Henry Moore OM, CH Figure 1931

Image 1 of 11

-

Henry Moore OM, CH, Figure 1931© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Figure 1931© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Figure 1931© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Figure 1931© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Figure 1931© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Figure 1931© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Figure 1931© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Figure 1931© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Figure 1931© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Figure 1931© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Figure 1931© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Figure 1931© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Figure 1931© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Figure 1931© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Figure 1931© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Figure 1931© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Figure 1931© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Figure 1931© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Figure 1931© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Figure 1931© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved -

Henry Moore OM, CH, Figure 1931© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH, Figure 1931© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore OM, CH,

Figure

1931

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Moore’s use of rounded shapes and contours for Figure 1931 exemplifies his interest in developing a sculptural language inspired by the shapes of weathered stones and other natural materials. The sculpture also seems to reflect his knowledge of the work of Picasso and British-based contemporaries such as Epstein and Underwood.

Henry Moore OM, CH 1898–1986

Figure

1931

Beech on a beech base

248 x 178 x 121 mm

Bequeathed by E.C. Gregory 1959

T00240

Figure

1931

Beech on a beech base

248 x 178 x 121 mm

Bequeathed by E.C. Gregory 1959

T00240

Ownership history

Purchased from the artist through the Leicester Galleries by Sir Michael Sadler, Oxford, in 1933; purchased through the Leicester Galleries, London, in 1944 by E.C. Gregory, London, by whom bequeathed to Tate in 1959.

Exhibition history

1933

?Exhibition of Recent Paintings by English, French and German Artists, Mayor Gallery, London, 1933, either no.43 or no.44.

1933

Sculpture and Drawings by Henry Moore, Leicester Galleries, London, November 1933, either no.4 or no.19 (as ‘Composition’).

1944

Selected Paintings, Drawings and Sculpture from the Collection of the late Sir Michael Sadler, Leicester Galleries, London, January–February 1944.

1946

Henry Moore, Museum of Modern Art, New York, December 1946–March 1947; Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, April–May 1947; San Francisco Museum of Art, San Francisco, July–August 1947, no.18.

1947–8

Exhibition of Sculpture and Drawings by Henry Moore, British Council touring exhibition: Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney; Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery, Hobart; National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne; Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide; Art Gallery of Western Australia, Perth, 1947–8, no.10.

1949

Henry Moore: Sculpture and Drawings 1923–1948, Wakefield City Art Gallery, Wakefield, April–May 1949, Manchester City Art Gallery, Manchester, June–July 1949, no.23.

1949

Tentoonstelling Henry Moore: Beeldhouwwerken, Tekeningen, Palais des Beaux-Arts, Brussels, October 1949, no.17 (lender given as Douglas Glass).

1949–50

Henry Moore, British Council touring exhibition: Palais des Beaux-Arts, Brussels, October 1949; Musée d’art moderne, Paris, December 1949; Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, January 1950; Hamburger Kunsthalle, Hamburg, March 1950; Städtische Kunstsammlungen, Düsseldorf, May 1950; Kunsthalle Berne, Berne, June–July 1950, no.17.

1951

Sculpture and Drawings by Henry Moore, Tate Gallery, London, May–July 1951, no.84.

1952

Seventeen Collectors, Contemporary Art Society, London, May–June 1952, no.72 (as ‘Beechwood Figure’).

1978

The Henry Moore Gift, Tate Gallery, London, June–August 1978, no number.

1983

Henry Moore: 60 Years of his Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, May–September 1983, no number.

1984–5

Henry Moore: Sculpture in the Making, Leeds City Art Gallery, Leeds, November 1984–January 1985, no.5.

2009

Henry Moore, Barbara Hepworth, Ben Nicholson in the 1930s: A Nest of Gentle Artists, Norwich Castle Museum, Norwich, January–April 2009; Graves Gallery, Sheffield, May–August 2009, no.15.

References

1934

Herbert Read, Henry Moore: Sculptor, London 1934, reproduced pl.21 and dust jacket.

1944

Herbert Read (ed.), Henry Moore: Sculpture and Drawings, London 1944, reproduced pl.76.

1957

David Sylvester (ed.), Henry Moore. Volume 1: Complete Sculpture 1921–48, London 1957, no.111, reproduced p.67.

1960

Report of the Trustees for the Year 1 April 1959 to 31 March 1960, Tate Gallery, London 1960, p.23.

1965

Herbert Read, Henry Moore: A Study of his Life and Work, London 1965, reproduced pl.87.

1973

John Russell, Henry Moore, London 1973, reproduced p.53.

1982

Penny Sparke, Ettore Sottsass Jnr., London 1982, pp.10–11, reproduced.

1984

Henry Moore: Sculpture in the Making, exhibition catalogue, Leeds City Art Gallery, Leeds 1984, reproduced fig.15.

2009

Henry Moore, Barbara Hepworth, Ben Nicholson in the 1930s: A Nest of Gentle Artists, exhibition catalogue, Norwich Castle Museum, Norwich 2009.

