Henry Moore OM, CH Recumbent Figure 1938

Image 1 of 15

-

Henry Moore OM, CH, Recumbent Figure 1938© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Recumbent Figure 1938© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Recumbent Figure 1938© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Recumbent Figure 1938© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Recumbent Figure 1938© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Recumbent Figure 1938© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Recumbent Figure 1938© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Recumbent Figure 1938© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Recumbent Figure 1938© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Recumbent Figure 1938© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Recumbent Figure 1938© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Recumbent Figure 1938© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Recumbent Figure 1938© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Recumbent Figure 1938© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Recumbent Figure 1938© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Recumbent Figure 1938© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Recumbent Figure 1938© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Recumbent Figure 1938© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Recumbent Figure 1938© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Recumbent Figure 1938© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Recumbent Figure 1938© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Recumbent Figure 1938© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Recumbent Figure 1938© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Recumbent Figure 1938© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Recumbent Figure 1938© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Recumbent Figure 1938© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Recumbent Figure 1938© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Recumbent Figure 1938© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Recumbent Figure 1938© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Recumbent Figure 1938© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH,

Recumbent Figure

1938

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

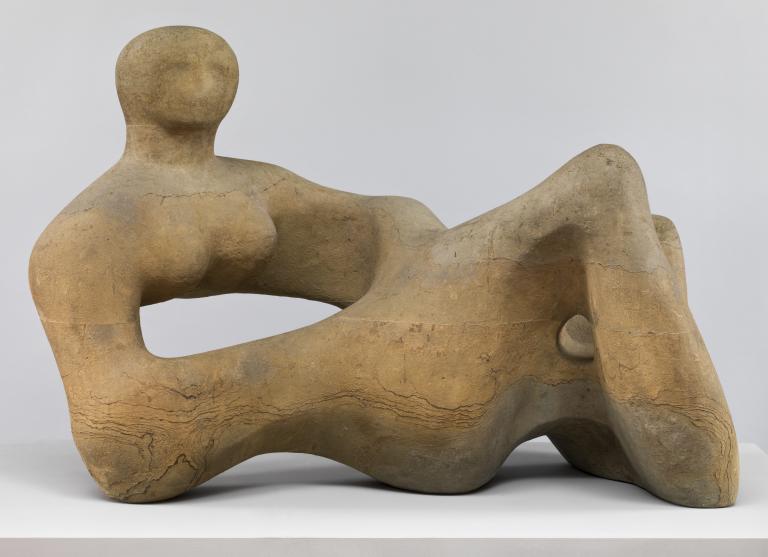

At the time it was made Recumbent Figure was Moore’s largest stone sculpture, commissioned by the architect Serge Chermayeff to stand on the terrace of his home in Sussex. Carved in English stone the reclining female figure resembles an undulating landscape and points to Moore’s interest in the soft, organic forms that featured in the work of Pablo Picasso and Jean Arp.

Henry Moore OM, CH 1898–1986

Recumbent Figure

1938

Green Hornton stone

889 x 1327 x 737 mm

Presented by the Contemporary Art Society 1939

N05387

Recumbent Figure

1938

Green Hornton stone

889 x 1327 x 737 mm

Presented by the Contemporary Art Society 1939

N05387

Ownership history

Acquired by Serge Chermayeff, Bentley Wood, Halland, Sussex, in 1938; purchased by the artist in February 1939; sold to the Contemporary Art Society in March 1939 for presentation to the Tate Gallery in April 1939.

Exhibition history

1939–40

Exhibition of Contemporary British Art, organised by British Council, New York World’s Fair, April–October 1939; April–October 1940, no.5.

1944

Art in Progress, Museum of Modern Art, New York, May–October 1944.

1948

Sculpture at Battersea Park, Battersea Park, London, May–September 1948, no.30.

1949–50

Henry Moore, British Council touring exhibition: Palais des Beaux-Arts, Brussels, October 1949; Musée d’art moderne, Paris, December 1949; Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, January 1950; Hamburger Kunsthalle, Hamburg, March 1950; Städtische Kunstsammlungen, Düsseldorf, May 1950; Kunsthalle Berne, Berne, June–July 1950, no.35.

1951

Sculpture and Drawings by Henry Moore, Tate Gallery, London, May–July 1951, no.109.

1960

Contemporary Art Society 50th Anniversary Exhibition: The First Fifty Years 1910–1960, Tate Gallery, London, April–May 1960, no.192.

1968

Henry Moore, Tate Gallery, London, July–September 1968, no.42.

1976

Sculpture for the Blind, Tate Gallery, London, November–December 1976, no number.

1977

Henry Moore: Sculptures et dessins, Musée de l’Orangerie des Tuileries, Paris, May–August 1977, no.31.

1978

The Henry Moore Gift, Tate Gallery, London, June-August 1978.

1979–80

Thirties: British Art and Design before the War, Hayward Gallery, London, October 1979–January 1980, p.42, no.6.57.

1981

Henry Moore: Sculptures, Drawings, Graphics 1921–1981, Palacio de Velázquez, Palacio de Cristal, Parque de El Retiro, Madrid, May–August 1981, no.120.

1981

British Sculpture in the Twentieth Century. Part One: Image and Form 1901–50, Whitechapel Art Gallery, London, September–November 1981, no.130.

1988

Henry Moore, Royal Academy of Arts, London, September–December 1988, no.34.

2010–11

Henry Moore, Tate Britain, London, February–August 2010; Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, October 2010–February 2011; Leeds Art Gallery, Leeds, March–June 2011; no.79.

References

1944

Herbert Read (ed.), Henry Moore: Sculpture and Drawings, London 1944, reproduced pls.43a–43b.

1944

Art in Progress, exhibition catalogue, Museum of Modern Art, New York 1944, p.139, reproduced p.222.

1946

Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Museum of Modern Art, New York 1946, reproduced p.48.

1947

Philip Hendy, ‘Sculpture in the Open Air’, Britain Today, no.147, July 1948, pp.14–17.

1948

David Sylvester, ‘The Evolution of Henry Moore’s Sculpture: I’, Burlington Magazine, vol.90, no.543, June 1948, p.164.

1948

Robert Melville, ‘Contemporary Sculpture in the Open Air’, Listener, 10 June 1948, pp.942–3.

1951

Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Tate Gallery, London 1951, p.14, reproduced pl.35.

1953

E.H. Ramsden, Sculpture: Theme and Variations, London 1953, p.40, reproduced pl.86.

1955

George Wingfield Digby, Meaning and Symbol in Three Modern Artists: Edvard Munch, Henry Moore, Paul Nash, London 1955, pp.61–105, reproduced pl.22.

1956

Kenneth Clark, The Nude, London 1956, pp.356–7, reproduced pl.292.

1957

David Sylvester (ed.), Henry Moore. Volume 1: Complete Sculpture 1921–48, London 1957, p.12, no.191, reproduced p.112–13.

1961

John Russell, Henry Moore: Stone and Wood Carvings, exhibition catalogue, Marlborough Fine Art, London 1961, p.19.

1965

Herbert Read, Henry Moore: A Study of His Life and Work, London 1965, pp.128–33.

1965

David Thompson, ‘Recumbent Figure by Henry Moore’, Listener, 25 November 1965, p.860–1.

1972

William Barrett, Time of Need: Forms of Imagination in the Twentieth Century, New York 1972, reproduced p.168.

1972

Elda Fezzi, Henry Moore, London 1972.

1973

Henry J. Seldis, Henry Moore in America, New York 1973, p.50.

1973

John Russell, Henry Moore, 1963, revised edn, London 1973, pp.94–8, reproduced pp.100–1.

1976

Sculpture for the Blind, exhibition catalogue, Tate Gallery, London 1976.

1976

Harold Osborne, ‘Two at the Tate’, Arts Review, 12 November 1976, reproduced.

1977

Henry Moore: Sculptures et dessins, exhibition catalogue, Musée de l’Orangerie des Tuileries, Paris 1977, reproduced p.78.

1977

Alan Wilkinson, The Drawings of Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Tate Gallery, London 1977, reproduced fig.34.

1978

Michael Clarke, ‘Figures in a Landscape’, Times Educational Supplement, 7 July 1978, p.28.

1979

Thirties: British Art and Design before the War, exhibition catalogue, Hayward Gallery, London 1979, reproduced p.42.

1981

Christa Lichtenstern, ‘Henry Moore and Surrealism’, Burlington Magazine, vol.123, no.944, November 1981, pp.644–58.

1986

The Contemporary Art Society 1910–1985, London 1986, reproduced p.21.

1987

Roger Berthoud, The Life of Henry Moore, London 1987, p.172, reproduced.

1988

Susan Compton (ed.), Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Royal Academy of Arts, London 1988, pp.186–7, reproduced no.34.

1988

The Tate Gallery 1986–88: Illustrated Biennial Report, London 1988, p.27.

1989

Jane Brown, The Art and Architecture of English Gardens, London 1989, pp.179–97.

1991

British Contemporary Art 1910–1990: Eighty Years of Collecting by The Contemporary Art Society, London 1991, pp.69–80, reproduced.

1992

Monica Bohm-Duchen, The Nude, London 1992, reproduced p.52.

1998

Frances Spalding, The Tate: A History, London 1998, reproduced p.75.

1999

Tessa Jackson, ‘Recumbent Figure 1938, Henry Moore’, in Jackie Heuman (ed.), Material Matters: The Conservation of Modern Sculpture, London 1999, pp.62–71.

