Henry Moore OM, CH Two Piece Reclining Figure No.5 1963-4, cast date unknown

Image 1 of 15

-

Henry Moore OM, CH, Two Piece Reclining Figure No.5 1963-4, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Two Piece Reclining Figure No.5 1963-4, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Two Piece Reclining Figure No.5 1963-4, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Two Piece Reclining Figure No.5 1963-4, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Two Piece Reclining Figure No.5 1963-4, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Two Piece Reclining Figure No.5 1963-4, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Two Piece Reclining Figure No.5 1963-4, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Two Piece Reclining Figure No.5 1963-4, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Two Piece Reclining Figure No.5 1963-4, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Two Piece Reclining Figure No.5 1963-4, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Two Piece Reclining Figure No.5 1963-4, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Two Piece Reclining Figure No.5 1963-4, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Two Piece Reclining Figure No.5 1963-4, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Two Piece Reclining Figure No.5 1963-4, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Two Piece Reclining Figure No.5 1963-4, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Two Piece Reclining Figure No.5 1963-4, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Two Piece Reclining Figure No.5 1963-4, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Two Piece Reclining Figure No.5 1963-4, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Two Piece Reclining Figure No.5 1963-4, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Two Piece Reclining Figure No.5 1963-4, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Two Piece Reclining Figure No.5 1963-4, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Two Piece Reclining Figure No.5 1963-4, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Two Piece Reclining Figure No.5 1963-4, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Two Piece Reclining Figure No.5 1963-4, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Two Piece Reclining Figure No.5 1963-4, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Two Piece Reclining Figure No.5 1963-4, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Two Piece Reclining Figure No.5 1963-4, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Two Piece Reclining Figure No.5 1963-4, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Two Piece Reclining Figure No.5 1963-4, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Two Piece Reclining Figure No.5 1963-4, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH,

Two Piece Reclining Figure No.5

1963-4, cast date unknown

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Standfirst:

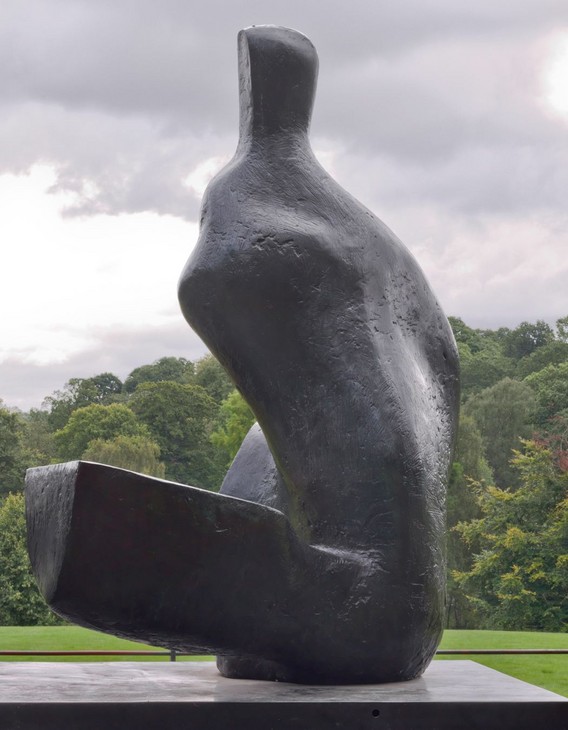

Divided into two pieces that resemble boulders more than body parts, this reclining figure exemplifies Moore’s interest in the coalescence of human and geological imagery. The work also demonstrates his concern with the figure in space in that relationships between forms appear to change when the sculpture is viewed in the round.

Divided into two pieces that resemble boulders more than body parts, this reclining figure exemplifies Moore’s interest in the coalescence of human and geological imagery. The work also demonstrates his concern with the figure in space in that relationships between forms appear to change when the sculpture is viewed in the round.

Henry Moore OM, CH 1898–1986

Two Piece Reclining Figure No.5

1963–4, cast date unknown

Bronze

2375 x 3684 x 1988 mm

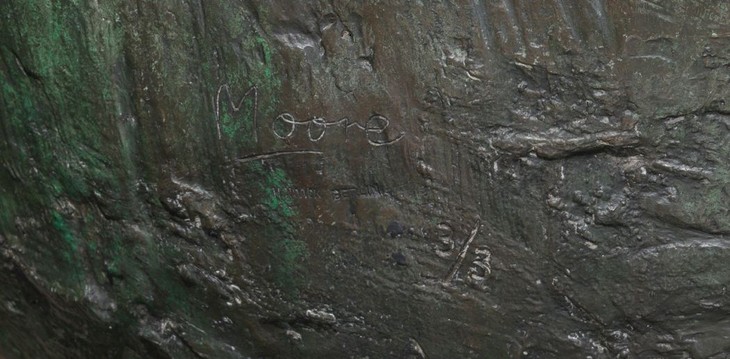

Inscribed ‘Moore 3/3’ and stamped with foundry mark ‘H. NOACK BERLIN’ on lower rear of torso piece

Artist’s copy aside from edition of 3

Presented by the artist 1978

T02294

Two Piece Reclining Figure No.5

1963–4, cast date unknown

Bronze

2375 x 3684 x 1988 mm

Inscribed ‘Moore 3/3’ and stamped with foundry mark ‘H. NOACK BERLIN’ on lower rear of torso piece

Artist’s copy aside from edition of 3

Presented by the artist 1978

T02294

Ownership history

Presented by the artist to Tate in 1978 as part of the Henry Moore Gift.

