Henry Moore OM, CH King and Queen 1952-3, cast 1957

Image 1 of 14

-

Henry Moore OM, CH, King and Queen 1952-3, cast 1957© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, King and Queen 1952-3, cast 1957© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, King and Queen 1952-3, cast 1957© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, King and Queen 1952-3, cast 1957© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, King and Queen 1952-3, cast 1957© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, King and Queen 1952-3, cast 1957© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, King and Queen 1952-3, cast 1957© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, King and Queen 1952-3, cast 1957© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, King and Queen 1952-3, cast 1957© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, King and Queen 1952-3, cast 1957© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, King and Queen 1952-3, cast 1957© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, King and Queen 1952-3, cast 1957© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, King and Queen 1952-3, cast 1957© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, King and Queen 1952-3, cast 1957© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, King and Queen 1952-3, cast 1957© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, King and Queen 1952-3, cast 1957© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, King and Queen 1952-3, cast 1957© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, King and Queen 1952-3, cast 1957© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, King and Queen 1952-3, cast 1957© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, King and Queen 1952-3, cast 1957© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, King and Queen 1952-3, cast 1957© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, King and Queen 1952-3, cast 1957© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, King and Queen 1952-3, cast 1957© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, King and Queen 1952-3, cast 1957© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, King and Queen 1952-3, cast 1957© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, King and Queen 1952-3, cast 1957© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, King and Queen 1952-3, cast 1957© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, King and Queen 1952-3, cast 1957© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

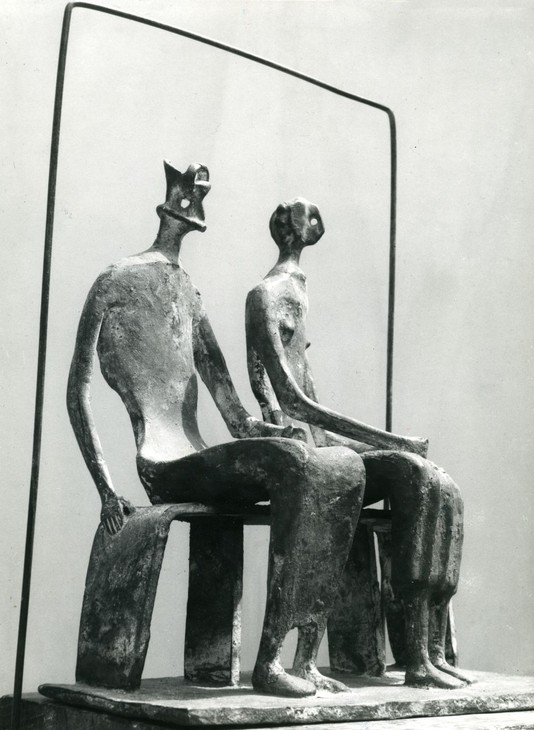

Henry Moore OM, CH,

King and Queen

1952-3, cast 1957

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Moore suggested that the idea for King and Queen came from ancient Egyptian statuary and from fairytales he read to his daughter. Others have suggested that it might have been related to a photograph of him and his wife Irina or that it could have been inspired by the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II that year. Although some critics disliked the sculpture’s unusual combination of naturalism and fantasy, King and Queen became one of Moore’s most famous works.

Henry Moore OM, CH 1898–1986

King and Queen

1952–3, cast 1957

Bronze

1635 x 1385 x 845 mm

Purchased from the artist by the Friends of the Tate Gallery with funds provided by Associated Rediffusion Ltd 1959

Number 5 in an edition of 5 plus 2 artist’s copies

T00228

King and Queen

1952–3, cast 1957

Bronze

1635 x 1385 x 845 mm

Purchased from the artist by the Friends of the Tate Gallery with funds provided by Associated Rediffusion Ltd 1959

Number 5 in an edition of 5 plus 2 artist’s copies

T00228

Ownership history

Purchased from the artist by the Friends of the Tate Gallery with funds provided by Associated Rediffusion Ltd 1959.

Exhibition history

1968–9

?Henry Moore, touring exhibition, Städtische Kunsthalle, Düsseldorf; Kunsthalle Bielefeld, Bielefeld; Staatliche Kunsthalle, Baden-Baden; Städtische Kunstsammlungen, Nuremberg, 1968–9.

1973

Henry Moore to Gilbert & George: Modern British Art from the Tate Gallery, Palais des Beaux-Arts, Brussels, September–November 1973, no.40.

1978

The Henry Moore Gift, Tate Gallery, London, June–August 1978, no number.

1981

Henry Moore: Sculptures, Drawings, Graphics 1921–1981, Palacio de Velázquez, Palacio de Cristal, Parque de El Retiro, Madrid, May–August 1981, no.7.

1981

Henry Moore, Fundacao Calouste Gulbenkian, Lisbon, September–November 1981, no.13.

1981–2

Henry Moore: Exposició Retrospectiva, Escultures, dibuixos i gravats 1921–1981, Fundació Joan Miró, Barcelona, December 1981–January 1982, no.13.

1983

Henry Moore: 60 Years of his Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, May–September 1983, no number.

1986

40 Years of Modern Art: 1945–1985, Tate Gallery, London, February–April 1986, no number.

1988

Henry Moore, Royal Academy of Arts, London, September–December 1988, no.126.

1998

A Sense of Form – Henry Moore at the British Museum: A Centenary Tribute, British Museum, London, May–September 1998.

2001

Henry Moore: Sculpting the 20th Century, Dallas Museum of Art, Dallas, February–May 2001; Legion of Honor, San Francisco, June–September 2001; National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C., October 2001–January 2002, no.61.

2005

Tate Sculpture: The Human Figure in British Art from Moore to Gormley, Millennium Galleries, Sheffield, January–April 2005.

2005

Henry Moore y México, Museo Dolores Olmedo, Mexico City, June–October 2005, no.39.

2006–07

Henry Moore: War and Utility, Imperial War Museum, London, September 2006–February 2007, no.19.

References

1953

Deuxième Biennale de la Sculpture, exhibition catalogue, Middelheim Park, Antwerp 1953 (another cast reproduced pp.26–7).

1954

New Bronzes by Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Leicester Galleries, London 1954 (another cast reproduced).

1954

Robert Melville, ‘Henry Moore and the Siting of Public Sculpture’, Architectural Review, February 1954 (another cast reproduced pp.87–95).

1954

David Sylvester, ‘Henry Moore’s Sculpture’, Britain Today, no.215, March 1954, pp.32–5.

1954

Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Curt Valentin, New York 1954 (another cast reproduced on front cover).

1957

Peter Anselm Riedl, Henry Moore: König und Königin, Stuttgart 1957 (another cast reproduced pls.1–10).