1999

Modern Britain 1929–1939, exhibition catalogue, Design Museum, London 1999, pp.18–39, reproduced.

2001

Alan Powers, Serge Chermayeff: Designer, Architect, Teacher, London 2001, pp.128–9, reproduced pp.127, 160.

2001

Barbara Braun, Pre-Columbian Art in a Post-Colonial World: Ancient American Sources of Modern Art, New York 2001, pp.93–135.

2004

Emma Barker, ‘English Abstraction: Nicholson, Hepworth and Moore in the 1930s’, in Steve Edwards and Paul Wood (eds.), Art of the Avant-Gardes, London 2004, pp.273–304, reproduced p.300.

2006

Alan Powers, ‘Henry Moore’s Recumbent Figure, 1938 at Bentley Wood’, in Patrick Eyres and Fiona Russell (eds.), Sculpture and the Garden, London 2006, pp.121–31.

2007

Jeremy Lewinson, Henry Moore 1898–1986, Cologne 2007, reproduced p.46.

2008

Christa Lichtenstern, Henry Moore: Work – Theory – Impact, London 2008, reproduced pp.97–8.

2010

Chris Stephens (ed.), Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Tate Britain, London 2010, reproduced pp.152–3.

Technique and condition

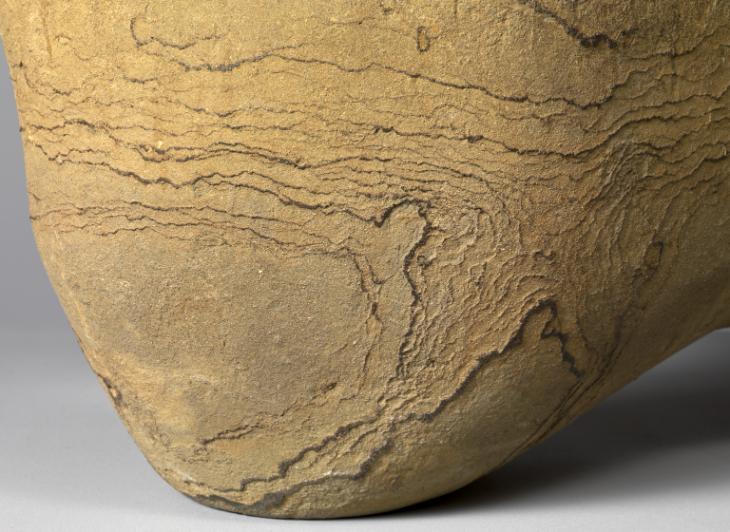

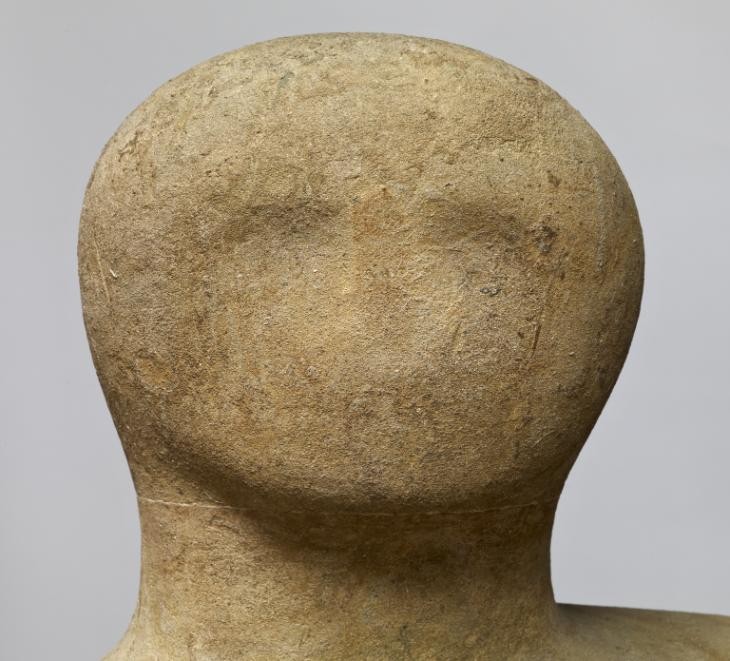

Detail of fossil inclusions in Recumbent Figure 1938

Tate N05387

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.1

Detail of fossil inclusions in Recumbent Figure 1938

Tate N05387

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

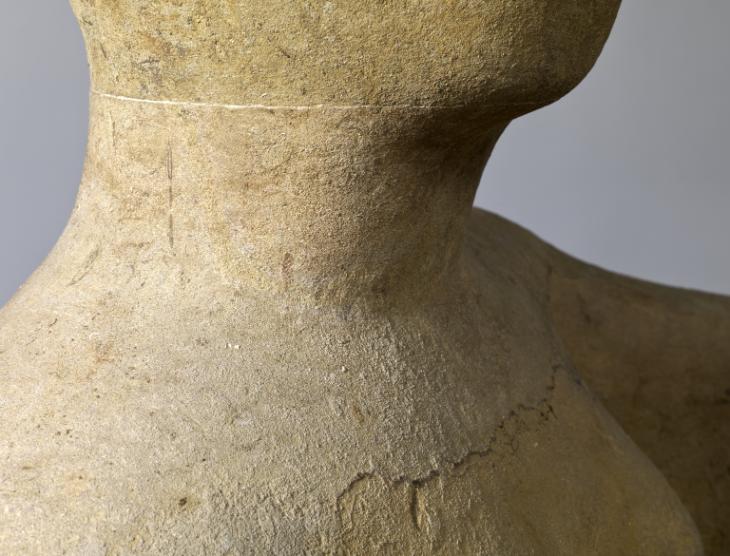

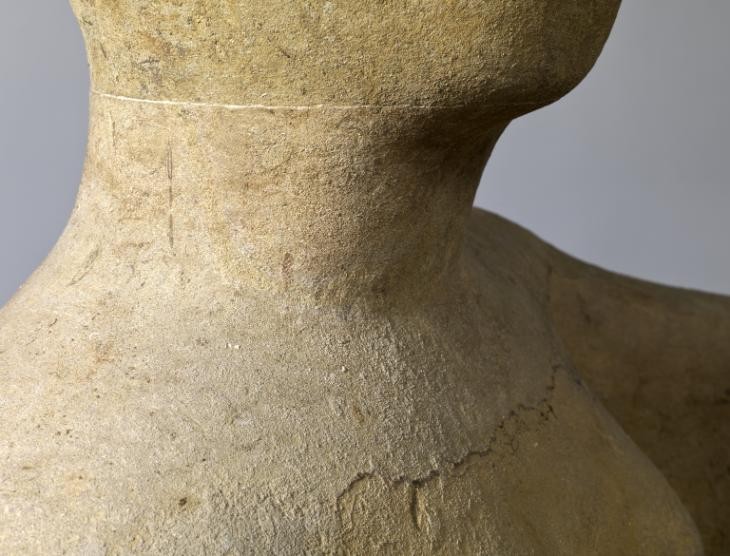

Detail of joining seam through the neck of Recumbent Figure 1938

Tate N05387

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.2

Detail of joining seam through the neck of Recumbent Figure 1938

Tate N05387

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

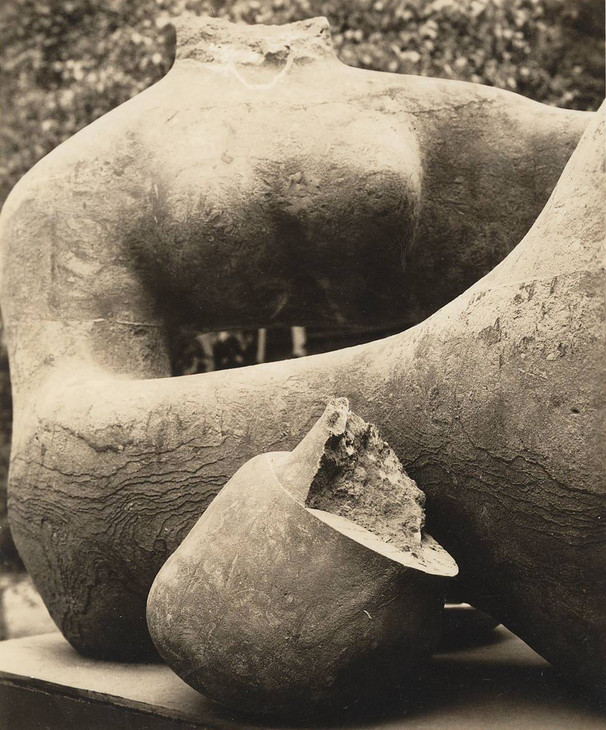

This larger than life size sculpture of a reclining female figure is carved from Hornton stone, a Jurassic limestone quarried in Oxfordshire. It contains a number of fossil inclusions (fig.1) as well as iron minerals that give it characteristic grey-green and brown layers. This stone is usually quarried in relatively small sections so in order to have a piece large enough to carve Recumbent Figure Moore had a composite block made comprising three layers bonded with an adhesive. There are two joins: one runs horizontally through the centre of the body and one through the neck (fig.2). The joins have been matched with the colour of the stone to ensure that they are less visible.

