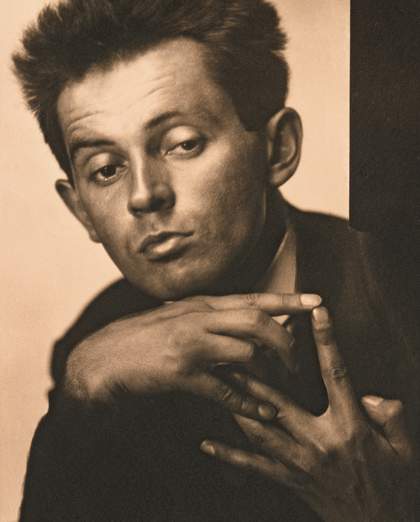

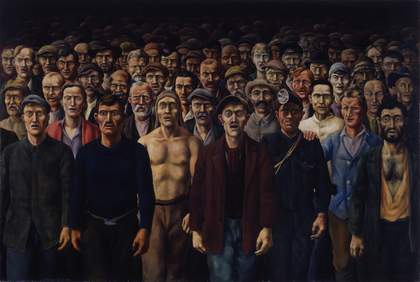

Otto Griebel, The International 1928–30, oil paint on canvas, 125 x 185 cm

Stiftung Deutsches Historisches Museum, Berlin / A. Psille. © Estate of Otto Griebel

War hurts. Perpetrating, experiencing and witnessing acts of incredible cruelty harms everyone. It ‘corrupts the chambers of the heart’, as war poet and former soldier RL Barth put it. Trauma is the suffering of survival.

Representing the pain of war was a formidable task facing artists during and immediately after the 1914–18 conflict. Was it even possible to capture the horrors of industrial warfare in pencil or paint, crayons or celluloid? Nearly everyone recognised that the heroic battle panoramas produced by traditional war artists such as Nicolas-Toussaint Charlet, Jacques-Louis David, Antoine-Jean Gros and Elizabeth Butler (Lady Butler) were unseemly. Modern warfare seemed much more impersonal and chaotic than its predecessors. Questions were raised about the aesthetics of atrocity. Was there a danger that visually representing an obscene, violent act would reproduce its violent obscenity? Might viewers become accustomed to barbarian ways or, worse, end up celebrating death and openly fetishising courage, gallantry and honour? There was also a risk of repeating the great lie of war: that suffering is redemptive.

Félix Vallotton, Military Cemetery at Châlons-sur-Marne 1917, oil paint on canvas, 54 x 84 cm

Collections La contemporaine

William Orpen struggled with such questions. As an official war artist, he was profoundly conscious of the need to expose people back home to the realities of the modern battlefield. He wanted people to see the amputated hand ‘lying on the duckboards; a Boche and a Highlander locked in a deadly embrace … the “Cough-drop” with the stench coming from its watery bottom; the shell-holes with the shapes of bodies faintly showing through the putrid water.’ Trauma was his constant theme. In Dead Germans in a Trench 1918, he contrasted the green of putrefying flesh with a wattle-revetted trench against the dazzling white of the chalk spoil and a sunbright sky. Women, too, were war’s victims, as represented by the traumatised Mad Woman of Douai 1918, catatonic after being raped by German soldiers and sitting in a destroyed town next to a shallow grave.

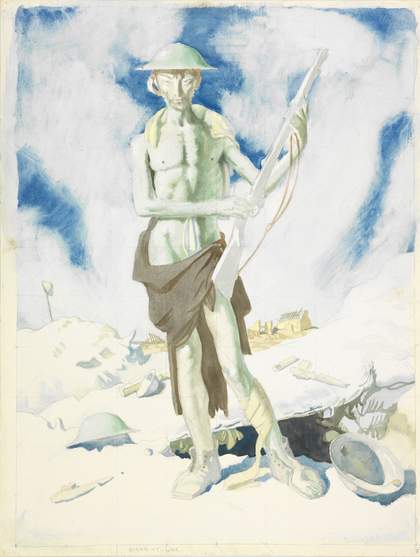

Orpen’s most direct reference to the traumas of war, however, can be seen in Blown Up 1917. It was based on a soldier he had seen wandering a corpse-strewn landscape in France. ‘Practically every shred of uniform had been torn from his body’ by the explosion of a mine, Orpen later recalled. The shell-shocked soldier ‘was wandering crazed and naked, still clinging to his rifle’.

William Orpen, Blown Up 1917, graphite and watercolour on paper, 58.4 x 43.1 cm

© Imperial War Museum

Long after the guns had been silenced, this emaciated, semi-naked figure haunted Orpen’s imagination. He had been commissioned to paint a majestic portrait of the eminent politicians, generals and admirals ‘who had won the war’, grouped in the Hall of Peace at the Palace of Versailles. He could not stomach the lie. After spending nine months working on the composition, Orpen suddenly found that he ‘couldn’t go on. It seemed so unimportant somehow beside the reality as I had seen it ... I kept thinking of all these men who will remain in France forever.’ Orpen was appalled that the men who had ‘given up their all’ and ‘gone through Hell, misery and terror of a sudden death’ were ‘being forgotten ... One was almost forced to think that the “frocks” won the war.’ In an act of defiance, he ‘rubbed all the statesmen and commanders out’. In their place, he placed a coffin of an unknown soldier draped in the Union Jack. As emblems of love, two putti floated above the coffin and the Unknown Soldier was watched over by two semi-naked Tommies wearing tin hats, holding rifles, and with broken soles and unwound puttee. These two shell-shocked soldiers were portraits of the madman he had encountered in No Man’s Land. For Orpen, Blown Up and To the Unknown British Soldier in France 1921–8 were attempts to remind people of war’s trauma.

