Henry Moore OM, CH Two Piece Reclining Figure No.3 1961, cast date unknown

Image 1 of 14

-

Henry Moore OM, CH, Two Piece Reclining Figure No.3 1961, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Two Piece Reclining Figure No.3 1961, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Two Piece Reclining Figure No.3 1961, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Two Piece Reclining Figure No.3 1961, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Two Piece Reclining Figure No.3 1961, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Two Piece Reclining Figure No.3 1961, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Two Piece Reclining Figure No.3 1961, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Two Piece Reclining Figure No.3 1961, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Two Piece Reclining Figure No.3 1961, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Two Piece Reclining Figure No.3 1961, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Two Piece Reclining Figure No.3 1961, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Two Piece Reclining Figure No.3 1961, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Two Piece Reclining Figure No.3 1961, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Two Piece Reclining Figure No.3 1961, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Two Piece Reclining Figure No.3 1961, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Two Piece Reclining Figure No.3 1961, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Two Piece Reclining Figure No.3 1961, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Two Piece Reclining Figure No.3 1961, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Two Piece Reclining Figure No.3 1961, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Two Piece Reclining Figure No.3 1961, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Two Piece Reclining Figure No.3 1961, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Two Piece Reclining Figure No.3 1961, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Two Piece Reclining Figure No.3 1961, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Two Piece Reclining Figure No.3 1961, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Two Piece Reclining Figure No.3 1961, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Two Piece Reclining Figure No.3 1961, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Two Piece Reclining Figure No.3 1961, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Two Piece Reclining Figure No.3 1961, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH,

Two Piece Reclining Figure No.3

1961, cast date unknown

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

The space separating the upper body and legs of this reclining figure serves to disconnect the body into singular parts, and has encouraged commentators to align this sculpture with Moore’s interest in geological formations and impressionist paintings of cliffs.

Henry Moore OM, CH 1898–1986

Two Piece Reclining Figure No.3

1961, cast date unknown

Bronze

1585 x 2800 x 1370 mm

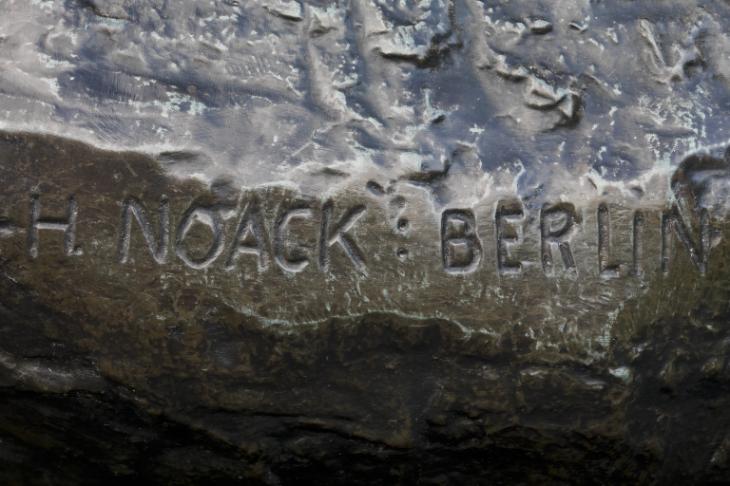

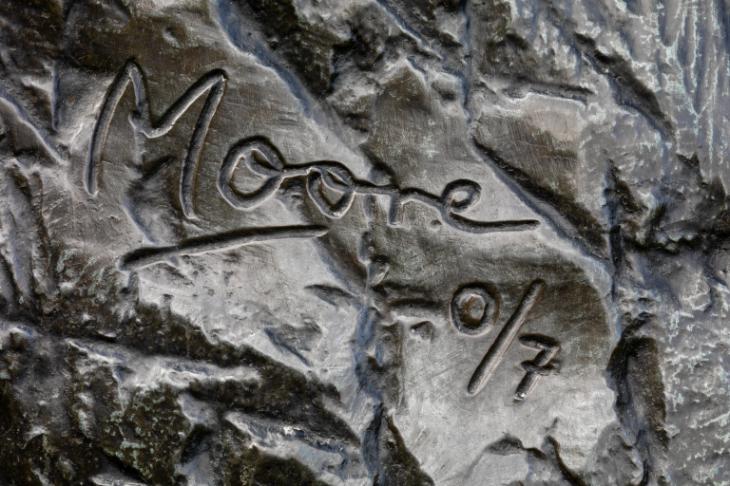

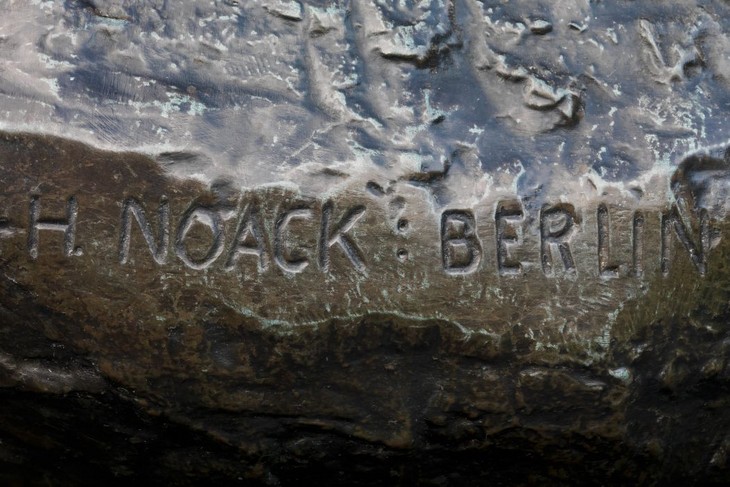

Inscribed ‘Moore 0/7’ and stamped with foundry mark ‘H. NOACK BERLIN’ on side of legs

