Editor's Note

As an official war artist during the First World War, William Orpen may have been expected to depict the gallantry and glory of soldiers, as artists before him had done, but, as subsequent testaments, memoirs, poetry and paintings by witnesses attest, the unparalleled carnage would leave artists grasping for a new language.

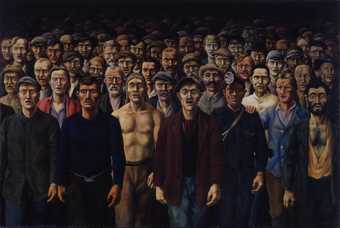

As Joanna Bourke writes, Orpen wanted to expose viewers of his work to the vile realities of war, to see not only the 'amputated hand lying on the duckboards' but also the psychological aftermath of conflict. A dazed and partially clothed soldier, the survivor of a bomb blast, became the subject of Orpen's painting Blown Up 1917, in what was the first depiction of shell shock by an artist.

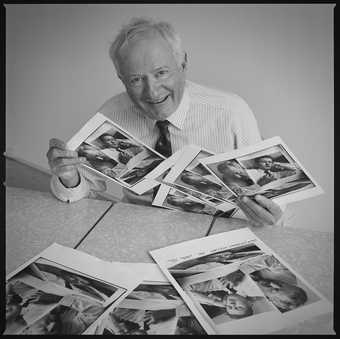

One hundred years on, the fallout of war on combatants and their families is an ongoing issue. A sizeable number of veterans are traumatised, homeless or unable to integrate back into normal life. So, when we remember the fallen of 1914 to 1918, let us not forget those who are suffering now, wherever they may have served. Nor should we forget the contribution of African soldiers during the Great War. William Kentridge's new piece – made in collaboration with composer Philip Miller, musical director Thuthuka Sibisi and choreographer Gregory Maqoma – premieres at Tate Modern this summer, focusing on the little-known story of the hundreds of thousands of African soldiers and civilians who served. Kentridge and his collaborators call this multi-faceted, multi-layered production (titled The Head and the Load) an 'interrupted musical procession', which at its heart explores, in Kentridge's words, the 'incomprehension: of Africa by Europe, of Europe by Africa'.

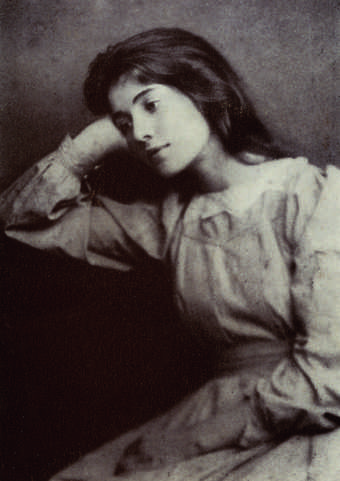

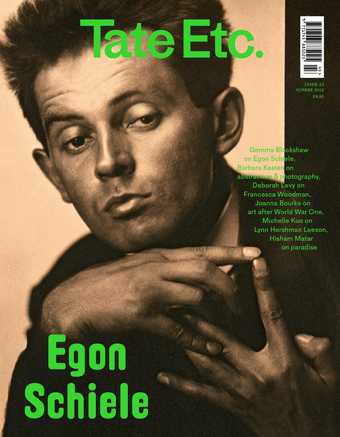

The year 1918 was also the year that saw the death of at least 50 million from a global influenza pandemic. One victim was the Austrian artist Egon Schiele, who died aged only 28, just two months after his pregnant wife Edith. While we could regard his self-portraits as neat visual parallels to the horror of war, they were, as Gemma Blackshaw writes, studiously borrowed from the 'pathological expressions' found among patients at Steinhof, Vienna's leading psychiatric institution.

Schiele understood the power of the artist as persona. However self-absorbed his cri de coeur might appear now, his extraordinary works no doubt still resonate with those stricken soldiers who have dared to stare death in the face, for our sake.