Henry Moore OM, CH Maquette for Fallen Warrior 1956, cast 1956-7

Image 1 of 10

-

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Fallen Warrior 1956, cast 1956-7© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Fallen Warrior 1956, cast 1956-7© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Fallen Warrior 1956, cast 1956-7© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Fallen Warrior 1956, cast 1956-7© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Fallen Warrior 1956, cast 1956-7© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Fallen Warrior 1956, cast 1956-7© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Fallen Warrior 1956, cast 1956-7© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Fallen Warrior 1956, cast 1956-7© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Fallen Warrior 1956, cast 1956-7© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Fallen Warrior 1956, cast 1956-7© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Fallen Warrior 1956, cast 1956-7© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Fallen Warrior 1956, cast 1956-7© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Fallen Warrior 1956, cast 1956-7© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Fallen Warrior 1956, cast 1956-7© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Fallen Warrior 1956, cast 1956-7© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Fallen Warrior 1956, cast 1956-7© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Fallen Warrior 1956, cast 1956-7© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Fallen Warrior 1956, cast 1956-7© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Fallen Warrior 1956, cast 1956-7© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Maquette for Fallen Warrior 1956, cast 1956-7© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH,

Maquette for Fallen Warrior

1956, cast 1956-7

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

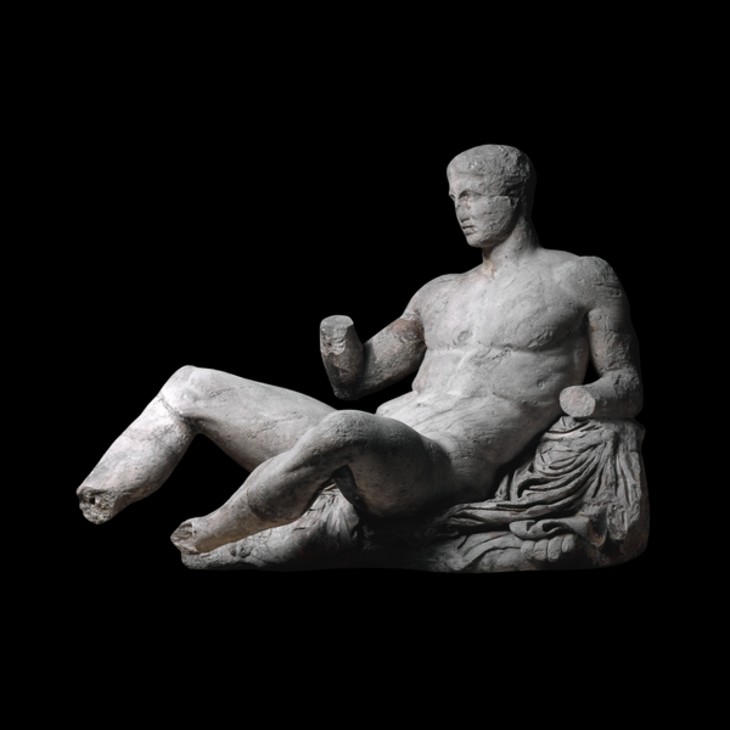

Maquette for Fallen Warrior 1956 is a small-scale bronze sculpture of a naked warrior lying prostrate on its back. Henry Moore depicted male figures very rarely in his work and this sculpture served as a preliminary study for the larger Falling Warrior 1956–7 (Tate T02278). Both these works reveal Moore’s interest in ancient Greek sculpture while alluding to the suffering inflicted by the Second World War.

Henry Moore OM, CH 1898–1986

Maquette for Fallen Warrior

1956, cast 1956–7

Bronze

140 x 155 x 265 mm

Presented by Gustav and Elly Kahnweiler in 1974, accessioned 1994

Number 2 in an edition of 10 plus 1 artist’s copy

T06824

Maquette for Fallen Warrior

1956, cast 1956–7

Bronze

140 x 155 x 265 mm

Presented by Gustav and Elly Kahnweiler in 1974, accessioned 1994

Number 2 in an edition of 10 plus 1 artist’s copy

T06824

Ownership history

Acquired directly from the artist by Gustav and Elly Kahnweiler in July 1957, by whom presented to Tate in 1974, accessioned 1994.

Exhibition history

1978

Henry Moore: 80th Birthday Exhibition, Cartwright Hall, Bradford, April–June 1978 (?another cast exhibited no.117).

2004–5

Cubism and its Legacy: The Gift of Gustav and Elly Kahnweiler, Tate Modern, London, May–November 2004; Tate Liverpool, Liverpool, December 2004–May 2005, no.43.

2010

Henry Moore, Tate Britain, London, February–August 2010, no.140.

References

1960

Will Grohmann, The Art of Henry Moore, London 1960, pp.217–18, reproduced pls.166–7.

1975

John Russell, Henry Moore, London 1975 (armature reproduced fig.78).

1978

Henry Moore: 80th Birthday Exhibition, exhibition catalogue, Cartwright Hall, Bradford 1978 (?another cast reproduced no.117).

1978

80/80, exhibition catalogue, Thomas Gibson Fine Art, London 1978 (another cast reproduced p.27).

1982

Moore Mexico: Escultura, Dibujo, Grafica de 1921 a 1982, exhibition catalogue, Museo de Arte Moderno, Mexico City 1982 (another cast reproduced p.58).

1986

Alan Bowness (ed.), Henry Moore. Volume 3: Sculpture and Drawings 1955–64, 1965, revised edn, London 1986, no.404, reproduced p.27.

1989

Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Fondation Pierre Gianadda, Martigny 1989 (another cast reproduced p.180).

1990

Henry Moore: Sketch Models and Working Models, exhibition catalogue, South Bank Centre, London 1990 (another cast reproduced fig.14).

1992

Henry Moore 1898–1986, exhibition catalogue, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney 1992 (another cast reproduced p.126).

2001

Dorothy Kosinski (ed.), Henry Moore: Sculpting the 20th Century, exhibition catalogue, Dallas Museum of Art, Dallas 2001 (another cast reproduced no.70).

2000

Henry Moore: In the Light of Greece, exhibition catalogue, Basil and Elise Goulandris Foundation Museum of Contemporary Art, Andros 2000, pp.17–51 (another cast reproduced no.20).

2002

Henry Moore: Heads, Figures and Ideas, exhibition catalogue, Musée des Beaux-Arts, Valenciennes 2002 (another cast reproduced p.63).

