Donald Rodney in his studio at the Slade School of Art, 1987

Courtesy Diane Symons

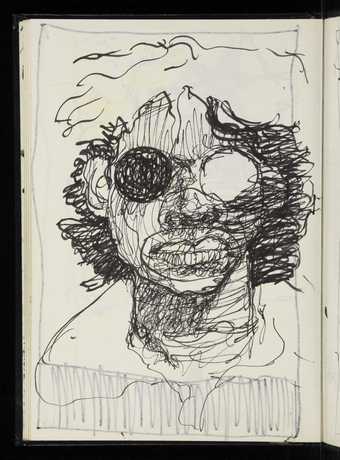

The ships never ceased coming. They come through oblivion, the Atlantic’s death clinic, to his Homerton Hospital bed. He sees them, in stark revulsion, contemporaneous with the pain that will become his own death. They haunt him to bear the brutal burden of witness.

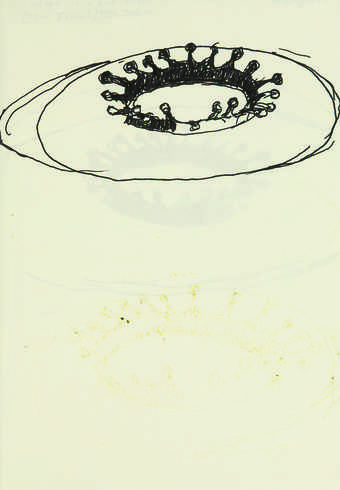

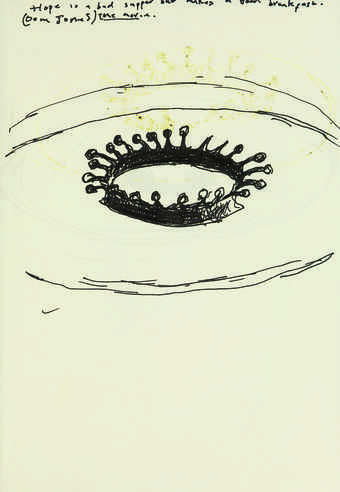

When he sees the ships this time, he draws in his sketchbook two drips of blood suspended in the air. Where they fall a concentric abyss rings out. In the middle echoes a coronet, the splash crown. There the ships plunge, soundlessly disappearing – condensed, but not gone, into a circular delirium that is no less the terror, as Borges once put it, ‘that someone else was dreaming him.’ The someone else, in this instance, is the artist himself, Donald Rodney (1968–1998).

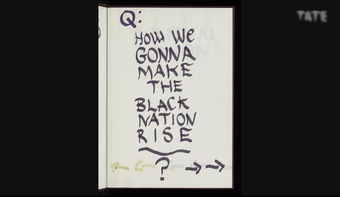

Prior to, or after, one of his numerous surgeries, Rodney writes:

I was in hospital again and during the injection of Maximum dose pethidine to kill the pain I drifted off to a landscape Nightmare. I flo[a]ted above everything [on] a sea of glass on which sailed a boat filled with slaves but somehow we were connected by blood and bone and flesh and storms raged.

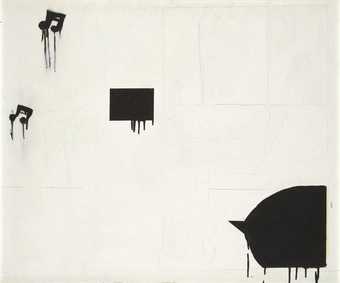

Rodney’s art enacts a powerful form of inner witnessing to the original crime of transatlantic slavery. The splash crown, drawn with sensuous and volatile lines over many pages, alters slightly, circles what his ancestors endured. Through it he grasps a finite view of their infinite pain.