Technique and condition

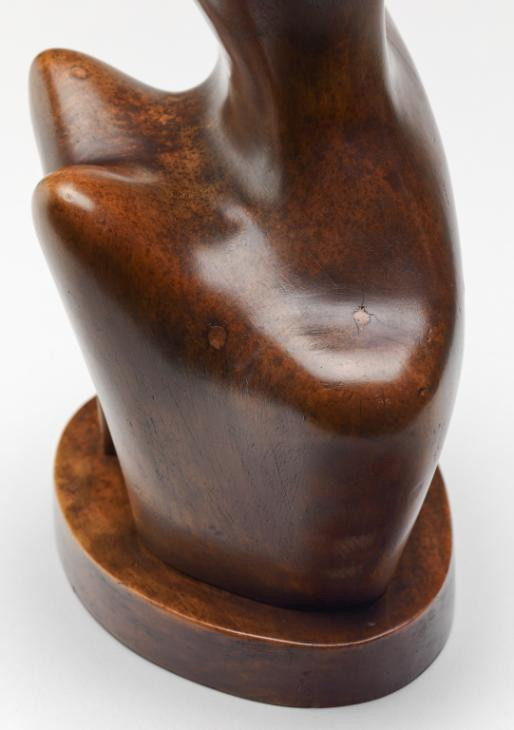

Detail of shoulder of Figure 1931 showing filled holes

Tate T00240

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.1

Detail of shoulder of Figure 1931 showing filled holes

Tate T00240

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

This work was the second sculpture Henry Moore made using beech wood. He would have carved out the shape using wood chisels with or without a mallet (a hammer with a large wooden head), refining the shape with rasps and finally sanding the surface with sandpaper. The inner part of the recessed belly has been sharply defined with a pointed chisel. The surface is mostly smooth, although tool marks, possibly from rasps, are visible on the inside of the arch. Three small holes have been filled, work that may date back to the making of the piece (fig.1).

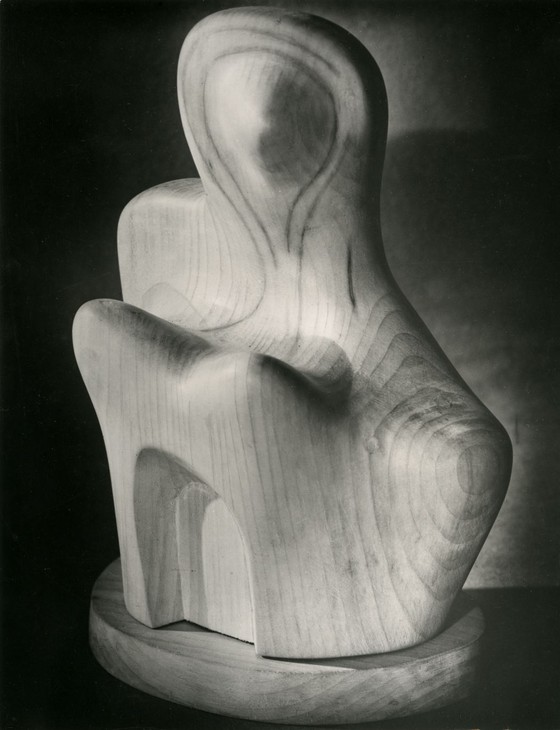

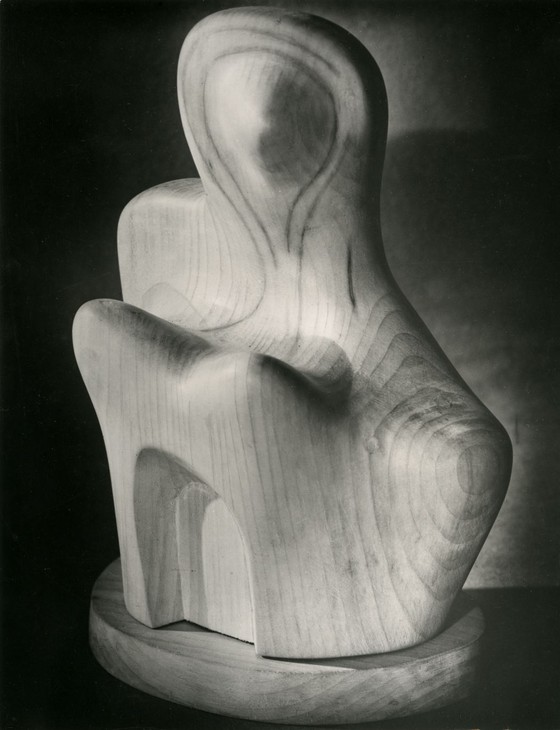

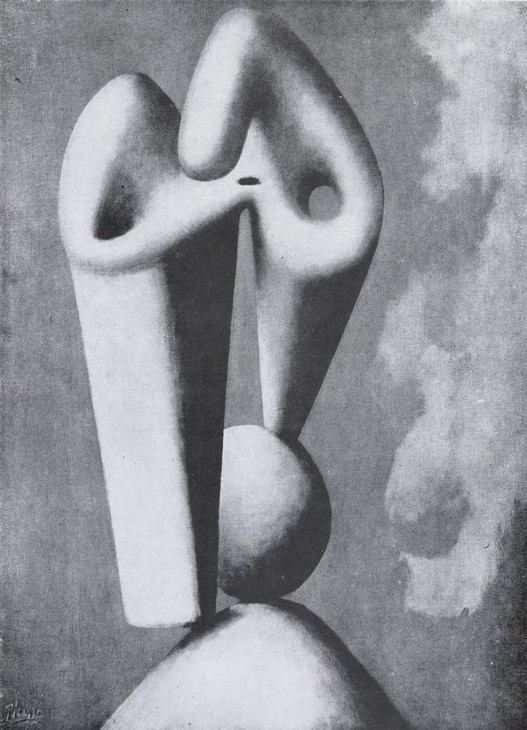

Photograph of Figure 1931 taken in c.1931–4, reproduced in Herbert Read, Henry Moore: Sculptor, An Appreciation, London 1934, pl.21

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.2

Photograph of Figure 1931 taken in c.1931–4, reproduced in Herbert Read, Henry Moore: Sculptor, An Appreciation, London 1934, pl.21

