Life Forms: Henry Moore, Morphology and Biologism in the Interwar Years

Edward Juler

New images of microscopic life and theories of biological development impacted profoundly upon Moore’s practice, leading him to adopt in the 1930s a biomorphic sculptural idiom that echoed the forms of living nature.

In his polemical introduction to modern painting and sculpture, Art Now (1933), the British critic Herbert Read identified two ‘methods’, which he felt best described the approaches to art taken by contemporary artists. The first of these was an ‘empirical’ approach, which aimed to reproduce appearances. For Read, such dumb fidelity to surface appearances rendered the artist as little more than a slave to ‘the physiological mechanism of his sight’, and represented an aesthetic dead end.1 The second method – and in his opinion, the most productive – he labelled ‘scientific’. This approach required the artist to interrogate the structural nature of objects, in effect, playing the role of a scientist. The artist, Read wrote, ‘realises that the outward appearance of objects depends on their inner structure: he becomes a geologist, to study the formation of rocks; a botanist, to study the forms of vegetation; an anatomist, to study the play of muscles, and the framework of bones’.2

[The] artist makes himself so familiar with the ways of nature – particularly the ways of growth – that he can out of the depth and sureness of that knowledge create ideal forms which have all the vital rhythm and structure of natural forms ... Henry Moore has ... sought among the forms of nature for harder and slower types of growth, realizing that in these he would find the forms natural to his carving materials. He has gone beneath the flesh to the hard structure of bone5

Indeed, Moore, made no secret of his interest in natural history, peppering his statements with allusions to biological principles and organic form in the 1930s and later.6 Interviewed by Arnold Haskell in 1932, he spoke of the importance of morphology to his practice, explaining, in particular, his joy at discovering new biological precepts to apply to his art: ‘I have studied the principles of organic growth in the bones and shells at the Natural History Museum and have found new form and rhythm to apply to sculpture’.7 This essay will thus explore Moore’s biologistic leanings in relation to contemporary theories of morphology, biomorphism, neo-vitalism and organicism.

Shapes in transition: Moore, morphology and D’Arcy Wentworth Thompson

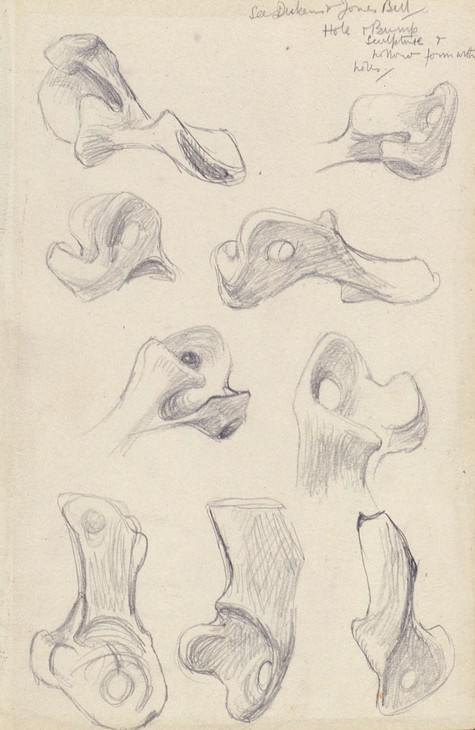

Henry Moore

Ideas for Sculpture: Transformation of Bones 1932

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.1

Henry Moore

Ideas for Sculpture: Transformation of Bones 1932

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

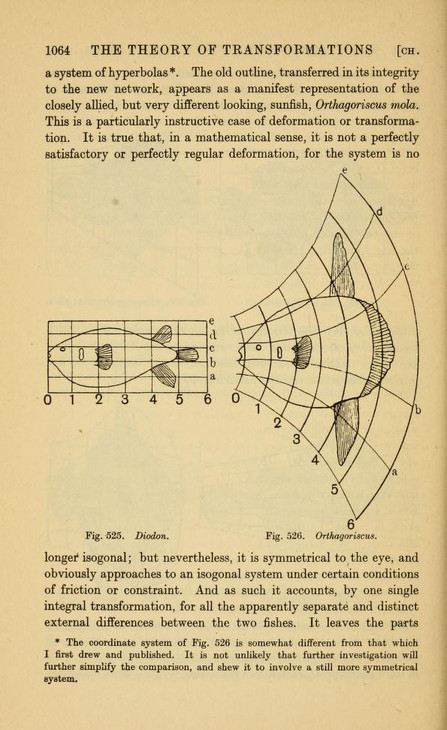

Here Moore’s familiarity with biology is evinced by the way in which the Transformation Drawings subtly echo the principles of organic form laid out in D’Arcy Wentworth Thompson’s morphological masterpiece, On Growth and Form (1917).9 A scholar of natural history, Thompson steadfastly believed that the laws of mathematics could be used to explain the principles of growth and form in living matter and spent many years developing a theory to elucidate how every biological object was effectively a ‘diagram of forces’, shaped in time and space by quantifiable physical energies.10 Thompson’s book was heralded by scientists as making a substantial contribution to the field of experimental morphology. On the one hand, his thesis presented evolution in novel terms, as a sudden and mercurial force, rather than (as was traditionally contended by Charles Darwin and his nineteenth-century disciples) something slow and steady. On the other, Thompson’s rigorous adherence to mathematical law proffered a timely riposte to the mysticism that had begun creeping into early twentieth-century biology.11 In the long run, Thompson’s work helped birth the science of biomathematics and, to this day, has influenced a wide array of disciplinary fields, including art, architecture, anthropology (his morphology possessed great resonance for the nascent structuralism of Claude Lévi-Strauss), geography and cybernetics, to name but a few.12

