Henry Moore: The Plasters

Anita Feldman

Plaster is conventionally seen as merely a means to create a model from which a more durable and more valuable metal cast can be made. As this essay explores, however, it offered Moore new and flexible ways of working that related well to many different aspects of his practice, including his drawings and desire to experiment with scale.

These are not plaster casts; they are plaster originals ... they are the actual works that one has done with one’s own hands.

Henry Moore 19731

Henry Moore 19731

Until recently plasters made by sculptors have been seen as a means to an end rather than as works of art in their own right. Yet these are the very objects that the artist created, textured with a variety of household tools and sometimes hand coloured. They convey an immediacy unlike the bronzes, which are a stage removed. Their inherent fragility can allow more questioning of the vulnerability of the subjects depicted (in Moore’s case, mother and child, reclining figures, fallen warriors). In plaster a sculpture’s surfaces can appear scarred – each incised line clearly marked – unlike the subtle patination of the bronzes with more unified surfaces. This often provides the sculpture with a more intense and disturbing quality, especially those plasters made in the immediate post-war era when artists like Moore were exploring tense and angular forms in his treatment of the figure. Moore himself was acutely aware of the psychological and aesthetic changes occurring in his sculptures once cast from plaster to bronze, and a number were only created in plaster. The vast majority of Moore’s plaster maquettes, where he tested out ideas, were never enlarged or cast in bronze, and despite their inventiveness, the plasters remain unrecorded in the six-volume catalogue raisonné of the artist’s sculpture.2

Henry Moore OM, CH 1898–1986

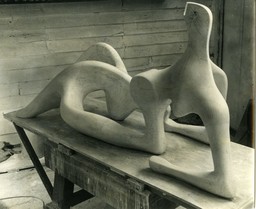

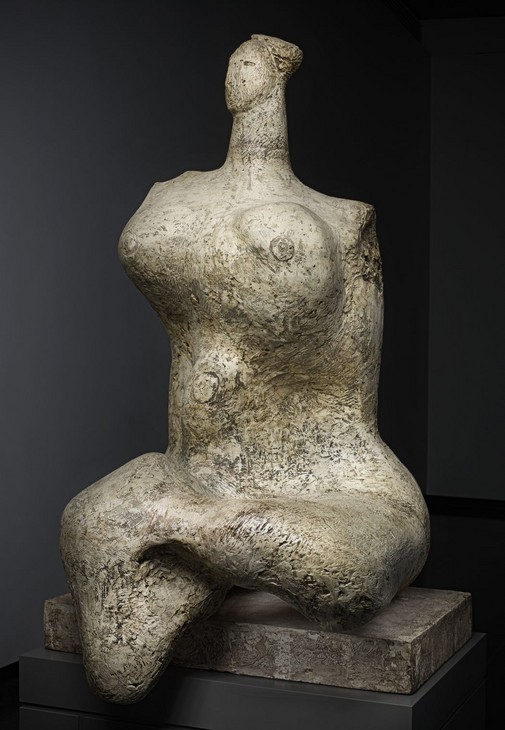

Reclining Figure 1951

Plaster and string

object: 1054 x 2273 x 892 mm, 271 kg

Tate T02270

Presented by the artist 1978

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.1

Henry Moore OM, CH

Reclining Figure 1951

Tate T02270

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Henry Moore

Three-Quarter Figure: Lines 1980

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Photo: Michel Muller, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.2

Henry Moore

Three-Quarter Figure: Lines 1980

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Photo: Michel Muller, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Focusing on the plasters reveals a fuller understanding of Moore’s working methods, in particular his use of this medium to transform found objects such as flint and bone directly into figures, questioning the relationship of man’s existence to the natural world. Occasionally Moore would make pencil drawings on the found object or the plaster in order to realise its transformation. In other maquettes sectional lines, which more frequently appear in Moore’s drawings as a means of delineating form, are attempted in plaster, drawn directly onto the plaster to indicate the ridges that would be incised into a mould for the bronze enlargement. These lines would then follow the undulations of the figure’s form, mapping its contours like an environmental survey. This was most effectively carried out with the plasters for Reclining Figure: Festival 1951 (fig.1) and Three Quarter Figure: Lines, 1980 (fig.2). In these works the string from the original plaster is carried over to create sectional ridges in the bronze.