2004

Giorgia Bottinelli, ‘Henry Moore’, in Jennifer Mundy (ed.), Cubism and its Legacy: The Gift of Gustav and Elly Kahnweiler, exhibition catalogue, Tate Modern, London 2004, pp.82–7, reproduced p.85.

2006

Norbert Lynton, ‘Maquette for Fallen Warrior 1956’ in David Mitchinson (ed.), Celebrating Moore: Works from the Collection of the Henry Moore Foundation, London 2006, pp.251–2 (another cast reproduced).

2007

David Mitchinson (ed.), Moore and Mythology, exhibition catalogue, The Henry Moore Foundation, Perry Green 2007.

2010

Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Tate Britain, London 2010, reproduced p.196.

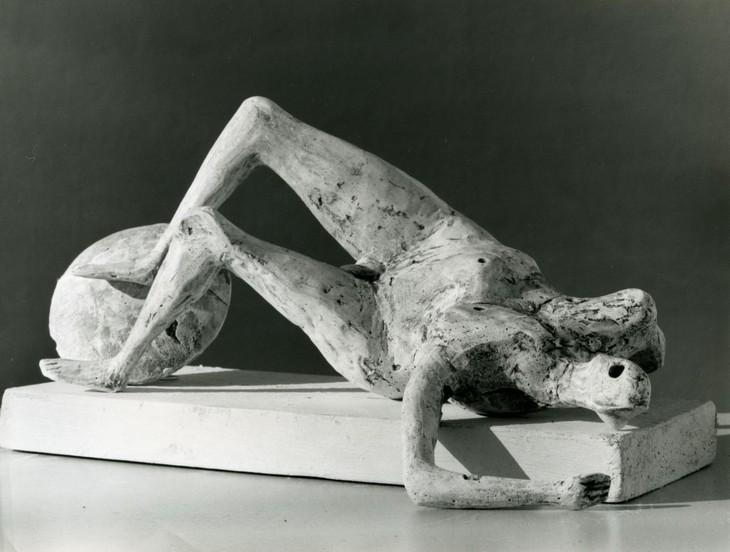

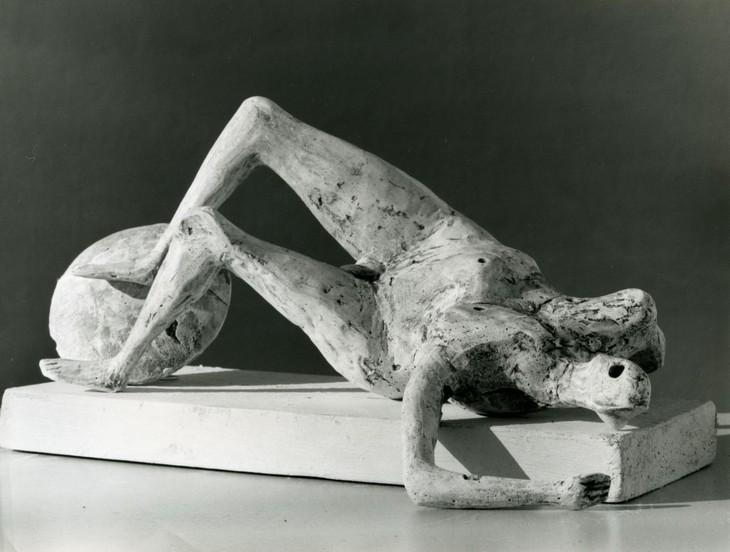

Technique and condition

This small bronze sculpture depicts a figure fallen on its back with a shield at its feet, and lies on a rectangular stepped bronze base. It was originally made in plaster (fig.1) and then sent to a foundry where a mould would have been taken so that it could be cast in bronze. It is possible that the formal origins of this sculpture lie in another work made around the same time, Maquette for Seated Woman 1956 (fig.2), which shares many of the same features with Maquette for Fallen Warrior, including a bulging stomach and indentations below the buttocks. James Copper, a conservator at the Henry Moore Foundation, has suggested that by reorientating a plaster version of this seated figure so that it lay horizontally, and by altering the position of both arms, removing the breasts and remodeling the chest, Moore was able to transform the woman into the male warrior figure.1

Henry Moore

Maquette for Falling Warrior 1956

Plaster

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.1

Henry Moore

Maquette for Falling Warrior 1956

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Henry Moore

Maquette for Seated Woman 1956

Bronze

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.2

Henry Moore

Maquette for Seated Woman 1956

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

The level of detail on the surface of the bronze sculpture suggests that the traditional lost wax technique was used for casting. The flange to the left of the head suggests that Moore utilised a casting overflow made during the creation of the plaster copy and, instead of removing it, incorporated it into the form. There are a few chasing marks on the right leg indicating where casting flashes were removed before the patina was applied.

The surface was artificially coloured a dark brown colour using a chemical patina. This involved applying chemical solutions to the bronze that reacted with the metal to produce coloured surface compounds. An opaque brown patina was applied first and was then rubbed back with a light abrasive so that the original colour of the bronze appeared on high points of the surface. Then a second layer of lighter brown transparent patina was applied to give the final effect before the maquette was coated in protective wax.

The figure is fixed to the base with small screws through the left foot, the left buttock and the shield. The base was sand cast from sections of wood, the original grain of which is still faintly visible on the flat surface of the top step.

Lyndsey Morgan

March 2011

Entry

Maquette for Fallen Warrior is a small bronze sculpture of a male human figure positioned horizontally on a bronze base. A round shield in an upright position is placed at the figure’s feet. Although at first glance the figure appears to be lying on the base, closer inspection reveals that he is only resting on the base at three points: the left heel, the left hip and the right hand. Seen from the front, the figure’s head is to the viewer’s right and the feet are to the left. The base has two tiers that take the form of different sized rectangular steps. The body, head and legs of the figure are positioned on the larger uppermost step, while the left arm extends downwards onto the lower, narrower step at the front.

Although the figure is recognisably a human male, Maquette for Fallen Warrior is not represented naturalistically. The arms and legs are particularly skinny and the head is disproportionately small when compared to the larger, bulbous belly and buttocks. When seen from the side the figure appears to be curved; the head and the feet are placed towards the front of the upper tier of the base while the hips are twisted towards the rear (fig.1). The figure appears to be writhing and much of the body is balanced on the left hip.