Presented by the artist 1978

Artist’s copy aside from an edition of 7

T02287

Two Piece Reclining Figure No.3

1961, cast date unknown

Bronze

1585 x 2800 x 1370 mm

Inscribed ‘Moore 0/7’ and stamped with foundry mark ‘H. NOACK BERLIN’ on side of legs

Presented by the artist 1978

Artist’s copy aside from an edition of 7

T02287

Ownership history

Presented by the artist to Tate in 1978 as part of the Henry Moore Gift.

Exhibition history

1961–2

Henry Moore: Sculpture and Drawings 1927–1959, British Council touring exhibition: Galleria Nazionale de Arte Moderna, Rome, January–February 1961; Musée Rodin, Paris, March–April 1961; Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, June–July 1961; Akademie der Künste, Berlin, July–September 1961; Akademie der Bildenden Künste, Vienna, September–October 1961; Louisiana Museum, Humlebaek, December 1961–January 1962.

1967

Henry Moore, Mappin Art Gallery, Sheffield, July–September 1967, no.6.

1971

Henry Moore: Sculpture, Drawings, Graphics, Turnpike Gallery, Leigh, November–December 1971, no.10.

1976

The Work of the British Sculptor Henry Moore, Zürcher Forum, Zürich, June–August 1976, no.64.

1978

The Henry Moore Gift, Tate Gallery, London, June–August 1978, no number.

2004

Henry Moore at Dulwich Picture Gallery, Dulwich Picture Gallery, London, May–September 2004, no.34.

2005

Henry Moore y México, Museo Dolores Olmedo, Mexico City, June–October 2005, no.45.

References

1965

Herbert Read, Henry Moore: A Study of His Life and Work, London 1965, pp.229–32

(?another cast reproduced pl.217).

(?another cast reproduced pl.217).

1965

Alan Bowness (ed.), Henry Moore. Volume 3: Sculpture and Drawings 1955–64, London 1965 (?another cast reproduced pls.129–34).

1966

Philip James (ed.), Henry Moore on Sculpture, London 1966, pp.266–74.

1968

David Sylvester, Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Tate Gallery, London 1968, pp.93–4.

1968

John Hedgecoe (ed.), Henry Moore, London 1968, pp.338, 349.

1973

John Russell, Henry Moore, London 1973, reproduced pls.119–20.

1978

The Henry Moore Gift, exhibition catalogue, Tate Gallery, London 1978, reproduced p.46.

1979

Alan G. Wilkinson, The Moore Collection in the Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto 1979, p.172 (original plaster reproduced pl.151).

1981

Richard Morphet, ‘T.2287 Two-Piece Reclining Figure No.3’, in The Tate Gallery 1978–80: Illustrated Catalogue of Acquisitions, London 1981, reproduced pp.129–30.

1982

Important Sculptures by Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Marlborough Gallery, New York 1982 (another cast reproduced on front cover).

1987

Henry Moore and Landscape, exhibition catalogue, Yorkshire Sculpture Park, West Bretton 1987 (another cast and detail reproduced p.24).

1996

Elain Harwood, Something Worth Keeping: Post-War Architecture in England, exhibition catalogue, Royal Institute of British Architects, London 1996, p.13.

1998

Margaret Garlake, New Art / New World: British Art in Postwar Society, New Haven and London 1998, p.229.

2004

Henry Moore at Dulwich Picture Gallery, exhibition catalogue, Dulwich Picture Gallery, London 2004, reproduced p.86.

2005

Henry Moore y México, exhibition catalogue, Museo Dolores Olmedo, Mexico City 2005, reproduced p.75.

Technique and condition

This large, two-part bronze sculpture of a reclining figure is mounted on a smooth rectangular bronze base, probably by bolts threaded from underneath. The sculpture would have been cast from a plaster original, which Moore would have made by applying successive layers of wet plaster over a supportive armature. This armature was most likely constructed from lengths of wood along with chicken wire and scrim bandages to help define the initial form. Moore worked into the plaster at various stages of the setting process, making marks that were carried over into the bronze. Striations in the bronze surface would have initially been made in the wet plaster whereas chisel marks would have been created when the plaster was dry (fig.1). Other marks evidence Moore’s use of a surform tool or grater when the plaster was ‘cheese hard’ (fig.2).

