Harold Gilman Madeleine Knox c.1910-1

Harold Gilman,

Madeleine Knox

c.1910-1

Although ostensibly a portrait of the artist Madeline Knox, the relaxed pose and introspective gaze of the solitary female figure standing in a domestic interior gives this work an intimate atmosphere. Articulated in loose, expressive brushstrokes, the light greens, yellows and creams of the wallpaper contrast with the golds, reds and browns of the figure’s clothing.

Harold Gilman 1876–1919

Madeline Knox

c.1910–11

Oil paint on canvas

608 x 454 mm

Inscribed by the artist ‘H. Gilman’ bottom right

Accepted by HM Government in lieu of inheritance tax and allocated to Tate 2010

T13024

c.1910–11

Oil paint on canvas

608 x 454 mm

Inscribed by the artist ‘H. Gilman’ bottom right

Accepted by HM Government in lieu of inheritance tax and allocated to Tate 2010

T13024

Ownership history

Given by the artist to Robert Bevan (1865–1925); by descent to the artist’s son, Robert Alexander Bevan (1901–1974), and thence by descent to his wife Natalie (1909–2007); accepted by HM Government in lieu of inheritance tax and allocated to Tate 2010.f

Exhibition history

1934

Paintings by Harold Gilman 1876–1919, Arthur Tooth & Sons, London, September–October 1934 (32, as ‘Interior with Standing Figure’).

1940

British Painting Since Whistler, National Gallery, London, March–August 1940 (130, as ‘Woman standing in interior’).

1954–5

Harold Gilman 1876–1919, (Arts Council tour), Arts Council, London, January–December 1954, Manchester Art Gallery, November–December 1954, Tate Gallery, London, May–June 1955 (14, as ‘Portrait of Margaret Knox’).

1961

Camden Town Group Fiftieth Anniversary Exhibition, The Minories, Colchester, September 1961 (13, as ‘Madeline Knox (Mrs. Arthur Clifton)’).

1967

The Camden Town Group & English Painting 1900–1930’s, William Ware Gallery, London, March 1967 (36, as ‘Madeleine Knox’).

1969

Harold Gilman 1876–1919: An English Post-Impressionist, The Minories, Colchester, March 1969, Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, April–May 1969, Graves Art Gallery, Sheffield, May–June 1969 (18, as ‘Margaret Knox’).

1975

English Paintings from the Bevan Collection, Anthony d’Offay Gallery, London, April–May 1975 (11, reproduced).

1975

The R.A. Bevan Collection from Boxted House, The Minories, Colchester, July–August 1975 (61).

2008–10

From Sickert to Gertler: Modern British Art from Boxted House, Gainsborough’s House, Sudbury, October–December 2008, Brighton Art Gallery and Museums, April–September 2010 (21, as ‘Madeleine Knox’, reproduced).

References

1979

Wendy Baron, The Camden Town Group, London 1979, no.24, reproduced p.139.

1981

Andrew Causey and Richard Thomson (eds.), Harold Gilman 1876–1919, exhibition catalogue, Arts Council, London 1981, nos.18, 22.

1992

Wendy Baron and Richard Shone (eds.), Sickert: Paintings, exhibition catalogue, Royal Academy, London 1992, fig.50, reproduced.

2008

Frances Stenlake, Robert Bevan: From Gauguin to Camden Town, London 2008, p.84.

Technique and condition

Madeline Knox is painted in artists’ oil paints on a single piece of simple plain-weave linen. The off-white priming was applied commercially as it extends to the cut edges of the support. The primed canvas is attached to its accessory support with ferrous tacks, now rusted. As there are no other holes visible in the tacking margin it can be assumed that this is the original stretcher and attachment.

The initial sketch was done in dark blue diluted oil paint and, although most of the contours are now covered, there are glimpses of a sketchy outline to the left of the figure’s skirt. The architectural structure, which seems to have been laid-in first, is a less modelled and impastoed part of the painting. Elsewhere, the paint was applied thickly with only a little addition of thinners or painting medium, and therefore each brushstroke remains distinct. The coat and dress are laid-in with thick impasto in a rich red with traces of yellow, blue and green visible under magnification. Compared to the face they were painted more flowingly with longer, more sweeping brushstrokes. The face seems to have a yellow and green underlay in the shadows, with a full palette of bright colours in the upper layers, including rose madder (as seen in ultra-violet light). The colours are applied wet-in-wet, with a smaller brush leaving stiffer peaks of paint. The background is painted up to and over the edges of the figure. Some areas of priming are left exposed, especially in the background and the lower parts of the dress.

