In 1975 Jeffrey Deitch curated a large exhibition of contemporary art at the Fine Arts Building in New York City. The exhibition was titled LIVES: Artists who deal with people’s lives (including their own) as the subject and/or medium of their work.1 The title was very carefully chosen: this was not necessarily biographical or autobiographical work; lives may be the subject of these works but they could also be understood as their medium. This focus on lives, or on the stories artists make from lives in many cases, is striking because American art of the 1960s – minimalism and pop in particular – is often seen as questioning the role of authorial intent in the understanding of the meaning of a work of art. These artistic practices subsequently impacted upon critical and art historical commentaries, which began to sideline the kind of biographical accounts of art making that had underpinned much of the rhetoric of earlier twentieth century art in the USA. As the critic Rosalind Krauss put it in 1977: ‘The significance of the art that emerged in this country in the early 1960s is that it staked everything on the accuracy of a model of meaning severed from the legitimatizing claims of a private self.’2 Although the various different struggles for rights claimed in the late 1960s in the name of gender, racial, and sexual identities brought questions concerning the relation between the private self and public sphere back onto the table, the ‘lives’ that Deitch’s show foregrounded did not represent a simple return to the idea that an artwork’s meaning stemmed from the artist’s biography, but rather questioned the way in which audiences often still insisted on reading works through life narratives. For example, Hannah Wilke’s Intercourse With… – a sound recording of her answerphone messages – told its listener less about Wilke or her work than it did about her audience’s desire to know more about her private life.3

This essay will focus on two works that, although not included in Deitch’s show, seem to play with a similar desire to complicate the way in which mediated life narratives are consumed by art audiences. The video tapes that Lynda Benglis and Robert Morris produced collaboratively between 1972 and 1973 – which exist today as the single channel video works Mumble (with authorship ascribed to Benglis) and Exchange (which is considered to be by Morris) – provide a particularly complex case study. Both tapes are made from material shot by both artists in Benglis’s and Morris’s studios, which have then been re-photographed from the playback on the monitor in multiple layers in a manner consistent with Benglis’s other video works of the period. Mumble is narrated by Benglis herself, while the soundtrack of Exchange is written by Morris but read by the poet Steven Koch. Both tapes at times suggest a narrative that never fully develops into anything like a story. They are fragmented and frustrating works.

Fig.1

Lynda Benglis

Parenthesis 1975

Cast aluminium and cast lead in velvet-lined wooden box

© Lynda Benglis

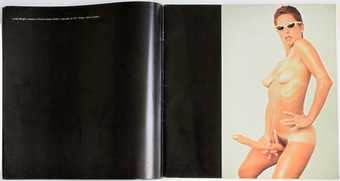

Fig.2

Lynda Benglis

Centerfold 1974

Advert published in Artforum, November 1974, pp.2–3

© Lynda Benglis

Benglis was included in Deitch’s exhibition and was represented in the catalogue by an image of her work Parenthesis 1975 (fig.1), a pair of brackets made from bronze casts of the double-ended dildo she had wielded in the notorious advert she placed in Artforum the previous year. The advert famously showed Benglis standing nude, her body tanned, oiled, and shining, eyes masked by bug-lensed shades, wielding the oversized sex toy (fig.2). The same photograph of Parenthesis was also used to announce two other exhibitions of her work in 1975, at the Kitchen and Paula Cooper Gallery respectively, which included Polaroid photographs of her and Robert Morris posing with the dildo under the title Secret. The bronze dildos are clear metonyms for the scandal that had accompanied the publication of the advert the previous year, and their reproduction on promotional material confirm that contemporary viewers would have been able to recognise the reference.

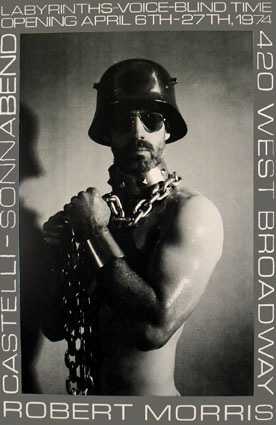

Fig.3

Poster for Robert Morris’s exhibition Labyrinths-Voice-Blind Time at Castelli-Sonnabend, 1974

