Henry Moore OM, CH Helmet Head No.4: Interior-Exterior 1963, cast date unknown

Image 1 of 15

-

Henry Moore OM, CH, Helmet Head No.4: Interior-Exterior 1963, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Helmet Head No.4: Interior-Exterior 1963, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Helmet Head No.4: Interior-Exterior 1963, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Helmet Head No.4: Interior-Exterior 1963, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Helmet Head No.4: Interior-Exterior 1963, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Helmet Head No.4: Interior-Exterior 1963, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Helmet Head No.4: Interior-Exterior 1963, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Helmet Head No.4: Interior-Exterior 1963, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Helmet Head No.4: Interior-Exterior 1963, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Helmet Head No.4: Interior-Exterior 1963, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Helmet Head No.4: Interior-Exterior 1963, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Helmet Head No.4: Interior-Exterior 1963, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Helmet Head No.4: Interior-Exterior 1963, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Helmet Head No.4: Interior-Exterior 1963, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Helmet Head No.4: Interior-Exterior 1963, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Helmet Head No.4: Interior-Exterior 1963, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Helmet Head No.4: Interior-Exterior 1963, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Helmet Head No.4: Interior-Exterior 1963, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Helmet Head No.4: Interior-Exterior 1963, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Helmet Head No.4: Interior-Exterior 1963, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Helmet Head No.4: Interior-Exterior 1963, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Helmet Head No.4: Interior-Exterior 1963, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Helmet Head No.4: Interior-Exterior 1963, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Helmet Head No.4: Interior-Exterior 1963, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Helmet Head No.4: Interior-Exterior 1963, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Helmet Head No.4: Interior-Exterior 1963, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Helmet Head No.4: Interior-Exterior 1963, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Helmet Head No.4: Interior-Exterior 1963, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Helmet Head No.4: Interior-Exterior 1963, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Helmet Head No.4: Interior-Exterior 1963, cast date unknown© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH,

Helmet Head No.4: Interior-Exterior

1963, cast date unknown

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

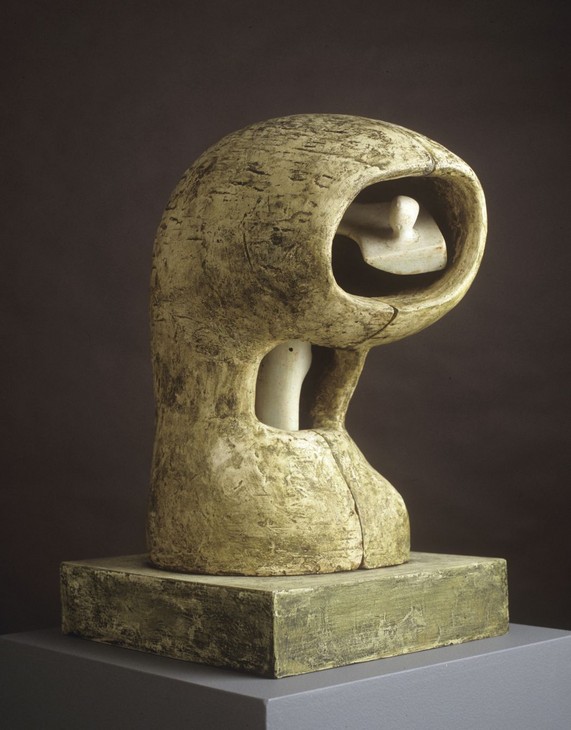

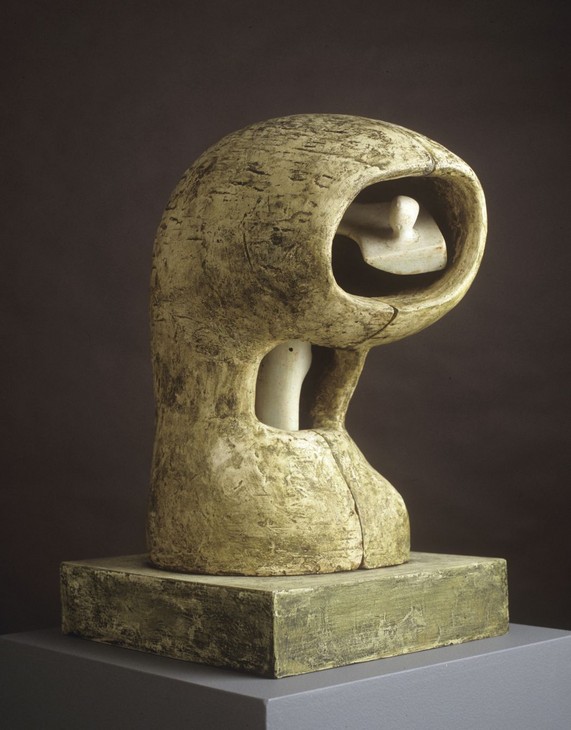

Helmet Head No.4: Interior-Exterior is one of the more ambiguous works in the series of ‘helmet head’ sculptures that preoccupied Moore throughout his career. Despite the militaristic connotations of its title, the outer form of the sculpture is less recognisable as a helmet than other works in the series, while the interior element, modelled on an animal bone, attests to Moore’s imaginative use of natural forms.

Henry Moore OM, CH 1898–1986

Helmet Head No.4: Interior-Exterior

1963, cast date unknown

Bronze

420 x 766 x 423 mm

Inscribed ‘Moore 0/6’ on rear and ‘Moore’ on base

Presented by the artist 1978

Artist’s copy aside from edition of 6 plus 1 artist’s copy

T02291

Helmet Head No.4: Interior-Exterior

1963, cast date unknown

Bronze

420 x 766 x 423 mm

Inscribed ‘Moore 0/6’ on rear and ‘Moore’ on base

Presented by the artist 1978

Artist’s copy aside from edition of 6 plus 1 artist’s copy

T02291

Ownership history

Presented by the artist to Tate in 1978 as part of the Henry Moore Gift.

