Henry Moore OM, CH Maquette for Standing Figure 1950, cast 1956

Image 1 of 10

-

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Standing Figure 1950, cast 1956© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Standing Figure 1950, cast 1956© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Standing Figure 1950, cast 1956© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Standing Figure 1950, cast 1956© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Standing Figure 1950, cast 1956© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Standing Figure 1950, cast 1956© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Standing Figure 1950, cast 1956© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Standing Figure 1950, cast 1956© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Standing Figure 1950, cast 1956© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Standing Figure 1950, cast 1956© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Standing Figure 1950, cast 1956© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Standing Figure 1950, cast 1956© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Standing Figure 1950, cast 1956© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Standing Figure 1950, cast 1956© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Standing Figure 1950, cast 1956© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Standing Figure 1950, cast 1956© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Standing Figure 1950, cast 1956© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Standing Figure 1950, cast 1956© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Standing Figure 1950, cast 1956© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Standing Figure 1950, cast 1956© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH,

Maquette for Standing Figure

1950, cast 1956

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Maquette for Standing Figure 1950, cast 1956 is the small model for a larger bronze sculpture titled Standing Figure. For this work Moore exploited the strength and malleable properties of bronze to create a wiry, skeletal human form that critics have argued expresses a sense of menace or anxiety attributed to the post-war era.

Henry Moore OM, CH 1898–1986

Maquette for Standing Figure

1950, cast 1956

Bronze on a pine wood base

275 x 94 x 75 mm

Presented by Gustav and Elly Kahnweiler in 1974, accessioned 1994

Number 1 in an edition of 7 plus 1 artist’s copy

T06827

Maquette for Standing Figure

1950, cast 1956

Bronze on a pine wood base

275 x 94 x 75 mm

Presented by Gustav and Elly Kahnweiler in 1974, accessioned 1994

Number 1 in an edition of 7 plus 1 artist’s copy

T06827

Ownership history

Acquired directly from the artist by Gustav and Elly Kahnweiler in 1956, by whom presented to Tate in 1974, accessioned 1994.

Exhibition history

2004–5

Cubism and its Legacy: The Gift of Gustav and Elly Kahnweiler, Tate Modern, London, May–November 2004; Tate Liverpool, Liverpool, December 2004–May 2005, no.43.

2007–10

Henry Moore: Textiles, Dovecot Studios, Edinburgh, November 2008–January 2009; Henry Moore Foundation, Perry Green, April–October 2009; Pallant House Gallery, Chichester, November 2009–February 2010; Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts, Norwich, June–August 2010.

References

1951

David Sylvester (ed.), Sculpture and Drawings by Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Tate Gallery, London 1951, no.134.

1951

Catalogue of an Exhibition of New Bronzes and Drawings by Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Leicester Galleries, London 1951, no.4.

1951

Sculpture: An Open Air Exhibition, exhibition catalogue, Battersea Park, London 1951, pp.57–9 (Standing Figure 1950 reproduced).

1952

Kenneth Clark, Philip Hendy and Herbert Read, The British Pavilion, exhibition catalogue, Venice Biennale, Venice 1952.

1958

A Sculptor’s Landscape, dir. by John Read, television programme, broadcast BBC, 29 June 1958, http://www.bbc.co.uk/archive/henrymoore/8802.shtml, accessed 7 February 2014.

1959

Erich Neumann, The Archetypal World of Henry Moore, London 1959, pp.106–7 (Standing Figure 1950 reproduced no.74).

1960

Will Grohmann, The Art of Henry Moore, London 1960 (Standing Figure 1950 reproduced pl.148).

1965

Herbert Read, Henry Moore: A Study of his Life and Work, London 1965, pp.170–3 (Standing Figure 1950 reproduced pl.150).

1970

Robert Melville, Henry Moore: Sculpture and Drawings 1921–1969, London 1970, p.24 (Standing Figure 1950 reproduced pls.408–9, 411).

1977

David Finn, Henry Moore: Sculpture and Environment, New York 1977, pp.292–7 (Standing Figure 1950 reproduced).

1979

Alan G. Wilkinson, The Moore Collection in the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto, Toronto 1979, p.113 (Standing Figure 1950, cast 1970 reproduced p.112).

1986

Alan Bowness (ed.), Henry Moore. Volume 2: Complete Sculpture 1949–54, 1955, revised edn, London 1986, p.32, no.290a.

1993

John McEwen, Glenkiln, Edinburgh 1993, pp.34–43 (Standing Figure 1950 reproduced).

