the group, but Russell was only seven years his junior. All except Gore and Albert Rothenstein were over thirty. Furthermore of the eight original members three belonged to the NEAC establishment (Sickert, Russell and William Rothenstein), serving on its juries and committees. Albert Rothenstein was a member of the NEAC, and Gore usually had his work accepted for exhibition. Russell, a close friend of Gore, had exhibited at the Royal Academy since 1898, and since 1895 had been Assistant Professor at the Slade. Nothing in his fresh and charming portraits or landscapes could possibly have offended public and critics in 1907. Sickert seems to have been tilting at windmills. Perhaps his memories of the 1880s led him to identify the NEAC with the modern movement in British art. Recollection of his early battles inspired him to recruit George Thomson, one of the ‘London Impressionists’ of 1889, who was now a teacher of perspective at the Slade and head of the Department of Art at Bedford College.24 Lucien Pissarro, another respected member of the NEAC, was invited to join the group in the autumn. Sickert was delighted when the £2 collected from each member enabled him to buy not only gas-fittings but also chairs ‘like at the New English 21 shillings a dozen’. Nan Hudson was again the recipient of Sickert’s views on how the group should conduct itself:

I want, (and this we can all understand and never say) to get together a milieu rich or poor, refined or even to some extent vulgar, which is interested in painting and in the things of the intelligence, and which has not ... an aggressively anti-moral attitude. To put it on the lowest grounds, it interferes with business.

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

Letter to Anna Hope (Nan) Hudson 1907

Tate Archive TGA 9125/5, no.155

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert

Fig.4

Walter Richard Sickert

Letter to Anna Hope (Nan) Hudson 1907

Tate Archive TGA 9125/5, no.155

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert

one Gore – £10 – to Mrs Donaldson Hudson

one watercolour Russell – £10 – to Walter Taylor

one panel by me – £5 – to Mrs Donaldson Hudson

one sketch by me – £5 – a present from Mr Taylor to Miss Russell.

one watercolour Russell – £10 – to Walter Taylor

one panel by me – £5 – to Mrs Donaldson Hudson

one sketch by me – £5 – a present from Mr Taylor to Miss Russell.

Camden Town painting

Although the Fitzroy Street Group was never intended to represent a movement or school of painting it did come to nurture a distinct and important episode in the history of British art which is most accurately described as Camden Town painting. What is thought of as Camden Town painting is compounded of several characteristics. The pictures tended to be small: ‘little pictures for little patrons’, to quote Sir Louis Fergusson.25 Its favourite themes established an unmistakable vocabulary: nudes on a bed, at their toilet, or just naturally inhabiting their shabby bed-sitters in Camden Town; clothed figures in humble interiors; portrait studies of coster models; mantelpiece still-lifes of cluttered bric-à-brac rather than tasteful arrangements of objets d’art; and landscapes of commonplace London streets, squares and gardens, or during the summer, of the bustling port and narrow streets of Dieppe. Sickert, but not the others of his group, developed a peculiar brand of conversation piece. He embellished his two-figure subjects with spurious anecdotal interest by adding piquant titles such as ‘That Boy will be the Death of me’.26 The titles were afterthoughts, and therefore interchangeable. For example, two paintings (private collection and Kirkcaldy Art Gallery),27 each a study of filtered light dissolving the form of a nude reclining woman into myriad particles and, by contrast, throwing the figure of a clothed man seated at her side into contre-jour relief, have been variously known as The Camden Town Murder, What shall we do for the Rent? and Summer Afternoon.

Another characteristic of Camden Town painting is closely related to its vocabulary. Every theme was treated with objective perceptual honesty. The method taught by Sickert, and adopted by many of his close colleagues, was to work from drawings in which the relationships of figures and objects to their settings and to each other were recorded with dispassionate accuracy. The objective approach did not imply indiscriminate transcription of everything before the painter’s eye. ‘Realism’ as defined by Sickert in his ‘London Impressionist’ catalogue preface (the ‘struggle to make intensely real and solid the sordid or superficial details’ of its subjects) was not its aim. On the contrary, selection was essential, so long as the selection was dictated by the individual temperament of the painter and reflected his honest visual response to the subject rather than his preconceptions of picture making. Only deliberate artifice was rejected.

Sickert, virtually single-handed, inspired both the vocabulary and the objective perceptual approach of Camden Town painting. In his ‘London Impressionist’ catalogue preface he had asserted that magic and poetry were to be found in the everyday urban surroundings of the artist. He himself found beauty in the cockney music halls. Presumably, as a disciple of Whistler, he accepted Whistlerian Thames and Chelsea landscapes as pictures of everyday subjects. However, in 1908, he published his mature reassessment of Whistler’s production which he now believed to have been vitiated by the infiltration of the artist’s ultra-refined taste and dandified personality:

Taste is the death of a painter. He has all his work cut out for him, observing and recording. His poetry is in the interpretation of ready-made life. He has no business to have time for preferences.28

In a series of articles he inveighed against the tastefulness and the ‘puritan standards of propriety’ to which Sickert attributed the ‘insular decadence’ of British painting.29 In 1910 he wrote perhaps his most quoted dictum:

The more our art is serious, the more will it tend to avoid the drawing-room and stick to the kitchen. The plastic arts are gross arts, dealing joyously with gross material facts ... and while they will flourish in the scullery, or on the dunghill, they fade at a breath from the drawing-room.30

In the same year he advised the artist to follow the typical little drab, deliciously personified as ‘Tilly Pullen’, into the first shabby little house, into the kitchen or better still into the bedroom.31

The fact that pictures of less than beautiful nudes on iron bedsteads have come to personify Camden Town painting is an historical distortion directly attributable to the dominant position Sickert held within the Fitzroy Street Group. Besides Sickert only Gore, from 1910 Gilman, and occasionally Malcolm Drummond,32 painted intimate, as opposed to idealised, nude subjects. However, Sickert’s treatment of the subject was so powerful that even his contemporaries tended to overlook the rest of his production. With his flair for publicity Sickert borrowed the title ‘The Camden Town Murder’ (as the press christened the murder of Emily Dimmock in September 1907) for many of his pictures representing a nude female and a clothed man. The pictures were in no sense recreations of the event. Sickert’s juxtapositions of naked and clothed figures were primarily dictated by aesthetic principles. He declared that Le Bain Turc by Ingres,33 a composition consisting entirely of nude figures, suggested ‘an effect like a dish of spaghetti or maccheroni’.34 He expressed his own preferences in 1910:

The nude occurs in life often as only partial, and generally in arrangements with the draped ... Perhaps the chief source of pleasure in the aspect of a nude is that it is in the nature of a gleam – a gleam of light and warmth and life. And that it should appear thus, it should be set in surroundings of drapery or other contrasting surfaces.35

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

Le Lit de cuivre c.1906

Oil paint on canvas

407 x 508 mm

Private collection

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Fig.5

Walter Richard Sickert

Le Lit de cuivre c.1906

Private collection

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

The last major characteristic of Camden Town painting was the handling developed by a nucleus of Fitzroy Street artists whose work represents a late flowering of English impressionism. This characteristic is both the easiest to define and the hardest to confine to Camden Town. Several artists who may be called Camden Town painters (such as Drummond and Sickert) flirted only temporarily with this handling. To others, such as Bevan, Gore and to a lesser extent Gilman, it was an important stage in their development. The landscape painters, Pissarro and Manson, used it consistently but they hardly qualify as Camden Town painters on other grounds. What can be accepted is that interest in colour analysis and the development of a broken touch were characteristics of handling typical of many painters belonging to the Fitzroy Street Group between 1907 and 1911.

Lucien Pissarro, eldest son of the classic French impressionist Camille Pissarro, was the chief inspiration behind this development. He had settled in England in 1890, but for many years devoted his main energies to the design, illustration and printing of books for the Eragny Press which he had created in 1894. His paintings were seldom seen in England until he began exhibiting at the NEAC in 1904. He became a member in 1906. His suburban and rural landscapes were deeply influenced by his father. While his pictures of railway cuttings at Acton38 hark back to Camille Pissarro’s Lordship Lane Station, Dulwich of 1871 (Courtauld Gallery, London), most of his sensitive, scrupulously realised landscapes were executed in solid pigment, applied in separately coloured touches of light-toned pure colour, closely derived from his father’s later, more neo-impressionist, treatment. Lucien, like his father, ignored the rigid scientific basis of neo-impressionism, which predetermined the colour of each touch of paint, yet adopted the characteristic disciplined pointilliste execution developed to express this theory. By temperament he preferred the constructed design of neo-impressionism to the more haphazard and spontaneous compositions of the original impressionists.

Lucien Pissarro’s painting deeply impressed Gore just when he needed guidance to help him emerge from the influences of Steer, Corot and the Dutch landscape tradition. He was already naturally inclined to the use of brighter, purer colour than many of his contemporaries. Lucien Pissarro’s example showed him how to manipulate his colours and control his touch. Gore’s ready assimilation of Pissarro’s method is demonstrated not only in the landscapes painted on a trip to Yorkshire with Albert Rothenstein and Mr and Mrs Walter Russell during the summer of 1907; 39 his response was also sufficiently sensitive to allow him to adapt his new execution to the painting of music halls and portraits. His Some-one waits (City Museum and Art Gallery, Plymouth),40 with the model seen against a window and a portrait of Sickert tucked into a corner, probably influenced Sickert’s portraits of Little Rachel painted in the summer of 1907.41 It should be added that the first evidence of Pissarro’s influence on Gore antedated his membership of Fitzroy Street by some months.

Sickert’s position was curious. Unlike Gore he had known Lucien Pissarro since the 1890s, and he had first-hand acquaintance with French impressionism and neo-impressionism. Also unlike Gore, he was a mature artist who had long since found his own ways of outgrowing dependence on his early training. From time to time, since the 1890s, Sickert had experimented with broken brushwork, and in his landscapes and figure pictures of 1906 he had begun to use small dabbed touches of thicker paint. His colours were, however, still based on blacks, browns and greens. Although Sickert seems to have telescoped the dating we must accept as accurate the sources he acknowledged in 1910 when he gave a retrospective account of his development:

About six or seven years ago, under the influence of Pissarro in France, himself a pupil of Corot, aided in England by Lucien Pissarro and by Gore (the latter a pupil of Steer, who in turn learned much from Monet), I have tried to recast my painting entirely and to observe colour in the shadows.42

Walter Richard Sickert 1860–1942

The Juvenile Lead (Self-Portrait) 1907

Oil paint on canvas

458 x 510 mm

Southampton City Art Gallery

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Photo © Southampton City Art Gallery, Hampshire, UK / The Bridgeman Art Library

Fig.6

Walter Richard Sickert

The Juvenile Lead (Self-Portrait) 1907

Southampton City Art Gallery

© Estate of Walter R. Sickert / DACS

Photo © Southampton City Art Gallery, Hampshire, UK / The Bridgeman Art Library

This type of handling never became a formula for Sickert. He merely assimilated the use of thicker paint, applied in broken touches of lighter and brighter colour, into his technical repertoire. In his pictures of 1907–10 he made free use of the variety of texture, brushwork and colour it afforded to paint such pictures as The New Home of 1908 (private collection),48 the quintessence of Camden Town portraiture and the direct prototype of such pictures as Gore’s North London Girl (Tate T00027) and Sally, the Hat (private collection),49 a scintillating study of a nude bathed in shimmering light.

In 1910 Sickert attributed the evolution of the method of painting ‘with a clean and solid mosaic of thick paint in a light key’ to the combined efforts of a group of artists (‘for these things are done in gangs, not by individuals’) belonging to the NEAC.50 He was probably thinking of the Fitzroy Street offshoot of the NEAC rather than the club proper. In Fitzroy Street this handling developed in a direct line from Lucien Pissarro to Gore, and then in modified form to Sickert. In his Brittany landscapes of 1907 J.B. Manson, Paris-trained but as yet unknown to Fitzroy Street and to his great friend Lucien Pissarro, had developed an impressionist execution independently.51 At the same time Gilman was still painting smoothly blended, tonal pictures, such as the charming domestic interior known as In Sickert’s House, Neuville (Leeds City Art Gallery).52 The wider spread of the use of ‘a clean and solid mosaic of thick paint in a light key’ awaited the capture of new recruits by the Fitzroy Street Group rather than a contagious response within the NEAC.