Henry Moore

The Arch 1969

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.3

Henry Moore

The Arch 1969

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

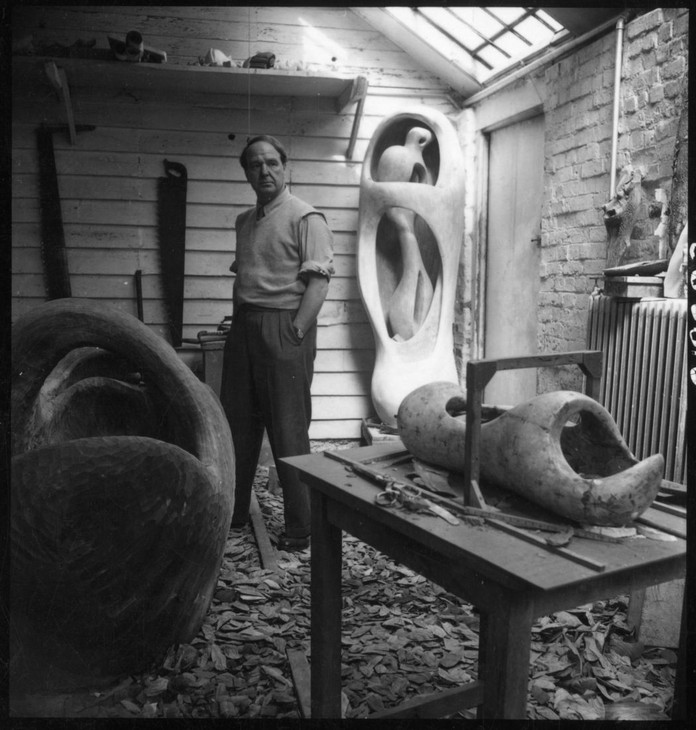

Moore’s temporary Plastic Studio in the grounds of Perry Green allowed him to realise his ideas on a large scale in an area flooded with natural light. His works in plaster could be seen in relation to the lush green surrounding landscape, their white sculptural forms, not yet coloured, dazzling with light, appearing in stark contrast to their setting. Thus in both his use of fibreglass and with the erection of the Plastic Studio, Moore found ways to bypass the intrinsic problem of exposing plaster to the elements. He later recalled: ‘I built this open-air studio of plastic for the Lincoln Centre sculpture intending to remove it afterwards. Now, not only have I come to accept it, but I also find it most useful. It means that I can make large sculptures in natural light and see them from all around at all times.’4

The enlargement of Reclining Figure 1963–5 for New York’s Lincoln Center took Moore’s plasters into a new realm. For this he essentially created a colossal landscape of plaster cliff forms and caves that were reflected in surrounding pools of water outside the studio. In attempting to imagine how the eventual bronze forms would appear sited in a pool at Lincoln Center, Moore created an imagined landscape of monumental forms juxtaposed against the rural Hertfordshire landscape of Perry Green. Unfortunately, the full-scale enlargement of this reclining figure no longer survives, its surreal context made more notable by the contrast of its monumentality with its ephemeral nature.