2004

Giorgia Bottinelli, ‘Henry Moore’, in Jennifer Mundy (ed.), Cubism and its Legacy: The Gift of Gustav and Elly Kahnweiler, exhibition catalogue, Tate Modern, London 2004, pp.82–7, reproduced p.85.

2004

Ian Dejardin, ‘The Human Form – Standing Figures’, in Henry Moore at Dulwich Picture Gallery, exhibition catalogue, Dulwich Picture Gallery, London 2004, p.162.

2006

Giovanni Carandente, ‘Standing Figure 1950’, in David Mitchinson (ed.), Celebrating Moore: Works from the Collection of the Henry Moore Foundtion, London 2006, pp.226–7 (Standing Figure 1971 reproduced).

2006

Robert Burstow, ‘Modern Sculpture in the Public Park: A Socialist Experiment in Open Air “Leisured Culture”’, in Patrick Eyres and Fiona Russell (eds.), Sculpture and the Garden, London 2006, pp.133–44.

2008

Christa Lichtenstern, Henry Moore: Work-Theory-Impact, London 2008, pp.330–3.

Technique and condition

Henry Moore

Maquette for Standing Figure 1950

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Alice Correia

Fig.1

Henry Moore

Maquette for Standing Figure 1950

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Alice Correia

Detail of Maquette for Standing Figure 1950, cast 1956 showing modelling marks on surface

Tate T06827

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.2

Detail of Maquette for Standing Figure 1950, cast 1956 showing modelling marks on surface

Tate T06827

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

This small bronze sculpture developed from a model made of plasticine built up over an internal wire armature, which provided support for the delicate thin forms (fig.1). This model would have been used to create a mould from which the sculpture could be cast in bronze. It is likely that the sculpture was cast using the lost wax technique because the surface of the bronze, which is mostly smooth, features some light modelling marks that were clearly reproduced from the original model (fig.2). The surface has been chased to remove seam lines created during the casting process but otherwise does not bear many marks of post-cast finishing. There are no foundry marks or inscriptions visible.

The bronze has been chemically patinated with an opaque green colour, while a dark transparent brown colour can be seen on the high points (fig.3). The brown patina was applied first, probably using a solution of potassium polysulphide and water (otherwise known as ‘liver of sulphur’). This was then followed by the application of a different chemical solution to produce the green patina. There are many recipes for green patinas but they usually contain a mixture of copper and ammonium salts, particularly chorides, in water. These are stippled on with a brush and react with the bronze surface to create colourful green copper compounds. Patinas like these are usually applied in a number of layers until the desired colour is achieved. In the case of this sculpture the green patina was rubbed back using a light abrasive to reveal the underlying brown patina on the high points. After patination a layer of wax was applied to protect the surface.

The sculpture has its own integral bronze base secured onto a 12 mm thick rectangular pine base by means of a single countersunk screw inserted from the underside. The pine base is stained dark grey but the wood grain is clearly visible and has not been sealed with a varnish.

Lyndsey Morgan

March 2011

How to cite

Lyndsey Morgan, 'Technique and Condition', March 2011, in Alice Correia, ‘Maquette for Standing Figure 1950, cast 1956 by Henry Moore OM, CH’, catalogue entry, February 2014, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015, https://wwwEntry

Detail of Maquette for Standing Figure 1950, cast 1956 showing modelling marks on surface

Tate T06827

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.1

Detail of Maquette for Standing Figure 1950, cast 1956 showing modelling marks on surface

Tate T06827

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

At the base of the necks two flat, triangular forms protrude from the front and the back of the figure respectively and may represent a chest and a shoulder blade. Although they are roughly the same size and shape, these two forms are positioned at different angles so that the planes appear to overlap from certain positions. The empty space of the torso below is outlined by two wiry forms, which may also connote arms. They extend downwards, meeting at the hip or pelvis area, which is denoted by a disk tilted at an angle. From this intersection extend two thin legs, bridged at the mid-point by a horizontal bar. The legs terminate at a single, oval-shaped disk, which is attached to the wooden base.

