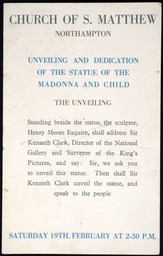

Biography

Alice Correia

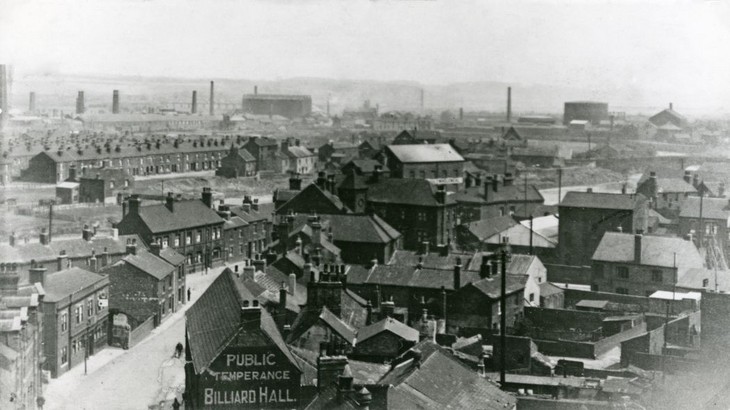

Henry Spencer Moore was born on 30 July 1898 at 30 Roundhill Road in Castleford, Yorkshire (fig.1). The son of Raymond Spencer Moore (1848–1922) and his wife Mary Moore (neé Baker; 1858–1944), Henry Moore was the seventh of eight children. His father was the grandson of an Irish migrant who, having started his working life on a farm, aged nine, moved to Castleford to work in the local coal mining industry. Moore’s father was self-educated and passed the examinations to become a qualified mine manager. His father was determined that his children would complete their education, and after attending infant and elementary schools in his hometown, Moore entered Castleford Secondary School, having passed the entrance exam on his third attempt.

Castlesford, Yorkshire c.1900

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.1

Castlesford, Yorkshire c.1900

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Moore excelled at art and sports at school and when he was eighteen he expressed a desire to sit the examinations for a scholarship to the local art college. Moore’s artistic ambitions had been encouraged by one of his teachers, Miss Alice Gostick, who was a member of the Art Teachers’ Guild. The Guild advocated a progressive curriculum and thanks to Miss Gostick, Moore was exposed to art magazines such as the Studio. This magazine often featured the work of modern European artists, and contemporary developments in art were freely discussed between the teacher and her students. Miss Gostick also ran evening pottery classes for both students and parents. Although Moore’s father was ambitious for his children, he disapproved of Moore’s desire to attend art school and insisted that Moore should train as a teacher, like his older brother and sister, in order to secure himself a living; if after qualifying as a teacher his son still wanted to become an artist he was free to do so. In 1915 Moore graduated from Castleford Secondary School with distinction in art and in July of that year became a student teacher at Temple Street Elementary School where he had studied as a child.

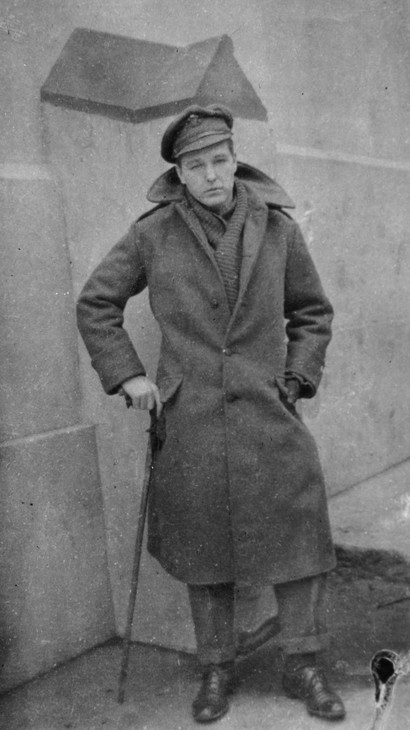

Moore shortly after he joined the army as a private in 1917, aged eighteen

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.2

Moore shortly after he joined the army as a private in 1917, aged eighteen

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

After a short period of training Moore was dispatched to the front in France in the summer of 1917. In November and December 1917 Moore’s battalion took part in the Battle of Cambrai, in which British and allied troops penetrated the German Hindenburg line in northern France by deploying large numbers of tanks. The German counterattack used aeroplanes to bomb and gas British troops. A witness later recalled:

The gas in Bourlon Wood hung in the trees and bushes so thickly that all ranks were compelled to wear their respirators continuously if they were to escape the effects of the gas. But men cannot dig for long without removing them, and it was necessary to dig trenches to get away from the persistent shell fire. Throughout November 30th there was, therefore, a steady stream of gassed and wounded men coming thought the regimental aid posts. Their clothes were full of gas.1

Henry Moore on recuperation leave, spring 1918

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.3

Henry Moore on recuperation leave, spring 1918

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Moore was later to recall of his short army career that ‘it was in those years that I broke finally away from parental domination which had been very strong’.3 Although he resumed his teaching post at Temple Street Elementary School in March 1919, with the assistance of Miss Gostick, he applied for, and received, an ex-serviceman’s grant to attend Leeds School of Art.

Miss Gostick's pottery class, with Miss Gostick seated on the far left looking at a bowl and Moore seated at her feet painting a jug, December 1919

Tate Archive

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved.

Fig.4

Miss Gostick's pottery class, with Miss Gostick seated on the far left looking at a bowl and Moore seated at her feet painting a jug, December 1919

Tate Archive

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved.

Harry and I met in the lavatory. We both had brand new serge suits on: it was a sort of mark of respectibility. I thought his eyes had a twinkle, and he was cheerful and had a nice taste for a smutty story. There was a gaiety about us, but it didn’t interfere with our will to get a lot done quickly. We were aiming at Michelangelo and Titian, nothing less. We were trying to make up for the lost time in the army. We were young, and we were thankful to God Almighty that we had survived.5

Although Moore found the teaching at Leeds uninspired, he and his fellow students were exposed to contemporary European art thanks to the activities of Michael Sadler, the Vice Chancellor of the University of Leeds from 1911 to 1922. Having worked at the Department of Education in London, Sadler took up the post of Vice Chancellor in Leeds in 1911, and brought with him a belief in the necessity of a broad education and the centrality of the arts in everyday life. At Leeds Sadler was active in the University’s arts, drama and music societies, and he established a programme of public lectures on the arts. In addition to giving lectures on artists such as Cézanne, Gauguin and van Gogh, he invited a range of guest speakers including the painter and critic Roger Fry.

Sadler was passionate about modern art and his eclectic art collection contained works by Cézanne, Gauguin, and the German Expressionists. In 1912 he had visited Wassily Kandinsky and had bought examples of his work.6 As Hilary Daiper, former Keeper of the University of Leeds art collection noted, Sadler’s ‘activities placed him at the centre of creative experiment in Leeds’.7 Significantly, Sadler made his private art collection available as much as possible, frequently lending and showing items to artists and students in the city. He also invited talented students, including Moore, to view his collection in his home and it was here that Moore saw Sadler’s painting by Gauguin. In 1973 he recalled, ‘Sadler had a Gauguin, a wonderful Gauguin, and a few other things. It was the Gauguin and a few ones like that which impressed me most. It opened up a world that was other than the Victorian, academic, art-school world’.8 Sadler later became one of Moore’s earliest patrons, buying works in the late 1920s.

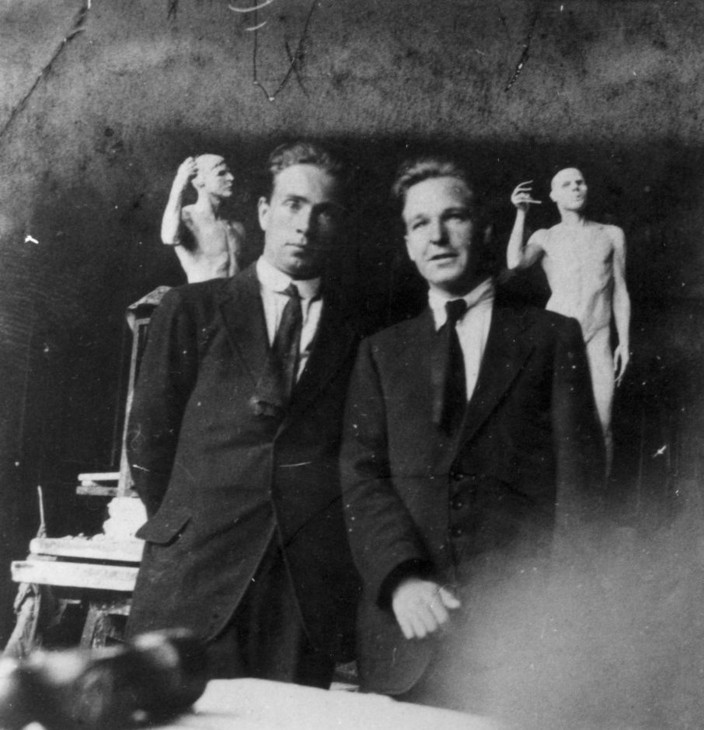

Raymond Coxon and Henry Moore standing in front of clay figures they had made, Leeds School of Art, summer 1921

Tate Archive

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Fig.5

Raymond Coxon and Henry Moore standing in front of clay figures they had made, Leeds School of Art, summer 1921

Tate Archive

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Moore moved to London in the autumn of 1921 and his letters to his friends in Leeds and Miss Gostick reveal that he embraced the new opportunities to see and learn about art. He quickly established a routine of weekly visits to the British Museum and the Tate Gallery, and he regularly visited other museums including the Victoria and Albert, Science Museum and the Wallace Collection. On 29 October 1921 Moore wrote to his Leeds friend and fellow sculptor Jocelyn Horner, ‘when I’m not at College I’m hockeying or Tate-ing or Museuming’.12 Moore later recalled:

I was in a dream of excitement. When I rode on the open top bus I felt I was travelling in Heaven almost, and that the bus was floating in the air. And it was Heaven all over again in the evening, in the little room that I had in Sydney Street. It was a dreadful room, the most horrible little room that you can imagine, and the landlady gave me the most awful finnan haddock for breakfast every morning, but at night I had my books, and the coffee stall on the Embankment if I wanted to go out to eat, and I knew that not far away I had the National Gallery and the British Museum and the Victoria and Albert with the reference library where I could get at any book I wanted. I could learn about all the sculptures that had ever been made in the world. With the £90 a year that I had in scholarships I was one of the real rich students at the College and I had no worries or problems at all except purely and simply my own development as a sculptor.13

Moore’s visits to London’s museums fuelled his appreciation for non-Western art. However, as Berthoud explained, ‘his taste for the primitive was in direct conflict with what he was being taught at the Royal College’.14 When Moore began the course, academic teaching of sculpture focused almost entirely on figuration, and was concerned above all with the styles and techniques of ancient Greek and Roman statuary and Italian Renaissance art. Under the leadership of Professor Francis Derwent Wood (1871–1926), a member of the Royal Academy, students in the RCA sculpture department were taught how to copy classical sculptures by accurately modelling replicas in clay or plaster before using a pointing machine to create a stone copy.15 Students were required to copy historical sculptures, working from plaster casts from the college’s collection, or from originals housed in London’s museums. In this way they were trained not only in traditional sculpting techniques but also in the styles and subjects of great art of the past.16 In order to balance his own interests with the demands of his course Moore led something of a double life:

I had a double goal, or double occupation: drawing and modelling from life in term-time and daytime. And the rest of the time trying to develop in pure sculptural terms – which for me, at that time, was a very different thing from the Renaissance tradition ... When I was a student direct carving, as an occupation and as a sculptor’s natural way of producing things, was simply unheard of in academic circles ... I liked the different mental approach involved – the fact that you begin with the block and have to find the sculpture that’s inside it.17

Raymond Coxon had also been awarded a scholarship to attend the Royal College and after the first term he and Moore lived together in a number of different lodgings in west London. In early 1922 Moore and Coxon sought permission from the Principal of the RCA, William Rothenstein, to go to Paris during Whitsun week in June 1922,18 with the express intention of studying Cézanne’s work.19 Rothenstein, who had only been appointed to the post of Principal in autumn 1920, had an appreciation for new developments in art, agreed to the trip. While in Paris Moore and Coxon visited Auguste Pellerin’s collection of paintings, which included Cézanne’s The Large Bathers 1900–6 (Philadelphia Museum of Art). Moore later recalled: ‘Cézanne’s figures had a monumentality about them I liked. In his Bathers, the figures were very sculptural in the sense of being big blocks and not a lot of surface detail about them. They are indeed monumental’.20