Exhibition history

1966

Sculpture in the Open Air, Battersea Park, London, May–September 1966, no.28.

1978

The Henry Moore Gift, Tate Gallery, London, June–August 1978, no number.

References

1965

Herbert Read, Henry Moore: A Study of His Life and Work, London 1965, p.235 (?another cast reproduced pl.222).

1966

Sculpture in the Open Air, exhibition catalogue, Battersea Park, London 1966, reproduced.

1966

Philip James (ed.), Henry Moore on Sculpture, London 1966, pl.15..

1977

Alan Bowness (ed.), Henry Moore. Volume 4: Complete Sculpture 1964–73, London 1977, no.517, reproduced pls.6–7.

1978

The Henry Moore Gift, exhibition catalogue, Tate Gallery, London 1978, reproduced p.54.

1981

The Tate Gallery 1978–80: Illustrated Catalogue of Acquisitions, London 1981, pp.134–5, reproduced p.134.

1984

Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Herning Kunstmuseum, Herning 1984, pp.31–6.

2006

Patrick Eyres and Fiona Russell, ‘Modernism, Postmodernism, Landscape and Regeneration’, in Patrick Eyres and Fiona Russell (eds.), Sculpture in the Garden, Aldershot 2006, p.116 (?another cast reproduced pp.113–19, pl.0.11).

Technique and condition

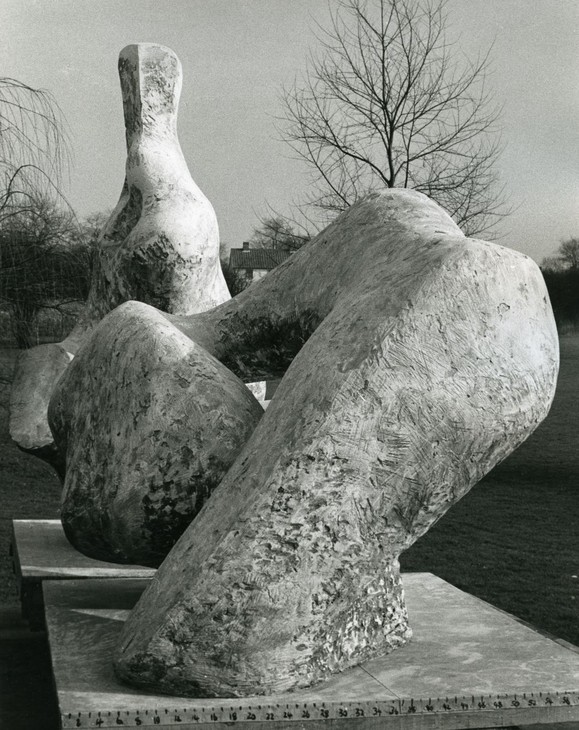

This is a bronze sculpture of a large reclining figure in two parts, currently displayed in the grounds of Kenwood House, London. Moore would have made the original model for this sculpture by applying successive layers of plaster to a supportive armature, probably constructed from lengths of wood. Marks on the surface show how Moore modified the texture of the plaster by exploiting its properties at various stages of the setting process. He combined the techniques of modeling and carving, adding wet plaster with a spatula and using sharp tools to make deep striations into the plaster while it was still slightly wet, and carving or filing the surface when it was almost dry (fig.1). Once this plaster was complete a mould was taken from it so that it could be cast in bronze at the foundry. This sculpture was cast at the Noack Foundry in West Berlin in an edition of three plus one artist’s copy.

The maximum size of a cast piece of bronze is dependent on the crucible size that the foundry uses because the bronze must be cast in a single pour. In practice this means that bronzes of this size are usually cast in a number of separate sections that are then welded together to form the whole. Horizontal weld lines just below the shoulders of the torso provide evidence that this process was used to cast Two Piece Reclining Figure No.5 (fig.2). These welds would have been filed and textured to match the surrounding bronze surface by means of a process known as ‘chasing’.