Thompson’s eloquent descriptions of living form sprouting, ballooning and metamorphosing into mathematically harmonious shapes particularly appealed to those artists who looked to nature for evidence of universal form values and for a re-vivifying alternative to contemporary abstraction’s mechanistic bias.13 For his part, Moore claimed to have first encountered On Growth and Form while a student at Leeds College of Art in the early 1920s,14 but, in truth, his interest formed part of a larger wave of modernist enthusiasm for the book which began during the 1930s and saw figures such as Read and the constructivist artist, Naum Gabo, introducing Thompson’s ideas to their close-knit circle of artistic and intellectual friends in London.15

Over and above its importance as a canonical work of morphology, On Growth and Form attracted non-specialists because of its apparent accessibility and Thompson’s tendency to launch into contemplative, lyrical discussions of the aesthetic and philosophical implications of ‘form’. Indeed, Thompson’s poetic style of exposition and fondness for literary and philosophical references encouraged non-specialist reviewers to applaud On Growth and Form’s artistic flair, proclaiming it to be as much a great work of literature as it was of science.16 In a review of the 1942 edition of On Growth and Form, Read enthused that Thompson was ‘of the same ‘blood and marrow’ as Plato and Pythagoras, and [had] something of the geniality of a Goethe or a Henri Fabre’ and, as such, his book should become ‘layman’s property and be given general currency’. Indeed, Read was in no doubt as to the volume’s importance to artistic practice, claiming that he felt ‘confidence in pointing out the significance which this science of form has for the theory of art’. ‘Never before has such a range of specific natural forms been shown to possess the harmony and proportion we usually ascribe only to works of art.’17

Fascinated by the psychology of beauty, Read’s interest in morphology had been piqued during the early 1930s when he first began researching ‘the motives that lead man to prefer one shape to another’.18 Describing the course of this research in his semi-autobiographical text, Annals of Innocence and Experience (1940), he explained that: ‘It was a short and obvious step to recognise at least an analogy and possibly some more direct relation, between [the] morphology of art and the morphology of nature. I began to seek for more exact correspondences, first by making myself familiar with the conclusions reached by modern physicists about the structure of matter, and then by exploring the quite extensive literature on the morphology of art’.19 These studies (which began as analyses of proportion in the BBC weekly, the Listener, in 1931) soon developed into a much bigger project in which Read sought to clarify how the Golden Section had played so ‘preponderant [a] part in the morphology of the natural world’ as well as art.20 Thus, On Growth and Form resonated particularly loudly for Read as Thompson, more than any other science writer, seemed to demonstrate ‘that certain fundamental physical laws determine even the apparently irregular forms assumed by organic growth’ and, in so doing, provided the grounds for analogizing between the morphologies of art and nature.21 Even though it is imaginable that his relationship with artists such as Moore and Gabo highlighted Thompson’s artistic significance for Read,22 his wider preoccupation with creating an ‘empirical’ theory of aesthetics stretched back a good deal further – to his previous incarnation as a literary critic and curator in the mid-1920s, when he acknowledged the role that physics and psychology had jointly performed in discrediting ‘transcendental reasoning’ while simultaneously shedding light on the ‘material origins of art’.23

Read’s engagement with morphology formed part of a wider current of enthusiasm for morphology which had begun, in 1914, with the publication of the British art critic, Theodore Cook’s The Curves of Life and which, arguably, reached its apogee with the publication of the Romanian mathematician and writer, Matila Ghyka’s 1931 aesthetic thesis, The Golden Number. Both of these publications were hugely important to Read’s developing morphological aesthetic; yet whereas Ghyka was cited as providing the ‘best up-to-date summary’ of the morphology of art it was On Growth and Form that Read recommended the reader consult to obtain ‘a more fundamental work, investigating the laws under which organic life evolves’.24

The Comparison of Related Forms: Diodon & Orthagoriscus in D'Arcy Wentworth Thompson, On Growth and Form (1942), New York 1992 (figs.525–6)

Fig.2

The Comparison of Related Forms: Diodon & Orthagoriscus in D'Arcy Wentworth Thompson, On Growth and Form (1942), New York 1992 (figs.525–6)

[It] is obvious ... that this [method] may also be employed for drawing hypothetical structures, on the assumption that they have varied from a known form in some definite way. And this process may be especially useful, and will be most obviously legitimate, when we apply it to the particular case of representing intermediate stages between two forms which are actually known to exist, in other words, of reconstructing the transitional stages through which the course of evolution must have successively travelled if it has brought about the change from some ancestral type to its presumed descendant.26