1958

Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Hatton Gallery, Newcastle 1958 (another cast reproduced).

1958

J.P. Hodin, Henry Moore, London 1958 (another cast reproduced pl.21).

1959

Erich Neumann, The Archetypal World of Henry Moore, London 1959, pp.112–15 (another cast reproduced pls.85, 87–8, 90).

1960

Will Grohmann, The Art of Henry Moore, London 1960, pp.147–8 (plaster original and another cast reproduced pls.133–6).

1960

Henry Moore: An Exhibition of Sculpture from 1950–1960, exhibition catalogue, Whitechapel Art Gallery, London 1960 (another cast reproduced, no.9).

1965

Alan Bowness (ed.), Henry Moore. Volume 2: Sculpture and Drawings 1949–1955, 1955, 2nd edn, London 1965, no.350 (another cast reproduced frontispiece and pls.80, 80a–i).

1965

Herbert Read, Henry Moore: A Study of his Life and Work, London 1965, pp.189–94 (another cast reproduced pls.176–7).

1966

Donald Hall, Henry Moore: The Life and Work of a Great Sculptor, London 1966, pp.129–31 (another cast reproduced p.130).

1968

John Hedgecoe (ed.), Henry Moore, London 1968, p.221 (plaster original and another cast reproduced pp.217–20, 222–3).

1968

Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Rijksmuseum Kröller-Müller, Otterlo 1968, reproduced.

1969

Henry Moore Exhibition in Japan, 1969, exhibition catalogue, National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo 1969, reproduced.

1970

Robert Melville, Henry Moore: Sculpture and Drawings 1921–1969, London 1970, pp.24, 211, reproduced pls.450–1, 454.

1972

Mostra di Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Forte di Belvedere, Florence 1972, reproduced p.154.

1973

John Russell, Henry Moore, London 1973 (another cast reproduced pl.63).

1973

Henry Moore to Gilbert & George: Modern British Art from the Tate Gallery, exhibition catalogue, Palais des Beaux-Arts, Brussels 1973, reproduced p.53.

1976

The Work of the British Sculptor Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Zürcher Forum, Zürich 1976, reproduced pp.108–9.

1977

David Finn, Henry Moore: Sculpture and Environment, London 1977 (another cast reproduced on dustjacket and pp.184–9, 298–305).

1978

The Henry Moore Gift, exhibition catalogue, Tate Gallery, London 1978, reproduced.

1978

Stephen Spender, Henry Moore: Sculptures in Landscape, London 1978, p.26.

1978

80/80: To Celebrate Henry Moore’s 80th Birthday on 30 July 1978, exhibition catalogue, Thomas Gibson Fine Art, London 1978 (another cast reproduced p.25).

1979

John Read, Portrait of an Artist: Henry Moore, London 1979 (another cast reproduced pp.110–2).

1981

Henry Moore: Sculptures, Drawings, Graphics 1921–1981, exhibition catalogue, Palacio de Velázquez, Madrid 1981, reproduced p.122, pls.245–7.

1983

William S. Lieberman, Henry Moore: 60 Years of his Art, exhibition catalogue, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York 1983, reproduced pp.72–3.

1983

Laurie Schneider, ‘A Note on the Iconography of Henry Moore’s “King and Queen”’, Source: Notes in the History of Art, vol.2, no.4, Summer 1983, pp.29–32.

1987

Henry Moore and Landscape, exhibition catalogue, Yorkshire Sculpture Park, West Bretton 1987 (another cast reproduced p.17).

1988

Susan Compton (ed.), Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Royal Academy of Arts, London 1988, reproduced no.126.

1989

Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Fondation Pierre Gianadda, Martigny 1989 (another cast reproduced pp.172–4 and on front cover).

1991

Henry Moore: The Human Dimension, exhibition catalogue, Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow 1991 (another cast reproduced pp.96–7).

1992

Henry Moore 1898–1986, exhibition catalogue, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney 1992 (another cast reproduced p.126).

1994

Laurie Schneider Adams, Art and Psychoanalysis, New York 1994 (?another cast reproduced p.78).

1996

Julie Summers, ‘Fragment of Maquette for King and Queen’, in Claude Allemand-Cosneau, Manfred Fath and David Mitchinson (eds.), Henry Moore From the Inside Out: Plasters, Carvings and Drawings, Munich 1996, p.126.

1998

Henry Moore: Friendship and Influence, Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts, Norwich 1998 (another cast reproduced pp.12–13).

1998

A Sense of Form – Henry Moore at the British Museum: A Centenary Tribute, exhibition catalogue, British Museum, London 1998.

1999

Henry Moore: Sculptures and Drawings, exhibition catalogue, Museum van Hedendaagse Kunst, Antwerp 1999, reproduced p.28 and front cover.

2001

Dorothy Kosinski (ed.), Henry Moore: Sculpting the 20th Century, exhibition catalogue, Dallas Museum of Art, Dallas 2001, p.201, reproduced no.61.

2002

Henry Moore: Rétrospective, exhibition catalogue, Fondation Maeght, Saint-Paul 2002 (another cast reproduced pp.150–1).

2005

Henry Moore y México, exhibition catalogue, Museo Dolores Olmedo, Mexico City 2005, reproduced p.69.

2006

Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Fundació ‘la Caixa’, Barcelona 2006 (another cast reproduced p.141).

2006

David Mitchinson (ed.), Celebrating Moore: Works from the Collection of the Henry Moore Foundation, London 2006 (another cast reproduced pp.239–42).

2006

Henry Moore: War and Utility, exhibition catalogue, Imperial War Museum, London 2006 (another cast reproduced p.48).

2007

Jeremy Lewison, Henry Moore 1898–1986, Cologne 2007 (another cast reproduced p.54).

2008

Christa Lichtenstern, Henry Moore: Work-Theory-Impact, London 2008 (another cast reproduced pp.193–4).

2011

Anita Feldman and Malcolm Woodward, Henry Moore: Plasters, London 2011, pp.66–71 (original plaster reproduced nos.71–2).

2013

Richard Calvocoressi, Martin Harrison and Francis Warner, Bacon / Moore: Flesh and Bone, exhibition catalogue, Ashmolean Museum, Oxford 2013 (another cast reproduced).

Technique and condition

This is a large bronze sculpture depicting two life-sized figures, one male and one female, seated side by side on a bench. The sculpture is fixed to a large rectangular bronze base by two bolts fitted from the underside of the base.

The high level of detail on the surface of the figures suggests that they were cast using the lost wax technique, whereas the more granular texture of the bronze on the base suggests a sand cast. Looking at the underneath of the sculpture it is still possible to see sand residues from this process.