The expansion of the Fitzroy Street Group 1908–10. The Allied Artists’ Association

The character and composition of the Fitzroy Street Group altered fundamentally in 1908. Without official records it is impossible to distinguish definitively its members (i.e. those who contributed to the rent of 19 Fitzroy Street and who were thus entitled to store and show their pictures there), from the many painters who attended the Saturday gatherings to discuss art and its politics. The future membership of the Camden Town Group provides some clue if we assume that the Camden Towners were primarily selected from regular attenders at Fitzroy Street. Another clue is the inscription of the address ‘19 Fitzroy Street’ on the stretchers of pictures by certain artists, for example Henry Lamb’s Portrait of Edie McNeill: Purple and Gold (private collection).53 The inscription implies that the artists were entitled to use the address professionally but not (as is sometimes assumed) that they lived there. Lamb probably joined Fitzroy Street around 1910. In the intervals between their travels Augustus John, Derwent Lees and James Dickson Innes (who from 1907, when still studying at the Slade, lived nearby in Fitzroy Street) came to the Saturday gatherings, but perhaps as welcome visitors rather than as members. In 1908 Sickert began teaching night classes at the Westminster School of Art and his pupils, such as Malcolm Drummond, became associates of the Fitzroy Street Group. Gore acquired a pupil in 1908, the deaf J. Doman Turner, to whom he gave instruction in the art of drawing by correspondence. However, it may be assumed that Doman Turner, sensitive and talented as his extant watercolours prove, was too shy and retiring often to intrude on the lively gatherings. Gilman met William Ratcliffe, a wallpaper designer, in 1908 and perhaps persuaded him to come to some Saturday meetings although Ratcliffe did not take up painting (by studying part-time at the Slade) until 1910. Some of the original and less progressive members of the Fitzroy Street Group drifted away by 1908 as earlier friendships cooled and divergent interests emerged. William Rothenstein’s attendances may even have ceased in 1907. Walter Russell’s role in Fitzroy Street became weaker. Albert Rothenstein rarely attended after 1908. However, these defections were offset by the new recruits discovered at the first exhibition of the Allied Artists’ Association.

Frank Rutter, then art critic for the Sunday Times and the force behind the creation of the AAA, has detailed its history.54 London lacked a non-jury exhibiting platform of the kind provided in Paris by the Salon des Indépendants. Foreign artists were weary of paying for the transport of their pictures to London only to have them rejected by the various exhibiting societies. They pressed for a subscription organisation which entitled them to exhibit. Native artists also suffered from restrictive selection procedures. Rutter canvassed opinion in London. By Christmas 1907 he had been promised active support from a reasonably wide circle, including Sickert, Gore, Gilman and Lucien Pissarro from the Fitzroy Street Group. Walter Bayes was won over when Rutter disarmingly admitted that the exhibitions would be bigger and worse than the Royal Academy: ‘Why pay a shilling to see two thousand works at the Academy when for the same money you can see four thousand at our exhibition?’ During the winter of 1907–8 Rutter met Jan de Holewinski who had been sent to London to organise an exhibition of Russian arts and crafts. Rutter decided that, like the Paris Salon des Indépendants, a foreign section should be a feature of his creation. They joined forces to look for a location, found and booked the Albert Hall for July 1908, and formally registered the society in February. The name Allied Artists’ Association was chosen for a variety of reasons, including its alphabetical advantages. Sickert took a leading part at the meeting to decide its rules. He pressed for total impartiality, even insisting that the catalogue order should be decided by ballot rather than printed in the alphabetical order used by their Parisian prototype. He made the famous retort to one founder member who thought that the best pictures by the best artists should be hung in the best places: ‘In this society there are no good works or bad works: there are only works by shareholders.’ Every subscriber was entitled to show five works, reduced to three the following year because of the overwhelming response. The 1908 catalogue lists 3,061 works, besides the Russian section; more works were submitted too late for publication. Forty founder members, among them Sickert, were allotted sections to hang. Exhaustion overcame all the supervisors except Sickert who had the sense to superintend from a chair placed in the middle of his section. Rutter, with overall responsibility, covered an enormous mileage round and round the vast hall; the following year he had the happy idea of conducting his operations on a bicycle.

When the exhibition opened, members of the Fitzroy Street Group picked on pictures by two artists in particular. Sickert noticed the work of Walter Bayes who had submitted some decorative panels large enough (and at £157.10 expensive enough) to attract notice whatever the competition. I have been unable to trace any of the pictures Bayes exhibited between 1908 and 1911, but we may infer from his earlier and later work as well as from his idiosyncratic criticism, that they possessed a strong sense of design and possibly an element of humour. It is strange that Sickert and Bayes, both active supporters of the creation of the AAA, did not meet before the exhibition. Moreover, in his art reviews, admittedly published anonymously, Bayes had been singling out Sickert’s work for especial praise since 1906. Rutter, however, reports Sickert’s reaction on first sighting Bayes’s work at the AAA: ‘Who is this man Bayes? His paintings are very good.’ Sickert sought Bayes out and invited him to become a member of Fitzroy Street.