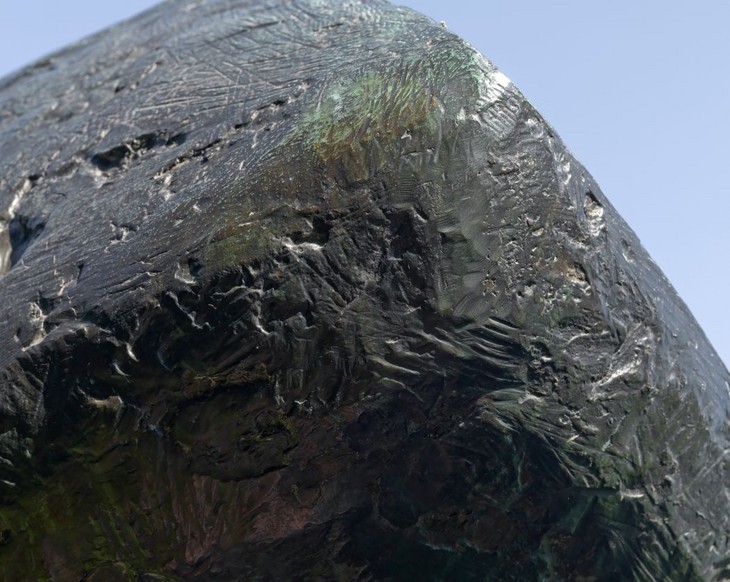

After the sculpture had been cleaned the surface was coloured using an artificial patina. This process involved the application of chemical solutions to the surface that reacted with the bronze to produce coloured compounds. The original patina has gradually altered as a result of further chemical reactions induced by the outdoor environment to which the sculpture has been exposed for many years. The original, uniform brown patina is still clearly visible but the surface has become variegated. Areas of green patina now overlay the brown, particularly on high points.

Detail of green water marks on Two Piece Reclining Figure No.5 1963–4, cast date unknown

Tate T02294

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.3

Detail of green water marks on Two Piece Reclining Figure No.5 1963–4, cast date unknown

Tate T02294

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Detail of signature, foundry stamp and edition number on Two Piece Reclining Figure No.5 1963–4, cast date unknown

Tate T02294

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.4

Detail of signature, foundry stamp and edition number on Two Piece Reclining Figure No.5 1963–4, cast date unknown

Tate T02294

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

The two parts of the sculpture are fixed to a rectangular bronze base at three points by bolts that attach from underneath. There are three threaded holes on either side of the base made to accept specialist eye bolts which are used as fixing points for slings or chains and allow the sculpture to be safely lifted into position. Lifting attachments are often found on Moore’s monumental sculptures and show how the method of installation was considered from the outset. The base sits upon a cuboid plinth clad with vertically mounted slabs of green slate.

When the sculpture was on display on the Tate Gallery lawn in 1981 it was installed on a new protective plinth. It was relocated to Kenwood House, London, in 1983, but in 1992 it was observed that welded joints on the base had opened up as a result of children climbing on the sculpture. As a result Two Piece Reclining Figure No.5 was removed from the Kenwood House site and sent to be repaired at the Morris Singer Foundry. At the same time the structure of the base was reinforced and the fixings were improved. The sculpture was returned to Kenwood in 1993 on the site where Moore originally located the sculpture. A low hedge was installed as a deterrent to those who wished to climb on the sculpture but damage continued to be inflicted upon it. It was eventually agreed that more robust protection was necessary in the form of a protective fence, which was installed in 2001 and remains around the sculpture.

Tate’s outdoor sculptures are maintained on a yearly basis. This involves checking them for any signs of deterioration, washing them to remove dirt and bird lime and, usually, applying a clear wax to protect the surface from weathering.

Lyndsey Morgan

March 2013

How to cite

Lyndsey Morgan, 'Technique and Condition', March 2013, in Alice Correia, ‘Two Piece Reclining Figure No.5 1963–4, cast date unknown by Henry Moore OM, CH’, catalogue entry, August 2013, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015, https://wwwEntry

Made in 1963–4, Two Piece Reclining Figure No.5 is the fifth work in a series of two-piece sculptures that Moore began in 1959 and developed throughout the 1960s. It comprises two separate bronze forms attached to a bronze base that together represent a reclining human figure, although the boulder-like shapes of the forms, coupled with their separation, render this identification problematic (fig.1).

The vertically orientated form contains more elements identifiable with the human body, most notably an upright protrusion that occupies the position of a head, which features two flat sides separated by a vertical ridge akin to a nose (fig.2). The central mass of this section of the body is thin and long, although bulbous forms emerge from the area just below the head and may denote shoulders or breasts, although on one side these forms contain oval-shaped depressions. Two truncated appendages made up of flat and rounded faces project outwards from the central body at different angles into the gap between the two separate pieces of the sculpture and may be regarded as limbs (fig.3).

