I am desperately in need of the bricks … All we need is bricks, PLEASE.

Barbara Hepworth, 19681

By the time she reached what would be her last decade in 1965, Barbara Hepworth was firmly established as one of Britain’s most prominent artists. In 1959 she had been the first British artist to win the Grand Prix at the São Paulo Biennial, surpassing the successes of Henry Moore, who had won the International Sculpture Prize in 1953, and Ben Nicholson, who was awarded the International Painting Prize in 1957. Such was this achievement that noted critic and long-time Hepworth supporter Herbert Read wrote to congratulate the artist, saying ‘the prize is the great event. You need have no more worries’.2 Although the work she made between 1965 and 1975 was not always as critically celebrated as her previous output, Hepworth continued to be successful in other ways during this period, producing and selling significant bodies of work in marble and bronze and holding a major retrospective at the Tate Gallery in 1968.3 In this exhibition she presented recent metal works alongside her highly praised early carvings, demonstrating an increasing experimentation with materials. In a film documenting the exhibition she reads words initially written for a British Council talk in 1961, noting that ‘in always remaining constant to my conviction about truth to material, I have found a greater freedom for myself’.4 Later in this talk she discussed her engagement with metal in more depth: ‘I found out the nature of its construction and forced it to express what I wanted by its nature and not against its nature’.5

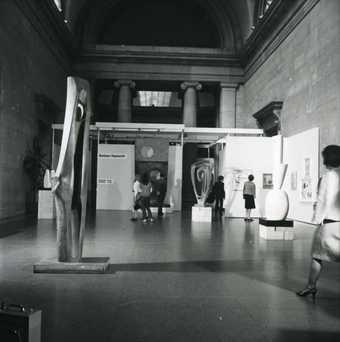

Fig.1

Installation view of Barbara Hepworth, Tate Gallery, 1968

Tate Archive

Works by Barbara Hepworth © Bowness

Photo © Tate

Fig.2

Carol Bove

Coral Sculpture 2008 (foreground) and Heraclitus 2014 (background)

© Carol Bove

In addition to her experimental approach to materials, this filmic record of the exhibition shows Hepworth staging her works in new ways. The grand neoclassical architecture of Tate’s Duveen Gallery was divided using white angular screens, with white wooden lengths running above the panels holding lighting equipment. Within these smaller domestic-sized spaces Hepworth placed many of her sculptures on plinths made of concrete blocks, with the others positioned directly on the floor. By rejecting the plain, white-painted wooden stands traditionally used to present sculpture Hepworth shifted the plinth from a neutral display mechanism to something engaged with by the artist’s hand. Throughout the slightly labyrinthine exhibition were pot plants, which reinforced the unusual sense of domesticity, as can be seen in the installation views of the show (fig.1). The concrete blocks, and indeed the plants, feel strangely contemporary now; artists such as Carol Bove, Isa Genzken, Rachel Harrison and Sarah Lucas, among others, have made work that incorporates the plinth into their sculpture, rather than use it merely as a support. Bove, for example, has created sculptures that feature natural materials fused to bespoke display mechanisms, skirting the boundary between art object and exhibition furniture (fig.2).6 How and why Hepworth chose to position her sculpture in this way in 1968 can be better understood through close reading of the extensive correspondence relating to the exhibition held in the Tate Archive.

On 17 January 1967 Hepworth sent an initial letter to Tate director Norman Reid confirming her retrospective at Tate for March the following year, and was already thinking practically: ‘working backwards from the exhibition, say the work to be there or available March 68 (including all the cleaning, restoration, setting up etc.) there is not too much time’.7 At this point she outlined key lenders – private collectors and museums – and works that she felt were crucial to the exhibition. A letter soon after, on 30 January 1967, suggests she had received confirmation from Reid and begins to discuss plans for the catalogue contributors. She asks Reid to write for Tate and suggests Nicolete Gray to contribute a text about her early years. The third contributor she suggests is not specified (‘I have more and more felt that perhaps three contributions might be made’),8 but that Dr Rudi Oxenaar from the Kröller-Müller Museum in Otterlo is eventually decided upon is perhaps unsurprising given the success of her recent exhibition there, Barbara Hepworth: Retrospective 1935–64, a success underscored by Reid’s approval in a concurrent letter of 26 January 1967: ‘And wonderful the Kröller-Müller show – sculpture looks at its best there’.9 By 2 March 1967 the Tate retrospective had been assigned to Ronald Alley, Keeper of the Modern Collection, and Hepworth wrote to him with lengthy lists of loans to be requested, leads for possible research and details of collectors or museums from whom she had already sought loans, the latter including Oxenaar at the Kröller-Müller.

After the initial loan negotiations Hepworth turned her attention to the exhibition design. On 4 August 1967, after discussing loans, the appointment of architect Michael Brawne as exhibition designer, the shipping and the catalogue, she wrote to Alley: ‘The real burden will be putting everything into first class order and getting exactly the right plinths’.10 She discussed how her shipping agents offered this service and proposed that if they fabricated the plinths it could ‘take a great load off the Tate personnel’.11 Alley’s reply contains no mention of plinths, but does confirm Brawne as the exhibition designer, leading Hepworth to persist in her next letter, ‘I am very thrilled that he [Brawne] will be remodelling the exhibition space and as I saw Mr. Gibbard, manager of the Morris Singer Foundry and Mr. Wirth yesterday, I can give you the latest specifications for height of plinths, so that Mr. Brawne could build the exhibition round the major pieces.’12 This shows the emphasis Hepworth placed on plinths within the overall exhibition design, and she pursued the point later in the same letter: ‘I think we must discuss the whole question of plinths’.13 While it is obvious that the heights of the plinths would have an impact on the presentation of the works, the ‘whole question of plinths’ perhaps seems more pertinent when considering this period of British sculpture, which casts the phrase in a particular light.

Fig.3

Anthony Caro in Anthony Caro: Sculpture 1960–1963, Whitechapel Art Gallery, 1963

One of the stars of 1960s British art was Anthony Caro who, following respectable successes with his modelled bronze figurative work of the 1950s, exploded onto the scene in 1963 with an exhibition of recent work at the Whitechapel Art Gallery, London. These pieces were made of welded steel, painted bright colours and placed directly on the floor. The abandoning of the plinth was inspired by Caro’s wish to make the encounter with sculpture more direct: he encouraged people to relate to the works bodily by placing them in the same architectural frame and on the same plane as the viewer, rather than elevating them on a plinth (fig.3). This was explicitly stated in the introduction to the 1963 show by Whitechapel director Bryan Robertson, who noted: ‘Caro’s sculptures stand on the floor without the intervention of pedestals or bases. Their impact is direct and immediate. Caro dislikes the idea of sculpture presented with artificial aids, separate from the ground – and from life, and so trapped inside an archaic aesthetic vacuum’.14 The inferences here are clear. Pedestals are artificial and affected, and old-fashioned. Both of these criticisms would have struck a chord with Hepworth as an artist who had been at the forefront of various avant-garde movements: direct carving in the 1920s, the development of constructive abstraction in the 1930s, collaborations with scientists and architects in the 1937 publication Circle, and the establishment of the St Ives school in the 1940s. Authenticity was also key to how she framed her work – most prominently within the ‘truth to materials’ doctrine with which she had been associated throughout her career.15

Fig.4

Installation view of Barbara Hepworth: An Exhibition of Sculpture from 1952–1962, Whitechapel Art Gallery, 1962

Works by Barbara Hepworth © Bowness

Traditional plinths had become unfashionable around this time. In 1962, the year before Caro’s exhibition, Hepworth had had her own show of seventy-five recent works at Whitechapel Art Gallery, at that time her largest exhibition in the UK, and had been experimenting with the display, although not to the extent of Caro’s radical move of abandoning the plinth entirely. Here Hepworth tried different colours and styles of plinth, some mirroring the skirting boards of the gallery space, and included those she had in her studio at Palais de Danse, St Ives, which were set on wheels to keep them moveable (fig.4). This mixture of plinths was not particularly successful, and Hepworth would later indicate her dissatisfaction with the wheeled plinths in particular, noting that they do ‘not look nice as they have wheels which stick out like splayed feet’.16 The Whitechapel Art Gallery continued to stage pioneering displays of sculpture following Caro’s show and in 1965 presented the New Generation sculpture exhibition featuring British sculptors who had taken Caro’s lead and moved work off the plinth and onto the ground. These included artists such as Phillip King and William Tucker, with whom Hepworth was familiar, mentioning them in her letters and having sat as a Tate trustee during the period when their work was acquired by the museum.

For Hepworth in the summer of 1967, ‘the whole question of plinths’ had been evaded long enough. She wrote to Tate’s deputy keeper Judith Cloake on 30 August 1967, stating in no uncertain terms that ‘The most urgent thing – I would like to have a ruling about; is about the plinths’, anxious that they should be designed ‘well before’ the installation.17 It is clear that Hepworth was considering the plinths for her works in great detail, and that at this stage she was considering more traditional wooden bases, as she closed the 30 August letter offering the woodworking services of Pollard & Co., a firm associated with her foundry. Cloake’s response puts the matter firmly in the hands of the exhibition designer, ‘We have left the question of the plinths for your sculptures in the capable hands of Michael Brawne’, which mollified Hepworth somewhat, with Cloake also suggesting that with enough time and the specifications the Ministry of Works could fabricate them.18

The end of the year was taken up with debate on the inclusion of some works and exclusion of others, as well as Tate’s concerns over the increasing number of pieces to be shown. The issue of plinths arose again in January of 1968 when Hepworth wrote to Brawne, having met him for the first time in October to discuss the show, opening her letter, ‘I have phoned you two or three times but you seem to have been away’. She goes on to say, ‘I am enclosing a list of the base measurements of all the Tate sculptures as I rather think they should be transferred onto brick to suit your décor’.19 Brawne responds that he will let her ‘see a preliminary exhibition design very soon’, so it is not clear what décor she is referring to at this point. It is likely that they discussed the design of the exhibition in broad terms during Brawne’s visit to St Ives with Alley in October 1967. That his décor would have been largely in the modernist vein is likely given his interests. In 1965 Brawne had published The New Museum, an important survey of current art museum practices that focused on curatorial details including the materials of the floor and surroundings, the architecture and the display designs. In the introduction to this international survey, which included new museums from the Museum of Modern Art, Rio de Janeiro, to the Le Corbusier-designed National Museum of Western Art, Tokyo, Brawne noted that ‘each of these visual and tactile experiences is intended to sharpen the encounter between object and observer … since the museum is a medium of communication these are important intentions’.20 Curator and art historian Penelope Curtis has noted, however, that Brawne’s design for Henry Moore’s retrospective at the Tate Gallery later in 1968 kept more closely to a grand sculpture display on traditional plinths, suggesting that Hepworth was in part the driver of the experimental exhibition design.21

Fig.5

Installation view of Barbara Hepworth Gift, Tate Gallery, 1967

Tate Archive

Works by Barbara Hepworth © Bowness

Photo © Tate

In the event, the white angled screens that were used for Hepworth’s exhibition were not designed by Brawne. Instead, they were existing screens that had previously been used to divide up the Duveen Gallery, probably first in the Young Contemporaries exhibition of 1967.22 Prior to this, similar screens had been designed in modular form by architects Peter and Alison Smithson for the exhibition Painting and Sculpture of a Decade 1954–1964, organised by the Gulbenkian Foundation, Lisbon, and held in 1964 at the Tate Gallery. The screens were remarked upon at the time in a review of the exhibition in the Guardian by Guy Brett, who noted, ‘The booming halls of the Tate have been cleverly, if rather plainly, brought down to human scale by mazes of screens’.23 Brett’s identification of the grand neoclassical hall of the sculpture gallery as ‘booming’ and his praise of using screens to bring them to ‘human scale’ reflects a general negativity towards the traditional architecture of the Tate Gallery and a move away from the formality of the museum. Prior to Hepworth’s exhibition, the Young Contemporaries screens had been revived in November 1967 for the display of the works gifted by Hepworth to Tate (fig.5). In a letter to Hepworth in December of that year, Herbert Read echoed Brett’s sentiments about the display:

Then we went down to the Sculpture Gallery, where all your pieces are now displayed together, in their own alcove. Very impressive. Of course, nothing will ever look perfect in that awful gallery, but Norman has done his best and it is quite beautiful.24

Fig.6

Installation view of Barbara Hepworth Gift, Tate Gallery, 1967

Tate Archive

Works by Barbara Hepworth © Bowness

Photo © Tate

Installation photographs of the Hepworth gift display and her subsequent retrospective reveal that a number of the structural designs within this space were retained from one to the other. The gift display was, as Read notes, in an alcove made using the white angled panels in the first half of the south gallery (fig.6). The second half of the south gallery held works from the Tate collection, including a number by Henry Moore, such as King and Queen 1952–3, cast 1957 (Tate T00228) which had been acquired in 1959. The white angled screens remained, or were reinstalled, during the 1968 retrospective and the first alcove featured two-dimensional works by Hepworth. The second half of the south gallery held larger works during the retrospective, some on low block plinths and some presented directly on the floor. Perhaps most prominently, the large central screen with elevated connecting horizontal white bands holding light tracks remained in front of the columns in the central octagon. This provided the entrance wall to the retrospective, with ‘Barbara Hepworth’ writ large to the left of Squares with Two Circles 1963 (fig.7). This work had been acquired in 1964 so would not have been included in the display of the 1967 gift, but was presented in almost exactly the same location in the concurrent collection display.

Fig.7

Installation view of Barbara Hepworth, Tate Gallery, 1968

Tate Archive

Works by Barbara Hepworth © Bowness

Photo © Tate

Fig.8

Installation view of Barbara Hepworth, Tate Gallery, 1968

Tate Archive

Works by Barbara Hepworth © Bowness

Photo © Tate

The earlier images of the gift display show that this wall acted as the end of the collection display featuring Hepworth and Moore and the entrance to the exhibition Recent British Painting: Peter Stuyvesant Collection. This exhibition was held in November and December 1967 and the title can be made out with close reading on the central panel to the left of Squares with Two Circles. The other main difference between the gift display and the retrospective in the south gallery is the plinths. The gift display presented works on traditional wooden plinths painted white, whereas in the retrospective almost all works are shown on block plinths. From the rotunda into the north gallery, installation images of the retrospective show the angled white screens continuing, arranged by Brawne to create a labyrinthine display and neutralising the neoclassical architecture. On 19 February 1968 Brawne sent copies of the layout to Cloake, Alley, Hepworth and fabricators Beck and Pollitzer for an initial quote, noting to Cloake, ‘Aside from Beck and Pollitzer’s installation, we must leave some money aside for blockwork and shrubbery’.25 The quote from Beck and Pollitzer excludes these items as well as another from the original plan – a muslin ceiling, which would have further added to the domestic nature of the exhibition design by completely concealing the grand height of the neoclassical galleries. In the event, and probably due to concerns over the rising costs of the exhibition, this was excluded, although some sections of the show did feature a white ceiling of indeterminate material, to similar effect (fig.8).26

By 26 February 1968 Hepworth was set on block plinths and wrote somewhat frantically to Brawne on this matter:

I am desperately in need of the bricks, which my men could build for me, the moment we could have them. This is a matter of great urgency, as by March 11th I must have installed the big ones in situ, as there is a long colour television recording for BBC2 and it is imperative that I have enough up, of the large ones, for them. At least by the end of next week they complete the film, before cutting, as it is to go out on March 30th. All we need is bricks, PLEASE.27

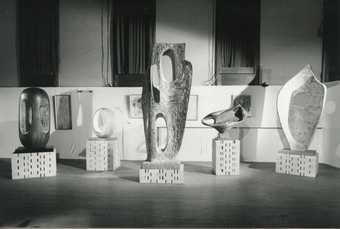

Fig.9

Installation view of Hepworth’s retrospective at the Rietveld Pavilion, Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, 1965

Works by Barbara Hepworth © Bowness

She closes her letter with, ‘Thank you so much, it is now a question of time for me. My men are already up there and we are totally held up until we have bricks’.28 A note from Cloake dated 1 March reveals that the brick plinths were not a cost-saving device, listing them as an additional unforeseen cost to the rapidly increasing exhibition budget and noting them as partially recoverable.29 There were hopes that the bricks could be sold on or reused, although neither of these eventualities came to pass. Cloake received an apologetic letter in August from the Arts Council declining to purchase them, and they were not suitable for re-use in the subsequent Henry Moore exhibition, Hepworth noting in a discussion on their salvaging that ‘Harry said he did not like them’.30 This could have been due to their modernist style, at a time when Moore’s work returned to traditional monumental bronze more suited to a conventional plinth, or because they were not ideal even in themselves. Discussing the costs following the opening, Hepworth wrote to Reid, ‘Michael Brawne was busy trying to sell the blocks after my exhibition and this would not be at all difficult except for the fact that they are rather poor quality. I will speak to Mr. Wirth as the reorder of better looking blocks for the tops of the plinths was £43 and I did offer to buy them.’31 This demonstrates the significance to Hepworth of this style of plinth, her willingness to extend herself financially to achieve the result she wanted and her commitment to a particular aesthetic specifically in relation to the plinths.

Hepworth clearly intended to disguise the ‘awful’ space of Tate’s Duveen Gallery, and Curtis has drawn parallels between elements of the final exhibition design and the architectural style of the modernist pavilion, from the lowered ceiling to the angled white screens. As Curtis notes, this may have been due to Hepworth drawing on her experiences of showing work at Kröller-Müller Museum in 1965, the exhibition that Reid had so praised during the inception of the Tate retrospective (fig.9). This had been her most recent and comprehensive exhibition until the 1968 show, and had included forty-five sculptures from a cross-section of her career. Most significantly, the exhibition presented a large body of work in and around the Rietveld Pavilion, a modernist structure that had been designed in 1955 by Dutch architect Gerrit Rietveld for the Third International Sculpture Exhibition held at Sonsbeek Park in Arnhem in the Netherlands. At the end of the exhibition the structure, known then as the ‘Sonsbeek Pavilion’ was dismantled, but it had garnered great admiration within the architecture community, and following Rietveld’s death in 1964 a group of architects petitioned to have it rebuilt. It was permanently sited at the Kröller-Müller Museum in 1965 and Hepworth’s was the inaugural exhibition.

In January 1968, the same month as Hepworth’s decision to use bricks in the retrospective, the formal invitation to Rudi Oxenaar to contribute to the exhibition’s catalogue was made by Reid, who wrote:

At Barbara Hepworth’s suggestion I am writing to ask whether you might be prepared to write a short essay for the catalogue of her exhibition, on the placing of her sculptures at the Kröller-Müller Museum. It could deal briefly with the formation of your collection of her work and with the siting of her sculptures out of doors and in relation to the Rietveld Pavilion. As you know, she is especially fond of your museum and delighted with the way you have displayed her works.32

Reid’s letter highlights some of the reasons Hepworth may have particularly liked this presentation of her work. Placing works ‘out of doors’ was, as Tate curators Matthew Gale and Chris Stephens have noted, ‘one of Hepworth’s abiding concerns’,33 and in 1963 she explicitly outlined her ideal scenario for presenting sculpture, stating in her essay ‘Artist’s Notes on Technique’ that ‘I always envisage “perfect settings” for sculpture and they are, of course, mostly envisaged outside and related to the landscape’.34 This desire would have been fuelled by Hepworth’s acquisition in 1949 of Trewyn Studio in St Ives, which had a marble yard and garden enabling her to sculpt outside. She used the garden as a viewing area for completed works, and many works displayed now in the Barbara Hepworth Museum Sculpture Garden are placed as Hepworth installed them, among the plants. The inclusion of plants in the 1968 retrospective, selected by Brawne and ‘most generously’ purchased for the exhibition at a cost of £70 by the Friends of the Tate, could be read as a gesture by Hepworth towards her desire to place works in the landscape.35

Fig.10

Barbara Hepworth in the garden at Trewyn Studio, 1956

Works by Barbara Hepworth © Bowness

Photo Studio St Ives © Bowness

There are further similarities between the 1968 exhibition design and the 1965 Kröller-Müller show, as the Rietveld Pavilion itself was comprised largely of exposed industrial blocks. In keeping with the structure, Hepworth’s works were shown on plinths made with blocks, in this case mortared together rather than stacked loose as in the Tate retrospective. Although her use of blocks for plinths in the latter could have been informed by the Rietveld Pavilion exhibition, photographs show her placing work on bases built in this manner in the Trewyn Studio garden as early as 1956 (fig.10). Here Hepworth is shown alongside works, some on plinths made of blocks fixed together and others loosely stacked. It is plausible that this was a simple makeshift way to present sculpture in her home and studio, which then subsequently gained aesthetic resonance when placed within the modernist structure of the Rietveld Pavilion. It is also possible that bringing the way she staged works at home into the public art gallery helped to reduce further the connotations of the traditional elevated artwork which Caro and the New Generation sculptors had so effectively dismissed, and encouraged closer and direct engagement with the visitor. Rather than alluding to the natural world, the use of pot plants may have been intended to underscore this sense of the domestic and informal, encouraging viewers to feel ‘at home’ and communicating the feeling of living with art of which Hepworth had been an advocate since the 1930s.36

Fig.11

Installation view of Exhibition on the Occasion of the Conferment of the Honorary Freedom of the Borough of St Ives on Bernard Leach and Barbara Hepworth, St Ives Guildhall, 1968

St Ives Archive: Cyril Gilbert Collection

Works by Barbara Hepworth © Bowness

Photo © mk

Although not particularly well received by critics, the exhibition was a public success, documented in film by the BBC and receiving many visitors, leading Hepworth to write to Brawne that ‘the attendances are high and the sales of the catalogues most excellent’.37 In a previous letter she had thanked Brawne for ‘the excellent cases you provided for me and the arrangement of the screens’, continuing with further praise: ‘I also thought your idea of putting the four bronzes on the steps was very rewarding. Thank you also for the excellent plants you found.’38 From this careful designation of plaudits, it seems clear that Brawne was responsible for the cases and the layout of the pre-existing screens. While he is credited with finding the plants, he is not credited with the idea of including them as he is for the placing of works on the steps outside, which supports the suggestion that the plants were an idea that came from Hepworth. The plinths are entirely left out of this letter, although they clearly comprise a significant part of the exhibition design, which Hepworth expressed her delight with in letters to Brawne and Reid. From this, it seems likely that the inclusion of block plinths in the gallery environment was a development of Hepworth’s own.

In fact, at her next major exhibition the block plinths made another appearance, this time with even more attention paid to them even though the exhibition was swiftly conceived and constructed. In September 1968 Hepworth and the potter Bernard Leach were given the honorary freedom of St Ives. An Exhibition on the Occasion of the Conferment of the Honorary Freedom of the Borough of St Ives on Bernard Leach and Barbara Hepworth was held at St Ives Guildhall between September and October 1968. Hepworth placed all of her sculptures inside the gallery on plinths made of blocks smaller and more uniform than those in the Tate exhibition but again stacked loosely rather than mortared together. Installation images show that she used these factors to experiment with the placing of the blocks and the gaps between them, creating geometric patterns with the squared absences (fig.11). In this display Hepworth succeeded in appropriating the traditional plinth and blurring the line between exhibition furniture and artwork.

Fig.12

Installation view of A Greater Freedom: Hepworth 1965–1975, Hepworth Wakefield, 2015–16

Works by Barbara Hepworth © Bowness

The question of where sculpture stops and objects begin is a complex one, raising issues of the values placed on objects and the definition of sculpture that continues to be engaged with by sculptors and installation artists today. It also raises curatorial questions of the often assumed neutrality of conventional white plinths within museum presentation. When in 2015 the Hepworth Wakefield reprised the block plinths and plants in a display of work from Hepworth’s last decade, the effect was striking compared to the standard white painted wooden plinths of the art museum (fig.12). The different material highlighted the texture and specificity of the sculptural materials used. Set against the inclusion of plants, this prompts a consideration of the history, life and repurposing of materials, encouraging visitors to note, for example, the relationship between the plants and the wooden sculptures. This sensitivity to materials and the ‘whole question of plinths’ reveals Hepworth, even in later life, to be engaged with artistic debates on the way that sculpture is perceived, ones that remain of interest to artists today.