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

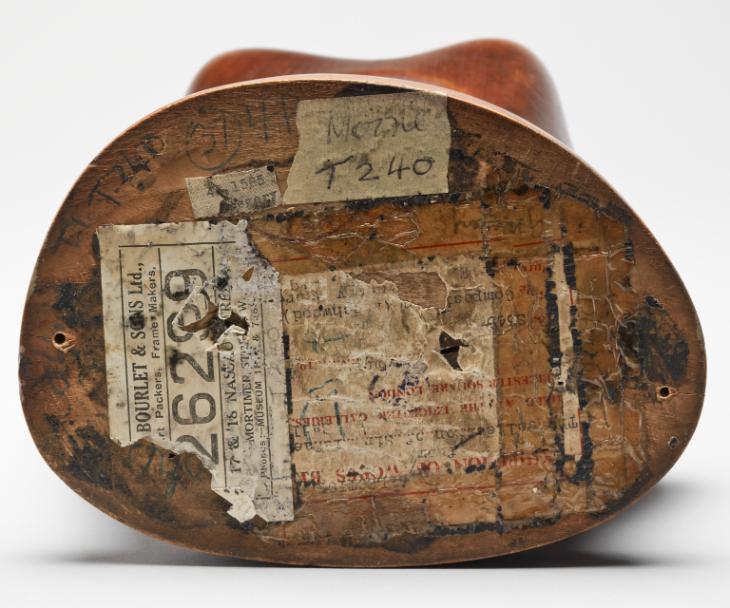

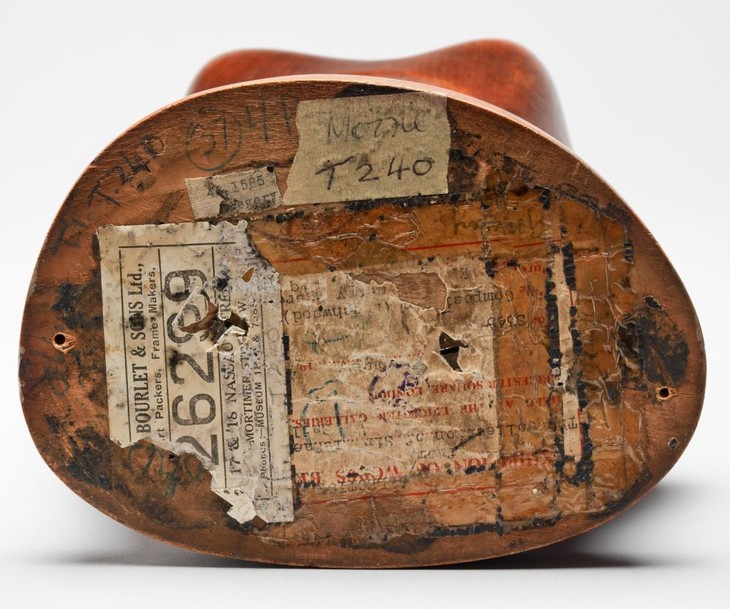

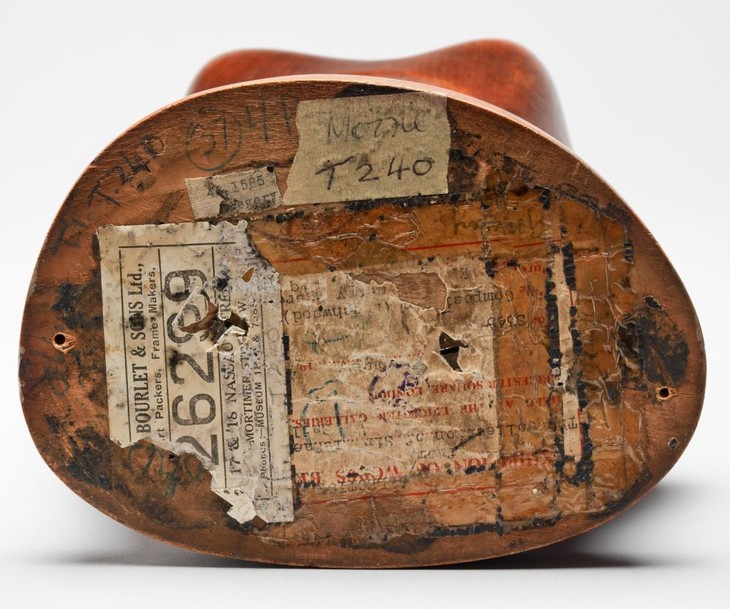

Detail of underside of base of Figure 1931

Tate T00240

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.3

Detail of underside of base of Figure 1931

Tate T00240

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

The shape of the head follows the pattern of the wood grain, which early photographs indicate was initially much more visible (fig.2). The wood has darkened over time and a protective layer of wax that was applied to the surface of the sculpture has also deepened in colour.

The torso is fixed to an oval base with screws (fig.3).

Rozemarijn van der Molen

February 2013

How to cite

Rozemarijn van der Molen, 'Technique and Condition', February 2013, in Alice Correia, ‘Figure 1931 by Henry Moore OM, CH’, catalogue entry, January 2013, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015, https://wwwEntry

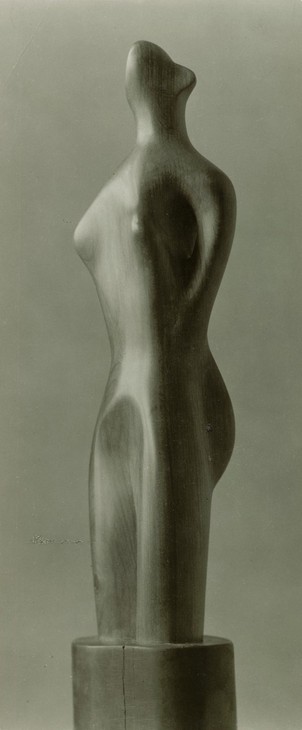

Figure is a small sculpture in dark, auburn-coloured beech wood presented on an oval base. It represents a female head and torso, cut at the waist, with a conical protrusion where facial features would usually be expected. Seen from the side, the head and neck appear to be straining forward, which emphasises the concave area of the chest. In front of this hollowed space are two upward pointing breasts, which appear to have swelled from below, but which could also be construed as knees drawn up to the chest.1 The tip of each one points in opposing directions creating a v-shaped cleavage between them. Below is a recessed arched cavity akin to a doorway. There are no incisions on the surface of the sculpture, which is uniformly smooth and polished, but there are a few cracks in the surface of the wood, and three round holes have been filled on the front of the sculpture.