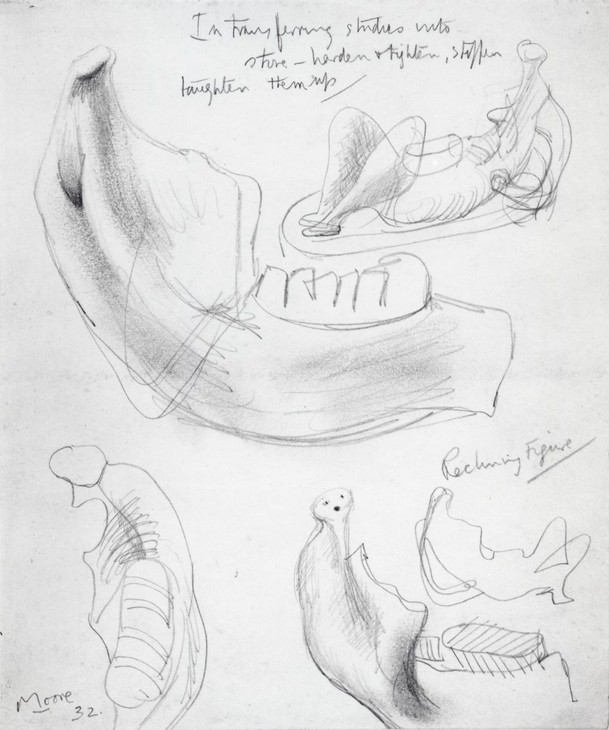

Henry Moore

Transformation Drawing: Studies of Bones 1932

The Moore Danowski Trust

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.3

Henry Moore

Transformation Drawing: Studies of Bones 1932

The Moore Danowski Trust

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Many of Moore’s morphological drawings include pencilled annotations scribbled across the page. These notes were used as a sort of creative shorthand for the sculptural process, enabling Moore to visually ad-lib upon the morphology of natural objects and imagine hypothetical forms, connected to the form depicted and yet part of a new and unique artistic configuration. Scrawled across the jawbone sketch, for example, is the legend: ‘In transferring studies into stone – harden & tighten, stiffen, taughten [sic] them up’.27 In a statement published in 1934 Moore summed-up the morphological properties of various natural objects in terms strikingly redolent of Thompson’s opus:28 ‘Bones’, he wrote, for example, ‘have marvellous structural strength and hard tenseness of form, subtle transition of one shape into the next and great variety in section. Trees (tree trunks) show principles of growth and strength of joints, with easy passing of one section into the next. They give the ideal for wood sculpture, upward twisting movement. Shells show Nature’s hard but hollow form and have a wonderful completeness of a single shape.’29 Here Moore’s comment on the formation of bones closely echoes Thompson’s elegant account of the morphological forces to which bones are subject during their growth cycles:

[We] have no difficulty in seeing that the anatomical arrangement of the trabeculae follows precisely the mechanical distribution of compressive and tensile stress ... The lines of stress are bundled close together along the sides of the shaft, and lost or concealed there in the substance of the solid wall of bones; but in and near the head of the bone, a peripheral shell of bone does not suffice to contain them, and they spread out and through the central mass in the actual concrete form of bony trabeculae.30

Given Read’s own deep knowledge of Thompson’s morphology, it is possible that this passage inspired his extraordinarily Thompsonian reading of Moore’s nature-centric practice. In his 1934 monograph on the artist he spoke of the natural forms that served as models for Moore’s work using Thompson’s language of tensile stress and strain: ‘Bones combine great structural strength with extreme lightness; the result is a natural tenseness of form. In their joints they exhibit the perfect transition of rigid structures from one variety of direction to another. They show the ideal torsions which a rigid structure undergoes in such transitional movements’.31 Conceptualised within a morphological framework, Moore’s practice thus symbolised the quintessence of Read’s ‘scientific’ method, in which the artist realised ‘that the outward appearance of objects depend[ed] on their inner structure: [becoming] an anatomist, to study the play of muscles, and the framework of bones’.32

‘The biomorphist producing viable work’: Moore and biomorphism

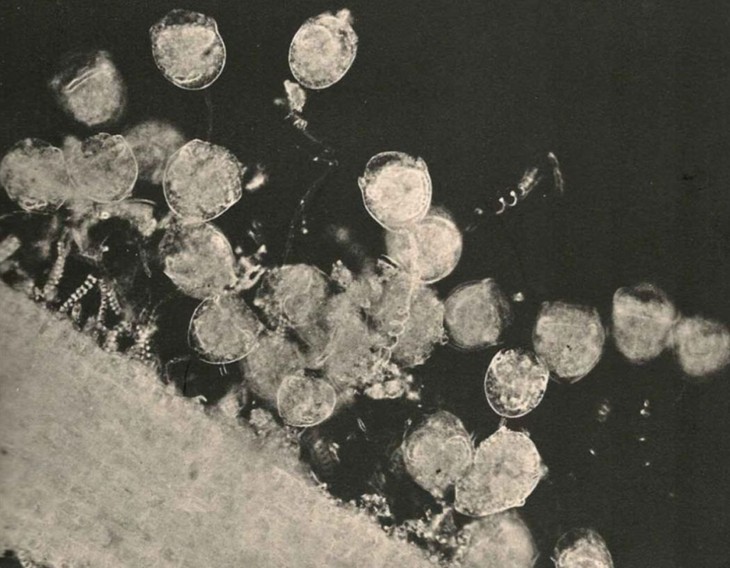

Biology’s centrality to Moore’s practice was discussed most fully by the English critic Geoffrey Grigson in his 1943 monograph titled simply Henry Moore. ‘Biology must be acknowledged’, he pleaded, as a wellspring of inspiration for the contemporary artist and nowhere was this more evident than in Moore’s turgescent, fluid shapes. These ‘may be related to a breast, or a pear, or a bone, or a hill ... But they might also relate to the curves of a human embryo, to an ovary, a sac, or to a single-celled primitive organism. Revealed by anatomy or seen with a microscope, such things are included now in our visual knowledge’.33

A poet by profession, Grigson founded the literary review New Verse in 1933 and, in the pages of the modernist art magazine Axis, formulated the term ‘biomorphism’ to describe the sort of organic, semi-abstracted forms favoured by Moore and some other contemporary artists.34 Drawing upon the nineteenth-century anthropology of Alfred Court Haddon and the biologistic criticism of the German art historian, Wilhelm Worringer, he coined the term to describe artworks that were neither representational nor wholly abstract but rather appeared to owe their origins, symbolically as much as, or more than, visually, to living things.35 In a couple of essays published in 1935, Grigson spelt out the aesthetic implications of the biomorphic idiom:

They are [artworks] in which an organic-geometric tension is very well obtained. Many of their forms are almost certainly ‘degraded’, as orthodox anthropologists would say, from organic forms which came nearer to nature. Some forms are further from any originals, and those have been described as ‘biomorphic’, which is no bad term for the paintings of Miro, Hélion, Erni and others, to distinguish them from the modern geometric abstractions and from rigid Surrealism.36

Within this critical framework Grigson left no doubt that it was Moore who most closely met his biomorphic ideals:

Product of the multiform inventive artist, abstraction-surrealism nearly in control; of a constructor of images between the conscious and the unconscious and between what we perceive and what we project emotionally into the objects of our world; of the one English sculptor of large, imaginative power, of which he is almost master; the biomorphist producing viable work, with all the technique he requires.37

While the appellation ‘biomorphic’ could refer to natural form in the widest possible sense – encompassing objects as diverse as, nuggets of bone and the shapes of animals – it nevertheless relied upon the findings of biology to articulate fully the range of meanings to which it was subject.38. Artworks that conveyed a sense of vitality – such as sculptures by Constantin Brancusi, Hans Arp and Moore – were discussed by Grigson in biological terms, as abstract ciphers of vital energies or microscopical forms: ‘It is Brancusi whose polished unicellular forms have been the basis for such different figures, more complex, more ‘impure’, as those of Mr Henry Moore’, he wrote in 1935.39 Yet while the fluid, protoplasmic forms of Arp and other biomorphic modernists evoked what Alfred Barr, director of the Museum of Modern Art in New York, would characterise as ‘the silhouette of an amoeba’,40 it was Moore’s swollen, pullulating shapes in wood and stone that – in Grigson’s eyes at least – most fully testified to biology’s influence on modernist art.41 ‘When I look at [Moore’s] carvings’, he wrote in 1943, ‘I sometimes have to reflect that so much of our visual experience of the anatomical details and microscopical forms of life comes to us, not direct, but through the biologist’.42

The smallest units of creation: photomicrography, bioromanticism and Moore

Photographic technology advanced enormously in the 1920s and 1930s.43 New methods of lens manufacturing better enabled the scientific visualisation of microscopic forms and tissue samples, while better lighting and staining techniques helped enhance the quality of the increasing number of micrographic images that found their way into the pages of the popular press.44 The photography critic G.H. Saxon Mills, writing in 1931, hinted at the artistic importance of these technological innovations by speaking of the ‘development, scope and possibilities’ of modern photography, arguing that in ‘scientific observation, by means of x-ray or astronomical research, and in its amazing development in the cinematic form, its form is as yet hardly explored’.45 Perceived as a sign of the contemporary age, photomicrography regularly appeared in the pages of photo-journals, and was readily identified as a symbol of the new photography.46 Scientific photography appeared ever more frequently in photographic publications designed for a general readership – such as Photography Yearbook – with special sections devoted to close-up photography alongside radiography, infrared imaging, telephotography and aerial photography.47

In tandem with photomicrography, microcinematography also developed rapidly as a field as early film pioneers such as Jean Painlevé and Jean Comandon thrilled European cinema audiences with speeded-up and slow motion films of aquatic life, single-celled organisms and sprouting plant-life.48 Despite the scientific community’s dismissive attitude towards the use of such films as 'entertainment', the new genre boomed in popularity, particularly delighting avant-garde viewers who saw, especially in Painlevé’s films, evidence of an aesthetic sensibility skilfully choreographing the wonders of nature.49 ‘The science films of Jean Painlevé’, wrote the French critic Elie Faure, ‘in showing the dancing and glittering life of a mosquito, bring to mind the enchantment of Shakespeare and allow one to glimpse the exhilaration of the mathematician lost in the silent music of infinitesimal calculations’.50 Nature-centric modernist artists – such as László Moholy-Nagy – championed the birth of these photographic technologies, claiming that a new age of mechanical objectivity would purify the aesthetic sensibility and destroy pictorialism’s bankrupt artistic pretensions. Indeed, for Moholy-Nagy, photography had dramatically revolutionised vision by optically re-framing humanity’s understanding of the visible world and allowing modern artists to engage anew with visual reality. His highly influential book of 1925, Painting Photography Film, gave visual form to the objective bent of the new photography. Using examples drawn from a wide range of photographic technologies (including illustrations of scientific photography, such as photomicrography and X-rays), Moholy-Nagy urgently demonstrated the new photography’s decisive break with pictoralist art and the dazzling range of vision that modern lens technology offered the artist. 51

In Britain the emergence of the documentary cinema movement significantly enhanced microcinematography’s presence in the public eye. By the end of 1929 almost a hundred natural history films had been produced by the company British Instructional under the series title of Secrets of Nature and shown to popular acclaim. An influential contributor to this series was Percy Smith, who had experimented successfully with making time-lapse films of plant life, which sped-up the process of growth by up to 96,000 times.52 While Secrets of Nature represented a diverse cinematic portfolio, ranging from feeding time at the zoo to meteorological documentaries, a significant number of its ‘shorts’ were microcinematographic films tackling topics like pond life, germination and insect life. Magic Myxies (1931), for example, revealed the magnified life cycle of a slime fungus, sped-up to take place within a ten minute time-span.

The proliferation of photomicrographic imagery led to frequent comparisons between modernist sculpture and microscopical form. In his photo-album of magnified natural structures, World beneath the Microscope (1935), W. Watson Baker accompanied the photograph of a sea-urchin shell, shot in extreme close-up, with the caption: ‘The modern sculptor must envy the massiveness of form, the grandeur of contour, of this small shell, whose dovetailing makes a strange and interesting pattern’.53 In turn, the modernist painter and critic John Piper felt that such photomicrographic enlargements revealed an underlying affinity between scientific photography and modern art: ‘It is amusing in fact to turn the pages and notice the artists suggested by the photographs: Klee (anchors and plates of Synapta), Ernst (a great many times), Miró (sponge spicules), Giacometti (chemical crystals), and so on’.54 Similarly, in an essay – published in Apollo in 1930 – the Scottish documentary film-maker, John Grierson, provocatively suggested that the ‘organic’ qualities of modernist sculpture stemmed from the influence of microcinematography on the optical unconscious:

It comes from a quickened consciousness of organic life which I am apt to think is the special stock-in-trade of a new generation. It may be that cinema has done something to open our eyes in this respect, with its power of revealing the constructions of plant life, animal life, and all life together in motion. It would still be more accurate to say that biology is getting into our blood. Certainly we become more conscious of the sculptural relations between these different worlds.55

On the question of artistic modernism’s relationship to scientific imaging technology Moore was just as forthright. In a text published in Unit One (1934), a book of artist statements edited by Herbert Read, he recognised that the evolution of scientific technologies had impacted upon his practice: ‘There is in Nature a limitless variety of shapes and rhythms (and the telescope and microscope have enlarged the field) from which the sculptor can enlarge his form-knowledge experience’.56

Henry Moore

Two Forms 1934

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.4

Henry Moore

Two Forms 1934

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Henry Moore OM, CH 1898–1986

Composition 1932

African wonderstone on oakwood base

object: 445 x 457 x 298 mm

Tate T00385

Presented by the Friends of the Tate Gallery 1960

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.5

Henry Moore OM, CH

Composition 1932

Tate T00385

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photomicrograph of Vorticella in W. Watson Baker, World Beneath the Microscope, London 1935 (plate 29)

Fig.6

Photomicrograph of Vorticella in W. Watson Baker, World Beneath the Microscope, London 1935 (plate 29)

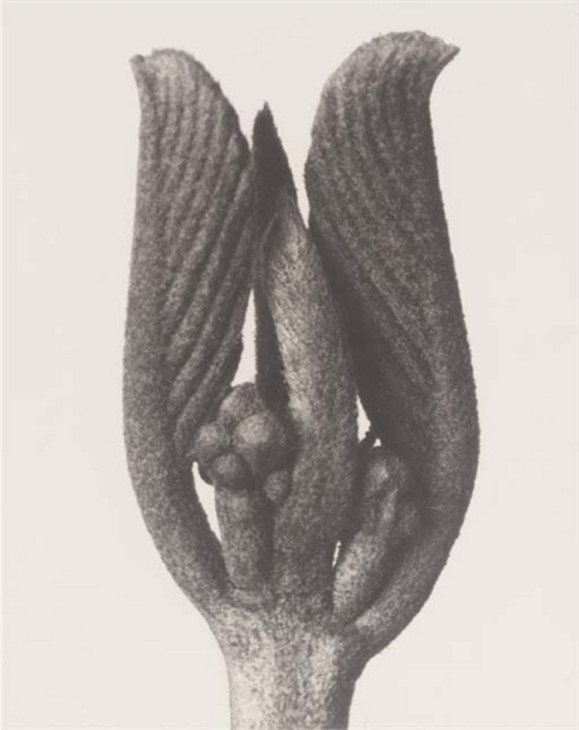

That photomicrography offered artistic modernists, like Moore, a form vocabulary that artfully blurred the boundaries between representation and abstraction was a refrain that echoed loudly within the pages of modernist magazines and reviews.58 Walter Benjamin – in a 1928 critique of Karl Blossfeldt’s photo-album of magnified plants structures, Art Forms in Nature – drew attention to the closeness of form between modern art and the images newly obtained by microscopy:59

Even the most impassive observer would be thrilled to see that the enlargement of parts of plants visible to the eye could be as extraordinary as plant cells glimpsed through a microscope. When we remember that Klee and, even more, Kandinsky worked for so long on the elaboration of forms which only the intervention of the microscope could – brusquely and violently reveal to us, we notice that these enlargements of plants also contain original stylistic forms.60

Karl Blossfeldt

Buck Thorn c.1915–25

Karl Blossfeldt Archiv

Fig.7

Karl Blossfeldt

Buck Thorn c.1915–25

Karl Blossfeldt Archiv

Obviously, in certain cases, natural forms have supplied a motif, but in many it would have been impossible to detect the significance of natural design without the aid of a mechanical process. This is where the camera’s ‘eye’ proves its incalculable power, but not as an archaeological, botanical or merely curious discoverer of ‘interesting’ comparisons between art and nature; its importance lies, surely, in the wealth of matter it places at the disposal of the modern sculptor or painter.65

Blossfeldt’s photographs also provided the basis for the critic Reginald Wilenski’s critique of modernist sculpture, The Meaning of Modern Sculpture (1932). The apparent orderliness and symmetry of Blossfeldt’s close-ups gave the lie to claims that the abstract prejudices of modernist sculpture were a rejection of ‘life’ and ‘nature’. On the contrary, noted Wilenski:

It is impossible to sustain the Romantic notion of a wild, free, ragged, ‘nature’ when we examine the enlarged photographs of plant forms in Professor Blossfeldt’s [books]. These photographs transform the apparently ragged constituents of a tangled hedgerow into a series of structures informed with a most definite shape, with most evident order and most evident logic. The study of these photographs makes it quite clear that ... the artist who gives us truth to form is the artist who symbolises the forms contained in the hedgerow by geometric forms.66

Henry Moore

Composition 1932

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.8

Henry Moore

Composition 1932

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

The impression that there was a powerful relationship between photographic technology and modernist art was hypothesised by the Hungarian art theorist Ernö Kállai during the late 1920s.69 Motivated by Benjamin’s critique of Blossfeldt and Moholy-Nagy’s 1929 Film und Foto exhibition, which aestheticised the new scientific photography, Kállai theorised that technology, especially microscopy and x-ray photography, had revealed the ‘deep structure’ of the world in ways that paralleled the aesthetic intuitions of artistic modernists.70 The type of art which appeared as a result of this biological insight – what perhaps might be termed biomorphic modernism – Kállai labelled ‘bioromanticism’ and saw, in quasi-mystical, neo-romantic terms, as a technological return to nature.71