In 1909 it was decided that all members should be eligible to serve on the Hanging Committee of the AAA, and that invitations should be issued on an alphabetical basis. Bayes chaired the committee on which Robert Bevan served. Rutter states that this fortuitous circumstance was responsible for introducing Bevan to the Fitzroy Street Group. However, all other writers, including R.A. Bevan in his Memoir of his father, state that Gore and Gilman spotted Bevan’s pictures at the 1908 AAA show and invited him to join their group in that year.55

Bevan was only five years younger than Sickert. He too had lived and worked abroad. Having trained in Paris, he had visited Pont-Aven in Brittany from 1893–4 and there met, and been influenced by, Gauguin. He also had first-hand knowledge of the work of the earlier generation of impressionists. In 1900 he had settled in London with his wife, the Polish painter, Stanislawa de Karlowska. However, his work remained unknown for another eight years, having only been displayed in two virtually unnoticed one-man shows in a little known gallery in Bayswater. None of the pictures Bevan exhibited at the 1908 AAA can be identified with any certainty. Nevertheless, it is safe to assume that they were strongly coloured poetic landscapes, executed in a broken technique, possibly in the considered divisionist touch which Bevan had recently been developing. A British painter who, isolated from their circle, was capable of such exciting use of colour and handling, was a valuable addition to the Fitzroy Street Group.

The cross-Channel relationships of Fitzroy Street were further strengthened when Charles Ginner entered the group in 1910. Gore is said to have noticed Ginner’s pictures at the 1908 Allied Artists’ exhibition (three illustrations to the work of Edgar Allan Poe, a study of a Head, and a river landscape) but was unable to seek him out since Ginner lived in Paris. Ginner did not exhibit at the AAA in 1909. However, having settled in London by 1910, he not only submitted his work but his surname brought him to serve on the Hanging Committee alongside Gore and Gilman.

Ginner, the French-born son of British parents who lived in Cannes, had trained in Paris and knew the work of the post-impressionists. The Sunlit Wall of 1908 (private collection)56 is one of his few pre-London pictures to survive and betrays, in its thick paint and vivid colour, an immature admiration for van Gogh. Rutter’s recollection, that he answered Gore’s questions about the unknown by saying that ‘his pictures were a nuisance to handle because the paint stood out in lumps and was still wet’, suggests that Ginner came to London with the basis of his life-long style already established. However, the small, tight touch and the strong feeling for pattern which discipline his meticulously observed transcriptions of nature were not fully developed for another year or so. Worms of paint still trail in haphazard fashion across his famous interior of The Café Royal (Tate N05050) first exhibited at the AAA during the summer of 1911. The patterning of this interior is also less emphatic and constructed than in the two Dieppe views, The Sunlit Quay (Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool)57 and Evening, Dieppe (private collection),58 painted later in the year and both exhibited at the second Camden Town Group exhibition in December.

Charles Ginner 1878–1952

A Corner in Chelsea 1910

Oil paint on canvas

965 x 1345 mm

Private collection

© Estate of Charles Ginner

Photo © The Fine Art Society, London / The Bridgeman Art Library

Fig.7

Charles Ginner

A Corner in Chelsea 1910

Private collection

© Estate of Charles Ginner

Photo © The Fine Art Society, London / The Bridgeman Art Library

Harold Gilman 1876–1919

Hampstead Road B.D.V. c.1910–11

Oil paint on canvas

254 x 305 mm

Private collection

Photo © The Fine Art Society, London / The Bridgeman Art Library

Fig.8

Harold Gilman

Hampstead Road B.D.V. c.1910–11

Private collection

Photo © The Fine Art Society, London / The Bridgeman Art Library

A Corner in Chelsea (fig.7), a roofscape of the area of London where Ginner lived when he had first settled in London towards the end of 1909, was among his contributions to the 1910 AAA exhibition. Mrs Dyer, the artist’s sister, recalls that he put a knife through another, a portrait of herself as A Classical Dancer. Ginner’s London landscape suggests he may have been partly responsible for introducing this theme into the vocabulary of Camden Town painting. Whistler and his disciples had painted the Thames and Chelsea, and Sickert had painted his Cumberland Market area during the 1890s. However, although Sickert and Gore painted many landscapes during the period 1906–10, they did so only when away from London, Sickert in Dieppe, and Gore in Dieppe, Yorkshire, Somerset and Hertingfordbury. Gilman, the slowest to develop of this nucleus of Camden Town painters, rarely painted landscape anywhere until 1910–11 (although he had painted a Whistlerian View of the Thames at Hammersmith around 1907).59 Gore occasionally painted Mornington Crescent Gardens from about 1909 onwards but his pictures are idyllic scenes of leisure pursuits with no reference to the houses and tube station just beyond. Gore’s pictures of the architecture of Camden Town, for example Nearing Euston Station (Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge)60 and The Nursery Window, Rowlandson House (private collection),61 mostly date from 1911 (when he spent the entire summer in London) and after. Sickert’s rare paintings and drawings of the urban scene surrounding his studio also date from 1911–12, and almost all were confined to the view from and of his own back garden in Hampstead Road (for example, Tate N05088). Gilman’s first Camden Town landscape, Hampstead Road B.D.V. (fig.8), is also a work of c.1910–11. The fascination that Ginner felt for the London landscape perhaps inspired his Fitzroy Street and Camden Town colleagues to tackle the subject. Certainly the new generation of freshly trained painters to enter the circle during 1910–11, such as Malcolm Drummond62 and William Ratcliffe,63 came to adopt this theme if not to the exclusion of, possibly in preference to, typically Camden Town figures in interiors. Indeed Drummond, with his innate attraction towards strong, tidy patterns running counter to his training by Sickert at the Westminster, must have found Ginner’s example particularly encouraging. The closeness of their relationship is illustrated by Drummond’s remarkable Portrait of Ginner (Southampton City Art Gallery)64 and by Neuville Lane (private collection),65 a little sketch in oil given by Ginner to Drummond.

Ginner was not alone in introducing external scenes of London life into the vocabulary of Camden Town. About 1910 Bevan began to paint his own Swiss Cottage neighbourhood and tackled a series of cabyard subjects, such as The Cab Horse (Tate N05911) and The Cab Yard at Night (Brighton Art Gallery),66 which, together with his pictures of horse sales, became so distinctive a feature of his oeuvre. Bevan, a keen horseman, had often included horses in his landscapes, but it is possible that the belief fundamental to Sickert and his circle, that the painter could find beauty in every aspect of his environment, encouraged him to paint his equine London subjects.