To cast the sculpture in bronze a mould would have been taken from a full size model that Moore would have made in plaster. When working on a sculpture of this size he would first have built a supporting internal armature, probably using a combination of metal and wood, over which he applied wet plaster in successive layers to slowly build up the form. Moore used sharp tools and spatulas to produce a range of delicate striations in the plaster that have been reproduced in the bronze surface. A different effect is visible on the back of the queen’s head where a cross-hatched texture may indicate the use of scrim in the original model (fig.1). Eyelashes are suggested by linear inscriptions around the queen’s left eye, which is denoted by a circular hole (fig.2).

Detail of the back of the Queen's head, King and Queen 1952–3, cast 1957

Tate T00228

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.1

Detail of the back of the Queen's head, King and Queen 1952–3, cast 1957

Tate T00228

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Detail of Queen's head, King and Queen 1952–3, cast 1957

Tate T00228

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.2

Detail of Queen's head, King and Queen 1952–3, cast 1957

Tate T00228

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

When the plaster model was complete a mould made in a refractory material would have been taken from it in which to cast the sculpture in bronze. Large figures such as these would have been cast in pieces and then welded together at the foundry. Each weld has been filed down carefully and then textured with a series of special punches so that it blends with the surrounding surface, a process called chasing. The figures are hollow and are fixed to the bench seat with bolts. These fixings point up from the hollow interior of the bench and into the seated figures. Circular holes were drilled into the underside of the bench so that the bolts could be fixed. These holes were then filled in so that now only very faint circular marks remain to show where they were.

The surface of the bronze was cleaned after casting but there is no evidence of other post-casting finishing. The golden finish of a freshly cast bronze is normally coloured artificially by applying chemical solutions to the metal, either with or without heat, which react with the surface to produce various coloured compounds. This sculpture has an even, slightly transparent brown patina that can be produced using a chemical like potassium polysulphide. This is initially applied with a brush and then worked into the surface until the desired colour is reached. The sculpture would then have been given a coating of wax to protect it. There is no signature or foundry mark visible.

Lyndsey Morgan

November 2012

How to cite

Lyndsey Morgan, 'Technique and Condition', November 2012, in Alice Correia, ‘King and Queen 1952–3, cast 1957 by Henry Moore OM, CH’, catalogue entry, December 2013, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015, https://wwwEntry

King and Queen comprises a male and a female figure sitting side by side on a bench. The male figure is slightly broader and taller than the female and when viewed from the front it is evident that they are both sitting at an angle, facing left of centre. The female figure sits further forward on the bench in a more upright position, while the male figure appears to be leaning back slightly, as though more relaxed.

The head of the male is delineated by an angular lower jaw that narrows to a sharp point at the chin and a thin blade of bronze occupying the position of the nose that connects the chin to the top of the head in a straight line (fig.1). In the place of cheeks are hollowed cavities that accentuate the sharpness of the central ridge, through which a circular hole has been drilled to denote expressionless eyes. The top of the head is flat but slopes steeply upwards from the front to the back. At the front, above the central nasal ridge, is a semi-circular band that extends out of the mass of the head and arches up and over to the other side of the face, and may signify a quiff of hair or an ornamental headpiece (fig.2). From some angles it appears as though the upper rear edges of the head take the form of goat-like horns. The thinness of the face contrasts with the two rounded protrusions at the nape of the neck.

Detail of heads of King and Queen 1952–3, cast 1957

Tate T00228

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.1

Detail of heads of King and Queen 1952–3, cast 1957

Tate T00228

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Detail of King's head, King and Queen 1952–3, cast 1957

Tate T00228

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.2

Detail of King's head, King and Queen 1952–3, cast 1957

Tate T00228

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

The male figure’s shoulders are symmetrical and follow the line of an arc; the collar-bone and chest repeat the curve of the shoulders, and no bodily features such as nipples, muscles or a navel are visible on the torso suggesting that the figure is clothed. The arms are thin tubular limbs; the left arm is held slightly in front of the body and is bent at the elbow so that the left hand, with individually modelled fingers, rests in the figure’s lap (fig.3). The right arm is positioned slightly behind the body, with a slight crook in the elbow. The forearm tapers to a narrow wrist and the palm of the right hand rests flat on the side leg of the bench (fig.4).

Detail of King's left hand, King and Queen 1952–3, cast 1957

Tate T00228

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.3

Detail of King's left hand, King and Queen 1952–3, cast 1957

Tate T00228

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Detail of King's right hand, King and Queen 1952–3, cast 1957

Tate T00228

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.4

Detail of King's right hand, King and Queen 1952–3, cast 1957

Tate T00228

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Seen from the side and the rear it is evident that the body is very thin, and there is a recessed, concave space between the shoulder blades that extends down the spine to the waist, which is narrow and serves to emphasise the figure’s broad shoulders. The figure is curved at the hips, and the legs extend horizontally off the bench, bending at the knees. The lower half of a tunic binds the two legs together and ends three-quarters of the way down the figure’s calves. Three pleats or folds of fabric can be seen running down the front of the tunic in between the figure’s legs, which lead to naturalistically modelled human ankles and feet placed firmly on the flat bronze base.

The female figure sits to the left of the male figure, with a gap between them. Her head combines a thin, fin-like face with rounder forms at the rear. The central facial ridge consists of two angles that originate from the forehead and chin respectively, and meet at a point in the middle that could be identified as a nose. A circular hole pierces the thin face just like that of the male’s and denotes the eyes. Eyelashes have been incised on the left side of the face. The female also sports a semi-circular band that extends out and over the top of her head and could be deemed to represent a diadem (fig.5). Three bulbous forms are positioned at the nape of the figure’s neck and resemble bunches of pinned up hair.

The female’s body is akin to the male’s: it is long, thin and ribbon like, curved at the hips and knees and sits firmly on the bench. Overall she is smaller than her male counterpart, but the most conspicuous differences between them are the small, widely spaced, domed breasts on the female figure’s chest and her slightly wider hips. Her thin, elongated arms lead to her lap, where her hands interlock delicately (fig.6).

Like the male figure, the female figure is wearing a tunic. Her legs are undefined underneath the fabric but clearly extend over the edge of the bench and bend at the knees. The tunic ends two-thirds of the way down her calves where five pleats or folds can be counted. Each of the concave, vertical folds is separated by a convex curved ridge, which cumulatively create an undulating surface. The figure’s ankles appear from underneath the tunic and lead to feet planted firmly on the rectangular base (fig.7).