Exhibition history

1965

British Sculpture in the Sixties: An Exhibition Organised by the Contemporary Art Society in Association with the Peter Stuyvesant Foundation, Tate Gallery, London, February–April 1965, no.80.

1968–9

Henry Moore, Rijksmuseum Kröller-Müller, Otterlo, May–July 1968; Museum Boymans-Van Beuningen, Rotterdam, September–November 1968, no.114.

1970

Henry Moore: Bronzes 1961–70, Marlborough Gallery, New York, April–May 1970 (?another cast exhibited no.13).

1971

Henry Moore, Musée Rodin, Paris, 1971, no.45.

1971

Henry Moore: Sculpture, Drawings, Graphics, Turnpike Gallery, Leigh, November–December 1971, no.14.

1972

Henry Moore, Playhouse Gallery, Harlow, March–April 1972, no.5.

1978

The Henry Moore Gift, Tate Gallery, London, June–August 1978, no number.

1998

Henry Moore 1898–1986, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, March–August 1998, no.38.

References

1965

Herbert Read, Henry Moore: A Study of His Life and Work, London 1965, pp.238–40, reproduced pl. 229.

1965

Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Marlborough Gallery, Rome 1965 (?another cast reproduced no.36).

1965

Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Marlborough Fine Art, London 1965 (?another cast reproduced no.16).

1967

Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto 1967 (another cast reproduced no.18).

1968

John Russell, Henry Moore, London 1968, p.193, reproduced pl.203.

1968

Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Rijksmuseum Kröller-Müller, Otterlo 1968, reproduced no.114.

1968

David Sylvester, Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Tate Gallery, London 1968.

1970

Robert Melville, Henry Moore: Sculpture and Drawings 1921–69, London 1970.

1970

Henry Moore: Bronzes 1961–70, exhibition catalogue, Marlborough Gallery, New York 1970 (?another cast reproduced p.50, no.13).

1975

John Russell, Henry Moore, revised edn, London 1975, pp.138–42, reproduced pl.131.

1978

The Henry Moore Gift, exhibition catalogue, Tate Gallery, London 1978, reproduced p.50.

1981

Richard Calvocoressi, ‘T.2291, Helmet Head No.4: Interior-Exterior 1963’ in The Tate Gallery 1978–80: Illustrated Catalogue of Acquisitions, London 1981, pp.132–3, reproduced p.132.

1982

Henry Moore: Head–Helmet, exhibition catalogue, DLI Museum and Arts Centre, Durham 1982 (another cast reproduced p.26, no.32).

1982

Henry Moore en México: Escultura, Dibujo, Grafica de 1921 a 1982, exhibition catalogue, Museo de Arte Moderno, Mexico City 1982 (another cast reproduced p.62, no.78).

1983

Henry Moore: Esculturas, Dibujos, Grabados – Obras de 1921 a 1982, exhibition catalogue, Museum of Contemporary Art, Caracas 1983 (another cast reproduced p.68, no.33).

1986

Alan Bowness (ed.), Henry Moore. Volume 3: Sculpture and Drawings 1955–64, 1965, revised edn, London 1986, no.508, pl.155.

1986

The Art of Henry Moore: Sculptures, Drawings and Graphics 1921–1984, exhibition catalogue, Metropolitan Art Museum, Tokyo 1986.

1993

Laura Doan, ‘Wombs of War: Henry Moore’s Repositioning of Gender’, Gender, no.17, fall 1993, pp.41–58.

1998

Henry Moore 1898–1986, exhibition catalogue, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna 1998, reproduced p.185.

1999

Patrick McCaughey, Henry Moore and the Heroic: A Centenary Tribute, exhibition catalogue, Yale Centre for British Art, New Haven 1999 (another cast reproduced).

2002

Henry Moore Rétrospective, exhibition catalogue, Fondation Maeght, Saint-Paul 2002 (another cast reproduced p.181, no.155).

2002–3

Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Musée des Beaux–Arts de Valenciennes, Valenciennes 2002 (another cast reproduced p.68, no.30).

2006

Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Fundació ‘la Caixa’, Barcelona 2006 (another cast reproduced p.159).

Technique and condition

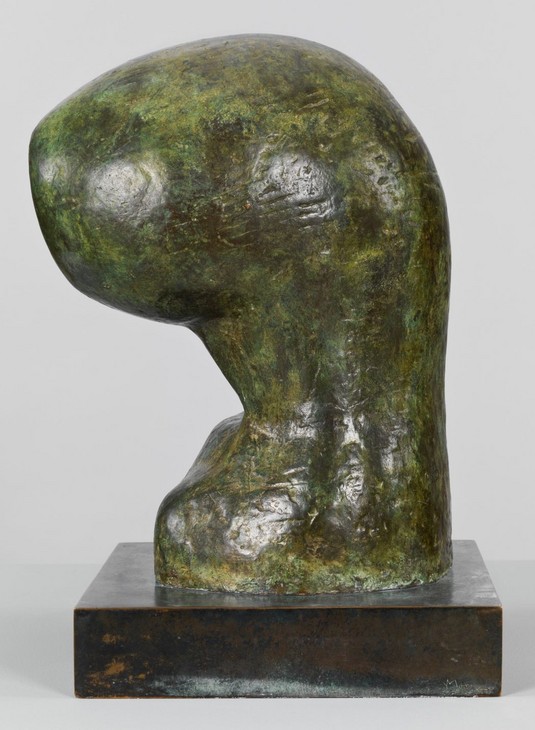

Helmet Head No.4: Interior-Exterior is a bronze sculpture in two parts, one of which is partially encased in the other. The external component is a mottled brown-green colour and takes the form of an upright tubular column that curves towards the front where a rounded opening reveals a brightly polished golden object inside. The sculpture is mounted on a square bronze base with a smooth surface coloured in mottled blacks, browns and greens. It has been fixed to this base from underneath using three threaded bolts.