Detail of head of Two Piece Reclining Figure No.3, cast date unknown (rear view)

Tate T02287

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.1

Detail of head of Two Piece Reclining Figure No.3, cast date unknown (rear view)

Tate T02287

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Detail of legs of Two Piece Reclining Figure No.3 1961, cast date unknown, showing surface texture

Tate T02287

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.2

Detail of legs of Two Piece Reclining Figure No.3 1961, cast date unknown, showing surface texture

Tate T02287

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

When the plaster had fully hardened a mould was taken from it and used to make a hollow cast in bronze. Close examination of the surface reveals the presence of casting investment in crevices in the surface of the sculpture, which suggest that the sculpture was cast using the lost wax method (fig.3). This would have required the foundry to cast the bronze in multiple sections before welding them together to form the whole. The welds were carefully filed down and textured with punch tools to match the height and appearance of the original surface, a process known as ‘chasing’. An example of this can be seen on the figure’s right shoulder. The cast surface of the bronze has otherwise been retained to preserve the detail of Moore’s heavily textured original plaster.

Detail of casting investment in Two Piece Reclining Figure No.3 1961, cast date unknown

Tate T02287

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.3

Detail of casting investment in Two Piece Reclining Figure No.3 1961, cast date unknown

Tate T02287

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Once the bronze had been cleaned and chased it would have been chemically patinated to colour the surface and help disguise welds and repairs. The patina solution would have been brushed and stippled onto the surface of the bronze, causing a reaction with the metal that produced coloured compounds. In this case the sculpture appears to have been originally patinated dark brown. However, this colour has been altered by exposure to the weather, as demonstrated by pale green areas appearing on its raised surfaces.

Tate’s outdoor sculptures are maintained on a yearly basis. This involves checking them for any signs of deterioration, washing them to remove dirt and bird lime, and usually applying a clear wax to their surfaces to protect them from the weather.

Detail of artist's signature and edition number on Two Piece Reclining Figure No.3 1961, cast date unknown

Tate T02287

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.4

Detail of artist's signature and edition number on Two Piece Reclining Figure No.3 1961, cast date unknown

Tate T02287

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Detail of foundry stamp on Two Piece Reclining Figure No.3 1961, cast date unknown

Tate T02287

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.5

Detail of foundry stamp on Two Piece Reclining Figure No.3 1961, cast date unknown

Tate T02287

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

The artist’s signature and edition number, ‘Moore 0/7’ (fig.4), and the foundry mark, ‘H. NOACK: BERLIN’ (fig.5), appear on the rear side of the figure’s legs.

Lyndsey Morgan

March 2013

How to cite

Lyndsey Morgan, 'Technique and Condition', March 2013, in Alice Correia, ‘Two Piece Reclining Figure No.3 1961, cast date unknown by Henry Moore OM, CH’, catalogue entry, July 2012, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015, https://wwwEntry

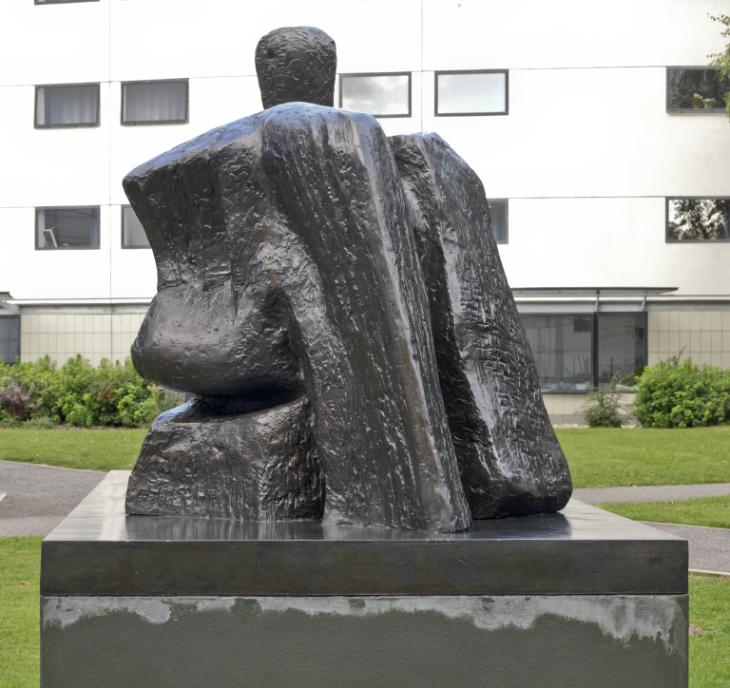

Two Piece Reclining Figure No.3 is the third of four large-scale two-part sculptures made by Henry Moore between 1959 and 1961.1 This series represented a major development in Moore’s treatment of the reclining figure, a subject that preoccupied him throughout his career. In this work the bronze figure has been divided into two separate parts positioned on a base: one rises vertically to a central point and may be understood to represent a head, shoulders and torso, while the other takes the form of a solid block marked by deep gouges and occupies the position of the legs. The front of the sculpture is usually understood to be the view where the taller upper body section is on the left and the leg section on the right.