By 1910 the Fitzroy Street Group comprised and welcomed a huge circle of painters. Every progressive artist in London came, with greater or lesser regularity, to the Saturday meetings. The group was composed of a jigsaw of strands based on friendship and professional relationships. Pissarro brought in Manson. Augustus John and Innes may have instigated Henry Lamb’s membership. Sickert’s teaching activities not only brought in Drummond from the Westminster but also, at least as visitors, some of his pupils from the private school (Rowlandson House) he founded in 1910 at 140 Hampstead Road. His star pupil Jean McIntyre67 probably attended, as did Madeline Knox (later Mrs Clifton),68 who, having studied at the Westminster, helped Sickert establish Rowlandson House. However, if we recognise Camden Town painting (the objective record of aspects of urban life in a basically impressionist-derived handling) as a distinct movement in British art, then only a small nucleus of the Fitzroy Street Group may be called Camden Town painters. Gilman was of this number once his American wife had left him, taking their three surviving children back to her native land. He then became an increasingly active force in Fitzroy Street and quickly developed a more broken, colourful and free handling. He also began to paint nude subjects which, in their uninhibited poses and broad, slashed brushwork, represent his most Sickertian productions (fig.9).

Harold Gilman 1876–1919

The Model 1911

457 x 610 mm

Arts Council Collection, Southbank Centre, London

Photo © Arts Council Collection, Southbank Centre, London

Fig.9

Harold Gilman

The Model 1911

Arts Council Collection, Southbank Centre, London

Photo © Arts Council Collection, Southbank Centre, London

Manet and the Post-Impressionists at the Grafton Gallery

In the winter 1910–11 Roger Fry, hitherto known as a mediocre painter, a respected connoisseur of Old Masters, and a brilliant lecturer and critic, staged his exhibition Manet and the Post-Impressionists at the Grafton Gallery. The exhibition and its effects are discussed in almost every survey of British art during this period. All that need be said here of its contents is that Manet served as an introduction to the main body of the show – a large selection of pictures by the most noted French post-impressionists. There were paintings by living artists, including Matisse, Picasso and Vlaminck, but the main emphasis was on the great trio, van Gogh, Cézanne and Gauguin. The visual impact of this exhibition on English artists has perhaps been over-stressed at the expense of proper emphasis on its political consequences. By 1910 there were few progressive painters working in England who were unaware of the French achievements illustrated by Fry’s exhibition. As an assembly of stunning pictures the exhibition undoubtedly confirmed and accelerated the direction in which many of these painters were developing. A few painters, like Gore and Gilman, had never before had such a fine opportunity to study so many aspects of French post-impressionist art. Chronologically the exhibition was well timed to provide the necessary stimulus to the natural evolution of their style and handling.

Ginner was already taking over from Sickert as Gilman’s mentor, and the sight of a fine group of van Gogh’s pictures must have encouraged this change of allegiance. A visit to France in 1911 with Ginner, who acted as his guide around the galleries of Paris, confirmed the new direction in which Gilman’s art was beginning to develop. In Le Pont Tournant (private collection),71 painted while they were both in Dieppe in 1911, Gilman was already groping towards his vision of nature seen in terms of the relationships of pure and brilliant colours. Wyndham Lewis’s report of Gilman’s later rejection of Sickert is no doubt exaggerated, but nonetheless illuminating:

He would look over in the direction of Sickert’s studio, and a slight shudder would convulse him as he thought of the little brown worm of paint that was possibly, even at that moment, wriggling out onto the palette that held no golden chromes, emerald greens, vermilions, only, as it, of course, should do.72

Gore’s reaction to the post-impressionist exhibition was less delayed than Gilman’s. In 1910 his pointilliste application had already begun to give place to a smooth handling. In some of his paintings of 1911 the broad, summary execution is similar to Sickert’s work of about the same date but in others, for example The Artist’s Wife in the Garden of Rowlandson House (private collection),73 he began to group the colours into self-contained areas. Gauguin’s effect on Gore’s vision is more clearly demonstrated in The Balcony of the Alhambra with its strong pattern of flat areas of colour, its slight sense of distortion in the drawing, and its high angled viewpoint. In another tour de force, Gauguins and Connoisseurs at the Stafford Gallery of 1911–12 (private collection),74 showing the gallery during an exhibition of Gauguin’s and Cézanne’s work held in November 1911, subject and treatment were united by Gore in an explicit gesture of homage.

If Fry’s exhibition inspired the younger and less travelled British artists, it held no surprises for such Fitzroy Street members as Bevan, Ginner, Pissarro and Sickert. Sickert lectured on the exhibition at the Grafton Gallery, and wrote the substance of his exuberant criticism in an article for the Fortnightly Review.75 He could not see what all the fuss was about. He had known the work of the artists shown for many years. He then proceeded to treat them neither as gods nor devils, but as ordinary painters subject to successes, failures and external influences just like anyone else. He allowed himself to wonder ‘since “post” is Latin for “after”, where are Bonnard and Vuillard?’ However, Sickert’s attempt to restore a sense of perspective failed. The public, most of the critics, and the figureheads of the art world united to condemn the exhibition as an outrage. The old guard of the NEAC, led by Tonks, Steer and D.S. MacColl, were among the most hostile. It was obvious that the grudging tolerance recently displayed by the NEAC towards Fitzroy Street and its allies would be abruptly withdrawn. In the backlash following the exhibition any young painter not yet firmly established, whose work betrayed non-traditional foreign allegiances, would almost certainly be rejected by the club. This political fact of life was the main impetus behind the creation of the Camden Town Group.

