Henry Moore OM, CH Working Model for Three Piece No.3: Vertebrae 1968, cast c.1968

Image 1 of 13

-

Henry Moore OM, CH, Working Model for Three Piece No.3: Vertebrae 1968, cast c.1968© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Working Model for Three Piece No.3: Vertebrae 1968, cast c.1968© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Working Model for Three Piece No.3: Vertebrae 1968, cast c.1968© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Working Model for Three Piece No.3: Vertebrae 1968, cast c.1968© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Working Model for Three Piece No.3: Vertebrae 1968, cast c.1968© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Working Model for Three Piece No.3: Vertebrae 1968, cast c.1968© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Working Model for Three Piece No.3: Vertebrae 1968, cast c.1968© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Working Model for Three Piece No.3: Vertebrae 1968, cast c.1968© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Working Model for Three Piece No.3: Vertebrae 1968, cast c.1968© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Working Model for Three Piece No.3: Vertebrae 1968, cast c.1968© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Working Model for Three Piece No.3: Vertebrae 1968, cast c.1968© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Working Model for Three Piece No.3: Vertebrae 1968, cast c.1968© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Working Model for Three Piece No.3: Vertebrae 1968, cast c.1968© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Working Model for Three Piece No.3: Vertebrae 1968, cast c.1968© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Working Model for Three Piece No.3: Vertebrae 1968, cast c.1968© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Working Model for Three Piece No.3: Vertebrae 1968, cast c.1968© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Working Model for Three Piece No.3: Vertebrae 1968, cast c.1968© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Working Model for Three Piece No.3: Vertebrae 1968, cast c.1968© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Working Model for Three Piece No.3: Vertebrae 1968, cast c.1968© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Working Model for Three Piece No.3: Vertebrae 1968, cast c.1968© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Working Model for Three Piece No.3: Vertebrae 1968, cast c.1968© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Working Model for Three Piece No.3: Vertebrae 1968, cast c.1968© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Working Model for Three Piece No.3: Vertebrae 1968, cast c.1968© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Working Model for Three Piece No.3: Vertebrae 1968, cast c.1968© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Working Model for Three Piece No.3: Vertebrae 1968, cast c.1968© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Working Model for Three Piece No.3: Vertebrae 1968, cast c.1968© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH,

Working Model for Three Piece No.3: Vertebrae

1968, cast c.1968

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

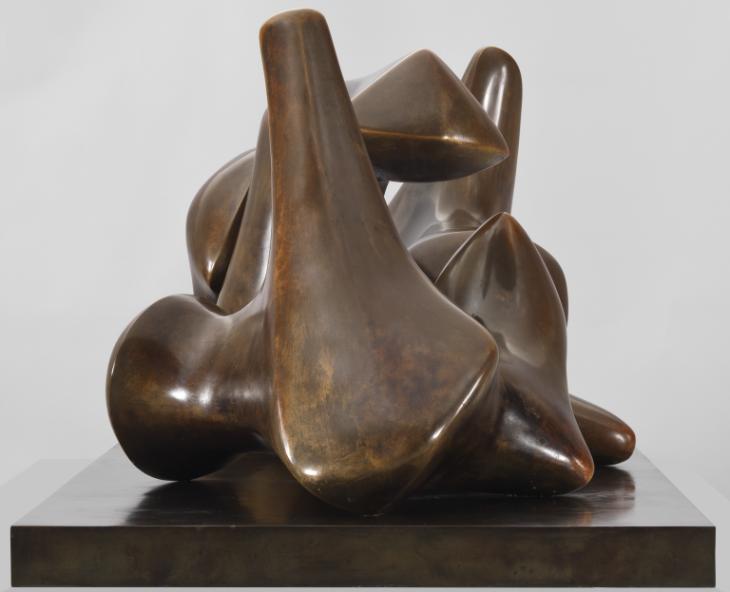

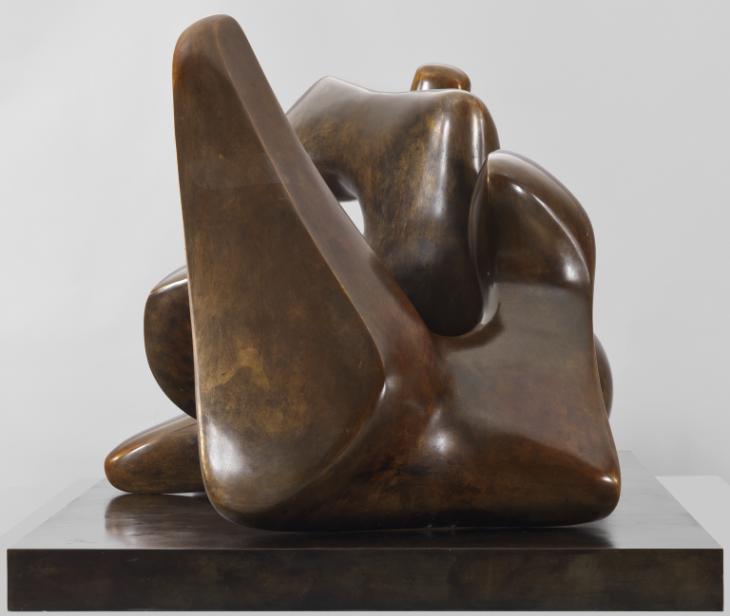

Working Model for Three Piece No.3: Vertebrae is made up of three similar, bone-like forms that interlock in a rhythmic horizontal arrangement. Made in 1968, the sculpture developed from Moore’s earlier multi-part figurative sculptures, but in this work overt references to the human figure are superseded by a focus on organic interconnectivity, manifested by sockets and joints.