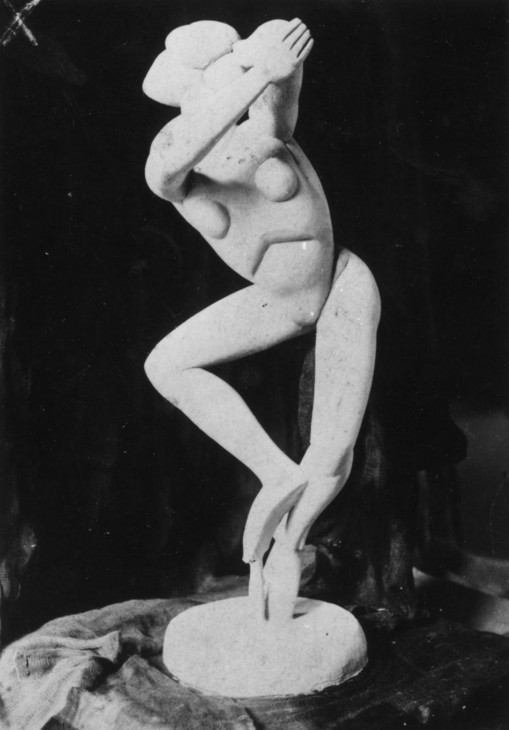

Although no records confirm what else they may have seen in Paris, it is possible that the now-lost plaster dancing figure created by Moore while living with Coxon in Acfold Road, was executed after seeing contemporary works by artists such as Alexander Archipenko, Ossip Zadkine or Henri Laurens (fig.6). That Moore made this work in his home, rather than his studio space at college, demonstrates how he kept his experiments with modern styles separate from his college work.

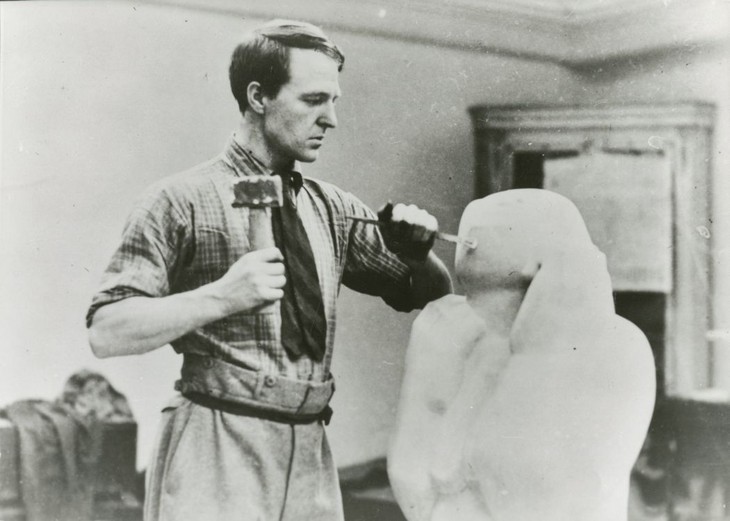

Moore at work in his Hammersmith studio, c.1925–6

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.7

Moore at work in his Hammersmith studio, c.1925–6

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

The first two or three years of teaching your own subject is as much a way of learning for the teachers as for the students themselves. I remember I used to be very surprised quite often at the things I discovered while teaching, the actual sentences, the words ... and after a few years of teaching then I think it isn’t a very good thing, because there comes a stage when you have to repeat things that you think are fundamental in the training of sculpture. They become deadening things.23

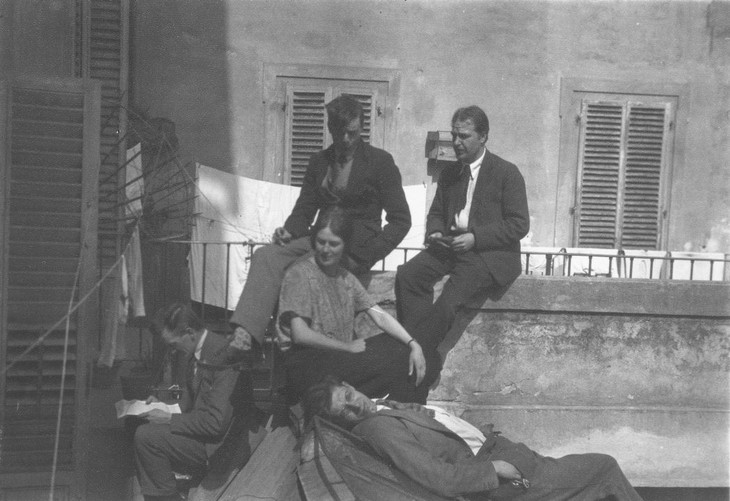

Henry Moore with fellow students, including the painter Eric Ravillious, in Rome, 1925

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.8

Henry Moore with fellow students, including the painter Eric Ravillious, in Rome, 1925

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

For about six months after my return I was never more miserable in my life. Six months exposure to the master works of European art which I saw on my trip had stirred up a violent conflict with my previous ideals. I couldn’t seem to shake off the new impressions, or make use of them without denying all that I had devoutly believed in before. I found myself helpless and unable to work. Then gradually I began to find my way out of my quandary in the direction of my earlier interests. I came back to ancient Mexican art in the British Museum.25

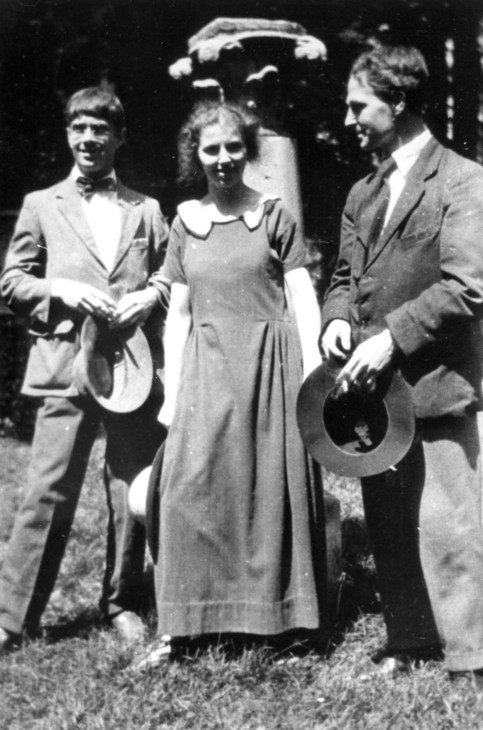

Henry Moore with Raymond Coxon and Edna (Gin) Ginesi in the garden of Musée Cluny, Paris, 1926 or 1927

Tate Archive

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.9

Henry Moore with Raymond Coxon and Edna (Gin) Ginesi in the garden of Musée Cluny, Paris, 1926 or 1927

Tate Archive

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

This is an account of today + yesterday. Up about 9 – begin carving about 10 carve for an hour then stretch my legs by getting a pear or two off the pear tree then to it again till 12.30 – lunch + read the Daily News till 2 – carve again till 4 then tea after which a game of croquet! Followed by a walk – another meal and then read and talk till bedtime. My aim now is to increase the hours of carving but cutting down the croquet and the paper reading ... I’m afraid this is going to be my worst Summer Holiday output for about 5 years ... The piece of stone I’m starting on is blamed hard – Its almost breaking my heart. For the last five months working in soft stone has made me like it myself – A bit of hard stuff causes me [to] take frequent rests + to sweat vulgarly.26

1928 was a significant year for Henry Moore. In January his first solo exhibition opened at the Warren Gallery, London, with forty-two sculptures and fifty-one drawings. Although Moore had exhibited in a number of group exhibitions during the 1920s, his show at the Warren Gallery was the first in which he exhibited a large group of sculptures and drawings together. The Warren Gallery was run by Dorothy Warren who, in 1961, Moore remembered as ‘a remarkable person with tremendous energy and real verve, real flair’.27 Moore’s exhibition was one in a series that presented the work of artists whose fathers had been miners. The series started with a sell-out exhibition of paintings by Evan Walters (1893–1951) and concluded with a controversial display of paintings by D.H. Lawrence, which were seized by the police.28 Moore went on to recall that although several sculptures were sold during the exhibition, it was his drawings that proved to be most successful commercially.29

Moore’s 1928 solo exhibition put him in the public eye and was an important factor in the establishment of his artistic career. Although some reviews were negative, most concurred that Moore was a young artist with potential. The reviewer for the Times concluded that although Moore’s abilities as a carver were not in question, ‘his actual sense of form is not yet highly developed’.30 One of the most positive reviews came from the Yorkshire Evening Post, although the reviewer approached the exhibition from a very particular perspective: under the title ‘Yorkshire Miner’s Artist-Son: Unconventional Work by Castleford Man’, the unnamed London correspondent prioritised Moore’s roots in Yorkshire as the key to understanding his exhibition. Making reference to Warren’s idea of exhibiting work by the children of miners, the author claimed that ‘Mr. Moore’s sculptures and drawings are full of primitive vitality which derives in some degree from the sturdy mining stock from which the artist springs’.31 Building on this notion that Moore’s art somehow originated from his father’s occupation, the reviewer went on to suggest that his sculptures ‘radiate vitality and masculine strength’.32

Photograph of Henry Moore carving the West Wind 1928 on the façade of the London Underground headquarters

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.10

Photograph of Henry Moore carving the West Wind 1928 on the façade of the London Underground headquarters

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Irina and Henry Moore on their wedding day, July 1929

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.11

Irina and Henry Moore on their wedding day, July 1929

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

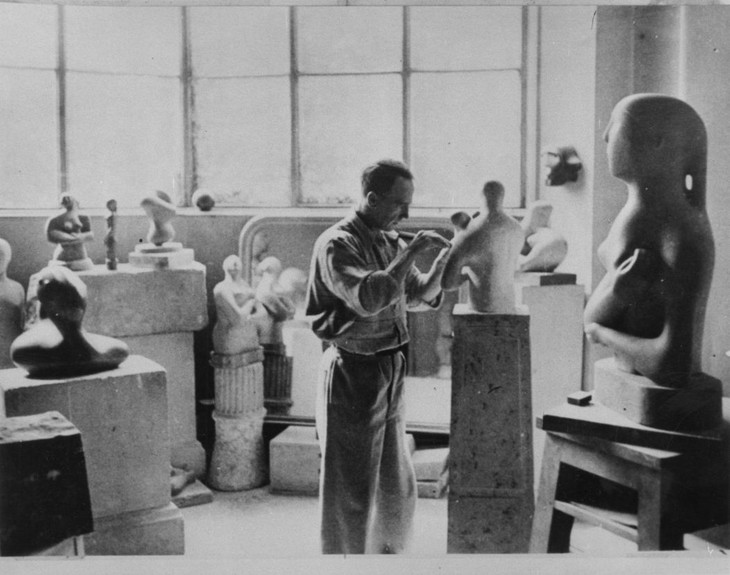

Henry Moore in his studio in 1932 with Half-Figure on original oval base

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.12

Henry Moore in his studio in 1932 with Half-Figure on original oval base

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Moore’s second solo show was held in April 1931 at the Leicester Galleries. Most reviews of this exhibition were mixed, with some, such as the unnamed critic for the Sheffield Independent, noting that Moore’s sculpture had ‘already aroused some criticism as ultra modern’.36 The reviewer for the Star saw Moore’s affinities with ancient Mexican sculpture with bemusement, while the critic for the Morning Post argued that ‘the cult of ugliness triumphs at the hands of Mr. Moore’ and lamented the waning influence of the classical Greek Elgin Marbles in the British Museum.37 However, more important for Moore and his burgeoning career than these reviews was the fact that Epstein wrote a prefatory note for the exhibition catalogue: he concluded that ‘for the future of sculpture in England Henry Moore is vitally important’.38

Notwithstanding this, Moore’s exhibition was heavily criticised by the older and more traditional members of staff at the Royal College, who questioned whether Moore should be allowed to teach sculpture there. Moore wrote to Rothenstein resigning from his post at the Royal College of Art in January 1931, and his resignation was reluctantly accepted. However, there is some uncertainty over whether Moore’s resignation was with immediate effect, or if he worked until the end of his contract, at the end of the summer term.39 Moore was keen to get on with his career as a sculptor, and in mid-1931 he and Irina purchased Jasmine Cottage in Barfreston in Kent for £80. Moore also retained his Hampstead studio and travelled regularly between his two homes during the holidays in order to fulfil his teaching duties. These working and travel arrangements continued when, in September 1931, Moore was appointed the first head of the newly formed Sculpture Department at Chelsea School of Art.