Detail of upper body of Two Piece Reclining Figure No.5 1963–4, cast date unknown (side view)

Tate T02294

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.2

Detail of upper body of Two Piece Reclining Figure No.5 1963–4, cast date unknown (side view)

Tate T02294

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Detail of upper body of Two Piece Reclining Figure No.5 1963–4, cast date unknown (rear view)

Tate T02294

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.3

Detail of upper body of Two Piece Reclining Figure No.5 1963–4, cast date unknown (rear view)

Tate T02294

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

From certain angles the other piece of the sculpture appears to be comprised of two interlocking forms, but the flat surface facing the gap between the two parts of the sculpture reveals that this single unit has been sculpted so that two forms appear to project from this face at different heights and angles (fig.4). One of these extends diagonally upwards from the base in the shape of a cylinder before swelling into a bulbous mass, while the other form arches over and around it until it reaches the base. Viewed from one side of the sculpture these two forms might be deemed to represent one leg crossing another (fig.5). Although Moore’s large-scale reclining figures are usually identified as female, the gender of the figure is not stated in the title nor easily ascertained by looking at the sculpture itself.

Detail of leg section of Two Piece Reclining Figure No.5 1963–4, cast date unknown

Tate T02294

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.4

Detail of leg section of Two Piece Reclining Figure No.5 1963–4, cast date unknown

Tate T02294

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Detail of leg section of Two Piece Reclining Figure No.5 1963–4, cast date unknown

Tate T02294

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.5

Detail of leg section of Two Piece Reclining Figure No.5 1963–4, cast date unknown

Tate T02294

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

From plaster to bronze

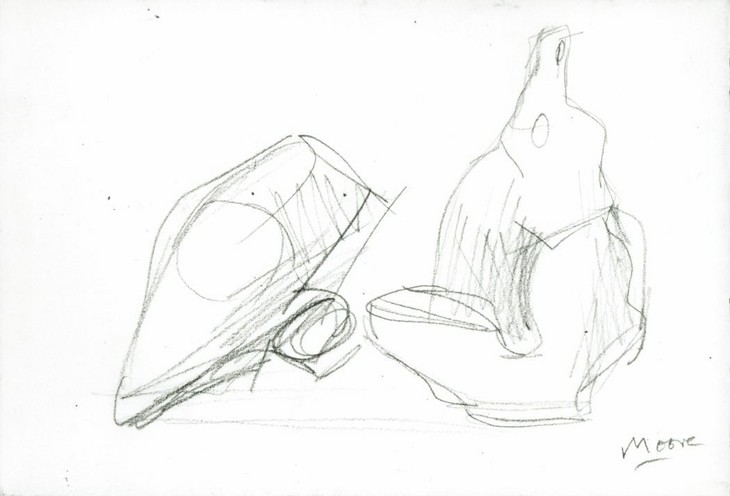

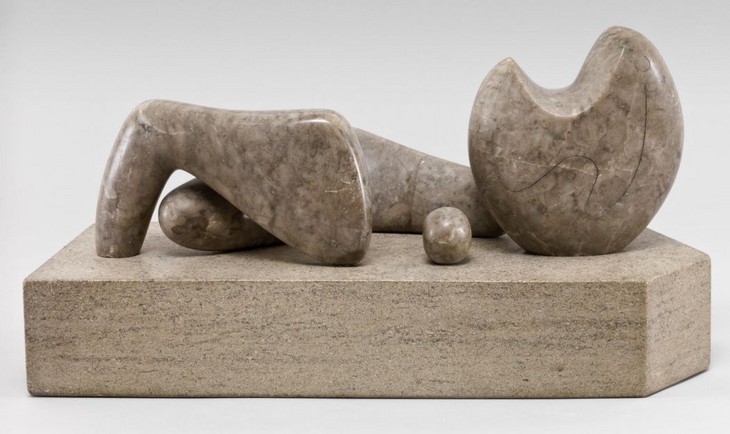

Moore began developing ideas for two-piece reclining figures in 1959 with a series of small plaster maquettes. By this time Moore had moved away from making preliminary drawings for his sculptures but some designs on paper did support and supplement his three-dimensional models even if they did not determine their eventual form. For example, the torso section of Two Piece Reclining Figure 1959 (fig.6) seems to anticipate the torso section of Two Piece Reclining Figure No.5, especially the oval area in the neck and the extended leg.