Although the two figures do not touch each other, and each one has been rendered individually, a sense of familiarity has been achieved by the ways in which their bodies replicate each other. Both have a similar spinal curve and concave spaces in their backs, and when seen from the front, the curve of their shoulders and the flatness of their torsos are similar. The shape and bend of the female’s right arm mirrors that of the male’s left. The surfaces of the two figures are highly marked, although not rough (fig.8). When seen from the rear, long vertical scratches run down the length of both figures’ backs and serve to emphasise the elongated proportions of the bodies.

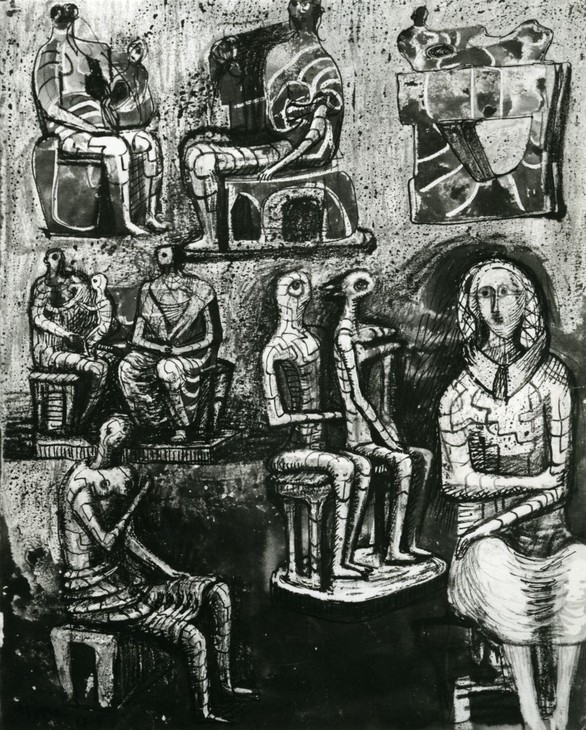

In the early 1950s Moore slowly began phasing out the practice of making preparatory drawings for each new sculptural project. Although he continued to make sketches on paper, these were records of general ideas and were rarely, if ever, translated into specific sculptures. This change in working practice was probably the result of a number of factors, but principally due to his turn to bronze casting. The inherently malleable qualities of wax, clay, and plaster from which a bronze could be cast meant that Moore was able to add as well as subtract forms as he worked, thus avoiding the necessity of having to plan the form of a sculpture on paper in advance, as is the case when carving in stone or wood. In addition to changing his materials and techniques, by the early 1950s Moore had amassed a large collection of graphic designs for sculptures that he had drawn in the 1940s, to which he was able to refer at a later date.

Henry Moore

Seated Figures c.1948

Pencil, wax crayon, coloured crayon, watercolour wash, pen and ink, and gouache on off-white medium –wove paper

Tate T00228

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.9

Henry Moore

Seated Figures c.1948

Tate T00228

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

The ‘King and Queen’ is rather strange. Like many of my sculptures, I can’t explain exactly how it evolved. Anything can start me off on a sculpture idea, and in this case it was playing with a small piece of modelling wax ... Whilst manipulating a piece of this wax, it began to look like a horned, Pan-like, bearded head. Then it grew a crown and I recognised it immediately as the head of a king. I continued and gave it a body.2

If Moore’s recollection was correct, and the horned or beak-like head developed while he was modeling in wax, then a drawing of King and Queen made in c.1952 (fig.10) depicting the King with these features must have been completed after he made the initial maquette. A description of the creation of King and Queen provided by Moore’s biographer Donald Hall supports Moore’s recollection and goes into more detail:

The King’s head was the first thing that happened. Moore was idly fingering a piece of wax, with no idea of making such an image. He pinched the wax between thumb and forefinger, and the result made him think of the god Pan – or of a king. In a few minutes he virtually completed the head. Later the same day he made the King’s body. He dropped a flat sheet of wax in a pan of water to soften it, and cut it with a knife, and bent and rolled it to its proper thin shape. The idea of the couple crystallized overnight ... The next day he made the bench and a Queen to sit on it, space between her and the King. He added a thin wire-like frame, squaring the couple on all sides and the maquette was finished.3

However, in 2006 the sculptor Anthony Caro, who worked as one of Moore’s studio assistants between 1951 and 1953, described slightly differently how the wax maquette was made:

I remember watching Henry making the King and Queen maquette. The way he worked in wax intrigued me. He got attracted to working in wax while I was there. He set up a situation whereby we all partook in parts of his process. Alan Ingham [another studio assistant] and I were helping him in the big studio, the old cow shed ... First we boiled up the wax and poured it out on to flat sheets, so he’d got wax roughly the thickness of a casting. Then he’d cut it out, he’d cut out the shape of the figure he wanted – in this case the bodies of the King and Queen – and he did it exactly like a tailor cutting cloth into shape. He worked on a very small scale, the whole figure about six or eight inches [15–20 cm] high. He’d get this little figure and bend the warm wax into a seated position, then he’d make a little wax seat for it and give it legs and arms made up of thin elements of wax which he’d model. He was good at modelling hands or feet on a tiny scale. When it came to the head he’d make the head out of small wax parts, weld them together and dip the whole head into hot water, so the shapes would melt a little and cohere and the parts of the head would run together.4

Although there are slight differences between these three accounts, taken together they nonetheless provide a vivid description of the ways in which Moore experimented with forms by modelling in wax.

Henry Moore

Maquette for King and Queen 1952

Bronze

Private collection

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.11

Henry Moore

Maquette for King and Queen 1952

Private collection

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Having made the wax version, and possibly before casting the bronze, Moore also made a copy of the sculpture in plaster. A fragment of the queen’s head, torso and arms is held in the collection of the Henry Moore Foundation (fig.12). In this work, the plaster of the arms has been built over a wire armature. Since Hall suggested that the bronze cast was made using the original wax, it is unlikely that this plaster was created for casting purposes. However, its later role as a template for the creation of an enlarged version can be identified by the presence of numbers and crosses marked in pencil on the surface of the plaster.

Henry Moore

Maquette for King and Queen 1952–3

Plaster with surface colour

230 mm

Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.13

Henry Moore

Maquette for King and Queen 1952–3

Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

I enlarged the Queen in terracotta for Henry. When I had been at the Royal Academy of Art Siegfried Charoux and Arnold Machin had taught me the technique of working in terracotta. I said to Henry, ‘Would you like me to enlarge it to three-quarters size in terracotta?’ and he said, ‘Yes, good idea, go ahead’. I don’t know why we never did the King, as he was pleased with the Queen. It was slow working in terracotta: you have to wait for the clay to harden and dry to a leathery consistency before you can go on to the next stage. Again, he would do a bit with it, he would push it here and there in the thorax for example, but by and large he mostly worked on the hands, feet and head.8

Henry Moore

Seated Figure 1952–3

Terracotta

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.14

Henry Moore

Seated Figure 1952–3

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

In a letter written to the American lawyer and philanthropist Allan D. Emil on 21 October 1966 Moore responded to a query about his sculpture Hand Relief No.1 1952:

You are quite right in thinking it is the study for the hands on a larger work, actually of the KING AND QUEEN, 1952/53.