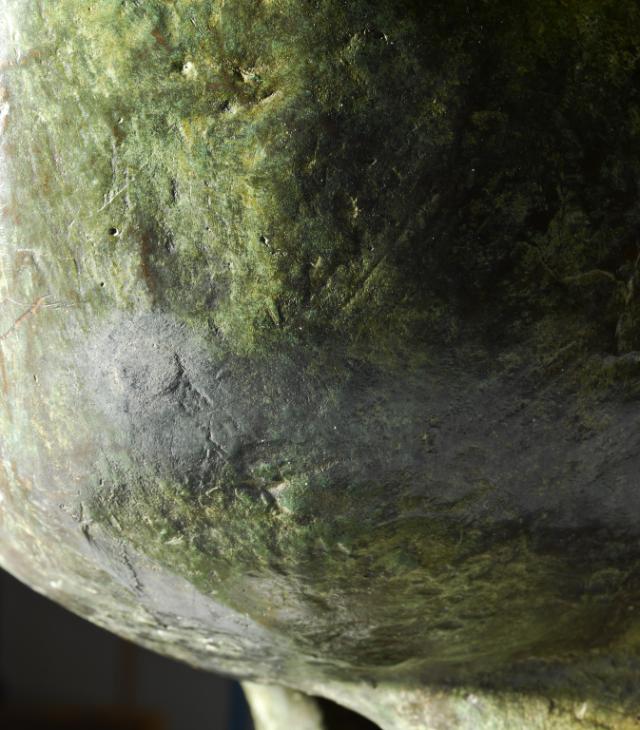

To create this sculpture Moore would have initially constructed a model in plaster by building up successive layers of wet plaster over a supportive armature, usually made out of wood, chicken wire and scrim (fig.1). The surface of the exterior form shows how Moore used a variety of techniques to create texture as he applied plaster to his model. For example, a number of straight horizontal impressions are visible on the rounded upper section of the sculpture (fig.2). When the plaster model was completed it was transported to the Art Bronze Foundry in London where a mould of the original would have been taken to cast the edition of seven bronzes plus two artist’s copies.

Henry Moore

Helmet Head No.4: Interior-Exterior 1963

Plaster

570 x 350 x 350 mm

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Michel Muller, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.1

Henry Moore

Helmet Head No.4: Interior-Exterior 1963

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Michel Muller, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Detail of surface texture on exterior form of Helmet Head No.4: Interior-Exterior 1963, cast date unknown

Tate T02291

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.2

Detail of surface texture on exterior form of Helmet Head No.4: Interior-Exterior 1963, cast date unknown

Tate T02291

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Detail of casting investment on Helmet Head No.4: Interior-Exterior 1963, cast date unknown

Tate T02291

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.3

Detail of casting investment on Helmet Head No.4: Interior-Exterior 1963, cast date unknown

Tate T02291

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

The inner piece is attached to the outer form at two points visible through the larger opening. It is attached by a small screw thread where its lower edge meets the lip of the opening (fig.4), and a brass weld can be seen where its rear corner meets the interior wall (fig.5). However, it is possible that the weld was a later repair.

Detail of fixing in Helmet Head No.4: Interior-Exterior 1963, cast date unknown

Tate T02291

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.4

Detail of fixing in Helmet Head No.4: Interior-Exterior 1963, cast date unknown

Tate T02291

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore

Helmet Head No.4: Interior-Exterior 1963, cast date unknown Detail of fixing

Tate T02291

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.5

Henry Moore

Helmet Head No.4: Interior-Exterior 1963, cast date unknown Detail of fixing

Tate T02291

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

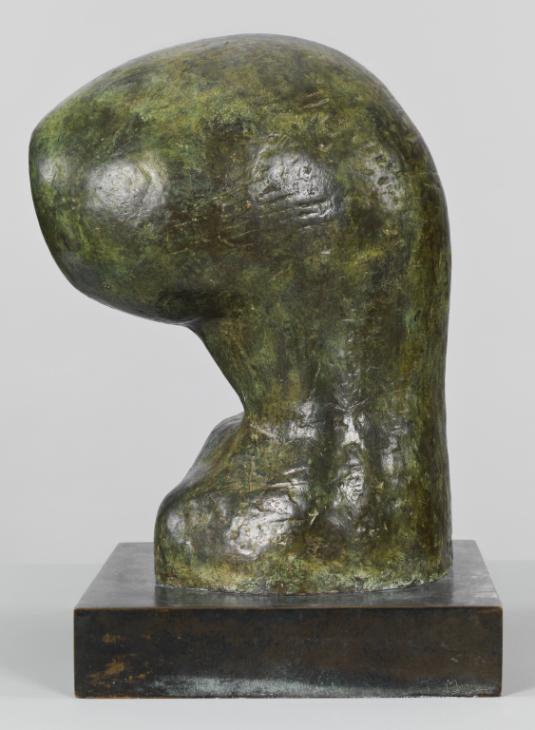

The outer bronze form was artificially patinated by applying chemical solutions to its surface which reacted with the bronze to produce coloured compounds (fig.6). The variegated green and brown finish would have been achieved using layers of different chemicals. First a chemical such as potassium polysulphide (or ‘liver of sulphur’) was applied, producing a layer of dark brown patina similar in colour to that of its interior surfaces. A more opaque green patina was then stippled onto the outer surfaces. Many different formulas can be used to produce green patinas but they usually contain mixtures of copper and ammonium salts dissolved in water. Green patinas are often relatively soft and fragile and so lend themselves to being rubbed back to reveal the underlying brown on the high points. In the case of this sculpture further depth of colour has been created by stippling a transparent chestnut brown patina over the green layer, possibly using a solution of ferric nitrate. After these layers were applied the surface was given a coating of wax for protection.