Flint pebbles arranged in Henry Moore's studio

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.7

Flint pebbles arranged in Henry Moore's studio

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

I look at them, handle them, see them from all round, and I may press then into clay and pour plaster into that clay and get a start as a bit of plaster, which is a reproduction of the object. And then add to it, change it. In that sort of way something turns out in the end that you could never have thought of the day before. This to me now is the beauty of each day if one’s working – that by the end of it you might have had something happen that you couldn’t possibly have foreseen.3

Moore made numerous maquettes for two-piece sculptures between 1959 and 1964, sometimes making only very slight alterations between each. Moore explained:

Sometimes I make ten or twenty maquettes for every one that I use in a large scale – the others may get rejected. If a maquette keeps its interest enough for me to want to realise it as a full-size final work, then I might make a working model in an intermediate size, in which changes will be made before going to the real, full-sized sculpture. Changes get made at all these stages.4

Henry Moore

Two Piece Reclining Figure: Maquette No.3 1961

Painted plaster

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Alice Correia

Fig.8

Henry Moore

Two Piece Reclining Figure: Maquette No.3 1961

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Alice Correia

Henry Moore

Two Piece Reclining Figure: Maquette No.4 1961

Bronze

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.9

Henry Moore

Two Piece Reclining Figure: Maquette No.4 1961

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Two Piece Reclining Figure No.5 probably originated from the plaster Two Piece Reclining Figure: Maquette No.3 1961 (fig.8), which was later cast in bronze. This maquette also shares a number of forms with Two Piece Reclining Figure: Maquette No.4 1961 (fig.9), in particular their leg sections, which have a similar shape and share the smooth surface that faces the torso piece. However, when seen from the side the torso section of Two Piece Reclining Figure: Maquette No.4 is rounder, forming a partially closed hollow near the base. This appears to have been rejected for the more open, upright pose of Maquette No.3. Having settled on one variation of the design, Moore would then have used the maquette as the template for his large-scale sculpture. By systematically charting and measuring specific points on its surface it was possible to enlarge the design while retaining its precise proportions. This process was probably carried out in the White Studio or, depending on the weather, in the grounds of Hoglands. Made in 1961, the date of this maquette demonstrates how Moore’s sculptures were often developed over several years, with the final full-size bronze sculpture not completed until 1964. Much of the preliminary plaster enlargement work would have been undertaken by one or more of Moore’s sculpture assistants, who in 1962–4 included Goeffrey Greetham, Robert Holding, Derek Howarth, Roland Piché, Ron Robertson-Swann, Clive Sheppard, Hylton Stockwell, Isaac Witkin and Yardini Yeheskiel.

In order to make the full-size plaster from which the bronze was cast, Moore and his assistants would have initially constructed an armature to the required size and rough shape for each section of the sculpture. The armature would have been made up of numerous lengths of wood and then draped in scrim, a bandage like fabric. Layers of plaster could be applied to the structure, while the interior of the armature remained hollow. Moore’s assistants would have applied and built up layers of plaster over the armature and scrim until only a short section of each armature rod was exposed (fig.10).

The armature did not only serve a structural purpose; the end of each rod corresponded to a point on the surface of the sculpture as measured and multiplied from the maquette. Moore explained that ‘once they [the assistants] have brought the work within an inch or so of the measurements I intend it to be, I take it over, and then it becomes a thing I’m working on as it would if I had brought it to that stage myself’.5 During the final stage of working on the plaster Moore began to work into the surface of the sculpture. Different marks and textures could be achieved depending on the varying wetness of the plaster as it dried. Moore found plaster to be a very useful material because it could be ‘both built up, as in modeling, or cut down, in the way you carve stone or wood’.6

The surface of the plaster was captured in the casting process and an examination of the bronze surface of Two Piece Reclining Figure No.5 shows how Moore developed a range of textures using a number of different tools including fine points, graters and spatulas (fig.11). Fine horizontal lines texture the upper surface of the leg piece while deep gouges under the knees contribute to a weathered effect.

Photograph of completed full-size plaster version of Two Piece Reclining Figure No.5 1963–4

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.12

Photograph of completed full-size plaster version of Two Piece Reclining Figure No.5 1963–4

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

The finished full-size plaster was sent to the Noack Foundry in West Berlin to be cast in bronze. During the 1950s and early 1960s Moore used a number of different foundries in London and Paris, but started working with Noack in 1958 following an introduction by the dealer Harry Fischer.8 By the 1950s the Noack Foundry was regarded as one of the best foundries equipped to undertake large-scale bronze castings. Moore dealt with its owner Herman Noack directly and paid for the casting of his sculptures himself. In 1967 Moore stated: ‘I use the Noack foundry for casting most of my work because in my opinion, Noack is the best bronze founder I know ... Also, the Noack foundry is reliable in all ways – in keeping to dates of delivery – and in sustaining the quality of their work’.9

It is unclear whether the lost wax or sand casting method was used to cast this bronze sculpture. In either case, the foundry technicians would have needed to carve up the plaster original into smaller pieces from which moulds could be taken. These moulds would then have been filled with molten bronze. Once the bronze had hardened it could be removed to reveal one section of the sculpture. These would have to be welded together and the seams filed down until the joints between each section of the cast were practically imperceptible. However, casting seams sometimes become more prominent over time because of differences between the composition of the bronze and the metal used to weld the sections together. A horizontal seam can be seen on the shoulder area of the torso piece of Two Piece Reclining Figure No.5 (fig.13).

