Henry Moore OM, CH Three Part Object 1960

Image 1 of 11

-

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Part Object 1960© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Part Object 1960© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Part Object 1960© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Part Object 1960© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Part Object 1960© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Part Object 1960© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Part Object 1960© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Part Object 1960© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Part Object 1960© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Part Object 1960© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Part Object 1960© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Part Object 1960© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Part Object 1960© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Part Object 1960© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Part Object 1960© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Part Object 1960© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Part Object 1960© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Part Object 1960© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Part Object 1960© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Part Object 1960© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Part Object 1960© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Three Part Object 1960© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH,

Three Part Object

1960

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Three Part Object 1960 has been considered in relation to Moore’s interest in animal forms and his ambition to convey the ‘vitality’ of living creatures. This concern with the essential characteristics of natural, organic materials connects this work to Moore’s earlier biomorphic sculptures of the 1930s and to the work of Jean Arp.

Henry Moore OM, CH 1898–1986

Three Part Object

1960

Bronze

1264 x 718 x 613 mm

Inscribed ‘Moore 8/9’ and stamped with foundry mark ‘H. NOACK BERLIN’ on base

Presented by the artist 1978

Number 8 in an edition of 9 plus 1 artist’s copy

T02285

Three Part Object

1960

Bronze

1264 x 718 x 613 mm

Inscribed ‘Moore 8/9’ and stamped with foundry mark ‘H. NOACK BERLIN’ on base

Presented by the artist 1978

Number 8 in an edition of 9 plus 1 artist’s copy

T02285

Ownership history

Presented by the artist to Tate in 1978 as part of the Henry Moore Gift.

Exhibition history

1960–1

Henry Moore: An Exhibition of Sculpture from 1950–1960, Whitechapel Art Gallery, London, November 1960–December 1961, no.67.

1962

Henry Moore: An Exhibition of Sculpture and Drawings, Arts Council touring exhibition: Arts Council Gallery, Cambridge, February–March 1962; York City Art Gallery, York, March–April 1962; Castle Museum, Nottingham, April–May 1962; Southampton Art Gallery, Southampton, May–June 1962, no.46.

1963

Henry Moore: An Exhibition of Sculpture and Drawings, Ferens Art Gallery, Kingston upon Hull, October–November 1963, no.36.

1966

Henry Moore: Sculpture and Drawings, New Metropole Arts Centre, Folkestone, April–May 1966; City Art Gallery, Plymouth, June–July 1966, no.41.

1968

Henry Moore, Rijksmuseum Kröller-Müller, Otterlo, May–July 1968; Museum Boymans-Van Beuningen, Rotterdam, September–November 1968, no.106.

1968

Henry Moore, Tate Gallery, London, July–September 1968, no.113.

1969

Henry Moore, Heslington Hall, York, March 1969, no.25.

1969

Henry Moore: Drawings and Sculpture, Gordon Maynard Gallery, Welwyn Garden City, July 1969, no.4.

1969

Henry Moore Exhibition in Japan, 1969, National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo, August–October 1969, no.46.

1971

Henry Moore: Sculpture, Drawings, Graphics, Turnpike Gallery, Leigh, November–December 1971, no.8.

1972

Henry Moore, Playhouse Gallery, Harlow, March–April 1972, no.2.

1972

Mostra di Henry Moore, Forte di Belvedere, Florence, May–September 1972, no.112.

1978

The Henry Moore Gift, Tate Gallery, London, June–August 1978, no number.

References

1960

Henry Moore: An Exhibition of Sculpture from 1950–1960, exhibition catalogue, Whitechapel Art Gallery, London 1960, reproduced no.67.

1962

Henry Moore: An Exhibition of Sculpture and Drawings, exhibition catalogue, Arts Council Gallery, Cambridge 1962, reproduced pl.1.

1962

Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, M. Knoedler and Co., New York 1962 (another cast reproduced).

1965

Herbert Read, Henry Moore: A Study of his Life and Work, London 1965, p.240 (?another cast reproduced pl.231).

1965

Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Marlborough Gallery, Rome 1965 (another cast reproduced).

1965

Alan Bowness (ed.), Henry Moore. Volume 3: Sculpture and Drawings 1955–64, London 1965, no.470, reproduced pls.102–3.

