Henry Moore OM, CH Large Totem Head 1968, cast date unknown

Image 1 of 16

-

Henry Moore OM, CH, Large Totem Head 1968, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Large Totem Head 1968, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Large Totem Head 1968, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Large Totem Head 1968, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Large Totem Head 1968, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Large Totem Head 1968, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Large Totem Head 1968, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Large Totem Head 1968, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Large Totem Head 1968, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Large Totem Head 1968, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Large Totem Head 1968, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Large Totem Head 1968, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Large Totem Head 1968, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Large Totem Head 1968, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Large Totem Head 1968, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Large Totem Head 1968, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Large Totem Head 1968, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Large Totem Head 1968, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Large Totem Head 1968, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Large Totem Head 1968, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Large Totem Head 1968, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Large Totem Head 1968, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Large Totem Head 1968, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Large Totem Head 1968, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Large Totem Head 1968, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Large Totem Head 1968, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Large Totem Head 1968, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Large Totem Head 1968, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Large Totem Head 1968, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Large Totem Head 1968, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Large Totem Head 1968, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Large Totem Head 1968, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH,

Large Totem Head

1968, cast date unknown

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

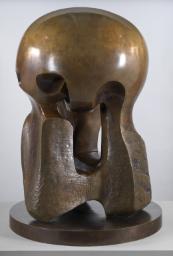

The form of this large sculpture draws on designs made by Moore in the 1930s that reflect his interest in the totemic symbolism of so-called ‘primitive’ art. It also relates to the artist’s preoccupation with hollowed, interior spaces, which developed in the 1950s. As the title indicates, the sculpture may be understood as a head, although the small maquette from which it originated was also described as a boat.