When I was making the large version of the KING AND QUEEN, and getting to working on the hands in detail, I got a little stuck with them, and contrary to any previous practice, I felt I needed to have a model of a real hand. And so I asked my wife to come into the studio and hold her hand in the position I required – she posed for about a quarter of an hour and then said she couldn’t stay any longer as the lunch she was cooking needed her attention. I then asked Mary, my daughter who was six years old, to come and hold her hand in the position I wanted, and in this way I was helped in completing the hands of the full-size sculpture.11

When I was making the large version of the KING AND QUEEN, and getting to working on the hands in detail, I got a little stuck with them, and contrary to any previous practice, I felt I needed to have a model of a real hand. And so I asked my wife to come into the studio and hold her hand in the position I required – she posed for about a quarter of an hour and then said she couldn’t stay any longer as the lunch she was cooking needed her attention. I then asked Mary, my daughter who was six years old, to come and hold her hand in the position I wanted, and in this way I was helped in completing the hands of the full-size sculpture.11

In addition to using his wife and daughter as models, the scholar Alan Wilkinson has noted that ‘Tam Miller, Moore’s secretary from 1950 to 1956, also recalls standing in Moore’s studio for two hours at a time with her hands on a little platform at elbow height’.12 Similarly, the curator David Mitchinson has recorded that Moore’s studio assistant Alan Ingham also modelled for the feet of the King.13 The remodelled Hands of Queen were cast separately and exist as distinct sculptures in their own right.

Full-size plaster of King and Queen 1952–3 in the garden at Hoglands

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.15

Full-size plaster of King and Queen 1952–3 in the garden at Hoglands

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Moore made several different versions of the Queen’s head. In 1968 Moore recalled that ‘the head of the Queen was a problem because it had to be in harmony and I made two or three different attempts at it before being satisfied’.14 Since the head of the King was so distinctive it was important that the Queen’s head reflected the regality of her counterpart and thus convey a sense of unity, but also projected an identity of its own. Study for Head of Queen No.2 1952–3 (fig.16) appears to be similar to the head of the bronze maquette, while Study for Head of Queen 1952–3 (fig.17) is more naturalistic, with a clearly recognisable crown. The nature of plaster is such that Moore would have been able to remove the heads and limbs of the figures and replace them with alternatives. Although it does not appear to show either of the surviving designs, a photograph of the full size plaster taken inside Moore’s studio records the Queen with a different head to that of the final bronze. A seam running around the circumference of the Queen’s neck indicates where the head has been attached and it is notable that in this photograph the head of the Queen is looking towards the King (fig.18). However, Moore clearly found the Queen’s head and its orientation unsatisfactory because he reworked the design to present the face in a thin, fin-like form, like the King’s, and replicated his curved crown.

Henry Moore

Study for Head of Queen No.2 1952–3

Plaster

245 x 180 x 220 mm

Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.16

Henry Moore

Study for Head of Queen No.2 1952–3

Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore

Study for Head of Queen 1952–3

220 x 190 x 210 mm

Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.17

Henry Moore

Study for Head of Queen 1952–3

Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

When the plaster was finished it was placed outside in his garden. Given the cramped conditions of Moore’s studio it is likely that Moore placed the sculpture outside so that he could look at it from a distance without other works blocking his view. At this time Moore experimented with the inclusion of the thin rectangular frame, as found in the original maquette. However, he ultimately decided against including this frame in the final version. When asked why he had omitted it Moore reportedly told Alan Wilkinson that, ‘oh, on a larger scale, they would look as if they were keeping goal in a soccer match’.15

Full-size plaster of King and Queen 1952–3 in Moore's studio with an alternative queen's head

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.18

Full-size plaster of King and Queen 1952–3 in Moore's studio with an alternative queen's head

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

The full-size plaster was completed in early 1953 and sent to the foundry for casting. Moore employed the Art Bronze Foundry in London to cast the first bronze example of King and Queen. He had previously commissioned this foundry to cast his maquettes for Madonna and Child in 1943 (Tate N05600–N05603) and he continued to use their services throughout the 1950s. It is likely that Moore first came into contact with the foundry when he was Head of the Sculpture Department at Chelsea College of Art in the 1930s; the foundry was located close to the College and was regularly used by staff and students. At the foundry, the technicians would use the plaster to create a hollow mould, into which molten bronze could be poured. King and Queen was originally cast in an edition of four, plus one artist’s copy. The fifth cast, which is now owned by Tate, was made in 1957. A second artist’s cast was made in 1985 and is now in the collection of the Henry Moore Foundation.

After casting at the foundry the bronze sculptures were returned to Moore so that he could check the quality of the casting and make decisions about the patination. A patina is the surface colour of a sculpture and is usually achieved by applying chemical solutions to the pre-heated bronze sculpture. In 1960 Moore explained:

I like working on all my bronzes after they come back from the foundry. A new cast to begin with is just like a new-minted penny, with a kind of slight tarnished effect on it. Sometimes this is right and suitable for a sculpture, but not always. Bronze is very sensitive to chemicals, and bronze naturally in the open air (particularly near the sea) will turn with time and the action of the atmosphere to a beautiful green. But sometimes one can’t wait for nature to have its go at the bronze, and you can speed it up by treating the bronze with different acids which will produce different effects. Some will turn the bronze black, others will turn it green, others will turn it red.16

Moore went on to explain that when working on his plasters he normally had a preconceived idea of what colour the sculpture would eventually take. However, he acknowledged that working with chemical patinas was not easy, and that it was difficult to replicate the same colours and effects across the edition.17 Tate’s King and Queen has a fairly consistent brown patina, although the surface of some high points, such as the Queen’s shoulders, has been worked to produce a golden-brown finish. Moore explained in 1960 that after patination ‘you can then work on the bronze, work on the surface and let the bronze come through again, after you’ve made certain patinas. You rub it and wear it down as you hand might by a lot of handling. From this point of view bronze is the most responsive and unbelievably varied material’.18 In contrast to Tate’s cast, the King and Queen in the collection of the Henry Moore Foundation, which is displayed outside, has turned a mottled sea-green, just as Moore predicted.