Henry Moore

Helmet Head No.4: Interior-Exterior 1963, cast date unknown (side view showing patination)

Tate T02291

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.6

Henry Moore

Helmet Head No.4: Interior-Exterior 1963, cast date unknown (side view showing patination)

Tate T02291

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Detail of brush marks on interior form of Helmet Head No.4: Interior-Exterior 1963, cast date unknown

Tate T02291

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.7

Detail of brush marks on interior form of Helmet Head No.4: Interior-Exterior 1963, cast date unknown

Tate T02291

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

The polished inner form has not been patinated but there are traces of lacquer visible as slight brush patterns on its surface (fig.7). The darker lines show where the lacquer has broken down in some areas, allowing oxidation to take place over time.

Detail of signature and edition number on Helmet Head No.4: Interior-Exterior 1963, cast date unknown

Tate T02291

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.8

Detail of signature and edition number on Helmet Head No.4: Interior-Exterior 1963, cast date unknown

Tate T02291

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore

Helmet Head No.4: Interior-Exterior 1963, cast date unknown Detail of base showing signature

Tate T02291

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.9

Henry Moore

Helmet Head No.4: Interior-Exterior 1963, cast date unknown Detail of base showing signature

Tate T02291

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

The sculpture is signed ‘Moore 0/6’ on the back close to where it meets the base (fig.8). A second signature, simply reading ‘Moore’, has been inscribed on the base in the bottom right-hand corner of the right-hand edge (fig.9).

Lyndsey Morgan

March 2013

How to cite

Lyndsey Morgan, 'Technique and Condition', March 2013, in Alice Correia, ‘Helmet Head No.4: Interior-Exterior 1963, cast date unknown by Henry Moore OM, CH’, catalogue entry, October 2013, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015, https://wwwEntry