Henry Moore OM, CH 1898–1986

Working Model for Three Piece No.3: Vertebrae

1968, cast c.1968

Bronze

940 x 2363 x 1220 mm

Inscribed ‘Moore 0/8’ and ‘H. NOACK BERLIN’ on base

Presented by the artist 1978

Artist’s copy aside from edition of 8

T02303

Working Model for Three Piece No.3: Vertebrae

1968, cast c.1968

Bronze

940 x 2363 x 1220 mm

Inscribed ‘Moore 0/8’ and ‘H. NOACK BERLIN’ on base

Presented by the artist 1978

Artist’s copy aside from edition of 8

T02303

Ownership history

Presented by the artist to Tate in 1978 as part of the Henry Moore Gift.

Exhibition history

1968

Henry Moore, Tate Gallery, London, July–September 1968, no.142.

1970

Henry Moore: Bronzes 1961–70, Marlborough Gallery, New York, April–May 1970, no.31.

1971

Henry Moore 1961–1971, Staatsgalerie Moderner Kunst, Munich, October–November 1971, no.24.

1975

Henry Moore: Fem Decennier, Skulptur, Teckning, Grafik 1923–1975, British Council touring exhibition: Henie-Onstad Kunstsenter, Oslo, June–July 1975; Kulturhuset, Stockholm, August–October 1975; Nordjyllands Kunstmuseum, Aalborg, October–November 1975, no.77.

1976

The Work of the British Sculptor Henry Moore, Zürcher Forum, Zürich, June–August 1976, no.88.

1978

Henry Moore: 80th Birthday Exhibition, Cartwright Hall, Bradford, April–June 1978, no.14.

1978

The Henry Moore Gift, Tate Gallery, London, June–August 1978, no number.

1981

Henry Moore: Sculptures, Drawings, Graphics 1921–1981, Palacio de Velázquez, Palacio de Cristal, Parque de El Retiro, Madrid, May–August 1981, no.68.

1981

Henry Moore, Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian, Lisbon, September–November 1981, no.107.

1981–2

Henry Moore: Exposició Retrospectiva, Escultures, Dibuixos i Gravats 1921–1981, Fundació Joan Miró, Barcelona, December 1981–January 1982, no.66.

1982–3

Henry Moore en México: Escultura, Dibujo, Grafica de 1921 a 1982, Museo de Arte Moderno, Mexico City, November 1982–January 1983, no.46.

1983

Henry Moore: Esculturas, Dibujos, Grabados – Obras de 1921 a 1982, Museum of Contemporary Art, Caracas, March 1983, no.113.

1986

The Art of Henry Moore: Sculptures, Drawings and Graphics 1921–1984, British Council touring exhibition: Metropolitan Art Museum, Tokyo, April–June 1986; Fukuoka Art Museum, Fukuoka, June–July 1986.

1988

Henry Moore, Royal Academy of Arts, London, September–December 1988, no.185.

1998

Henry Moore 1898–1986, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, March–August 1998, no.42.

2006–7

Henry Moore: The Challenge of Architecture, Rotterdam Kunsthal, Rotterdam, October 2006–January 2007.

References

1968

David Sylvester, Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Tate Gallery, London 1968, p.141 (plaster maquette reproduced pl.140).

1970

Robert Melville, Henry Moore: Sculpture and Drawings 1921–1969, London 1970, p.32 (original plaster for Three Piece Sculpture: Vertebrae 1968–9 reproduced nos.747–52).

1973

Henry J. Seldis, Henry Moore in America, New York 1973 (Three Piece Sculpture: Vertebrae 1968–9 reproduced p.241).

1973

John Russell, Henry Moore, London 1973 (Three Piece Sculpture: Vertebrae 1968–9 reproduced pl.154).

1977

Alan Bowness (ed.), Henry Moore. Volume 4: Complete Sculpture 1964–73, London 1977, no.579, p.51 (?another cast reproduced pls.88–91).

1977

David Finn, Henry Moore: Sculpture and Environment, New York 1977 (Three Piece Sculpture: Vertebrae 1968–9 reproduced pp.73–7).

1977

Henry Moore: Sculptures et dessins, exhibition catalogue, Musée de l’Orangerie des Tuileries, Paris 1977 (Three Piece Sculpture: Vertebrae 1968–9 reproduced no.110).

1978

Henry Moore 80th Birthday Exhibition, exhibition catalogue, Bradford Art Galleries and Museums, Bradford 1978, reproduced no.14.

1978

The Henry Moore Gift, exhibition catalogue, Tate Gallery 1978, reproduced front cover and p.62.

1979

Alan G. Wilkinson, The Moore Collection in the Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto.

1979

1979, p.202 (another cast reproduced pl.180).

1981

The Tate Gallery 1978–80: Illustrated Catalogue of Acquisitions, London 1981, pp.141–2, reproduced p.141.

1983

György Doczi, ‘Hidden Harmonies of Henry Moore’s Sculpture “Vertebrae”’, Leonardo, vol.16, no.1, Winter 1983, pp.36–7 (Three Piece Sculpture: Vertebrae 1968–9 reproduced p.36).

1987

Alan G. Wilkinson, Henry Moore Remembered: The Collection at the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto, Toronto 1987 (another cast reproduced p.231).

1988

Susan Compton (ed), Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Royal Academy of Arts, London 1988, pp.263–4, reproduced p.263.

1988

Richard Wentworth, ‘The Going Concern: Working for Moore’, Burlington Magazine, vol.130, no.1029, December 1988, pp.927–8, reproduced p.927.

1998

Henry Moore 1898–1986, exhibition catalogue, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna 1998, reproduced p.189.