King and Queen is Moore’s only sculpture depicting solely a pair of adult figures. Although Moore said that he recognised the male head to be that of a king as soon as he made it, according to the curator David Mitchinson, ‘in one of Moore’s early sale record books this sculpture is rather prosaically called Two Seated Figures’.19 This title was occasionally used concurrently with King and Queen. For example, the sculpture was titled Two Seated Figures while on exhibition at the Musée Rodin in Paris in 1961 and when it was included in Moore’s exhibition at the Israel Museum in Jerusalem in 1966. Moore’s first statement on King and Queen was published in the exhibition catalogue for his solo show at Curt Valentin Gallery in New York in 1954:

The King and Queen group has nothing to do with present-day Kings and Queens but is more connected with the archaic or primitive idea of a King. The ‘clue’ to the group is perhaps the head of the King which is a head and a crown, face and beard combined into one form and in my mind has some slight Pan-like suggestion, almost animal, and yet, I think, something Kingly. How the group came about I don’t know, unless it may be that in the last year or two I have read stories to my daughter in which Kings and Queens have appeared a lot and this might have made one’s mind open to such a subject.20

The relation that Moore drew between the head of the King and Pan, the ancient Greek god of the wild, reinforces the sense that the figures in the sculpture represent archaic, ancient or otherworldly characters. Pan’s body was an amalgamation of animal and human form; he had the haunches of a goat and horns on his otherwise human head. Indeed, the art historian Will Grohmann has compared the King’s head with Goat’s Head 1952 (fig.19), which Moore made around the same time that he made King and Queen. Goat’s Head has a long thin snout, a pointed nose and horns that resemble the thin, elongated shape of the King’s head, beard and crown.

Limestone statue of a husband and wife c.1300 BC

British Museum, London

© Trustees of The British Museum

Fig.20

Limestone statue of a husband and wife c.1300 BC

British Museum, London

© Trustees of The British Museum

This has always been a great favourite of mine. For me these two people are terribly real and I feel the difference between male and female. The sculptor had done it in an obvious way by making the man slightly bigger than the woman, but it works, and this influenced me when I came to make my bronze King and Queen. It is such a pity the hands are damaged for, after the face, I think the hands are the most expressive part of the body. But even damaged the arms have a superb sense of repose and serenity which is so characteristic of Egyptian sculpture. Notice too that there are no marks of aging on the faces. The pair are represented at an ideal age, one of full growth but before disillusionment has set in.23

Henry Moore with the ancient Egyptian statue of a husband and wife in the British Museum, 1980–1

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: David Finn, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.21

Henry Moore with the ancient Egyptian statue of a husband and wife in the British Museum, 1980–1

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: David Finn, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

It was a big subject, the King and Queen. When I was working on them, I was reminded of an Egyptian sculpture in the British Museum that I had seen many times of a seated figure of an official and his wife. But somehow the sculptor had raised them above this status and had given them greater dignity and self-assurance, almost a nobility of purpose to make them appear above normal life. I’ve tried to inflect some of this feeling into my sculpture.25

Moreover, in 1998 Tate lent King and Queen to the British Museum where it was displayed opposite the Egyptian sculpture, as if the two couples were in conversation.

However, as early as 1960 Grohmann questioned the extent to which Moore’s King and Queen could be regarded as a modern counterpart to the Egyptian sculpture in the British Museum. Grohmann suggested that ‘to see references to Egyptian royal groups, such as the 18th-dynasty group in the British Museum, is incorrect; Moore could only have learnt from them what he did not want to do’.26 He went on to explain that unlike the ancient Egyptian couple, ‘there is nothing imperious about this royal pair; on the contrary, it is a very human couple’.27

Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh. Coronation portrait, June 1953, London, England

Photo: Cecil Beaton

Fig.22

Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh. Coronation portrait, June 1953, London, England

Photo: Cecil Beaton

Henry and Irina Moore c.1952

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Jitendra Arya, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.23

Henry and Irina Moore c.1952

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Jitendra Arya, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

The earliest cast of King and Queen was first exhibited at the Second Biennial for Sculpture at Middelheim Park in Antwerp in the summer of 1953. It was bought by the city of Antwerp and is now part of the permanent collection of the Middelheim Sculpture Park. Another cast was exhibited in London at the Leicester Galleries in February 1954. At this time, critical responses to the work focused on the form the sculpture took and the combination of abstract and figurative styles, which were unusual to find together in a single sculpture. Writing in the Observer, critic Nigel Gosling suggested that ‘the mingling of naturalistic limbs with only semi-representational heads is a surrealist gambit’, which he suggested was ‘disturbing’.31 In a review titled ‘Mr Moore’s New Bronzes: An Experimental Phase’, the unnamed critic writing for the Times suggested that the works in the exhibition, including King and Queen, ‘are prone to inconsistencies of style, which in spite of their many passages of subtle observation, give them the air of experiments which have yet to be resolved’.32 On a more positive note, Stephen Bone writing in the Guardian noted that Moore’s ‘strange inconsistencies’ in King and Queen were ‘plainly deliberate and carefully considered’, concluding that ‘the result is far more successful than might have been expected, though a faintly uneasy air of experiment hangs about this group’.33

Perhaps the most significant – but scathing – review of King and Queen was written by the critic David Sylvester and published in the journal Britain Today in March 1954. Sylvester had curated Moore’s 1951 exhibition at the Tate Gallery and was a close friend and collaborator. Although he started his review by noting the dichotomy of Moore’s recent work, which veered from the figurative Draped Reclining Figure 1952–3 (Henry Moore Foundation) to the geometric arrangements of the Time Life Screen 1952–3 (Time Life Building, London), when considering the union of abstract and naturalistic forms in King and Queen Sylvester proclaimed that ‘I, for my part, do not find these deliberate inconsistencies acceptable. I would like to see the King’s head existing as a work in its own right. Still more I would like to see the exquisitely modeled and proportioned feet and hands attached to bodies of an equally serene beauty’.34 Sylvester concluded stating, ‘Moore’s recent major works suggest that at present his aesthetic personality is a split one’.35 With these remarks in mind, it is telling why Sylvester chose not to include King and Queen in the retrospective of Moore’s work that he curated at the Tate Gallery in 1968.