1968

John Russell, Henry Moore, London 1968, pp.159–61 (?another cast reproduced pl.171).

1968

John Hedgecoe (ed.), Henry Moore, London 1968, p.351 (original plaster reproduced p.350, ?another cast reproduced p.351).

1968

Ionel Jianou, Henry Moore, Paris 1968 (?another cast reproduced nos.50–1).

1969

Henry Moore Exhibition in Japan, 1969, exhibition catalogue, National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo 1969, reproduced.

1969

Milton Rugoff, A Treasury of Contemporary Art, New York 1969 (?another cast reproduced p.62).

1972

Mostra di Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Forte di Belvedere, Florence 1972, reproduced p.181.

1973

John Russell, Henry Moore, London 1973, p.186 (?another cast reproduced pl.106).

1975

C.M. Clarke, ‘Three Part Object’, City of York Art Gallery Quarterly Preview, no.110, April 1975, p.979 (?another cast reproduced).

1977

Alan Bowness (ed.), Henry Moore. Volume 4: Complete Sculpture 1964–73, London 1977, p.13.

1978

The Henry Moore Gift, exhibition catalogue, Tate Gallery, London 1978, reproduced p.43.

1981

[Richard Calvocoressi], ‘T.2285 Three Part Object’, The Tate Gallery 1978–80: Illustrated Catalogue of Acquisitions, London 1981, pp.127–8.

1982

Exhibition of Drawings and Sculptures by Henry Moore, Tasende Gallery, La Jolla, September–October 1982 (another cast reproduced).

1983

W.J. Strachan, Henry Moore: Animals, London 1983 (?another cast reproduced no.31).

1987

Henry Moore and Landscape, exhibition catalogue, Yorkshire Sculpture Park, West Bretton 1987 (another cast reproduced p.21).

1987

Sam Hunter, ‘Montecarlo Sculpture 87’, Art News, vol.86, no.4, April 1987, pp.41–74 (another cast reproduced).

1998

John Hedgecoe, A Monumental Vision: The Sculpture of Henry Moore, London 1998

(?another cast reproduced pp.148–9).

(?another cast reproduced pp.148–9).

Technique and condition

This is a vertically oriented bronze sculpture mounted onto a square bronze base. The cast is hollow and the surface of the sculpture is predominantly brown although green can be seen in its crevices. The base is a slightly darker brown and is attached to the sculpture with two large screw-threaded studs fixed with hex-headed nuts.