Before carving the sculpture Moore made maquettes of the work which allowed him to experiment with the form and understand how it would be seen from various angles. The sculpture was carved outdoors in Kingston in Kent, probably with the help of Moore’s assistant Bernard Meadows. Investigations with a metal detector have shown that there are dowels through the top part of both arms, through the figure’s left leg and through the neck. These were probably inserted during fabrication to support the more vulnerable areas. The sculpture is unsigned but there is a small stamp in purple ink on the underneath at the centre. It is approximately 15 mm in diameter and consists of the letter ‘P’ over ‘G/37’ surrounded by a circle. A similar stamp is seen on the underside of Moore’s Half Figure 1932 (Tate T00241). It is likely that these stamps were applied after completion but it is not clear at present what they stand for.

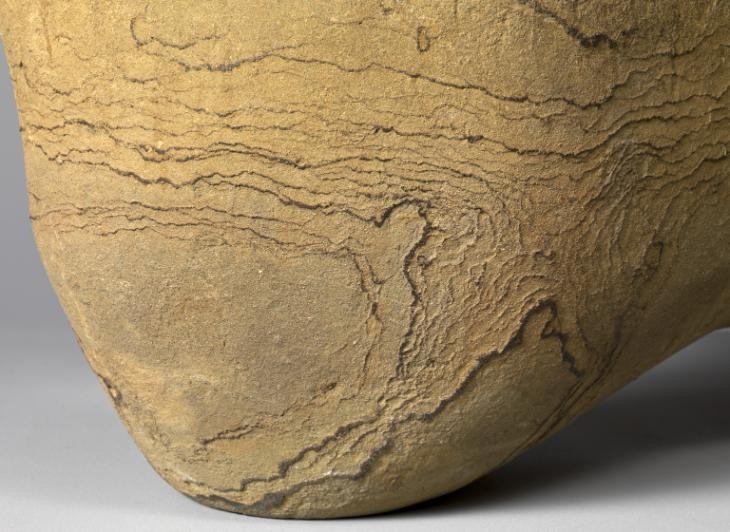

Detail of iron-rich veins in Recumbent Figure 1938

Tate N05387

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.3

Detail of iron-rich veins in Recumbent Figure 1938

Tate N05387

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore

Recumbent Figure 1938 knocked off its plinth at MoMA in June 1944

Tate N05387

© Tate

Fig.4

Henry Moore

Recumbent Figure 1938 knocked off its plinth at MoMA in June 1944

Tate N05387

© Tate

In 1939 the sculpture was loaned to the New York World’s Fair before going on display in the sculpture garden of the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), where it stayed during the Second World War. During this time the sculpture eroded slightly due to exposure to the elements, and the harder, iron-rich veins in the stone now stand proud of the surface (fig.3). In 1944 vandals pushed the sculpture off its plinth, which resulted in serious damage (fig.4). The original fabrication join at the neck came apart and took with it a small section of stone at the front. There was also a loss to the figure’s right knee along with a number of abrasions. The sculpture was repaired at MoMA and losses were initially filled with cement. Later restoration was carried out at the Victoria & Albert Museum, London, in 1977. A detailed investigation of the sculpture and an assessment of its condition was carried out at Tate in 1995.1 This determined the location and composition of previous treatments, and was followed by extensive cleaning and the removal of unsightly repairs. New fills were made using a combination of acrylic emulsions and Hornton stone powder, which was ground to the correct grain size to integrate the repair with the surrounding stone. The original green-grey and brown colours of the limestone are now clearly visible once again.

Lyndsey Morgan

October 2011

Entry

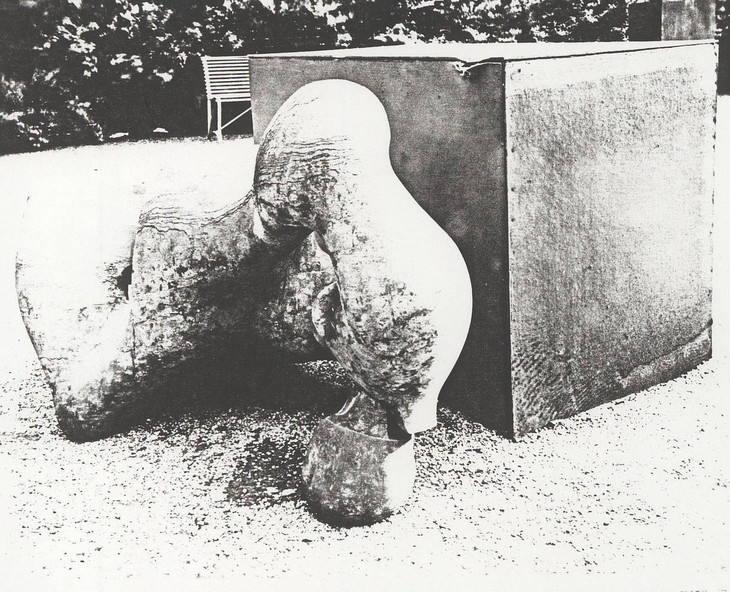

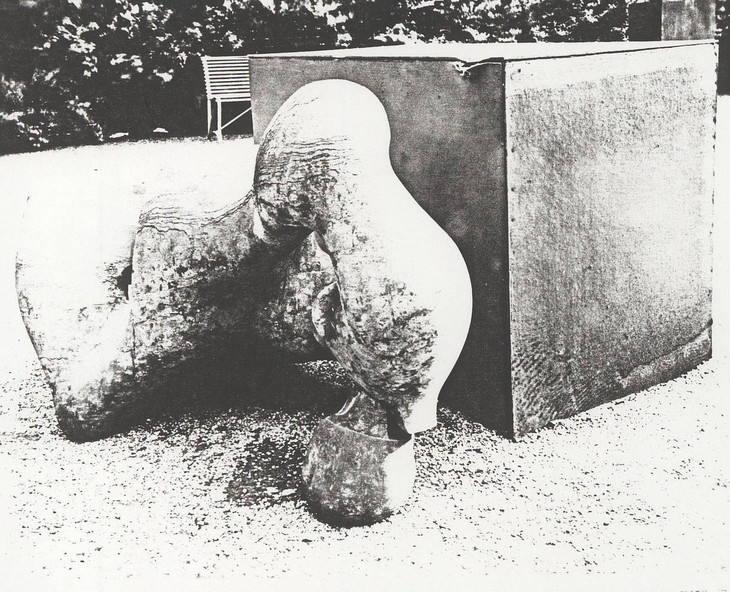

Recumbent Figure 1938 is a large sculpture of a reclining female figure carved from a rectangular block of Green Hornton stone. The sculpture was commissioned by Russian émigré architect Serge Chermayeff (1900–1996) in 1938 for the grounds of Bentley Wood, his house in Halland, Sussex. In 1955 Moore recalled that Chermayeff:

invited me, in 1936, to look at the site and lay-out of a house that he was building for himself in Sussex. He wanted me to say whether I could visualise one of my figures standing at the intersection of terrace and garden. It was a long, low-lying building and there was an open view of the long sinuous lines of the Downs. There seemed no point in opposing all these horizontals, and I thought a tall, vertical figure would have been more a rebuff than a contrast, and might have introduced needless drama. So I carved a reclining figure for him, intending it to be a kind of focal point of all the horizontals, and it was then that I became aware of the necessity of giving outdoor sculpture a far-seeing gaze. My figure looked out across a great sweep of the Downs and her gaze gathered in the horizon. The sculpture had no specific relationship to the architecture. It had its own identity and did not need to be on Chermayeff’s terrace, but it so to speak enjoyed being there, and I think it introduced a humanising element; it became a mediator between modern house and ageless land.1

Viewed from the front, the sculpture is made up of three sections: head, shoulders and arms towards the left; a belly or hip area suggested in the middle; and two legs to the right. The sculpture rests on three points – the elbow, the belly and the feet – the surface areas of which increase progressively. Separating these three points are two arched spaces, so that the sculpture may be understood as an amalgamation of peaks and hollows arranged on a diagonal, moving from elbow to knee.

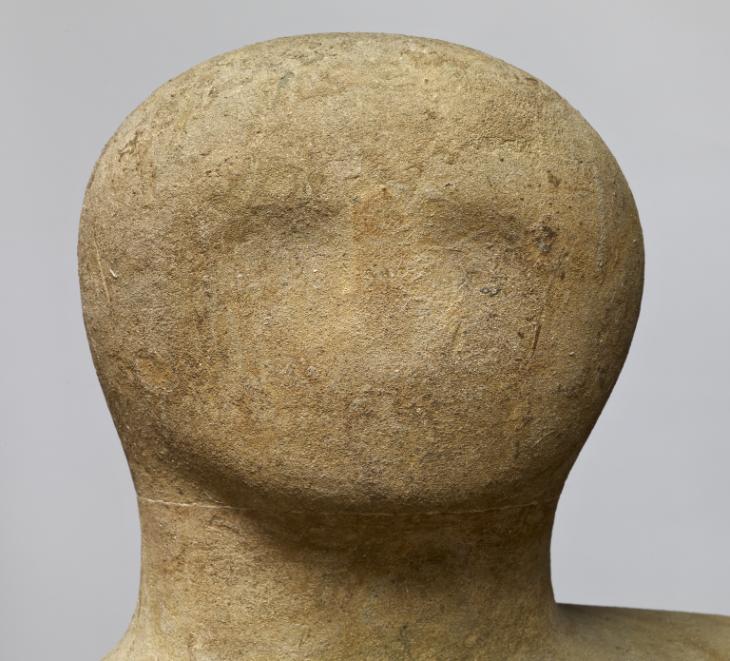

The head, which is the tallest point of the sculpture, is made from an almost spherical block of stone and although the facial area of the head is almost flat, shallow indentations in the stone suggest eyes and a bridge of a nose (fig.1). A chin and jaw-line have also been carved. The back of the head curves inwards, as though the figure has a bun of hair at the back, and leads to a thick neck, which in turn leads down to a pair of broad shoulders and very thick arms. When seen from the rear it is evident that the head and shoulders are dramatically cantilevered over an empty space. The figure’s right arm is positioned at the front of the sculpture; from the large rounded shoulder, the upper arm narrows slightly and projects downwards on a slight diagonal, suddenly expanding into a bulbous elbow on which the sculpture is supported. The arm is bent at the elbow and the forearm extends on an upwards diagonal to merge with the middle section of the sculpture, a large globular area where a belly and hips would be expected. The left arm reaches out horizontally from the left shoulder and arcs around the upper chest, where two projecting breasts are located. The stone has been hollowed out below the bust line and between the two arms so that it is possible to see through the sculpture. From the rear the left arm and shoulder appears as a continuous self-supporting ledge, while the top of the right arm appears to be a flat shelf-like surface which runs parallel to the left arm and shoulder. The empty hollow running through the torso and back of the sculpture contrasts with the bulky mass of the central section.