The head is represented by an oval disk, which is pierced by a single hole that creates a short tunnel linking the left and right sides of the face (fig.2). This hole appears to denote the eyes of the figure. On the left side of the head a thin ridge protrudes sideways, which may represent an ear. The ridge extends over the crown of the head to the right side, extending outwards to create a right ear. No other facial features have been represented apart from a slight curve and incision that distinguishes the chin from the neck.

Henry Moore

Maquette for Fallen Warrior 1956, cast 1956–7 (view from head)

Tate T06824

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.1

Henry Moore

Maquette for Fallen Warrior 1956, cast 1956–7 (view from head)

Tate T06824

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Detail of head of figure in Maquette for Fallen Warrior 1956, cast 1956–7

Tate T06824

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.2

Detail of head of figure in Maquette for Fallen Warrior 1956, cast 1956–7

Tate T06824

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

The neck leads to a heavily defined chest with clearly incised fan-shaped pectoral muscles, each marked with a shallow, circular indentation denoting nipples (fig.3). However, while the left pectoral appears smooth and muscular, the surface of the right muscle is rough, giving the impression that it is sunken and that bones are pushing against the skin. From these differing forms the stomach swells to a rounded peak, and is capped with a small round indentation denoting the navel. Moving along the length of the body the stomach then dips sharply to the figure’s genitalia. The weight of the sculpture seems to have amassed in the stomach and hip areas, which are made of curved and rounded forms. The heavy middle of the figure is accentuated by the slender limbs.

Detail of figure's chest in Maquette for Fallen Warrior 1956, cast 1956–7

Tate T06824

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.3

Detail of figure's chest in Maquette for Fallen Warrior 1956, cast 1956–7

Tate T06824

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Detail of figure's right arm in Maquette for Family Group 1956, cast 1956–7

Tate T06824

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.4

Detail of figure's right arm in Maquette for Family Group 1956, cast 1956–7

Tate T06824

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

From the back of the sculpture the right shoulder appears to be anatomically incorrect; the shoulder socket seems to have been stretched so that it protrudes sideways, away from the body. The skinny upper arm extends from this socket to the elbow below, which is bent so that the hand, the fingers of which are curled into a fist, is wedged between the base and the right buttock (fig.4). The meager left arm is curved unnaturally from the shoulder and extends on a downward diagonal over the upper tier of the base. The left elbow rests on the lower step where the forearm is extended pointing towards to the right-hand edge. The arm does not sit flush on the base and a small gap can be seen between the base and the wrist. The hand is mitten-shaped, and although five fingers have been suggested by incised lines, none of the fingers have been individually separated.

The knees of both legs are bent and drawn towards the body. Although the left foot is resting on the base, the right leg is suspended in the air, with the right knee the highest point of the sculpture. The frontal planes of the right and left thighs are fairly straight but the undersides each have sharp triangulated cuts where they meet the lower buttocks. From each knee the calves of the legs extend to narrow ankles and heels. While the right shin is fairly rounded, the left shin has a straight blade-like ridge running from the knee to the ankle (fig.5). The feet widen at the toes, which are denoted on each foot by incised lines, but which have not been individuated separately. The heel of the left foot rests on the base while the rest of the foot is lifted slightly away from it. The circular domed shield is placed standing upright behind the feet, with the convex surface facing the front.

The base colour of the sculpture is almost black, on top of which golden-brown shades accentuate the higher points of the sculpture such as the right knee, the top of the stomach, the left shoulder and the front of the face. The surface of the bronze replicates the surface of the plaster model from which it was cast, and no seams are visible on the surface of the figure, which suggests that it was cast in one piece. However, chasing marks can be seen on the right leg indicating where the rods that were used in the casting process have been removed. The shield was cast separately and is held in place by a small screw that runs through the base. The figure is fixed to the base with small screws in the left foot and the left buttock, although none of these fixtures are visible.

Henry Moore

Maquette for Fallen Warrior 1956, cast 1956–7 (view from legs)

Tate T06824

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.5

Henry Moore

Maquette for Fallen Warrior 1956, cast 1956–7 (view from legs)

Tate T06824

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

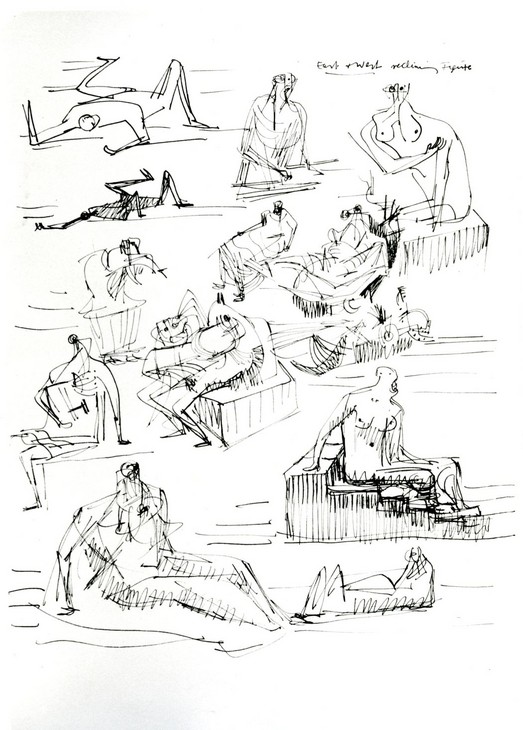

Henry Moore

Figure Studies 1955–6

Pen and ink on paper

Private collection

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.6

Henry Moore

Figure Studies 1955–6

Private collection

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

At the time Maquette for Fallen Warrior was created, Moore rarely made preparatory drawings for specific sculptures, preferring instead to sketch general ideas and work directly in plaster, utilising his accumulated knowledge of bodily forms to make his initial three-dimensional models. Nonetheless, it is possible to identify drawings that illuminate the evolution of Moore’s warrior sculptures. In particular, a sketch titled Figure Studies 1955–6 (fig.6) contains two pen and ink drawings of supine figures with raised arms and bent knees.