Detail of head of Two Piece Reclining Figure No.3 1961, cast date unknown (front view)

Tate T02287

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.1

Detail of head of Two Piece Reclining Figure No.3 1961, cast date unknown (front view)

Tate T02287

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Detail of head of Two Piece Reclining Figure No.3, cast date unknown (rear view)

Tate T02287

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.2

Detail of head of Two Piece Reclining Figure No.3, cast date unknown (rear view)

Tate T02287

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

The head of the figure is rendered as a thin, upright protrusion emerging from a broad, smoothly rounded horizontal ridge representing shoulders. The only suggestion of a facial feature is a small, round indentation in the front (fig.1), while the back of the head is marked by several sharp ridges and a deep gouge (fig.2). The right shoulder extends down to form a recognisable arm shape, bent at the elbow so that the forearm rests on the base. The curve of this arm is accentuated by a hole that pierces the centre of the torso, while a block-like hand at the end of this arm connects to another horizontal appendage that might be either the left arm or abdomen. Although the form contains rounded surfaces, from the rear this upper body can be seen to feature a number of straight edges (fig.3). As well as the almost square-shaped hole that runs through the torso, a deep recess with straight edges marks a space between the shoulders, while both flanks appear to extend vertically downwards before turning at right-angles with the base.

The outline of the other piece also equates to a roughly shaped cuboid form. It is formed of one solid piece of bronze, and features deep vertical gouges and channels that cut into its core. From the rear two individual legs may be identified, separated by a deep incision (fig.4). Their diagonal orientation suggests that they may be calves of legs bent at the knees, although the irregular outline of this block makes them hardly legible as such.

Two Piece Reclining Figure No.3 1961, cast date unknown (rear view)

Tate T02287

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.4

Two Piece Reclining Figure No.3 1961, cast date unknown (rear view)

Tate T02287

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Two Piece Reclining Figure No.3 1961, cast date unknown (rear angled view)

Tate T02287

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.5

Two Piece Reclining Figure No.3 1961, cast date unknown (rear angled view)

Tate T02287

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Although the side of the sculpture from which the figure’s arm is visible is usually presented and photographed as its front, Moore consciously sculpted the forms to be experienced in the round. Indeed, the need to make imaginative leaps in order to establish a coherent image of the body appears to have shaped a number of Moore’s formal decisions. The gap separating the two parts of this sculpture and the use of crevices and hollows point to the importance of negative space as something that unites as well as divides the various elements of the sculpture. For example, from the rear the arrangement of forms is perhaps more easily recognisable as a single figure, in that the almost horizontal protrusion from the top of the legs appears to bridge or lock the gap between this section and the upper body (fig.5). It is also from this angle that the figure may be identified as female, for the left shoulder may also represent a breast at the same height as the protrusion from the sternum.

From plaster to bronze

Moore began developing ideas for two-piece reclining figures in 1959 with a series of small plaster maquettes. By the 1950s Moore had moved away from making preliminary drawings for his sculptures and had started making small three-dimensional models in clay, plaster, wax and plasticine. It is likely that he made the maquettes for his two-piece sculptures in the maquette studio on the grounds of his home, Hoglands, at Perry Green in Hertfordshire. This studio was lined with shelves displaying Moore’s ever growing collection of found bones, shells and pebbles, the shapes of which often served as starting points for Moore’s formal experiments in three dimensions. In 1968 Moore explained to the photographer John Hedgecoe:

I like this little studio. I am always very happy there. I like the disarray, the muddle and the profusion of possible ideas in it. It means that whenever I go there, within five minutes I can find something to do which may get me working in a way that I hadn’t expected and cause something to happen that I hadn’t foreseen.2

Henry Moore

Two Piece Reclining Figure: Maquette No.3 1961

Painted plaster

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Alice Correia

Fig.6

Henry Moore

Two Piece Reclining Figure: Maquette No.3 1961

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Alice Correia

Henry Moore

Two Piece Reclining Figure: Maquette No.1 1960

Bronze

Dallas Museum of Art

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.7

Henry Moore

Two Piece Reclining Figure: Maquette No.1 1960

Dallas Museum of Art

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

The maquette for Two Piece Reclining Figure No.3 (fig.6) was made in 1961. Some of the other maquettes for two-piece sculptures made around this time, such as Two Piece Reclining Figure: Maquette No.1 1960 (fig.7), were cast in bronze at their original size, but not all of them were scaled up into full size sculptures. Moore explained:

Sometimes I make ten or twenty maquettes for every one that I use in a large scale – the others may get rejected. If a maquette keeps its interest enough for me to want to realise it as a full-size final work, then I might make a working model in an intermediate size, in which changes will be made before going to the real, full-sized sculpture. Changes get made at all these stages.3

When Moore finished the maquette for Two Piece Reclining Figure No.3 he applied colour to the white plaster to gauge what it might look like in bronze. The maquette would then act as the template for the large-scale sculpture. By systematically measuring specific points on the surface of the maquette the design could be enlarged while retaining its original proportions. The enlargement process would probably have been carried out in the White Studio, also situated in the grounds of Hoglands, by Moore’s sculpture assistants, who in 1961 were Clive Sheppard and Bill Smith.