Kállai’s biologistic speculations formed part of a larger wave of neo-romantic thought which emerged in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries as a philosophical response to the perceived shortcomings of materialism, positivism and mechanism and which included ‘a belief in the primacy of life and life processes, of biology as the paradigmatic science of the age, as well as an anti-anthropomorphic worldview’.72 This biologistic wellspring of neo-romantic sentiment held common cause against reductionist ideologies, preferring instead those philosophies – such as vitalism, holism and monism – which championed a pantheistic, holistic or biophilic attitude towards life.73

In Britain the impact of biologistic philosophies on thinking about the direction and values of contemporary art was evident not only in Grigson and Wilenski’s art criticism but also in the statements of Read and Moore, both of whom regularly espoused a biologistic viewpoint in their writings on art. Read, in particular, was inspired by the neo-vitalist theories of the French philosopher, Henri Bergson, whose vision of an incorporeal ‘vital’ impulse – the élan vital – which creatively shaped evolutionary development achieved widespread popular acclaim upon its publication in 1907.74 As late as 1955, Read maintained that ‘the inspiration I continue to receive from the only metaphysics that is based on biological science [is] the metaphysics of Henri Bergson’.75

In essence, neo-vitalism – from which Bergson’s philosophy derived – profoundly rejected the materialist idea that living organisms were simply complex machines and that ‘mind’ itself was little more than a by-product of biochemical processes. Instead, neo-vitalists recognised ‘life’ and ‘mind’ as dynamic, immaterial forces that actively intervened in the biological development of organic matter; yet, in so doing, flouted the accepted laws of chemistry and physics.76 Arguably, the greatest contemporary ally to the cause of neo-vitalism was the German biologist, Hans Driesch (1867–1941), whose experiments with sea-urchin embryos led him to think of organisms as dynamic self-adjusting bio-systems, the development of which was, to some extent, independent of physico-chemical forces.77 Translated by C.K. Ogden into English in 1914, Driesch’s work – like Bergson’s – was a catalyst for the emergence of the neo-vitalist movement in Britain and spurred writers and philosophers as diverse as D.H. Lawrence, George Bernard Shaw and C.E.M. Joad to introduce a vitalist, pantheistic viewpoint to their work.78 In the case of Read, the effect of neo-vitalism on his aesthetic is perhaps most evident in an early piece of writing on Moore – published in The Meaning of Art in 1931 – in which Moore’s ‘greatest success’ was defined as his ability to visualise form within the unshaped block of stone:

We cannot see all round a cubic mass; the sculptor therefore tends to walk round his mass of stone and endeavour to make it satisfactory from every point of view. He can thus go a long way towards success, but he cannot be so successful as the sculptor whose act of creation is, as it were, a four-dimensional process growing out of a conception which inheres in the mass itself.79

Here neo-vitalism is incorporated into an aesthetic that privileges the immaterial, creative agency of the artist. By likening the act of artistic creation to an élan vital which – like the kernel of a sprouting seed – implants within the block of stone or wood the germ of aesthetic vitality, Read equates Moore to a god-like creator ‘who [does] not replicate given objects, but adds new ones to the repertory of nature’ – an opinion that, as the art historian Rosalind Krauss has shown, was common within biocentric modernist circles in the 1930s.80 A neo-vitalist sensibility is similarly evident in Moore’s artistic philosophy. Just as an incorporeal life force animated inert matter in neo-vitalist dogma so Moore, in 1934, portrayed the expressivity of sculpture as a quality that was innate and not dependent upon mere similitude: ‘For me a work must first have a vitality of its own. I do not mean a reflection of the vitality of life, of movement, physical action, frisking, dancing figures and so on, but that a work can have in it a pent-up energy, an intense life of its own, independent of the object it may represent’.81 This neo-vitalist impression of ‘pent-up energy’ was deeply connected to the spatial disposition of the object, how it kinaesthetically enlivened the visual field. Asymmetry was central to this aesthetic for Moore as it greatly increased the number of viewpoints from which a sculpture could be apprehended, compelling the viewer to actively move around the object: ‘Sculpture fully in the round has no two points of view alike. The desire for form completely realized is connected with asymmetry. For a symmetrical mass being the same from both sides cannot have more than half the number of different points of view possessed by a non-symmetrical mass’.82

Importantly, asymmetry was recognised by modernist artists and critics as a morphological quality inherent to living organisms and powerfully illustrative of nature’s formative principles. Indeed Moore often spoke of how irregularity of form was a quintessential aspect of organic life: ‘Asymmetry is connected with the desire for the organic (which I have) rather than the geometric. Organic forms though they may be symmetrical in their main disposition, in their reaction to environment, growth and gravity, lose their perfect symmetry’.83 Moore derived this opinion from experimental morphology in which physical energies were seen to dynamically warp organic matter, like the amorphous shapes of wind-carved sandstone, into lop-sided or asymmetrical forms. D’Arcy Thompson wrote of how the distinct curvature of living form was the product of surface tensions and the contractility of cytoplasmic structures under the pressure of gravity or thermodynamic energies. This was particularly evident in the case of the amoeba – a primitive, single-celled organism – which he understood to be ‘the very negation of rest or of equilibrium [as the] creature [was] always moving, from one protean configuration to another; its surface tension [being] never constant, but continually [varying] from here to there’.84 As the surface tension of the amoeba’s watery, protoplasmic membrane was dynamically fluid, the tiny creature could never acquire symmetry; but, instead, passed rapidly from one distended, bulbous shape to another. Indeed, Thompson argued that, subject to extreme molecular forces, microscopic structures were always in a state of disequilibrium, producing forms that ‘are in continual flux and movement, each portion of the surface constantly changing its form, passing from one phase to another of an equilibrium which is never stable for more than a moment’.85

Jean Arp (Hans Arp)

Winged Being 1961

© DACS, 2015

Fig.9

Jean Arp (Hans Arp)