Henry and Irina Moore in the studio at 11a Parkhill Road, London, 1932

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.1

Henry and Irina Moore in the studio at 11a Parkhill Road, London, 1932

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Henry Moore

Figure 1930

Beech

Private collection

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.2

Henry Moore

Figure 1930

Private collection

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Although the location and circumstances in which Figure was carved are unconfirmed, it is likely that it was created at Moore’s studio at 11a Parkhill Road in Hampstead, London. A photograph taken in 1932 of Moore and his wife Irina in this studio shows the completed Figure on a four-legged stool in the mirror, to the left of Irina’s reflection (fig.1).

Moore carved the sculpture in beech, a hard and close-grained wood, which is best carved when it is freshly cut (when it is green) as it hardens over time. The beech tree is indigenous to Britain, so Moore would have had little difficulty acquiring a block for carving, although prior to Figure he had only carved one other sculpture in beech, Figure 1930 (fig.2). In 1983 Moore reflected on the properties of the wood:

Beechwood [sic] is a silky kind of wood – you can give it a silky finish. It has a grain which is obvious, with a kind of undulating rhythm – upwards and downwards. It may have dark lines or lines that are hardly noticeable. The grain doesn’t show as much in beechwood [sic] as it does, say, in elm, but it is a close-grain wood and, therefore you can do small sculptures in it. The wood is suitable for carving and presents no special problems.2

Moore’s awareness of the grain and specific physical qualities of beech is significant because Figure was made using the technique of direct carving. This meant that Moore worked directly on the wood, using a range of gouges (a curved tool) without the aid of preparatory sketches or maquettes (scale models made in clay or plaster). Moore and his contemporaries, including the sculptors Barbara Hepworth and John Skeaping, believed that when carving directly into stone or wood to create a unique artwork, the form or shape of the final sculpture should evolve through the processes of its making, as the artist responds to the texture, graining and colour of the material under hand. The method of direct carving incorporated the doctrine of ‘truth to materials’. In 1934 Moore articulated what this principle meant to him: ‘Truth to Materials: Every material has its own individual qualities. It is only when the sculptor works direct, when there is an active relationship with his material that the material can take its part in the shaping of an idea’.3 Similarly, the art critic Herbert Read explained, ‘every work of art is a coalition of idea and material; success depends on finding a perfect balance’.4

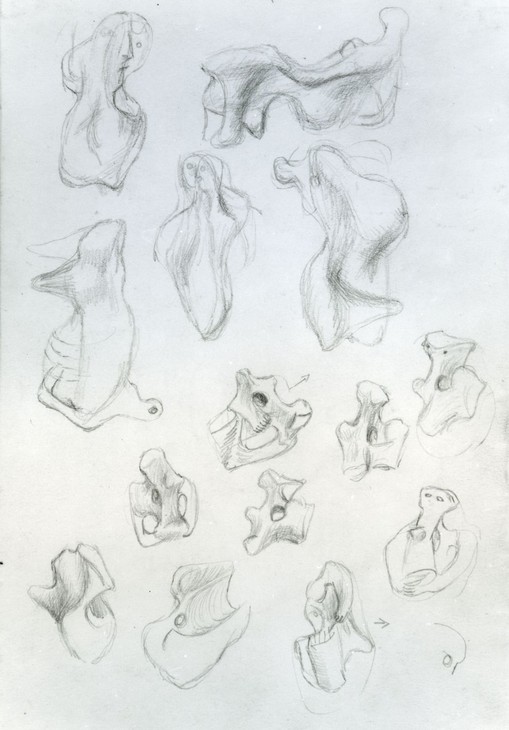

Direct carving and the principle of truth to materials led Moore and his contemporaries to think about the inherent qualities of their sculptural materials, and how those materials are shaped and manipulated in the natural environment. As well as meeting regularly to discuss artistic ideas with his Hampstead neighbours, who included Hepworth, Skeaping and Read, Moore and his friends took summer holidays together on the East Anglian coast, notably at Happisburgh in 1930 and 1931.5 Hepworth and Skeaping had accompanied Moore on the 1930 trip where the three of them became interested in the shapes and forms of the ironstone and flint pebbles found on the beach. In 1932 Moore explained:

During visits to the Norfolk coast I began collecting flint pebbles. These showed Nature’s treatment of stone and the principle of the opposition of bumps and hollows. Then I realised that a work loses in interest through having its component forms too similar in size, and began putting small forms against large forms, enlarging some and reducing others.6

This realisation may account for the arrangement of forms of different sizes in Figure. The sculpture includes a number of bumps, undulations and hollows – for example, the breasts, shoulders and chest area respectively – while the breasts themselves seem to be too large or too prominent in relation to the overall size of the sculpture.

Although the catalogue of Moore’s 1933 solo exhibition at the Leicester Galleries in London provides only limited information about the works that were on show, it is almost certain that Figure was included and displayed under the title Composition. According to Moore’s catalogue raisonné, published in 1957, Moore had only carved three sculptures in beech by 1933, and three beech sculptures were included in his exhibition at the Leicester Galleries, all titled Composition. An unnamed art critic reviewing the exhibition for the Times noted that Moore’s sculpture fell into two opposing categories, the figurative and the abstract, going on to observe that those sculptures in the latter category seem ‘to have grown out of the promptings of the material – as a man might work and polish a pebble which happened vaguely to suggest a human or animal figure’.7 Although the critic does not make reference explicitly to direct carving or truth to materials, it seems that Moore’s sculptures were nonetheless understood in these terms.