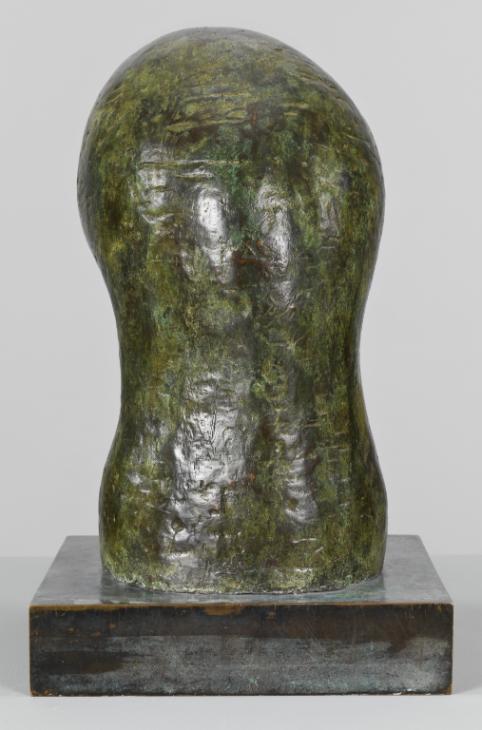

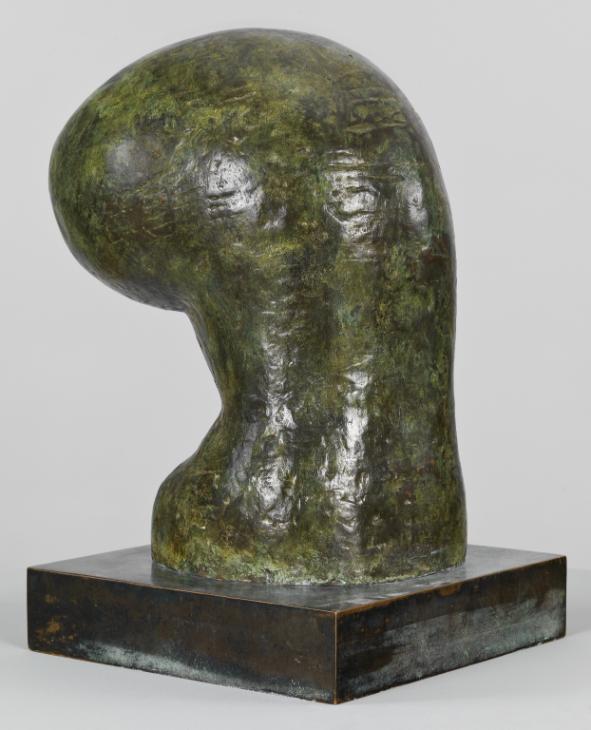

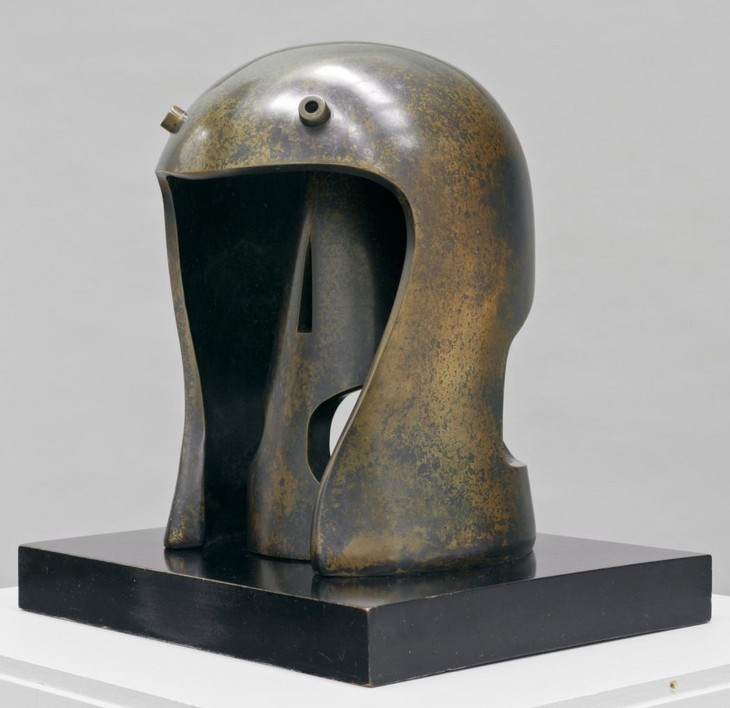

Helmet Head No.4: Interior-Exterior is one of a number of ‘helmet head’ sculptures made by Henry Moore between 1939 and 1986, all of which contain an indeterminate element enclosed within a hollow outer form. In the case of this sculpture, a shiny golden object can be seen occupying the interior of a green, telescope-like tubular form through rounded openings at the front. Although both elements are made of bronze, Moore has distinguished them as singular forms by using contrasting techniques to model and finish each one.

Henry Moore

Helmet Head No.4: Interior-Exterior 1963, cast date unknown (side view)

Tate T02291

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.1

Henry Moore

Helmet Head No.4: Interior-Exterior 1963, cast date unknown (side view)

Tate T02291

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Helmet Head No.4: Interior-Exterior 1963, cast date unknown (front view)

Tate T02291

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.2

Helmet Head No.4: Interior-Exterior 1963, cast date unknown (front view)

Tate T02291

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

The outer element takes the form of an upright tubular column, extending upwards from the bronze base before curving forwards at a right angle (fig.1). The form swells at this point making it appear top heavy, although it begins to narrow as it projects towards the front where it terminates abruptly in a rounded opening that reveals the interior to be hollow. Another opening has been made directly below it in the thinner, more upright section of the column, although this hole is smaller and more square-shaped (fig.2).

It is only through the two openings in the outer component that the interior element is visible. Tall, thin and formed of smoothed curves, it is positioned vertically inside the sculpture. At its apex, visible only through the upper-most hole, it appears to curl abruptly towards the opening, but closer inspection reveals that it consists of two separate interlocking elements (fig.3). The tall vertical piece has a groove in its upper edge, into which has been placed a flatter, horizontally orientated piece with angular edges and a spherical knob protruding from its upward-facing side. Both internal pieces are smooth and highly polished. They are golden in colour and, although they have not been artificially patinated, they have been coated in a protective lacquer. Evidence of this coating can be identified in streak marks left by the brush used to apply the lacquer. The upper, seemingly balanced piece is attached to the inside of the domed swelling at two discernable points, and looks to have been soldered.

Detail of brush marks on interior form of Helmet Head No.4: Interior-Exterior 1963, cast date unknown

Tate T02291

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.3

Detail of brush marks on interior form of Helmet Head No.4: Interior-Exterior 1963, cast date unknown

Tate T02291

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Detail of surface texture on exterior form of Helmet Head No.4: Interior-Exterior 1963, cast date unknown

Tate T02291

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.4

Detail of surface texture on exterior form of Helmet Head No.4: Interior-Exterior 1963, cast date unknown

Tate T02291

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

The surface of the exterior form has a slightly mottled and pitted texture, indicating the way in which plaster was applied to the model from which the bronze was cast. Moore has also incised short parallel lines into the outer surface of this form at irregular intervals, particularly at the domed top (fig.4). The exterior element has been artificially patinated and exhibits a range of mottled green hues across its surface.

From plaster to bronze

In order to create this bronze sculpture Moore would have first made a model of the work in plaster (fig.5). The internal and external elements would have been crafted separately. To make the exterior form Moore would have built up successive layers of plaster over an armature constructed from wood, or possibly chicken wire. Using an array of tools, including chisels, files and sandpaper, Moore could create different textures according to how wet or dry the plaster was. Moore found plaster to be a very useful material because it could be ‘both built up, as in modelling, or cut down, in the way you carve stone or wood’.1

Henry Moore

Helmet Head No.4: Interior-Exterior 1963

Plaster

570 x 350 x 350 mm

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Michel Muller, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.5

Henry Moore

Helmet Head No.4: Interior-Exterior 1963

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Michel Muller, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Animal bone with plaster additions from Henry Moore's studio

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Alice Correia

Fig.6

Animal bone with plaster additions from Henry Moore's studio

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Alice Correia

The vertical element of the interior piece was created by adding plaster to the leg bone of an animal (fig.6). Moore had collected pebbles, rocks and bones since the 1920s, and kept his ever growing ‘library of natural forms’ in his maquette studio, situated on the grounds of his home, Hoglands, in Perry Green, Hertfordshire.2 According to the filmmaker John Read, Moore liked to ‘shut himself away here, rummaging around, pondering and exploring’ the natural shapes of his collection of bones, shells and flint stones.3 Surrounded by these objects, Moore borrowed some of their formal features when it came to designing his own sculptures. In the case of the bone used for this sculpture, Moore added plaster to its base to stabilise it in an upright position, and more plaster to emphasise the rounded protrusion and recession of the socket and to model angular peaks at its apex. Once finished, Moore then made a plaster cast of the object allowing him to smooth and texture the entire surface freely.

When satisfied with the surface finish of each plaster element Moore sent them to a foundry to be cast in bronze. Although Helmet Head No.4: Interior-Exterior is not stamped with a foundry mark, records held at the Henry Moore Foundation note that Moore employed Remo Fiorini’s Art Bronze Foundry in London to produce the sculpture. The foundry had formerly traded under the name Fiorini Art Bronze Foundry, but in 1956 Remo Fiorini went into partnership with John Carney and the company changed its name. Moore had previously commissioned Fiorini to cast his Family Group 1948–9 (see Tate N06004) and, although the foundry had initially experienced problems casting large-scale works, Moore went on to use them throughout the 1950s and early 1960s. Moore’s Animal Head 1956 (Tate T02277) and Falling Warrior 1956–7 (Tate T02278) were also cast at Fiorini’s foundry.

A white residue visible on the interior surface of the telescopic form can be identified as casting investment (fig.7), suggesting that the sculpture was cast using the lost wax technique. The original plaster of the exterior piece has been cut vertically in half, suggesting that the foundry cast this component in two sections. The lost wax technique would have required the foundry to create a mould of each part, which would then be ‘greased’ with a releasing agent. Molten wax would then be poured into it and, once it had hardened, released from the mould as a wax replica of the original plaster. This wax replica would then be encased in a hard refractory material, placed in a kiln and heated. Channels within the casing would allow the melted wax to drain away and, once empty, the cavity would have been filled with molten bronze. In order to achieve an even and flawless cast all of the molten bronze had to be poured in one go. Once the bronze had cooled and hardened, the casing was removed, revealing the sculpture.4

Detail of casting investment on Helmet Head No.4: Interior-Exterior 1963, cast date unknown

Tate T02291

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.7

Detail of casting investment on Helmet Head No.4: Interior-Exterior 1963, cast date unknown

Tate T02291

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Helmet Head No.4: Interior-Exterior 1963, cast date unknown (side view showing patination)

Tate T02291

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.8

Helmet Head No.4: Interior-Exterior 1963, cast date unknown (side view showing patination)

Tate T02291

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

After casting, the bronze elements were probably returned to Moore so that he could inspect their quality and make decisions about their surface finish. The reflective surfaces of the interior forms were achieved by applying abrasives and polishing them, and their golden colour is that of the natural bronze. Although the outer surfaces of the exterior form have been cleaned to remove casting residues, there is little evidence to suggest that these surfaces were filed or chased after casting. The exterior piece, however, has been artificially patinated to produce a mottled green colour (fig.8). A patina is the surface colour of a sculpture and is usually achieved by applying chemical solutions to the pre-heated bronze surface. In 1963, the year Helmet Head No.4: Interior-Exterior was made, Moore asserted, ‘I always patinate bronze myself’, explaining that since he alone had conceived the sculpture it was unlikely that anyone else would be able to replicate the exact colour he wanted.5 When it came to assembling the separate elements of the sculpture it is likely that the vertical interior piece was slotted inside a hole at the base of the exterior form before the upper, horizontal section of the interior piece was soldered securely to the domed interior.

Sources and development

During his career Moore made a number of ‘helmet head’ sculptures exploring the relationship between interior and exterior forms. On 12 December 1980 Moore remarked to Richard Calvocoressi, then a research assistant at Tate, that the interior element of this work was hidden and protected from the light by the larger exterior piece, giving the sculpture an air of mystery.6 Discussing the helmet head series more generally that same year, Moore recalled that ‘the idea of one form inside another form may owe some of its incipient beginnings to my interest at one stage when I discovered armour. I spent many hours in the Wallace Collection, in London, looking at armour’.7 When he visited the Wallace Collection as a student in the 1920s Moore would have had access to one of the largest collections of armoury in Britain, including items dating back to the fourteenth century. However, in the late 1960s Moore also suggested that his interest was sparked by the artist ‘Wyndham Lewis talking about the shell of lobster covering the soft flesh inside’.8 The helmet head sculptures have also been associated with the image of a foetus in a womb, rendering them even harder to categorise, as the art historian Julian Stallabrass acknowledged in 1990:

The Helmet Heads and many of the associated pieces do not fit in comfortably with the rest of Moore’s work. They retain a masculine character despite the foetal and mother and child associations that are often made. They make specific references to some of the concerns of French thought, if not directly to Surrealism. They have a very definite relation to the war. This has made their assimilation into the Moore canon difficult, for so much of his work seems to be concerned with the feminine, with eternal human values, and to evade any specific categorization or debate.9

Henry Moore

Drawing for Metal Sculpture: Two Heads 1939

Charcoal, wash, pen and ink on paper

277 x 381 mm

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.9

Henry Moore

Drawing for Metal Sculpture: Two Heads 1939

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Moore’s first three-dimensional work to infer the form of a helmet and combine interior and exterior forms was The Helmet 1939–40 (fig.10). This lead sculpture was one of the last three-dimensional works produced by Moore before a lack of available resources halted his sculptural practice in 1940.12 For this work Moore enclosed a form made up of arches and ellipses, which may bear analogy to a standing figure within a domed shelter. Although art historians including Will Grohmann and Chris Stephens have interpreted the helmet head series through the lens of the Second World War, The Helmet may also be viewed in light of Moore’s interest in the ‘Mother and Child’ motif.13 In 1967 Moore acknowledged that the compositional arrangement of The Helmet related to ‘the Mother and Child where the outer form, the mother, is protecting the inner form, the child’.14 Furthermore, the German psychologist Erich Neumann argued in 1959 that The Helmet is ‘dominated by the mother-child symbolism: it forms a uterine shell within which there dwells a child inhabitant’.15