Henry Moore

Maquette for Falling Warrior 1956

Plaster

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.7

Henry Moore

Maquette for Falling Warrior 1956

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Henry Moore

Maquette for Seated Woman 1956

Bronze

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.8

Henry Moore

Maquette for Seated Woman 1956

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

It is probable that Moore made his plaster model of Maquette for Fallen Warrior (fig.7) in his maquette studio in the grounds of his home, Hoglands, at Perry Green in Hertfordshire. The conservator at the Henry Moore Foundation, James Copper, has suggested that this sculpture developed from (or concurrently with) Maquette for Seated Woman (fig.8).1 It is known that Moore often recycled his plaster maquettes, and the position of the warrior’s legs, bulbous stomach and the sharp cuts between the thigh and the buttock all correspond to the features of the seated figure. Having made Maquette for Seated Woman in plaster, it would not have been difficult to make a copy, and remodel the arms and head in order to reconfigure the work as a fallen male. According to Moore, ‘The advantage of using plaster is that it can be both built up, as in modelling, or cut down, in the way you carve stone or wood’.2 Due to the nature of the material, Moore would have been able to file away the breasts and reconfigure the chest of the maquette and model the figure’s penis. The fact that Moore’s sketches of prostrate figures appear alongside drawings of seated women in Figure Studies indicates that he was thinking about these two different compositional forms simultaneously in 1955–6. Maquette for Seated Woman was cast in a bronze edition of nine in 1956, an example of which is held in the collection of the Henry Moore Foundation; it was enlarged in 1957 as Seated Woman (Tate T02279).

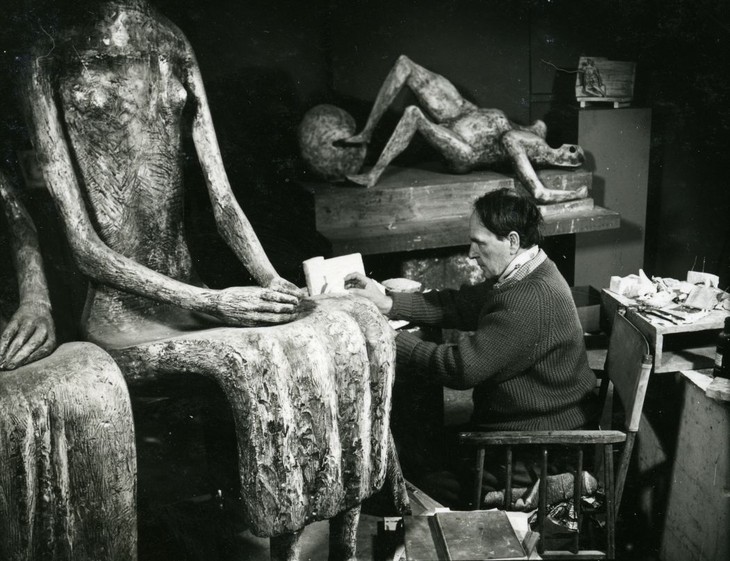

Henry Moore in his studio with full-size plaster version of Falling Warrior 1956–7

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: John Hedgecoe

Fig.9

Henry Moore in his studio with full-size plaster version of Falling Warrior 1956–7

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: John Hedgecoe

Henry Moore OM, CH 1898–1986

Falling Warrior 1956–7, cast c.1957–60

Bronze

object: 650 x 1540 x 850 mm

Tate T02278

Presented by the artist 1978

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.10

Henry Moore OM, CH

Falling Warrior 1956–7, cast c.1957–60

Tate T02278

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

The purpose of making a plaster maquette is to consider the form and composition of the sculpture before making a final, larger plaster version that can then be used to cast the sculpture in bronze. A photograph of Moore in his studio shows the completed full-size plaster version of the sculpture (fig.9). However, it seems that having completed this larger version Moore was dissatisfied with the final result because he changed the subject from that of a fallen figure, whose body is in contact with the ground, to a falling figure, which appears suspended in motion while tumbling backwards. The large bronze sculpture Falling Warrior 1956–7 (Tate T02278; fig.10) was the result of this change. Moore later explained that:

In the Falling Warrior sculpture I wanted a figure that was still alive. The pose of the first maquette was that of a completely dead figure and so I altered it to make the action that of a figure in the act of falling, and the shield became a support for the warrior, emphasising the dramatic moment that precedes death.3

The body of the figure in Maquette for Fallen Warrior is slumped on the base and does not capture the moment prior to death as Moore had wished. At the time he made the maquette, then, it seems that Moore had not intended to make two distinct versions of the warrior, and that the different titles of the two bronze sculptures were probably given retrospectively in order to distinguish between them.

Despite his reservations about the pose of Maquette for Fallen Warrior, Moore nonetheless decided to cast the smaller plaster in bronze. By 1956 it was quite usual for Moore to cast his maquettes and from about 1955 he re-cast in bronze a number of small sculptures that had originally been made in lead during the 1930s (see Reclining Figure 1939, Tate T00387). The decision to cast small works in bronze editions was probably driven by financial reasons. In the early 1940s Moore had found that the sale of his small bronze maquettes, such as Maquette for Madonna and Child 1943 (Tate N05600), could off-set the costs of casting much larger sculptures in bronze. In addition, by the mid-1950s Moore’s work was also in much greater demand by collectors and patrons and producing smaller works in editions of eight or nine would have been a practical way of satisfying this demand. During the 1950s Moore worked with a number of different London-based commercial galleries including Roland Browse and Delbanco, Gimpel Fils, and the Leicester Galleries, all of which sold small, domestic scale sculptures by Moore that could be placed on table tops.

Moore employed the Art Bronze Foundry in London to cast Maquette for Fallen Warrior. Moore had previously commissioned this foundry to cast his Maquette for Madonna and Child and he continued to use their services throughout the 1950s. The foundry had been established in 1922 by Charles Gaskin and by 1953 was located just off the Kings Road in London. It is likely that Moore first came into contact with the foundry when he was head of the Sculpture Department at Chelsea College of Art in the 1930s for the foundry was located close to the college and was regularly used by staff and students.

It is likely that this sculpture was cast using the lost wax technique, which involved first creating a mould of the plaster sculpture into which molten wax could be poured to create a perfect wax replica of the sculpture. After hardening, the wax replica would then be encased in a hard refractory material and placed in a kiln. Tubular channels within the casing would allow the wax to drain away when it melted, leaving a hollow cavity into which molten bronze would be poured. For the finished bronze sculpture to be flawless the bronze had to be poured in one go. Once the bronze had cooled and hardened the casing could be removed to reveal the finished sculpture.4 Maquette for Fallen Warrior exists in an edition of ten plus one artist’s cast. Given that Tate’s sculpture was collected by its original owners, Gustav and Elly Kahnweiler, from Moore’s studio on 8 July 1957, it is likely that the sculpture was cast in late 1956 or early 1957.5 Although it would have been expensive, by the later 1950s Moore was able to afford the costs of casting and it is possible that all ten bronzes in the edition were cast either in quick succession or at the same time.6 At the time the Kahnweilers acquired their sculpture, Maquette for Fallen Warrior was priced at approximately £100.7