Photograph of Henry Moore standing in front of a cliff, Happisburgh, 1931 (taken by Ben Nicholson?)

Tate Archive

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.13

Photograph of Henry Moore standing in front of a cliff, Happisburgh, 1931 (taken by Ben Nicholson?)

Tate Archive

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

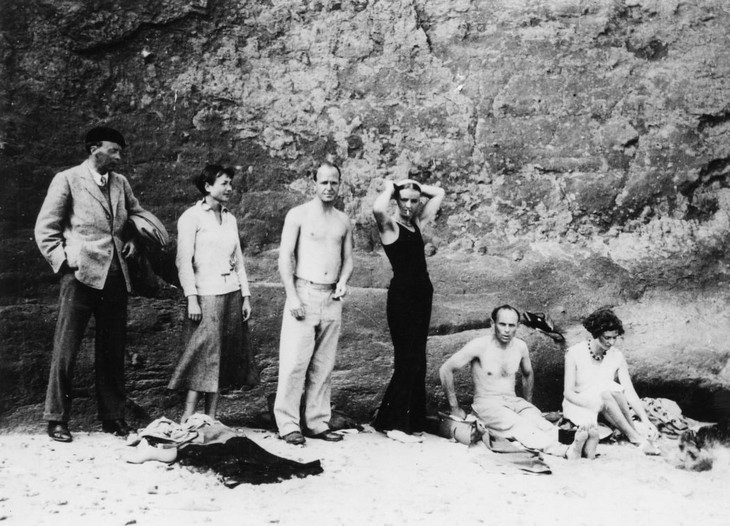

Henry, Barbara and I used to pick up large iron-stone pebbles from the beach which were ideal for carving and polished up like bronze. I rode and fished on the broads. Henry accompanied me on one of my fishing trips but he couldn’t leave sculpture alone for long and took with him a piece of iron-stone and a rasp. Sitting at one end of the boat he filed away continuously, occasionally hauling in his line to see if he had got anything on the end.41

Ivon Hitchens, Irina Moore, Henry Moore, Barbara Hepworth, Ben Nicholson and Mary Jenkins on holiday at Happisburgh in Norfolk, 1931

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Douglas Jenkins, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.14

Ivon Hitchens, Irina Moore, Henry Moore, Barbara Hepworth, Ben Nicholson and Mary Jenkins on holiday at Happisburgh in Norfolk, 1931

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Douglas Jenkins, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Unit One was the brainchild of the painter Paul Nash, and the aim of the group was to exhibit and champion the work of a diverse group of artists, architects and designers for the furtherance of a school of art that could be ‘both British, and modern’.43 As well as Nash, Moore, Hepworth and Nicholson, members included the architect Wells Coates, and painters Edward Wadsworth and Edward Burra. The group’s first exhibition took place at the Mayor Gallery, London, in April 1934, and it subsequently toured to six cities including Swansea, Manchester and Belfast. When the exhibition was shown in Liverpool it was visited by 30,000 visitors in four weeks.44 Shortly after the completion of this exhibition however, Unit One imploded, with its members all championing their particular artistic ethos to the detriment of others. Although Moore, Nash, Coates and Herbert Read spent a considerable amount of time between December 1934 and February 1935 attempting to resolve the group’s problems it was decided that further attempts of re-organising the group were futile.

During this time, and unbeknown to Moore, in May 1933 the painter and left-wing activist Clive Branson had offered his large collection of artworks works to the Tate. This included two sculptures by Henry Moore, four oil paintings by William Coldstream and a watercolour by Frances Hodgkins. The offer was rejected, however, by Tate’s director J.B. Manson and the Board of Trustees. In 1939 Manson would reiterate his opposition to Moore, telling Tate Trustee Robert Sainsbury, ‘Over my dead body will Henry Moore ever enter the Tate’.45

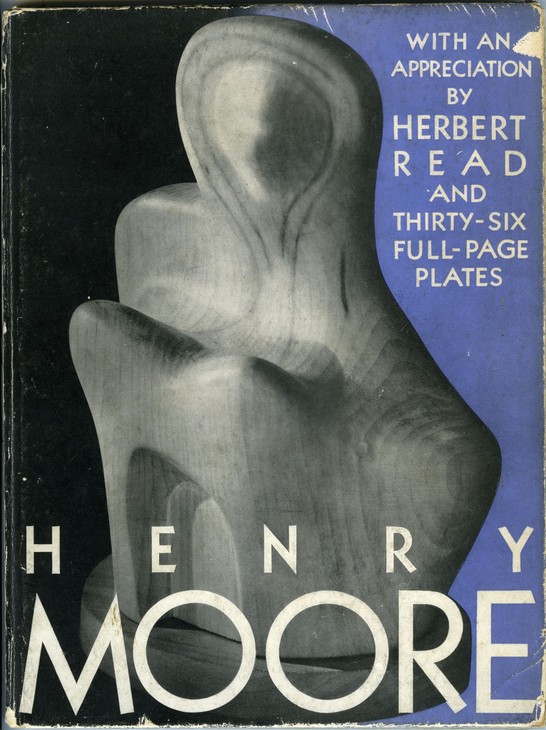

Front cover of the first monograph on Henry Moore, with an appreciation by Herbert Read, 1934

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.15

Front cover of the first monograph on Henry Moore, with an appreciation by Herbert Read, 1934

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Henry Moore

Two Forms 1934

Pyinkado wood

279 x 546 x 308 mm

Museum of Modern Art, New York

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Fig.16

Henry Moore

Two Forms 1934

Museum of Modern Art, New York

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Burcroft 1939

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.17

Burcroft 1939

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

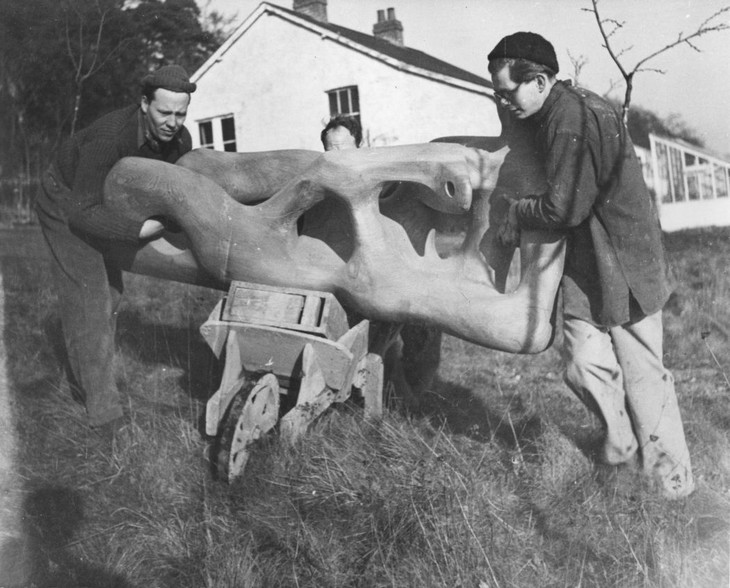

An unidentified helper with Moore and Bernard Meadows moving Reclining Figure 1939 at Burcroft in 1939

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.18

An unidentified helper with Moore and Bernard Meadows moving Reclining Figure 1939 at Burcroft in 1939

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

During the late 1930s Moore participated in a number of high profile exhibitions including Cubism and Abstract Art, curated by Alfred H. Barr at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1936. Despite the increasingly polarised artistic allegiances that had led to the collapse of Unit One, Moore continued to exhibit in a number of different contexts, alongside artists making quite different types of work. In 1936 he joined a group of surrealist artists led by painter Roald Penrose and became honorary treasurer of the organising committee for the International Surrealist Exhibition which took place at the New Burlington Galleries London, in June that year. Here he exhibited sculptures alongside works by Arp, Giacommetti, Brancusi, Calder, and Dalí (fig.19). He continued to exhibit in exhibitions of surrealist art until 1940 (fig.20). At the same time he also exhibited alongside constructivist artists. He exhibited alongside Nicholson and Mondrian, for example, in an exhibition called Abstract and Concrete in 1936, and he also contributed to Axis, a literary and artistic journal which sought to place British art within an international context. In 1937, Axis published a book of artists’ statements entitled The Painter’s Object, edited by Myfanway Piper. Moore’s contribution was an article called ‘The Sculptor Speaks’, which had recently been published in the Listener. In his article Moore tried to diminish the importance of the divisions between the different groupings: ‘The violent quarrel between the abstractionsits and the surrealists seems to me quite unnecessary. All good art has contained both abstract and surrealist elements, just as it has contained both classical and romantic elements – order and surprise, intellect and imagination, conscious and unconscious’.52

International Surrealist Exhibition at the New Burlington Galleries, London showing two sculptures by Moore, 1936

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.19

International Surrealist Exhibition at the New Burlington Galleries, London showing two sculptures by Moore, 1936

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

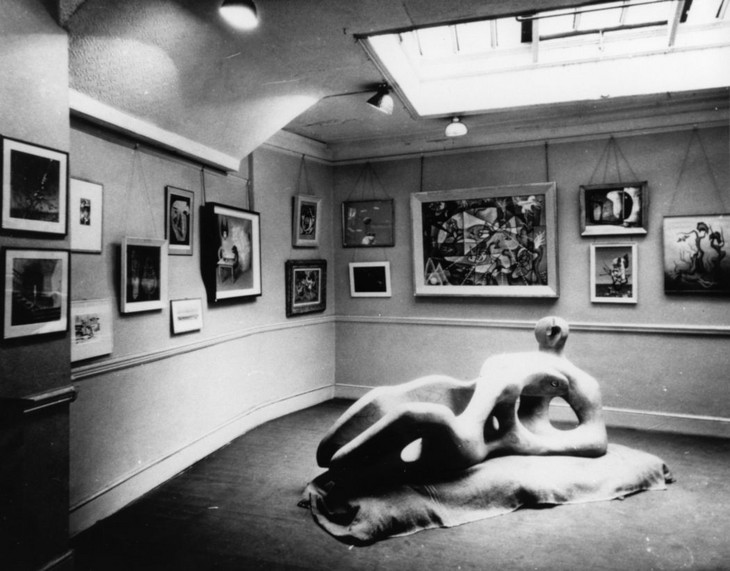

Surrealism Today, Zwemmer Gallery, London, showing Reclining Figure 1939 on the floor in 1940

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.20

Surrealism Today, Zwemmer Gallery, London, showing Reclining Figure 1939 on the floor in 1940

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Moore went on to contribute to Circle: International Survey of Constructive Art in 1937, edited by Nicholson, Naum Gabo and the architect Leslie Martin. Its aim was to demonstrate the positive contributions the arts and humanities could make to all areas of life, and it included essays by mathematians and scientists as well as artists and urban planners. According to Berthoud, ‘the idea of art as a moral, and indeed spiritual, activitiy’, which was at the core of Circle’s beliefs, ‘was to remain with Moore throughout his career’,53 though only one issue of the journal was produced.

In the years immediately preceding the Second World War Moore, with the help of Meadows, made some of his most important works including a series of large elm figures, with limbs and torsos opened out and pierced (figs.21, 22). In 1937 Moore explained his use of the ‘hole’, or space, within solid forms:

The first hole made through a piece of stone is a revelation. The hole connects one side to another, making it immediately more three-dimensional. A hole can have as much shape-meaning as a solid mass. Sculpture in air is possible, where the stone contains only the hole, which is the intended and considered form. The mystery of the hole – the mysterious fascination of caves in hillsides and cliffs.54

Recumbent Figure, with a large ‘hole’ in its belly and fused limbs, was to become one of his most well-known sculptures but was important for another reason: it was through this work that Moore secured his life-long friendship with Sir Kenneth Clark, then Director of the National Gallery of Art. Although Clark had bought one of Moore’s drawings from his Warren Gallery exhibition in 1928, it is thought that Clark only entered Moore’s life in 1938.55 After the first buyer of Recumbent Figure was declared bankrupt and had to return the sculpture, Clark arranged for it to be purchased by the Contemporary Art Society in March 1939, which in turn presented it to the Tate Gallery in April 1939.