In order to make the full-size plaster from which the bronze was cast, Moore and his assistants would have initially constructed a wooden armature to the required size and shape for each section of the sculpture. The armatures were made up of numerous lengths of wood and possibly chicken wire, and then draped or wrapped in scrim, a bandage-like fabric. Layers of plaster could then be applied to the armature while its interior remained hollow.

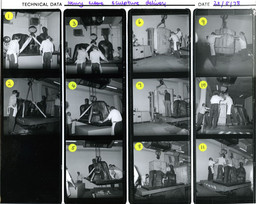

John Hedgecoe

Henry Moore working on the plaster torso section of Two Piece Reclining Figure No.3 1961

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.8

John Hedgecoe

Henry Moore working on the plaster torso section of Two Piece Reclining Figure No.3 1961

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

After it was finished the full-size plaster was sent to the Noack Foundry in West Berlin to be cast in bronze. During the 1950s and early 1960s Moore used a number of different foundries in London and Paris, but started working with Noack in 1958 following an introduction by the dealer Harry Fischer.6 By the 1950s Noack was regarded as one of the best foundries equipped to undertake large-scale bronze castings. Moore dealt with its owner Herman Noack directly and paid for the casting of his sculptures himself. In 1967 Moore stated: ‘I use the Noack foundry for casting most of my work because in my opinion, Noack is the best bronze founder I know ... Also, the Noack foundry is reliable in all ways – in keeping to dates of delivery – and in sustaining the quality of their work’.7

It is likely that Noack used the lost wax technique to cast the bronze sculpture. This would have required the foundry to carve up the plaster into sections and create moulds from each piece. The inside of each mould would then be ‘greased’ with a releasing agent before molten wax was poured into it. Once the wax had hardened it could be released from the mould, forming an exact replica of the sculpture in wax. The wax would then be encased in a hard refractory material, placed in a kiln and heated until it melted. Channels within the casing would allow the wax to drain away and, once empty, the cavity was filled with molten bronze. When the bronze had hardened its casing was removed, revealing a section of sculpture. After every piece of the sculpture had been cast in this way they would be welded together. Finally, the casting seams would have been filed down until the joints between each section of the cast were practically imperceptible.

After it was reassembled at the foundry the bronze sculpture was returned to Moore so that he could inspect its quality and make decisions about its patination. A patina is the surface colour of a sculpture and is usually achieved by applying chemical solutions to the bronze surface. In 1963 Moore stated that ‘I always patinate bronze myself’, going on to explain that since he had conceived the sculpture it would be unlikely that anyone else would be able to replicate the exact colour he wanted.8 Bronze is an alloy of copper and tin and the patina of bronze sculptures displayed outdoors changes over time due to reactions between the metal and chemicals in the air. Tate’s cast is a fairly uniform dark brown colour, which is maintained by regular waxing and cleaning. Nonetheless, periods of exposure to the weather have caused areas of pale green to appear on the sculpture’s surface.

Sources and development

During an interview in 1962, the year after Two Piece Reclining Figure No.3 was made, Moore stated:

The Two-Piece Reclining Figures must have been working around in the back of my mind for years, really. As long ago as 1934 I had done a number of smaller pieces composed of separate forms, two- and three-piece carvings in ironstone, ebony, alabaster and other materials. They were all more abstract than these. I don’t think it was a conscious or intentional thing for me to break up the figures in this way, but I suppose those earlier works from the thirties had something to do with it. I didn’t do any preliminary drawings for these. I wish now I had ... I did the first one in two pieces almost without intending to. But after I’d done it, then the second one became a conscious idea. I realised what an advantage a separated two-piece composition could have in relating figures to landscape. Knees and breasts are mountains. Once these two parts become separated you don’t expect it to be a naturalistic figure; therefore, you can justifiably make it like a landscape or a rock. If it is a single figure, you can guess what it’s going to be like. If it is in two pieces, there’s a bigger surprise, you have more unexpected views; therefore the special advantage over painting – of having the possibility of many different views – is more fully exploited.9

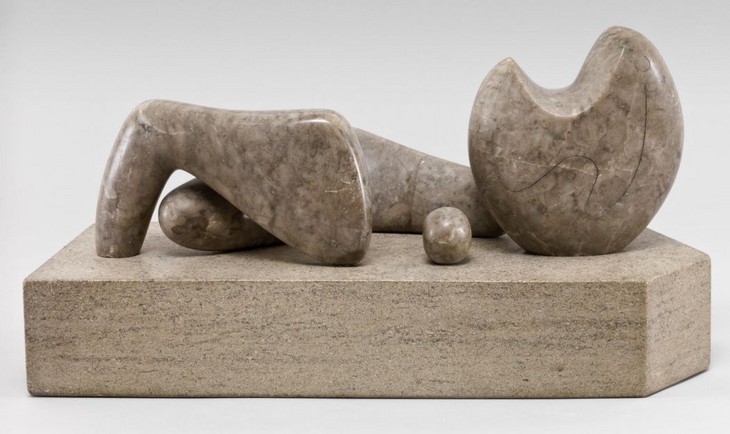

In his statement Moore acknowledged that although his first bronze two-piece reclining figure was made in 1959, his interest in broken or dismembered figures stemmed back to the early 1930s. One of Moore’s best known sculptures from that period is Four Piece Composition: Reclining Figure 1934 (fig.9), in which the reclining figure is separated into four distinct components spread out along a plinth. In 1968 Moore explained that in 1933–4 ‘I began separating forms from each other in order to be able to relate space and form together’.10 Although this retrospective explanation of the 1934 work may have been influenced by the two- and three-piece sculptures Moore was making at the time, it nonetheless suggests a degree of formal continuity between bodies of work made almost thirty years apart.