Although the psychologist Erich Neumann argued in 1959 that this sculpture had ‘only a very distant resemblance to the human form’, in 1965 the art critic Herbert Read described it as definitively human.1 For Read, Moore had split ‘the human frame along the lines of force indicated by arms and legs with a nodular joint at the shoulders, hips and knees. The shoulder-blades are extruded as triangular wedges, which the neck is again split to end in two antennae-like heads’.2

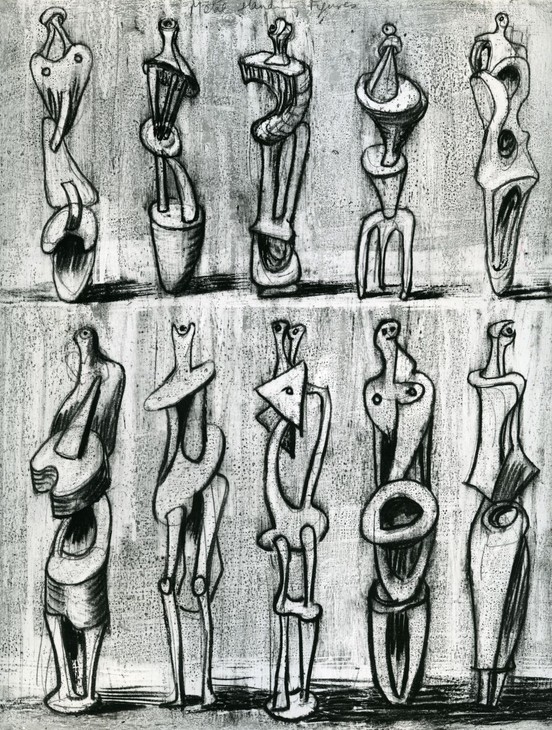

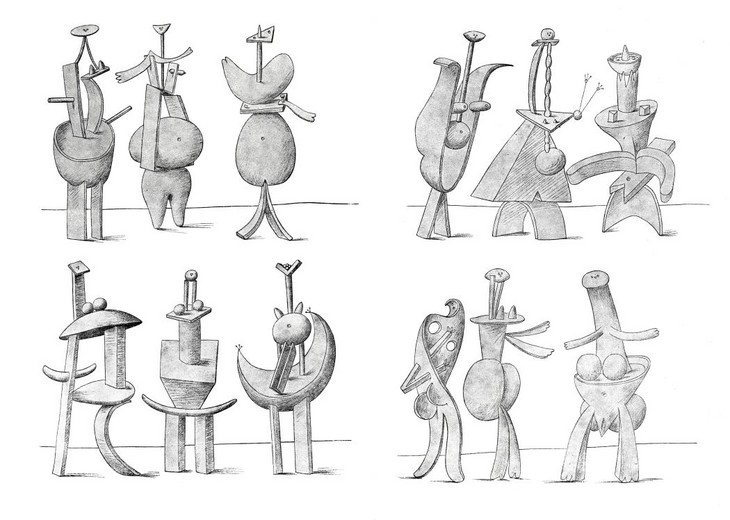

Henry Moore

Ideas for Metal Standing Figures 1947–9

Graphite, wax crayon, coloured crayon, watercolour wash, brush and ink on paper

292 x 242 mm

Private collection

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.2

Henry Moore

Ideas for Metal Standing Figures 1947–9

Private collection

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore

Maquette for Standing Figure 1950

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Alice Correia

Fig.3

Henry Moore

Maquette for Standing Figure 1950

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Alice Correia

Detail of patina on Maquette for Standing Figure 1950, cast 1956

Tate T06827

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.4

Detail of patina on Maquette for Standing Figure 1950, cast 1956

Tate T06827

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

To make Maquette for Standing Figure Moore first had to create a model from which a mould could be taken to cast the sculpture in bronze. This model was made of plasticine built over a wire armature. Although the model has survived, over time the plasticine has become brittle and only fragments of the material exist (fig.3). However, the tool marks on the surface of the two bronze triangles were reproduced from the original model and thus reveal how Moore shaped the plasticine. This level of detail suggests that the bronze was cast using the lost wax technique.5 Moore did not cast this sculpture himself but employed the Fiorini Art Bronze Foundry in London to undertake the work in 1956, six years after the original model was made.6

After casting the bronze sculpture Fiorini would have returned it to Moore so that he could check the quality of the cast and make decisions about the patina. A patina is the surface colour of a sculpture and is usually achieved by applying chemical solutions to the pre-heated bronze. Maquette for Standing Figure has been patinated an opaque green colour, which has been stippled onto the bronze (fig.4). The chemicals required to create the green colour would have been applied in a number of layers over a darker brown solution. The green was then rubbed back at certain points, such as along the edges of the triangle, to reveal the brown colour beneath. A coat of wax has since been applied to protect and maintain the patina.