Page from Donald Rodney's sketchbook number 41, 1995

© Estate of Donald Rodney

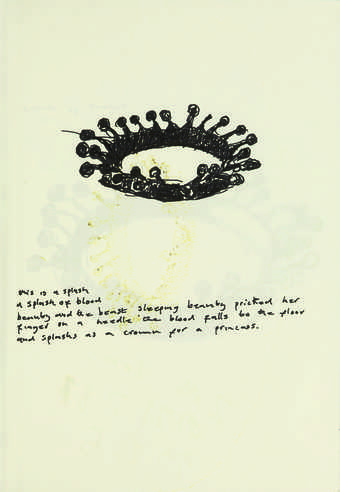

Page from Donald Rodney's sketchbook number 41, 1995

© Estate of Donald Rodney

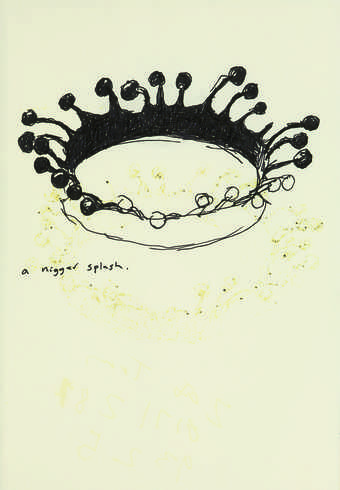

Page from Donald Rodney's sketchbook number 41, 1995

© Estate of Donald Rodney

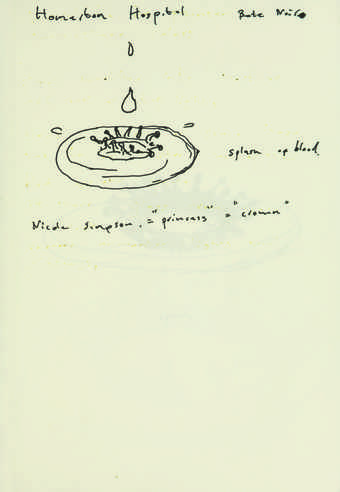

Much of Rodney’s brief life was spent in hospitals. A hospital, for him, was a veritable slave ship, looming from the past to the present, intensifying his physical and psychological torment each time he underwent surgery. He died in one in 1998, at age 36. The cause of death was sickle-cell anaemia, what he called his ‘BLK BLOOD DISEASE’. Why, at this particular moment of agony – an operation – the vision of the slave ship, that particular oceanic pain, blurs? Inexorably, blood.

Rodney’s nightmare is a mirror. The phantasmagoria of history is there as an active presence, bound to the future by blood. In his words, ‘somehow we were connected by blood …’, the ‘somehow’ has a sincere, healing tone. This sincerity, however, is not due to nostalgia or any other narcissistic impulse; the force of the recognition of his connection is an infraction of both time and consciousness. Yet, ‘somehow’ – somehow – redeems the tragic fate of the descendants of slaves, those who are doomed to live as victims and posthumous witnesses to slavery’s prevailing injustices. The blood recognition converts doom to defiance. It conducts the wrestle with history outside of the metaphysical prison of history and within oneself, where the struggle is most radical and most transformative. Such autonomy, the autonomy of one’s body, is a politics that refuses vengeance or atavistic revenge. It is a politics that rejects purification, and embraces, while it also confronts, being contaminated and the right to vigilant, explicit protest. It aims to amplify what approves life and is life’s sole authority: one’s blood, which cannot be refuted, neither by death or any other oblivion.

The result is an art of strange grace. And Rodney’s splash crown series creates, in situ, a special, fluid vernacular of resistance. Resistance begins with blood.

Page from Donald Rodney's sketchbook number 41, 1995

© Estate of Donald Rodney

Page from Donald Rodney's sketchbook number 41, 1995

© Estate of Donald Rodney

Page from Donald Rodney's sketchbook number 41, 1995

© Estate of Donald Rodney

All of his work meditates on that authority of blood. Each functions as a personal documentary that questions the imperial pathology, inherited – like the doctrine of original sin itself – at birth, even before he was born. The documentary moves within the scope of fable, however, and does not depend on an aesthetic of pathology. It strikes an imaginative resonance, transfiguring the appalling postcolonial body politics as he experienced it in his lifetime in England. Those were the Margaret Thatcher and the Enoch Powell years. The Thames, not the Tiber, was foaming with much blood.

But England was, and is always, royal England. There ‘no bloodless myth will hold’, in the voice of one of her poets, though the sovereign crown represents – through inaction and silence – slavery as a fallacy of mythology. Rodney’s splash crown, in turn, signifies and reminds us that slavery is monarchical, far from mythological. Atrocity flows directly from the divine head. In plain ink, his splash crown revolts against his sovereign’s violence of abstraction. By rendering visible the dark innocence pervading the crown – at times with texts, like this one – the violence becomes at once surreal and concrete:

this is a splash

a splash of blood

beauty and the beast sleeping beauty pricked her

finger on a needle the blood falls to the floor

and splashes as a crown for a princess

The fable’s gravitational cadence emphasises imperial menace. Bloodlust. Other texts by Rodney convey savage mockery and indignation: ‘a crown of thorns’; ‘a nigger splash’. Their effect – and the splash crown’s total visual effect – further crack the mirror of colonial disillusionment to insist on healing. Healing: that is the lasting dignity of Rodney’s splash crown, created from his hospital bed and venerating the real provenance of blood – that which survives the aftermath of surgery and slavery, and that grows, irrepressibly, without end, across the black Atlantic.

Page from Donald Rodney's sketchbook number 41, 1995

© Estate of Donald Rodney

Donald Rodney’s sketchbooks are available to view by appointment in the Tate Archive.

Ishion Hutchinson is a poet and writer. He teaches in the graduate writing programme at Cornell University and is a contributing editor to the literary journals The Common and Tongue: A Journal of Writing & Art. His second collection of poetry House of Lords and Commons is published by Faber & Faber.