Henry Moore

Four-Piece Composition: Reclining Figure 1934

Cumberland alabaster on a Purbeck marble base

175 x 457 x 203 mm

Tate T02054

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.9

Henry Moore

Four-Piece Composition: Reclining Figure 1934

Tate T02054

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

When Moore began working on a much larger scale in the 1950s, his interest in the compositional potential of space developed to account for the viewer’s changing physical relationship to the object. He noted in 1968 that:

a sculpture in two pieces means that, as you walk round it, one form gets in front of the other in ways you cannot foresee ... The space between the two parts has to be exactly right. It’s as though one was putting together the fragments of a broken antique sculpture in which you have, say, only the knee, a foot and the head. In the reconstruction the foot would have to be the right distance from the knee, and the knee the right distance from the head, to leave room for the missing parts – otherwise you would get a wrongly proportioned figure.11

Moore’s comments illustrate how much attention he paid to the sense of scale and the bodily proportions of his figurative sculptures. Yet, as in many of Moore’s sculptures, the head of Two Piece Reclining Figure No.3 seems disproportionately small when compared to the bulky mass of the body. Moore explained this formal decision, stating that ‘actually, for me the head is the most important part of a piece of sculpture. It gives to the rest a scale, it gives to the rest a certain human poise, and meaning, and it’s because I think that the head is so important that often I reduce it in size to make the rest more monumental’.12

Henry Moore

Warrior with Shield 1953–4

Bronze on wood plinth

1530 x 660 x 830 mm

Birmingham Museums and Art Gallery

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.10

Henry Moore

Warrior with Shield 1953–4

Birmingham Museums and Art Gallery

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Moore also found that dividing the body into separate components released it from the immediate constraints of naturalistic representation. In pieces, the body could be more easily modified to incorporate and suggest foreign forms, such as geological formations and landscapes. Moore’s interest in landscapes and natural forms dates back to the late 1920s when he started collecting pebbles, shells and bones, and his sketchbooks from the early 1930s contain studies of these objects that have been altered imaginatively to evoke human characteristics.

Henry Moore

Reclining Woman (Mountains) 1930

Green Hornton stone

National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.11

Henry Moore

Reclining Woman (Mountains) 1930

National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

In a statement written in 1961 to Martin Butlin, Assistant Keeper of the Tate collection, Moore described his two-piece reclining figures:

in my reclining figures, I have often made a sort of looming leg – the top leg in the sculpture projecting over the lower leg, which gives a sense of thrust and power – as a large branch of a tree might move outwards from the main trunk – or as a seaside cliff might overhang from below, if you are on the beach.17

Moore’s description of the ‘projecting’ or ‘looming leg’, and the likeness he proposed between this feature and an overhanging cliff might illuminate the formal relationship established by the overhanging element in the leg piece of Two Piece Reclining Figure No.3. Indeed the analogy of a cliff leaning out over the sea has been productive for several writers on Moore’s work, including Herbert Read, Robert Melville and Alan Wilkinson, all of whom found parallels between his sculptural forms and the depiction of cliffs in paintings by Claude Monet and Georges Seurat.18 Seurat’s Le Bec du Hoc, Grandcamp 1885 (fig.12) was previously owned by Moore’s close friend, the art historian Kenneth Clark, and it is known that Moore saw it during his regular visits to Clark’s home.19