Winged Being 1961

© DACS, 2015

Throughout his life, Moore testified to the importance of science to his practice and enjoyed the friendship of internationally renowned scientists and engineers, such as the physicist Desmond Bernal and the zoologist Solly Zuckerman.92 Of these relationships, perhaps the most telling was his friendship with the evolutionary biologist Julian Huxley who, Moore claimed, would ‘often drive out here [with his wife Juliette] with little bits of bones or information. I mean they knew that I was very keen on bone structure, and Julian asked me to go and see on one occasion the skull of an elephant, which was the most wonderful sculptural object’.93 First broadcast in 1967, this statement – made on the occasion of Huxley’s eightieth birthday – demonstrates just how keenly biological theory and organic form continued to influence Moore’s aesthetic philosophy until late into his career. Enthused by the current of interest in biology and photomicrography that emerged within British and European modernist circles in the 1930s, Moore revealed deep bioromantic sympathies that enlivened his work from the 1930s onwards with vital rhythms and organic imagery.94

Notes

For a fuller exploration of the relationship between Moore and biology, see Edward Juler, Grown But Not Made: British Modernist Sculpture and the New Biology, Manchester 2015.

In using the term ‘nature-centric’ I am drawing upon Oliver Botar’s discussion of nature-centric neo-romanticism as ‘the biologistic wing of Lebensphilosophie, a philosophical variety which, based on the results of Natur philosophie and of 19th century science (especially biology), attempted to rethink philosophical categories such as “life” and “nature”, as well as epistemology, ethics and morality’. See Oliver Botar, Prolegomena to the Study of Biomorphic Modernism: Biocentrism, László Moholy-Nagy’s ‘New Vision and Erno Kállai’s Bioromantik, unpublished Ph.D. thesis, Toronto 1998, p.49.

Henry Moore in interview with Arnold L. Haskell in New English Weekly, 5 May 1932, pp.65–6, reprinted in Alan Wilkinson (ed.), Henry Moore: Writings and Conversations, Aldershot 2002, p.189.

Henry Moore, statement in Herbert Read (ed.), Unit One: The Modern Movement in English Architecture, Painting and Sculpture, London 1934, p.29.

For an excellent overview of D’Arcy Thompson’s work and legacy, see Matthew Jarron, ‘Editorial’ in Interdisciplinary Science Reviews, vol.38, no.1, March 2013, especially pp.4–5. See also M. Jarron and C. Caudwell, D’Arcy Thompson and his Zoology Museum in Dundee, Dundee 2010, p.53.

Robert Olby, ‘Structural and Dynamical Explanations in the World of Neglected Dimensions’, in T.J. Horder (ed.), A History of Embryology, Cambridge 1986, pp.288–9 and Jarron and Caudwell 2010, p.53.

See Charles Harrison, English Art and Modernism: 1900–1939, first published 1981, New Haven and London 1994, p.282. This nature-centric turn was verbalised by the painter Bernard Reynolds in a 1937 defence of Moore’s ‘vital’ carvings: ‘Most contemporary sculptors kill Nature, reduce it to non-sensitive geometric forms ... Henry Moore puts life into stone; his forms are ‘biomorphic’. In his opinion, if a piece of sculpture defies the vital laws of natural growth and construction, it is bad’ (Bernard Reynolds, untitled response to Henry Moore’s article, ‘The Sculptor Speaks’, Listener, no.453, 15 September 1937, p.575).

‘Moore was proud ... that he had discovered this book [On Growth and Form] in Leeds before he met Read’, D. Kosinski (ed.), Henry Moore: Sculpting the Twentieth Century, exhibition catalogue, Dallas Museum of Art, Dallas 2001, p.264.

See Martin Hammer and Christina Lodder, Constructing Modernity: The Art and Career of Naum Gabo, New Haven and London 2000, p.385. See Harrison 1994, p.282, and Jarron and Caudwell 2010, p.53.

Hammer and Lodder claim that it was Read who introduced Gabo to Thompson and, certainly, Read was prominent in promoting On Growth and Form’s aesthetic significance throughout the 1930s and 1940s. See Hammer and Lodder 2000, p.385.

See Christa Lichtenstern, ‘Henry Moore and Surrealism’, Burlington Magazine, vol.123, no.944, November 1981, pp.651–2.

Henry Moore, notes written across Ideas for Sculpture: Transformation of Bones 1932, reproduced in Ann Garrould (ed.), Henry Moore. Volume 2: Complete Drawings, 1930–39, London 1998, p.70.

See also Jennifer Mundy, Biomorphism, Ph.D. dissertation, Courtauld Institute of Art, University of London 1986, p.130.

See Geoffrey Grigson, ‘Comment on England’, Axis, no.1, January 1935, pp.8–10. It is important to note here that Grigson’s understanding of biomorphism drew upon archaeological and anthropological studies in which certain types of prehistoric art – most especially the decoratively painted pebbles that had been found in the Mas d’Azil cave complex, France – appeared to prefigure precisely the same type of ‘degraded’ semi-abstraction and ‘organic-geometric tension’ that he discerned in contemporary biomorphic abstraction. (See Jennifer Mundy, ‘Comment on England’, in Chris Stephens (ed.), Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Tate Britain, London 2012, pp.25–7). Grigson’s original definition of biomorphism was thus less connected to the biological implications of biomorphic form than was that of Alfred Barr, whose well known biologistic description of the biomorph as embodying the ‘silhouette of an amoeba’ has remained highly current up till the present day (see Mundy 1986, p.36).

Geoffrey Grigson, ‘Painting and Sculpture Today’, in Geoffrey Grigson (ed.), The Arts Today, London 1935, p.81.

Alfred Barr, Cubism and Abstract Art, exhibition catalogue, Museum of Modern Art, New York 1936, reprinted London 1964, p.19.