In 1965 Herbert Read noted that the diffusion of Moore’s small bronzes ‘to collectors and museums throughout the world helped to establish the fame of the sculptor’.7 By the mid-1950s Moore’s work was also in much greater demand by collectors and patrons and producing smaller works in editions of eight or nine would have been a practical way of catering to this popularity. During the 1950s Moore worked with a number of different London-based commercial galleries including Roland Browse and Delbanco, Gimpel Fils and the Leicester Galleries, all of which sold small sculptures by Moore that could be placed on table tops within the home. Depending on the demand for particular works Moore would either cast the full edition in one batch or cast more examples as others were sold, known as casting on demand. By the time Moore cast Maquette for Standing Figure the full-size version of the sculpture had become well known, having been included in a number of important exhibitions, and it seems that demand for the maquette was strong. According to records held at the Henry Moore Foundation Tate’s cast is number one of the edition, and the original owners, Gustav and Elly Kahnweiler, collected the work from Moore’s studio on 31 July 1956.8 The eighth and final bronze in the edition was acquired by Gimpel Fils in June 1957.9 It is believed that the other examples of this sculpture are held in private collections.

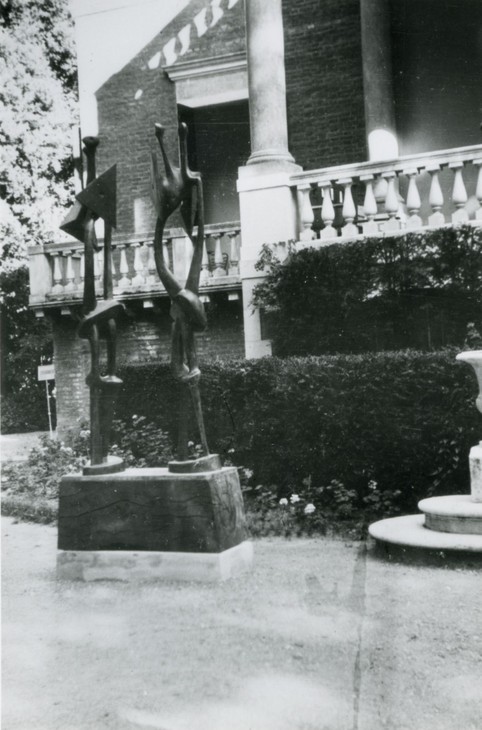

Henry Moore

Standing Figure 1950

Bronze

Glenkiln Estate, Shawhead, Scotland

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.5

Henry Moore

Standing Figure 1950

Glenkiln Estate, Shawhead, Scotland

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore

Stringed Figure 1938

Lignum vitae and string

Whereabouts unknown

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.6

Henry Moore

Stringed Figure 1938

Whereabouts unknown

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Maquette for Standing Figure was the preparatory model for a much larger sculpture, Standing Figure 1950 (fig.5), which was cast in bronze in an edition of four. By the time Moore had finished the maquette, he had already intended to create the work on a larger scale. In 1968 he explained to the photographer John Hedgecoe:

When I make a small maquette, it is rather like an architect making a sketch for a building on an envelope. In his mind it is a full-size building. In the same way, with my small plaster maquettes, I am thinking of something much larger. By looking at a maquette close to, I can relate it to some distant object and imagine it as huge. It’s all a question of mental scale and not physical size.10

Maquette for Standing Figure marked a return to a mode of figurative representation that Moore had first developed in his sculptures of the late 1930s. In works such as Reclining Figure 1939 (Tate T00387; fig.6) the human body was rendered as a skeletal form comprising thin rods and wiry shapes. The opening out of the torso and rib-cage and the consequent creation of internal spaces was explored in Moore’s figurative sculpture throughout the 1930s and may have stimulated his later interest in the relationships between internal and external forms seen in his works of the 1950s (see Upright Internal/External Form 1952–3, Tate T02272). However, Moore’s ambition to open out the sculpture presented technical problems when working in stone and wood, which were only resolved by Moore’s turn to metal casting in 1937–8. Working in wax or plasticine enabled Moore to create much thinner forms than those that were possible in stone, and he observed in 1960 that working in this way allowed sculptors to make ‘spatial forms’.11 As Read explained in 1965:

Moore became fascinated by what he has called ‘the bronze thing’ – that is to say, the forms natural to a casting in this metal. The change of technique involved a change in approach: it was no longer a question of the material (stone) imposing its qualities on the ideas of the sculptor: the ideas could now be rendered without physical compromise into a ductile material.12