Henry Moore OM, CH 1898–1986

Large Totem Head

1968, cast date unknown

Bronze

2458 x 1341 x 1258 mm

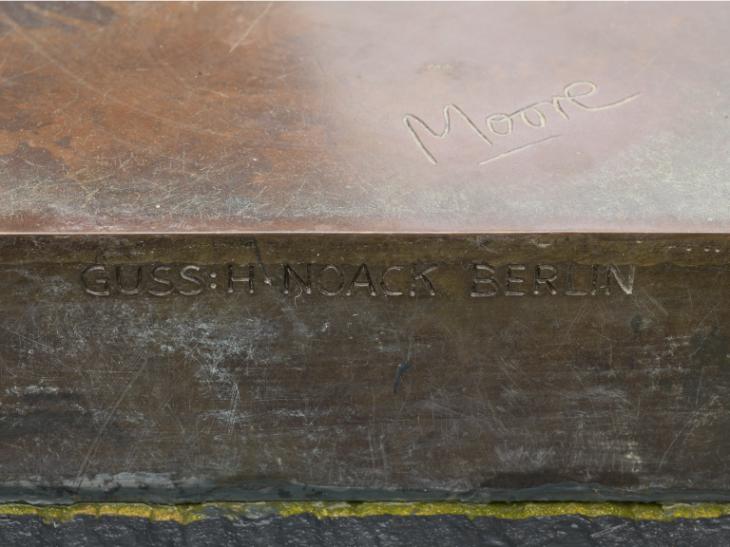

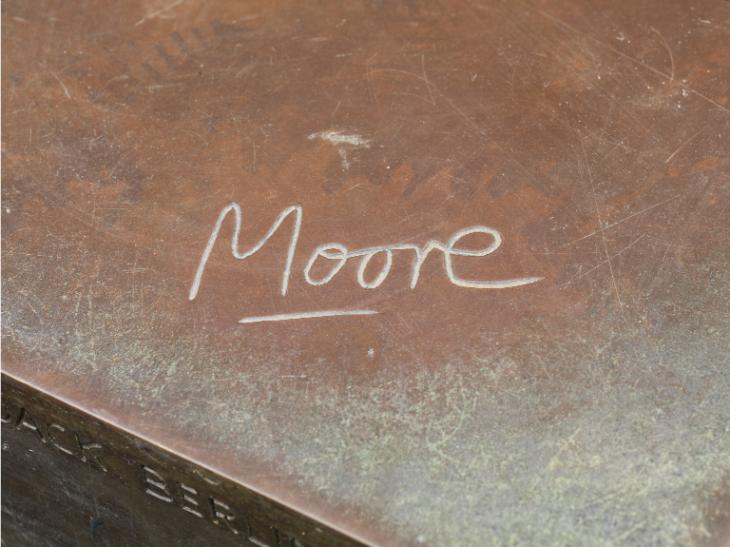

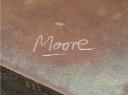

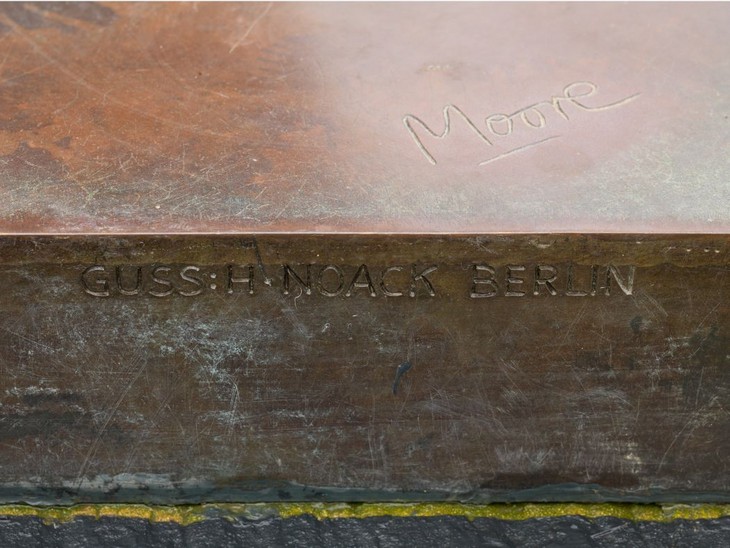

Inscribed ‘Moore’ on base and stamped with foundry mark ‘GUSS: H. NOACK BERLIN’ on side of base

Presented by the artist 1978

In an edition of 8 plus 1 artist’s copy

T02302

Large Totem Head

1968, cast date unknown

Bronze

2458 x 1341 x 1258 mm

Inscribed ‘Moore’ on base and stamped with foundry mark ‘GUSS: H. NOACK BERLIN’ on side of base

Presented by the artist 1978

In an edition of 8 plus 1 artist’s copy

T02302

Ownership history

Presented by the artist to Tate in 1978 as part of the Henry Moore Gift.

Exhibition history

1968

Henry Moore, Rijksmuseum Kröller-Müller, Otterlo, May–July 1968; Museum Boymans-Van Beuningen, Rotterdam, September–November 1968, no.123.

1970

Henry Moore: Bronzes 1961–70, Marlborough Gallery, New York, April–May 1970, no.30.

1976

The Work of the British Sculptor Henry Moore, Zürcher Forum, Zürich, June–August 1976, no.87.

1978

The Henry Moore Gift, Tate Gallery, London, June–August 1978, no number.

1987

Henry Moore and Landscape, Yorkshire Sculpture Park, West Bretton, May–August 1987, no.21.

References

1977

Alan Bowness (ed.), Henry Moore. Volume 4: Complete Sculpture 1964–73, London 1977, no.577, p.11 (?another cast reproduced pls.86–7).

1978

The Henry Moore Gift, exhibition catalogue, Tate Gallery, London 1978, reproduced p.61.

1981

Christa Lichtenstern, ‘Henry Moore and Surrealism’, Burlington Magazine, vol.123, no.944, November 1981, pp.644–58 (?another cast reproduced p.654).

1981

Richard Calvocoressi, ‘T.2302 Large Totem Head’, in The Tate Gallery 1978–80: Illustrated Catalogue of Acquisitions, London 1981, p.141, reproduced p.141.