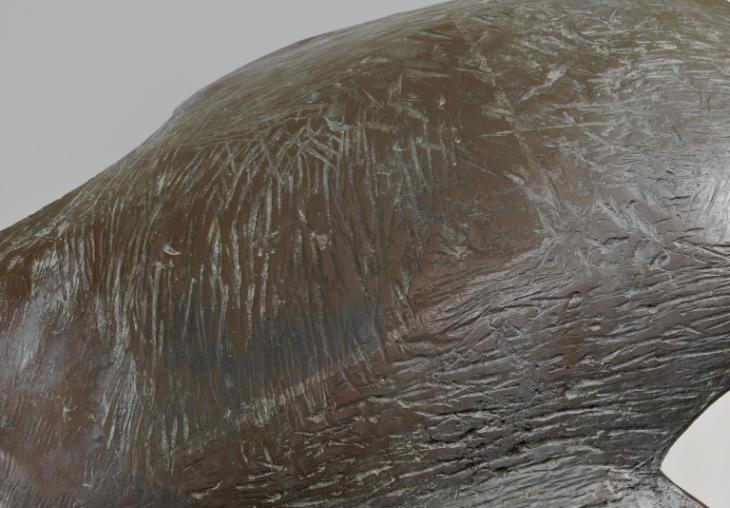

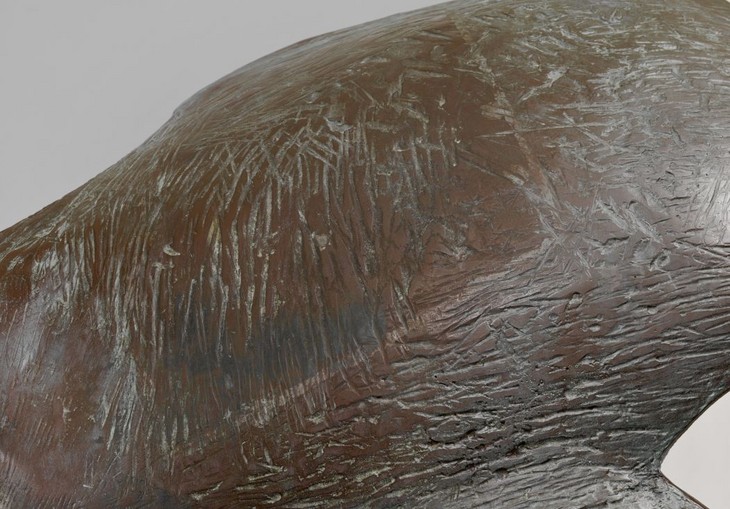

Moore made the original model for this sculpture in plaster, which was used to make the mould from which the bronze was cast. The model was made by applying successive layers of plaster to a supportive armature, which was probably constructed from metal or wood. Moore often worked into the plaster as it set to create varied surface textures. For instance, striations in the surface indicate that Moore used a tool such as a surform to cut into the plaster at the ‘cheese hard’ stage before the plaster had fully dried (fig.1). When the plaster had hardened Moore applied fine abrasives to the high points of the sculpture to achieve a smooth finish.

Detail of surface texture of Three Part Object 1960

Tate T02285

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.1

Detail of surface texture of Three Part Object 1960

Tate T02285

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

At the foundry the bronze would have been cast in multiple sections which were subsequently welded together to form the whole. There is a visible weld seam following the curved edge between the smooth and bulbous faces of the sculpture (fig.2). The base was probably sand cast, although it is not clear what casting technique was used for the sculpture itself. Weld seams were abraded down to the level of the original surface and textured to match the surrounding bronze using a range of small punch tools. This process is known as ‘chasing’. Sometimes repairs need to be made to casts if there are trapped air bubbles or other faults in the bronze. An example of one such repair can be seen in the welded patch at the top of the sculpture (fig.3).

Detail of welding seam on Three Part Object 1960

Tate T02285

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.2

Detail of welding seam on Three Part Object 1960

Tate T02285

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Detail of repair on Three Part Object 1960

Tate T02285

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.3

Detail of repair on Three Part Object 1960

Tate T02285

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

The surface of the bronze was coloured using an artificial patina. This would have required chemical solutions to be applied to the surface of the bronze, triggering a reaction that produced coloured compounds. In this case it is probable that a chemical called potassium polysulphide (often called ‘liver of sulphur’) was used. This produces a range of brown tones depending on its concentration and the amount of heat applied. A layer of light green patina was then applied over the top. The sculpture may also have been given a lacquer coating, suggested by some brownish gold highlights visible where the patina has been protected, which in turn suggest that the sculpture was originally a lighter colour. There are green run-marks in the patina on some of the lower surfaces, which indicate that the sculpture has been displayed outdoors.