Although the Second World War curtailed Moore’s experiments in three dimensions, as the curator Ian Dejardin has asserted, ‘the helmet idea was too powerful not to re-emerge’, and in 1950 Moore made Helmet Head No.1 (fig.11).16 Discussing Moore’s sculptures of the 1950s, the critic John Russell acknowledged that their militaristic connotations are immediately recognisable, but also suggested that:

the implications of the Helmet pieces are a good deal more complex. It is uncertain for instance, whether the internal figure is protected or imprisoned by the helmet itself: whether it has, in short, got into a situation which it can no longer control. From the way in which this idea went on battering for Moore’s attention until well into the 1960s we can assume that it has a particular significance for him.17

Henry Moore

The Helmet 1939–40

Lead

Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.10

Henry Moore

The Helmet 1939–40

Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore

Helmet Head No.1 1950, cast 1960

Tate T00388

Photo © The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.11

Henry Moore

Helmet Head No.1 1950, cast 1960

Tate T00388

Photo © The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

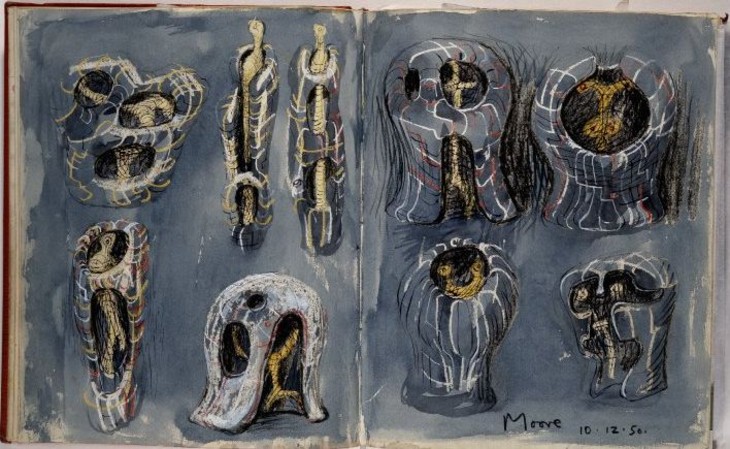

Henry Moore

Studies for Helmets and Full-Length Enclosed Figures 1950

Watercolour, pen and black ink and wax crayons over graphite on paper

251 x 402 mm

British Museum, London

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.12

Henry Moore

Studies for Helmets and Full-Length Enclosed Figures 1950

British Museum, London

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore

Head: Cyclops 1963

Bronze

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.13

Henry Moore

Head: Cyclops 1963

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

The art historian and long-time supporter of Moore’s work Kenneth Clark regarded the drawn and sculpted helmet heads as forming a powerful body of work which suggested that ‘in the back of Moore’s mind was the memory of those metal helmets worn by soldiers in a dictator’s army intent on quelling a revolt’.19 For Clark the helmet heads were daunting and disturbing objects, the most frightening of all being ‘the nameless bronze monsters of the 1960s. The most terrifying was cast in 1963’.20 Clark does not explicitly name this sculpture but it may have been Helmet Head No.4: Interior-Exterior. In an extended discussion of the varying representation of the head across Moore’s oeuvre Clark concluded that ‘Moore’s inner demon sees the human head as a terrible and fascinating enemy’.21

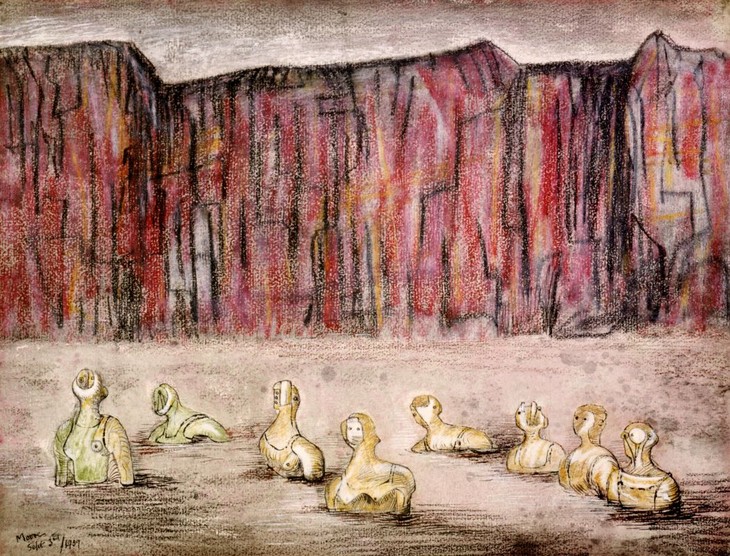

Henry Moore

September 3rd 1939 1939

Graphite, wax crayon, chalk, watercolour, pen and ink on paper

306 x 398 mm

The Moore Danowski Trust (The Henry Moore Family collection)

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.14

Henry Moore

September 3rd 1939 1939

The Moore Danowski Trust (The Henry Moore Family collection)

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Critical reception

A cast of Helmet Head No.4: Interior-Exterior was shown at Marlborough Fine Art’s New London Gallery in July 1965 as part of a two-person exhibition of works by Moore and the painter Francis Bacon. Reviewing this show in the Times under the title ‘Bacon and Moore Again in Powerful Relation’, an unnamed critic stated that the ‘the art of Mr Moore continues in its pace of unhurried majesty’.25 The term ‘majesty’ was also used by the critic G.S. Whittet, who wrote in the art magazine Studio International that he was struck by ‘the strength of his imagery and his full majesty of those forms that create presences of themselves’.26 Although Whittet did not mention Helmet Head No.4: Interior-Exterior by name, he may have been thinking of this sculpture when he wrote that ‘it is no exaggeration to say that in twentieth century art Henry Moore is the one who expresses, if not the goodness, at least the strength and dignity that survive in this civilisation’.27 The theme of survival was also noted in curator Bryan Robertson’s review of the exhibition. He noted that ‘Moore’s invincible sense of human resilience ... is sometimes frozen into hard, wary monumentality ... but his surrealist instinct makes it hard to tell hot from cold, flesh from bone, helmet or shell from leathery skin’.28