Like the right arm, the right leg is positioned towards the front of the sculpture. The right thigh extends from the central mass of stone on an upwards diagonal and is bent at the knee so that the calf extends diagonally downwards. The rounded peak of the knee projects upwards and outwards, below which Moore carved out a recessed area to demarcate the edge of the leg. In this concave recess is an oval shaped hole. From the front the left leg and knee are barely visible. However, from the rear the left elbow rests next to the slightly curved left knee, creating a pair of interlocking rounded forms. Underneath the left leg is an arched space distinguishing the thigh and the calf, although this calf is not tubular but is presented as a rectangular block with an almost flat top. Viewed from the foot of the sculpture, the right knee is noticeably taller and broader than the left. The knees are separated by a u-shaped hollow, underneath which Moore carved a shallower recess in the stone.

Henry Moore

Reclining Figure 1929

Brown Hornton stone

Leeds City Art Gallery

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.2

Henry Moore

Reclining Figure 1929

Leeds City Art Gallery

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Detail of fossil inclusions in Recumbent Figure 1938

Tate N05387

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.3

Detail of fossil inclusions in Recumbent Figure 1938

Tate N05387

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Recumbent Figure was carved in Green Hornton stone, an Engligh material named after the town in Oxfordshire where it was originally quarried. Hornton stone is a Jurassic limestone and can range in colour from sage green to warm brown (the different colours of the rock come from different parts of the quarry). Moore also made works in Brown Hornton stone, including Reclining Figure 1929 (fig.2). As a sedimentary stone it is possible to see fossil inclusions as well as iron minerals in the surface of the stone (fig.3). This sedimentary composition means that the stone is relatively soft, which although good for carving, also means that it is prone to crack under pressure. Due to strata size limitations at some quarries it is difficult to extract blocks larger than approximately 200 x 100 x 20 cm.2 To make this large sculpture, three blocks of unusually large Green Hornton stone were bonded together with adhesive and secured with metal dowel rods at the quarry.3 The seam running horizontally through the middle of the sculpture is clearly visible, and Moore would have used it to guide him where to carve out the large hole in the torso so as not to undermine the strength of the composite block of stone. The other seam is visible around the figure’s neck. In the early 1970s Moore recalled that the block of stone cost him about £50.4

During the 1920s and 1930s Moore worked with a number of indigenous English stones, including Hornton stone and Ancaster stone.5 These materials were primarily used to construct buildings near where they were quarried, and were not conventional materials for carving. In 1978 Moore accounted for his use of English stones, stating:

in the early part of my career I made a point of using native materials because I thought that, being English, I should understand our stones. They were cheaper, and I could go round to a stonemason and buy random pieces. I tried to use English stones that hadn’t been used before for sculpture. I discovered many English stones, including Hornton Stone, from visiting the Geological Museum in South Kensington, which was next door to my college.6

According to the art historian Anne Wagner:

Moore’s use of a substance which, when cut, asserts but does not dramatize or aestheticize its surface is part and parcel of the carving credo ... It is not that these local [English] materials are preferred because they are more “flesh-like”. On the contrary the opposite is true. They are chosen for their specially matte and stony surface, in which both time and place are revealed.7

At the time it was made Recumbent Figure was Moore’s largest stone sculpture. It was carved outdoors in the garden of his cottage, Burcroft, in Kingston, Kent, where he and his wife Irina lived from 1935 to 1939. During these years Moore was Head of the Sculpture Department at Chelsea School of Art, where he worked two days a week. He travelled between London and Kent to fulfil his teaching duties but retained his studio and flat in London until 1940. In 1935 he bought Burcroft and spent as much time there as possible. Moore recalled that one of the attractions of Burcroft was that ‘The cottage had five acres of wild meadow’.8 This outside space enabled Moore to create more work on a much larger scale than he had ever attempted before. In addition to Recumbent Figure, another notable large-scale work from this period is the elm Reclining Figure 1939 (Detroit Institute of Art).9 Moore was able to undertake these large-scale works not only because he had more space but because he hired Bernard Meadows as a carving assistant. Meadows was a sculpture student at Norwich School of Art and worked for Moore during his holidays between 1936 and 1940. Meadows and Moore worked together and squaring up blocks of stone so that Moore had regular blocks to work with, as well as undertaking the first roughing out stage of carving, which entailed removing much of the unwanted stone to create the rough shape of the sculpture. Having an extra pair of hands saved Moore considerable amounts of time and meant that he could get twice the amount of work done. As Moore recalled, ‘my assistant and I were able to carve out of doors eight, nine or even ten hours a day. We would get up very early in the mornings and throw buckets of cold water over each other to make sure we were really awake. Some days we used to go down to Dover by car and swim before lunch’.10

Detail of claw marks on Recumbent Figure 1938

Tate N05387

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.4

Detail of claw marks on Recumbent Figure 1938

Tate N05387

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

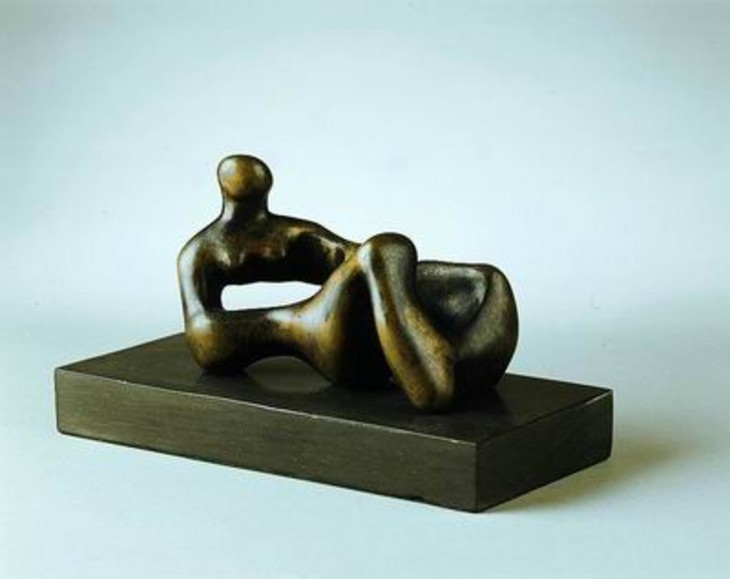

Before carving Recumbent Figure Moore used a clay maquette – a small scale version of the sculpture – as a guide. Art historian Alan Wilkinson has noted that Recumbent Figure ‘appear[s] to have been the first large carving to be preceded by a small maquette’, a practice that would become common in Moore’s work.13 Maquettes are usually made in order to test out an idea or composition in three-dimensional form, and can help an artist decide what may or may not be possible – structurally and aesthetically – on a larger scale. They could also be used as a guide for scaling up three-dimensional ideas. Although Moore had advocated the method of ‘direct carving’ – which involves carving the stone in response to its natural, physical properties rather than shaping it according to a pre-determined plan – he may have felt it necessary, and practical, to create a preliminary maquette for Recumbent Figure to ensure that the stone, and his physical efforts, would not be wasted on such a large sculpture. The maquette also served as a set of instructions for Meadows who was also responsible for carving the stone. Meadows recalled that the clay maquette was scaled up and he followed the arrangement of its forms as accurately as possible in the Green Hornton stone sculpture.14

Henry Moore

Recumbent Figure 1938

Bronze

83 x 127 x 70 mm

The Israel Museum, Jerusalem

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.5

Henry Moore

Recumbent Figure 1938

The Israel Museum, Jerusalem

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

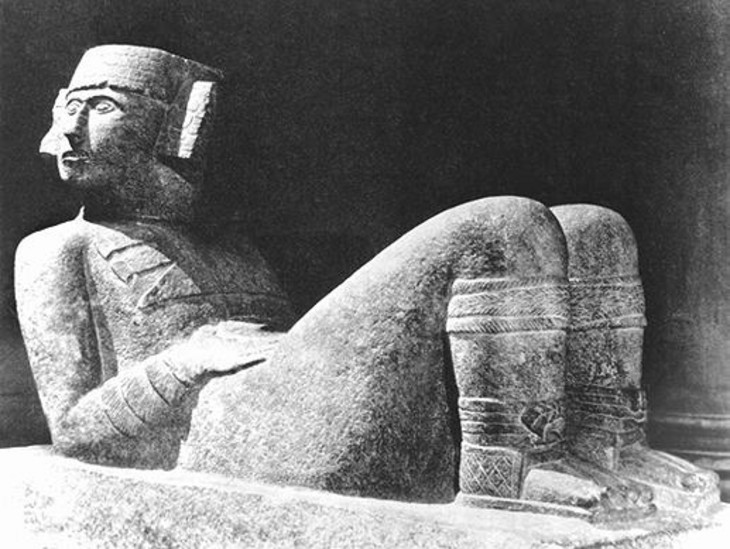

Toltec-Mayan sculpture of Chacmool from Chichén Itzá, c.900–1000

Limestone

1050 x 1480 mm

Museo Nacional de Antroplogia, Mexico City

Fig.6

Toltec-Mayan sculpture of Chacmool from Chichén Itzá, c.900–1000

Museo Nacional de Antroplogia, Mexico City

Michelangelo

Dawn c.1520–34

Medici Chapel, Basilica of San Lorenzo, Florence

Fig.7

Michelangelo

Dawn c.1520–34

Medici Chapel, Basilica of San Lorenzo, Florence

The reclining figure is a subject with a long history in both Western and non-Western art and Moore was familiar with numerous sculptural examples of the subject from Chacmool, a rain spirit of the ancient Toltec-Maya culture (fig.6), to Michelangelo’s carvings of allegorical figures in the Medici Chapel in Florence (fig.7). Moore believed that because the subject was so well known and understood he did not have to represent his reclining figures naturalistically; instead the subject afforded him the opportunity to experiment with ‘formal ideas’:

I want to be quite free of having to find a ‘reason’ for doing the Reclining Figures, and freer still of having to find a ‘meaning’ for them. The vital thing for an artist is to have a subject that allows [him] to try out all kinds of formal ideas – things that he doesn’t yet know about for certain but wants to experiment with, as Cézanne did in this ‘Bathers’ series. In my case the reclining figure provides chances of that sort. The subject-matter is given. It’s settled for you, and you know it and like it, so that within it, within the subject that you’ve done a dozen times before, you are free to invent a completely new form-idea.17

Moore carved his first reclining figure around 1924, but took up the subject with greater seriousness in 1929 and it became his most frequently recurring subject. In 1947 Moore accounted for his preference for the reclining figure, stating:

There are three fundamental poses of the human figure. One is standing, the other is seated, and the third is lying down ... of the three poses, the reclining figure gives most freedom compositionally and spatially. The seated figure has to have something to sit on. You can’t free it from its pedestal. A reclining figure can recline on any surface. It is free and stable at the same time. It fits in with my belief that sculpture should be permanent, should last for eternity. Also, it has repose, it suits me – if you know what I mean.18

Recumbent Figure may be understood as a development of Moore’s earlier Reclining Figure 1929 (fig.2) and Reclining Woman (Mountains) 1930 (fig.8) carved in Brown and Green Hornton stone respectively. Like Recumbent Figure both of these earlier sculptures present a female figure lying down with her belly and legs extending to the right of her upright head and shoulders. In all three sculptures the figure rests on her right elbow, her knees are bent, and she has rounded projecting breasts.

Henry Moore

Reclining Woman (Mountains) 1930

Green Hornton stone

National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.8

Henry Moore

Reclining Woman (Mountains) 1930

National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore

Reclining Figure 1935–6

Elm

Albright-Knox Gallery, Buffalo

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.9

Henry Moore

Reclining Figure 1935–6

Albright-Knox Gallery, Buffalo

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

In Recumbent Figure, however, Moore dispensed with the square, block-like forms of the earlier works and introduced rounded holes and globular shapes. In this way Recumbent Figure is more akin to Moore’s series of reclining figures carved from elm wood which he started in 1935–6 (fig.9). Between 1935 and 1978 Moore carved six such figures in elm. He found that the wood, with its broad grain, was particularly well suited to large-scale carving, and working with larger pieces of wood than he was previously used to freed him from the constraints of size. Working on a large scale, Moore could carve right through the wood, creating holes, or negative spaces, that served to open out the inside of the sculpture and which were as important as its solid forms. These elm sculptures are thus more abstract than Moore’s earlier stone carvings, and Moore recognised that he was taking ‘steps away from realistic representation’ in rendering his figures in this way.19 Reclining Figure 1935–6 and the subsequent Recumbent Figure demonstrate how Moore was stretching the boundaries of his sculptural vocabulary, while simultaneously maintaining a commitment to the figurative form.

Moore’s use of holes in Recumbent Figure represented a major development in his work. Although there has been some debate as to who – Moore or Barbara Hepworth – first incorporated holes as aesthetic components in their sculputure, Moore had drilled and carved through his stone sculptures from as early as 1928.20 However, it was not until the early 1930s that he recognised the aesthetic potential of holes in sculpture. In 1937 Moore articulated his enthusiasm for holes in an article published in the Listener magazine:

Pebbles show nature’s way of working stone. Some of the pebbles I pick up have holes right through them ... A piece of stone can have a hole though it and not be weakened – if the hole is of a studied size, shape and direction. On the principle of the arch, it can remain just as strong. The first hole made through a piece of stone is a revelation. The hole connects one side to another, making it immediately more three-dimensional. A hole can have as much shape-meaning as a solid mass. Sculpture in air is possible, where the stone contains only the hole, which is the intended and considered form.21

As a sculptural element a hole reasserts the three-dimensionality of sculpture. Since his time as a student at the Royal College of Art Moore had been concerned with this three-dimensionality – sculpture existing ‘in the round’ – and in the 1930s found that the incorporation of a hole in and through a sculpture could bring the back of the work to the front. It allows the sculpture to be understood as existing in space, rather than as an object intended to be viewed from a single angle, like a sculptural relief.

In Recumbent Figure it is also possible to see Moore start to broaden out his definition of ‘truth to materials’ and the assertion of the ‘stoniness of the stone’, which had dominated his work in the late 1920s and early 1930s. In works such as Reclining Figure 1929 and Reclining Woman (Mountains) 1930 the shape of the rectangular blocks of stone from which they were carved is evident in the square angles and block-like forms of the sculptures, which appear to weigh the figures down. In comparison, Moore’s use of holes and arches in Recumbent Figure makes the sculpture appear less weighty, belying the true character of Hornton stone. In 1975 Moore reflected on making Recumbent Figure, stating ‘for me this was a bigger freedom in stone than I’d had up to then, not forcing the stone to weakness, keeping still its stony strength and losing the tyranny of the four sided block’.22 For Moore, the curved and cantilevered elements of Recumbent Figure did not suppress the specific material qualities of the stone but extended the notion of ‘truth to materials’ to encompass a truth to natural forms. The weathered asymmetry Moore had identified in nature was recreated in Recumbent Figure, in which no single element had an equivalent. Similarly, Moore exploited the sedimentary lines of iron minerals in the Hornton stone to enhance the sense of organic movement within the sculpture.

The relationship between Moore’s sculpture and the natural landscape has been discussed considerably in art historical literature, but was perhaps first raised by Herbert Read in the introductory essay he wrote for Moore’s first monograph in 1934:

He has gone beneath the flesh to the hard structure of bone; he has studied pebbles and rock formations. Pebbles and rocks show nature’s way of treating stone – smooth sea-worn pebbles reveal the contours inherent in stones, contours determined by variations in the structural cohesion of stone. Stone is not an even mass, and symmetry is foreign to its nature; worn pebbles show the principles of its asymmetric stricture. Rocks show stone torn and hacked by cataclysmic forces, eroded and polished by wind and rain. They show the jagged rhythms into which a laminated structure breaks; the outlines of hills and mountains are the nervous calligraphy of nature. More significant still are the forms built up out of hard materials, the actual growth in nature of crystals, shells and bones ... Bones combine great structural strength with extreme lightness; the result is a natural tenseness of form. In their joints they exhibit the perfect transition of rigid structures from one variety of direction to another. They show the ideal torsions which a rigid structure undergoes in such transitional movements.23

In 1936 the art critic Geoffrey Grigson discussed Moore’s rounded sculptures that recalled the natural world in his essay ‘A Comment on England’, published in the first edition of the magazine Axis. In his essay, Grigson characterised Moore as follows:

MOORE: Product of the multiform inventive artist, abstraction-surrealism nearly in control; of a constructor of images between the conscious and the unconscious and between what we perceive and what we project emotionally into the objects of our world; of the one English sculptor at large, imaginative power, of which is almost master; the biomorphist producing viable work, with all the technique he requires.24

In this statement Moore is described as an artist able to conjure forms from the imagination that still make reference to the real world, resulting in strangely familiar sculptures that give rise to emotional responses. What is noteworthy, however, is Grigson’s use of the term ‘biomophist’ to describe Moore’s use of natural or organic forms and shapes. The art historian Jennifer Mundy has explained that ‘for Grigson “biomorphic” denoted an organic quality that was an indelible residue of the way in which the [sculptural] form had been arrived at’. 25 While ‘biomorphic’ may refer to actual organic shapes or memories of naturally-occurring forms, the term ‘did not necessarily imply that the form looked like anything real’.26 Recumbent Figure may not look like a real reclining female human but it nonetheless resembles a figure in that it is an imaginative simplification of the human body.

Grigson’s understanding of biomorphism encompassed not just artworks that were suggestive of natural forms, but also ideas of biological and primitive origins and beginnings. As such, Recumbent Figure may be said to echo the ancient Mexican Chacmool, as well as recall the viscous, shapeless amoebic forms known from contemporary microscopic biological research.27 This characterisation of Moore’s work as a growing biological life force was made explicit in George Wingfield Digby’s 1955 analysis of Moore’s work.28 Wingfield Digby suggested that:

the chief characteristic of Henry Moore’s art is as regressive urge ... has gone back in search of the tap-root of human life. It has, as it were, regressed to a point far back in the history of human development. There it is in contact with the deep springs of animal life and rejoices once more in the surge of proto-human energy.29

While Wingfield Digby’s interpretation of Moore’s work is perhaps idiosyncratic, it nonetheless echoes the proposition found in the writings of Read and Grigson that Moore’s appreciation of natural forms and his abstraction or simplification of the human figure results in a universally recognisable artistic vocabulary that conveys ‘what is spiritually necessary and eternal’.30

In his 1965 essay on Recumbent Figure the critic David Thompson suggested that rather than simply convey an appreciation of nature, Moore’s sculpture actively utilised motifs found in nature. He stated:

If you stand at the foot of Moore’s ‘Recumbent Figure’ [fig.10], you see a marvellous section between the knees which is like a straight transcript of one of those sea-worn basins in which rock-pools gather. If one found it on the beach, one would stop to admire its perfection of form: the rhythmic spiral in which the lip of the basin broadens out into a hollow cup beneath and at the same time burrows through the rock to the left to fall away into a sort of sea-cave on the other side. Holes, hollows, caverns, basins – in nature these provide a repertory of forms in which we all tend to take delight ... it is obvious that Moore shares this delight and as a sculptor exploits it by re-creating the shapes and configurations in nature which excite it.31

Thompson argued that because the forms found in Recumbent Figure originated in the natural world, Moore’s sculpture cannot be regarded as ‘abstract’. He proposed that if the sculpture were examined in terms of its forms, rather than its ostensible subject – a reclining woman – then its inherent meaning would be immediately discernable: ‘one can see that it is about landscape, about the action of natural forces upon rock; one can understand the frame of reference and can appreciate, in a perfectly straightforward way, the kind of beauty in natural phenomena which Moore is depicting’.32 Thompson concluded that ‘I think it could be claimed that Moore is the first sculptor in history to have found a way of expressing his feelings about landscape. Formerly only painters could describe mountains and cliffs and sea-caves’.33 Remnants of fossilised shells and pebbles serve to reinforce the idea that the sculpture is part of a cycle of natural energy, and may explain why the critic Peter Fuller described Recumbent Figure as an image of ‘Earth Mother’.34

An alternative, art historical explanation for Moore’s turn to organic and curvilinear shapes suggests that works such as Recumbent Figure may have been made in response to the trend for elastic, gelatinous forms already prevalent in Europe and associated in particular with the work of Pablo Picasso. Moore was certainly aware of artistic developments taking place on the continent; his first trip to Paris in 1922 had been followed by regular trips to the city throughout the decade and these visits were supplemented by his study of French art periodicals including Cahiers d’Art (from 1926) and the surrealist periodical Documents (1929–30). Both these journals championed the work of Picasso as the major force in contemporary art and in 1930 Moore bought the third issue of Documents, a special edition dedicated to Picasso’s work. In this publication Moore saw reproductions of Picasso’s drawings and paintings made in Cannes in c.1927–9 of monumental nude women standing on a beach with large, block-like limbs and globular breasts. According to art historian Christopher Green, Moore’s creation of figurative, albeit non-naturalistic sculpture can be explained through Picasso’s fragmented, gelatinous figures reproduced in Cahiers d’Art and Documents. For Green, Moore’s affinity with Picasso was rooted in ‘their knowledge of the human body, however far they moved from straight representation’.35

Jean Arp (Hans Arp)

Sculpture to Be Lost in the Forest 1932, cast c.1953–8

Tate T04854

© DACS, 2014

Fig.11

Jean Arp (Hans Arp)

Sculpture to Be Lost in the Forest 1932, cast c.1953–8

Tate T04854

© DACS, 2014

rounded forms convey an idea of fruitfulness, maturity, probably because of the earth, woman’s breasts, and most fruits are rounded, and these shapes are important because they have this background in our habits of perception. I think the humanist organic element will always be for me of fundamental importance in sculpture, giving sculpture its vitality ... My sculpture is becoming less representational, less an outward visual copy, and so what people would call more abstract; but only because I believe that in this way I can present the human psychological content of my work with the greatest directness and intensity.40

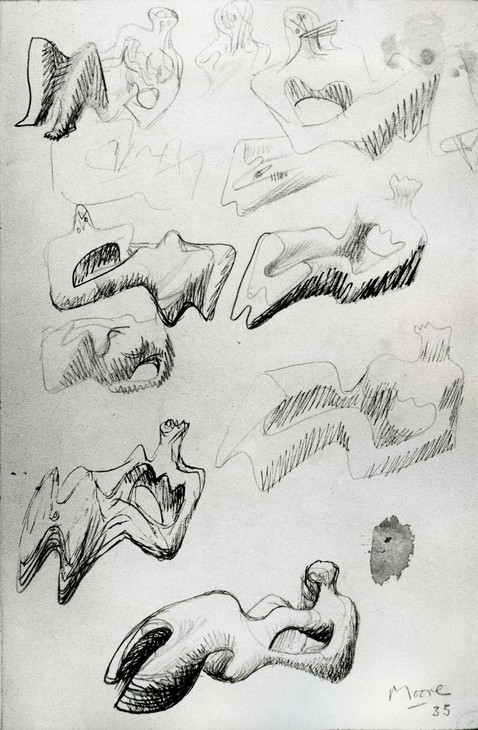

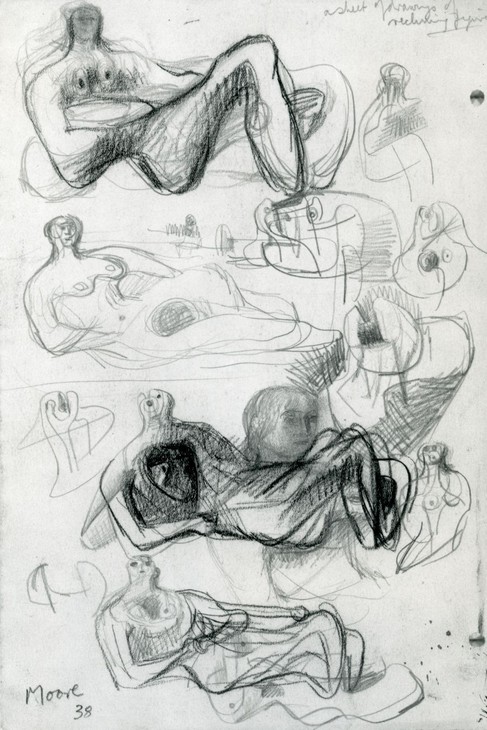

The reclining figure was a subject that Moore also returned to throughout the 1930s in his drawings. Although it is often difficult to link Moore’s preparatory drawings to specific sculptures, in Reclining Figures 1935 (fig.12) Moore drew a series of abstracted reclining figures that closely resemble Recumbent Figure. In contrast to the more natuaralistic figure in the top left of the page – the legs of which seem to be conjoined by fabric stretching between the two calves – the drawings below present the two legs as protrusions from the same structural form. The curved hollows and arches seen in these drawings also point to how Moore would lift the weight of the sculpture off the ground in Recumbent Figure.

Henry Moore

Reclining Figures 1935

Graphite, pen and ink on paper

273 x 181 mm

Private collection

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.12

Henry Moore

Reclining Figures 1935

Private collection

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Henry Moore

Ideas for Sculpture: Reclining Figures 1938

Graphite and crayon on paper

275 x 190 mm

Private collection

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.13

Henry Moore

Ideas for Sculpture: Reclining Figures 1938

Private collection

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

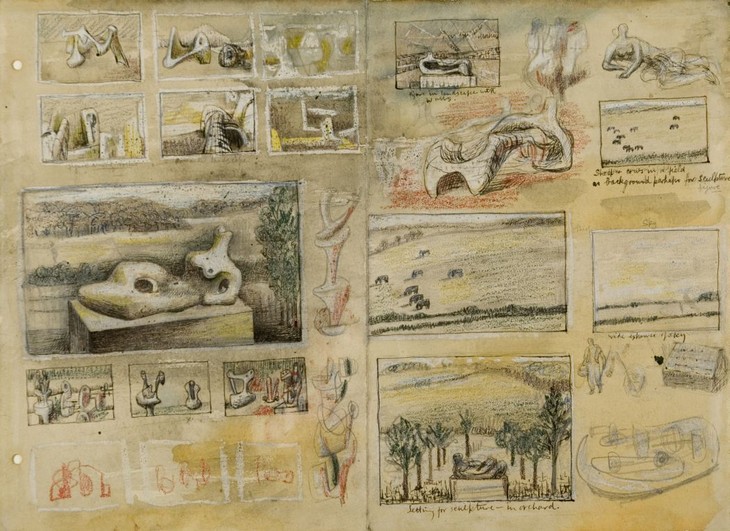

In the 1977 exhibition of Moore’s drawings held at the Tate Gallery, the curator Alan Wilkinson labelled the drawing now called Ideas for Sculpture: Reclining Figures 1938 (fig.13) with the title Ideas for Sculpture: Study for Tate Recumbent Figure.41 Wilkinson identified the sketch in the top left corner of the page as the definitive study for Recumbent Figure. The drawing does bear a striking resemblance to the sculpture, although here the diagonal from the right elbow to the knee is much more pronounced, as are the two arches underneath the body. However, while the left leg appears to be more prominent than that of the finished sculpture, the drawing nonetheless contains the basic design of Recumbent Figure. Wilkinson suggested that it was from this drawing that Moore created the clay maquette which he used as a reference when carving Recumbent Figure.42

The Chermayeff commission was the first time that Moore made a free-standing sculpture in relation to an architectural structure. In an interview held in the early 1970s, Moore was keen to stress that Recumbent Figure was made as a site-specific comission, stating, ‘Chermayeff was building himself a new house and wanted me to come and see it. During our visit he asked whether I might do a sculpture that he could put there. Not exactly a commission for a certain design – I have never done that – but he liked some of the stone pieces I was then doing’.43 However Moore also noted that the sculpture did not ‘need to be on Chermayeff’s terrace’, that it was not bound to a specific place. Although Moore later claimed that ‘the sculpture had no specific relationship to the architecture’, it was nonetheless positioned to contrast with the design of the house. As the architectural historian Alan Powers has described:

The sculpture would normally be discovered by a visitor stepping out from the house to view the landscape who would find that the landscape was already being viewed by another presence, for the Recumbent Figure was deliberately positioned to look away from the house. Taking a walk ... the viewer could then turn back and look at its relationship to the architecture.44

Moore’s awareness of the sculpture’s relationship to the horizon, and his subsequent assertions that his sculptures are best seen in natural landscapes has meant that interpretations of Recumbent Figure have often focused on its placement at Bentley Wood. For example, the art historian Christa Lichtenstern has suggested that Recumbent Figure is an ‘exceptionally vivid’ example of how Moore was able to make the landscape and figure enhance one another.45 She suggested that ‘in making the figure assimilate the undulating hills in the way that a magnifying glass collects the sun’s rays, the artist not only responded to the rhythmic call of the landscape, but also provided an internal focus for the sculpture itself’.46 In regard to its position on Chermayeff’s terrace, Lichtenstern suggested that Moore harnessed ‘the exchange of three-dimensional energies between landscape and figure’.47 If, as Read, Grigson and others implied, Recumbent Figure exists at the intersection between the human form and the natural world, its position on the terrace at Bentley Wood only served to amplify such interpretations. As Moore himself noted, the sculpture acted as a ‘mediator between modern house and ageless land’.

Looking back at his time in Kent, Moore identified that it was during this period of his career that his interest in the relationship between sculpture and the natural environment became a major preoccupation:

Living at Burcroft was what probably clinched my interest in trying to make sculpture and nature enhance each other. I feel that the sky and nature are the best setting for my sculpture. They are asymmetrical, unlike an architectural background with its verticals and horizontals. In a natural setting, the background to a sculpture changes if you move only a very small distance.48

Henry Moore

Ideas for Sculpture in Landscape c.1938

Graphite, wax crayon, watercolour, pen and ink on paper

277 x 381 mm

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Michael Phipps, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.14

Henry Moore

Ideas for Sculpture in Landscape c.1938

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Michael Phipps, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Recumbent Figure did not stay at Bentley Wood for long; Powers suggests probably only twelve months.49 In the early part of 1939 Chermayeff was declared bankrupt and although he had agreed a purchase price of £300 with Moore for Recumbent Figure, he only paid a £50 deposit. Sometime between 18 January and 26 March Chermayeff suggested that the work be returned to Moore, to sell to another client.50 Moore refunded the deposit and the sculpture was returned to his studio. A few months later Bentley Wood was sold and in 1940 Chermayeff and his family emigrated to the United States.

Shortly after the sculpture was returned to Moore, the art historian and writer Kenneth Clark advised Moore to offer it to the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York. Moore first met Clark in 1929 or 1930 and by the late 1930s the two men were close friends and Moore regularly turned to Clark for advice. Clark was the Director of the National Gallery from 1934 to 1945 and in this elevated position within the art establishment was able to help and influence artists and collectors. Clark was a generous collector and supporter of many artists as well as a promoter of those artists he most favoured.

On Clark’s suggestion, Moore proposed the acquisition of Recumbent Figure to MoMA, but the gallery was not in a position to purchase it. Clark then recommended that Moore offer to sell it to the Contemporary Art Society (CAS), which was, and remains, an organisation dedicated to raising funds for the purchase of contemporary works of art for British national public collections. In the late 1930s Clark was the official buyer for the CAS and in a letter to Clark written on 8 April 1939, Moore said:

I’ve been wondering since I wrote to you about the price of the large reclining figure, whether you might think I have put too high a price on it, that I’ve been greedy about it. And I should hate to believe you were thinking anything like that.

I’ve so much else to thank you for, the great help for example you gave in so many ways towards making my recent drawing show a success, & I owe so much to your friendliness during the last year or two, that of course I’m ready to meet your ideas about it all, so should be glad if you’d write and tell me what you think the price should be from your point of view as buyer for The Contemporary Art Society. Perhaps you had thought it would be about half its exhibition figure, i.e. £250.51

Despite Moore’s concerns, the price was set at £300, the sale of Recumbent Figure was agreed, and in April 1939 the CAS presented the sculpture to the Tate Gallery. Tate’s acceptance of Recumbent Figure represented a change in the reception of Moore’s work by the Tate and the British art establishment at large. The acquisition was made possible by the recent appointment of John Rothenstein as Director of the Tate; his predecessor J.B. Manson had refused to acquire any of Moore works, having told Tate Trustee Robert Sainsbury, ‘Over my dead body will Henry Moore ever enter the Tate’.52

Immediately following its presentation to the gallery Recumbent Figure was lent to the British Pavilion at the New York World’s Fair in the summer of 1939. Chermayeff had agreed to loan the work to the British Council, which was selecting artworks for the British Pavilion under the guidance of Kenneth Clark, in January 1939, and the Tate honoured this commitment.53

The Fair was due to close in October 1939, but with the outbreak of the Second World War that September the British Council found that they were unable to bring the artworks on display in New York back the UK. In November it was suggested that the paintings and drawings be sent on a tour of Canada ‘until Europe is in a more settled condition’, while the sculptures, which included works by Eric Gill and Eric Kennington as well as Moore, eventually found a home at MoMA.54 In September 1940 Rothenstein wrote to MoMA’s director Alfred H. Barr thanking him for storing the works:

I am informed by our Department of Overseas Trade that you have told [George] Baldock of the British Pavilion, New York World’s Fair, that you will be so kind as to store the sculpture of Gill, Henry Moore, and Kennington for the duration of the war, at the museum. I need not tell you that the Trustees of this Gallery are most grateful for your kindness and help at this difficult moment.

The trustees were in any event disinclined to expose the sculptures to the risk of loss or damage by returning them to London. Now, serious bomb damage at the Tate makes it impossible to receive them here.55

The durability of Recumbent Figure was severely tested during the six years that it spent at MoMA. Rothenstein and the Tate trustees agreed that the sculpture could be exhibited outside in MoMA’s sculpture garden. Although Moore himself raised no objections, Rothenstein stipulated that the sculpture should be brought indoors during the ‘coldest winter months’.56 Barr responded to this request, stating: ‘I do think you are being a bit over cautious ... We have consulted Chermayeff. He says that the Moore was out-doors [sic] during a very hard winter and suffered no damage. He is perfectly happy to see it remain outdoors’.57 Although the sculpture was placed inside on the gallery’s sixth floor during the winters, it nonetheless suffered some damage due to New York’s extreme temperatures; the surface lost its smooth finish, accentuating the three distinct layers of the Hornton stone, and the iron rich veins became prominent. In 1955, Moore recalled:

it had a pretty tough experience when it was a war-time refugee in New York ... When it came back it was in a very weather-worn condition, owing to the extremes of heat and cold in New York, and its proximity to the sea. But at least I discovered that Hornton – a warm, friendly stone that I like using – is not suitable for exposure in intemperate climates.58

It is significant that Barr had been in touch with Chermayeff regarding the placement of Recumbent Figure outside. In December 1941 Barr wrote to Rothenstein intimating that he believed that Chermayeff was still the owner of the sculpture and, if this were the case, that MoMA would like to acquire it. Barr explained that he was contacting Rothenstein to enquire whether Tate was also ‘interested in the piece’.59 Given that Recumbent Figure had been in the Tate’s collection since 1939, Rothenstein was confused by Barr’s interest in acquiring the sculpture and appealed to Moore for clarification. Moore explained to Rothenstein that Chermayeff had recently sent him a letter proposing that MoMA acquire the work:

You recall that when Bentley disintegrated ... + all, You suggested that the Tate might want your old girl + I agreed to let this go ahead – She has since then been in the British Pavilion + later at the Museum of Modern Art – Since I have never heard from you that she has definitely changed masters + since she appears labeled with my ownership here – and since for then the Museum of MA wrote me asking if I would sell her I have assumed that her marriage to the Tate has never been consumated [sic]’.60

Thankfully, Moore was able to write to Chermayeff to clarify the situation regarding ownership of the work, and Barr dropped the matter with Rothenstein.61

Henry Moore

Recumbent Figure 1938 knocked off its plinth at MoMA in June 1944

Tate N05387

© Tate

Fig.15

Henry Moore

Recumbent Figure 1938 knocked off its plinth at MoMA in June 1944

Tate N05387

© Tate

Photograph showing the break at the neck of Recumbent Figure 1938, in June 1944

Tate N05387

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.16

Photograph showing the break at the neck of Recumbent Figure 1938, in June 1944

Tate N05387

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

The New York climate was not the only cause of damage to Moore’s sculpture while it was on display at MoMA. In June 1944 two vandals broke into the sculpture garden in the middle of the night and knocked Recumbent Figure off its plinth (fig.15). The figure’s head cracked and broke at the base of the neck (fig.16). In his letter to Rothenstein informing him of the damage, Barr downplayed the incident, stating ‘Fortunately the damage to the sculpture was less than might have been expected. The only serious damage was that the head was knocked off, as you will see from the enclosed photographs’.62

Following the fall, the sculpture was immediately repaired with a bronze dowel and cement and moved into an indoor gallery for display until it was safely returned to the Tate in March 1946. Barr and Rothenstein jointly agreed that MoMA’s insurance company would pay $600 in compensation to Tate for the damages to the sculpture. On the return of Recumbent Figure to Tate, Barr’s successor John James Sweeney wrote to Rothenstein on 7 March 1946 saying ‘it was with great regret that we saw it leave. It had won wide esteem among the Museum visitors’.63

Despite being weather-worn in New York, Recumbent Figure was displayed outside in the first open-air exhibition at Battersea Park, which opened in May 1948. Organised by the London County Council the exhibition included works by a group of leading twentieth-century sculptors, including Auguste Rodin, Aristide Maillol and Ossip Zadkine, in what art historian Margaret Garlake has described as ‘an unprecedented format that allowed people to explore works of art at leisure in a relaxed atmosphere very different from the intimidating formality of the gallery’.64

The open-air exhibition at Battersea Park brought Moore’s work to the attention of the general public and the reception of his work was on the whole immensely positive. However, Recumbent Figure did feature in a political caricature by Sid Scales published in the Recorder on 7 August 1948, in which the Labour Prime Minister Clement Attlee is presented carving out his new vision of Britain, while the nation suffers from a variety of ailments including rationing, brain-washing ideology and nationalisation, variously represented by different types of modern sculpture. Recumbent Figure is presented with sad, downturned eyes, with a cup and saucer balencing precariously on its upraised knee. Moore had been photographed with Aneurin Bevan, Foreign Secretary in Attlee’s cabinet, at the opening of the open-air exhibition, and modern sculpture such as Moore’s became an early target for those seeking to challenge Atlee’s vision of a new society in the post-war era.

Moore’s sculpture was not just used in political satire. In 1965 the critic David Thompson noted that:

if a cartoonist wants to make fun of modern art and draw an immediately recognisable symbol of it, the liklihood is that he will, for a paining depict a face with both eyes on the same side of the nose, or for a sculpture show a bulbous potatoe-shape with a hole through it. In other words, he will make an explicit reference, in painting to Picasso, and in sculpture to Henry Moore.65

Thompson suggested that this type of parody was in fact a ‘back-handed compliment’, since cartoons identified Moore, and his characteristic use of holes as exemplars of modern art.66

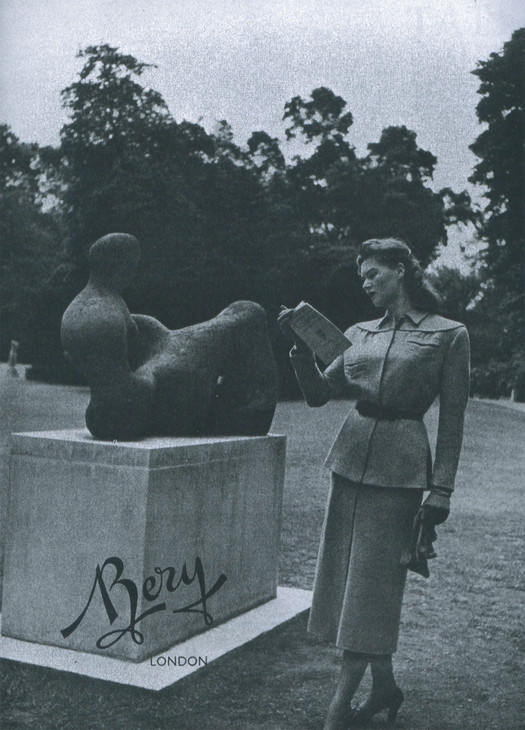

By contrast, in September 1948 Recumbent Figure was pictured in an advertisement for the fashion retailer Bery in the pages of Vogue magazine (fig.17). A smartly dressed woman is pictured reading the catalogue for the open-air sculpture exhibition standing adjacent to Recumbent Figure. In this context Moore’s sculpture may be regarded as a symbol of forward thinking modernity, the type of art appreciated by fashion-concious modern women.

Through its public exposure in caricature, advertsisments and exhibitions, Recumbent Figure became not only one of Moore’s most recognised artworks, but also one of the most well known works in Tate’s collection. This was perhaps underlined by the inclusion of Recumbent Figure in a tiled mural in Pimlico Underground station, near to the Tate Gallery, in 1972.

In 1972 Recumbent Figure was included in the groundbreaking exhibition Sculpture for the Blind, in which twelve sculptures from Tate’s permanent collection were exhibited for the blind and partially sighted, who were encouraged to experience the works through touch. The exhibition was supplemented by loans from Moore’s personal collection. In a review of the exhibition critic Harold Osborne determined that ‘the Tate Gallery has shown commendable imagination and initiative in staging this exhibition’,67 and letters held in The Henry Moore Foundation Archive reveal that blind audiences appreciated the opportunity to experience Moore’s sculptures through touch.68 In December 1976, a C. Simms of Ilford, Essex, wrote to thank Terry Measham, Assistant Keeper at the Tate, for curating the exhibition. Simms wrote:

I had no idea of the pleasure and sense of satisfaction I would gain from abstract works ... the proportions and pure mass of Henry Moore’s ‘Recumbent Figure’ was at the very least surprising and on detailed examination, I think a work which could be looked at from a tactile point of view over and over again.69

Installation view of The Henry Moore Gift, Tate Gallery 1978, showing Recumbent Figure 1938

Tate Archive

Fig.18

Installation view of The Henry Moore Gift, Tate Gallery 1978, showing Recumbent Figure 1938

Tate Archive

Alice Correia

January 2013

Notes

Henry Moore in Sculpture in the Open Air, British Council film, 1955, transcript reprinted in Alan Wilkinson (ed.), Henry Moore: Writings and Conversations, Aldershot 2002, p.258–9.

See Alice Correia, ‘Henry Moore, Girl 1931 Tate N06078’, catalogue entry, http://www.tate.org.uk/art/research-publications/henry-moore/henry-moore-om-ch-girl-r1172005 , accessed 11 September 2015.

Anne Middleton Wagner, Mother Stone: The Vitality of Modern British Sculpture, New Haven 2005, p.22.

For an image of Moore’s elm Reclining Figure 1939 see http://www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-britain/exhibition/henry-moore-0/henry-moore-room-guide/henry-moore-room-7 , accessed January 2013.

Henry Moore cited in Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Arts Centre, Folkestone 1983, reprinted in Wilkinson 2002, pp.58–9.

Henry Moore cited in J.D. Morse, ‘Henry Moore Comes to America’, Magazine of Art, vol.40, no.3, March 1947, pp.97–101, reprinted in Philip James (ed.), Henry Moore on Sculpture, London 1966, p.264.

Henry Moore cited in Arnold Haskell, ‘On Carving’, New English Weekly, 5 May 1932, pp.65–6, reprinted in Wilkinson 2002, p.190.

See Matthew Gale, ‘Seated Figure 1932–3 by Barbara Hepworth’, catalogue entry, April 1997, https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/hepworth-seated-figure-t03130/text-catalogue-entry , accessed 21 January 2014.

Henry Moore, ‘A Sculptor Speaks’, Listener, 18 August 1937, pp.338–40, reprinted in Wilkinson 2002, p.195.

Henry Moore cited in Philip James, ‘Henry Moore Looking at His Work, with Philip James’, audio recording, 1975, transcript reprinted in Wilkinson 2002, p.259.

Jennifer Mundy, ‘Comment on England’ in Chris Stephens (ed.), Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Tate Britain, London, 2010, p.28.

George Wingfield Digby, Meaning and Symbol in Three Modern Artists: Edvard Munch, Henry Moore, Paul Nash, London 1955, pp.70–1.

Peter Fuller, ‘Henry Moore: An English Romantic’ in Susan Compton (ed.), Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Royal Academy of Arts, London 1988, p.41.

Christopher Green, ‘Henry Moore and Picasso’ in James Beechy and Chris Stephens (eds.), Picasso and Modern British Art, exhibition catalogue, Tate Britain, London 2012, p.131.

John Russell, Henry Moore, 1968, 2nd edn, London 1973, p.74; Michel Remy, Surrealism in Britain, Aldershot 1999, p.70. Although Remy does not provide evidence as to when or where Moore and Arp met, it is his contention that they did meet.

Alan Powers, ‘Henry Moore’s Recumbent Figure, 1938 at Bentley Wood’, inPatrick Eyres and Fiona Russell (eds.), Sculpture and the Garden, London 2006, p.125.

Chairman of the Fine Arts Committee, British Council, letter to Acting Director, Tate Gallery, 2 November 1939, Tate Public Records TG/4/9/568/1.

See Henry Moore, letter to Serge Chermayeff, 19 December 1941, copy sent by Moore to John Rothenstein, 26 December 1941, Tate Archive TGA 8726/3/11.

Margaret Garlake, New Art / New World: British Art in Postwar Society, New Haven and London 1998, p.212.

Related catalogue entries

How to cite

Alice Correia, ‘Recumbent Figure 1938 by Henry Moore OM, CH’, catalogue entry, January 2013, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015, https://www