William Orpen, Original verison of To the Unknown British Soldier in France 1921–8, first exhibited at the Royal Academy of Arts in 1923

© Imperial War Museum

During the war, and for the rest of his life, Orpen railed against civilians who doggedly refused to acknowledge the suffering of men in the frontlines. Instead, they nattered on about being overworked while ‘millions of men were running a big risk of being blown to eternity at any moment, day or night’. Wasn’t that madness? The war poet Herbert Read believed so. Like Orpen, he observed that: ‘it must have been the experience of many men, when the war was over and they came back with minds seared with the things they had seen, to find a civilian public weary and indifferent, and positively unwilling to listen.’

In fact, he lamented, civilians were ‘suffering from a war-neurosis far worse than any the active soldier had contracted’. Grafton Elliott Smith and Tom Hatherley Pear, the authors of a 1917 book entitled Shell Shock and Its Lessons, went even further. They noted that it was common to describe shell-shocked men as losing their reason while, in fact, the opposite was the case: the sensibilities of those broken men returning from the front lines were ‘not lost, but functioning with painful efficiency’. It was insane not to be driven mad by the sights, smells, and sounds of war between 1914 and 1918.

The problem for everyone was how to make sense of such war-induced trauma. Why should so many healthy young men suffer profound emotional collapse as a result of their war service? In 1914, the concept of ‘trauma’ was actually a fairly recent one. Even though it had been described in the 1860s by physician John Eric Erichsen, who had observed the emotionally disruptive effects arising from railway accidents, it took until the 1914–18 war for the concept to enter into public parlance. Even then, it was only vaguely understood. The term ‘shell shock’ had been coined in 1915 by physician Charles Meyers, who initially believed that the affliction was the result of a shell exploding nearby, causing shockwaves that literally severed men’s nerves. It took time for ‘shell shock’ to be recognised as a psychological and emotional disorder, rather than a physiological one.

André Mare, Survivors 1929, oil paint on canvas, 40 x 32 cm

Collections La contemporaine

Even then, hierarchies of suffering were generated. In the highly stratified British class system, the emotional suffering of lowly privates could be denigrated as hysterical, womanish, even a form of ‘skrimshanking’ (or shirking). In contrast, the suffering of men in the officer class was more likely to be classified as an anxiety disorder, which was believed to have arisen after a period of maintaining that much valorised British stiff upper lip. Such diagnoses mattered. It determined whether sufferers were paid a pension or slapped; reassured or rebuked; treated with hypnosis or electric shocks; asked to lie down on the psychoanalytic couch or shot at dawn.

It was not only combatants who had to shoulder their share of war’s trauma, though. Artists, too, became progressively bitter as they witnessed young men who naively believed in ‘Honour, Glory, and England’ being sent into stupid battles planned by incompetent generals. The bloodbath at Passchendaele was decisive for young artists such as Paul Nash. In an angry letter to his wife Margaret, he explained that the war was ‘unspeakable, godless, hopeless’. Its horrors were so great that he no longer considered himself to be ‘an artist interested and curious’, but was instead a ‘messenger who will bring back word from the men who are fighting to those who want the war to go on for ever’. Although his message might be ‘feeble, inarticulate’, he promised that it would have a ‘bitter truth, and may it burn their lousy souls’. One result was his watercolour Wire 1918–19.

This was not the message that governments hoped artists would spread. Artists who had been appointed to offer visual slogans conducive to raising morale found themselves under attack when they failed to produce the requisite propaganda-friendly images. When German artist Otto Dix exhibited the searing indictment on war in The Trench 1923, for example, critics were appalled, accusing him of weakening ‘the necessary inner war-readiness of the people’ and offering people ‘no moral or artistic gain’. Still other artists resorted to self-censorship. CRW Nevinson’s Paths of Glory 1917 focused on ugly corpses lying face down in the mud, stripped of dignity and individuality, strewn across a barbed wire landscape. When the Department of Information attempted to censor the painting, Nevinson hung it in the Leicester Galleries, London, with a piece of brown paper obscuring the dead bodies on which was written ‘CENSORED’. As in the three figures in the background of Nevinson’s The Doctor 1916, viewers of war art had three responses: staring, peeping, ignoring.

Artists such as Dix and Nevinson understood that art was a weapon of war. As with all weapons, it changed over time. This was why Orpen’s painting To the Unknown British Soldier in France had a third incarnation. In 1928, five years after it had originally been painted, Orpen painted over the shell-shocked soldiers and putti. All he left in the painting was a lone coffin lying in the Hall of Peace. The two shell-shocked soldiers who had been the subject of Blown Up were there only symbolically: one of the mad soldiers’ helmets rests on top of the coffin. If you look really carefully at his painting, though, the spectral figures of the emaciated soldiers are beginning to show through.

William Orpen, To the Unknown British Soldier in France 1921–8, oil paint on canvas, 154.2 x 128.9 cm

© Imperial War Museum

Aftermath: Art in the Wake of World War One, Tate Britain, Tate Britain 5 June – 16 September.

Joanna Bourke is Professor of History at Birkbeck, University of London and author of War and Art: A Visual History of Modern Conflict, published by Reaktion Books.