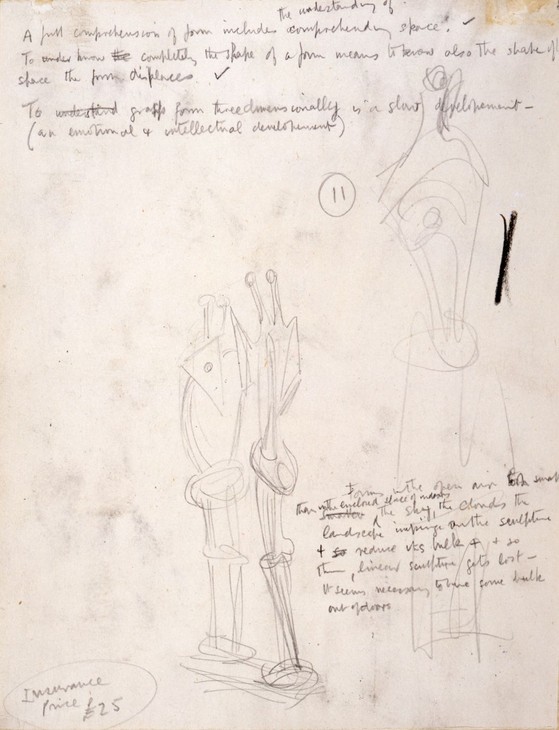

Henry Moore

Sketches of Standing Figure 1950–1

Graphite on paper

290 x 240 mm

Private collection

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.7

Henry Moore

Sketches of Standing Figure 1950–1

Private collection

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Double Standing Figure 1950 at the entrance to the British Pavilion, Venice Biennale, 1952

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: British Council

Fig.8

Double Standing Figure 1950 at the entrance to the British Pavilion, Venice Biennale, 1952

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: British Council

The problem of establishing three-dimensional presence without creating massive solid forms preoccupied Moore in the early 1950s. A sketch showing the design of Standing Figure from two different angles (fig.7) is annotated with Moore’s thoughts about the relationship between the sculptural object and the space around it: ‘A full comprehension of form includes comprehending the understanding of space. To know completely the shape of a form means to know also the shape of the space the form displaces. To grasp form three dimensionally is a slow development (an emotional & intellectual development)’.13 This sketch is dated 1950–1 in the artist’s catalogue raisonné, and although its exact date is unknown, it was probably made in 1950.14 To the right of the two views of Standing Figure is another of Moore’s hand-written notes, stating: ‘Forms in the open air look smaller than in the enclosed space of indoors. The sky, the clouds, the landscape impinge on the sculpture & reduce its bulk & so thin linear sculpture gets lost – it seems necessary to have some bulk out of doors’.15

As his double drawing of Standing Figure suggests, Moore sought to overcome the problem of losing sight of his thin vertical figures within a landscape by doubling their bulk; he reasoned that ‘in theory, the double figure with its greater bulk should be more effective in an open setting than the single figure’.16 In 1955 Moore recalled that when the full-size sculpture was returned to his studio having been displayed at Battersea Park in 1951, ‘a second cast of it had already arrived from the bronze foundry, and having them both in the studio I was able to try out a double figure arrangement’.17 Double Standing Figure 1950 presents two casts of the large sculpture positioned in relation to each other and was exhibited outside the British Pavilion at the Venice Biennale in 1952 (fig.8).18

Stylistically, the open and linear figurative forms found in Maquette for Standing Figure may have been made in response to Pablo Picasso’s fragmentation of the body. Moore had been aware of Picasso’s work since his student days at Leeds School of Art, and in 1973 reflected that ‘really all my practicing life was as a student, and as a sculptor I have been very conscious of Picasso because he dominated sculpture and painting – even sculpture as well as painting – since Cubism’.19 According to the art historian Christopher Green, Moore was able to respond to Picasso’s drawings and paintings because both artists rooted their art ‘in their knowledge of the human body, however far they moved from straight representation’.20

Pablo Picasso

An Anatomy 1933

Reproduced in Minotaure, no.1, 1933, pp.36–7

Fig.9

Pablo Picasso

An Anatomy 1933

Reproduced in Minotaure, no.1, 1933, pp.36–7

While Picasso’s drawings utilise apparently man-made forms, in his analysis of the full-size Standing Figure the art historian Will Grohmann described Moore’s sculpture as ‘organic’, and suggested that he was probably thinking about ‘how something may grow out of a pair of supports’.22 Noting the way in which the pair of legs is replicated by a pair of thin forms at the torso, Grohmann suggested that ‘the head must [also] ... be double, according to the rules of the figure’.23 Following this interpretation the presence of two heads or eyes was not a contrivance to render the body more abstract, but the consequence of cohering to the rhythms and structures of the lower sections of the sculpture. As Erich Neumann suggested the year before in his analysis of Standing Figure and Double Standing Figure, ‘no doubt the formal motif of duplication and correspondence plays its part in the structure of these beings, who look like a cross between the organic and the supernatural’.24