At the outbreak of the war Moore was at Burcroft preparing for a solo exhibition at the Leicester Galleries in November 1939. The exhibition was cancelled, and when Chelsea School of Art was evacuated to Northamptonshire, Moore ceased teaching. On 8 October 1939 Moore wrote to his friend, poet Arthur Sale:

Henry Moore OM, CH 1898–1986

Recumbent Figure 1938

Green Hornton stone

object: 889 x 1327 x 737 mm, 520 kg

Tate N05387

Presented by the Contemporary Art Society 1939

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.21

Henry Moore OM, CH

Recumbent Figure 1938

Tate N05387

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

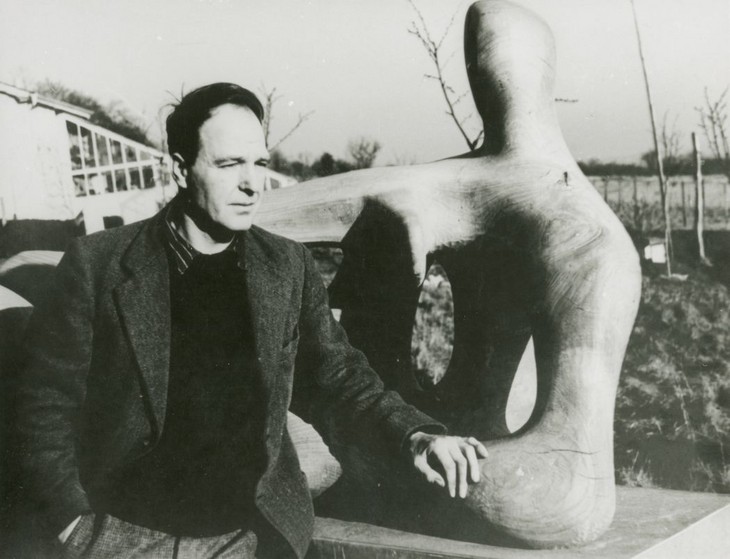

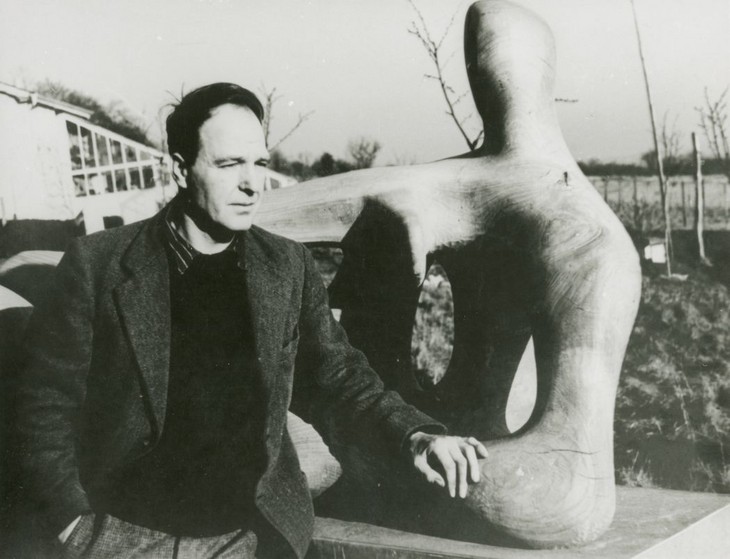

Henry Moore with Reclining Figure 1939 at Burcroft in 1939

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.22

Henry Moore with Reclining Figure 1939 at Burcroft in 1939

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

At the outbreak of the war Moore was at Burcroft preparing for a solo exhibition at the Leicester Galleries in November 1939. The exhibition was cancelled, and when Chelsea School of Art was evacuated to Northamptonshire, Moore ceased teaching. On 8 October 1939 Moore wrote to his friend, poet Arthur Sale:

I'm going on working just as usual – that seems the most sensible thing to do, besides being what I want to do. When war broke out I was in full swing with work, trying to get a satisfactory lot done for the sculpture exhibition I had fixed at the Leicester Galleries this November. Lately I’ve been making ideas and figures for metal and in the last five or six weeks I’ve modelled in wax and then cast into lead, some eight or nine things. So the war doesn’t so far seem to have interfered with work. But of course the war atmosphere might get closer and more intense, its sure to, – and for how long it will be possible then to concentrate well enough for proper work, who can tell. But in the meantime we consider ourselves lucky that we can see financially 4 or 5 months ahead, and I can quietly go on working here ... At present I’m a couple of months over the military service age. But if the war goes on for any length of time, the limit won’t stay for long at 41. I was in the trenches in the last war, and so all the more don’t want to shoot or be shot at, again. And like every other sane person I hate war and all it stands for. But I can’t say with complete certainty that there aren’t some things I might find myself ready to fight for, and so I can’t call myself a wholy [sic] consistent conscientious objector. I'd be glad if I could, for I respect greatly the real pacifist point of view, and I’m glad to know that you are a C.O., and will have the courage to remain so. I think this war need not have come – if we’d had a better government and a different attitude to Russia. Now it’s here, I think its more or less the same set up as in 1914, that is it’s largely an Imperialist war again, but with this difference that in place of the Kaiser and the old German militarists there is the more reactionary and barbaric regime of Hitler and the Nazi party. And now the war’s started, – if Fascist Germany wins then I think most of the civil liberties in Europe would go: there’d be less freedom of expression and a poor chance for the existence of the kind of painting, sculpture, literature, music, architecture, that I believe in:– Although no one can say there’s democracy in England in the real sense of the word, and although British Imperialism has a pretty bloody record, I hate Fascism and Nazism and all its aims and ideology so intensely, that I don’t think I could refuse to help in in [sic] trying to prevent it from being victorious. However when the time comes that I’m asked, or have got to do something in this war, I hope it will be something less destructive than taking part in the actual fighting and killing.56

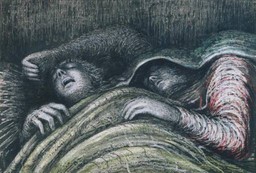

In 1940 a number of events changed the direction of Moore’s career. It had become increasing difficult to travel around Kent, and the Moores found their cottage fell within an area of Kent designated as a restricted zone, curtailing free movement. They therefore moved back to their small studio appartment in Hampstead. One evening in September 1940 Moore and his wife were returning home on the Underground, after meeting friends for dinner in the West End:

As a rule I went into town by car and hadn’t been by tube for ages. For the first time that evening I saw people lying on the platforms at all the stations we stopped at. When we got to Belsize Park we weren’t allowed out of the station for an hour because of the bombing. I spent the time looking at the rows of people sleeping on the platforms. I had never seen so many reclining figures, and even the train tunnels seemed to be like the holes in my sculpture. Amid the grim tension, I noticed groups of strangers formed together into intimate groups and children alseep within feet of the passing trains.57

Moore created some drawings depicting the shelter scenes and showed them to Kenneth Clark. Clark was chairman of the War Artists’ Advisory Committee (WAAC), which had been set up in November 1939, and he immediately invited Moore to become an official war artist. Moore, who had previously declined the same intivation, now accepted and set to work on what were to become known as his ‘shelter drawings’ (see fig.23).

Around this time Moore found that he had to move home again. Following a weekend away visiting friends, the Labour MP Leonard Matters and his wife, in Hertfordshire, the Moores returned to Hampstead to find their home cordoned off. The studio had suffered a bomb blast and was uninhabitable. The Moores returned to Hertfordshire and stayed with the Matters, who encouraged them to find accomodation nearby. On 20 September 1941 Henry and Irina moved into Hoglands, a cottage in the hamlet of Perry Green, where they would live for the rest of their lives.

Graham Sutherland, John Piper, Henry Moore and Kenneth Clark at Temple Newsam, Leeds in 1941

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.24

Graham Sutherland, John Piper, Henry Moore and Kenneth Clark at Temple Newsam, Leeds in 1941

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Curt Valentin and Henry Moore in the Upper Studio at Hoglands, Perry Green in 1950

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.25

Curt Valentin and Henry Moore in the Upper Studio at Hoglands, Perry Green in 1950

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Henry Moore

Madonna and Child 1943–4

Hornton Stone

Church of St Matthew, Northampton

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.26

Henry Moore

Madonna and Child 1943–4

Church of St Matthew, Northampton

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

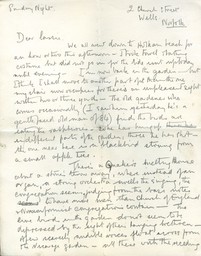

When I was first asked to carve a Madonna and Child for St Matthew’s, although I was very interested I wasn’t sure whether I could do it, or whether I even wanted to do it. One knows that religion has been the inspiration of most of Europe’s greatest painting and sculpture, and that the church in the past has encouraged and employed the greatest artists; but the great tradition of religious art seems to have got lost completely in the present day, and the general level of church art has fallen very low ... Therefore I felt it was not a commission straightway and light-heartedly to agree to undertake, and I could only promise to make notebook drawings from which I would do small clay models, and only then should I be able to say whether I could produce something which would be satisfactory as sculpture and also satisfy my idea of the Madonna and Child theme as well ... I began thinking of the Madonna and Child for St. Matthew’s by considering in what ways a Madonna and Child differs from a carving of just a ‘Mother and Child’ – that is, by considering how in my opinion, religious art differs from secular art ... It’s not easy to describe in words what this difference is, except by saying in general terms that the Madonna and Child should have an austerity and a nobility, and some touch of grandeur (even hieratic aloofness) which is missing in the everyday ‘Mother and Child’ idea. Of the sketches and models I have done, the one chosen has, I think, a quiet dignity and gentleness.59

Henry Moore

Maquette for Family Group 1945

Tate N05606

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.27

Henry Moore

Maquette for Family Group 1945

Tate N05606

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

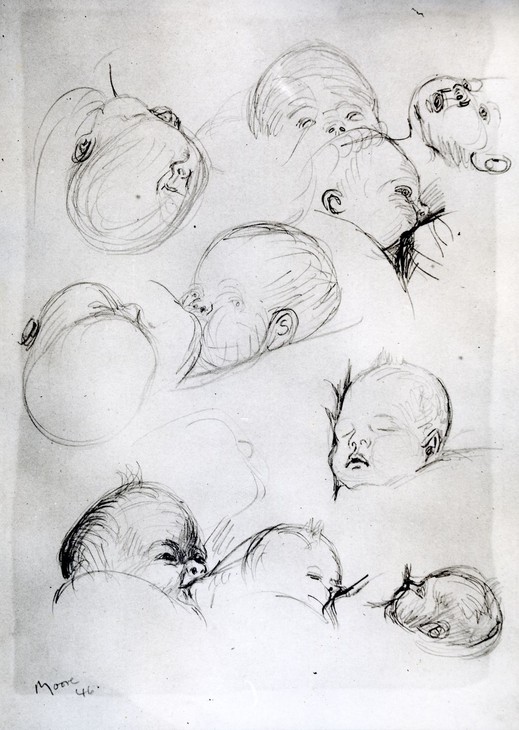

Henry Moore

Studies of the Artist's Child 1946

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.28

Henry Moore

Studies of the Artist's Child 1946

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

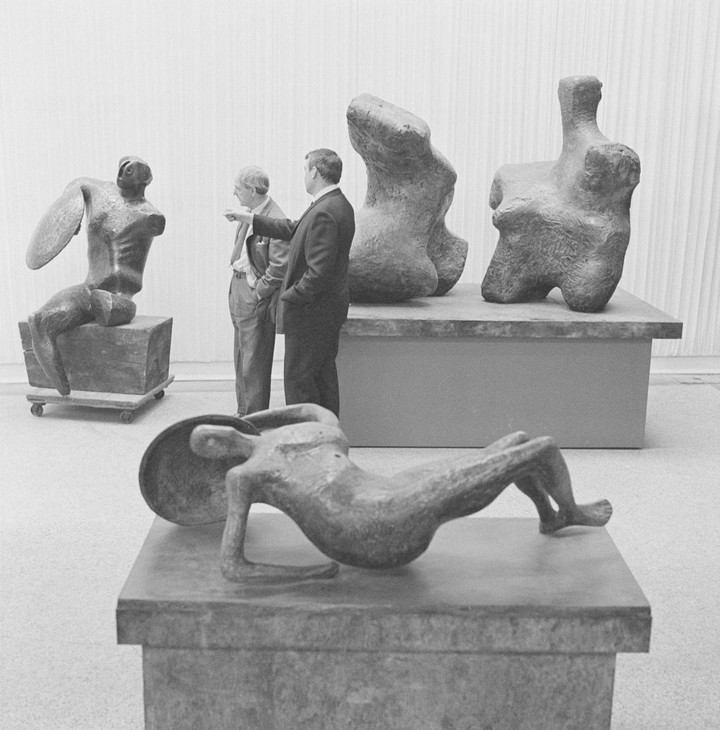

Installation view of Moore's retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, December 1946