2001

Dorothy Kosinski (ed.), Henry Moore: Sculpting the 20th Century, exhibition catalogue, Dallas Museum of Art, Dallas 2001 (Three Forms Vertebrae 1978–9 reproduced pp.296–307).

2006

David Mitchinson (ed.), Celebrating Moore: Works From the Collection of the Henry Moore Foundation, London 2006, pp.288–9 (Three Piece Sculpture: Vertebrae 1968–9 reproduced p.289).

2007

Jeremy Lewison, Henry Moore 1898–1986, Cologne 2007 (Three Forms Vertebrae 1978–9 reproduced p.79).

2013

Pauline Rose, Henry Moore in America: Art, Business and the Special Relationship, London 2013 (another cast reproduced p.112).

Technique and condition

This large bronze sculpture is made up of three separate parts mounted on a rectangular bronze base. Moore would have made the original model for this sculpture in plaster, which was built up in successive layers over a supportive armature probably made from wood. The hardened plaster would then have been smoothed with files and abrasives to remove the traces of tool marks from the surface. A mould would then have been taken from the completed plaster version that was used by the foundry to cast a hollow sculpture in bronze.

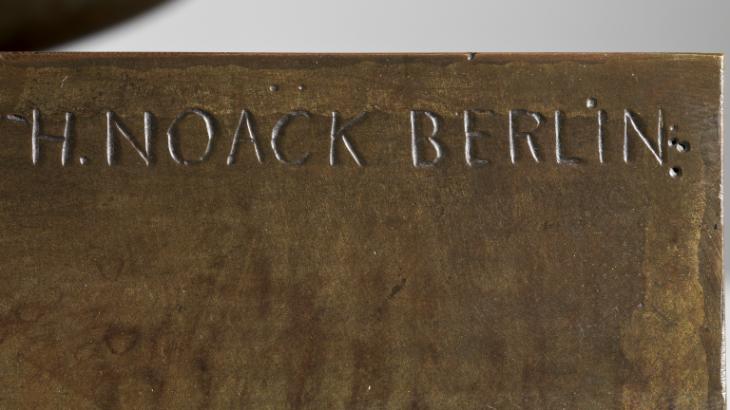

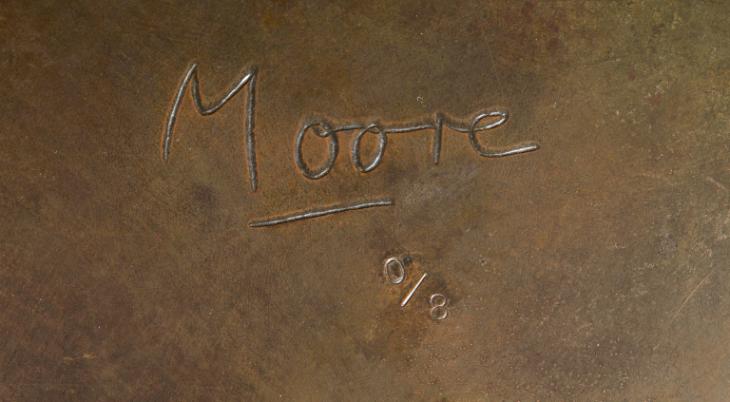

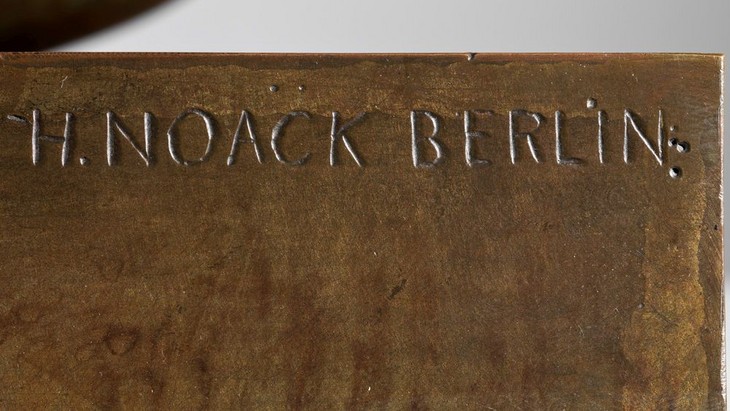

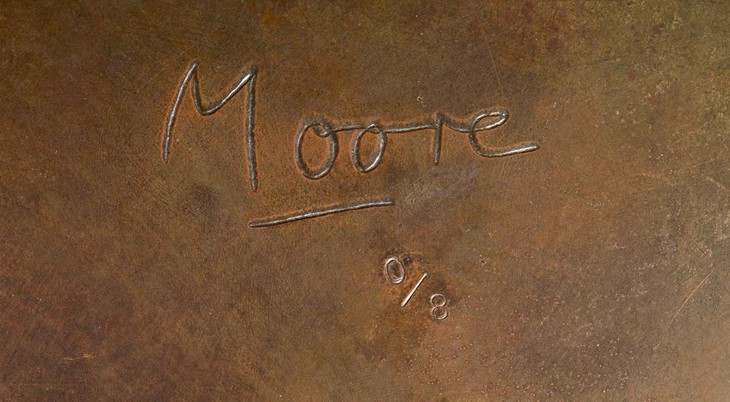

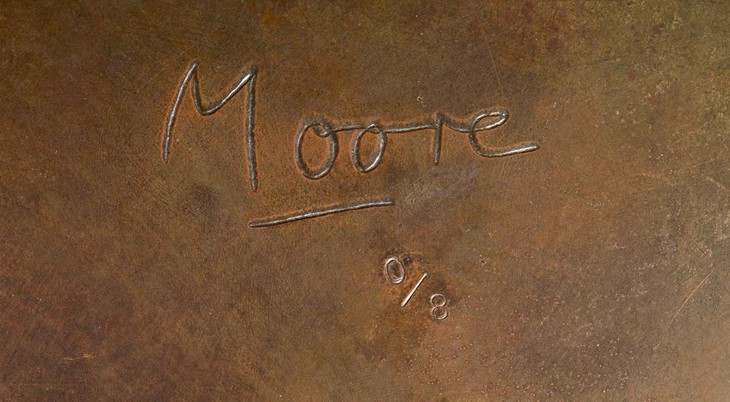

The sculpture was cast at the Noack Foundry in West Berlin in an edition of eight plus one artist’s copy. The foundry mark ‘H. NOACK BERLIN’ is inscribed on the base (fig.1). The maximum size of a cast piece of bronze is dependent on the size of the crucible that the foundry uses because the bronze must be cast in a single pour. In practice, this means that bronzes of this size are usually cast in a number of separate sections that are then welded together to form the whole. The base was also fabricated by welding bronze sheets together. These welds were then filed down and textured to match the surrounding surface, a process called ‘chasing’. The entire surface of this bronze was chased after casting using various grades of abrasives to produce the final smooth finish. There is, therefore, little evidence remaining to show what casting technique was used. The artist’s signature and edition number ‘Moore 0/8’ is inscribed on the top of the base in a corner (fig.2).

Detail of foundry mark on Working Model for Three Piece No.3: Vertebrae 1968, cast c.1968

Tate T02303

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.1

Detail of foundry mark on Working Model for Three Piece No.3: Vertebrae 1968, cast c.1968

Tate T02303

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Detail of artist's signature and edition number Working Model for Three Piece No.3: Vertebrae 1968, cast c.1968