2006

David Mitchinson (ed.), Celebrating Moore: Works from the Collection of the Henry Moore Foundation, London 2006, pp.287–8.

Technique and condition

This large bronze sculpture takes the form of an ovoid shell with a smooth rounded back and a concave front, marked down its centre by a vertical rib of bronze (fig.1). It is currently displayed outdoors in the Yorkshire Sculpture Park.

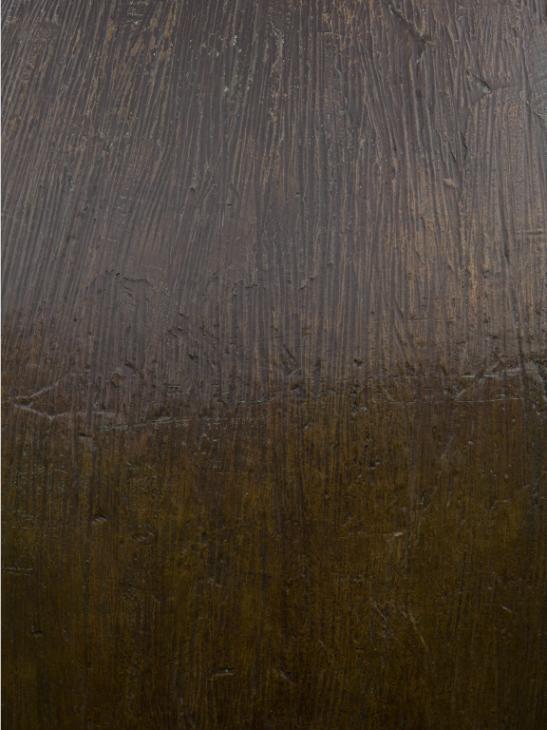

The bronze would have been cast from a mould taken from a plaster version of the sculpture, which Moore and his assistants made by building layers of wet plaster onto a supportive armature, probably constructed from wood or metal. The surface of the bronze replicates the surface of the plaster version, which was textured by Moore while it was still setting. For example, multiple striations can be seen running down the length of the sculpture, particularly on the back, which would have been created while the plaster was still soft (see fig.2).

Henry Moore

Large Totem Head 1968, cast date unknown

Tate T02302

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.1

Henry Moore

Large Totem Head 1968, cast date unknown

Tate T02302

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Detail of striations on back of Large Totem Head 1968, cast date unknown

Tate T02302

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.2

Detail of striations on back of Large Totem Head 1968, cast date unknown

Tate T02302

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

The completed plaster was then sent to a professional foundry, where a mould would have been taken into which molten bronze could be poured. Since bronze has to be cast in a single pour, the maximum size of any one piece of bronze is dependent on the size of the crucible used at the foundry. This means that it is often more practical and carries less risk to fabricate larger bronzes from a number of parts, which can then be welded together to form the whole. Two horizontal weld lines run around the sculpture indicating that it was cast in three more or less equally sized sections (fig.3). The welding seams were filed down and then textured using a range of small punch tools to integrate them with the surrounding surface.

After it had been cast, assembled and cleaned the sculpture was patinated using a range of chemical solutions that reacted with the bronze to produce coloured compounds. Potassium polysulphide was probably used to create the overall light brown colour of the sculpture, and ferric nitrate may have been applied to create warmer shades around the top and bottom of the sculpture, and inside the central cavity. A golden colour occupies the centre of the back where it curves prominently, achieved by applying a more transparent chemical patina. Slightly green areas can be seen around the lower back, which are most likely the result of weathering. In the past this sculpture was treated regularly with a lacquer coating, which served to protect the paler brown highlights and help prevent more of the patina from turning green. The sculpture is now cleaned annually as part of an ongoing maintenance programme, which involves removing dirt deposits and bird lime before a coating of wax is applied to protect it from environmental damage. The patina at the front of the sculpture towards the bottom has been worn away slightly, most likely caused by the sheep that graze in Yorkshire Sculpture Park. The sheep often shelter underneath the sculpture and their abrasive wool removes the patina from the surface where they rub against it.

Large Totem Head is mounted on a square base made of four bronze plates welded together. It features the artist’s signature on top and the foundry stamp below it on the side (fig.4). Outdoor sculptures like this are usually fixed into a concrete foundation underneath the base for extra stability.

Detail of welding seam on Large Totem Head 1968, cast date unknown

Tate T02302

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.3

Detail of welding seam on Large Totem Head 1968, cast date unknown

Tate T02302

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Detail of foundry stamp on base of Large Totem Head 1968, cast date unknown

Tate T02302

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.4

Detail of foundry stamp on base of Large Totem Head 1968, cast date unknown

Tate T02302

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Lyndsey Morgan

May 2013

How to cite

Lyndsey Morgan, 'Technique and Condition', May 2013, in Alice Correia, ‘Large Totem Head 1968, cast date unknown by Henry Moore OM, CH’, catalogue entry, September 2013, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015, https://wwwEntry

Henry Moore

Large Totem Head 1968, cast date unknown

Tate T02302

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.1

Henry Moore

Large Totem Head 1968, cast date unknown

Tate T02302

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore

Large Totem Head 1968, cast date unknown (rear view)

Tate T02302

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.2

Henry Moore

Large Totem Head 1968, cast date unknown (rear view)

Tate T02302

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Large Totem Head 1968, cast date unknown (side view)

Tate T02302

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.3

Large Totem Head 1968, cast date unknown (side view)

Tate T02302

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

From plaster to bronze

Henry Moore

Head: Boat Form 1963

Bronze

70 x 150 x 85 mm

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.4

Henry Moore

Head: Boat Form 1963

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

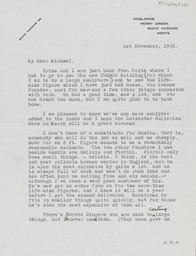

By the early 1960s Moore had established a practice of making small plaster models or maquettes to develop his sculptural ideas. In 1978 he explained:

I have gradually changed from using preliminary drawings for my sculptures to working from the beginning in three-dimensions. That is, I first make a maquette for any idea I have for a sculpture. The maquette is only three or four inches in size, and I can hold it in my hand, turning it over to look at it from above, underneath, and in fact from any angle.2

Plaster maquette for Head: Boat Form 1963

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Alice Correia

Fig.5

Plaster maquette for Head: Boat Form 1963

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Alice Correia

I look at them, handle them, see them from all round, and I may press them into clay and pour plaster into that clay and get a start as a bit of plaster, which is a reproduction of the object. And then add to it, change it. In that sort of way something turns out in the end that you could never have thought of the day before.4

It is possible that Head: Boat Form was produced by pressing a stone or bone into clay and pouring plaster into the depression it left. This piece of plaster would have then become the basis of the small maquette, which Moore could then model and add to how he wished. Head: Boat Form is one of many maquettes made over the course of Moore’s career that the artist chose to cast in bronze as a small table-top sculpture.

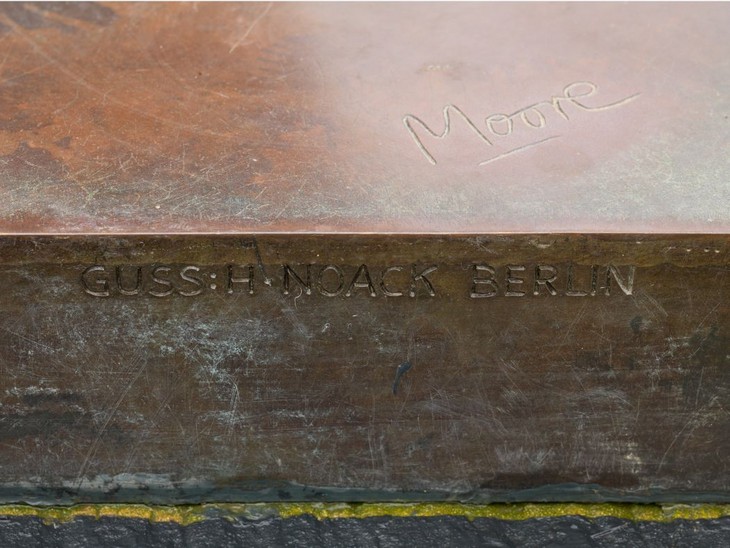

In 1968, having decided to enlarge Head: Boat Form, Moore set about creating an armature out of wood and possibly chicken wire, measured to the required size and shape of the larger sculpture based on the proportions of the maquette. The enlargement process was carried out in the plastic studio, a temporary structure erected in 1963 towards the back of the Hoglands estate, and was probably undertaken by Moore’s assistants because, as curator Julie Summers has noted, it was ‘a scientific rather than artistic process’.5 Once the armature had been constructed it was then draped in scrim, a bandage-like fabric, before successive layers of plaster were built up on top (fig.6). Moore would have taken over towards the end of this process to texture the surface of the plaster sculpture, which was replicated exactly in the bronze cast. The shallow parallel striations that feature on the upper areas of Large Totem Head were probably made using a cheese-grater (fig.7), while other textures may have been achieved using trowels and axes.

Full-size plaster version of Large Totem Head in the plastic studio at Hoglands 1968

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.6

Full-size plaster version of Large Totem Head in the plastic studio at Hoglands 1968

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Detail of striations on back of Large Totem Head 1968, cast date unknown

Tate T02302

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.7

Detail of striations on back of Large Totem Head 1968, cast date unknown

Tate T02302

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Detail of foundry stamp on base of Large Totem Head 1968, cast date unknown

Tate T02302

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.8

Detail of foundry stamp on base of Large Totem Head 1968, cast date unknown

Tate T02302

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

When the plaster was complete it was sent to the Noack Foundry in West Berlin to be cast in bronze. In 1967 Moore stated, ‘I use the Noack foundry for casting most of my work because in my opinion, Noack is the best bronze founder I know ... Also, the Noack foundry is reliable in all ways – in keeping to dates of delivery – and in sustaining the quality of their work’.6 Large Totem Head was cast in an edition of eight, but it is not known when Tate’s example was cast, and it is unclear whether the whole edition was cast at the same time or over a period of years. The top of the base is inscribed with Moore’s signature while the foundry mark ‘GUSS:H.NOACK BERLIN’ has been stamped on the side (fig.8).

It is not known whether the lost wax or sand casting technique was used to create this bronze sculpture, but in either case the technicians at Noack would have cut up the plaster sculpture into sections and taken moulds from each individual piece, into which molten bronze was poured. Once all the pieces of the sculpture had been cast they were welded together and the casting seams ‘chased’ to render the joins as imperceptible as possible. However, welding seams, such as those on the front of Large Totem Head, sometimes become more prominent over time if the metal used to weld the sections together has a different composition to the surrounding area of bronze (fig.9).

After it had been assembled at the foundry Moore would have inspected the quality of the casting and made decisions about its patination. A patina is the surface colour of a sculpture and is usually achieved by applying chemical solutions to the pre-heated bronze surface. In 1963 Moore maintained that ‘I always patinate bronze myself’, explaining that since he had conceived the sculpture it would be unlikely that anyone else would be able to replicate the exact colour he wanted.7 Moore usually patinated bronze sculptures at his studio, but during the 1960s and early 1970s he regularly travelled to the Noack Foundry and patinated his sculptures on their premises to avoid the expense of transporting works of this size. It is also known that, contrary to Moore’s claim, the technicians at Noack would sometimes patinate his sculptures following his instructions.

Tate’s cast of Large Totem Head has an overall warm red-brown patina, although darker brown shades can be seen at the top, bottom and in the interior cavity, while a golden-brown occupies the central curved section of the back (fig.10). Bronze is an alloy of copper and tin and prolonged exposure to chemicals in the air alters its patina. Slightly green areas, mainly located on the sculpture’s lower areas, were likely produced in this way.

Sources and contexts

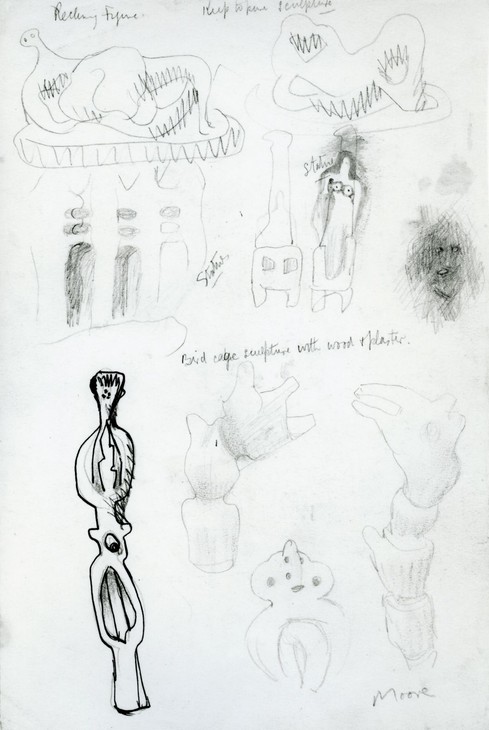

Henry Moore

Ideas for Sculpture 1935

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.11

Henry Moore

Ideas for Sculpture 1935

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Seen in light of these non-Western ethnographic sources it is possible to position Large Totem Head in relation to Moore’s engagement with ‘primitivism’, an over-arching term used by art historians to describe a tendency of early twentieth-century European modern art to emulate the forms and perceived values of non-Western art. The arts of so-called primitive cultures, which included tribal art from Africa, Asia and the Pacific Islands, as well as prehistoric and medieval European art, were deemed to be more authentic than the refined figurative art of the European classical tradition. Moore’s interest in ancient and non-Western art was cemented during the 1920s when he spent time examining the collections of the British Museum. In an interview given in 1932 Moore acknowledged his admiration for non-Western art, stating:

The primitive simplifies, I think, through directness of emotional aim to intensify their expression. Simplicity as an aim in itself tends to emptiness and monotony, but simplicity in carving, interpreted as lack of surface trimmings, reveals the contrast in section, axis, direction and bulk between different shapes and so intensifies the three-dimensional power in a work.11

The simplified shapes and bulky forms of Large Totem Head seem to correspond closely to Moore’s early understanding of so-called primitive sculpture. In 2006 Lichtenstern developed her analysis of Large Totem Head, suggesting that it possessed ‘an exotic monumentality’ reminiscent of a standing Easter Island figure.12 In this later essay Lichtenstern speculated that the sculpture may have also derived from ‘numerous Dogon masks originating from Western Sudan that were depicted in this [second] issue of Minotaure’.13 Lichtenstern described these masks as ‘being made up from two vertical indented rectangles which formed the oblong eyes; in between, a narrow vertical ridge marked the bridge of the nose’.14 This description suggests that Large Totem Head could be regarded as a schematically rendered face, an interpretation that seems to be supported by the work’s title. Furthermore, Tate researcher Richard Calvocoressi recorded that during a conversation with Moore in December 1980 the artist had described the sculpture as ‘evoking a huge impassive face with eyes.15

Henry Moore

Upright Internal/External Form 1952–3

Tate T02272

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.12

Henry Moore

Upright Internal/External Form 1952–3

Tate T02272

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Considering Large Totem Head in relation to Moore’s surrealist drawings of the 1930s, his experiments with internal and external forms in the 1950s, and Head: Boat Form from 1963, draws attention to Moore’s life-long interest in revisiting and developing his earlier preoccupations. In the 1930s Moore did not have the financial resources to produce bronze sculptures of the scale of Large Totem Head, but by 1968 had become wealthy enough to bring earlier ideas to their fullest conclusions.

The Henry Moore Gift

Large Totem Head 1968, cast date unknown, being installed on the lawn in front of the Tate Gallery, 1978

Tate T02302

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.13

Large Totem Head 1968, cast date unknown, being installed on the lawn in front of the Tate Gallery, 1978

Tate T02302

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

After the 1978 exhibition Tate decided that it should lend certain large-scale works from the Henry Moore Gift to regional galleries in the United Kingdom on a long-term basis.19 In January 1981 Large Totem Head was lent to the Cooper Art Gallery in Barnsley. Except for a four-month period in 1987 when the sculpture was exhibited at Yorkshire Sculpture Park in Wakefield, Large Totem Head remained at the Cooper Art Gallery until 1996. Since that date the sculpture has been on permanent display at the Yorkshire Sculpture Park.

Large Totem Head exists in an edition of eight plus one artist’s copy. In addition to Tate’s work, examples of the sculpture can be found in the collections of The Henry Moore Foundation, Perry Green; the City of Nuremberg; Musée des Beaux-Arts, Montreal; and the Donald J. Hall Sculpture Park at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas. Three casts are known to be held in private collections but the whereabouts of the remaining sculpture are unknown.

Alice Correia

September 2013

Notes

Henry Moore cited in Warren Forma, Five British Sculptors: Work and Talk, New York 1964, pp.67, 73, reprinted in Alan Wilkinson (ed.), Henry Moore: Writings and Conversations, Aldershot 2002, p.207.

John Read in Henry Moore: One Yorkshireman Looks at His World, dir. by John Read, television programme, broadcast BBC 2, 11 November 1967, http://www.bbc.co.uk/archive/henrymoore/8807.shtml , accessed 3 November 2013.

Henry Moore in ‘Henry Moore Talking to David Sylvester’, 7 June 1963, transcript of Third Programme, broadcast BBC Radio, 14 July 1963, p.18, Tate Archive TGA 200816. (An edited version of this interview was published in the Listener, 29 August 1963, pp.305–7.)

Julie Summers, ‘Fragment of Maquette for King and Queen’, in Claude Allemand-Cosneau, Manfred Fath and David Mitchinson (eds.), Henry Moore From the Inside Out: Plasters, Carvings and Drawings, Munich 1996, p.126. Between 1967 and 1968, when the enlargement process was probably undertaken, Moore’s assistants included Colin Barker, John Farnham, Ramy Shuklinsky, Richard Wentworth and Yeheskiel Yardini.

Moore was an avid reader of surrealist periodicals and during the 1930s his work was reproduced in Minotaure and the International Surrealist Bulletin. See Julia Kelly, ‘The Unfamiliar Figure: Henry Moore in French Periodicals of the 1930s’, in Jane Beckett and Fiona Russell (eds.), Henry Moore: Critical Essays, Aldershot 2003, pp.43–65.

Christa Lichtenstern, ‘Henry Moore and Surrealism’, Burlington Magazine, vol.123, no. 944, November 1981, p.657.

Henry Moore, ‘On Carving’, New English Weekly, 5 May 1932, pp.65–6, reprinted in Wilkinson 2002, p.190.

Christa Lichtenstern, ‘Large Totem Head’, in David Mitchinson (ed.), Celebrating Moore: Works from the Collection of the Henry Moore Foundation, London 2006, p.287.

Richard Calvocoressi, ‘T.2302 Large Totem Head’ in The Tate Gallery 1978–80: Illustrated Catalogue of Acquisitions, London 1981, p.141.

Related essays

- Scale at Any Size: Henry Moore and Scaling Up Rachel Wells

- Henry Moore: The Plasters Anita Feldman

- Henry Moore and World Sculpture Dawn Ades

- Henry Moore's Approach to Bronze Lyndsey Morgan and Rozemarijn van der Molen

Related catalogue entries

Related material

How to cite

Alice Correia, ‘Large Totem Head 1968, cast date unknown by Henry Moore OM, CH’, catalogue entry, September 2013, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015, https://www