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Soichi Sunami, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.29

Installation view of Moore's retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, December 1946

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Soichi Sunami, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

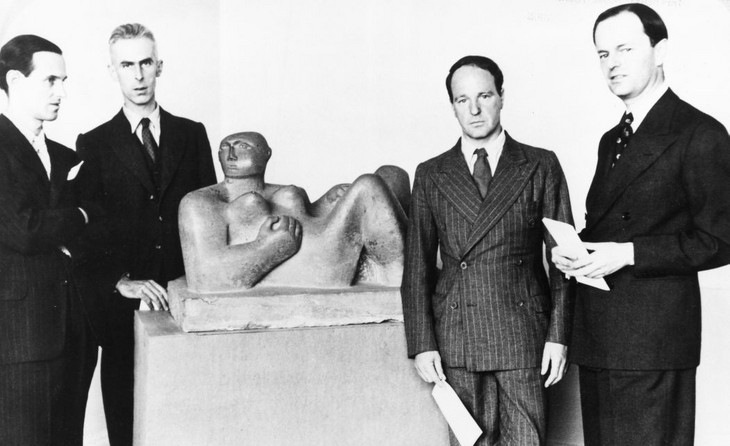

Moore standing next to Pat Strauss of the London County Council and Aneurin Bevan, Minister for Health, with Three Standing Figures 1948 at the Battersea Park Open Art Sculpture Exhibition 1948

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: The Henry Moore Foundation archive

Fig.30

Moore standing next to Pat Strauss of the London County Council and Aneurin Bevan, Minister for Health, with Three Standing Figures 1948 at the Battersea Park Open Art Sculpture Exhibition 1948

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: The Henry Moore Foundation archive

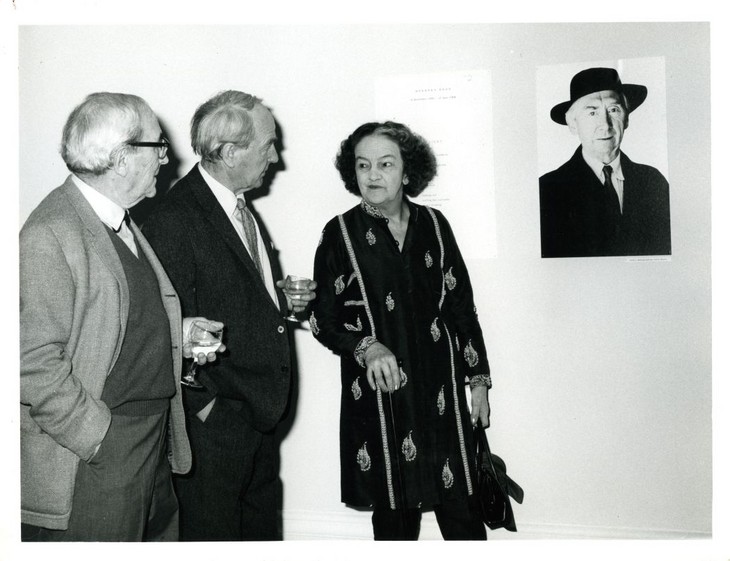

John Rothenstein (right) escorting Luigi Einaudi (centre), President of Italy, in the exhibition of Henry Moore's work in the British Pavilion at the Venice Biennale, 1948

© British Council Archives, Kew

Fig.31

John Rothenstein (right) escorting Luigi Einaudi (centre), President of Italy, in the exhibition of Henry Moore's work in the British Pavilion at the Venice Biennale, 1948

© British Council Archives, Kew

Although Moore had served a full term as a Tate trustee from 1941 to 1948, when a seat became vacant in 1949 it was suggested that he should be reappointed. Sir Jasper Ridley, Chairman of the Tate Board of Trustees, wrote to Anthony Bevir, the Permanent Secretary to the Prime Minister’s Office, that ‘Henry Moore was a conspicuously useful Trustee on any topic that arose, whether in judgement or administration’.66 On 12 July 1949 Bevir duly wrote to Moore saying, ‘There is a vacancy on the Board of the Tate Gallery, and the Prime Minister has asked me to enquire whether you would be prepared to serve as a Trustee’.67 Moore readily agreed and sat on the board of the gallery until 1956. During this time, Moore advocated the purchase of sculpture by Alexander Calder, Naum Gabo and David Smith, among others.68

Photograph taken in 1949 of two full-size plaster versions of Family Group

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.32

Photograph taken in 1949 of two full-size plaster versions of Family Group

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

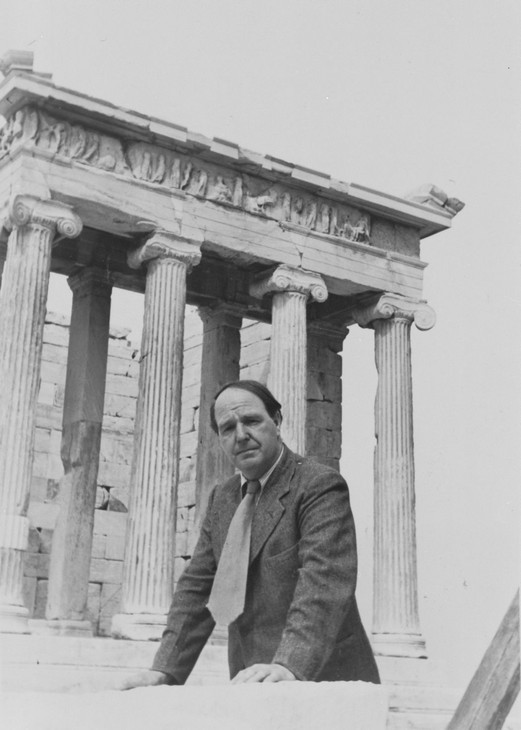

In 1949 Wakefield City Art gallery hosted the largest exhibition of Moore’s work to date. The show was curated by Moore’s friend and fellow Yorkshireman, Philip Hendy, who that year succeeded Kenneth Clark as director of the National Gallery. The exhibition was largely successful and, following its display at Manchester City Art Gallery, toured Europe. The British Council took the exhibition to most of Europe’s largest cities, including Paris, Amsterdam and Hamburg. In March 1951 a version of the show was also mounted at the Zappeion Gallery in Athens, which gave Moore, then aged fifty-two, the opportunity to visit the home of classical sculpture (fig.33). Struck by the light in Greece and what he saw as the theatricality of its ancient monuments, he wrote enthusiastically to Kenneth Clark: ‘the Acropolis is wonderful – more marvellous than ever I imagined – The Parthenon against a blue sky – the sunlight and the scale it gets against the distant mountains can’t be given by any photograph – It’s the greatest thrill I’ve ever had’.69 Moore’s exhibition in Athens was visited by over 34,000 people and was a record attendance for any exhibition of contemporary art arranged by the British Council.70 W.G. Tatcham of the British Council in Athens, however, reported to his London colleagues that, ‘of course there has been controversy. I understand that one paper wrote that it was impertinent “for the barbarians from a foggy island to send these objects to the home of the greatest sculptors ever born”, or words to that effect’.71 Nonetheless, the consequence of Moore’s visit to Greece was that Moore embraced the classical subject of the draped woman, creating a series of reclining females throughout the 1950s (fig.34).

Henry Moore in Greece, 1951

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.33

Henry Moore in Greece, 1951

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Henry Moore

Draped Reclining Woman 1957–8

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.34

Henry Moore

Draped Reclining Woman 1957–8

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Henry Moore

Reclining Figure 1951 installed on the South Bank during the Festival of Britain 1951

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.35

Henry Moore

Reclining Figure 1951 installed on the South Bank during the Festival of Britain 1951

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

The ‘Festival Reclining Figure’ is perhaps my first sculpture where the space and the form are completely dependent on and inseparable from each other. I had reached the stage where I wanted my sculpture to be truly three-dimensional. In my earliest use of holes in sculpture, the holes were features in themselves. Now the space and form are so naturally fused that they are one.72

During the Festival a bronze cast was exhibited in front of the Land of Britain pavilion on the South Bank in London, and was criticised by David Sylvester, who wrote in the Studio:

One suspects that Moore has conceived this work purely as a sculptural object, not as an image, because the forms, considered as signs, are either conventional or arbitrary. The head is just as much a cliché as are the heads in official portraits by Royal Academicians. The legs have no connexion with the structure ... This latest addition, then, to Moore’s long series of ‘opened-out’ reclining figures has too little contact with life to carry the imaginative conviction and dramatic power of its predecessors. And, after all, it is not surprising that his handling of this theme should have reached the stage of empty, if impressive, virtuosity, since he has been exploiting it now for twenty years.73

During the Festival Moore also had an exhibition at the Tate Gallery. In the foreword to the exhibition catalogue, Philip James proclaimed Moore to be ‘our greatest living sculptor’, a statement that drew negative reactions in the press. Riding a crest of a wave of institutional support, Moore was also the subject of the first film on a living artist to be broadcast by the BBC. Directed by John Read (son of Herbert Read), the film followed Moore’s creative processes and made a detailed study of the development of the festival Reclining Figure.74 Transmitted on 30 April 1951, the film won a prize at the Venice Film Festival that summer.

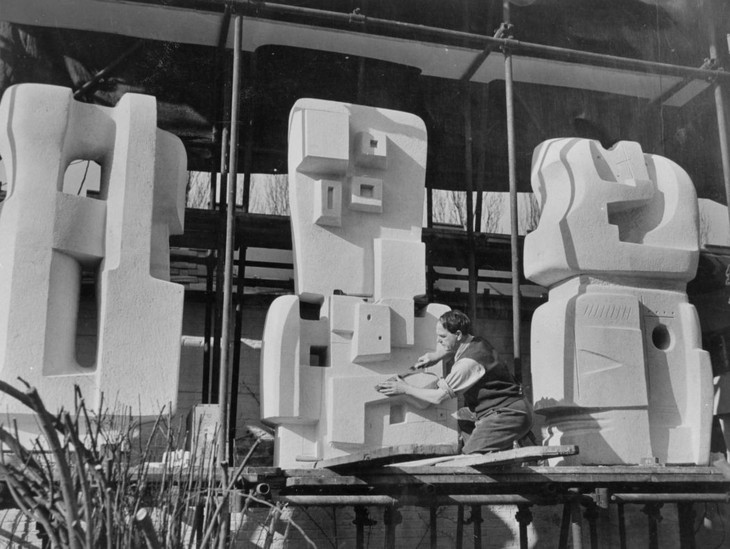

Moore working on the Time-Life Screen, 1952–3

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.36

Moore working on the Time-Life Screen, 1952–3

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Henry Moore OM, CH 1898–1986

Girl 1931

Ancaster stone

object: 737 x 368 x 273 mm

Tate N06078

Purchased 1952

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.37

Henry Moore OM, CH

Girl 1931

Tate N06078

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore and Rufino Tamayo at the Pyramid of the Feathered Serpent, Xochicalco, Mexico, 1953

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.38

Henry Moore and Rufino Tamayo at the Pyramid of the Feathered Serpent, Xochicalco, Mexico, 1953

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

In 1955 Moore was commissioned to create an architectural relief for an extension to the Bouwcentrum in Rotterdam (fig.39). Although Moore disliked sculpture being subsumed by architecture, the opportunity to work with the medium of brick and the scale of the project stimulated him and inspired a series of standing organic relief plaques and standing forms, including the three Upright Motives in Tate’s collection (Tate T02274, T02275 and T02276).