After casting at the foundry the bronze sculpture was returned to Moore so that he could check the quality of the casting and make decisions about the patination. A patina refers to the surface colour of a sculpture and is usually achieved by applying chemical solutions to the pre-heated bronze sculpture. According to curator Julie Summers, Moore sought to ‘produce a unity between patina and form’ in his sculptures, so that the colours complimented the shapes on which they were applied.8 Moore noted that when working on his plasters he normally had a preconceived idea of what colour the sculpture would eventually take:

I usually have an idea, as I make the plaster, whether I intend it to be a bark or a light bronze, and what colour it is going to be. When it comes back from the foundry I do the patination and this sometimes comes off happily, though sometimes you can’t repeat what you’ve done other times. The mixture of bronze may be different, the temperature to which you heat the bronze before put the acid on to it may be different. It is a very exciting but tricky and uncertain thing, this patination of bronze.9

According to Summers Moore did not look upon the difficultly of replicating patinas as a problem. Indeed, she suggested that ‘a variation in colour within the edition also represented an element of choice for the potential client’.10

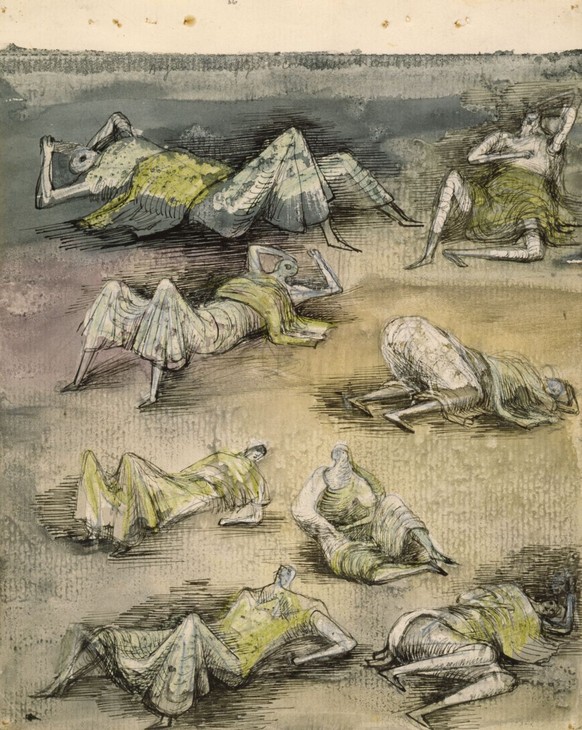

Henry Moore

Sleeping Positions 1941

Graphite, wax crayon, pen, ink and watercolour wash on paper

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Michel Muller, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.11

Henry Moore

Sleeping Positions 1941

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Michel Muller, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Following the critical success of Moore’s Shelter Drawings, the critic Herbert Read suggested to the artist that he undertake a second commission from the War Artists Committee, this time depicting ‘Britain’s Army Underground’, the coal miners who ensured the regular supply of fuel for the nation during the Second World War. In 1947 Moore reflected that:

It was difficult, but something I am glad to have done. I have never willingly drawn male figures before – only as a student in college. Everything I had willingly drawn was female. But here, through these coal-mining drawings, I discovered the male figure and the qualities of the figure in action. As a sculptor I had previously believed only in static forms, that is forms in repose.11

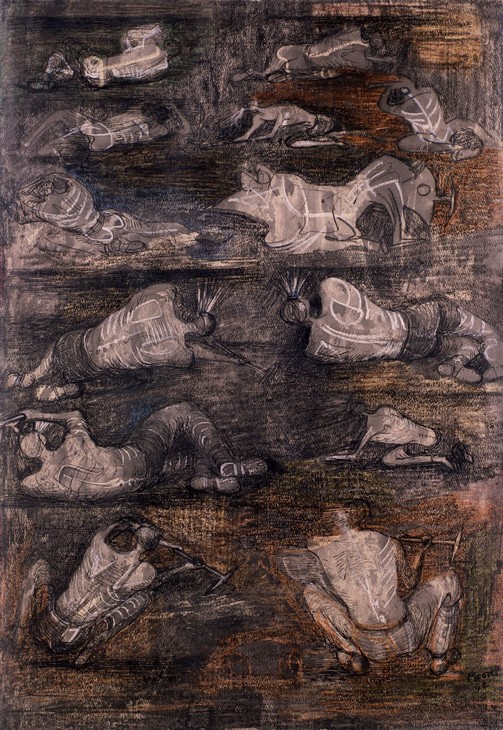

Henry Moore

Miners at Work 1942

Graphite, wax crayon, coloured crayon, watercolour wash, pen and ink on paper

Private collection

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Rodney Todd-White & Son, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.12

Henry Moore

Miners at Work 1942

Private collection

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Rodney Todd-White & Son, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

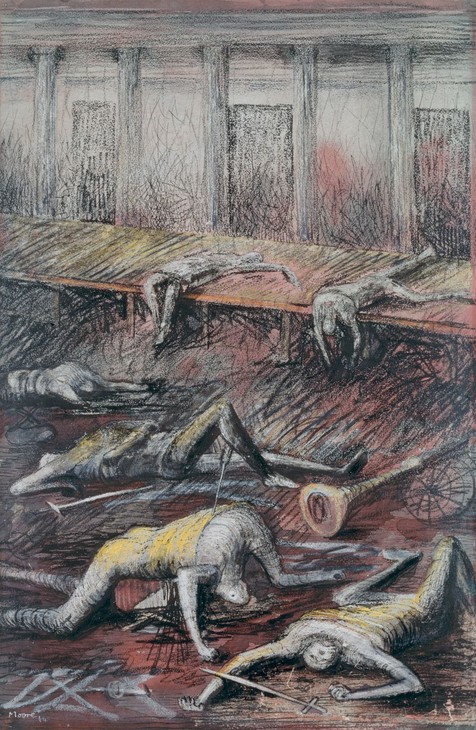

Henry Moore

The Death of the Suitors 1944

Graphite, wax crayon, coloured crayon, watercolour wash, pen and ink, brush and ink on paper