It is notable that the critic for the Times chose to use the term ‘abstract’ to describe some of Moore’s work. At the time, the word was applied to a wide range of different styles and artistic tendencies. For example, the influential art critics Herbert Read and R.H. Wilenski, both of whom had championed Moore’s work in their writing, had been using the word to describe artworks that evoked figures and objects that existed in the real world but which had been manipulated or transformed by the artist so as to arrive at a more or less simplified or schematised arrangement of forms. Echoing this sentiment, Moore remarked in 1932 that abstraction could denote taking ‘steps away from realistic representation’, to greater or lesser degrees.8 The term ‘abstract’, therefore, did not simply mean ‘non-representational’, which is why Figure could be described as being ‘abstract’ despite maintaining a resemblance to the human form.9

In 1934 Moore remarked that ‘all art is abstraction to some degree’, going on to note that ‘in sculpture material alone forces one away from pure [realistic] representation and towards abstraction’.10 In this statement Moore implies that because wood and stone are materially different from flesh and bone, a sculpture of a human figure in beech, for example, will be intrinsically abstract. It is up to the sculptor therefore to decide whether to hide or deny these abstract qualities by carving the figure naturalistically, or to assert this abstraction through the imaginative manipulation of the figure’s features.

Figure demonstrates how far Moore was prepared to move away, by 1931, from the naturalistic representation of human bodies while maintaining a commitment to it. Although Figure may only loosely resemble the features of a female figure, Moore identified human forms as the fulcrum of his work:

As with the flints I have studied the principles of organic growth in the bones and shells at the Natural History Museum and have found new form and rhythm to apply to sculpture. Of course one does not just copy the form of a bone, say, into stone, but applies the principles of construction, variety, transition of one form into another, to some other subject – with me nearly always the human forms, for that is what interests me – so giving, as the image and metaphor do in poetry, a new significance to each.11

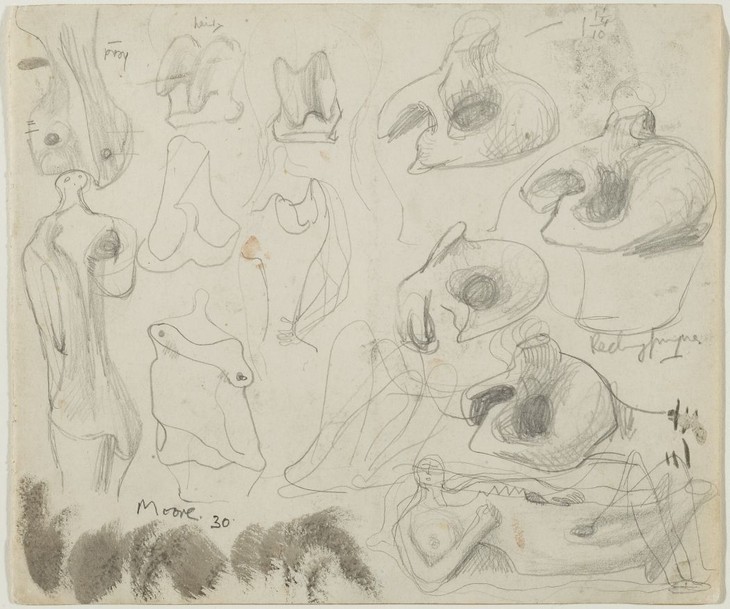

Henry Moore

Ideas for Sculpture 1930

Graphite and ink on paper

Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.3

Henry Moore

Ideas for Sculpture 1930

Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore

Bone Forms: Reclining Figures c.1930

Graphite on paper

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.4

Henry Moore

Bone Forms: Reclining Figures c.1930

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Photograph of Figure 1931 taken in c.1931–4, reproduced in Herbert Read, Henry Moore: Sculptor, An Appreciation, London 1934, pl.21

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.5

Photograph of Figure 1931 taken in c.1931–4, reproduced in Herbert Read, Henry Moore: Sculptor, An Appreciation, London 1934, pl.21

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photograph of Figure 1931 taken in 1959

Tate T00240

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.6

Photograph of Figure 1931 taken in 1959

Tate T00240

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

In November 1933 the literary critic Geoffrey Grigson wrote an article for the November edition of the journal Bookman encouraging readers to visit Moore’s exhibition at the Leicester Galleries in which Figure was displayed. In what was essentially a promotional preview of Moore’s exhibition, Grigson assured his readers that on visiting the show they would see ‘sculpture which is both intensely individual and, at its best, universal’.18 Grigson identified the organic forms of Moore’s sculptures as the products of a ‘passionate and undivided imagination’.19 What is notable about Grigson’s text is that he did not attempt to describe Moore’s sculpture but sought to convey the uplifting experience of viewing his works. Grigson suggested that Moore’s work needed to be understood emotionally, and only by seeing his art first-hand would the reader be able to experience its positive energy. What Grigson identified in Moore’s sculpture as ‘harmonious, surprising and exhilarating’,20 may be what Moore described as his work’s ‘vitality ... an intense life of its own, independent of the object it may represent’.21

Two years later Grigson discussed Moore’s sculptures such as Figure in his essay ‘A Comment on England’, published in the first edition of the magazine Axis. In his essay, Grigson characterised Moore as follows:

MOORE: Product of the multiform inventive artist, abstraction-surrealism nearly in control; of a constructor of images between the conscious and the unconscious and between what we perceive and what we project emotionally into the objects of our world; of the one English sculptor at large, imaginative power, of which is almost master; the biomorphist producing viable work, with all the technique he requires.22