Henry Moore

Wall Relief 1955

Brick Bouwcentrum, Rotterdam

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.39

Henry Moore

Wall Relief 1955

Brick Bouwcentrum, Rotterdam

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Moore’s position as a leading figure in British culture was cemented in June 1955, when he was named a Companion of Honour (CH) in the Queen’s Birthday Honours List. The honour was, and remains, particularly prestigious, as it can only be held by fifty British people at any one time, and is of a higher rank than a Knighthood. To many the honour was long overdue, but in fact Moore had previously turned down a Knighthood in December 1950.

In May 1955 Moore was approached to create a large-scale sculpture for the new United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (Unesco) headquarters being built in Paris. The building was being designed by architect Marcel Breuer, who Moore had known from his Hampstead days in the 1930s, and the critic Herbert Read sat on the committee established to commission artworks for the premises. Major commissions were also awarded to Picasso, Calder, Arp and Noguchi. Moore went to Paris in November to discuss the commission and was given a delivery deadline of mid-1958. In August 1956 he wrote to Read: ‘It’s not going to be an easy commission. So far what ideas have come (some of them) might work out as sculpture purely for myself, but no one idea has turned up to concentrate on yet ... I have given up all my other work ... [but] the size and importance of the commission is such that I can’t expect even the preliminary stages to be quick’.78

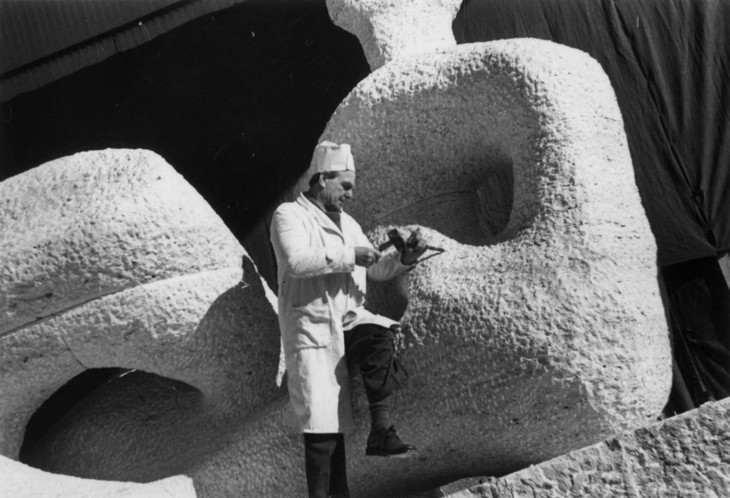

In early 1957 Moore took three maquettes to Paris to be judged by representatives of the architects and the art advisory committee. All independently selected the same work, which fortunately was also Moore’s favourite. The decision was unanimous and Moore had the go-ahead to carve his Reclining Figure in travertine marble (fig.40). The marble was supplied by an Italian firm called Henraux, located at the foot of the Carrara mountains. Artisans at Henraux did much of the initial roughing out of the sculpture, although from the summer of July 1957 until early 1958 Moore had regular trips of three to four weeks duration. Nonetheless, the sculpture was not installed in Paris until October 1958 in time for inauguration of the Unesco building in November. The sculpture was by far the largest work Moore had created to date. In the years that followed Moore received numerous public commissions, and created works for public plazas on a much larger size than before.

Henry Moore OM, CH 1898–1986

King and Queen 1952–3, cast 1957

Bronze

object: 1640 x 1390 x 910 mm

Tate T00228

Presented by the Friends of the Tate Gallery with funds provided by Associated Rediffusion Ltd 1959

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.41

Henry Moore OM, CH

King and Queen 1952–3, cast 1957

Tate T00228

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Moore’s dedication to the Tate was also demonstrated in February 1959. Following the death of the collector and publisher, E.C. Gregory, his executors, chaired by solicitor Leonard Wade, asked his friends Henry Moore, Herbert Read and poet T.S. Eliot to act as an art advisory committee, providing advice on the distribution of his personal collection of paintings, sculptures and non-western artefacts. Named beneficiaries, including the Tate Gallery, the Arts Council and the University of Leeds, were to have the opportunity to select works from the estate, and the remainder was to be sold at Sotheby’s auction house. Upon receiving the inventory of Gregory’s collection, the Tate trustees were given the first choice to select the six works promised to the gallery under the terms of Gregory’s will. On the guidance of Moore, Read and Eliot, the executors also provided Tate the opportunity to purchase a further twelve works prior to the auction sale. Although it was noted that Moore might have a conflict of interest as he had works in Gregory’s collection and was a former Tate Gallery trustee, he nonetheless was asked to draw up a list of appropriate purchases, including prices, for Tate in his capacity as art advisor to the Gregory estate. Following Gregory’s life-long example of supporting younger artists, Moore’s proposed acquisition list included works by the sculptors Reg Butler, Anthony Caro, Hubert Dalwood and Eduardo Paolozzi, and it was duly accepted by the Tate trustees.81 In a letter to Moore, Sir John Rothenstein, Director of the Tate Gallery wrote that the trustees, ‘asked me to tell you how deeply grateful they are for all the trouble which you have given yourself in order to make this as satisfactory as possible’, concluding, ‘Looking back over this letter I feel that, having richly earned a period of honourable retirement you are being just as much involved in the Gallery’s affairs as you were when you were a Trustee’.82

By the end of the 1950s Moore had dramatically changed his working methods compared to how he worked prior to the war. Studios were built or enlarged in the grounds of Hoglands, and a team of assistants enlarged small plaster maquettes that were then sent to bronze foundries for casting in editions. Moore found that he could easily sell small versions in bronze of his large-scale commissions, thereby ensuring a steady income with little or no extra work. In November 1960 Moore, who had not had a solo exhibition in England for five years, had an exhibition of recent work at the Whitechapel Art Gallery (fig.42), curated by Bryan Robertson. Reviews were mixed. Following an appreciative discussion of Moore’s large-scale reclining figures, including Two-Piece Reclining Figure No.2 (Tate T00395), Nevile Wallis wrote in the Observer that ‘the vaulting imagination of this work ... naturally sharpens criticisms of those ingenuities where stylisation seems employed rather for its own sake than as a vehicle of serious emotion’.83 In Art International the critic Lawrence Alloway argued that Moore’s work failed because of its ambitions to represent a universal humanism. ‘Obviously out of the highest motives, Moore is hoping to give his public sculptures a worthy message, a stirring content’, but for Alloway it was no longer possible to speak of universal values or truths. A person could only speak of his or her own time and place, he believed, and observed that ‘Moore seems dissatisfied with what he can reach from his own situation. As a result all he offers, despite his ambition, is a sculpture of empty Virtues’.84

Henry Moore and Bryan Robertson in the Whitechapel Art Gallery, London, December 1960– January 1961

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.42

Henry Moore and Bryan Robertson in the Whitechapel Art Gallery, London, December 1960– January 1961

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Without the eloquence of Alloway’s thoughtful criticism, the sculptor Anthony Caro also questioned Moore’s apparent unquestioned dominance within British sculpture in his response to the Whitechapel show. Caro, who had worked as a studio assistant for Moore from 1951 to 1953, wrote in the Observer that although Moore had paved the way for the next generation of artists, he ‘has paid heavily for his stardom’: ‘my generation abhors the idea of a father-figure, and his work is bitterly attacked by artists and critics under forty when it fails to measure up to the outsize scale it has been given’.85 Caro’s objections to Moore’s work were based on the uncritical nature of the process by which Moore’s tiny maquettes were scaled-up, in his view, regardless of whether the sculptural form could sustain such enlargement.

Despite these criticisms, and following negotiations carried out over the course of the previous three years, the Friends of Tate acquired six sculptures by Moore for the gallery in December 1960. All the sculptures were acquired directly from the artist and were selected as representative examples of Moore’s various styles and subjects to date. They were Composition 1932 (Tate T00385); Stringed Figure 1938/60 (Tate T00386); Reclining Figure 1939 (Tate T00387); Helmet Head No.1 1950 (Tate T00388); Mother and Child 1953 (Tate T00389); and Working Model for Unesco Reclining Figure 1957 (Tate T00390).

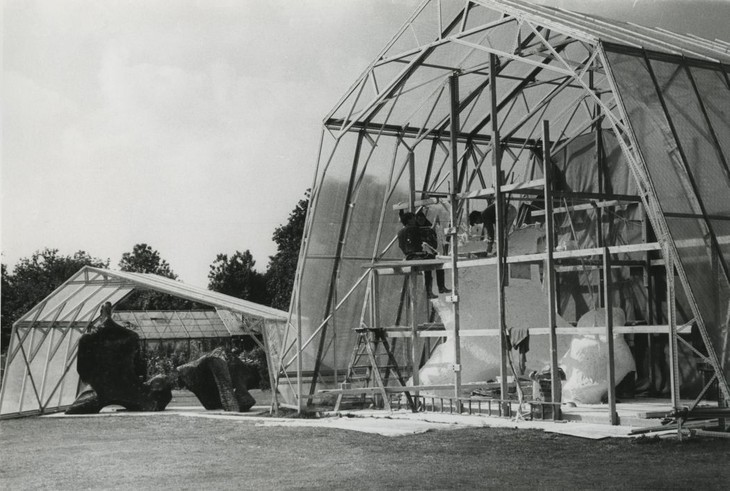

Moore’s status grew ever greater in the 1960s, and he spent much of the decade working on large-scale public commissions. The first of these was a sculpture for a new arts and cultural centre being built in New York City. In December 1961 Moore was approached to create a sculpture that would be sited in a water pool the size of a tennis court in front of the Vivian Beaumont Theatre and Library Building. The fee for the commission was $240,000, which was to cover all costs, including casting and shipping. Moore was interested in the idea of a sculpture reflected in water and accepted the commission. During the summer of 1962 Moore made some maquettes and tested them out in a small swimming pool in the garden at Hoglands. He settled on a two-piece figure. At 8.5 meters long and 5.1 meters high, Reclining Figure was Moore’s largest sculpture to date and in order to build a full-size plaster model, from which a bronze version could be cast he had to erect a temporary studio (fig.43). Once the plaster was complete, it was cut up into sixty-five smaller pieces and shipped to the Noack foundry in West Berlin, where the pieces were cast and then welded together. The job took the foundry over a year to complete, and the work was shipped to New York in July 1965. When the Vivian Beaumont Theatre and Library Building was opened in August, a group of artists picketed the sculpture with placards saying ‘Insult to American Artists – No Moore’.86

During this period Moore was beginning to think about his legacy, and in a letter dated 14 August 1964 Tate’s Director John Rothenstein wrote to Moore, stating,

You have spoken to me on a number of occasions about the idea which you have in mind about bequeathing certain of your works to the Tate ... My reason for writing to you now is that my last Board meeting takes place on the 17th next month ... I should be very proud if the trustees could be informed then, even if only in somewhat general terms, of your splendid intention; indeed I should feel this to make a wonderful conclusion to my Directorship.87

Plaster versions of Working Model for Reclining Figure (Lincoln Centre) 1963–5 and Reclining Figure 1963–5 at Hoglands c.1964

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.43

Plaster versions of Working Model for Reclining Figure (Lincoln Centre) 1963–5 and Reclining Figure 1963–5 at Hoglands c.1964

The Henry Moore Foundation

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

A meeting between Moore and Rothenstein took place on 15 September 1964, and although what was said was not recorded, Rothenstein was able to make his desired announcement at his final meeting with the trustees. On 18 September he wrote to Moore, saying ‘yesterday I reported to the Board in accordance with our agreement on Tuesday, your intention of making a bequest of a number of your works to the gallery’.88 Rothenstein concluded his directorship of the Tate as he wished, announcing Moore’s intention to give the gallery a selection of his works, however he could not have foreseen the hurdles which his successor Norman Reid would face, not only in the form of opposition at home but also from competition for Moore’s work from abroad.89

The unveiling of Three Way Piece No.2: Archer 1964–6 in Nathan Phillips Square, Toronto, 27 October 1966

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: The Globe and Mail, Toronto, Canada, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.44

The unveiling of Three Way Piece No.2: Archer 1964–6 in Nathan Phillips Square, Toronto, 27 October 1966

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: The Globe and Mail, Toronto, Canada, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

In February 1967 it was announced in the British press that Moore had pledged a gift of sculptures to the nation. Rothenstein and Reid had both realised that, at its present size, the gallery would be unable to display Moore’s large gift of between twenty and thirty sculptures, and so had left open the date of when the gift would be made. Nonetheless, some commentators questioned whether the sculptures should be housed at the Tate at all, with one correspondent in the Times suggesting the creation of a ‘Moorehenge’ on Salisbury Plain.90

While these debates took place in the British press, Moore travelled to Toronto to see Archer and attended a series of celebratory events in March 1967. It was a trip Moore thoroughly enjoyed and it was during a reception in Moore’s honour that the idea of a Moore Gallery in Toronto was first mooted. The idea was quickly picked up by the city’s leading philanthropists, politicians, and significantly, Samuel J. Zacks, president of the Art Gallery of Ontario, and its director William Withrow. A local businessman approached Moore about the possibility of the city acquiring more of his works and Moore is reported to have responded: ‘Well, you know, I’m British ... and I feel I own a debt to the country I come from ... however, I don’t think the Tate is going to be big enough to handle all my work. There may be something remaining, and with regard to that, perhaps something might be possible’.91 On 15 March Moore met with Zacks and Withrow to discuss the possibility of making a number of acquisitions, and the next day Moore was quoted in the Toronto Daily Star as saying, ‘I’d like the sculpture to go to London for sentimental reasons, but offers from somewhere else might make help the Tate Gallery make up its mind’.92

Moore’s statement had an effect and in April 1967 the British Prime Minister, Harold Wilson, announced the government’s pledge of £200,000 for the building of new galleries at Tate to house the Henry Moore gift. His announcement was made at the Royal Academy banquet, and the sum was dependent upon the Tate trustees raising a similar sum for the completion of a new north-east wing extension, plans for which were already underway. However, as Berthoud has pointed out, ‘the way he [Wilson] had blurred together the display of the Moores and the funding of the Tate extension was to prove very troublesome’.93 What was unclear was that the sum of £200,000 was in addition to funds to be provided by the Treasury for the Tate Gallery extension: to many it seemed as though a Moore annexe was about to be built at the Tate.