A more subtle aspect of Moore’s work in plaster is discernible in his architectural reliefs comprising impressions of organic forms first pressed into clay and then united in a bed of plaster. As a rule he refrained from accepting such commissions, feeling that all too often architects considered sculpture as an afterthought, a piece of decoration to an otherwise completed structure. To avoid this subordination, and to work in the complete freedom of his studio without any restrictions as to the eventual siting of a piece, Moore would invite interested architects and potential clients to Perry Green in order to consider already finished three-dimensional sculptural maquettes as ideas that might be suitable for enlargement. Conflict with architectural collaboration is therefore absent from these reliefs, which freely and inventively explore horizontal bands of organic motifs. The plaster maquettes for the Time/Life Screen, 1952–3 were created at a very early stage of planning for Michael Rosenauer’s building on London’s Bond Street, so that the sculptural element was integral to the building itself rather than mere decoration. Moore explained to Rosenauer:

my aim was to give a rhythm to the spacing and sizes of the sculptural motives which should be in harmony with your architecture so that the sculpture could really have some proper relationship to the building, for it seems to me that a portrayal of some pictorial scene in that position would have no connection with your building and would only seem like hanging up a stone picture there, like using the position only as a hoarding for sticking on a stone poster.5

He sought to break free from the limitations of relief carving by creating a screen, pierced to be penetrated by light from both sides, as it would be seen not only from Bond Street but also from an internal terrace. The organic forms of the fourth relief were eventually carved in blocks of Portland stone more than three metres high (fig.4).

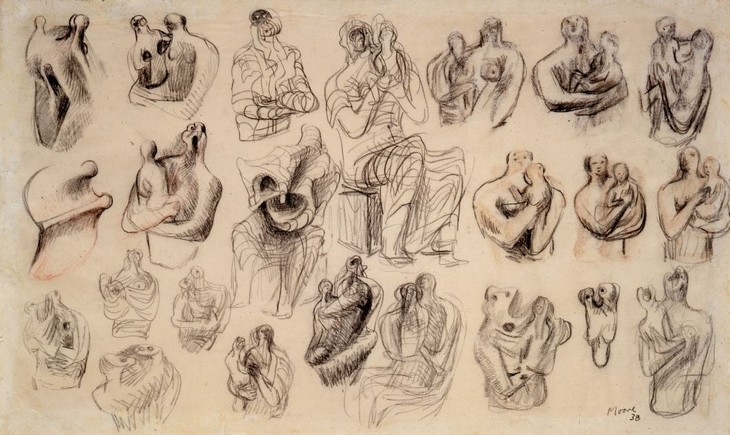

The processes by which Moore transformed natural forms into sculptural elements can be seen in his drawings as early as the 1930s. These compositions reveal the artist’s thought processes, with several drawings on a single sheet, in which found objects are closely scrutinised from every angle and gradually assume human shape. The internal coils of seashells, animal bones and the pointed and hollowed forms of flints from the surrounding sheep fields twist and turn, metamorphosing into standing or reclining figures or mother and child variations. A 1932 drawing of shells, in which the interior shapes of the found objects are articulated as separate anthropomorphic forms, is closely related to plaster reliefs made by Moore the previous year. Such studies in metamorphosis pre-date by four years the seminal International Surrealist Exhibition in London and reveal Moore as a leading figure in the emergence of the surrealist movement in Britain.6

Henry Moore

Studies for Sculpture c.1932

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.5

Henry Moore

Studies for Sculpture c.1932

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Henry Moore

Madonna and Child 1943–4

Hornton Stone

Church of St Matthew, Northampton

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.6

Henry Moore

Madonna and Child 1943–4

Church of St Matthew, Northampton

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Compositions such as Studies for Sculpture c.1939 (fig.5) contain the genesis of many of the sculptural forms developed subsequently, including the 1943 mother and child terracotta studies that led to the renowned Madonna and Child carved the same year for St Matthew’s Church in Northampton (fig.6)7 and Mother and Child 1949. The idea that even realistic representational images ultimately derived from found objects was a radical departure in sculpture. In such compositions Moore questioned the fundamental relationship between man and nature at a time when such an approach was unfashionable. His affinity for natural forms and relentless investigation of the relationship between the human form and its environment was spurned by post-war art critics, and increasingly divided the artist from his contemporaries, though was later recognised by some as one of Moore’s most significant contributions to the sculpture of the twentieth century.8 Yet simultaneously these subjects, concerning the major themes of life, fostered a continuity with the past and confidence in the present, during a period of intense rebuilding of local communities following the devastating aftermath of the war.