Cecil Higgins Art Gallery, Bedford

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.13

Henry Moore

The Death of the Suitors 1944

Cecil Higgins Art Gallery, Bedford

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

In his coal mining drawings Moore undertook his first sustained examination of the male figure. The figure second from bottom on the left side of Miners at Work 1942 (fig.12) might be regarded as a graphic precursor to the figure in Maquette for Fallen Warrior: this figure is lying on his side, with his right arm lifted above his head. His twisted and curved body is tucked into a compact space and looking upwards he seems to be conscious that the roof could collapse. Kenneth Clark, who was Director of the National Gallery when he appointed Moore as an Official War Artist, later reflected that ‘such a figure as the fallen warrior would not have come into existence with out the drawings of miners working on their backs’.12

According to the art historian Frances Carey, the angular, twisted figures found in Sleeping Positions reappear in the later drawing The Death of the Suitors 1944 (fig.13), one of a series of drawings created to illustrate Edward Sackville-West’s play The Rescue.13 The play was based on Homer’s Odyssey and Moore’s image depicts the aftermath of Odysseus’s rampage when, on returning home after fighting in the ten-year Trojan War, he kills the 108 suitors courting his wife Penelope. In 1970 the art critic Robert Melville regarded the male suitors in the drawing as studies for sculptures, suggesting that the violent scene ‘presents a fascinating spectacle of terracottas dying in a blood-red room’.14 Between 1949 and 1950 Moore also worked on lithographs for André Gide’s translation of Goethe’s Prometheus, itself based on Aeschylus’s ancient tragedy Prometheus Bound. As the curator David Mitchinson has remarked, in these lithographs, as in The Death of the Suitors, ‘male flesh is perceived as being just as vulnerable as female’.15

Henry Moore

Reclining Warrior 1953

Painted plaster

90 x 197 x 95 mm

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.14

Henry Moore

Reclining Warrior 1953

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Henry Moore

Warrior with Shield 1953–4

Bronze on wood plinth

1530 x 660 x 830 mm

Birmingham Museums and Art Gallery

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.15

Henry Moore

Warrior with Shield 1953–4

Birmingham Museums and Art Gallery

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

The injured or traumatised male body was an infrequent but recurring subject in Moore’s work. Following his drawings of sleeping and dying figures of the 1940s, the painted plaster sculpture Reclining Warrior 1953 (fig.14), which was also cast in bronze, signals the start of Moore’s engagement with the male warrior subject in three-dimensional form. In 1955 Moore explained:

The idea for The Warrior came to me at the end of 1952 or very early in 1953. It was evolved from a pebble I found on the seashore in the summer of 1952, and which reminded me of the stump of a leg, amputated at the hip. Just as Leonardo says somewhere in his notebooks that a painter can find a battle scene in the lichen marks on a wall, so this gave me the start of The Warrior idea. First I added the body, leg and one arm and it became a wounded warrior, but first the figure was reclining.16

Moore then amended the orientation of Reclining Warrior, changing it from a supine to a seated position. In Moore’s opinion this amendment, with the addition of a shield, changed the sculpture ‘from an inactive pose into a figure which, though wounded, is still defiant’.17 This new version, Warrior with Shield 1953–4 (fig.15), was an exciting departure for Moore, who explained: ‘This sculpture is the first single and separate male figure that I have done in sculpture and carrying it out in its final large scale was almost like the discovery of a new subject matter; the bony, edgy, tense forms were a great excitement to make’.18

Although there was a pause of a few years between the creation of Warrior with Shield and Maquette for Fallen Warrior and its full-size version, Falling Warrior, the sculptures could nonetheless be said to constitute a series and are usually discussed together by commentators on Moore’s work. The scholar Will Grohmann, for example, has argued that Moore’s warriors originated from his interest in classical Greek sculpture and mythology, in particular from his engagement, albeit indirectly, with the texts of Homer and Aeschylus.19 For example, Grohmann described Warrior with Shield thus: ‘He is only a warrior, the prototype of the warrior, who has been defeated and mutilated in a murderous battle such as Homer sings of, who has lost his left arm and left leg and right foot, who has no weapon left but his shield, behind which he hides the remnant of his pitiable existence’.20 Grohmann went on to suggest that Moore’s figures of the fallen and falling warriors are ‘most brutal of all’.21 He noted that ‘from some view points the Fallen Warrior looks like a miserable reptile, especially as the head is not much more than a perforated, elongated knob and the long arms and legs those of a lifeless puppet. There is nothing conciliatory about this fallen hero, nothing that mitigates the brutality, and perhaps that is why Moore modified him’.22 Grohmann concluded that ‘although there is nothing epic in the Falling Warrior, it contains the essence of the Homeric tale’.23 Following Grohmann’s interpretation, art historian Roger Cardinal has suggested that it was Homer’s Iliad, rather than his Odyssey, which gave rise to Moore’s warrior imagery. Moore is known to have read and appreciated the Iliad with its accounts of ‘brave swordsmen succumbing to horrendous battle-wounds’.24

For Herbert Read the affinity between Moore’s warriors and ancient Greek sculpture was beyond doubt. Of Warrior with Shield he stated ‘there is a distinct Hellenic note, and it is the direct result of a visit to Greece which the sculptor made in 1951’.25 This trip, which was Moore’s first and only visit to the country, had a significant effect on his work, as he explained in an interview conducted in 1961:

Mycenae had a tremendous impact. I felt that I understood Greek tragedy and – well the whole idea of Greece – much, much more completely than ever before. And Delphi, though I did find it had a slight tough of theatricality, as if eagles were flying round to order, and Olympia, with the idyllic sense of lovely living that you get there, and of course the whole of the Acropolis. That too had something I hadn’t at all foreseen.26

Moore also acknowledged that ‘I think The Warrior [with Shield] has some Greek influence, not consciously wished for but perhaps the result of my visit to Athens and other parts of Greece in 1951’.27 Despite his hesitancy, Moore’s choice of subjects in the 1950s – draped reclining women and warriors with shields – are certainly variants of those found in ancient Greek art. Indeed Cardinal has described them as ‘a sequence of works of a decidedly Greek tinge’.28 That Moore’s warriors of the 1950s are armed with a curved shield places them outside of the contemporary moment in which they were made; the shield, with the titular use of the term ‘warrior’ rather than ‘soldier’ suggests that the figures belong to the past.

Although Maquette for Fallen Warrior cannot be directly linked to a single example of Greek sculpture, and Moore may have drawn on any number of examples when he made it, Cardinal nonetheless drew attention to the Fallen Warrior from the Temple of Aphaia on the island of Aegina (fig.16), which depicts a fallen male warrior holding onto his round shield while falling and twisting towards the ground. For Cardinal this ancient fallen warrior is exemplary of the type of imagery Moore would have been exposed to during his trip to Greece, and it is possible that Moore would have been familiar with this particular example from reproductions. Moore’s Maquette for Fallen Warrior seems to replicate the tension and downward motion of the Greek example, as well as its twisted and wounded body.