Detail of patina on Two Piece Reclining Figure No.5 1963–4, cast date unknown

Tate T02294

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.14

Detail of patina on Two Piece Reclining Figure No.5 1963–4, cast date unknown

Tate T02294

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Sources and themes

Henry Moore OM, CH 1898–1986

Two Piece Reclining Figure No.2 1960, cast 1961–2

Bronze

object: 1250 x 2900 x 1375 mm

Tate T00395

Purchased 1960

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.15

Henry Moore OM, CH

Two Piece Reclining Figure No.2 1960, cast 1961–2

Tate T00395

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

In 1933 and 1934 I made many sculptures composed of two, three and sometimes four pieces. They were done partly to concentrate on the distances between forms – but also to consider the shape of the spaces between forms. In doing these Reclining Figure sculptures (No.1 in 1959 and No.2 in 1960), it came naturally and without any conscious decision, that I made them in two separate pieces – the head-and-body end – and the leg-end. In both sculptures I realised that I was simplifying the essential elements of my reclining figure theme ... In many of my reclining figures the head-and-neck part of the sculpture, sometimes the torso part too, is upright, giving contrast to the horizontal direction of the whole sculpture. Also in my reclining figures, I have often made a sort of looming leg – the top leg in the sculpture projecting over the lower leg, which gives a sense of thrust and power – as a large branch of a tree might move outwards from the main trunk – or as a seaside cliff might overhang from below, if you are on the beach.

A great asset of sculpture in the round (as against relief sculpture or painting), is its possibility of an infinite number of different views, giving, in changing lights, a never ending interest and surprise. The two separated forms produce a greater variety of views from all aspects – for as you walk round the sculpture one form gets in front of the other, in ways that cannot be anticipated, resulting in many unexpected, unforeseen views. In that sense, I think these sculptures are more fully in the round than any previous work of mine. Being in two pieces the work separates itself from seeming to be only a representation of a reclining figure.11

A great asset of sculpture in the round (as against relief sculpture or painting), is its possibility of an infinite number of different views, giving, in changing lights, a never ending interest and surprise. The two separated forms produce a greater variety of views from all aspects – for as you walk round the sculpture one form gets in front of the other, in ways that cannot be anticipated, resulting in many unexpected, unforeseen views. In that sense, I think these sculptures are more fully in the round than any previous work of mine. Being in two pieces the work separates itself from seeming to be only a representation of a reclining figure.11

Henry Moore

Working Model for Reclining Figure (Lincoln Centre) 1963–5, cast date unknown

Tate T02295

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.16

Henry Moore

Working Model for Reclining Figure (Lincoln Centre) 1963–5, cast date unknown

Tate T02295

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Moore rarely made sculptures specifically for a new project or commission. Instead he would invite the commissioning parties to choose from a selection of maquettes or mid-sized working models already in development. In this way Moore was able to develop his sculpture to his own specifications without having to modify his vision for others. By the time Moore began work on Two Piece Reclining Figure No.5 he had already completed four two-piece reclining figures and had amassed numerous maquettes and drawings that explored the spatial potential of dividing the human figure into multiple parts.

Henry Moore

Four-Piece Composition: Reclining Figure 1934

Cumberland alabaster on a Purbeck marble base

175 x 457 x 203 mm

Tate T02054

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.17

Henry Moore

Four-Piece Composition: Reclining Figure 1934

Tate T02054

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Moore also found that dividing the body into separate components released it from the immediate constraints of naturalistic representation. In pieces, the body could be more easily modified to incorporate and suggest foreign forms, such as geological formations and landscapes. Moore’s interest in landscapes and natural forms dates back to the late 1920s when he started collecting pebbles, shells and bones, and his sketchbooks from the early 1930s contain studies of these objects that have been altered to evoke human characteristics. Moving to Hoglands in 1941 allowed Moore’s collection of natural forms to grow, and he developed a particular interest in the flint stones ploughed up in the adjoining farmer’s field. Arranging and displaying these stones in his studio, Moore developed what he called a ‘form-knowledge’ of naturally occurring shapes, which he was then able to utilise imaginatively in his sculptural work.