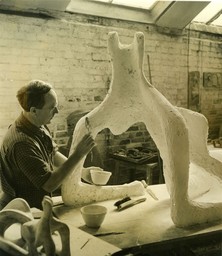

From 1940 Moore maintained a studio solely for the display of found objects and for the creation of maquettes, primarily in plaster. This coincided with his move to Perry Green during the war, when his home and studio in London were damaged during the Blitz; the threat of invasion also led him and his wife to leave their country cottage in Kent. The move to the rural hamlet of Perry Green, within reach of London yet surrounded by open landscape, offered the artist a wealth of inspiration from the natural forms of the gnarled branches and roots of old trees, pieces of flint and remnants of animal bones from surrounding farms. He was free to expand in scale, working on and displaying sculpture in the open fields without the confined limits of an urban studio. Yet, in stark contrast to this expansiveness, his studios at Perry Green were intimate spaces. He tended to have a different studio for each type of activity – the creation of maquettes, the enlargement of his plasters, wood and stone carving, and printmaking. Drawings were often created in the Summer House, a tiny shed barely larger than his chair, attached to a turntable in the Hoglands garden where he could work on paper in the open air. Drawings were sometimes brought into the studios and sculptural ideas created in plaster, in direct response to the sketches.

Photograph showing Upright Internal/External Form 1952–3 in the Top Studio, Perry Green

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Roger Wood, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.7

Photograph showing Upright Internal/External Form 1952–3 in the Top Studio, Perry Green

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Roger Wood, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

A bowl in the Bourne Maquette Studio, Perry Green, containing tiny heads and limbs

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Photo: Michael Phipps, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.8

A bowl in the Bourne Maquette Studio, Perry Green, containing tiny heads and limbs

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Photo: Michael Phipps, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Henry Moore

Maquette for Mother and Child: Hood 1982

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.9

Henry Moore

Maquette for Mother and Child: Hood 1982

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Henry Moore

Mother and Child: Hood 1983

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Photo: Michel Muller, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.10

Henry Moore

Mother and Child: Hood 1983

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Photo: Michel Muller, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

So, why plaster? For an artist as concerned as Moore had been in the interwar years with the mantra of ‘truth to material’, a carver who above all enjoyed the resistance of materials and spent decades hewing forms from blocks of stone and wood, the sudden predilection for plaster and bronze after the war may seem peculiar. But stone and wood have inherent limitations – their material strength determines how far one can continue opening out form – and Moore continually stretched these limits to enable his figures to achieve equilibrium between positive and negative space. The size of the stone or wood blocks was restrictive. Although he did not make sculpture over life size until after the war, he had conceived of monumental sculpture in landscape settings in his drawings as early as the 1930s, and even photographed a number of his works at this time against the sky in order to make them appear colossal. Plaster enabled Moore to experiment freely with both form and scale, and also to work directly with found objects and incorporate them physically into his work at the maquette stage. Finally, plaster had the distinct advantage of being able to be both modelled and carved. Once set, it could be chiselled and chipped away just like stone or wood.

Moore’s sculptures were for the most part created as a step towards the creation of a bronze, and many were destroyed or decayed as a result of their fragility. While many were divided into several sections and damaged beyond repair by the foundries during the course of bronze casting, the artist deliberately destroyed others, as one might score an etching plate, in order to avoid future casts being taken beyond the authorised edition. These plasters have been historically undervalued by both artist and art historian alike, yet they are the originals, shaped and textured with assorted chisels, metal files, dental instruments, cheese graters, even humble nutmeg grinders and toothbrushes; each bronze is intrinsically a step removed from the original creation. Moreover, Moore’s plasters are frequently delicately coloured with walnut resin to give them warmth or with a pale green wash to emulate the bronze dust that often accumulated on them over time in the foundries. This green dust settled in the crevices of the plasters, as an edition could often take one or more years to complete, each bronze being cast only when a buyer was found. Although plaster casts would be made for various stages of the enlargement process, a plaster original is unlike any other work and is unique. Moore recounted:

A friend who works at the Victoria and Albert Museum came out one day just as we were breaking up some plasters and said, ‘But why do that, because sometimes the original plaster is actually nicer to look at than the final bronze’. He was right because sometimes an idea you’ve had and that you’ve made in the original material or plaster can suit it better than what the final bronze may do. Especially to begin with it was difficult for me to visualise for sure just what the plaster I was doing would look like in bronze.9

This led to Moore’s decision not to continue destroying his plasters, leaving him with the conundrum of having too many of them to store. He did not want to sell them, in order to protect limited editions of his work from the possibility of unauthorised casts being produced and entering the market. Some important plasters found homes in UK institutions such as Tate (Reclining Figure: Festival 1951 and Seated Woman 1957, figs.1, 11); others were lent as legacies to institutions abroad after significant public works had been sited nearby. Hence the plaster Reclining Mother and Child 1975–6 can be found in the Dallas Museum of Art following installation of the major bronze Three Forms Vertebrae 1979 outside I.M. Pei’s Dallas City Hall.

The vast majority of Moore’s monumental plasters, however, ended up at the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto. In 1967 Moore visited Toronto to see The Archer 1964–5, which had recently been sited in Nathan Phillips Square. The commission of this sculpture was so fiercely contested that it cost the mayor his re-election; the uncompromising dedication of the citizens of the city as they raised the funds entirely from public donations made a deep impression on Moore. At the same time he had been negotiating a major gift to the Tate Gallery, only to read a letter in the Times, signed by many younger British artists, notably including his former assistants Phillip King and Anthony Caro, who claimed to be concerned that the gallery would be giving over too much space to a single artist. The Tate Gallery prevaricated. The debacle ended in 1973 with Moore making a gift of some fifty-seven plasters and bronzes to Toronto instead, where they remain in a dedicated gallery, in which Moore himself had some influence in the design.10 When he saw that the plans featured clerestory lighting along the edges of the walls, he wrote to the architects suggesting that the entire gallery be flooded with natural light from above, leaving the walls themselves slightly darker so that the plasters could be seen with dramatic effect.11 These were arranged by the artist in a crowded open space like colossal remnants of archaeological ruins, with the visitor wandering among textured forms akin to the chalky cliff faces of Dover and the powerful, time-resilient blocks of Stonehenge. The gift to Toronto at once ensured two things for Moore: that the bulk of his plaster originals would be held in a major art institution and thus protected from entering into free circulation whilst still in the public domain, and that they would be appreciated as works of art in their own right. Alan Wilkinson, who was appointed the first Curator of the Moore Center in Toronto, recalled how the artist’s assistants John Farnham, Michel Muller and Malcolm Woodward carefully removed the dark shellac which had been applied to the plasters during the casting process, ‘to reveal more clearly the extraordinary variety of surface details and textures, each of the original plasters having its own unique surface colouring and tonality’.12

Restoration of the original plasters continues at the Henry Moore Foundation at Perry Green, one notable example being the restringing of the 1930s plasters carried out by James Copper in 1998. The stringed sculptures were experiments in investigating interior forms that Moore made over just three years from 1937 to 1939. The original string would have been destroyed during the casting process, although some original unused remnants survive. These strands, some of the artist’s original records and the bronze casts enabled identification of the original colours for restringing of the plasters. The strings make it possible to view one form through another, an effect heightened in some cases with more than one colour of string. Moore spoke of the stringed mathematical models he studied in the Science Museum in London, but he was also doubtlessly influenced by Naum Gabo, whose constructivist work in strings he would have known initially from journals and then from their relationship as friends and neighbours in Hampstead, where Gabo settled (among many other political refugees) as fascism engulfed the continent. But Moore seems to have tired of stringed works after a few years, in the end preferring to work with more organic and human forms.