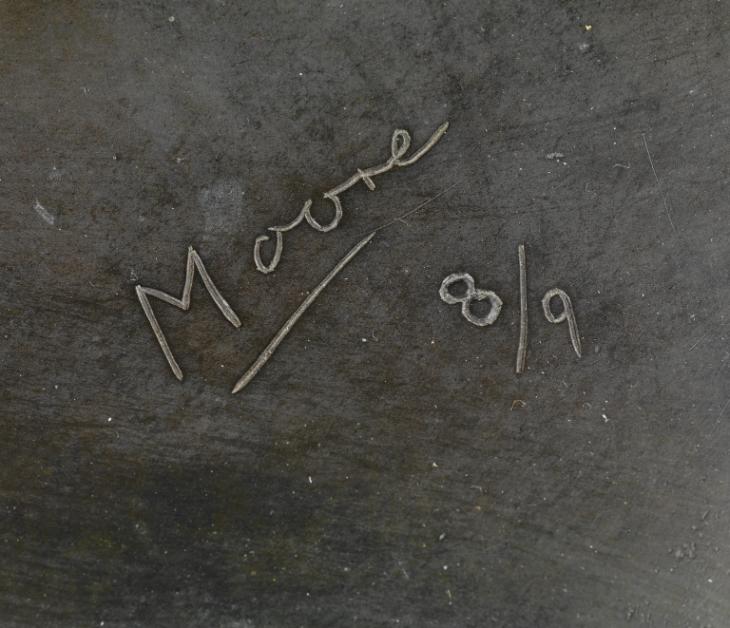

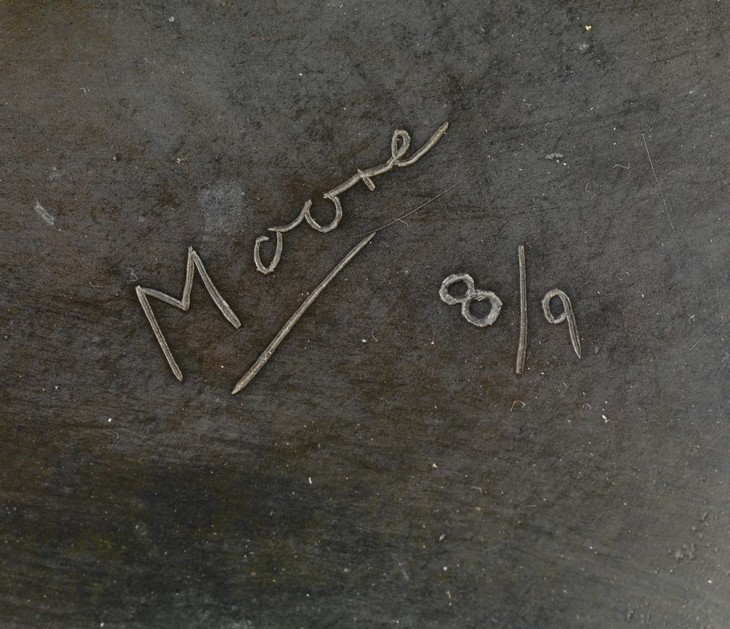

Detail of artist's signature and edition number on Three Part Object 1960

Tate T02285

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.4

Detail of artist's signature and edition number on Three Part Object 1960

Tate T02285

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

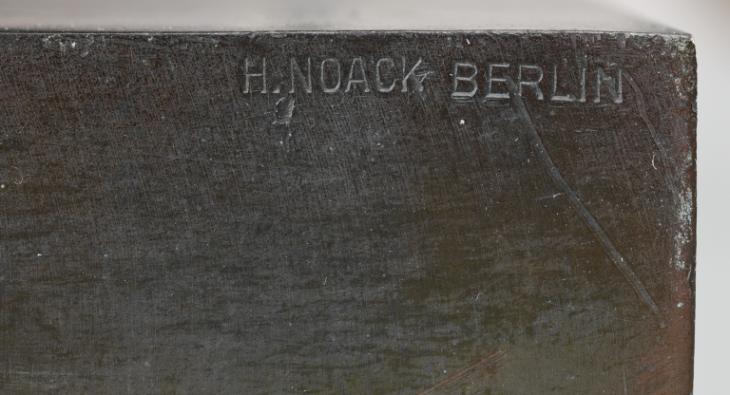

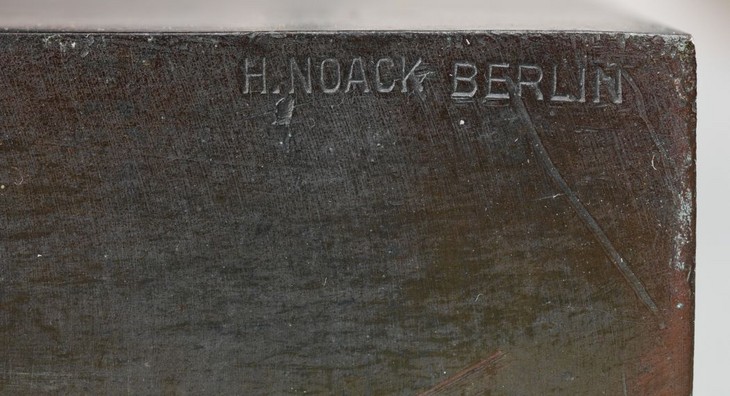

Detail of foundry stamp on Three Part Object 1960

Tate T02285

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.5

Detail of foundry stamp on Three Part Object 1960

Tate T02285

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

This sculpture was cast at the Noack Foundry in West Berlin in an edition of nine plus one artist’s proof. The artist’s signature and the number of the cast, ‘Moore 8/9’, are inscribed in a corner on the upper face of the base (fig.4). The founder’s mark ‘H. NOACK BERLIN’ is stamped just below it on an adjacent side (fig.5).