A year after Sylvester’s review was published Moore explained why he consolidated different representational forms in King and Queen: ‘some parts of it are more realistic than others – the hands and feet particularly – to bring out the contrast between human grace and the concept of power in primitive kingship’.36 He reiterated his position in 1957 during an interview with the critic J.P. Hodin:

After Surrealism nobody should be upset that a head of one of my sculptures is different from the rest. Could not we say the same of Chartres, or of many primitive works? In Chartres Cathedral, the bodies are like columns and the heads are realistic. No one reproaches them for disunity of style. I willingly accept what I try to bring together. In the heads of my “King and Queen” ... some mixture of degrees of realism is implicit. But we got used to this mixture in Chartres, and we shall get used to it again.37

For critic Peter Anselm Riedl, writing for a German audience in 1957, it was the strange disparity between various component parts of King and Queen that made the sculpture so powerful. Riedl described how ‘the two beings are both familiar and unfamiliar to us at the same time’.38 In a discussion of the figures’ heads he noted:

The two figures have eyes like those of an insect, somehow dangerous and yet somehow noncommittal. In fact, they are not eyes at all, just holes, channels, that make the heads see-through. But this just creates a strange spell-like effect. One feels haunted by an invisible gaze that is actually wandering elsewhere – into the distance, into the void.39

In 1966 Donald Hall narrated that, ‘the large version, he [Moore] says, allowed him to carry further the human implications of the King and Queen. Working over it, he felt that he could add meaning, or slant meaning, by how he made the hands. The King’s hand resting on his knee could be clenched like a dictator’s, or floppy like a weak king’s, or in between’.40

Moore always paid careful attention to the depiction of hands and in 1980 reflected that, ‘hands can convey so much – they can beg or refuse, take or give, be open or clenched, show content or anxiety. They can be young or old, beautiful or deformed ... throughout the history of sculpture and painting one can find that artists have shown through the hands the feelings they wished to represent’.41 Like the hands of his earlier carving Girl 1931 (Tate N06078), the hands of the Queen have not just been modelled sensitively but suggest a sensitivity of touch. The fingers are gently interlocked but do not appear to apply any pressure to the skin.

Despite the ambivalence of some critics when it was first exhibited, King and Queen quickly cemented itself as one of Moore’s best known sculptures. As early as 1954 the critic Robert Melville claimed that ‘it is Moore’s finest achievement since the war, and probably the most graceful of all his works’.42 For Melville the sculpture demonstrated a ‘resolution of conflict between a static, hieratic approach and a dynamic, humanist one’, marrying a sense of primal longevity with an alert awareness of the immediate moment.43 Melville discussed the figure using phrases such as ‘magic and terror’, and contrasted the two figures, suggesting that the presence of the graceful Queen ‘is a kind of guarantee that the King will not peck out the hearts of his subjects’.44 The otherworldliness of King and Queen was also noted by the critic Herbert Read. In his introduction to the second volume of Moore’s catalogue raisonné (first published in 1955), Read noted that although the sculpture could be linked to the earlier family groups, ‘there is an equally obvious break, and it is a break with humanism and an advance into the superhuman realm of myth. This king and queen never reigned in our world’.45 Similarly in 1957 Riedl suggested that the ceremonial rigidity of the figures and their aimless gazing removed them from the activities of the everyday world, and placed them in a realm ‘beyond “doing”’.46

By 1960 Grohmann praised King and Queen ‘as a highwater mark in Moore’s creative work, a monument – for that is what it is – timeless and without specific purpose’.47 He went on to note that ‘it quickly won public recognition and higher esteem than the more naturalistic Madonnas at Northampton and for St Peter’s Church in Claydon’.48 Suggesting that this public esteem was a result of the multiplicity of styles found in the work, Grohmann argued that in combining human, animal and non-representational forms, Moore’s sculpture embodied ‘the totality of the world, sculpturally speaking of the unity of natural and supernatural, objective and abstract. Thus there is a synthesis here too, synthesis in the combination of the archaic with the contemporary, the unconscious with the spiritual’.49

This interpretation of the sculpture as somehow archaic, magical and mysterious was supported by the widespread reproduction of photographs taken by Moore himself showing King and Queen positioned outside in the Scottish countryside (fig.24). This cast of the sculpture was bought by W.J. Keswick in 1954 and installed on his estate, Glenkiln, in Dumfriesshire. In 1960 Moore described how the work came to be placed outside:

When Mr Keswick invited me to stay with him, I went all over his land, and there are not only the wild hills and moors but woods and lawns, and a lake with an island in the middle. I saw at least twenty or thirty sites for the sculpture which are separated from one another by hillside or trees, so that one could never see more than one sculpture at a time. There was such a large variety that I feel that every large sculpture I have done could find a suitable setting there. He showed me a scar on one hillside – a kind of scooping out, that formed a natural dais. We thought that this would be the right spot for King and Queen, and here eventually the two figures were placed. They look across forty miles of countryside into England.50

The placement of this cast of King and Queen in an isolated landscape has shaped interpretations of the sculpture more generally. In his book The Archetypal World of Henry Moore (1959), the psychologist Erich Neumann described the couple as lonely and desolate, an interpretation that is supported by the inclusion of a photograph of the sculpture at Glenkiln in which the two figures appear isolated on a rocky bluff.51

King and Queen 1952–3 installed on the Keswick Estate, Glenkiln, Dumfriesshire, c.1954

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.24

King and Queen 1952–3 installed on the Keswick Estate, Glenkiln, Dumfriesshire, c.1954

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

According to the photographer David Finn, ‘Moore has always loved photographs showing the piece on the hills of Glenkiln’.52 Indeed, Moore kept a selection of photographs showing the work from a variety of viewpoints pinned to a notice board in his studio. Some of these photographs of King and Queen in situ in the Scottish landscape were reproduced in Moore’s catalogue raisonné published in 1955, and regularly featured in articles and books about the artist, including the monographs written by Herbert Read (1965), Donald Hall (1966), and John Russell (1973) among others. The experience of installing this work and other sculptures at Glenkiln encouraged Moore to place more of his work outside. In 1978 he reflected on the importance of the open sky as a backdrop for his work, and concluded that ‘sculpture – at any rate, my sculpture – is best seen in this way and not in a museum’.53 In the foreword written for David Finn’s book, Henry Moore: Sculpture and Environment (1977), the former director of the National Gallery, Kenneth Clark, wrote that ‘the supreme examples of siting Moore’s work are Tony Keswick’s placements of four pieces on his sheep farm at Glenkiln in Dumfriesshire, Scotland ... everyone who sees the works in this setting comes away deeply moved ... The siting of the Glenkiln pieces is what one might call a Wordsworthian use of sculpture’.54

In a talk given in 1955 about sculpture in the open air, Moore noted that he had already begun work on the idea for the piece before it had been selected for the Second Biennial for Sculpture at Middelheim Park in Antwerp, making the point that he felt free to sell the same work to other clients: ‘although this Group has been listed as a commission from the Burgomaster of Antwerp, the maquette had already been produced before Antwerp decided to have a piece of my sculpture for the open-air museum in Middelheim Park. It was simply a sculpture that I wanted to do’.55 The second cast was bought by W.J. Keswick in 1954 for the Keswick Estate at Glenkiln and the third cast was bought by Joseph H. Hirshhorn through the Curt Valentin gallery in New York and is now housed in the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden in Washington, D.C.. The fourth version cast in 1953 was bought for £3,000 by David Astor, a former editor of the Observer newspaper, from Moore’s 1954 Leicester Galleries exhibition. Astor displayed it in his garden in St John’s Wood, London, until 1976, when he sold it to the Norton Simon Museum of Art in Pasadena. The original artist’s copy was held in the collection of the artist’s daughter but is now in the collection of the Moa Museum of Art in Atami, Japan.