However, even before his visit to Greece Moore had studied the Parthenon marbles housed in the British Museum. An illustration of one of these sculptures – the nude figure of Dionysos from 438–423 BC (fig.17) – was included in the ‘comparative material’ section of the catalogue to his 1968 Tate exhibition. In the same catalogue the exhibition’s curator David Sylvester suggested that Moore’s reclining figures could be understood in relation to the ‘Mediterranean tradition’.29 The sculpture of Dionysos was of particular interest to Moore and in 1981 a series of three photographic illustrations of it were included in the publication Henry Moore at the British Museum. For this book Moore selected and discussed artworks from the British Museum’s collection that had influenced him during his career. Moore stated that:

The sculptor who did this had a thorough understanding of the human figure, and shows so realistically the differences between the slackness of flesh and the hardness of the bone beneath it. I knew, as a young sculptor, that I had to learn all I could about the human figure, but I rather took the Greeks for granted and didn’t realise till much later how deep was their observation of human form. But this piece always attracted me, perhaps because of my interest in reclining figures.30

Fallen Warrior from the east pediment of the Temple of Aphaia c.490–480 BC

Glyptothek, Munich

Fig.16

Fallen Warrior from the east pediment of the Temple of Aphaia c.490–480 BC

Glyptothek, Munich

Figure of Dionysos from the east pediment of the Parthenon c.438–432 BC

British Museum, London

© Trustees of the British Museum

Fig.17

Figure of Dionysos from the east pediment of the Parthenon c.438–432 BC

British Museum, London

© Trustees of the British Museum

Cardinal suggested that the broken and fragmentary nature of the Greek examples in the British Museum and elsewhere was a particular inspiration to Moore. As demonstrated in the incomplete bodies of Reclining Warrior and Warrior with Shield ‘fragmentariness is itself an integral part of Moore’s creative vocabulary’.31 This damage to the body may have resonated with Moore when making his wounded warriors.

Considerations of Moore’s warrior sculptures of the 1950s in relation to his interest in classical sculpture and his 1951 trip to Greece have dominated critical discussions of these works. Such was Grohmann’s conviction that Moore’s Falling Warrior and the two other warrior sculptures were based on Greek sculptural traditions that in 1960 he refuted alternative visual references for these works – principally Moore’s experiences of war. Grohmann stated that Moore’s decision to create a series of warriors in the 1950s ‘cannot be explained by his war experience in London or the re-awakening of dreamlike memories of the First World War. It is certainly not the remoteness in time that makes this unlikely, but the figure of the “Warrior” itself, which has nothing to do with the anonymous, technological mass slaughter’.32

However, in 1955 Moore noted in relation to Warrior with Shield that ‘The figure may be emotionally connected (as one critic has suggested) with one’s feelings and thoughts about England during the crucial and early part of the last war. The position of the shield and its angle gives protection from above’.33 In 1970 the critic Robert Melville stated that Moore’s warrior theme ‘discloses an overt concern with the miseries of war’.34 This interpretation was echoed in 2008 by art historian Christa Lichtenstern, who suggested that not only can the warrior subject be directly linked to slaughtered soldiers of the Second World War, but that Moore’s reference to the shield giving ‘protection from above’ alluded to the aerial bombardments suffered by cities including Coventry, Dresden, and Hiroshima. The composition of Maquette for Fallen Warrior similarly suggests an attack from above. Given that Moore’s supine warriors may have originated from his Shelter Drawings, the Coal Mining drawings, and those made for Edward Sackville-West’s The Rescue, it may be possible to view Moore’s warriors of the 1950s as extensions of and developments on his war-time imagery. Tate curator Chris Stephens has also suggested that Moore’s depiction of a soldier at the moment of falling may have some relation to Robert Capa’s famous photograph Loyalist Militiaman at the Moment of Death, Cerro Muriano, September 5, 1936 1936, first published in September 1936 in the French magazine Vu.35 It is known that Moore was sympathetic to the loyalist cause during the Spanish Civil War and it is likely that he knew of the image by the time he was working on Maquette for Fallen Warrior.36

In a television programme titled England’s Henry Moore, first broadcast on Channel 4 on 21 September 1988, the Marxist literary critic and filmmaker Anthony Barnett proposed that many of the subjects and forms of Moore’s work may be attributed to his experiences during the First World War. Moore served as a gunner in the battle of Cambrai in late 1917; he was one of fifty-two survivors from his battalion of 400. During the attack Moore suffered gas poisoning and was hospitalised for three months. Obliquely referencing these experiences, in 1974 Clark wrote that ‘the deep, disturbing well from which emerged his finest drawings and sculpture was never referred to and no one meeting him could have guessed at its existence’.37 Barnett, and subsequently the curators Jeremy Lewison and Chris Stephens, noted this aporia, suggesting that Moore’s memories of warfare and the sight of fallen, mutilated bodies permeated much of his work.38

Moore rarely explained his work with reference to contemporary events, preferring instead for sculptures such as Maquette for Fallen Warrior to stand as ahistorical symbols of and for a shared human condition. According to David Mitchinson:

Moore’s treatment of male subjects followed a clear pattern. In sculpture, as in his drawings and lithographs, they were never aggressive, militaristic, or bombastic ... All three of Moore’s warriors have shields, a classic item of defense, but no weapons of attack such as swords or spears. The shields when viewed as a traditional form of protection can be compared to the helmets in the helmet heads, or the exterior elements of the internal/external forms – hard defensive barriers safeguarding what lies beneath.39

In light of Mitchinson’s observations, Maquette for Fallen Warrior may be regarded not as an updated reworking of a classical subject, or as a representation of the suffering caused by the Second World War, but rather as a more generalised depiction and reminder of the fragility of human life. Moore’s recognition that tragedy could befall anyone at any time was perhaps reinforced during his visit to the archaeological site of Pompeii in 1954. Here Moore witnessed the consequences of a natural catastrophe – the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in AD 79 – which buried the Roman town in volcanic ash. During his visit Moore was particularly intrigued by the plaster casts of preserved corpses lying on the ground, which he photographed from various angles (fig.18). Caught at the moment of their death these casts show the vulnerability of the body and Maquette for Fallen Warrior recalls the poses of these tragic figures.