Neumann’s analysis of Standing Figure extended from his interpretation of the drawing from which it originated. According to Neumann, the sketches in Ideas for Metal Standing Figures represented a ‘death goddess’:

Here the earth and death goddess is rising up in wrath – a goddess of the atom bomb, of the terrible destructive power of matter, which is at the same time the phantasmal power of destruction lurking in the human psyche. Everything that makes for organic synthesis and growth, development and life, is mocked and denied in a grotesque and almost insane way. This extreme and most frightful manifestation of the Great Goddess may possibly be connected with the despair that seized Western man when he realised that the Second World War and the conquest of Nazism with so much sacrifice had not brought peace, but that the will for destruction is a fundamental expression of humanity in our dark and violent age.25

Although Read concurred with much of Neumann’s analysis, he reported in 1965 that ‘Moore once told me that the preliminary idea had come from a photograph he had seen of some tall African tribesmen who stand perfectly still in the marshes of a river delta intent on spearing fishes’.26 But, like Neumann, Read also asserted that none of Moore’s sculptures made between 1945 and 1948 ‘prepares us for the radical innovation of the Standing Figures of 1950’.27 Although Read had discussed earlier works such as Reclining Figure 1939 in his book, he suggested that in light of the benevolent Madonna and Child series of 1943 (see Tate N05600–N05603), Standing Figure and its associated drawings and sculptural variations seemed to mark a significant shift in Moore’s sculptural style and subject matter. Read asserted that ‘the sculptor has endowed the form with overtones of watchfulness, of expectancy, of menace’.28

In 2010 the curator Richard Calvocoressi also addressed the sense of apprehension detected in Standing Figure by discussing the sculpture within the context of the Second World War. Calvocoressi argued that in the immediate post-war period ‘the impact of the Holocaust can be sensed in Moore’s own work’, especially in his drawings, wherein ‘his ideas for sculpture show him developing a more troubling conception of the figure as skeletal and transparent’. 29 The decimated and fragmented body had emerged as an evocative subject for many artists working at this time. Seen through the context of war, Moore’s ‘lean, skeletonic’ sculpture can be considered alongside the wiry standing figures of Robert Adams and Reg Butler. Positioned outside the British Pavilion at the 1952 Venice Biennale, Moore’s Double Standing Figure 1950 stood as the introduction to an exhibition comprising sculptures expressive of a pervasive post-war anxiety. Works by Adams, Butler, Lynn Chadwick and others expressed the ‘geometry of fear’ with their spiky, linear, metal forms, and according to Herbert Read writing in the exhibition’s catalogue, Moore was ‘in some sense no doubt the parent of them all’.30

Despite these considerations, the relationship between Standing Figure and the landscape remains the dominant mode of interpretation for both the maquette and the full-size version. In 1951 the full-size sculpture was displayed outside in Battersea Park (fig.10). In 1970 the critic Robert Melville reflected on seeing Standing Figure ‘in a Battersea Park exhibition during a dull wet summer’, arguing that:

the tall, lean Standing Figure has a somewhat stridently avant-garde appearance in a museum; one is made too aware of the problems involved in making an ‘opened-out sculpture that is neither a mass pierced by voids, not a linear structure in space’. It was transformed when it was situated heron-like on the grass verge of the pool in Battersea Park and was at its best on days when it rained and a mist crept over the surface of the pool.31

In his catalogue for the Tate’s 1951 exhibition, Moore stated that, ‘Sculpture is an art of the open air. Daylight, sunlight is necessary to it, and for me it is the best setting and complement to nature. I would rather have a piece of my sculpture put in a landscape, almost any landscape, than in, or on, the most beautiful building I know’.32

The first cast of Standing Figure originally displayed in Battersea Park was bought by W.J. Keswick and was positioned on his estate, Glenkiln, in Shawhead, Scotland, from 1951 until its theft in 2013 (see fig.5). Moore’s appreciation for the display of sculpture in a landscape was cemented when he visited Glenkiln. Although he initially thought that a double figure would be more successful in an open-air setting, in 1955 he acknowledged that:

the extreme openness of the Scottish setting for the single figure has upset whatever preconceptions I had. In the bleak and lonely setting of a grouse moor the figure itself becomes an image of loneliness, and on its outcrop of rock, its lean, skeletonic forms stand out sharp and clear against the sky, looking as if stripped to the bone by the winds of several centuries.33