The critic Donald Hall proposed in 1966 that, in addition to Moore’s sculptures from the 1930s, the forms of Two Piece Reclining Figure No.5 may have been informed by the shape of Adel Crag, a large outcrop of rock on Adel Moor, near Leeds. Hall described this natural formation as comprising ‘two huge rocks ... one is narrow and vertical; the other is split, enormous and jagged’, and suggested that it was difficult to look at Adel Crag without seeing a Henry Moore sculpture.18 Moore had visited the rock formation as a child and claimed that the experience left an indelible mark on his appreciation of natural forms.19

Moore’s preoccupation with the reclining female figure has been explained by numerous critics as an attempt to present an archetypal, or original and universally legible representation of the human form.20 Although the critic Albert Elsen observed that Moore was not comfortable with the term ‘archetype’ being applied to his work, Moore nonetheless agreed that he sought to create work that was universally recognisable.21 He recalled that, ‘There are fundamental ideas of shape or form that are natural to humans. These are not philosophical ideas I am dealing with. It’s the way we are made as people. It is comparing yourself with what you are making. The human figure is fundamentally the same’.22 This concern for the universality inherent in certain forms, and particularly those anchored in an understanding of the human body, concurred with the concept of transcendental universalism advocated by Moore’s life-long supporter and collaborator Herbert Read. In 1953 Read noted that ‘in modern Europe we cannot avoid certain humanitarian preoccupations ... The modern sculptor, therefore, more naturally seeks to interpret human form’.23 However, Read asserted that Moore distinguished himself from his contemporaries by relating ‘the human form to certain universal forms which may be found in nature’.24 By uniting features of the human body and natural forms, Moore was able to break free from what Read saw as the ‘false imprisonment’ of mimetic representation. Read supported his interpretation with Moore’s 1934 statement, originally published in Unit One:

Because a work of does not aim at reproducing natural appearances it is not, therefore, an escape from life – but may be a penetration into reality, not a sedative or drug, not just the exercise of good taste, the provision of pleasant shapes and colours in a pleasing combination, not a decoration to life, but an expression of the significance of life, a stimulation to greater effort of living.25

These beliefs underpinned Moore’s later work and anticipated his comment, made in 1967, that when looking for human resonances in natural forms ‘taste is not the guide. I’m not interested in the niceties of a shape’.26 By breaking down the body into distinct parts derived from natural forms, Moore sought to identify the figure with the earth, and humanity with its environment, expressing their union in an ‘organic whole’.27

Prior to entering the Tate collection Two Piece Reclining Figure No.5 was exhibited at the Sculpture in the Open Air exhibition at Battersea Park, London, in 1966. Moore had exhibited in each of the six open air sculpture exhibitions held in London since 1948, believing that ‘sculpture is an art of the open air; daylight – sunlight is necessary to it, and for me its best setting and complement is nature’.28 Writing in the exhibition catalogue, the curator Alan Bowness characterised Moore as an elder statesman among the younger exhibiting artists, noting that the younger generation, which included Anthony Caro, ‘do not share the same attitude to nature, and would on the whole prefer an urban and less a landscape setting – a bombed site rather than a garden’.29 Nonetheless, Bowness asserted that Moore’s attempt to penetrate reality through non-naturalistic forms had become a basic tenet of contemporary sculpture.

Henry Moore

Two Reclining Figures 1961

Graphite, wax crayon, coloured crayon, felt-tipped pen and watercolour wash on paper

613 x 524 x 31 mm

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Menor, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.18

Henry Moore

Two Reclining Figures 1961

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Menor, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

The Henry Moore Gift and loan to Kenwood House

Two Piece Reclining Figure No.5 1963–4 on display on the lawn during the exhibition The Henry Moore Gift, Tate Gallery in 1978

Tate T02294

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.19

Two Piece Reclining Figure No.5 1963–4 on display on the lawn during the exhibition The Henry Moore Gift, Tate Gallery in 1978

Tate T02294

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

After the exhibition closed the sculpture was returned to Moore’s studio so that it could be fitted to a new bronze base. However, by January 1981 Tate’s conservator noted that this base was not strong enough to support the two bronze pieces, reporting that rainwater was collecting around the bottom of each piece because they had created concave depressions in the base.35 The plinth was reinforced in 1981 and remained on display in front of the Tate until 1983.

In the years following the eightieth birthday exhibition, Reid and the trustees decided to loan large-scale works to galleries across the country on a long-term basis rather than keep them in storage. Kenwood House, an English Heritage property, had requested the loan of a sculpture by Moore and following correspondence regarding the safety and security of the sculpture, Two Piece Reclining Figure No.5 was installed at Kenwood House in 1983 at a site selected by Moore.

In July 1992 Ian Dejardin, the assistant curator at Kenwood House, wrote to Tate reporting that:

The figure on the left can be easily rocked backward and forward, and this is done frequently when teenagers climb over the sculpture and when doing so the whole bronze base, on which the sculpture rests, can shift towards the edge of the stone plinth. The weight of the sculpt + climbers have in all probability contributed to the base becoming concave around the base of this sculpture where also the water accumulates. Consequently a welded joint on the base has opened in 2 places (3cm apart) on the vertical face with some loss of metal; the hairline cracks continue to the horizontal part where it opens into 2 directs [sic], and where there is now a difference in level.36