The negative effect of Wilson’s announcement was made explicit in a letter written by forty-one British artists and published in the Times on 26 May. In the letter, the signatories queried whether large display areas within a public gallery should be reserved for a single artist, suggesting that such preferential treatment would have a negative impact on the exhibitionary opportunities of others.94 A few days after the publication of the artists’ letter in the Times, Samuel Zacks wrote to Moore stating that the Art Gallery of Ontario would be interested in establishing a Henry Moore Gallery:

I would like to point out that a handsome Moore Gallery and sculpture court on the site of our own gallery would be most meaningful, not only to Toronto, but to the whole continent which holds your work in the highest esteem. In the city there are close to one hundred pieces of your works [in private collections], and many would be donated to the gallery and added to the ones you might donate, so we could assemble a very imposing group of your creations.95

As Berthoud observed, ‘the contrast between supportive, enthusiastic Canadians and ungrateful, niggardly Britons could scarcely have been more heavily underlined. The Tate did not get less as a result, but Moore’s desire to be generous to Toronto was reinforced’.96

Having been announced in the press, Moore’s gift to the Tate had attracted the attention of a number of philanthropists and interested parties from beyond the gallery, including property developer Max Rayne and Lord Perth, First Crown Estate Commissioner, who proposed to Moore a number of alternative options for housing the Tate gift. These included a Henry Moore Museum, a smaller pavilion for plasters and maquettes and a sculpture park in Regents Park, London. By October 1967 the Tate’s Director and Board of Trustees were in a muddle over whether or not a separate Henry Moore Museum, run by the Tate, was wanted, or whether the gift could be incorporated into the existing plans for the new extension. Throughout late 1967 and early 1968 the chairman and deputy chairman of the Tate’s trustees, Lousada and Robert Sainsbury, made regular visits to Henry Moore aiming to keep his mind focused on his gift to Tate. It was the trustees’ belief that a separate Moore museum should not be constructed, that the ‘best’ works should remain in the UK and that Moore’s long-term reputation would be best served by his work being seen within the context of the British national collection.

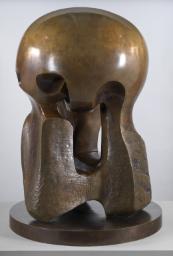

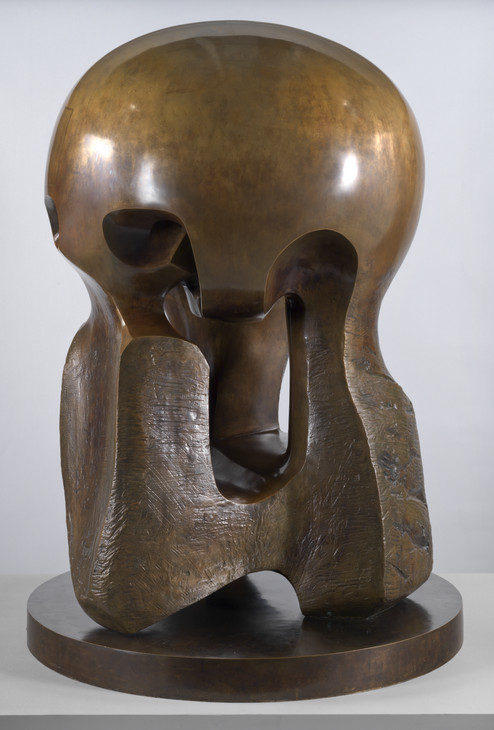

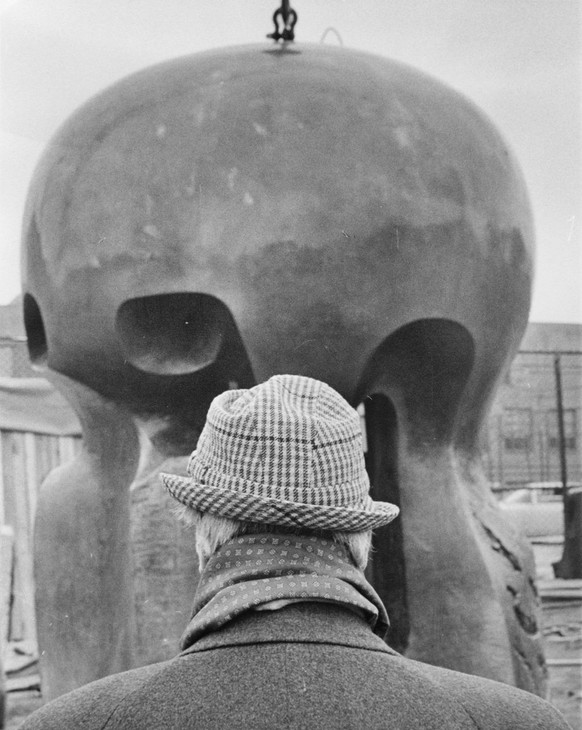

However, in early December 1967, Moore visited Toronto again in order to discuss the proposals in more detail on his return from the unveiling of his large-scale sculpture Nuclear Energy at the University of Chicago. Some years before, in November 1963, Moore had been approached by Professor William McNeill, head of the History department at the University of Chicago enquiring whether he would be interested in creating a work commemorating the physicist Enrico Fermi. On 2 December 1942 Fermi had achieved the world’s first controlled nuclear chain reaction in the University’s laboratories, and to mark the twenty-fifth anniversary of the event the University was seeking an appropriate tribute. McNeill told Moore that he hoped the sculpture would be ‘charged with high hope and profound fear, just as every triumphant breakthrough has always been’.97 Moore replied on 2 December 1963, ‘I realize what a tremendous happening that was, and that a monument for such a triumphant breakthrough may be called for. It seems an enormous event in man’s history, and a worthy memorial for it would be a great responsibility and not easy to do. However, it would be a great challenge and something I might like to consider’.98 That month McNeill and two other delegates from the University visited Hoglands, where they were shown a small maquette for a domed sculpture. Although nothing was formally agreed, Moore decided to go ahead and enlarge the sculpture and if the Chicago committee liked the larger work they could proceed with the commission. A four-foot working model of the sculpture was made plaster in the summer of 1964 and then cast in bronze in early 1965 (fig.45). On seeing the photographs of the smaller sculpture the University committee enthusiastically agreed to purchase the sculpture. The bronze was cast by Noack and shipped to Chicago in August 1967. Moore arrived in Chicago on 29 November to oversee the sculpture’s installation and to attend the inauguration of the sculpture at 3.36pm on 2 December, the exact time of Fermi’s experiment (fig.46).

Henry Moore OM, CH 1898–1986

Atom Piece (Working Model for Nuclear Energy) 1964–5, cast 1965

Bronze

object: 1270 x 920 x 920 mm

Tate T02296

Presented by the artist 1978

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.45

Henry Moore OM, CH

Atom Piece (Working Model for Nuclear Energy) 1964–5, cast 1965

Tate T02296

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore in front of Nuclear Energy at the University of Chicago, 2 December 1967

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.46

Henry Moore in front of Nuclear Energy at the University of Chicago, 2 December 1967

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

In July 1968 Moore celebrated his seventieth birthday with a solo exhibition at the Tate Gallery, curated by David Sylvester. There had been some debate over whether or not the exhibition should be the inaugural exhibition at the newly built Hayward Gallery but the Tate was decided upon and attracted 124,081 people in sixty-seven days. At the celebratory dinner the collector Joseph Hirshhorn presented Tate’s Director Norman Reid with a cheque for $30,000; he stated, ‘They can do anything they like [with it] ... Henry is one of the greats of the twentieth-century, and a lovely, simple human being. I wanted to do something in his name’.99 During the exhibition, on 19 July 1968, Locking Piece 1963–4 (Tate T02293) was erected near to the Tate Gallery in a newly designed garden and riverside walkway on Millbank by the River Thames. Although it would later be included in Moore’s gift to the Tate, it was then on loan to Westminster County Council.

While the Tate Gallery was celebrating Moore’s birthday, rumours abounded in the Canadian press that Moore had decided to leave his collection to Canada because the Tate was unable to house it properly. Under pressure from the Canadian press for clarification, Reid spoke to Moore in October 1968. Moore confirmed that although he planned to give Canada some of his original plasters, ‘there was no intention of in any way altering his gift to the Tate’.100 Nonetheless, on 9 December 1968 Moore wrote to Edmund Bovey, President of the Art Gallery of Ontario, indicating his ‘firm intention to donate to the Art Gallery of Ontario a sufficiently large and representative body of my work to make it worthwhile building a special pavilion or gallery for its permanent display’.101 On 16 December 1968 Norman Reid visited Moore at Perry Green in order to discuss the details of the gift to the Tate. Additional works were proposed, and Moore suggested that displays of the gift should emphasise his processes of working, showing where possible preparatory sketches, maquettes and working models with the final versions of his sculptures.

A deed of agreement regarding the Moore Gift to Tate was signed by Moore, the Tate Director, and the Chair and vice-Chair of the trustees in June 1969. Moore made no specific stipulations with regard to the provision of dedicated gallery space or the number of works to be exhibited at any one time. Instead, the gift was made subject simply to the gallery’s planned expansion, and the proviso that Moore could retain the works during his lifetime, should he so choose, and swap or exchange works on the list of works with the trustees’ approval. These terms were accepted by the trustees in the knowledge that plans for the north-east gallery extension were underway and on the understanding that, given Moore’s close friendship with director Norman Reid and Robert Sainsbury, one of the trustees, there would be no significant changes to the agreed list of works without proper consultation.102

Henry Moore, Barbara Hepworth and Naum Gabo at the Tate Gallery, 10 March 1970

Tate Archive TGA 9313/6/2/181

Fig.47

Henry Moore, Barbara Hepworth and Naum Gabo at the Tate Gallery, 10 March 1970

Tate Archive TGA 9313/6/2/181

Between 1971 and 1974 Moore worked closely with the Canadian curator Alan Wilkinson to draw up a list of possible works for the Henry Moore Centre in Toronto and oversaw the architectural plans for the new exhibition space. During this time the ‘Hoglands Trust’ was also established, initially with a view to the property becoming an outpost of Tate, although it subsequently developed into the independent Henry Moore Foundation. By January 1973, however, the list of works to be included in the gift to the Tate Gallery was still not settled. There was a hope that the maquette studio in its entirety could be secured for the gallery but these discussions never came to fruition.