Such was Moore’s satisfaction with the position of the sculpture, the maquette was also known as ‘Keswick small version’ in his sales log book.34

Henry Moore

Standing Figure 1950 installed at Glenkiln

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.11

Henry Moore

Standing Figure 1950 installed at Glenkiln

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

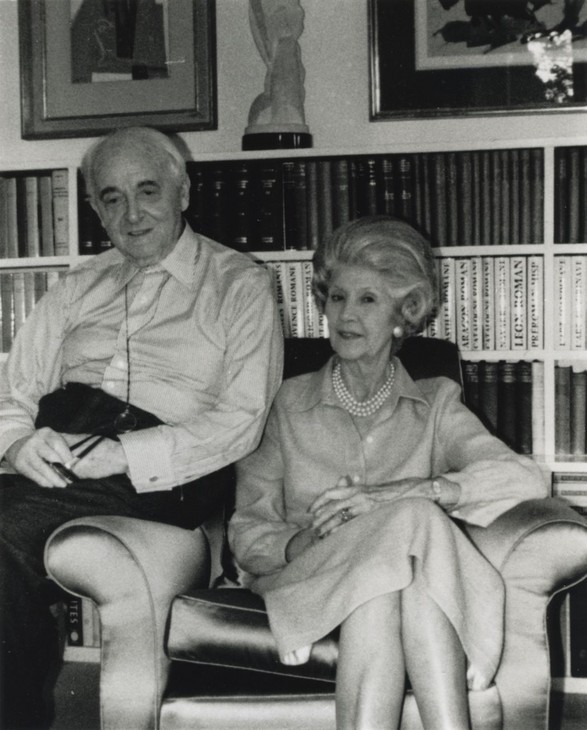

Gustav and Elly Kahnweiler at Alderbourne Manor, Buckinghamshire

Tate Archive TGA 9223.3.28

Fig.12

Gustav and Elly Kahnweiler at Alderbourne Manor, Buckinghamshire

Tate Archive TGA 9223.3.28

In 1954 the critic Robert Melville wrote that in Glenkiln, Standing Figure ‘leads a less restricted life than if it were in a museum: it is not an exhibit but a queer landmark which can be closely examined and still retain the unexaminable look of an apparition’.35 Similarly, in 1959 Neumann wrote that ‘when we see the wonderful figure standing alone in the Scottish landscape, the unique quality of these strange bronzes strikes us at once. For all its bizarre shape, no one can deny that it combines grace with monumentality ... this supernatural being stands there keeping watch over the moors’.36 Both these interpretations of the sculpture as somehow mystical and intrinsically related to the landscape were supported by atmospheric black and white photographs taken by Moore showing the sculpture at Glenkiln (fig.11).

Maquette for Standing Figure was presented to the Tate by Gustav and Elly Kahnweiler (fig.12).37 In the 1950s and 1960s the Kahnweilers were among the few art collectors in the United Kingdom who actively supported the work of European modern artists and they amassed a large collection of paintings and sculptures by artists including Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque, and Fernand Léger. Partly as a result of their friendship with the Tate director Sir John Rothenstein and with his successor Sir Norman Reid they decided to leave their entire art collection to the gallery after their deaths. A Trust Deed was signed in 1974, immediately after which a group of works were passed over to Tate. Gustav died in 1989 and the remaining works, including Maquette for Standing Figure, were accessioned into the Tate’s collection in 1994 following Elly’s death in 1991.

It is not known how or when the Kahnweilers first met Henry Moore, but they may have become familiar with his work in the late 1930s when Moore exhibited at the Mayor Gallery in London, one of the few commercial galleries that actively exhibited and supported the work of modern artists working in Britain and continental Europe. Nonetheless, by the 1950s the Kahnweilers, Moore and Moore’s wife Irina shared a warm friendship. As well as purchasing works by Moore for their own collection, Gustav acted occasionally as an agent in the sale of Moore’s sculptures. For example, in 1952 he negotiated the sale of Moore’s sculpture to the Kunstmuseum in Basel. The Kahnweilers acquired Maquette for Standing Figure directly from Moore shortly after it was cast, and it remained in their apartment at Alderbourne Manor, Buckinghamshire, where the couple had lived since 1956, until it entered the Tate’s collection.

When he died Gustav left detailed instructions regarding the Tate’s gift, and following Elly’s death a total of fifty-five artworks entered the Tate’s collection, including works by Georges Braque, Paul Klee, Henri Laurens, André Masson and Picasso. Along with Maquette for Standing Figure, four other sculptures by Henry Moore were included in the Kahnweiler Gift: Maquette for Fallen Warrior 1956 (Tate T06824), Maquette for Figure on Steps 1956 (Tate T06828), Draped Reclining Woman 1957–8 (Tate T06825), and Reclining Figure: Bunched 1961 (Tate T06826).