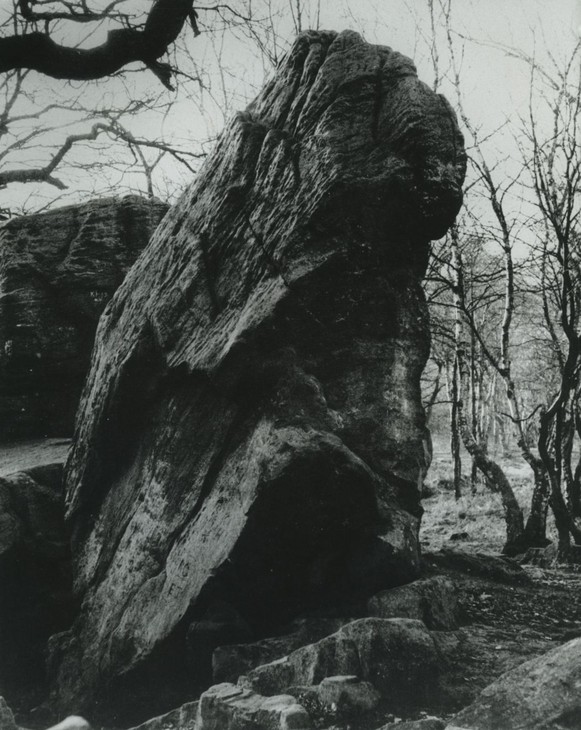

John Hedgecoe

Adel Crag

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.13

John Hedgecoe

Adel Crag

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

The critics Phillip James and Donald Hall have both proposed that, in addition to French impressionist paintings and Moore’s sculptures from the 1930s, the forms of Two Piece Reclining Figure No.3 may have been informed by the shape of Adel Crag, a large outcrop of rock on Adel Moor, near Leeds (fig.13). Hall described this natural formation as comprising ‘two huge rocks ... one is narrow and vertical; the other is split, enormous and jagged’, and suggested that it was difficult to look at Adel Crag without seeing a Henry Moore sculpture.20 Moore had visited the rock formation as a school child and claimed that the experience left an indelible mark on his appreciation of natural forms.21

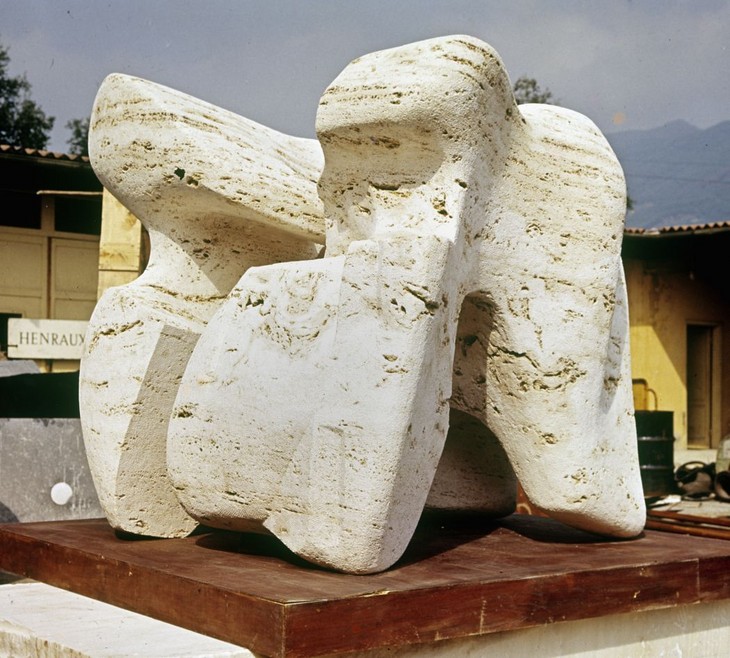

Henry Moore

Stone Memorial 1961–9

Travertine marble

National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.14

Henry Moore

Stone Memorial 1961–9

National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

In the exhibition catalogue for Moore’s retrospective exhibition at the Tate Gallery in 1968, the curator David Sylvester suggested an additional lens through which to interpret Moore’s two-piece reclining figures of 1959–61. Sylvester asserted that ‘on the whole this series presents by far the most specifically sexual imagery in Moore’s work’, explaining that what Moore described as a looming leg or tree branch could in fact be understood as a phallus.27 According to Sylvester, in the case of works such as Two Piece Reclining Figure No.3, ‘where there is no total equation of one part of the figure with the phallus, the torso part is likely to have a phallic appendage directed at the lower part. The appendage may in the first place be a truncated thigh’.28 Sylvester supported his claim with reference to a drawing made by Moore in 1961 called Two Reclining Figures (fig.15), which features a sketch in the lower half of the page that Sylvester associated with the act of fellatio: ‘the lower half is a huge mouth opened wide to receive an inexplicably elongated form sticking out of the torso’.29

Henry Moore

Two Reclining Figures 1961

Graphite, wax crayon, coloured crayon, felt-tipped pen and watercolour wash on paper

613 x 524 x 31 mm

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Menor, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.15

Henry Moore

Two Reclining Figures 1961

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Menor, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Henry Moore

Two Forms 1934

Pyinkado wood

279 x 546 x 308 mm

Museum of Modern Art, New York

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Fig.16

Henry Moore

Two Forms 1934

Museum of Modern Art, New York

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Sylvester’s account privileges the idea that the two parts of Moore’s Two Piece Reclining Figure No.3 interlock, evoking the mechanics of sexual intercourse. Nonetheless, he also acknowledged that ‘at the same time there is a contrary suggestion of a mother-and-child relationship’ as seen in the earlier Two Forms 1934 (fig.16).30 Moore had suggested that this earlier wooden sculpture could be ‘thought of as a Mother and Child ... The bigger form has a kind of pelvis shape in it and the smaller form is like the big head of a child’.31 With this in mind, the two horizontally protruding elements in Two Piece Reclining Figure No.3 could be regarded as a complementary pair rather than sections of a single figure. Indeed, as John Russell remarked in 1973, the division of the sculpture into two embodies ‘the idea of irreparable separation and loss which is fundamental to all human experience; and art’s highest function is fulfilled when we look again and realise that the two pieces have an intense and living relationship, as separate entities, which would be dulled and rendered inert if they were to be joined together’.32