In this statement Grigson condensed many of the underlying themes of his 1933 article. In both texts Moore is presented as an artist fuelled by a powerful imagination who makes familiar forms that give rise to emotional responses. However, what is different about Grigson’s 1935 text is his use of the term ‘biomorphist’ to describe Moore. In her catalogue essay for the 2010 Henry Moore exhibition at Tate Britain, art historian Jennifer Mundy explained that ‘for Grigson “biomorphic” denoted an organic quality that was an indelible residue of the way in which the [sculptural] form had been arrived at’.23 While ‘biomorphic’ may refer to organic shapes or memories of naturally occurring forms, the term ‘did not necessarily imply that the form looked like anything real’.24 Grigson’s identification of Moore as a ‘biomorphist’ – someone who uses biomorphic forms – enables an interpretation of Figure which recognises that although the sculpture may not look like a real human body it does nonetheless resemble a figure. In this interpretation, the sculpture may be regarded as an imaginative development of the bone shapes Moore had sketched in his Transformation Drawings. In 1934 Moore stated, ‘The observation of nature is part of an artist’s life, it enlarges his form-knowledge’.25 For Moore it was the notion of ‘form-knowledge’ that allowed sculptures such as Figure to comprise rounded, organic forms while retaining an attachment to human figuration. In 1936 the curator Alfred H. Barr identified biomorphic abstraction as the most significant new development in international abstract art, and named Moore as its paradigmatic representative in the catalogue of the exhibition Cubism and Abstract Art held at the Museum of Modern Art, New York.26 Mundy argued that by prioritising truth to materials and the organic qualities of his work, Moore and his critics were down-playing ‘otherwise salient aspects of the meaning and origins’ of his sculptures.27

Pablo Picasso

Untitled 1929, reproduced in Documents 3: Hommage à Picasso, 1930

© Succession Picasso/DACS

Fig.7

Pablo Picasso

Untitled 1929, reproduced in Documents 3: Hommage à Picasso, 1930

© Succession Picasso/DACS

Henry Moore

Half Figure No.1 1929

Cast concrete

425 x 255 x 185 mm

British Council Collection

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.8

Henry Moore

Half Figure No.1 1929

British Council Collection

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Sir Jacob Epstein 1880–1959

Torso in Metal from 'The Rock Drill' 1913–4

Bronze

object: 705 x 584 x 445 mm

Tate T00340

Purchased 1960

© The estate of Sir Jacob Epstein

Fig.9

Sir Jacob Epstein

Torso in Metal from 'The Rock Drill' 1913–4

Tate T00340

© The estate of Sir Jacob Epstein

Figure may be understood as the first in a series of works that contain sexualised subject matter. In 1973 critic John Russell located the eroticism of Figure not so much in the swelling breast-like forms but in the arched recess of the belly. He argued that ‘in giving a Romanesque arch to the diaphragm, Moore looked forward ... to the great Standing Reliefs of the 1950s whose most stirring feature is the enormous commotion, associated in life with a supreme degree of sexual fulfilment, in precisely this region of the body’.32 Russell identified the arched niche as the location of female genitalia and the site of sexual pleasure. Although he identified Figure as a precursor to Moore’s later works, he failed to note that Moore had used the arched niche in earlier sculptures such as Half-Figure No.1 1929 (fig.8). An alternative interpretation of the meaning of the arched spaces in both these works, however, suggests that the cavities signify empty wombs. In 2005 the art historian Anne Wagner related what she identified as Moore’s interest in the barren, empty womb to the recurring themes of mothers, babies, and pregnant women in British sculpture during the 1920s.33 An interesting point of reference in this context is Jacob Epstein’s The Rock Drill 1913–14 (fig.9), a work that Moore would certainly have known. Epstein’s armoured, mechanical figure turns its head over its left shoulder while its left arm arches forward as though protecting the foetus-like amoeba located in the arched recess in its belly.

It is also possible that the arched niche in Figure may have been influenced in part by the work of Leon Underwood, Moore’s former life-drawing tutor. In 1921 Underwood set up his own Brook Green School of Drawing at Girdlers Road, west London, following his resignation from the Royal College of Art (RCA). As a student Moore attended Underwood’s evening classes to supplement his studies at the RCA. Although Moore had stopped attending drawing classes in the mid-1920s he nonetheless remained a regular visitor to the Brook Green School, which was an important social venue where artists gathered and exchanged ideas. Following a series of fortnightly meetings that began in March 1931, Moore was one of a group of artists, poets and writers who contributed to a short-lived publication called the Island, launched in June that year.34 Containing poetry, art criticism and wood-cut illustrations, the contributors, or ‘Islanders’, shared a belief in ‘the power and significance of imagination, and in the realisation of the artistic self through an imaginative and spiritual existence’.35 Much of the content of the four issues of the Island had a romantic, spiritual tone. Underwood’s biographer Christopher Neve notes that ‘only Henry Moore concerned himself directly with the more practical aspects of social conditions in which contemporary art might flourish’.36

It is possible that Underwood’s artworks and texts reproduced in the Island provide Figure with an additional layer of meaning. The first issue included a wood-cut titled The Cathedral 1931 by Underwood, whose accompanying text identified the illustration as an architectural project, in which African, pre-Columbian and Sumerian sculptural forms were fused to create a multi-storey structure in the form of a female torso.37 Underwood had started a large-scale carving of The Cathedral in poplar wood in 1930 and described the project as the realisation of a ‘spiritual belief of the future’.38 Conceived as a ‘goddess with a gilded crown for a spire and dramatically ascending breasts for minarets’, visitors to Underwood’s proposed architectural structure would enter the female figure through an archway located in its abdomen.39 Identifying the niche in the torso of Figure as a ‘Romanesque arch’, John Russell inadvertently linked Moore’s work with The Cathedral. Cut at the waist, both sculptures feature a curved arched niche in their bellies, peaked breasts, an elongated neck and a pointed face. Although Moore’s Figure does not contain the overt symbolism of Underwood’s project, the presence of the niche in the sculpture’s torso, along with his participation in the Island suggests that Moore may have been aware of the formal characteristics of Underwood’s sculpture.