However, the concept of internal/external forms, which had been first explored in the stringed sculptures, was one that Moore returned to throughout his career. In his series of helmet works, the external form becomes a protective shell, a barrier against the outside world, protecting the inner forms. Moore’s inventive use of plaster have is evident with his re-use of an outer shell section from Maquette for Helmet Head No.6 1975, cast in plaster and turned on its side to become the great arching drapery of Maquette for Three Piece Reclining Figure Draped 1975.

Henry Moore

Woman 1957

Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Fig.12

Henry Moore

Woman 1957

Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Full-size plaster of King and Queen 1952–3 in Moore's studio with an alternative queen's head

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Fig.13

Full-size plaster of King and Queen 1952–3 in Moore's studio with an alternative queen's head

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

But it was in the 1950s that Moore really got his teeth into plaster, exploiting the medium’s ability to create twisting, angular and distorted figures that capture the alienation and anxiety of the post-war era. Often the plasters are far more disturbing than the bronzes cast from them. In Woman 1957 (fig.12) the dismembered torso harkens back to prehistoric fertility figures while at the same time evincing a distinctly modern pain. Even with the elegiac King and Queen 1952–3 (fig.13) there is something disconcerting about the cross-hatching and apparently scarred features, which in plaster are heightened to an intensity that is not present in the bronze. Sculptor Anthony Caro worked with Moore during the early 1950s and recalls initial trials in wax:

when I was with him he started working in wax for casting into bronze. He would pour the hot wax on to a flat plaster bat, and when it was dry, cut out shapes like a tailor. Then he would bend the bodies and affix the heads which he had previously dipped into hot water. This, sitting at the table in the studio alongside Alan Ingham and myself, was how he fashioned the ladder-back figures, the maquettes for King and Queen and the warrior pieces.13

Several abstract trials in plaster for the heads of King and Queen reveal that they were originally conceived as much more anxious and tense than the final version. This is made all the more disturbing by the jarring contrast to their otherwise calm and more naturalistic poses. Moore’s circumstances during the two World Wars is well documented. He faced heavy combat in the Battle for Bourlon Wood in November 1917, at just nineteen years of age, only to fall victim to a gas attack at the Battle of Cambrai; he was one of only fifty-two survivors from a battalion of 400. Moore rarely spoke of these events; but an internalised anxiety can perhaps be detected in his sculpture years later. Figures like Seated Torso 1954 (fig.14) are reduced to an almost skeletal core, headless, yet the figure sits with a real three-dimensional presence: it is alert, and in the room with the viewer, though the plaster is textured to create a raw, ‘unfinished’ surface.

Other sculptures, such as Reclining Figure No.4 1954, embody a classicism evocative of Greek antiquity, with their use of drapery and poses familiar from the classical canon. Often the paleness of the plaster is contrasted with a richly-textured grey-brown surface colour. This effect strongly echoes Moore’s Shelter Drawings, where white wax crayon resists the coloured washes to create figures that emerge, ghost-like, from the darkness; forms are further heightened and delineated with pen and ink and gouache. In fact, the pose of Reclining Figure No.4, with its head raised as it gazes outward and its upraised knees, relates to Moore’s studies of figures in the Underground. His photographs of Pompeii, taken in October 1954, show similarly diminished, tense, hollowed reclining figures, entombed in white ash not unlike his plasters. The nervous tension of his plasters of this period also evokes something of the Swiss sculptor Alberto Giacometti, of whom Moore revealingly said: ‘In Giacometti’s work the armature has once again become the new life-line of the sculpture’.14 It is this same armature of human vulnerability and resilience that pervades Moore’s work in sculptures such as Warrior with Shield 1953–4.