On 16 May 1957 the Director of the Tate Gallery, John Rothenstein, met with the Board of Trustees to discuss proposals to expand the gallery’s holdings of works by Henry Moore. Rothenstein explained that Moore had suggested that the gallery purchase eight sculptures representing the different phases of his work since the early 1930s. By this time the four original casts of King and Queen had already been sold, but it was suggested that an additional cast could be made especially for Tate should the gallery wish to acquire it. Although the trustees decided not to purchase all of the suggested sculptures immediately, they did agree to the acquisition of King and Queen. According to the minutes of the meeting, ‘the Director emphasised the extreme generosity and helpfulness of the sculptor’s attitude in making works available from his own collection for sums substantially below their market value ... and for agreeing to seek the approval of the authorities of the City of Antwerp for making an extra cast of King and Queen’.56 The owners of the first four casts had bought the sculpture on the understanding that no other casts would be made, and might have complained that a fifth example would diminish the value of their pieces. Moore therefore was obliged to seek their approval for this idea. In fact, the owners readily agreed as this additional cast would not enter the commercial market and would be acquired directly by the Tate Gallery. By 3 June 1957 Moore was able to write to Rothenstein to say ‘I am straight away fixing with the foundry for the casting of the King and Queen’.57

The casting and patination of Tate’s cast, however, took well over a year. In a letter to Moore dated 18 July 1958 Rothenstein noted the he had informed the trustees of the artist’s generosity in lowering the price to ‘virtually the cost of the casting, namely £1,200’.58 The purchase was also made possible due to ‘funds made available by Associated Rediffusion’, the first independent commercial television broadcaster in the London region, formed following the 1954 Independent Television Act of Parliament, which broke the BBC’s monopoly over television broadcasting. 59

In November 1958 the Deputy Director, Norman Reid, wrote to Moore asking whether King and Queen would be available for viewing at the meeting of the Friends of the Tate, which was due to take place on 4 December. Reid enquired, ‘Are you ready to part with it yet or do you think it should stay longer with you for the sake of the patina?’60 Moore evidently felt that the sculpture should remain in his possession for a little while longer because it was not until late January that arrangements were made for the transportation of King and Queen from Moore’s studio in Perry Green to the Tate. The sculpture was first exhibited at the gallery on 4 February 1959.

Alice Correia

December 2013

Notes

Another drawing by Moore dating from 1949 depicting a male and female couple sitting on a low bench was reproduced in Alan Bowness (ed.), Henry Moore. Volume 2: Sculpture and Drawings 1949–1955, 1955, 2nd edn, London 1965, pl.96.

Anthony Caro, ‘King and Queen 1952–53’, in David Mitchinson (ed.), Celebrating Moore: Works from the Collection of the Henry Moore Foundation, London 2006, p.241.

Julie Summers, ‘Fragment of Maquette for King and Queen’, in Claude Allemand-Cosneau, Manfred Fath and David Mitchinson (eds.), Henry Moore From the Inside Out: Plasters, Carvings and Drawings, Munich 1996, p.126.

Henry Moore, letter to Allan D. Emil, 21 October 1966, reprinted in Alan Wilkinson (ed.), Henry Moore: Writings and Conversations, Aldershot 2002, p.283. This letter is held in the Archives of American Art, Washington, D.C. See http://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/allan-d-and-kate-s-emil-papers-8502 , accessed 29 January 2014.

David Mitchinson, ‘King and Queen’, in Henry Moore: War and Utility, exhibition catalogue, Imperial War Museum, London 2006, p.48.

Alan G. Wilkinson, Henry Moore Remembered: The Collection at the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto, Toronto 1987, p.140.

As Moore’s biographer Donald Hall recalled: ‘An Egyptian Limestone Seated Figure is the sculpture Moore remembers especially. The official and his wife are rocky and solid.’ Hall 1966, pp.129–30.

In his introduction to the book Moore concluded that ‘It has been a wonderful experience for me to recapture the delight, the excitement, the inspiration I got in these pieces as a young and developing sculptor’. Henry Moore, Henry Moore at the British Museum, London 1981, p.16.

Anita Feldman Bennet, ‘Rediscovering Humanism’, in Henry Moore: In the Light of Greece, exhibition catalogue, Basil and Elise Goulandris Foundation Museum of Contemporary Art, Andros 2000, p.65. A copy of this portrait, which was taken by the photographer Jitendra Arya around 1952, is held in the Henry Moore Foundation Archive, although it is uncertain when the image came into Moore’s possession.

Henry Moore, ‘Sculpture in the Open Air: A Talk by Henry Moore on his Sculpture and its Placing in Open-Air Sites’, March 1955, p.7, Tate Artist Catalogue File, Henry Moore, A23941.

Robert Melville, ‘Henry Moore and the Siting of Public Sculpture’, Architectural Review, February 1954, pp.88–9.

Herbert Read, ‘Introduction’, in Alan Bowness (ed.), Henry Moore. Volume 2: Sculpture and Drawings 1949–1955, 1955, 2nd edn, London 1965, p.x.

Henry Moore cited in ‘Sculpture in Landscape’, Selection, Autumn 1962, pp.12, 15, reprinted in Wilkinson 2002, p.246.

Minutes of a Meeting of the Trustees of the Tate Gallery, 16 May 1957, Tate Public Records TG 4/2/742/2.

Related essays

- Fashioning a Post-War Reputation: Henry Moore as a Civic Sculptor c.1943–58 Andrew Stephenson

- Henry Moore: The Plasters Anita Feldman

- Henry Moore and the Welfare State Dawn Pereira

- Henry Moore and World Sculpture Dawn Ades

- Henry Moore's Approach to Bronze Lyndsey Morgan and Rozemarijn van der Molen

- Biography Alice Correia

Related material

Related reviews and articles

- Henry Moore, ‘The Sculptor in Modern Society’ Unesco, International Conference of Artists, Venice 1952.

How to cite

Alice Correia, ‘King and Queen 1952–3, cast 1957 by Henry Moore OM, CH’, catalogue entry, December 2013, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015, https://www