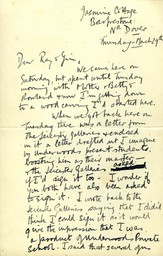

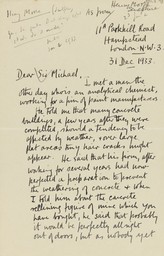

Sir Michael Sadler and Peter Gregory

In a letter dated 11 June 1959 to Martin Butlin, then Assistant Keeper at the Tate Gallery, Henry Moore stated that this sculpture was first exhibited in his second one-man exhibition at the Leicester Galleries in 1935, where it was bought by Sir Michael Sadler.40 However, Herbert Read’s 1934 publication identifies the work as already being in Sadler’s collection, and it is more likely that he acquired it from Moore’s first exhibition at the Leicester Galleries in 1933, where it was included under the title Composition.

Sir Michael Sadler (1861–1943) was Vice Chancellor of the University of Leeds when Moore began his studies at the Leeds School of Art in 1919. At Leeds Sadler was active in the University’s arts, drama and music societies, and he established a programme of public lectures on the arts by invited speakers including the art critic Roger Fry. Significantly, Sadler also made his private art collection available as much as possible, frequently lending and showing items to artists and students in the city. This is how Moore came to know Sadler during his time at Leeds School of Art. In 1973 Moore recalled, ‘Sadler had a Gauguin, a wonderful Gauguin, and a few other things. It was the Gauguin and a few ones like that which impressed me most. It opened up a world that was other than the Victorian, academic, art-school world’.41

Sadler first started collecting art in the early 1890s when he acquired works by John Ruskin, and his interest in modern art rapidly increased around the turn of the century. In January 1911 he attended Roger Fry’s Manet and the Post Impressionists exhibition at Grafton Galleries and later that year acquired works by Paul Cézanne and Gauguin. Other notable purchases included works by Eric Gill and Wyndham Lewis in 1919, and in the late 1920s and early 1930 he started collecting the work of Moore, Barbara Hepworth and Ben Nicholson. In 1934 Sadler sent funds to Alfred H. Barr, then director of the Museum of Modern Art, New York, so that the museum could purchase Moore’s wooden sculpture Two Forms 1934.42 Barr had seen the sculpture during a visit to London and ‘since he very much wanted the piece to be part of the museum’s permanent collection, Barr asked Moore whether there might be someone in England who would make it possible for the Museum of Modern Art to obtain the work’.43 Given that Sadler’s generosity facilitated the first acquisition of a Moore sculpture by an American gallery, he was undoubtedly one of Moore’s most important early patrons.

Detail of underside of base of Figure 1931

Tate T00240

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.10

Detail of underside of base of Figure 1931

Tate T00240

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

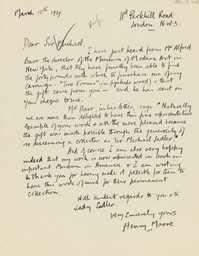

Known as Peter to his friends, Eric Craven Gregory (1888–1959) was an early supporter of Moore’s work and remained an important friend and patron throughout his life. He was a regular visitor to Moore’s home and accompanied Moore on his first trip to the United States in 1946. Gregory only bought works by living artists, believing that it was important to support art of the moment rather than create collections of the past, and his art collection numbered over 150 items and included paintings by Gillian Ayres, Sandra Blow, Alan Davie, Terry Frost, William Scott, and others.45 Figure remained in Gregory’s possession until his sudden death in February 1959, aged seventy-one. Among the numerous tributes published shortly after his death was an obituary written by Moore published in the Times:

I should like to add my personal tribute to the memory of my good friend Peter Gregory ... When first I knew him, I was an unknown sculptor. At that time there were very few, less than half a dozen collectors of modern sculpture in this country ... The debt that I owe him is enormous. It is thanks to Peter Gregory and a very few others of his sort that young sculptors in this country can nowadays anticipate that their work may be of interest to their compatriots ... He was always open to new ideas and directions. His heart remained young, and he was at all times ready to help those whose work he admired or who he felt needed the various forms of help that he could give. He gave his help quietly, unobtrusively, and for the right reasons.46

Following Gregory’s death, his executors, chaired by solicitor Leonard Wade, asked his friends Henry Moore, Herbert Read and poet T.S. Eliot to act as an art advisory committee providing advice on the distribution of his personal collection of paintings, sculptures and non-Western artefacts. Named beneficiaries, including the Tate Gallery, the Arts Council and the University of Leeds, were to have the opportunity to select works from the estate, and the remainder was to be sold at Sotheby’s auction house. Upon receiving the inventory of Gregory’s collection, the Tate trustees were given the first choice to select the six works promised to the gallery under the terms of Gregory’s will. Two sculptures by Moore, Figure 1931 and Half-Figure 1932 (Tate T00241), and one work each by Jean Arp (Tate T00242), Jean Dubuffet (Tate T00243), Louis Marcoussis (Tate T00244) and Vieira da Silva (Tate T00245) were selected. On the guidance of Moore, Read and Eliot, the executors also provided Tate with the opportunity to purchase a further twelve works prior to the auction sale. Although it was noted that Moore might have a conflict of interest, having his works in Gregory’s collection and being a former Tate trustee, he nonetheless was asked to draw up a list of appropriate purchases, including prices, for Tate in his capacity as art advisor to the Gregory estate. Following Gregory’s life-long example of supporting younger artists, Moore’s proposed acquisition list included works by the sculptors Reg Butler, Anthony Caro, Hubert Dalwood and Eduardo Paolozzi, and it was duly accepted by the Tate trustees.47

