Lisa Brice in her London studio, 2017

Photo: Adam Davies

AÏCHA MEHREZ The women in your paintings are often figures taken from art history, personal photographs, magazines and the internet, and recast as self-assured characters enjoying a cigarette, escaping the heat for a beer or having a chat. Why is that?

LISA BRICE As a figurative painter it is significant that historical figuration seems invariably created by white men for an audience of predominantly white men. Sometimes the simple act of repainting an image of a woman previously painted by a man – re-authoring the work as by a woman – can be a potent shift in itself. Inserting props such as cigarettes or bottles of alcohol (as seen in Edouard Manet and Félix Vallotton’s paintings), or using strong colour to tweak the slant of eyes or mouth can further transform the figures from objectified to quietly self-possessed, matter-of-fact or provocative subjects.

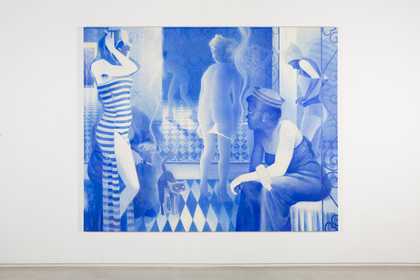

At times, this transposition rescues previously isolated figures of women from the lonely confines of a renowned art historical painting and gives them a new existence in a fresh grouping of other women, who are ‘freed’ in the same way. In their new setting, the women begin to play off one another. Perhaps a conversation is set up between generations, such as in my painting Between This and That 2017, where the art historical matriarch Gertrude Stein (as originally portrayed by Picasso in 1906) and Vallotton’s unnamed seated figure (possibly the performer Aïcha Goblet) from The White and the Black 1913 are brought into the same room. No longer isolated, a conversation is implied, but about what remains ambiguous.

Lisa Brice, Between This and That 2017, synthetic tempera (Flashe), gesso and ink on canvas, 198 x 244 cm

© Lisa Brice, courtesy the artist and Salon 94, New York. Photo: Jeff Elstone

AM Where do the ideas for your paintings come from?

LB For me, the art historical references in my current work represent my London life, mixed with references from my life experiences in both Trinidad and South Africa. It’s a mash-up of sorts, the result of the last 19 or 20 years spent moving between the three – a peripatetic existence.

I grew up in South Africa during a particularly volatile time in the country’s history and that still informs what I am drawn to and identify with. Wherever I am in the world, I still perceive things through that lens, which is an inherently political one, even if not directly related to politics.

In 1998, I arrived in London to do a residency at Gasworks Studios, where I met painters Godfried Donkor and Johannes Phokela, among others. There was a lively conversation in contemporary painting at the time, informed by all the incredible art historical paintings that I had previously seen only in books but which were now easily accessible in museums in London and Europe.

While at Gasworks I met Charlotte Elias who invited me to do a workshop in Trinidad along with Donkor and 20 other local and international artists in 1999, followed by a month-long residency the year after with Peter Doig, Chris Ofili and Andy Miller. I formed bonds with Trinidadian artists Embah (Emheyo Bahabba, a close friend and mentor who passed away two years ago), Che Lovelace and Adel Todd, to name a few, and I found that painting had a relevance and vitality that felt current.

AM With this mixture of influences in mind, why does a specific tone of blue recur so often in your work?

LB I did my first blue drawing in an attempt to imitate the blue light of neon signs, which led to trying to capture the fleeting colour of twilight in paint, the transitional gloaming hour. It has gone on to accumulate further meaning as the work has progressed. I associate it with the Trinidadian ‘Blue Devil’, a formidable Carnival character. Masqueraders are emboldened by a coating of cobalt blue paint, possibly made originally from Reckitt’s Blue powder, which is found throughout the colonies of the British Empire for bluing whites and is also associated with skin bleaching. This notion of a masked identity was employed during slavery, when the character was born, freeing the revellers from accountability.

Similarly anyone who has had the experience of playing J’ouvert (French Patois for ‘Daybreak’) – the nocturnal ritual that celebrates the beginning of Carnival – could testify to the liberating transformation of being covered in mud or coloured paint, released from the usual perception of oneself and others.

In my work this colour can suggest skin veiled in paint or tinted mud, obscuring naturalistic skin tones and interrupting an easy or preconditioned reading of the subject along ethnic lines. This all reinforces the idea of transformation and adds to the ambiguity of the narrative.

AM What drives you to cultivate this sense of uncertainty in your work?

LB I am drawn to the ambiguity that people and places can hold. Sometimes the compositions of my paintings feel like cinematic outtakes: the moments between directed actions, when the figures are ‘on their own time’, self-involved, performing only for themselves or one another. There are infinite possibilities embodied in these transitional states of being, which could also be a time of day, or adolescence, or gender, or rooms that feel like threshold spaces – thinly veiled interiors with glimpses of the exterior, grilles or indoor plants, typical in the tropics. These are all thrilling states – a kind of magical suspension.

The uncertainty inherent in the medium of painting itself appeals to me too – where the painting will take me regardless of what I might have originally intended. Reaching that ultimate moment when the work starts to hum… that is the spur that keeps me working through all the frustrating stages of the work looking really bad!

Art Now: Lisa Brice, curated by Aïcha Mehrez, Assistant Curator, Contemporary British Art, Tate Britain, until 27 August. This is an edited version of a printed interview available during the exhibition.

Lisa Brice is an artist who lives and works in London.