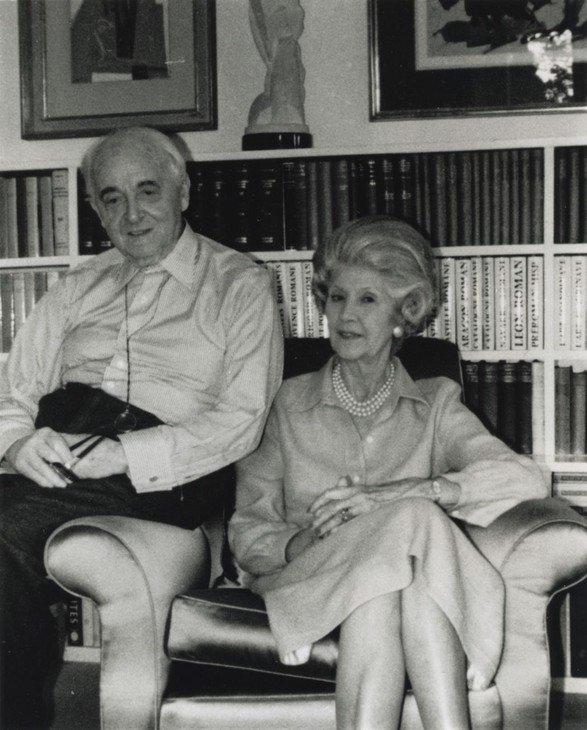

Gustav and Elly Kahnweiler at Alderbourne Manor, Buckinghamshire

Tate Archives

Fig.19

Gustav and Elly Kahnweiler at Alderbourne Manor, Buckinghamshire

Tate Archives

It is not known how or when the Kahnweilers first met Henry Moore, but they may have become familiar with his work in the late 1930s when Moore exhibited at the Mayor Gallery in London, one of the few commercial galleries that actively exhibited and supported the work of modern artists working in Britain and continental Europe. Nonetheless, by the 1950s the Kahnweilers, Moore and Moore’s wife Irina shared a warm friendship. As well as purchasing works by Moore for their own collection, Gustav acted occasionally as an agent in the sale of Moore’s sculptures. For example, in 1952 he negotiated the sale of Moore’s sculpture to the Kunstmuseum in Basel. The Kahnweilers acquired Maquette for Fallen Warrior directly from Moore shortly after it was cast, and it remained in their apartment at Alderbourne Manor, Buckinghamshire, where the couple had lived since 1956, until it entered the Tate’s collection.

When he died Gustav left detailed instructions regarding the Tate’s gift, and following Elly’s death a total of fifty-five artworks entered the Tate’s collection, including works by Georges Braque, Paul Klee, Henri Laurens, André Masson and Picasso. Along with Maquette for Fallen Warrior, four other sculptures by Henry Moore were included in the Kahnweiler Gift: Maquette for Standing Figure 1950 (Tate T06827), Reclining Figure: Bunched 1961 (Tate T06826), Maquette for Figure on Steps 1956 (Tate T06828), and Draped Reclining Woman 1957–8 (Tate T06825).

Maquette for Fallen Warrior is number two in an edition of ten, plus one artist’s cast. Other casts are held in the collections of the Henry Moore Foundation, the British Council, and the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden in Washington, D.C. The remaining examples are believed to be held in private collections.

Alice Correia

February 2013

Notes

James Copper, Sculpture Conservator, The Henry Moore Foundation, in conversation with the author, 31 July 2013.

For a video explaining the lost wax process, see http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/articles/s/sculpture-techniques/ , accessed 23 January 2014.

See Julie Summers, ‘Gilding the Lily: The Patination of Henry Moore’s Bronze Sculptures’, in Jackie Heuman (ed.), From Marble to Chocolate: The Conservation of Modern Sculpture, London 1995, p.145.

Henry Moore cited in Donald Hall, ‘Henry Moore: An Interview by Donald Hall’, Horizon, November 1960, p.113, reprinted in Alan Wilkinson (ed.), Henry Moore: Writings and Conversations, Aldershot 2002, p.234.

Henry Moore cited in James Johnson Sweeney, ‘Henry Moore’, Partisan Review, March–April 1947, pp.184–5, reprinted in Wilkinson 2002, p.266.

Frances Carey, ‘Sleeping Positions 1941’, in David Mitchinson (ed.), Celebrating Moore: Works from the Collection of the Henry Moore Foundation, London 2006, p.191.

David Mitchinson, ‘Moore and Mythology’ in David Mitchinson (ed.), Moore and Mythology, exhibition catalogue, The Henry Moore Foundation, Perry Green 2007, p.15.

Roger Cardinal, ‘Henry Moore: In the Light of Greece’, in Henry Moore: In the Light of Greece, exhibition catalogue, Basil and Elise Goulandris Foundation Museum of Contemporary Art, Andros 2000, p.44.

Herbert Read, ‘Introduction’, in Alan Bowness (ed.), Henry Moore. Volume 2: Sculpture and Drawings 1949–1955, 1955, 2nd edn London 1965, pp.x–xi.

Henry Moore cited in John and Vera Russell, ‘Conversations with Henry Moore’, Sunday Times, 24 December 1961, reprinted in Wilkinson 2002, p.69.

See Henry Moore, letter to Raymond Coxon and Edna Ginesi [Peacham & Gin], [August/September 1936], Tate Archive.

See Jeremy Lewison, Henry Moore 1898–1986, Cologne 2007, and Chris Stephens, ‘Anything But Gentle: Henry Moore – Modern Sculptor’, in Chris Stephens (ed.), Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Tate Britain, London 2010, pp.12–17.

David Mitchinson, ‘Introduction: War and Utility’, in Henry Moore: War and Utility, exhibition catalogue, Imperial War Museum, London 2006, p.16.

Related essays

- Scale at Any Size: Henry Moore and Scaling Up Rachel Wells

- 'I tried to push him down the stairs': John Berger and Henry Moore in Parallel Tom Overton

- Henry Moore's Approach to Bronze Lyndsey Morgan and Rozemarijn van der Molen

Related catalogue entries

Related material

-

Henry MooreLetter to Raymond Coxon and Edna Ginesi (Peacham & Gin) Late August/ early September 1936Letter

How to cite

Alice Correia, ‘Maquette for Fallen Warrior 1956, cast 1956–7 by Henry Moore OM, CH’, catalogue entry, February 2013, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015, https://www