Henry Moore

Working Model for Draped Seated Woman: Figure on Steps 1956

Painted plaster, paper and hessian on metal support

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Michael Phipps, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.15

Henry Moore

Working Model for Draped Seated Woman: Figure on Steps 1956

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Michael Phipps, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

These plasters marked the beginning of a new era for Moore as a sculptor concerned with the role of modern art – and of the artist – in a post-war world. He addressed Unesco’s International Conference of Artists in Venice 1952 with a paper entitled ‘The Sculptor in Modern Society’:

sculpture even more than painting (which generally speaking is restricted to interiors), is a public art, and for that reason I am at once involved in those problems which we have met here to discuss – the relationship of artist to society – more particularly, the relation of the artist to the particular form of society which we have at this moment in history ... we have a society which is fragmented, authority which resides in no central place, and our function as artists is what we make it by our individual efforts.16

Working in plaster and bronze meant that he could not only expand his formal exploration of sculpture – he also had a freedom of scale not hitherto available. He could communicate the universal forms of man and nature while at the same time allude to mankind’s stoicism with a distinctively modern treatment of sculpture. In his Reclining Figure: Festival fig.1 he felt that he had achieved for the first time complete balance between positive and negative space, opening up the figure to a point inconceivable in stone or wood, and where form and space are equally significant, symbolic of a new confidence in post-war Britain with its ‘paradoxical dynamic thrust and tense and majestic repose’.17

Henry Moore

Plaster mould for Standing Figure 1950

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.16

Henry Moore

Plaster mould for Standing Figure 1950

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

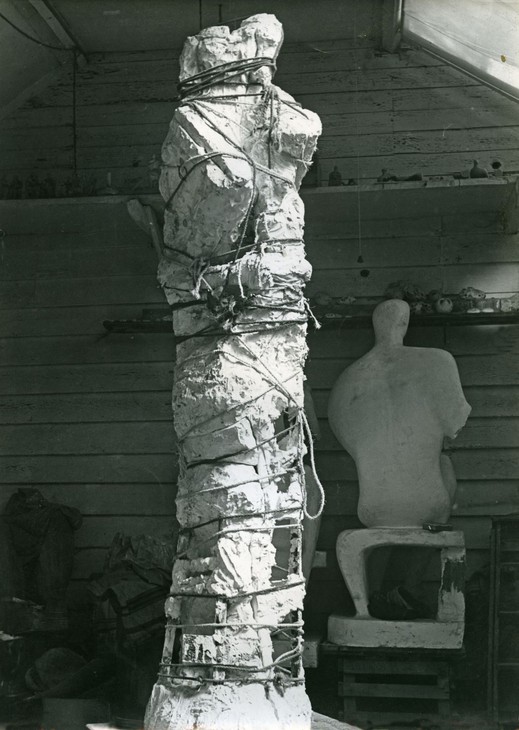

Henry Moore

Wrapped Madonna and Child: Day Time c.1951

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.17

Henry Moore

Wrapped Madonna and Child: Day Time c.1951

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

While predominately working out ideas for sculpture with plaster maquettes and found objects, Moore’s drawings became increasingly inventive and related to the plaster sculptures in unique ways. The plaster in progress for Standing Figure 1950, its armature tied with rope and heightened dramatically in the top-lit studio, became the intriguing subject of eight drawings in which the subject was transformed into a Wrapped Madonna and Child (figs.16 and 17). Such a transformation also occurred the other way around, with a found object drawn and then a plaster made based on the drawing.

Henry Moore

Two Piece Reclining Figure: Armless 1975

Plaster with surface colour

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.18

Henry Moore

Two Piece Reclining Figure: Armless 1975

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Henry Moore Foundation Archive

From the late 1960s Moore began using polystyrene to enlarge his plasters from the working model stage to full size. He attributed his first use of polystyrene to the theatrical sets he designed for the staging of Gian Carlo-Menotti’s production of Mozart’s Don Giovanni in Spoleto in 1967. Polystyrene was easily scaled up, lightweight and portable. Plaster sculptures would be cut into sections, each section corresponding to a section of polystyrene. Polystyrene as a medium for shaping was not very sympathetic to carve, so he often made a plaster cast of the polystyrene enlargement so that he could work with plaster in order to achieve the desired texture and finish before casting in bronze. This can be seen in the plaster and polystyrene series of working models which led to Mirror Knife Edge 1977 at the entrance to the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C – the two monumental, hard-edged forms being an inversion of Knife Edge Two Piece 1962–5, famously sited outside the Houses of Parliament in London. Moore also had a cast of the latter positioned within view of his home at Perry Green.