Following this report of serious damage caused by people climbing on the sculpture, Two Piece Reclining Figure No.5 was removed from Kenwood House in October 1992. It was sent to Maurice Singer Foundry in Basingstoke for major repairs and reinforcement to the plinth at the cost of approximately £3,500. Following the sculpture’s reinstallation at Kenwood House in 1993, Tate discussed with English Heritage how to prevent such damage reoccurring. At first English Heritage increased invigilation of the sculpture and erected a ‘Do Not Climb’ sign. Tate favoured the erection of a fence around the sculpture, but according to records held in Tate’s Conservation Department there were ‘objections from English Heritage and the public to a fence being erected on the grounds of aesthetics rather than conservation ethics, [which] led to a hedge being the agreed preventative measure. However, it took 3 years of meetings and correspondence before the hedge was planted’.37 The low hedge was finally planted in 1996 but was unsuccessful as a deterrent for members of the public who wanted to climb on the sculpture. In October 2000 conservator Jehannine Mauduech noted that the hedge was trampled, visible footprints and scratches had appeared on the sculpture and the torso piece was rocking.38

Following Mauduech’s report moves were made to erect a tall fence around the sculpture; planning permission was sought from Camden Council in December 2000 and the following spring a plinth-height perimeter fence was installed around the sculpture. Although the fence has been largely successful in deterring climbers, graffiti has occasionally been found on the surface of the sculpture (fig.20).

Two Piece Reclining Figure No.5 was cast in an edition of three, plus one artist’s copy. Tate’s cast is numbered ‘3/3’. However, this numbering points to a discrepancy somewhere among the four casts of the sculpture. According to records held at the Henry Moore Foundation, edition one was sold to Ruhrfestspielhaus, Recklinghausen, number two to Agnelli, Turin, and number three to the Louisiana Museum, Humlebaek. Moore’s artist’s cast, which would usually be numbered ‘0/3’, is identified as Tate’s cast.39 It is unclear whether the casts belonging to Moore and the Louisiana Museum were accidentally swapped, but it was supposedly the artist’s cast that Moore gifted to Tate in 1978. The examples sold to Ruhrfestspielhaus and the Louisiana Museum remain in those collections, but the whereabouts of the example sold to Agnelli, Turin, is unknown. The full-size plaster is held in the collection of the Henry Moore Foundation.

Alice Correia

August 2013

Notes

Henry Moore cited in Albert Elsen, ‘Henry Moore’s Reflections on Sculpture’, Art Journal, vol.26, no.4, summer 1967, p.355.

Henry Moore in ‘Henry Moore Talking to David Sylvester’, 7 June 1963, transcript of Third Programme, BBC Radio, broadcast 14 July 1963, Tate Archive TGA 200816, p.18. (An edited version of this interview was published in Listener, 29 August 1963, pp.305–7.)

Henry Moore cited in Donald Hall, ‘Henry Moore: An Interview by Donald Hall’, Horizon, November 1960, reprinted in Alan Wilkinson (ed.), Henry Moore: Writings and Conversations, Aldershot 2002, p.226.

Henry Moore, ‘Two-Piece Reclining Figures 1959 and 1960’, artist’s statement sent to Martin Butlin, 13 April 1961, Tate Artist Catalogue File, Henry Moore, A23945, reprinted in Mary Chamot, Dennis Farr and Martin Butlin, Tate Gallery Catalogue: The Modern British Paintings, Drawings and Sculpture, London 1964, p.28.

Richard Morphet, ‘T.2287 Two-Piece Reclining Figure No.3’, in The Tate Gallery 1978–80: Illustrated Catalogue of Acquisitions, London 1981, p.130.

Henry Moore, ‘Statement for Unit One’, in Herbert Read (ed.), Unit One: The Modern Movement in English Architecture, Painting and Sculpture, London 1934, pp.29–30, cited in Read 1953, p.207.

Henry Moore, ‘Sculpture for Landscape’, in Selection, Winchester 1962, pp.12, 15, reprinted in Wilkinson 2002, p.245.

Alan Bowness, Greater London Council Exhibition, Battersea Park, London 1966, exhibition catalogue, Battersea Park, London 1966, unpaginated.

These figures are based on those listed in a memo in the exhibition’s records; see Tate Public Records TG 92/344/2.

‘T.2294 Henry Moore, Two Piece Reclining Figure No.5 (1963–4)’, Tate Conservation Report, January 1981, Tate Conservation Records.

Ian Dejardin, ‘Henry Moore Bronze Sculpture in Kenwood Park’, memo to Tate, 2 July 1992, Tate Conservation Records.

Related essays

- Henry Moore: The Plasters Anita Feldman

- Henry Moore and the Welfare State Dawn Pereira

- Henry Moore's Approach to Bronze Lyndsey Morgan and Rozemarijn van der Molen

Related material

-

Photograph

-

Photograph

How to cite

Alice Correia, ‘Two Piece Reclining Figure No.5 1963–4, cast date unknown by Henry Moore OM, CH’, catalogue entry, August 2013, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015, https://www