The Camden Town Group

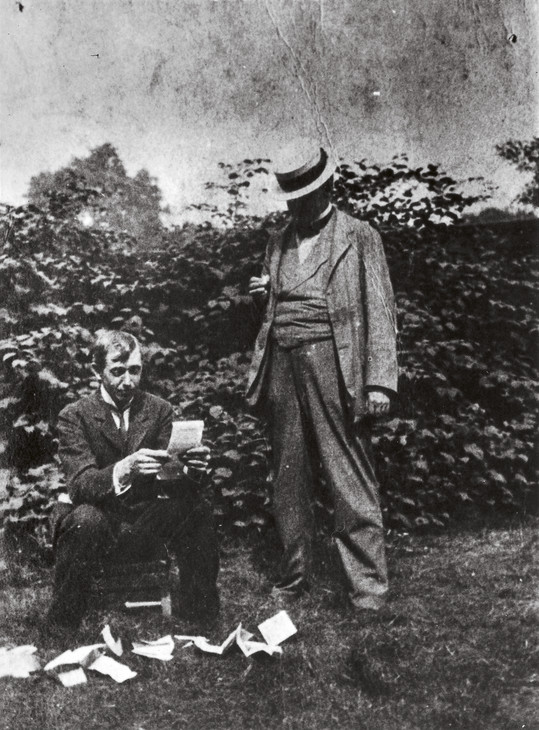

Spencer Gore and Walter Sickert reading press cuttings of the first Camden Town Group exhibition in the garden of Rowlandson House June 1911

Courtesy of Wendy Baron

Fig.10

Spencer Gore and Walter Sickert reading press cuttings of the first Camden Town Group exhibition in the garden of Rowlandson House June 1911

Courtesy of Wendy Baron

Although the reactionary attitude displayed by the controlling faction of the NEAC was the main impetus behind the creation of the Camden Town Group, Ginner recorded another ideal. The Fitzroy Street friends wanted to collect ‘a group which was to hold within a fixed and limited circle those painters whom they considered to be the best and most promising of the day’. Naturally there were arguments as to who these painters were. The proposal to invite Wyndham Lewis caused most dissension, for he was already leaning towards the angular distortions of cubism and his temperament was uncomfortably fiery. Gilman pressed in his favour and won the day. Sickert and Gilman agreed on one key rule: that there should be no woman members. Malcolm Easton has quoted a letter written by Manson to Lucien Pissarro’s wife in answer to her pressing demands that her friend, Diana White, should be elected to the Camden Town Group.78 In his letter Manson explained that the bar against women arose from the ‘disinclination of the Group to include Miss S. and Miss H. of Fitzroy Street in the list of members’. This explanation helped Manson out of a delicate situation vis-à-vis Mrs Pissarro; it probably also reflected his own and Pissarro’s views. Pissarro, indeed, considered that Sickert destroyed the art value of Fitzroy Street by diluting the group ‘in a sea of amateurs and pupils of his’.79 However, Ginner’s accurate factual account gives another reason for the ban on women:

Gilman, strongly supported by Sickert, ... contended that some members might desire, perhaps even under pressure, to bring in their wives or lady friends and this might make things rather uncomfortable between certain of the elect, for these wives or lady friends might not quite come up to the standard aimed at by the group.

Miss Sands and Miss Hudson qualified as neither wife nor mistress. Nevertheless they were excluded. Sickert bluntly explained the situation:

As a matter of fact, as you probably know, the Camden Town Group is a male club, and women are not eligible. There are lots of 2 sex clubs, and several one sex clubs, and this is one of them.

It was left to find a gallery in which to exhibit. Sickert, who had recently held an exhibition at the Carfax Gallery, persuaded Arthur Clifton (who had taken charge of the gallery) to lend them his premises in June.

The Camden Town Group had sixteen members: Bayes, Bevan, Drummond, Gilman, Ginner, Gore, Innes, John, Lamb, Lewis, Lightfoot, Manson, Pissarro, Ratcliffe, Sickert and Doman Turner. It is evident that the originators of the Camden Town Group felt that the best and most promising painters of the day were, on the whole, members of their own Fitzroy Street Group. Lewis and Lightfoot were the only recruits from outside their immediate circle. Following Lightfoot’s resignation and suicide in September, the policy of recruiting from the Friday Club was repeated and Duncan Grant became a member. However, Grant took little part in the group, and sent only one picture, Tulips (Southampton Art Gallery),80 to the second exhibition in December 1911, and nothing at all to the third and last exhibition a year later in December 1912. A fourth exhibition, held at Brighton in the winter of 1913–14, is sometimes labelled as a Camden Town Group exhibition. It was not. It was selected and arranged by the group, but its title was The Work of the English Post-Impressionists, Cubists and Others. It was not a membership exhibition, although many of the exhibitors, while the show was in progress, were in the process of being elected to the London Group. The founder members of the London Group, who thus bypassed the election procedure, were an amalgamation of the Camden Town and Fitzroy Street groups. An incestuous pattern emerges, with Fitzroy Street giving birth to the Camden Town Group and then parent and child jointly siring the London Group.

It is generally claimed that after the December 1912 exhibition Clifton refused to play host to yet another of the Camden Town Group’s financially disastrous shows, thus forcing them to look for alternative premises. The group were then adopted by William Marchant, of the commodious Goupil Gallery, provided they expanded their membership and changed their name. This is the truth, but not the whole truth. At a meeting held in December 1911,81 attended by all the members except Duncan Grant, Innes and John, the idea of increasing the size of the group was first mooted. The Carfax Gallery was too small to allow any enlargement and Gilman, who strongly advocated the advantages of more members, proposed that a new and larger gallery should be found as soon as possible. This motion was carried unanimously, even though a small minority of the members preferred to remain a small and exclusive society. As it happened it took two years to find satisfactory alternative accommodation. However, far from withdrawing his support for the group, Arthur Clifton held a series of exhibitions of its members’ work in 1913: Gore and Gilman had a joint exhibition in January, Sickert in March, Bevan in April, Pissarro in May, and Walter Bayes in October.

The Camden Town Group was even less representative of a particular movement in painting than the Fitzroy Street Group. Drummond and Ratcliffe were broadly aligned with the nucleus of Camden Town painters, Bevan, Gilman, Ginner, Gore and Sickert. However, by 1911 this nucleus was rapidly losing its self-contained identity as each of its members began to explore new stylistic avenues. The heyday of Camden Town painting was over by the time the Camden Town Group was born. Manson and Pissarro were primarily painters of neo-impressionist landscape. The imagery of John, Innes and Henry Lamb was more romantic, and their style, with its fluent draughtsmanship and lyrical sense of colour, totally at variance with those painters who had evolved their handling through impressionism. Walter Bayes’s painting was closer in style and subject matter to this last group. He too painted figures in a landscape, but his approach was cooler, conditioned more by his sense of design than by a subjective response to his subject. Doman Turner as a non-painter in oils, Lewis as an embryonic vorticist, and Lightfoot whose uniquely sensitive revival of the best academic traditions of draughtsmanship and tonal painting defy classification within a twentieth-century context, each stood on his own. Contemporary critics recognised that the group was ‘not a school, but only a convenient name for a number of artists who exhibit together’,82 and that basically what they had in common was ‘the Carfax Gallery in which they exhibit’.83

The support given to the group by such established artists as John and Sickert was largely motivated by their desire to help less renowned colleagues. Gore had counselled against Gilman’s advocacy, and membership of the new society did not entail breaking with the NEAC. Nevertheless, John refrained from exhibiting with the NEAC in the summer of 1911. He also sent two small and informal Welsh landscapes to the Camden Town group.84 His choice may be interpreted as an effort to indicate his support while not outshining less recognised talents. Having made his gesture he did not exhibit again with the group. Sickert did exhibit with the NEAC in the summer of 1911 (as did Bevan, Gore, Lamb and Pissarro). In the first Camden Town Group exhibition he showed a pair of two-figure subjects (one in Kirkcaldy Art Gallery),85 undoubtedly given the Camden Town Murder title for publicity reasons. However, his choice of a Venetian picture of 1903–4, an early Dieppe landscape,86 a very dark and sketchy portrait study,87 and a charming but tiny coster mother and daughter painting to send to the second exhibition,88 may have been deliberately calculated to attract as little press comment as possible away from his fellow members.

On the whole the press reacted favourably, possibly because (as the Observer critic remarked) their nerves had been steeled by ‘recent experiences’.89 The Morning Post, under the title ‘The Camden Wonders’, intended a facetious review but ended up with grave, if somewhat plodding and predictable, assessments of the different artists’ work.90 Nearly all the critics united to disparage Wyndham Lewis’s two pen drawings, both entitled The Architect,91 the first works Lewis had exhibited in London since the NEAC of 1904. In the next two exhibitions Lewis remained the chief thorn to reviewers. Otherwise the Camden Town Group was accepted as a band of ‘intensely serious artists who ... show neither eccentricity nor a desire to épater le bourgeois, but are clearly inspired by the longing for self-expression in what each considers the most suitable language’.92

The Camden Town Group is now chiefly remembered as the forcing house of the much larger, and much longer lasting, London Group. It also brought about the alliance of Gilman and Ginner to propound their doctrine of Neo-Realism, a development just outside the scope of this essay, as is the Cumberland Market Group founded by Gilman, Ginner and Bevan. Both factionalism and expansionism were inevitable given the diverse talents and temperaments of the sixteen members of the group. Nevertheless, the Camden Town Group did not just create the opportunity for new beginnings: it was the culmination of Sickert’s ambition to create an ambience in London wherein young painters could encourage each other towards independence and professional self-confidence.

Notes

Sickert’s painting was destroyed. Steer’s is in a private collection (reproduced in the catalogue of a sale at Sotheby’s, London, 21 July 2005, lot 19).

Walter Sickert, ‘Impressionism’, in A Collection of Paintings by the London Impressionists, exhibition catalogue, Goupil Gallery, London 1889, in Anna Gruetzner Robins (ed.), Walter Sickert: The Complete Writings on Art, Oxford 2000, p.60.

Sickert’s letters to Ethel Sands and Nan Hudson were inherited by Christopher Sands who lent them to me (as Miss Sands herself had done when I met her in 1959). These and all the other letters lent to me by Christopher Sands written by their many friends to Miss Sands, to her mother Mrs Mahlon Sands and to Miss Hudson, were the basis of my book Miss Ethel Sands and her Circle, London 1975. In 1976 (and in my later writings) I used my own copies of the letters. The original letters subsequently entered the Tate Archive.

Prime version reproduced in Wendy Baron, Sickert: Paintings and Drawings, New Haven and London 2006, no.97 with details of the other versions given in the catalogue text. Anna Gruetzner Robins has established that Sickert painted Minnie Cunningham (Tate T02039) in 1892; see ‘Sickert “Painter-in-Ordinary” to the Music-Hall’, in Wendy Baron and Richard Shone (eds.), Sickert: Paintings, exhibition catalogue, Royal Academy, London 1992, pp.13–24.

Frederick Gore, ‘Spencer Gore: A Memoir by his Son’, in Spencer Frederick Gore 1878–1914, exhibition catalogue, Anthony d’Offay Gallery, London 1974.

A scene from The Duel in the Snow, performed at the Empire Music Hall. In 1976 I did not know of this painting and mistakenly identified another early music hall painting by Gore as The Mad Pierrot Ballet. I have corrected that passage here. In fact, ‘The Mad Pierrot’ Ballet at the Alhambra (private collection, Australia), is a work of 1911 and was exhibited with the Camden Town Group in December of that year. It is reproduced in Wendy Baron, Perfect Moderns: A History of the Camden Town Group, Aldershot and Vermont 2000, no.20.

Reproduced in Modern Painters: The Camden Town Group, exhibition catalogue, Tate Britain, London 2008 (19).

Juxtaposed reproductions in Baron 1979, nos.8 and 9. Behind the Blind (private collection) is also reproduced in the sale catalogue at Christie’s, King Street, London, 7 March 1986, lot 220. Sickert’s Mornington Crescent Nude: Contre-Jour is also reproduced in Baron 2006, no.248.

For example, View of Dieppe; reproduced in Baron 1979, no.11 and in Lucien Pissarro et le post-impressionisme anglais, exhibition catalogue, Musée de Pontoise 1998 (75).

Thomson was never an active member of the Fitzroy Street Group and probably soon resigned. He settled in France in 1914.

Louis F. Fergusson, ‘Harold Gilman’, in Wyndham Lewis and Louis F. Fergusson, Harold Gilman: An Appreciation, London 1919, p.19.

Walter Sickert, ‘The New Life of Whistler’, Fortnightly Review, December 1908, in Robins (ed.) 2000, p.185.

Phrases taken from Walter Sickert, ‘A Critical Calendar’, English Review, March 1912, in Robins (ed.) 2000, pp.298–303.

For example, Girl Dressing (Southampton City Art Gallery); reproduced at http://www.bridgemanart.com .

Walter Sickert, ‘The Futurist “Devil among the Tailors”’, English Review, April 1912, in Robins (ed.) 2000, p.307.

Letter to Quentin Bell written in 1954. I am indebted to Professor Bell for giving me a copy of Miss Sands’s letter.

Great Western Railway, Acton 1907 (Government Art Collection), reproduced in Baron 2000, no.34; Well Farm Bridge, Acton 1907 (Leeds City Art Gallery) reproduced in Baron 1979, no.100; and Shunting Acton 1908 (private collection) reproduced in Baron 1979, no.30. All three paintings are reproduced in Anne Thorold, A Catalogue of the Oil Paintings of Lucien Pissarro, London 1983, nos.118, 120 and 125 respectively.

For example, Yorkshire Landscape with Cottages (private collection); reproduced in Baron 1979, no.32.

Also known as Girl in a Flowered Hat but first exhibited at the NEAC in spring 1908 as Some-one waits. Reproduced in Baron 1979, no.33, Baron 2000, no.28 and Tate Britain 2008 (35).

The two most realised versions are Girl at a Window, Little Rachel (Tate T06447) and Little Rachel at a Mirror (Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge) reproduced in Baron 2006, no.338. All known versions are catalogued and some reproduced in Baron 2006, nos.337–41 inclusive.

Catalogued and some reproduced in Baron 2006, nos.332–6 inclusive. Mornington Crescent Nude in the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge is reproduced in Tate Britain 2008 (60); the contre-jour painting in the Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide, and another nude in this setting (private collection) are reproduced in Royal Academy 1992 (65) and fig.145 respectively. The latter is also reproduced in Baron 2006, no.332.

For example, Summer’s Day, Douelan, Brittany 1907; reproduced in Francis Farmar (ed.), The Painters of Camden Town 1905–1920, exhibition catalogue, Christie’s, London 1988 (34) and in the catalogue of a sale at Christie’s, South Kensington, London, 6 September 2001, lot 77.

Frank Rutter, Since I was Twenty-Five, London 1927. This book is the source for the following summary and quotations.

Reproduced in Tate Britain 2008 (70). This view shows Ampthill (now demolished) crossing the railway lines where they bifurcate just before the approach to Euston.

Examples in public collections painted around 1912, besides the ever popular and often exhibited St James’s Park (Southampton Art Gallery), which is reproduced in Baron 1979, p.47, Baron 2000, no.17 and Tate Britain 2008 (23), include: A Chelsea Street (Ashmolean Museum, Oxford) reproduced in Christie’s 1988 (117); Hammersmith Bridge (Huddersfield Art Gallery); and Queen Anne’s Mansions: London Flats (Plymouth City Art Gallery) reproduced in Baron 1979, no.139.

Besides the two versions of Clarence Gardens mentioned above, Ratcliffe painted several views of Hampstead Garden Suburb, including one from Willifield Way where he lived (Tate T12260).

Jean Douglas McIntyre (1889–1967) studied in Sickert’s class at the Westminster School of Art from around 1908–10 and was a founder-pupil at his private school at 140 Hampstead Road. She married A.E.D. Anderson in 1915. Her sister Lesley married William (later Earl) Jowitt in 1913. The Andersons and the Jowitts were discerning patrons of contemporary art and owned distinguished collections of work by Sickert. A painting of Cumberland Market by McIntyre is reproduced in Christie’s 1988 (109).

Madeline Knox (1890–1975), who was painted by Gilman (Tate T13024), visited Canada from c.1911–13. On her return she met Arthur Clifton of the Carfax Gallery who, in 1916, held a sell-out exhibition of her work. They later married and, in 1925, settled in Kent. She gave up painting and drawing and took up embroidery. Her work in this medium includes the altar frontal in the Behrend Stanley Spencer Chapel at Burghclere.

Possibly the painting reproduced in Gail Engert, Maxwell Gordon Lightfoot, exhibition catalogue, Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool 1972 (17).

Reproduced in Frederick Gore and Richard Shone, Spencer Frederick Gore, exhibition catalogue, Anthony d’Offay Gallery, London 1983 (17).

Walter Sickert, ‘Post-Impressionists’, Fortnightly Review, January 1911, in Robins (ed.) 2000, pp.272–81.

Charles Ginner, ‘The Camden Town Group’, Studio, November 1945. This article, the fullest factual firsthand account of the birth of the group, is the main source for the following summary and quotations.

Malcolm Easton, ‘“Camden Town” into “London”: Some Intimate Glimpses of the Transition and its Artists 1911–1914’, appendix in Art in Britain 1890–1940, exhibition catalogue, University of Hull 1967, p.66.

Ibid. p.68, letter to Pissarro to Manson quoted by Dr Easton. The letter (of December 1913) is in the Ashmolean Museum.

Louie, a dark and sketchy bust portrait of a coster girl painted c.1906 (private collection) has not been reproduced.

Mother and Daughter (private collection); reproduced in Lillian Browse, Sickert, London 1960, pl.64, Baron 2006, no.368 and in catalogue of sale at Christie’s, London, 8 June 2007, lot 43.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to The Fine Art Society for their permission to reprint this essay, first published as the introduction to a loan exhibition researched, selected and catalogued by Wendy Baron for The Fine Art Society in 1976. Some minor corrections of fact have been made by the author in the light of subsequent research.

We are grateful to The Fine Art Society for their permission to reprint this essay, first published as the introduction to a loan exhibition researched, selected and catalogued by Wendy Baron for The Fine Art Society in 1976. Some minor corrections of fact have been made by the author in the light of subsequent research.

Wendy Baron is an independent scholar and former Director of the Government Art Collection. She is the author of numerous texts on Walter Sickert and the Camden Town Group.

How to cite

Wendy Baron, ‘Camden Town Recalled’, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://www