Alice Correia

February 2014

Notes

Henry Moore cited in ‘Henry Moore Talking to David Sylvester’, 7 June 1963, transcript of Third Programme, broadcast BBC Radio, 14 July 1963, Tate Archive TGA 200816, p.16. Moore evidently thought that this drawing was successful and recreated it as a lithographic print, Red and Blue Standing Figures 1950 (The Henry Moore Foundation). See http://catalogue.henry-moore.org:8080/emuseum/view/objects/asitem/Objects@17732/0?t:state:flow=3f0b836c-0e61-4fb7-b2b3-21e72967c749 , accessed 10 February 2014.

For a video explaining the lost wax process see http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/articles/s/sculpture-techniques/ , accessed 23 January 2014.

In addition to casting new works, from c.1955 Moore re-cast in bronze a number of small sculptures that had originally been made in lead during the 1930s (see Reclining Figure 1939, Tate T00387). Although this maquette was cast in 1956, six years after the plasticine model was created, this time-lag should not be regarded as unusual given the volume of casting Moore was overseeing during this period.

Henry Moore cited in Donald Hall, ‘Henry Moore: An Interview by Donald Hall’, Horizon, November 1960, reprinted in Alan Wilkinson (ed.), Henry Moore: Writings and Conversations, Aldershot 2002, p.233.

Transcript provided in Ann Garrould (ed.), Henry Moore. Volume 4: Complete Drawings 1950–76, London 2003, p.36.

Henry Moore, ‘Sculpture in the Open Air: A Talk by Henry Moore on his Sculpture and its Placing in Open-Air Sites’, March 1955, Tate Artist Catalogue File, Henry Moore, A23941, reprinted in Philip James (ed.), Henry Moore on Sculpture, London 1966, p.109.

For an extended discussion of the British Pavilion at the 1952 Venice Biennale see Jennifer Powell, ‘A Coherent, National “School” of Sculpture? Constructing Post-War New British Sculpture through Exhibition Practices’, Sculpture Journal, vol.21, no.2, 2012, pp.37–50.

Henry Moore, ‘Interview with Elizabeth Blunt’, Kaleidoscope, radio programme, broadcast BBC Radio 4, 9 April 1973, transcript reprinted in Wilkinson 2002, p.167.

Christopher Green, ‘Henry Moore and Picasso’, in James Beechy and Chris Stephens (eds.), Picasso and Modern British Art, exhibition catalogue, Tate Britain, London 2012, p.131.

See Minotaure, no.1, 1933, pp.36–7. For further discussion on Moore’s familiarity with French periodicals, including Minotaure, see Julia Kelly, ‘The Unfamiliar Figure: Henry Moore in French Periodicals of the 1930s’, in Jane Beckett and Fiona Russell (eds.), Henry Moore: Critical Essays, Aldershot 2003, pp.43–65.

Richard Calvocoressi, ‘Moore, the Holocaust and Cold War Politics’, in Chris Stephens (ed.), Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Tate Britain, London 2010, pp.74–5.

Herbert Read, ‘New Aspects of British Sculpture’, in Exhibition of Works by Sutherland, Wadsworth, Adams, Armitage, Butler, Chadwick, Clarke, Meadows, Moore, Paolozzi, Turnbull.Organised by the British Council for the XXVI Biennale, Venice, exhibition catalogue, Venice Biennale, Venice 1952, unpaginated.

Henry Moore cited in David Sylvester (ed.), Sculpture and Drawings by Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Tate Gallery, London 1951, p.4.

Robert Melville, ‘Henry Moore and the Siting of Public Sculpture’, Architectural Review, February 1954, p.89.

Related essays

- Henry Moore and ‘Sculpture in the Open Air’: Exhibitions in London’s Parks Jennifer Powell

- Scale at Any Size: Henry Moore and Scaling Up Rachel Wells

- At the Heart of the Establishment: Henry Moore as Trustee Julia Kelly

- Erich Neumann on Henry Moore: Public Sculpture and the Collective Unconscious Tim Martin

- ‘A sincere academic modern’: Clement Greenberg on Henry Moore Courtney J. Martin

Related catalogue entries

Related material

How to cite

Alice Correia, ‘Maquette for Standing Figure 1950, cast 1956 by Henry Moore OM, CH’, catalogue entry, February 2014, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015, https://www