Lyndsey Morgan

March 2013

How to cite

Lyndsey Morgan, 'Technique and Condition', March 2013, in Alice Correia, ‘Three Part Object 1960 by Henry Moore OM, CH’, catalogue entry, April 2013, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015, https://wwwEntry

This sculpture comprises three irregular bulbous forms stacked on top of each other. The vertical arrangement arcs in a way that resembles a C-shape, although this is only obvious when seen from certain angles (fig.1). The outer surfaces of the curve are much flatter and smoother compared to those on the inside, which are rounder and fuller. The sculpture was designed in the round and certain features become more or less pronounced depending on the angle from which it is viewed.

Henry Moore

Three Part Object 1960

Tate T02285

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.2

Henry Moore

Three Part Object 1960

Tate T02285

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Detail of lower segment of Three Part Object 1960

Tate T02285

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.3

Detail of lower segment of Three Part Object 1960

Tate T02285

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

The upper segment is the smallest of the three and a curved recess with sharp edges has been carved into one of its faces. A thin, angular spur projects outwards from the inside of this curve, extending from the smoother lateral face. From one side it appears as though the top of the form has been cut into at right angles, creating a groove or channel that runs the length of its apex (fig.2). An almost identical recess and projecting spur appear in the same face of the middle segment, although the curve of the recess has been less sharply delineated and it covers a larger surface area. This segment is positioned on a more vertical angle than the upper form but has a very similar shape. Like the top segment, it is deeper than it is wide.

The bottom segment is a slightly different shape (fig.3). It is much fuller and rounder but has one notably flatter face, which gives it the appearance of a slightly misshapen hemisphere. Viewed from one side the whole sculpture looks precariously balanced, with only a small area of the bottom form’s rounded surface touching the base. This affect is heightened by the way the segments above curve over the base as though they are about to fall. However, the large surface areas that connect the forms, and the evenness of the sculpture’s smoother outer curve give it a formal cohesion that seem to defy the instability of the composition.

From plaster to bronze

By 1960, when Three Part Object was created, Moore had moved away from making preparatory drawings for his sculptures and had started making small three-dimensional models in plaster or other malleable materials. It is likely that Moore made the tiny plaster maquette for Three Part Object (fig.4) in the maquette studio on the grounds of his home, Hoglands, at Perry Green in Hertfordshire. This studio was lined with shelves displaying Moore’s ever growing collection of found bones, shells and flint stones, the shapes of which often served as starting points for Moore’s formal experiments in three dimensions. In 1963 he described how he worked with these objects to the critic David Sylvester:

I look at them, handle them, see them from all round, and I may press them into clay and pour plaster into that clay and get a start as a bit of plaster, which is a reproduction of the object. And then add to it, change it. In that sort of way something turns out in the end that you could never have thought of the day before.1

The shapes of the three segments suggest that Moore may have created the maquette by pushing a bone fragment into clay before filling the impression left in the clay with wet plaster. This would also serve to explain why each segment has a smoother, slightly flatter surface where the plaster reached the top of the mould.2

Once Moore was satisfied with the design of his maquette it was scaled up to a full-size plaster version. The enlargement process was probably carried out in the White Studio at Hoglands by Moore’s studio assistants, who in 1960 were Phillip King and Clive Sheppard. He was able to allocate the bulk of the enlargement work to others because, as curator Julie Summers has noted, it was ‘a scientific rather than artistic process’.3 The first stage in the scaling-up process was to take detailed measurements from the small maquette using a set square. An armature made of wood or chicken wire was then constructed according to these measurements. Successive layers of plaster were then built up over this structure and the sculpture began to gain mass and form. At this stage Moore would have taken over to finish the work and texture the surface. The bronze cast has retained the surface texture of the plaster model and demonstrates that Moore used a range of techniques to achieve the finish. The mottled texture of the recessed surfaces would have been created as the wet plaster was applied, while long striations show how Moore cut into the plaster when it had partially dried. Once the plaster was completely dry a fine tool was used to smooth the outer surfaces of the three segments.