Tate T02303

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.2

Detail of artist's signature and edition number Working Model for Three Piece No.3: Vertebrae 1968, cast c.1968

Tate T02303

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

After the bronze had been chased, it is likely that the foundry applied an artificial patina to the surfaces, which helped disguise welds and repairs. This involved applying chemical solutions to the surface that reacted with the metal to produce coloured compounds. In this case the patina is a mid-brown colour, but this has been rubbed back in places to reveal an underlying golden tone, especially on the high points and sharp edges. This is enhanced by a warmer transparent brown patina that was applied in some areas, probably using a ferric nitrate solution. There are signs that a lacquer was originally used to protect this patina and preserve the lighter colours, but this has broken down on the high points, which has allowed a natural patina to establish itself over time (fig.3).

The three parts of the sculpture are fixed to the base by eight threaded bolts inserted from underneath: three bolts in two of the parts and one in the other. There are two threaded holes on either side of the base, which were made to accommodate specialist eye bolts used as fixing points for slings or chains that allow the sculpture to be safely lifted into position. Lifting attachments are often found on Moore’s large-scale sculptures and reveal that Moore thought carefully about how these works might be installed.

Since entering the Tate collection in 1978 this sculpture has been on loan to a number of institutions and was displayed outside for long periods, during which time it became marked with graffiti and scratches. In 2007 it was decided that major restoration treatment should be undertaken at the Henry Moore Foundation to repair the damage. There was some deeply inscribed graffiti on the base that could not be successfully retouched using conventional conservation techniques, so it was necessary to re-finish the bronze surface in these areas. This process involved the removal of the original patina before repatinating the affected areas to match the surrounding colour. To do this the restorers used chemical solutions that are often used by foundries, namely potassium polysulphide (often known as ‘liver of sulphur’) and ferric nitrate, before applying coloured waxes to complete the restoration.

Lyndsey Morgan

March 2013

How to cite

Lyndsey Morgan, 'Technique and Condition', March 2013, in Alice Correia, ‘Working Model for Three Piece No.3: Vertebrae 1968, cast c.1968 by Henry Moore OM, CH’, catalogue entry, March 2014, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015, https://wwwEntry

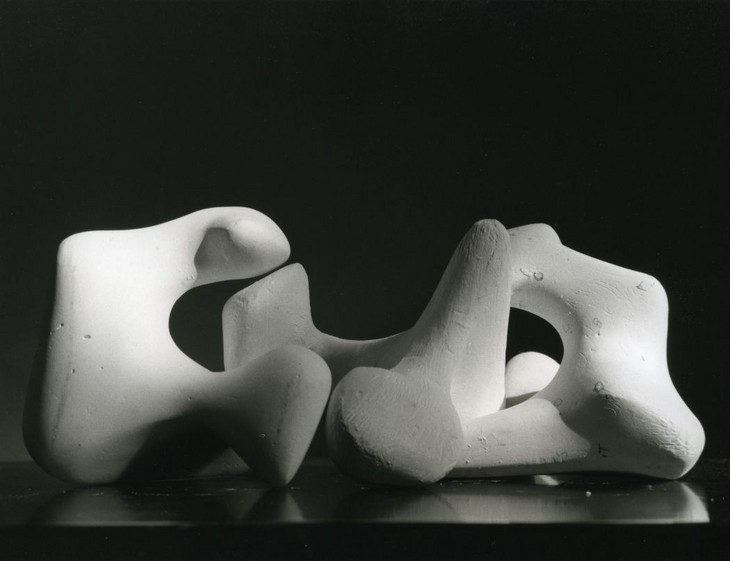

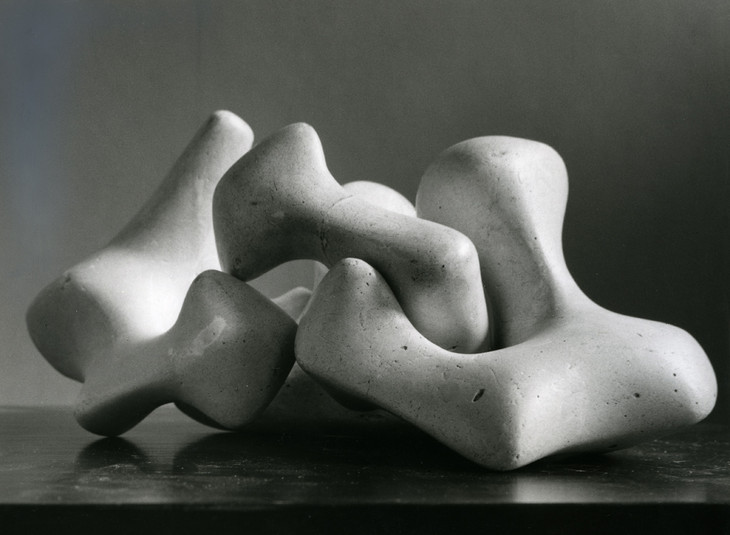

Working Model for Three Piece No.3: Vertebrae is a large-scale model for a monumental bronze sculpture measuring over seven metres long. Tate’s work represents the intermediary stage in the gradual enlargement of the sculpture, which comprises three individual parts mounted on a bronze base (fig.1). These three bone-like components are arranged horizontally along the length of the rectangular base and feature projecting forms that interlock with those of the adjacent component. While each part is uniquely shaped and orientated, Moore ensured that they were sufficiently similar to create uniformity across the sculpture. Each piece has three main spurs: a thin, tubular form that terminates in a rounded tip, a short bulbous form, and another tubular form with a wide circumference that bends at a right angle and culminates in an engorged pyramidal point. Cumulatively, the sculpture is made up of contrasting spiky and rounded protrusions and curved and sharp edges. The thinner tapered tubular limbs of the outer two pieces book-end the sculpture, while the right-angled section of the middle piece creates a cantilevered, horizontal bridge-like form (fig.2). The work is designed to be viewed in the round so that no two views are the same and there is no definitive front or back. Considering the full-size version of this sculpture, the art historian Norbert Lynton noted in 2006 that although ‘the three elements are similar but not identical ... the experience offered is still one of variety within repetition’.1 The sculpture has a smooth, highly polished and reflective surface that heightens its tactile qualities.

Henry Moore

Working Model for Three Piece No.3: Vertebrae 1968, cast c.1968

Tate T02303

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.1

Henry Moore

Working Model for Three Piece No.3: Vertebrae 1968, cast c.1968

Tate T02303

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore

Working Model for Three Piece No.3: Vertebrae 1968, cast c.1968

Tate T02303

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.2

Henry Moore

Working Model for Three Piece No.3: Vertebrae 1968, cast c.1968

Tate T02303

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

From plaster to bronze

This sculpture was developed from a small maquette made in plaster in 1968.2 By this time Moore had established a practice of testing out his designs for sculptures by making small three-dimensional sketch-models as opposed to drawing his ideas on a page. In 1978 he explained:

I have gradually changed from using preliminary drawings for my sculptures to working from the beginning in three-dimensions. That is, I first make a maquette for any idea I have for a sculpture. The maquette is only three or four inches in size, and I can hold it in my hand, turning it over to look at it from above, underneath, and in fact from any angle.3

It is probable that Moore made the small model in his maquette studio in the grounds of his home, Hoglands, at Perry Green in Hertfordshire. This studio housed his ever growing collection of found objects, including bones, shells and flint stones, the shapes of which often served as starting points for Moore’s formal experiments in three dimensions. In 1963 Moore explained to critic David Sylvester how he worked with these objects:

I look at them, handle them, see them from all round, and I may press then into clay and pour plaster into that clay and get a start as a bit of plaster, which is a reproduction of the object. And then add to it, change it. In that sort of way something turns out in the end that you could never have thought of the day before.4

Flint stones in Henry Moore's studio

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.3

Flint stones in Henry Moore's studio

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

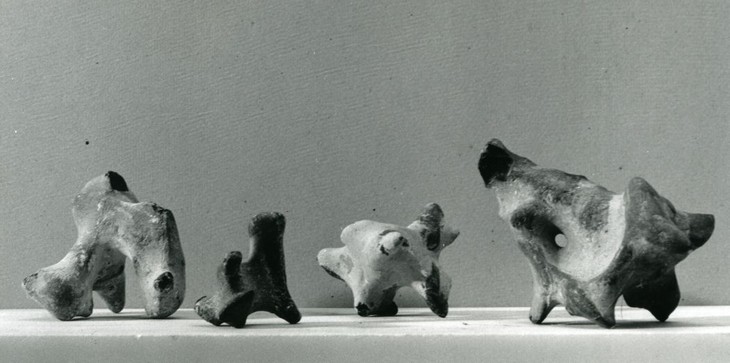

Maquette for Three Piece No.3: Vertebrae 1968

Plaster

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.4

Maquette for Three Piece No.3: Vertebrae 1968

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Maquette for Three Piece No.3: Vertebrae 1968

Plaster

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.5

Maquette for Three Piece No.3: Vertebrae 1968

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Archival photographs of the maquette illustrate how Moore experimented with the arrangement of the component parts (figs.4 and 5). A comparison of these photographs reveals that Moore considered the rhythms created by the interaction of the forms, and assessed whether they should be dispersed across the base or clustered together. After settling on the final arrangement Moore would have used the maquette as a template for Tate’s larger working model. By charting and measuring specific points on the surface of the maquette it was possible to make an exact enlargement of the sculpture. Much, if not all of this work would have been undertaken by Moore’s studio assistants, who at the time included the sculptor Richard Wentworth. In 1988 Wentworth recalled the methods used to scale up Moore’s sculptures:

Distinct points on the surface of the maquette are identified as ‘landmarks’ and each is known by a letter of the alphabet. The maquette is placed on squared paper so that a list of co-ordinates can be drawn up for each ‘landmark’ – how much it is above the surface it sits on, how much from the ‘front’ or ‘back’ or how much from the ‘left’ or ‘right’. The success of this mechanical method is dependent on how thoroughly these measurements are taken. By measuring off a grid, five, eight or twelve times bigger, all these points can be plotted in space.7

Wentworth recalled that he worked on ‘one of the parts for Three Piece No.3 Vertebrae’ and his text, published in the Burlington Magazine, was accompanied by an illustration of Tate’s sculpture, suggesting that he constructed one of the plaster components for the working model rather than the final monumental bronze.

In order to make the working model plaster from which Tate’s bronze was eventually cast, Wentworth and Moore’s other assistants, including Yeheskiel Yardini, would have initially constructed an armature to the required size and shape for each section of the sculpture. The armature was made up of numerous lengths of wood, which not only provided a supportive frame, but the tips of which corresponded to a point on the surface of the sculpture identified on the maquette. These rods were then draped in scrim, a bandage like fabric, onto which wet plaster could be applied to create a hard shell. Layers of plaster were then built up to create the basic shape while the interior of the plaster remained hollow.

After the plaster components had been modelled to the required shape and size, Moore could concentrate on their surface texture. Using an array of tools, including chisels, files and sandpaper, he and his assistants could create different types of textures depending on the wetness of the plaster. Moore found plaster to be a very useful material because it could be ‘both built up, as in modelling, or cut down, in the way you carve stone or wood’.8 The surface texture of the plaster was captured in the bronze casting process and in 1977 the curator Alan Bowness noted that ‘most of the post-war bronzes had rough, variegated textures, but from 1963 or so Moore began to introduce smooth and polished bronze surfaces’ as seen in this work.9

Once Moore was satisfied with the surface finish of the sculpture and was sure that he wanted to proceed with the casting process, he sent the three plaster parts to the Noack Foundry in West Berlin to be cast in bronze. In 1967 Moore stated, ‘I use the Noack foundry for casting most of my work because in my opinion, Noack is the best bronze founder I know ... Also, the Noack foundry is reliable in all ways – in keeping to dates of delivery – and in sustaining the quality of their work’.10 It is unclear which technique was used to cast this bronze sculpture for it is known that Noack used the lost wax and sand casting methods. Welding seams were also disguised after casting when the sculpture underwent considerable treatment to create the smooth all-over surface finish.

Working Model for Three Piece No.3: Vertebrae 1968 in Moore's studio

Tate T02303

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.6

Working Model for Three Piece No.3: Vertebrae 1968 in Moore's studio

Tate T02303

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Tate’s example of Working Model for Three Piece No.3: Vertebrae underwent major restoration treatment in 2007 at the Henry Moore Foundation. Scratches and graffiti on the surface of the sculpture and the base were removed, which subsequently required localised repatination. The sculpture has a variegated patina with an underlying golden-brown colour highlighted with deep red and a chestnut-brown, which provide a range of warm tones (fig.7). The sharper edges of the sculpture have being polished to reveal the underlying golden colour of the bronze. Working Model for Three Piece No.3: Vertebrae was cast in an edition of eight plus one artist’s copy. Tate’s example is stamped with the artist’s signature and the number ‘0/8’ on the base; the ‘0’ indicates that this work was the artist’s copy (fig.8). Other examples are held in the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington D.C.; the Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto; the Memorial Art Gallery, Rochester; and the Nasher Sculpture Center, Dallas. The remaining casts are believed to be held in private collections.

Working Model for Three Piece No.3: Vertebrae 1968, cast c.1968 (side view showing patina)

Tate T02303

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.7

Working Model for Three Piece No.3: Vertebrae 1968, cast c.1968 (side view showing patina)

Tate T02303

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Detail of artist's signature and edition number Working Model for Three Piece No.3: Vertebrae 1968, cast c.1968

Tate T02303

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.8

Detail of artist's signature and edition number Working Model for Three Piece No.3: Vertebrae 1968, cast c.1968

Tate T02303

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

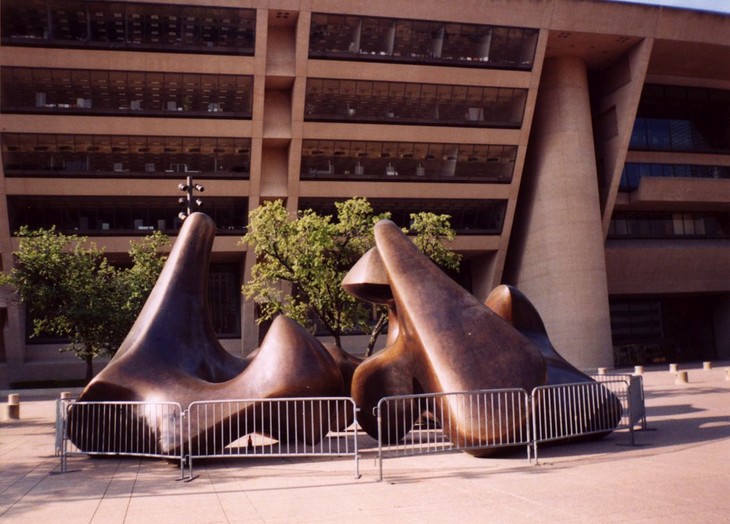

The whereabouts of the original plaster from which the bronze edition was cast are unknown, but photographs reveal that it was used as the template for the large-scale version of the sculpture, known as Three Piece Sculpture: Vertebrae 1968–9 (fig.9).12 This work was enlarged using the same technique that Wentworth had used to enlarge the working model from the maquette. In 1976 Moore was commissioned by the City of Dallas to create a sculpture that would be sited in the plaza in front of the newly built City Hall, designed by architect I.M. Pei. Moore disliked commissions that demanded that he conform to a set of requirements, preferring instead to remodel or develop a work already in progress. For the Dallas commission Moore decided that an enlarged version of Three Piece Sculpture: Vertebrae would be suitable, but Pei ‘proposed that the component parts should be rearranged’ in a triangular cluster so that visitors to the plaza would be able to walk though and interact with the sculpture.13 In December 1978 Moore visited the United States for the installation of Three Forms Vertebrae 1978–9, known locally as Dallas Piece (fig.10).14 Of the work Moore stated:

I was very relieved to find it right in its size and in its colour. You have the strong big powerful forms of the building. I didn’t want the sculpture so underdone that it’s weak. It may seem to some people abstract but it’s not. It’s all organic form. You might say it’s like a whale coming out of water. I have no objection if somebody wants to think of it in that way. Sea animals have to be smooth to go through the water. Or you might think it’s something entirely different.15

Plaster version of full-size Three Piece Sculpture: Vertebrae alongside the plaster version of Working Model for Three Piece No.3: Vertebrae in the plastic studio at Hoglands c.1968

Tate T02303

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.9

Plaster version of full-size Three Piece Sculpture: Vertebrae alongside the plaster version of Working Model for Three Piece No.3: Vertebrae in the plastic studio at Hoglands c.1968

Tate T02303

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

View of Henry Moore's Three Forms Vertebrae 1978 outside Dallas City Hall 2003

Photo: Pauline Rose

Fig.10

View of Henry Moore's Three Forms Vertebrae 1978 outside Dallas City Hall 2003

Photo: Pauline Rose

Origins and interpretation

Henry Moore

Three Piece Reclining Figure No.1 1961–2

Tate T02289

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.11

Henry Moore

Three Piece Reclining Figure No.1 1961–2

Tate T02289

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

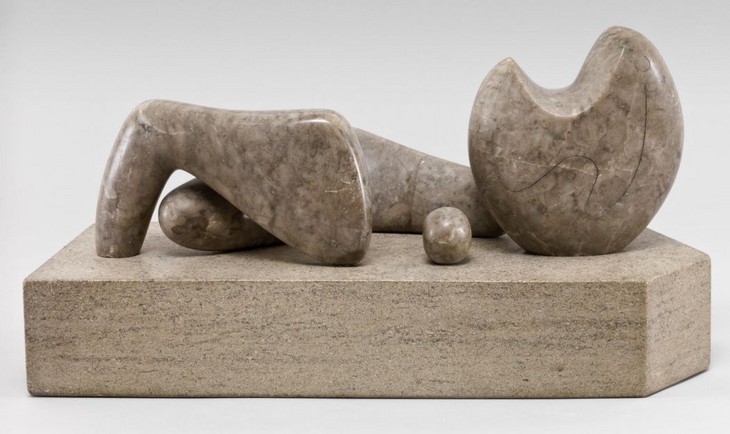

The two-piece sculptures pose a problem like the kind of relationship between two people. And it’s very different once you divide a thing into three: then you have two ends and a middle. In the two-piece you have just the head end and the body end or the head end and the leg end, but once you get the three-piece you have the middle and the two ends, and this became something that I wanted to do, having done the two-piece. I tried several little ideas before this one [Three Piece Reclining Figure No.1] and what led me to this solution was finding a little piece of bone that was the middle of a vertebra, and I realised then that perhaps the connection through, of one piece to another, could have gone on and made a four- or five-piece, like a snake with its vertebrae right through from one end to the other. But three is enough to make the difference from two. That is what one tried to make: it is a connecting-piece carrying through from one end to the other like you might have with a snake.16

Henry Moore

Four-Piece Composition: Reclining Figure 1934

Cumberland alabaster on a Purbeck marble base

175 x 457 x 203 mm

Tate T02054

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.12

Henry Moore

Four-Piece Composition: Reclining Figure 1934

Tate T02054

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

With these precedents in mind, the central component of Working Model for Three Piece No.3: Vertebrae may be regarded as the vertabra or umbilicus, connecting and relating the two end pieces together to create a unified entity. As the curator Alan Bowness has suggested, ‘the reclining figure component is less important than the way the three forms lock together like the bones of a spinal column. The fascination with locking forms is one general characteristic of ... [Moore’s] late style’.19 Reflecting on his series of vertebrae sculptures, Moore stated,

each of the forms, although different, has the same basic shape. Just as in a backbone which may be made up of twenty segments where each one is roughly like the others but not exactly the same ... This is why I call these sculptures Vertebrae. The two or three forms are basically alike but are arranged to go with each other in different positions. The sculptor’s life is one of thinking, reacting, or making, expressing himself through form, through shape – for me the three-dimensional world is unending.20

In a conversation with Tate researcher Richard Calvocoressi on 12 December 1980 Moore explained that in thinking about the vertebral column, ‘what interested him was the idea of a series or progression of similar forms’.21 These interests can also be seen in Moore’s large sculpture Locking Piece 1963–4 (Tate T02293).