The Henry Moore Gift

Installation view of the exhibition The Henry Moore Gift, Tate Gallery, 1978

Tate

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.17

Installation view of the exhibition The Henry Moore Gift, Tate Gallery, 1978

Tate

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

After the 1978 exhibition Tate decided that it should lend certain large-scale works from the Henry Moore Gift to regional galleries in the United Kingdom on a long-term basis.36 In August 1978 the Assistant Director of Tate Judith Jeffreys wrote to the collector Robert Sainsbury with a list of seven sculptures that had been identified as suitable for long-term loans. In 1977 Robert and Lisa Sainsbury had given their collection of modern and non-Western art to the University of East Anglia, Norwich, where it was housed in the purpose built Sainsbury Centre for Visual Art, designed by the architect Norman Foster. On receipt of Jeffrey’s letter, Robert Sainsbury personally selected Two Piece Reclining Figure No.3 for display outside the new gallery. By 27 September the loan had been agreed and quotes for transporting the sculpture from London to Norwich had been obtained.

In a letter to Norman Reid dated 28 November 1978 Moore stated, ‘I am pleased indeed that you agreed to lend Two Piece Reclining Figure No.3 to the Sainsbury centre. I went to Norwich with Bob and Lisa to help fix the exact siting, and I think it is going to look very nice there’.37 Moore had been friends with Robert and Lisa since the 1930s and was godfather to their son David. The Sainsburys had also been important and influential early collectors of Moore’s work and his drawings and sculptures were a fixture of their vast collection. Moore, the Sainsburys and Foster decided to position the sculpture in front of the large south window of the gallery on a lawn leading to a lake, and on 4 April 1979 it was installed on a plinth designed by Foster Associates in consultation with Moore. In 1989 the sculpture was moved from this location due to the construction of the Sainsbury Centre’s Crescent Wing extension, and was relocated in 2006 to a site between the gallery and Constable Terrace, the University’s hall of residence.

Two Piece Reclining Figure No.3 was cast in an edition of seven plus one artist’s copy. Tate’s bronze is numbered ‘0/7’, indicating that it is the artist’s copy. Other casts are held in the Gwendolyn Weiner Collection, on permanent loan to the Palm Springs Desert Museum, Palm Springs; Everson Museum of Art in Syracuse; SITOR in Turin; City of Gothenburg; Franklin D. Murphy Sculpture Garden at the University of California, Los Angeles; Brandon Estate in south London; and the Dallas Museum of Art.

Alice Correia

July 2012

Notes

The other works in this series are Two Piece Reclining Figure No.1 1959 (Chelsea School of Art, London), Two Piece Reclining Figure No.2 1960 (Tate T00395), and Two Piece Reclining Figure No.4 1961 (Wakefield Art Gallery).

Moore cited in Donald Hall, ‘Henry Moore: An Interview by Donald Hall’, Horizon, November 1960, reprinted in Alan Wilkinson (ed.), Henry Moore: Writings and Conversations, Aldershot 2002, p.226.

Moore cited in ‘Henry Moore Talking to David Sylvester’, 7 June 1963, transcript of Third Programme, BBC Radio, broadcast 14 July 1963, pp.3–4, Tate Archive TGA 200816.

Henry Moore cited in Hugh Burnett (ed.), Face to Face: Interviews with John Freeman, London 1964, p.34.

Henry Moore, ‘Two-Piece Reclining Figures 1959 and 1960’, artist’s statement sent to Martin Butlin, 13 April 1961, Tate Artist Catalogue File, Henry Moore, A23945, reprinted in Mary Chamot, Dennis Farr and Martin Butlin, Tate Gallery Catalogues: The Modern British Paintings, Drawings and Sculpture, London 1964, vol.2, p.28.

See Herbert Read, Henry Moore: A Study of His Life and Work, London 1965, p.227; Melville 1970, p.29; and Alan G. Wilkinson, Henry Moore Remembered: The Collection at the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto, Toronto 1987, p.193.

See John Hedgecoe (ed.), Henry Moore: My Ideas, Inspiration and Life as an Artist, London 1986, p.35.

See Peter Fuller, ‘Henry Moore: An English Romantic’, in Susan Compton (ed.), Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Royal Academy of Arts, London 1988, pp.37–44; and Christa Lichtenstern, Henry Moore: Work-Theory-Impact, London 2008, pp.207–13.

Related essays

- Ambivalence and Ambiguity: David Sylvester on Henry Moore Martin Hammer

- Henry Moore: The Plasters Anita Feldman

- Erich Neumann on Henry Moore: Public Sculpture and the Collective Unconscious Tim Martin

- Henry Moore's Approach to Bronze Lyndsey Morgan and Rozemarijn van der Molen

Related catalogue entries

Related material

-

Photograph

-

Photographic contact sheet

How to cite

Alice Correia, ‘Two Piece Reclining Figure No.3 1961, cast date unknown by Henry Moore OM, CH’, catalogue entry, July 2012, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015, https://www