When examples from the helmet head series were included in Moore’s 1968 exhibition at Tate, however, the curator David Sylvester chose not to emphasise the militaristic or de-humanised aspects of the work. Instead Sylvester identified the relationship between the internal and external forms in these works as a manifestation of the mother and child relationship. For Sylvester the helmet head series belonged to the same class or family of works as Moore’s Reclining Mother and Child 1960–1 (Walker Art Centre, Minneapolis), in which the artist explored the complex nature of this relationship.29

Henry Moore

Superior Eye 1974–5, from Helmet Head Lithographs 1974–5

Lithograph on paper

311 x 318 mm

Tate P02266

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.15

Henry Moore

Superior Eye 1974–5, from Helmet Head Lithographs 1974–5

Tate P02266

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

The Henry Moore Gift

Helmet Head No.4: Interior-Exterior was presented by Henry Moore to the Tate Gallery in 1978 as part of the Henry Moore Gift, which comprised thirty-six sculptures including examples of the artist’s work in bronze, marble and plaster. Moore had initiated discussions about a major gift to the Tate in the early 1960s and signed a deed of agreement in June 1969.31 This agreement outlined the terms of the Henry Moore Gift and the works to be included in it. Moore did not stipulate that the works had to be on display permanently, or that a certain number of them had to be exhibited at any one time, but the agreement did state that the Gift was subject to Tate increasing the overall size of its gallery space. It also granted Moore permission to swap or exchange works on the agreed list with the approval of the Trustees, and that the Gift would remain in Moore’s possession for his lifetime, should he so choose.

In 1977 Tate’s director Norman Reid petitioned Moore to present his Gift so that it could be displayed in its entirety alongside the Tate’s existing collection of his work in an exhibition celebrating the artist’s eightieth birthday scheduled for the following year. Moore duly agreed and the Gift was delivered to the Tate in June 1978. A press release was duly prepared announcing that ‘The group [of sculptures] is the most substantial gift of works ever given to the Tate by an artist during his lifetime’.32 At the close of the exhibition in August 1978 Norman Reid reflected in a letter to Moore’s daughter Mary Danowski that although he was sad to see the exhibition close ‘we have the consolation of the splendid group of sculptures which Henry has presented to the nation’.33

Helmet Head No.4: Interior–Exterior is numbered 508 in the artist’s catalogue raisonné and was cast in bronze in an edition of six, plus two artist’s copies.34 In addition to Tate’s example, versions of the sculpture can be found in the collections of the Henry Moore Foundation and the Everson Museum of Art of Syracuse, New York. Other casts are believed to be held in private collections. The original plaster from which the bronze edition was cast is also held at the Henry Moore Foundation.

Alice Correia

October 2013

Notes

Henry Moore: One Yorkshireman Looks at His World, dir. by John Read, BBC television programme, first broadcast on BBC2, 11 November 1967, http://www.bbc.co.uk/archive/henrymoore/8807.shtml , accessed 3 November 2013.

For an explanatory video on the lost wax casting technique see http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/articles/s/sculpture-techniques/ , accessed 17 October 2013.

Henry Moore cited in David Sylvester, Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Tate Gallery, London 1968, pp.3–4.

See Richard Calvocoressi, ‘T.2291, Helmet Head No.4: Interior-Exterior 1963’, in The Tate Gallery 1978–80: Illustrated Catalogue of Acquisitions, London 1981, p.133.

Henry Moore in conversation with David Mitchinson, 1980, transcript reproduced in Alan Wilkinson (ed.), Henry Moore: Writings and Conversations, Aldershot 2002, p.213.

Henry Moore cited in Michael Chase, ‘Moore on his Methods’, Christian Science Monitor, 24 March 1967, reprinted in Wilkinson 2002, p.214.

Julian Stallabrass, ‘Darkness in the Shelter’, in Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Museo de Bellas Artes de Bilbao, Bilbao 1990. Text published in Basque and Spanish. For English version see http://www.courtauld.ac.uk/people/stallabrass_julian/PDF/Bilbao.pdf , accessed 22 October 2013.

See Will Grohmann, The Art of Henry Moore, London 1960, and Chris Stephens (ed.), Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Tate Britain, London 2010.

Ian Dejardin, ‘Square Forms and Heads’, in Henry Moore at Dulwich Picture Gallery, exhibition catalogue, Dulwich Picture Gallery, London 2004, pp.97–8.

Julian Andrews, ‘Helmet Head No.1’, in David Mitchinson (ed.), Celebrating Moore: Works from the Collection of the Henry Moore Foundation, London 2006, p.226.

G.S. Whittet, ‘Farewell to Flat, Goodbye to Square: London Commentary’, Studio International, October 1965, p.169.

For Reclining Mother and Child 1960–1 see http://www.walkerart.org/collections/artworks/reclining-mother-and-child , accessed 31 October 2013.

Related essays

- ‘A stimulation to greater effort of living’: The Importance of Henry Moore’s ‘credible compromise’ to Herbert Read’s Aesthetics and Politics Ben Cranfield

- Erich Neumann on Henry Moore: Public Sculpture and the Collective Unconscious Tim Martin

- Henry Moore's Approach to Bronze Lyndsey Morgan and Rozemarijn van der Molen

Related catalogue entries

How to cite

Alice Correia, ‘Helmet Head No.4: Interior-Exterior 1963, cast date unknown by Henry Moore OM, CH’, catalogue entry, October 2013, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015, https://www