In 1983 the architect György Doczi developed this idea of singular components coming together to form a whole. He suggested that Moore’s monumental Three Piece Sculpture: Vertebrae adhered to the harmonious proportions of the golden ratio, where the distance between the sculpture’s two upper-most tips is twice as long as the distance from each tip to its respective outer-most edge. ‘Golden’ proportions occur naturally in plants, animals and organic matter, and Doczi asserted that ‘a great artist creates harmonies in the same way as does nature herself, because he or she is truly at one with nature’.22 He concluded that ‘Moore’s sculpture is a model of ... harmonious sharing’, where each component is predisposed to work in unison with the other in order to form a whole.23 In 1978 Moore simply said of Three Piece Sculpture: Vertebrae, ‘the inspiration is life. I look upon then [sic] as life. It couldn’t be what it is unless I had been excited by the human figure’.24

The Henry Moore Gift

Working Model for Three Piece No.3: Vertebrae was presented by Henry Moore to the Tate Gallery in 1978 as part of the Henry Moore Gift, which comprised thirty-six sculptures in bronze, marble and plaster. Moore first indicated his plan to give the gallery a large selection of his work in the early 1960s, and in June 1969 a deed of agreement was signed, which outlined the terms of the Gift and the works included in it. It was agreed that the works would remain in Moore’s possession for his lifetime, should he so choose. However, in 1977 Tate’s director Norman Reid petitioned Moore to present his Gift so that it could be displayed in its entirety alongside the Tate’s existing collection of his work in an exhibition celebrating the artist’s eightieth birthday scheduled for the following year. Moore duly agreed and the Gift was delivered to the Tate in June 1978. A press release was prepared announcing that ‘The group [of sculptures] is the most substantial gift of works ever given to the Tate by an artist during his lifetime’.25 The exhibition was attended by over 20,500 people and nearly 11,000 copies of the catalogue were sold.26 At its close in late August the Director of Tate, Norman Reid, reflected in a letter to Moore’s daughter Mary Danowski that although he was sad to see the exhibition come to an end ‘we have the consolation of the splendid group of sculptures which Henry has presented to the nation’.27

Following the exhibition the Tate Trustees decided to lend, on a long term basis, those sculptures for which there were no immediate exhibition plans to select regional galleries and museums. Rather than keep large works in storage it was agreed, with the artist’s approval, that it would be advantageous – for Tate and for the recipient galleries – for the works to be dispersed across the country. In March 1979 it was agreed that Working Model for Three Piece No.3: Vertebrae would be exhibited at the University of Reading, where it was installed outside on 19 July. Most loans under this scheme were made for five-year periods. However, by the end of 1981 Working Model for Three Piece No.3: Vertebrae, along with a number of other works on loan, was recalled for Moore’s British Council exhibitions in Spain, Portugal, Mexico, Venezuela and Japan.

Alice Correia

March 2014

Notes

Norbert Lynton, ‘Three Piece Sculpture: Vertebrae 1968’, in David Mitchinson (ed.), Celebrating Moore: Works From the Collection of the Henry Moore Foundation, London 2006, p.289.

See Alan Bowness (ed.), Henry Moore. Volume 4: Complete Sculpture 1964–73, London 1977, p.51, no.578. The maquette was later cast in a bronze edition of seven plus one artist’s copy.

Henry Moore in ‘Henry Moore Talking to David Sylvester’, 7 June 1963, transcript of Third Programme, BBC Radio, broadcast 14 July 1963, p.18, Tate Archive TGA 200816. (An edited version of this interview was published in the Listener, 29 August 1963, pp.305–7.)

Alan G. Wilkinson, Henry Moore Remembered: The Collection at the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto, Toronto 1987, p.231.

Henry Moore cited in ‘Interview: Conversation between Sir [sic] Henry Moore, Wolfgang Fischer and Erich Steingräber in Much Hadham on April 3, 1978’, in Erich Steingräber, Henry Moore Maquetten, Munich 1978, p.55.

Richard Wentworth, ‘The Going Concern: Working for Moore’, Burlington Magazine, vol.130, no.1029, December 1988, pp.927–8.

Three Piece Sculpture: Vertebrae 1968–9 was cast in an edition of three plus one artist’s copy. Examples are held in the collections of the Seattle Art Museum; the Israel Museum, Jerusalem; and Himmelreichallee, Münster. The artist’s copy remains in the collection of the Henry Moore Foundation.

Henry Moore cited in Bill Marvell, ‘The Dallas Piece: It Just Fits the City’, Dallas Times Herald, 6 December 1978, Henry Moore Foundation Archive.

[Richard Morphet], ‘T.2054 Henry Moore: Four-Piece Composition 1934’, The Tate Gallery 1976–8: Illustrated Catalogue of Acquisitions, London 1979, p.121.

Henry Moore cited in David Mitchinson (ed.), Henry Moore Sculpture with Comments by the Artist, Barcelona 1988, p.204.

Richard Calvocoressi, ‘Henry Moore, Working Model for Three Piece No.3: Vertebrae 1968’, The Tate Gallery 1978–80: Illustrated Catalogue of Acquisitions, London 1981, pp.141–2.

György Doczi, ‘Hidden Harmonies of Henry Moore’s Sculpture “Vertebrae”’, Leonardo, vol.16, no.1, winter 1983, p.37.

Related essays

- Henry Moore’s American Patrons and Public Commissions Pauline Rose

- Scale at Any Size: Henry Moore and Scaling Up Rachel Wells

- Fashioning a Post-War Reputation: Henry Moore as a Civic Sculptor c.1943–58 Andrew Stephenson

- Henry Moore: The Plasters Anita Feldman

- Life Forms: Henry Moore, Morphology and Biologism in the Interwar Years Edward Juler

- Henry Moore's Approach to Bronze Lyndsey Morgan and Rozemarijn van der Molen

Related catalogue entries

Related material

-

Photograph

Related reviews and articles

- Richard Wentworth, ‘The Going Concern: Working for Moore’ Burlington Magazine, vol.130, no.1029, December 1988, pp.972–78.

How to cite

Alice Correia, ‘Working Model for Three Piece No.3: Vertebrae 1968, cast c.1968 by Henry Moore OM, CH’, catalogue entry, March 2014, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015, https://www