Drawing upon Grigson’s 1935 essays, Barr characterised biomorphic form as representing ‘the silhouette of an amoeba’ and ‘a soft, irregular, curving silhouette half-way between a circle and the object represented’ in Barr, Cubism and Abstract Art, pp.19, 186.

For more information on the popularisation of photomicrography in interwar Britain, see Edward Juler, ‘The Key to a Hidden World: Photomicrography and Close-up Nature Photography in Interwar Britain’, History of Photography, vol.36, no.1, February 2012, pp.87–98.

Loraine Daston and Peter Galison, Objectivity, New York 2010, pp.138–90, and Lynn Gamwell, Exploring the Invisible: Art, Science and the Spiritual, Princeton and Oxford 2002, p.210.

G.H. Saxon-Mills, ‘Modern Photography: Its Development, Scope and Possibilities’, Modern Photography, London 1931, p.4.

Brigitte Berg, ‘Contradictory Forces: Jean Painlevé, 1902–1989’, in A.M. Bellows and M. McDougall (eds.), Science is Fiction: The Films of Jean Painlevé, Cambridge and London 2000, pp.17–18.

Elie Faure, ‘De la Cinéplastique’, 1922, quoted in Berg, ‘Contradictory Forces: Jean Painlevé, 1902–1989’, p.19.

Dawn Ades, ‘Little Things: Close-up in Photo and Film 1839–1963’, in Dawn Ades and Simon Baker, Close-Up: Proximity and De-familiarization in Art, Film and Photography, Edinburgh 2008, pp.21–2.

For a short introduction to the history of Percy Smith and the Secrets of Nature team, see Timothy Boon, Films of Fact: A History of Science in Documentary Films and Television, London and New York 2008, pp.29–32.

While Blossfeldt’s photographs were extreme close-ups taken with a camera, critics typically interpreted them as images seen through a microscope. See Oliver Botar, Prolegomena to the Study of Biomorphic Modernism: Biocentrism, László Moholy-Nagy’s ‘New Vision’ and Erno Kállai’s Bioromantik, unpublished Ph.D. thesis, Toronto 1998, p.49.

Walter Benjamin, ‘New Things about Plants’ (1928) in David Mellor (ed.), Germany: The New Photography 1927–33, London 1978, p.21.

See Edward Juler, ‘The Key to a Hidden World: Photomicrography and Close-up Nature Photography in Interwar Britain’, History of Photography, vo.36, no.1, February 2012, pp.93–8, and Nigel Halliday, More than a Bookshop: Zwemmer’s and Art in the 20th Century, London 1991, pp.75–6.

In using the term ‘neo-romanticism’, I am here identifying a general desire – expressed by certain modernist artists such as Moore and Paul Nash – to re-enchant nature as well as reintegrate a technologically-alienated humanity with the living order of the natural world. See Botar, Prolegomena to the Study of Biomorphic Modernism, p.23 and Alan Powers, ‘The Reluctant Romantics: Axis Magazine 1935–6’, in David Peters-Corbett, Ysanne Holt & Fiona Russell (eds.), The Geographies of Englishness: Landscape and the National Past. 1880–1940, New Haven and London 2002, p.265.

While Moore may have been unaware of Kállai’s bioromantic hypotheses, Kállai had been on friendly terms with the sculptor Naum Gabo in the 1920s, when both had been resident in Berlin, and it seems likely that – after his move to London in 1936 – Gabo acted as a conduit through which Kállai’s theories were disseminated among British avant-garde circles. It should, of course, be noted that Kállai’s bioromanticism formed the thin end of a much wider discursive wedge in which critics and philosophers examined the relationship between visual culture and contemporary art, among whom can be counted Wilenski who employed the term ‘associationism’ to explain how cheap print technologies, cinema, photography, radio and new modes of intercontinental transportation (such as aviation) had created a situation in which it was possible to ‘capture contacts in all directions and compare things and find correspondences and associations across continents and ages’ (Reginald Wilenski, Modern French Painters, London 1940, p.272).

Botar 1998, p.65, and Oliver Botar, ‘Ernö Kállai and the Hidden Face of Nature’, Structurist, nos.23–4, 1983–4, p.77.

Oliver Botar and Isabel Wünsche, ‘Introduction: Biocentrism as a Constituent Element of Modernism’, in Oliver Botar and Isabel Wünsche (eds.), Biocentrism and Modernism, Farnham 2011, p.2.

See Sanford Schwartz, ‘Bergson and the Politics of Vitalism’, in F. Burwick and P. Douglass (eds.), The Crisis in Modernism: Bergson and the Vitalist Controversy, Cambridge 1992, pp.292–4.

Herbert Read, Icon and Idea: The Function of Art in the Development of Human Consciousness, London 1955, p.19.

For the history of vitalism, see Peter J. Bowler, Reconciling Science and Religion: The Debate in Early-Twentieth-Century Britain, Chicago and London 2001, especially pp.160–1.

See George Rousseau, ‘The Perpetual Crisis of Modernism and the Traditions of Enlightenment Vitalism’, in F. Burwick and P. Douglass 1992, p.57.

Ibid, pp.404–5. It should, of course, be noted that Thompson believed that symmetry was the norm in the case of higher, multicellular forms (see ibid., p.357).

See Mundy 1986, pp.129–30 and Guitemie Maldonado, Le Cercle et l’amibe: Le biomorphisme dans l’art des années 1930, Paris 2006, pp.187–202.

Henry Moore quoted in ‘Sir Julian Huxley: A Portrait of the Scientist on the Occasion of his Eightieth Birthday’, BBC, 22 June 1967, in Wilkinson 2002, p.88.

Edward Juler is an Honorary Fellow at the University of Edinburgh.

How to cite

Edward Juler, ‘Life Forms: Henry Moore, Morphology and Biologism in the Interwar Years’, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015, https://www