Photograph of Half-Figure 1932 and Figure 1931 on display at the Tate Gallery c.1959–60

Tate

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.11

Photograph of Half-Figure 1932 and Figure 1931 on display at the Tate Gallery c.1959–60

Tate

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

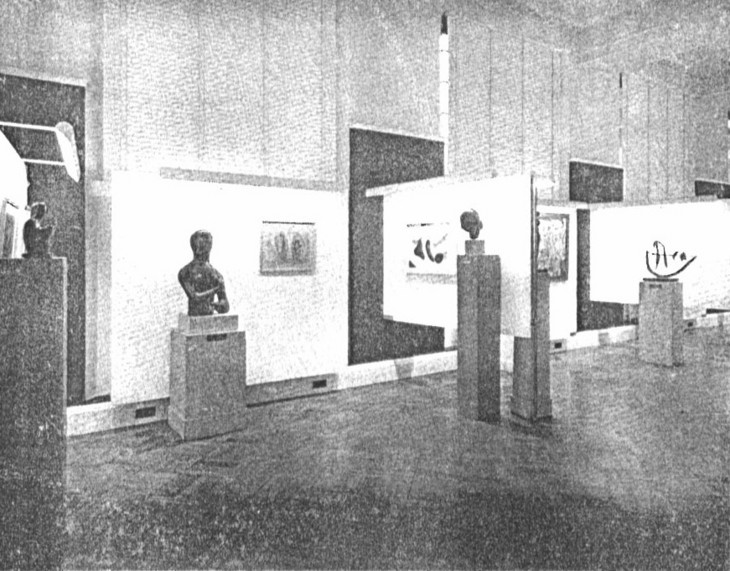

In 1959 the Tate Gallery’s ground floor exhibition spaces were redesigned.48 Improvements included the construction of screens which projected outwards into the galleries to create small bays, and the introduction of humidity and temperature control systems. The newly acquired small Figure was included in one of the re-hung galleries alongside Moore’s other sculpture from the Gregory Bequest, Half-Figure (fig.11).

Alice Correia

January 2013

Notes

The dual identification of the forms as breasts and knees is based on Moore’s use of the double peaked form to represents the knees of the female figure in Family Group 1949 (Tate N06004).

Henry Moore cited in Gemma Levine, Henry Moore: Wood Sculpture, London 1983, pp.20–3, reprinted in Alan Wilkinson (ed.), Henry Moore: Writings and Conversations, Aldershot 2002, p.225.

Henry Moore, ‘Statement for Unit One’, in Herbert Read (ed.), Unit One: The Modern Movement in English Architecture, Painting and Sculpture, London 1934, pp.29–30, reprinted in Wilkinson 2002, p.191 (Moore’s italics).

As curator Nicholas Thornton explains, these excursions provided a ‘friendly yet competitive environment, combined with the opportunity to share and develop ideas’. Nicholas Thornton, ‘Introduction’, in Henry Moore, Barbara Hepworth, Ben Nicholson in the 1930s: A Nest of Gentle Artists, exhibition catalogue, Norwich Castle Museum and Art Gallery, Norwich 2009, p.2.

Henry Moore cited in Arnold Haskell, ‘On Carving’, New English Weekly, 5 May 1932, p.65–6, reprinted in Wilkinson 2002, p.189.

Andrew Causey, ‘Herbert Read and Contemporary Art’, in David Goodway, Herbert Read Reassessed, London 1998, p.127.

The four studies on the upper right of this page have been connected to Moore’s sculpture in Cumberland alabaster, Composition 1931 (Henry Moore Foundation). See Ann Garrould (ed.), Henry Moore. Volume 2: Complete Drawings 1930–39, London 1998, p.36.

See Alan Wilkinson, Henry Moore Remembered: The Collection at the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto, Toronto 1987, p.71.

Geoffrey Grigson, ‘A Comment on England’, Axis, no.1, January 1935, p.10, quoted in Jennifer Mundy, ‘Comment on England’ in Chris Stephens (ed.), Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Tate Britain, London 2010, p.22.

See Christopher Green, ‘Henry Moore and Picasso’ in James Beechy and Chris Stephens (eds.), Picasso and Modern British Art, exhibition catalogue, Tate Britain, London 2012, p.139.

For a facsimile of Documents, vol.2, no.3, 1930, see http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k32951f.image , accessed 30 July 2012.

Henry Moore, ‘Interview with Elizabeth Blunt’, Kaleidoscope, radio programme, broadcast BBC Radio 4, 9 April 1973, transcript reprinted in Wilkinson 2002, p.167. For discussions of the debt Moore owed to Picasso see Herbert Read, Modern Sculpture, London 1964, pp.168–73, and Lichtenstern 2008, pp.47–52.

Anne Wagner, Mother Stone: The Vitality of Modern British Sculpture, New Haven and London 2005, p.24.

For a digital copy of Island, vol.1, no.1, June 1931, see http://www.fulltable.com/vts/i/island/a.htm , accessed 30 July 2012.

Henry Moore, letter to Martin Butlin, 11 June 1959, Tate Artist Catalogue File, Henry Moore, A23942.

Henry Moore cited in Donald Carroll, The Donald Carroll Interviews, London 1973, p.35, reprinted in Wilkinson 2002, p.44.

Fro Two Forms 1934 see http://www.moma.org/collection/browse_results.php?criteria=O%3AAD%3AE%3A4071&page_number=1&template_id=1&sort_order=1 , accessed 10 January 2013.

Oliver Brown, letter to Martin Butler, 29 April 1959, Tate Artist Catalogue File, Henry Moore, A23942.

Related essays

Related catalogue entries

Related material

How to cite

Alice Correia, ‘Figure 1931 by Henry Moore OM, CH’, catalogue entry, January 2013, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015, https://www