© Robert Morris

The scholarship on Benglis’s work contains plenty of parentheses – the space in which one might make an aside that seems crucial to the argument yet somewhat unseemly to the flow of the sentence. Brackets also neatly place things together. Benglis is routinely bracketed with Robert Morris; her performance of gender in the Artforum ad is frequently compared with his in the poster for his exhibitions at the Castelli-Sonnabend Galleries in New York in 1974 (fig.3). Mira Schor memorably described the latter as an image in which Morris ‘turns himself into a penis, a GI helmet forming the head and biceps the shaft’, his eyes masked by mirrored aviator shades as he clutches a thick chain to his torso.4 This image, however, was something of a compensatory fiction. In a letter to his wife, the artist Carolee Schneemann, the filmmaker Anthony McCall commented at the time on the disparity between the statuesque image of Morris in the poster and the real life figure of the artist in the exhibition space – small of stature and dressed in tweed.5

The pairing of Benglis’s ad with Morris’s poster suggests its own story. It is a story that has been told many times, but it is crucial for understanding the video works that the two artists produced together at that time, and so it is rehearsed again here. Benglis sent her photograph to Artforum for inclusion in an article on her work by the critic Robert Pincus-Witten, only to have it refused for publication.6 As a result she had her gallery pay for the image’s inclusion in the magazine as an advert, which resulted in a letter of protest from several of the magazine’s regular contributors and the eventual resignation of the editors Rosalind Krauss and Annette Michelson, who went on to found the journal October (which contains no gallery advertising as an editorial policy).7 Krauss herself took the photograph of Morris for the poster that advertised his solo shows in 1974 and it was illustrated in the pages of Artforum that year. The fact that Morris and Benglis had bought the infamous dildo together and posed with it in the Polaroid photographs shown at Paula Cooper in 1975 have linked these two images together. Some have suggested that this visual relationship can be mapped onto a sexual one between the two artists, although more often than not this rumour is placed in the footnotes of the scholarship, in the gutter of the page.8

Fig.4

Robert Morris

Exchange 1973 (still)

Courtesy of the artist, Sprüth Magers and Castelli Gallery

© Robert Morris

There is almost no published factual information about the biographical links between Benglis and Morris – their so-called real or private lives – but the images and texts that surround them flirtatiously suggest an erotic relation. The narratives of the video tapes they made together underline this flirtation, but like the adverts and the Polaroids, convey the possibility that the relationship may be all representation. (The chronology here is unclear: the videotapes are dated before the publication or display of the Benglis photograph or Krauss’s image of Morris but they may have been made by that point or at least their production may have been envisaged). The suggestive narration of Morris’s Exchange, read by Koch (fig.4), recounts, ‘he had become obsessed with her face – heavy lidded eyes, full mouth, altogether dark and exotic countenance – that he was having dreams about her face, that […] he could think of nothing but her face,’9 and later in the tape, ‘This has been about love and competition’.

Fig.5

Robert Morris

Exchange 1973 (still)

Courtesy of the artist, Sprüth Magers and Castelli Gallery

© Robert Morris

Benglis only appears in Exchange as a still image that repeatedly punctuates the tape, first appearing after the description of ‘his’ infatuation with ‘her’ (fig.5). The image comes from an invitation card that features four photographs of Benglis as she made the video work Document 1972, in which can be heard the sound of the camera shutter used to take the images on the card. In each image Benglis’s face is centred frontally between two profile views that face one another on a television monitor behind her head, such that her face is actually reproduced twelve times in all on the card. Benglis’s hair is closely cropped and she wears a deadpan expression, while the collar of a black roll-neck sweater is the only clothing visible in the image. The different exposures create variation in tone and contrast across the four photographs. Although not as dramatically posed as some of her other publicity material, the image is nonetheless a staging of the self and, through its multiplication, suggests a splitting of the subject across multiple channels, drawing attention to itself as a reproducible representation of a video tape.

The ‘he’ conjured by the narrator of Exchange is in love with this image, not with a woman per se but with her representation. This mediation is made explicit in the narration, yet it is undercut by the third person form it takes and then also by the interjection of the first person to denounce its purple prose:

They move around one another, constantly circling about the tapes that stand between them. Feelings of love and anger are absorbed by the blotter of art. His image, her voice. They are cautious and attentive. Two wolves eying each other across a carcass. (aside) You’re going to have to get somebody else to read this, I just can’t speak this way.

In a dream he was dressed as a stormtrooper and she had four faces. He touched the photograph. ‘Your hands are like ice’ he said. ‘They’re always like that in a photograph’ she replied.10

The sentence marked as an ‘aside’ here is read in the same flat tone as the rest of the text, raising the question whether this supposed moment of spontaneity is also scripted. Incidentally, by suggesting that ‘he was dressed as a stormtrooper’ the text prefigures the publication of the photograph of Morris used for the Castelli-Sonnabend poster the following year.

The narrative of Exchange, then, suggests a romantic, or at least flirtatious, relationship between the two artists, an allusion also conveyed by Mumble. However, the dialogue between the two works may well be playing on what contemporary audiences expected to hear rather than being a revelation of their private lives. The art historian Anna Chave, in an essay that is foundational to the account offered here, has drawn attention to the particularly gendered way in which an artist’s career was shaped in New York at this time.11 Chave demonstrates the way in which men would build enabling narratives that protected them from accusations of over-intellectualism and bourgeois class alliances while women were placed into familiar and clichéd roles of victim, sex kitten, or matriarch by the media. The New York art world at the time was relatively small and in Manhattan itself the network of personal relationships was the subject of much gossip and intrigue. Mumble and Exchange are suggestive of the importance, at the time of their production, of the way in which these audiences (both those who knew the artists personally but also those who knew them through media portrayals or gossip) would project meaning on to them based on what they knew of their life narratives. Like the gossipy articles that filled the pages of low circulation artists’ magazines of the time, like Culture Hero (1969–70) or Art-Rite (1973–8), these works invited their audience to become – through media – part of a small coterie and asked sophisticated questions regarding art making and its audience on the lure of gossip.

Exchange and Mumble are autobiographical works, yet they constantly challenge the idea that life narratives can be unmediated.12 Both tapes open with a brief description of how the tape was made. This inclusion of the process of making represented an extension of the idea underpinning Benglis’s earlier poured polyurethane works, which were linked at the time by critics to the paintings of Jackson Pollock, who Morris had praised for being able to ‘recover process and hold onto it as the end form of the work’.13 Mumble was one of five videos Benglis produced in 1972 during a particularly prolific period of work in the medium. Many of these tapes are engaged in an exercise of self-observation, whereby Benglis interacts with her own image on screen or that of another person. Mumble begins with Benglis’s words:

This is a tape I made of Morris in my studio sometimes sometime in December. Yeah good. This was sometime in December. The noise you hear in the background is Robin Torreano who has a studio underneath my studio. She’s weaving.

Fig.6

Lynda Benglis

Mumble 1972 (still)

© Lynda Benglis

Unlike the detached third person pronouns of Morris’s tape, Benglis makes use of proper nouns throughout. From the start there are competing image layers in Mumble, different points of view. The tape was made by playing a reel on a monitor showing Morris smoking a cigar in her studio, then shooting a second tape of this monitor with her brother’s profile visible in front of the screen. This second tape is then played on the monitor and Benglis shoots Marilyn Lenkowsky in front of that tape (fig.6). None of the three protagonists need ever to have been in the same room at the same time to achieve this mise-en-abyme, an effect that Benglis created in most of her video work from the first half of the 1970s.

Exchange opens with an echoing voice that is difficult to make out, outlining the psychodynamics of the project: ‘How he used him, how he used her to understand his feelings … what he imagines his image represents to her, what her image represents to him.’14 Like Benglis, Morris had long been interested in the inscription of the process of making into his finished works. This was clearly articulated in process-based works like Continuous Project Altered Daily 1969, but stretched back as far as early objects such as Box with the Sound of Its own Making 1961 and Card File 1962.15 A more clearly audible description of the process of collaboration follows this introduction and makes reference to the making of Mumble. This monologue, read by Koch, was printed in its entirety in the journal Avalanche in 1973:

This is a tape he made of a tape she made of a tape he made in her studio. This is a tape he made of a tape she made. On screen is her tape of his tape. His tape is the last image in the background which she re-photographed with other faces. The tape is of that. His tape was raw material. This tape on screen is raw material. Re-photographing his work made it her work. Or commenting on it made it her work. Or both. She is heard but never seen. Nothing here has been re-photographed. Can it then be raw material?

She suggested a dialogue. He was to make a tape and she was to answer it, and he was to answer that. He made a tape that he used in her answer.

This is a tape he made. He made it for her, as much as one can make one thing for another … She was not in the studio at the time it was made. Many things have been edited out.16

Although this text seems fairly matter of fact, as it continues it makes reference to almost sixteen tapes in total that are not evident in the ‘finished’ versions of either Mumble or Exchange. This contradiction between what the viewer is told and what can be seen immediately sets up the narrator as an unreliable source.

Fig.7

Robert Morris

Still from Exchange 1973, showing an image of Morris’s earlier work Site 1964

Courtesy of the artist, Sprüth Magers and Castelli Gallery

© Robert Morris

The exchange of tapes here is of course a gendered one. While both artists had achieved significant success, both critically and commercially, Benglis was highly conscious of her position as a ‘woman artist’. The position of women in the art world was being systematically investigated at this time not only by art historians such as Lynda Nochlin and Cindy Nemser but also by artists themselves. Benglis was teaching as a visiting lecturer at the California Institute of the Arts throughout the early 1970s alongside artists such as Miriam Schapiro and Judy Chicago, who were consistently working through the causes and consequences of gender inequality in the art world in both their teaching and practice.17 The tapes narrate the way in which male and female artists find themselves jockeying for power and especially the way in which male artists come to cover-over and obscure the achievements of women. Both videos show bodies obscuring those of others, getting in the way, covering their work. Exchange includes a number of shots of photographs that Morris kept on his studio wall: a headshot of Buster Keaton, two racing cars on a tight bend, and figures stood within Morris’s work Steam 1967. Prominent among these photographs is documentation of Morris’s performance work Site 1964, in which he lugged a series of screens around the stage before revealing the body of a recumbent nude Carolee Schneemann posed as Edouard Manet’s Olympia (fig.7). Schneemann’s role in this work as collaborator rather than as simple object of the gaze has long been obscured – she was both artist and muse but could only be understood as the latter. In Exchange, Morris’s juxtaposition of this image with the narration telling of how he cut Benglis from parts of the tape, or how she obscured his speech, seems to be a recognition of the mistakes of that past collaborative endeavour. The exchange that the two tapes supposedly document is not an ideal collaboration but demonstrates the way in which any act of working together is pitted against self-interested emotions.

Fig.8

Lynda Benglis

Now 1973 (still)

© Lynda Benglis

The relationality of the exchange as it is laid out in the introduction to both tapes places this collaboration at a remove from the most influential account of Benglis’s video work. Rosalind Krauss’s much reproduced text ‘Video: The Aesthetics of Narcissism’ (1976) argues that video as an artistic medium might be defined through the doomed psychological state of narcissism.18 She makes this claim by looking at works of art that use the camera and the live feed of the monitor as a mirror, and describes Benglis’s 1973 tape Now as an paradigmatic example (fig.8):

The tape is of Benglis’s head in profile, performing against the backdrop of a large monitor on which an earlier tape of herself doing the same actions, but reversed left and right, is being replayed. The two profiles, one ‘live’, the other taped, move in mirrored synchrony with one another. As they do, Benglis’s two profiles perform an autoerotic coupling, which, because it is being recorded, becomes the background for another generation of the same activity. Through this spiral of infinite regress, as the face merges with its double and triple reprojections of itself merging with itself, Benglis’s voice is heard either issuing the command ‘Now!’ or asking, ‘Is it now?’19

Benglis stretches her tongue to reach out to the image that returns the gesture on the monitor – they will never connect, never spark, as she falls into herself. Krauss saw within this work Benglis becoming transfixed by her own image and finding her identity drowned in the pool of the magnetic signal like narcissus. She writes:

the tape enacts a collapsed present time … the nature of video performance is specified as an activity of bracketing out the text and substituting for it the mirror reflection. The result of this substitution is the presentation of a self understood to have no past, and as well, no connection to any objects that are external to it. For the double that appears on the monitor cannot be called a true external object. Rather it is a displacement of the self that has the effect … of transforming the performer’s subjectivity into another, mirror, object.20

This turning of subject into object is linked by Krauss to the use of mass media by artists. In this passage she is clearly making reference to the public debate in the letters page of Artforum concerning Benglis’s advertisement with the dildo. In the essay Krauss writes that she wishes to make a connection:

between the institution of a self formed by video feedback and the real situation that exists in the art world from which the makers of video come. In the last fifteen years that world has been deeply and disastrously affected by its relation to mass media … the demand for instant replay in the media – in fact the creation of work that literally does not exist outside of that replay, as is true for conceptual art and its nether side, body art – finds its obvious correlative in an aesthetic mode by which the self is created through the electronic device of feedback.21

Krauss goes on to discuss Jacques Lacan’s concept of the mirror stage and suggests that narcissistic video work does not understand the gap between the idealised imago and the self and as such is locked in the frustration that such splitting brings forth. This, then, is to suggest that Krauss wishes artworks to somehow represent psychological states that are normative rather than pathological – a sentiment that rubs against much of her subsequent work that questions the validity of sublimation.

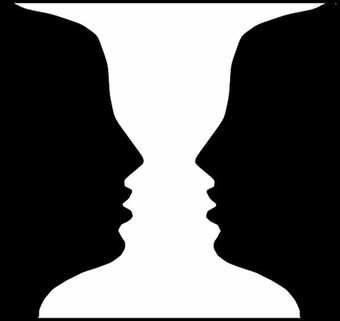

Fig.9

The Rubin Vase diagram

The art historian Ina Blom has suggested in a more recent essay that the image captured in Mumble is an allusion to the Rubin Vase perceptual diagram (fig.9), which demonstrates a breakdown of figure and ground (an image that features prominently in the opening pages of R.D. Laing’s The Divided Self (1960), a book that, as we shall see, was crucial to Morris’s thinking at this time).22 Like the Rubin Vase, reality and its representation cannot be easily distinguished within the feedback loop of video. This mode of subjectivity as entirely locked into a loop where life and its mediation cannot be separated was reflected elsewhere in the cultural milieu of the time. The poetry of Mark Strand – who provided one of the audio tracks for Morris’s 1974 installation Voice – provides a useful point of comparison as it has a particular affective resonance that is more ambiguously played out in Benglis’s and Morris’s tapes. His poem ‘The Story of our Lives’, published in 1973, clearly echoes the idea of the self formed by media in a manner where it is impossible to peel away representation from living:

1. We are reading the story of our lives,

as though we were in it,

as though we had written it.

This comes up again and again.

In one of the chapters

I lean back and push the book aside

because the book says

it is what I am doing.

I lean back and begin to write about the book.

I write that I wish to move beyond the book.

Beyond my life into another life.

I put the pen down.

The book says: ‘He put the pen down

and turned and watched her reading

the part about herself falling in love.’

The book is more accurate than we can imagine.

I lean back and watch you read

about the man across the street.23

The poem’s final stanza shows the couple abandoning themselves to a life that is inscribing itself – playing with the temporality of writing and sensation.

7. Yes, I want to keep reading.

I say yes to everything.

You cannot hear me.

“They sat beside each other on the couch.

They were the copies, the tired phantoms

of something they had been before.

The attitudes they took were jaded.

They stared into the book

and were horrified by their innocence,

their reluctance to give up.

They sat beside each other on the couch.

They were determined to accept the truth.

Whatever it was they would accept it.

The book would have to be written

and would have to be read.

They are the book and they are

nothing else.24

‘The Story of our Lives’ suggests the horror of a life that is all representation – a story told as it is lived. In 1971 American television audiences were gripped by the programme An American Family, in which a camera crew documented the lives of the Loud family. As the recording progressed the marriage at the centre of the family broke apart. It was difficult for the audience to pick apart in the recordings what was performance for the camera, performance learnt from watching television, and what was ‘real’ life. The fear that mediation makes mimics of us all, drawing out any sense of authentic affect, seems to be reflected in Strand’s final line: ‘They are the book and they are nothing else.’ The much vaunted liveness of video might be read in light of this; as much a dystopia as part of the futurist dream of its many cybernetic evangelists.

Although Benglis and Morris’s video collaboration can be said to be posited on a model in which ‘the self is created through the electronic device of feedback’, it is far distant from the narcissistic – its relationality is based on exchange between subjects rather than a solely self-reflecting circuit. It seems to be an investigation of what might happen if these mediated ‘selves’ – for Krauss mere ciphers of the machine – could somehow relate to one another. This is still a system that refuses ease of communication and the utopian vision for video art practice that was highly influential at the time of the tapes’ production. The journal Radical Software published a number of texts that explicitly related video technology to systems theory and cybernetics. William Kaizen has discussed the work of the artist Paul Ryan, who had studied with the visionary techno-utopianist Marshall McLuhan.25 In Ryan’s 1969 work Everyman’s Moebius Strip he demonstrated the way in which a closed circuit causes the observed subject to alter themselves in relation to feedback. In the work the artist’s voice lulled the viewer-participant into a relaxed state then asked them to react to a list of charged names (for example Huey Newton, mother) as they observed themselves. Beth Capper has recently written about the more playful experiments with self-observation carried out by Shirley Clarke as part of her game-like TeePee VideoSpace Troupe.26 As part of a workshop practice (which heavily influenced the video work of her daughter Wendy Clarke) participants would videotape themselves and then be taped while watching the footage back. While Michel Auder (in echoes of An American Family) videotaped his family life with his wife Viva in Chronicles: Family Diaries 1971–3, Viva’s second novel, The Baby: A Video Novel, based on the tapes suggests that they frequently shot footage of the family reacting to earlier tapes.27 These closed communication systems seemed for several pioneers of the video medium to signal the way in which communications technologies – if used in an ethical manner – could create self-balancing systems that would in turn make more self-aware citizens.

Fig.10

Robert Morris

Voice 1973–4

© Robert Morris

At the time he was working with Benglis, Morris was heavily influenced by the writing of the anti-psychiatrist R.D. Laing, whose work The Divided Self strongly questioned the language, if not the thinking, of cybernetics, in particular its reliance on understanding human subjects through mechanical metaphors.28 Laing encouraged his readers to understand psychotic symptoms as all too human affects. Art historian Maurice Berger has understood Morris’s exhibitions that were advertised with the storm trooper poster to be linked to the findings of anti-psychiatry.29 Rather than emphasising the potential for artworks to make better, more self-aware citizens, Morris at this point made work that seemed to mirror the dysfunctional society that he found himself surrounded by. The sound work Voice 1973–4 included citations from Emil Kraeplin’s writings on dementia and provided a polyphony of voices and sounds through eight audio tracks that were difficult for the listener to pull apart (fig.10). The Blind Time drawings (exhibited at Castelli-Sonnabend in SoHo at the same time as Voice) were made both by a blindfolded Morris and by a blind artist working under his instruction. Concurrently at the Institute of Contemporary Art in Philadelphia Morris showed Labyrinth, an eight-foot-high rendering in plywood and Masonite of the floor labyrinth at Chartres Cathedral, which encouraged viewers to become claustrophobic and disorientated (fig.11). Berger, thinking particularly of Herbert Marcuse, outlines that ‘the concept of autistic or psychotic states as recuperative experiences was central to those aspects of New Leftist thinking in the 1960s and 1970s that sought to disavow the standards of normalcy that govern late-industrial society’.30 To revel in the breakdown of rationality and meaning suggests for Berger ‘a transcendental, albeit desperate, search for recovery from the conditions of alienation that haunt us all’.31

Fig.11

Robert Morris

Labyrinth 1974

© Robert Morris

As Mumble progresses the sound element of the tape begins to break down into white noise and nonsense. Morris and Benglis are the pathology in the machine so feared by Krauss, if not quite in narcissistic mode, their work striving for the recovery from alienation through psychic disruption. Looked at in this way Morris and Benglis’s tapes may allow us a glimpse into the emergence of a form of subjectivity borne from technological mediation – an identification with images rather than individuals that characterises much communications technology today – but is also able to show its failures and fissures. Both of the videos are uncomfortable to watch – the images are grainy and deteriorate as they are copied through re-photographing, the audio is also difficult to follow as it often becomes engulfed (both accidentally and deliberately) in background noise. The narration becomes increasingly disjointed from the images and at times deliberately contradicts them. Even in the opening sequence of Mumble the flickering screen is already pitted against its soundtrack as Benglis announces the tape as an image of Morris while the viewer looks at the profile of her brother. Later in the tape Benglis makes reference to the sound of weaving, which cannot actually be heard and thus locates this noise off screen, an area invisible to her camera. In Exchange Morris’s text suggests there was no one weaving downstairs – only Benglis weaving her tapes through the spools of her equipment. This is a direct contradiction of the idea that what is seen in the feedback loop of video is a self-contained, self-observing world – both artists stand in relation to it at a remove, adding the soundtrack later as a critique to that moment of being lost in the liveness of its channels. Both videos suggest very firmly the existence of a private, unscreened, corporeal life and the value of maintaining it that way. This is a presentation of bodies far from the glossy pages of magazines like Artforum, these are images destroyed by their medium, shattered into pixels that refuse to cohere. While inviting their viewers to invent their own narratives from the stories they send out piecemeal, they refuse to map themselves onto real private lives. They are then half-empty avatars rather than people, allegories that might teach us to value our privacy and our fully corporeal selves anew.