When the plaster version was complete it was sent to the Noack Foundry in West Berlin to be cast in bronze. By 1960, when this sculpture was cast, Noack was regarded as one of the best bronze foundries able to undertake large-scale castings. Before a mould could be made of the sculpture into which molten bronze could be poured, the plaster had to be cut up into more manageable sizes and covered in sealants and resins. It is not clear whether the bronze Three Part Object was cast using the lost wax or sand casting method, but it is evident that the sculpture was cast in separate pieces and then welded together at the foundry. Seam marks where the pieces have been welded together are clearly visible on the surface (fig.5).

After it had been cast at the foundry the bronze sculpture was returned to Moore so that he could inspect the casting, sign the sculpture, and make decisions about its patination. A patina is the surface colour of a sculpture and is usually achieved by applying chemical solutions to the bronze surface. Three Part Object has a fairly consistent dark brown base patina, over which a light green patina has been applied and a golden colour may be seen on some of the sculpture’s high points. Green drip marks on the lower segment originate from the 1980s when Three Part Object was exhibited outside in the sculpture garden at Portsmouth City Art Gallery. However, these marks are minimal, and since 1991 Three Part Object has only been exhibited indoors.

Reception and interpretation

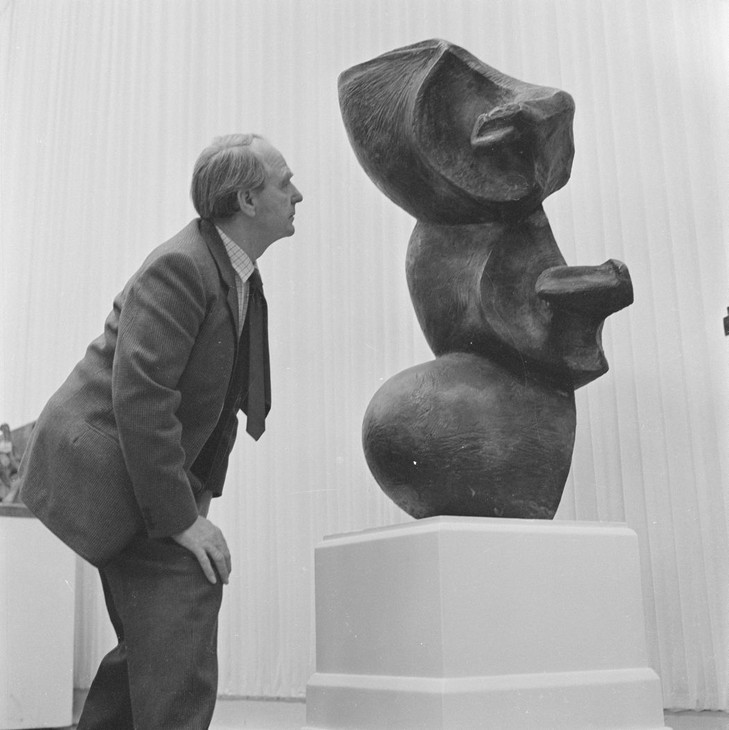

Henry Moore with Three Part Object 1960 at the Whitechapel Gallery, London, in 1960

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.6

Henry Moore with Three Part Object 1960 at the Whitechapel Gallery, London, in 1960

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Moore himself acknowledged the difficulties posed by the form of Three Part Object. In 1968 he asserted that ‘Three Part Object is a strange work, even for me. Three similar forms are balanced at angles to each other. In my mind it has a connection with insect life, possibly centipedes. Each segment has a leg, and there is an element in the sculpture nearer to an animal organism than a human one’.5 In 1973 the critic John Russell followed these inferences, aligning the sculpture with Moore’s animal forms from the 1960s, such as Large Slow Form 1962 (Tate T02290). However, Russell also cited Moore’s reluctance to make direct statements about its content:

It has a sort of animal/vegetable mixture. It’s not human, but neither is it animal or vegetable. Well, I just don’t know how it came about. I don’t know how a piece like that begins. I just begin in the morning with a bit of plaster or a bit of clay and a form comes about. Either it has some interest, and keeps it, or it doesn’t. If it has, I go on without having to know, or trying to know, exactly what it means. I wish in a way that I could be even freer than I am from the tie of having to know exactly what it means, so that I could take a form and develop it and carry it further without ever having to have an ‘explanation’.6

Three Part Object was included in a discussion of Moore’s depictions of insects in W.J. Strachan’s 1983 publication Henry Moore: Animals. Moore’s earliest animal sculpture dates from 1921 and animals of various kinds appeared as a sporadic but persistent subject throughout his career, with the last examples dating from 1982. In 1977 the art historian Alan Bowness described Three Part Object as ugly and its forms as ‘snout-like’.7 However, Bowness did not regard these characteristics in negative terms; instead he suggested that the sculpture acted as a reminder that ‘Moore has always preferred vitality to beauty’.8 Bowness’s use of the term ‘vitality’ recalled the critic Herbert Read’s comments on Moore’s animal sculptures from the 1930s, which Read believed reduced the animal subject to certain basic shapes or features ‘which best denote its vitality’.9 The concept was also used by Moore himself in a 1933 statement for the publication Unit One, in which he explained that, ‘for me a work must first have a vitality of its own. I do not mean a reflection of the vitality of life, of movement, physical action, frisking, dancing figures and so on, but that a work can have in it a pent-up energy, an intense life of its own, independent of the object it may represent’.10 This idea that ‘vitality’ conveys the essential life force of a creature more convincingly than naturalistic representation may account for the arrangement of forms in Three Part Object.

In addition to the animal and vegetable forms identified by Moore, the shapes of rocks and pebbles may have also informed Three Part Object. During the mid-1950s Moore started to become interested in flint stones he found on the grounds of his home. These flints had smoothed and rounded external surfaces, but when broken possessed sharp and jagged edges. In 1968 the critic David Sylvester noted that from 1955 ‘Moore quite suddenly started to do sculptures in which there are violent contrasts of surface tension, with exceedingly taut, bone-hard, passages moving into soft, resilient, fleshy passages, often very abruptly’.11 The sharp recesses and angular protrusions of Three Part Object may have their origins in Moore’s examination of the flints he collected and kept in his studio.

Moore had been interested in the shapes of naturally weathered stones and pebbles since the late 1920s and he subjected them to imaginative transformations in many of his sculptures and drawings of the 1930s. In 1965 the art critic Herbert Read suggested that Three Part Object constituted a return to Moore’s ‘biomorphic abstraction’ of the 1930s.12 Biomorphic abstraction refers to a mode of representation that evokes organic forms and materials and in 1936 the curator Alfred H. Barr identified it ‘as the most significant new development in international abstract art’, and singled-out Moore as one of the style’s leading practitioners.13 Although he did not use the term ‘biomorphic’, Moore explained to Tate curator Richard Calvocoressi on 12 December 1980 that ‘the free invention of forms in [Three Part Object] ... combined to produce a convincing organic whole with a life of its own’.14

Jean Arp (Hans Arp)

Pagoda Fruit 1949

Tate N06025

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.7

Jean Arp (Hans Arp)

Pagoda Fruit 1949

Tate N06025

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

The Henry Moore Gift

Three Part Object was presented by Henry Moore to the Tate Gallery in 1978 as part of the Henry Moore Gift. The Gift comprised thirty-six sculptures in bronze, marble and plaster and was exhibited in its entirety alongside Tate’s existing collection of Moore’s work in an exhibition celebrating the artist’s eightieth birthday, which opened in June 1978. A press release was duly prepared announcing that ‘The group [of sculptures] is the most substantial gift of works ever given to the Tate by an artist during his lifetime’.19 Three Part Object was included in the exhibition and was displayed in gallery nineteen alongside Working Model for Unesco Reclining Figure 1957 (Tate T00390; fig.8). The exhibition was attended by over 20,500 people and nearly 11,000 copies of the catalogue were sold.20 At its close in late August the Director of Tate, Norman Reid, reflected in a letter to Moore’s daughter Mary Danowski that although he was sad to see the exhibition come to an end ‘we have the consolation of the splendid group of sculptures which Henry has presented to the nation’.21

Installation view of The Henry Moore Gift, Tate Gallery, London 1978

Tate Archive

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.8

Installation view of The Henry Moore Gift, Tate Gallery, London 1978

Tate Archive

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

After the 1978 exhibition Tate decided that it should lend certain works from the Henry Moore Gift to regional galleries in the United Kingdom on a long-term basis.22 With Moore’s approval a list of galleries and works was drawn up and in 1979 Three Part Object was loaned to Portsmouth City Art Gallery, where it was exhibited in the gallery’s sculpture garden. In December 1980 the sculpture was knocked off its plinth in an act of willful vandalism but fell onto soft ground and was not extensively damaged. The sculpture was reinstalled in 1981 and remained at the Portsmouth City Art Gallery until 1991. At this time Three Part Object was returned to Tate, where it was examined by conservation department staff who removed stains and bird droppings that had accumulated on its surface.

Three Part Object was cast in an edition of nine plus one artist’s copy. Other examples are held in the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, and the Sunken Gardens, Yokohama. The full-size original plaster is held in the collection of the Henry Moore Foundation and the remaining casts are believed to reside in private collections.

Alice Correia

April 2013

Notes

Henry Moore cited in David Sylvester, ‘Henry Moore talking to David Sylvester’, 7 June 1963, transcript of Third Programme, BBC Radio, broadcast 14 July 1963, p.18, Tate Archive TGA 200816. (An edited version of this interview was published in the Listener, 29 August 1963, pp.305–7).

Moore is known to have recycled certain forms in different sculptures, and he is believed to have used the same bone shape from the middle section of Three Part Object in Three Figures 1982 (The Henry Moore Foundation). This sculpture fuses its three bone-like fragments along a horizontal base so that their thin spurs project upwards rather than outwards, perhaps suggesting the form of a head. James Copper, Sculpture Conservator at the Henry Moore Foundation, interview with the author, 31 July 2013.

Julie Summers, ‘Fragment of Maquette for King and Queen’, in Claude Allemand-Cosneau, Manfred Fath and David Mitchinson (eds.), Henry Moore From the Inside Out: Plasters, Carvings and Drawings, Munich 1996, p.126.

Nevile Wallis, ‘Elemental Moore’, Observer, 27 November 1960, p.27; and [David Thompson], ‘Mr Henry Moore’s Exhilarating Exhibition’, Times, 28 November 1960, p.6.

Alan Bowness, ‘Introduction’, in Alan Bowness (ed.), Henry Moore. Volume 4: Complete Sculpture 1964–73, London 1977, p.13.

Henry Moore, ‘Statement for Unit One’, in Herbert Read (ed.), Unit One: The Modern Movement in English Architecture, Painting and Sculpture, London 1934, pp.29–30, reprinted in Alan Wilkinson (ed.), Henry Moore: Writings and Conversations, Aldershot 2002, p.192.

See Christopher Green, ‘Henry Moore and Picasso’, in James Beechy and Chris Stephens (eds.), Picasso and Modern British Art, exhibition catalogue, Tate Britain, London 2012, p.139.

[Richard Calvocoressi], ‘T.2285 Three Part Object’, The Tate Gallery 1978–80: Illustrated Catalogue of Acquisitions, London 1981, p.128.

Carola Giedion-Welcker, ‘Arp: An Appreciation’ in James Thrall Soby (ed.), Arp, exhibition catalogue, Museum of Modern Art, New York 1958, p.21.

Related essays

- Scale at Any Size: Henry Moore and Scaling Up Rachel Wells

- Circling Each Other: Henry Moore and Adrian Stokes Richard Read

- Henry Moore: The Plasters Anita Feldman

- At the Heart of the Establishment: Henry Moore as Trustee Julia Kelly

- Henry Moore's Approach to Bronze Lyndsey Morgan and Rozemarijn van der Molen

Related catalogue entries

How to cite

Alice Correia, ‘Three Part Object 1960 by Henry Moore OM, CH’, catalogue entry, April 2013, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015, https://www