Henry Moore

Seated Woman 1986

Plaster

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Jonty Wilde, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.19

Henry Moore

Seated Woman 1986

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All Rights Reserved

Photo: Jonty Wilde, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Henry Moore

Working Model for Seated Woman 1980

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Photo: Dennis Gilbert, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

Fig.20

Henry Moore

Working Model for Seated Woman 1980

© The Henry Moore Foundation. All rights reserved

Photo: Dennis Gilbert, Henry Moore Foundation Archive

The large plaster Seated Woman 1986 (fig.19), cast in plaster from painted polystyrene, was still being worked on at the time of Moore’s death in 1986, although it had begun thirty years earlier as part of a family group maquette that was never cast. Abandoned in his studio, the full-scale work remains unfinished, its smooth, pale form in stark contrast to the roughly gouged trial marks on the knee. Yet it is possible to imagine what the finished sculpture would have looked like from looking at the working model its fine green wash subtly picking out the contrasts of smooth surfaces with robust textured areas (fig.20). Admiring a small Egyptian plaster head, Moore once said, ‘Well, if that plaster has lasted for three thousand years, so should my plasters’.18 Questions persist concerning the care and restoration of these original works, as does discussion of their value in real, historic and aesthetic terms, but contrary to conventional views on this matter, it is clear that the significance of plaster as a sculptural medium for Moore was profound.

Notes

Henry J. Seldis, Henry Moore in America, London and New York 1973, pp.222–4, cited in Alan Wilkinson (ed.), Henry Moore: Writings and Conversations, Aldershot 2002, p.76.

See Alan Bowness (ed.), Henry Moore. Volume 3: Complete Sculpture 1955–64, London 1986, pp.50–1, for some plaster variations that were destroyed and never cast. Roughly ninety per cent of Moore’s plasters maquettes were not developed into larger works.

Moore lived in the rural Hertfordshire hamlet of Perry Green for over forty years. Since 1977 it has been the location of the headquarters of the Henry Moore Foundation and the artist’s home, studios, gallery and sculpture grounds are open to the public.

Henry Moore interviewed by John Hedgecoe in 1968 (John Hedgecoe (ed.), Henry Moore, London 1968, p.70).

Henry Moore, letter to Michael Rosenauer, 10 March 1952, Michael Rosenauer Archive, Nordico-Museum der Stadt, Linz.

Moore served on the Organising Committee and exhibited work in the International Surrealist Exhibition at the New Burlington Galleries, London, in 1936.

The central maquette, which also appears in the centre of the drawing, was carved in Hornton stone for the Church of St Mary’s in Barham in 1948–9.

See Clement Greenberg, Collected Essays and Criticism, vol.2: ‘Arrogant Purpose’ 1945–9, Chicago 1986, pp.126–7.

Today the Art Gallery of Ontario collection comprises nearly nine hundred sculptures, drawings and graphics by Moore, and is second only to that of the Henry Moore Foundation. Moore made a major gift of sculpture, drawings and graphics to Tate in 1978.

Alan Wilkinson, Henry Moore Remembered: The Collection at the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto, Toronto 1987, p.17.

Anthony Caro in Chris Stephens (ed.), Henry Moore, exhibition catalogue, Tate Britain, London 2010, p.39.

Acknowledgements

This essay was first published in Henry Moore: Plasters, London 2011. We are grateful to the Royal Academy for its permission to republish it in edited form.

Anita Feldman is Deputy Director for Curatorial Affairs at the San Diego Museum of Art.

How to cite

Anita Feldman, ‘Henry Moore: The Plasters’, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015, https://www