It is probable that the painting was originally unvarnished, as there appears to be dirt beneath the varnish gathered into the crevices of the textured paint. The thick, glossy, yellowed natural resin varnish that had pooled in the crevices of the impasto all over the surface was removed by Tate conservators.

Annette King

September 2004

How to cite

Annette King, 'Technique and Condition', September 2004, in Helena Bonett, ‘Madeline Knox c.1910–11 by Harold Gilman’, catalogue entry, December 2010, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://wwwEntry

Description

In this painting a young woman stands by a stone fireplace with her head lowered, absent-mindedly fingering her coat. Above the mantelpiece is a large but cropped gilt-framed mirror that reveals very little from its dark reflection; the gold is echoed in the buttons that punctuate the dark expanse of the woman’s jacket and dress. The complementary colours of green and red dominate the painting, with the red-brown of the figure’s clothing contrasting with the predominantly cream-green colours of the wallpaper. A strong light casts a dark shadow on to the fireplace and wallpaper immediately behind the figure.

Although ostensibly a portrait, there are few clues about the woman’s character or background. The setting is ambiguous: is this a living room or a bedroom (the piece of furniture to the left of the figure could be a sofa or a bed)? Although the mood of the painting is calm and introspective, the figure is also wearing a jacket and shoes: is she about to leave the room or has she just returned?

Women in interiors

When first exhibited in 1934 this painting was entitled Interior with Standing Figure (it was not to be identified as a portrait of Madeline Knox until the 1950s). Gilman depicted lone women in interiors throughout his career; see, for example, such early works as Edwardian Interior c.1907 (Tate T00096, fig.1), French Interior c.1907 (Tate N05783) and Lady on a Sofa c.1910 (Tate N05831), and, later, Head of a Girl c.1911 (fig.2), The Coral Necklace 1914 (fig.3) and Girl with a Teacup c.1914–15 (private collection).1 In Girl by a Mantelpiece 1914 (Potteries Museum and Art Gallery, Stoke-on-Trent),2 a young girl stands next to the same fireplace; the glass ornament behind her could be the same as the object that sits on the mantelpiece behind Madeline Knox in Tate’s painting.

Harold Gilman 1876–1919

Edwardian Interior c.1907

Oil paint on canvas

support: 533 x 540 mm

Tate T00096

Presented by the Trustees of the Chantrey Bequest 1956

Fig.1

Harold Gilman

Edwardian Interior c.1907

Tate T00096

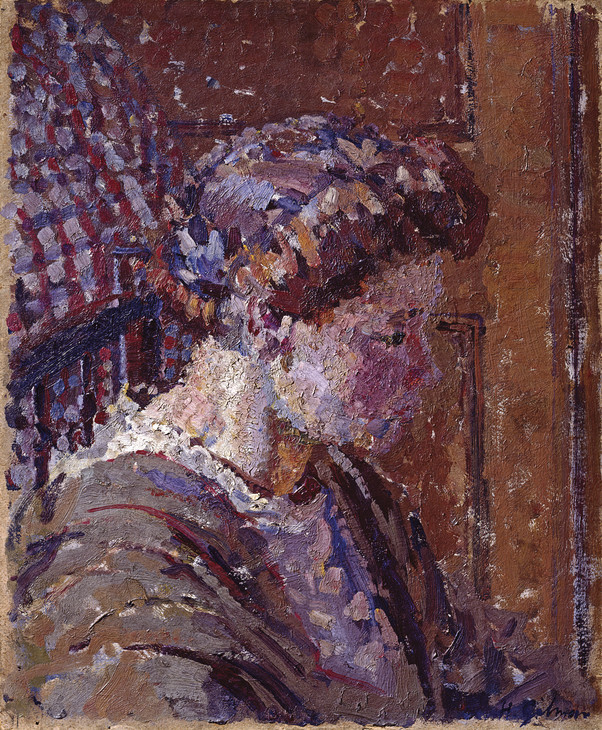

Harold Gilman 1876–1919

Head of a Girl c.1911

Oil paint on board

375 x 310 mm

Private collection

Photo © Tate

Fig.2

Harold Gilman

Head of a Girl c.1911

Private collection

Photo © Tate

Harold Gilman 1876–1919

The Coral Necklace 1914

Oil paint on canvas

600 x 450 mm

Royal Pavilion and Museum, Brighton and Hove

Reproduced with the kind permission of The Royal Pavilion and Museums (Brighton & Hove)

Fig.3

Harold Gilman

The Coral Necklace 1914

Royal Pavilion and Museum, Brighton and Hove

Reproduced with the kind permission of The Royal Pavilion and Museums (Brighton & Hove)

Harold Gilman 1876–1919

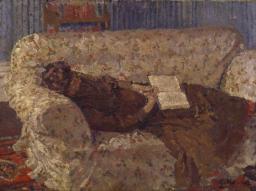

Meditation 1910–11

Oil paint on canvas

620 x 465 mm

Leicester Arts and Museums Service

Photo © Leicester Arts and Museums Service

Fig.4

Harold Gilman

Meditation 1910–11

Leicester Arts and Museums Service

Photo © Leicester Arts and Museums Service

Madeline Knox relates to another work by Gilman of the same period, Meditation 1910–11 (fig.4). Indeed, the art historian Wendy Baron has suggested that both works may depict Knox,3 the figures appearing to have similar hairstyles and facial characteristics. However, Tate cataloguer Nicola Moorby has stated that the figure in Meditation is thought to be Gilman’s neighbour in Letchworth, Signe Parker.4 Contemporary photographs of Knox and Parker reveal that the two women looked quite different, Knox being smaller and with a more slender face, confirming that Meditation is a portrait of Parker rather than Knox (figs.5 and 6). Nevertheless, the two paintings have a similar composition, presenting full-length views of women in domestic interiors with dark shadows cast on the wall behind them. Although the mood of Meditation is rather more sombre, both have an introspective atmosphere.

Madeline Knox with a Boxer Dog Early 1900s

Photograph on paper (photographer unknown)

Tate Archive TGA 8721/30

Fig.5

Madeline Knox with a Boxer Dog Early 1900s

Tate Archive TGA 8721/30

Signe Parker sitting in her house at 102 Wilbury Road, Letchworth Garden City c.1910

First Garden City Heritage Museum

Photo © First Garden City Heritage Museum

Fig.6

Signe Parker sitting in her house at 102 Wilbury Road, Letchworth Garden City c.1910

First Garden City Heritage Museum

Photo © First Garden City Heritage Museum

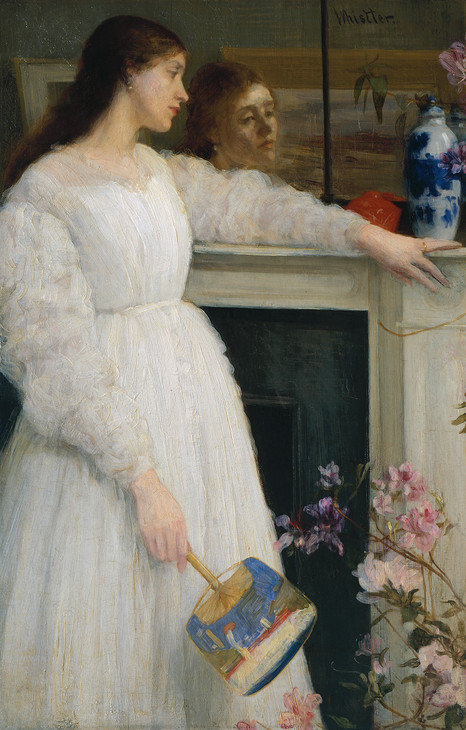

In his introduction to the 1913 Post-Impressionist and Futurist Exhibition, the curator and critic Frank Rutter described Gilman, Spencer Gore and Charles Ginner as the ‘“intimists” of England’, likening them to the French painters Pierre Bonnard and Edouard Vuillard who often depicted women in highly decorated, middle class interiors.5 But many other artists in Britain also focused on this theme in the period. Following the example of James Abbott McNeill Whistler and works such as his Symphony in White, No.2: The Little White Girl 1864 (Tate N03418), William Rothenstein, William Orpen and Ambrose McEvoy regularly exhibited paintings of figures in interiors at the New English Art Club (figs.7–9). Gwen John, who like Gilman was a graduate from the Slade, also painted solitary female figures in interior scenes (see, for example, her Chloë Boughton-Leigh 1904–8, Tate N04088 fig.10, shown at the New English Art Club in 1908).

James Abbott McNeill Whistler 1834–1903

Symphony in White, No. 2: The Little White Girl 1864

Oil on canvas

support: 765 x 511 mm; frame: 1085 x 830 x 118 mm

Tate N03418

Bequeathed by Arthur Studd 1919

Fig.7

James Abbott McNeill Whistler

Symphony in White, No. 2: The Little White Girl 1864

Tate N03418

Sir William Rothenstein 1872–1945

Miss Edith Lockyer Williams 1893

Oil on canvas

support: 1232 x 597 mm

Tate N05407

Presented by Professor Basil Williams 1943

© The estate of Sir William Rothenstein. All Rights Reserved 2010 / Bridgeman Art Library

Fig.8

Sir William Rothenstein

Miss Edith Lockyer Williams 1893

Tate N05407

© The estate of Sir William Rothenstein. All Rights Reserved 2010 / Bridgeman Art Library

Sir William Orpen 1878–1931

The Mirror 1900

Oil on canvas

support: 508 x 406 mm; frame: 682 x 580 x 75 mm

Tate N02940

Presented by Mrs Coutts Michie through the Art Fund in memory of the George McCulloch Collection 1913

Fig.9

Sir William Orpen

The Mirror 1900

Tate N02940

Gwen John 1876–1939

Chloë Boughton-Leigh 1904–8

Oil on canvas

support: 584 x 381 mm

Tate N04088

Purchased 1925

Fig.10

Gwen John

Chloë Boughton-Leigh 1904–8

Tate N04088

Vilhelm Hammershoi 1864–1916

Interior 1899

Oil on canvas

support: 645 x 581 mm; frame: 725 x 660 x 63 mm

Tate N04106

Presented in memory of Leonard Borwick by his friends through the Art Fund 1926

Fig.11

Vilhelm Hammershoi

Interior 1899

Tate N04106

Madeline Knox

Knox was brought up in Grantham in Lincolnshire and moved to London in 1906, briefly studying at the Lambeth School of Art.10 She went on to study at the Westminster School of Art in Vincent Square from 1907 to 1910, where she trained under Sickert for her final two years. In 1909 she joined his etching class, and later that year helped him to set up an etching school at 209 Hampstead Road. When it moved to 140 Hampstead Road the school was named Rowlandson House, and painting and drawing were also taught (see Tate N05088). Sickert’s many commitments at this time made him ill, however, which meant that Knox was left in charge of the school. This, in turn, made her ill, leading her to leave the school in late 1910. Sickert wrote to his friends Ethel Sands and Nan Hudson:

By the mercy of providence the new McColl society [Contemporary Art Society] (which I have done nothing but abuse) have heaped coals of fire on my head & bought George Moore’s portrait.11 I do not yet know for how much. In any case that will enable me to give Miss Knox her money out in one or two payments. I am grieved at her breakdown & of course reproach myself with allowing her to do so much. But she had the deceptive pluck of the spirited young, who look upon a suggestion that anything is too much for their strength as almost a rejection. The thing however having happened, it will be a relief to me henceforth to be risking no one else’s money. I couldn’t foresee my illness or of course I should not have dreamt of the partnership.12

Around 1911 Knox travelled to Canada where she lived until 1914–15 (which confirms that this painting was made no later than 1911).13 Upon returning to London, she met Arthur Clifton (1863–1932) who ran the Carfax Gallery where the Camden Town Group had held their three exhibitions in 1911 and 1912.14 The two later married.

Knox exhibited with the New English Art Club in 1915 and held a successful solo show at the Carfax in October 1916, Watercolour Drawings by Madeline Knox, in which all the works were sold. Reviews were extremely positive. The critic of the Morning Post wrote:

Miss Knox depends entirely on clarity of vision and a natural instinct for the pictorial, and these gifts, combined with direct incisive drawing, enable her to suggest in remarkable fashion the infinite details of a landscape, its subtle nuances of light and shade and colour.15

An unidentified press cutting shows another critic responding favourably:

Hitherto this artist’s name has been almost unknown outside the circle of Mr Walter Sickert, at whose school she was a student a few years ago. But her drawings on view at the Carfax Gallery are of such merit and individuality that the lady will surely make a mark.16

For the reviewer Sir Claude Phillips, writing in the Daily Telegraph:

This artist divides her energies between still-life and landscape, painting already with certainty and concision, and affecting invariably light, yet not bright or stimulating colour-schemes.17

Knox later held an Exhibition of Watercolour Drawings of Sussex, Perigord, and the Pyrenées Orientales at the Twenty One Gallery in London in November 1924. In 1925 she settled in Mersham in Kent where she gave up painting and drawing in favour of embroidery. She was commissioned in the 1930s by Mr and Mrs J.L. Behrend to embroider the altar frontal for the Sandham Memorial Chapel in Burghclere, Hampshire, where Stanley Spencer’s famous large-scale paintings can be found. Using fine natural linen embroidered with linen thread and green and gold silk thread, she created the frontal using colours to complement Spencer’s Resurrection of the Soldiers, on the wall behind the altar.18

Ownership

It is generally thought that Gilman presented this painting as a gift to his fellow Camden Town Group member Robert Bevan, probably around the time of its execution. In her 2008 study of Bevan, however, Frances Stenlake states that Bevan bought it from his friend in about 1910.19 It was inherited by the artist’s son, Robert A. Bevan, who hung it in his home Boxted House in Boxted, Essex.

Helena Bonett

December 2010

Notes

Reproduced in Wendy Baron, Perfect Moderns: A History of the Camden Town Group, Aldershot and Vermont 2000, no.5, and Modern Painters: The Camden Town Group, exhibition catalogue, Tate Britain, London 2008 (53).

Reproduced at Bridgeman Art Library, http://www.bridgemanart.com/image/Gilman-Harold-1876-1919/Girl-by-a-Mantelpiece/6bdf6758479e48ac9285c41ea53ba048?key=girl%20by%20a%20mantelpiece%20gilman&filter=CBPOIHV&thumb=x150&num=15&page=1 , accessed 1 December 2010.

Wendy Baron, The Camden Town Group, London 1979, p.138. Baron notes that Study c.1910 also depicts Knox; reproduced at the National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, http://www.ngv.vic.gov.au/col/work/3980 , accessed 1 December 2010.

Frank Rutter, ‘Foreword’, in Post-Impressionist and Futurist Exhibition, exhibition catalogue, Doré Galleries, London 1913, [p.2].

Louis F. Fergusson, ‘Harold Gilman’, in Wyndham Lewis and Louis F. Fergusson, Harold Gilman: An Appreciation, London 1919, p.28.

Gilman painted Gore on a number of occasions. See, for instance, the c.1911–12 portrait in the National Portrait Gallery, London, http://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/largerimage.php?firstRun=true&sText=Spencer+Gore+gilman&search=sp&rNo=0 , accessed 28 January 2011.

Gilman painted Karlowska on a number of occasions. See, for example, the c.1913 portrait in the National Portrait Gallery, London, http://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/largerimage.php?firstRun=true&sText=karlowska+gilman&search=sp&rNo=0 , accessed 28 January 2011.

Biographical information on Knox is from Wendy Baron, Camden Town Recalled, exhibition catalogue, Fine Art Society, London 1976, pp.35–6, Baron 1979, p.138, and Tate N05088.

Walter Sickert, letter to Nan Hudson and Ethel Sands, [December 1910], Tate Archive TGA 9125/5, no.75.

Clifton and Sickert fell out over Clifton’s affair with Knox. See Matthew Sturgis, Walter Sickert: A Life, London 2005, pp.502–3.

‘Art Exhibitions’, Morning Post, 30 October 1916. Press cutting inside Knox’s exhibition catalogue in Tate Archive, TGA 8721/26.

‘The Drawing Room. Fine Art. Water-colour Drawings by Miss Madeline Knox’, publication unknown. Press cutting inside Knox’s exhibition catalogue in Tate Archive, TGA 8721/26.

Related biographies

Related essays

Related catalogue entries

Related reviews and articles

- Louis F. Fergusson, ‘Harold Gilman’ in Wyndham Lewis and Louis F. Fergusson, Harold Gilman: An Appreciation, London: Chatto & Windus 1919, pp.19–32.

How to cite

Helena Bonett, ‘Madeline Knox c.1910–11 by Harold Gilman’, catalogue entry, December 2010, in Helena Bonett, Ysanne Holt, Jennifer Mundy (eds.), The Camden Town Group in Context, Tate Research Publication, May 2012, https://www