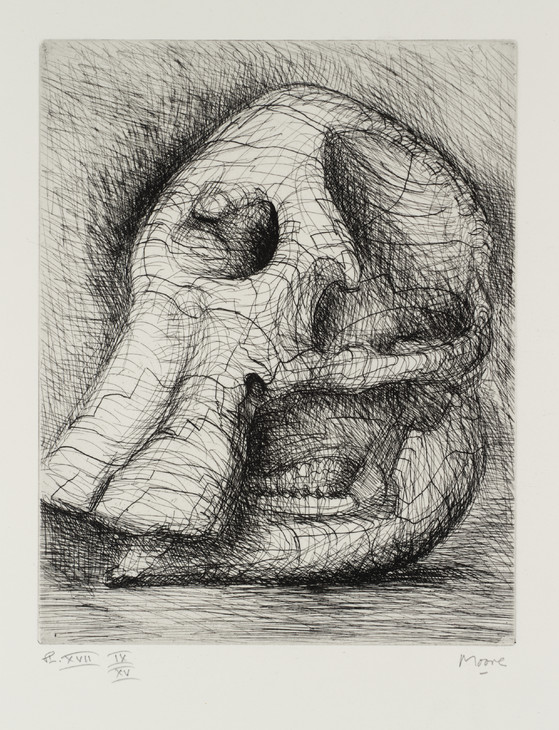

In the late 1960s and early 1970s Moore worked increasingly with etching and lithography. Dedicated studios at Hoglands were set up for his graphic work, and in 1969–70 he created the Elephant Skull Album (fig.48), followed in 1972–3 by the Stonehenge series.

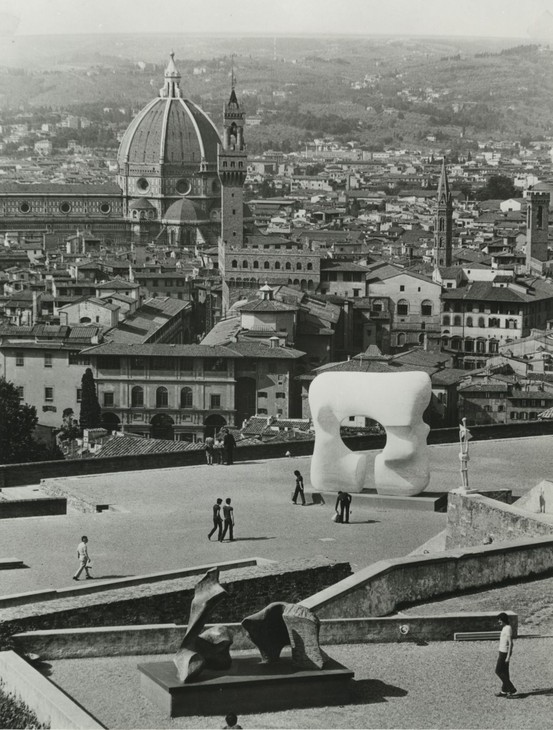

In 1972 the largest and most impressive exhibition of Moore’s work to date was held in the Forte di Belvedere in the outskirts of Florence, attracting 345,000 visitors (fig.49). According to Berthoud, ‘in no other major exhibition of his career was Moore as intimately involved in the arrangements’.104 Many of the works exhibited came from his private collection, or belonged to his wife or daughter; where works were borrowed, Moore wrote letters to private collectors requesting their loan. The exhibition was opened by Princess Margaret. John Thompson, deputy editor of the Sunday Telegraph, pronounced it ‘a stunning climax to the career of the miner’s son from Yorkshire who first found his way to Florence as a student in 1925, and whose imagination has been stirred ever since by the magnificence of the Florentine achievement’.105 However not all of the British reviewers regarded the exhibition in such glowing terms. Guy Brett, writing in the Times, suggested that the simplified forms of works such as Large Square Form with Cut 1969–70 with its vast expanse of smoothed surface dissipated any internal energy or life-force that Moore had conveyed in earlier sculptures.106

Henry Moore OM, CH 1898–1986

Elephant Skull Plate XVII 1969

Intaglio print on paper

image: 253 x 201 mm

Tate P02118

Presented by the artist 1975

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.48

Henry Moore OM, CH

Elephant Skull Plate XVII 1969

Tate P02118

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore Large Square Form with Cut 1969–70 against the skyline of Florence, 1972

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.49

Henry Moore Large Square Form with Cut 1969–70 against the skyline of Florence, 1972

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

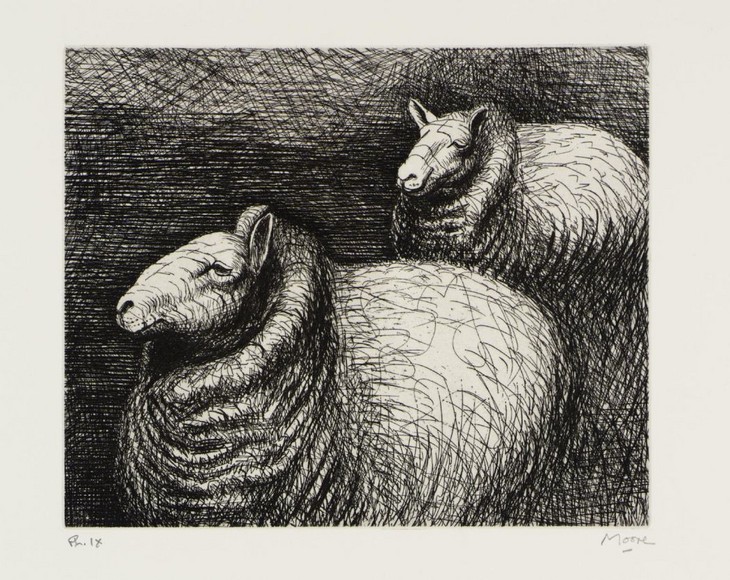

Moore might have been forgiven for slowing down but in the years leading up to his eightieth birthday in 1979 he remained active, overseeing both the enlargements of his carvings at Henraux, and the casting of his bronzes at the Noack foundry. He continued to produce drawings and graphics, creating his Sheep Sketchbook in 1972 and the Sheep Album of intaglio prints in 1974 (fig.50). In 1972 he was invited to create a set of prints interpreting a suite of poems by W.H. Auden. Moore and Auden had been friends since the 1930s and in September 1973 Moore visited him at his home in Vienna to discuss the project. Ten days later Auden died of a heart attack, giving the project a particular poignancy. Moore’s prints were exhibited at the British Museum in spring 1974.

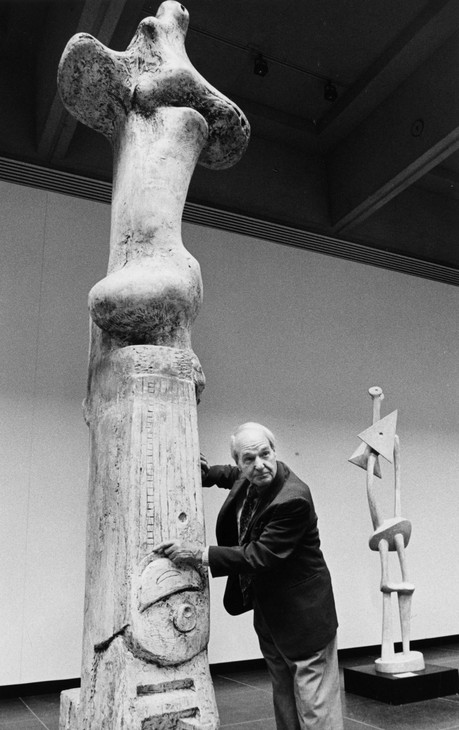

Henry Moore with plaster for Upright Motive No.1: Glenkiln Cross 1955–6. Inauguration of the Henry Moore Sculpture Centre at the Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, 1974

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.51

Henry Moore with plaster for Upright Motive No.1: Glenkiln Cross 1955–6. Inauguration of the Henry Moore Sculpture Centre at the Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, 1974

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

In the summer of 1977 Moore had his first major exhibition in Paris. Although he had exhibited at the Musée Rodin in 1961, his 1977 exhibition at the Orangerie and in Tuileries Garden was on a scale that rivalled the earlier exhibition in Florence. William Packer reviewed the show favourably, writing in the Financial Times: ‘The show is uncrowded, the selection of work extremely well-judged, comprehensive and assimilable, taking us through a life’s work clearly and economically. The surprising result is that prejudice and conditioning are forgotten, and it becomes as though we are seeing the mass of the work, not for the first time, but with fresh eyes.’108

In the same year the details of Moore’s gift were finally hammered out, with an agreement for it to be presented formally to Tate in 1978 during an exhibition of Moore’s drawings planned to celebrate the artist’s eightieth birthday. After some fraught conversations and mixed wires in which Moore suggested reducing the gift from thirty-eight to thirty works, the list recorded in the 1969 deed was agreed. However, when the time came to transport the sculptures in March 1978 in preparation for the exhibition in June, Moore reduced the works to thirty-six, telling Norman Reid that ‘when it came to finalise the list it was discovered that four sculptures ... had already been given by me to my daughter Mary [Danowski], at a date previous to 1969’.109 However, Mary Danowski donated two of the four works so that her father’s gift would present a more comprehensive survey of his work. A press release was duly prepared announcing that ‘The group [of sculptures] is the most substantial gift of works ever given to the Tate by an artist during his lifetime and includes works ranging in date from 1939–40 to 1968’. Two of the works had already been passed to Tate, Locking Piece which had been sited on Millbank since 1968, and Upright Form: Knife Edge, which had been given in memory of Herbert Read.

Woman 1957–8, cast date unknown, installed outside Cartwright Hall, Bradford, during Henry Moore: 80th Birthday Exhibition, April–June 1978

Tate Archive

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Fig.52

Woman 1957–8, cast date unknown, installed outside Cartwright Hall, Bradford, during Henry Moore: 80th Birthday Exhibition, April–June 1978

Tate Archive

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

I.M. Pei and Henry Moore at the inauguration of Dallas Piece 1977–8, City Hall Plaza, Dallas, 1978

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.53

I.M. Pei and Henry Moore at the inauguration of Dallas Piece 1977–8, City Hall Plaza, Dallas, 1978

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Having been diagnosed with a diabetic condition in 1972, and suffering broken ankle in 1974, that Moore was able to do so much travelling in 1978 was remarkable. However, his age was catching up with him, and early in 1980 Moore suffered a mild case of hypothermia. Although he had intended to travel to Madrid for his exhibition there in spring 1981, ill health prevented him. Over the next few years Moore faced the loss of a number of close friends including Sir Philip Hendy, who died in September 1980, Joseph Hirshhorn who died in August 1981 and Sir Kenneth Clark, who died in May 1983.

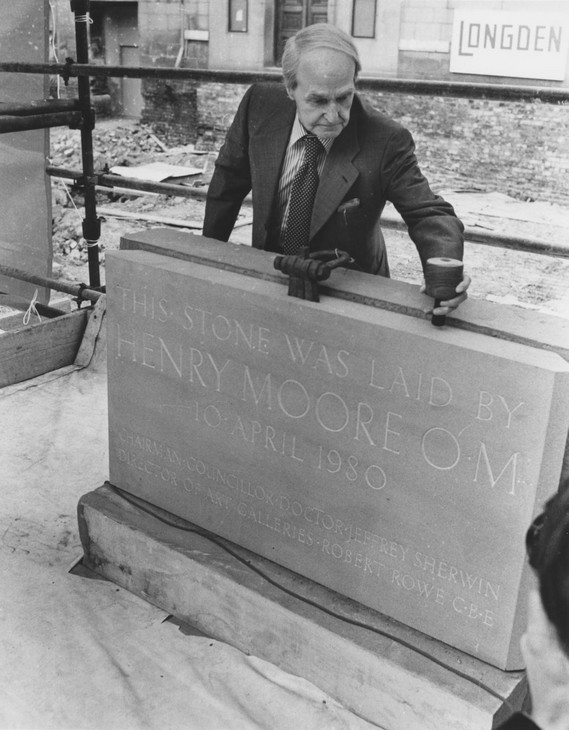

Henry Moore laying the foundation stone outside Leeds City Art Gallery, 10 April 1980

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: The Times, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.54

Henry Moore laying the foundation stone outside Leeds City Art Gallery, 10 April 1980

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: The Times, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Installation view of the exhibition celebrating Moore's eighty-fifth birthday at the Tate Gallery

Tate Archive

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.55

Installation view of the exhibition celebrating Moore's eighty-fifth birthday at the Tate Gallery

Tate Archive

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore with St. Paul's Madonna and Child 1984

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved