The interwar decades were characterised by a fascination with the shifting geographies of artistic bohemianism and its popular reconfiguration within the changing conditions of post-First World War culture. In 1926 the British press claimed that the older tropes of bohemianism were finally dying out by stating that London has no Latin Quarter, a reference to the famous bohemian neighbourhood in Paris. An article in the Westminster Gazette in March that year titled ‘Artists Lost in London. New Ways of Modern Bohemia’ argued that the demise of vernacular forms of bohemianism was largely due to the spread of globalised travel, commercialised entertainments and the mass media.1 The article also blamed this situation upon the influx of foreigners into the metropolis, particularly from the United States, claiming that Americans had swamped the British out and that Americanised forms of living and entertainment had conquered the capital.

Taking up the topic in December 1926, the Illustrated London News cited recent changes in the commercial, moral and sexual codes of urban society, not as a consequence of the global economy or a pervasive Americanisation at work, but more as a result of greater sexual equality, seeing such trends as a natural continuation of pre-war transformations in which traditional and newer ways of life overlapped in the city.

The modern nightlife of London, like that of Paris and other capitals, is a growth of the twentieth century. The dance clubs with their cabaret shows and the similar entertainments provided in the great hotels are a fashionable development from the old ‘Bohemian’ habits of the past. The social tone is much higher and the setting more sumptuous and magnificent … The transformation of such resorts into recognised places of amusement is largely due, no doubt, to the emancipation of woman, who has won her right to share with man his frivolities as well as his professions.2

Accompanying the article were illustrations of ‘London Society’s Nocturnal Haunts’: the commercial sites for the consumption of this new more egalitarian and emancipated cosmopolitanism. At the top left was a sketch of ‘Dancing at the Fashionable Embassy Club’ in Old Bond Street to the British band-leader Bert Ambrose and his orchestra. At the bottom left there was a drawing showing an energetic tango routine at a themed Apache dance (gangster dance) at Ciro’s Club, which had international branches in Paris, Monte Carlo and Biarritz. In the centre, there was a sketch of the ‘Midnight Follies’ cabaret show at the Hotel Métropole on Northumberland Avenue. At the top right, there was a drawing depicting Nick Lucas, the popular American crooning troubadour, performing at the Kit-Kat Club, which was famous for being the most luxurious dance club in the world. Finally, at the bottom right, there was a drawing showing fashionably dressed, elegant couples dancing on the multi-coloured illuminated floor of the Florida Club in Bruton Mews in Mayfair. Evidently what had previously been in the pre-war years the signifiers of a racy avant-garde bohemianism – daring tango dances, rough criminal gangs, outcast subcultural types and vital American jazz – had already become well established in the mainstream. Commodified as spectacular entertainment, they were a regular feature in press coverage of the London social scene and were part of this newly reconfigured, globally consumed post-war entertainment culture clearly evident in London’s fashionable hotels and clubs.3 However, these passionate dances, sensational cabarets, racy music and underworld figures still carried the frisson of excitement that such imagined identifications represented as a way of shaping and configuring modern identities and testing society’s sexual and racial limits.4

From his days as a student at Chelsea Polytechnic from 1921–3 until the early 1930s, Edward Burra and his circle’s sense of themselves as ‘modern’ was shaped within and by these metropolitan spaces and by their sense of collective participation in a revitalised post-war nightlife.5 At Chelsea Polytechnic Burra encountered dancer and designer William Chappell, photographer Barbara Ker-Seymer and Clover Pritchard (later married as Clover de Pertinez). Burra and his friends used to meet at cafés and tearooms such as the Lyons Tea Houses, particularly the one on the corner of Oxford Street and Tottenham Court Road where, according to Ker-Seymer, they ‘used to sit … till about 4 o’clock in the morning’.6 They regularly attended the cinema and the ballet – the Ballets Russes in particular. ‘We were cinema mad and great ballet fans … we would queue for five hours for Ballet Russes tickets in the gallery’ remembered Ker-Seymer.7

At the Royal College from 1923–5, Burra made more artistic friends including Lucy Norton, Doris Langley Levy and Irene Hodgkins. Through Norton, Burra and Chappell met Frederick Ashton, who was then dancing with Marie Rambert.8 Through Ashton, Burra met the Polish painter and theatre designer Sophie Fedorovich and the society photographer Olivia Wyndham. These introductions were to provide Burra with access to many successful circles in the ballet, theatre, art, photography and journalism worlds, and to the smart young socialites and high bohemia of Chelsea and Bloomsbury. Moreover, these circles were comprised of many cultured gay and bisexual men: Chappell, Ashton, Neil ‘Bunnie’ Roger, the artists John Banting, Robert Medley, Cedric Morris and Arthur Lett-Haines, the dancer Rupert Doone, and the writer Brian Howard.9 There were also many bisexual women and lesbians. As Ashton remembered, throughout the 1920s ‘I used to be an escort to a host of lesbians’.10 These included Ker-Seymer, Wyndham, Ruth Baldwin, the journalist for Town & Country Marty Mann, the editor of British Vogue Dorothy Todd and her partner, journalist Madge Garland, and the Black-American actress Edna Lloyd Thomas.11 In spite of male homosexuality being illegal, such artistic and literary circles were fashionable and well-connected at home and abroad.12

Fig.1

Edward Burra

Jazz Fans 1928–9

Pen and ink on paper

4350 x 3700 mm

© Copyright care of Alex Reid and Lefevre London / courtesy of the Government Art Collection (UK)

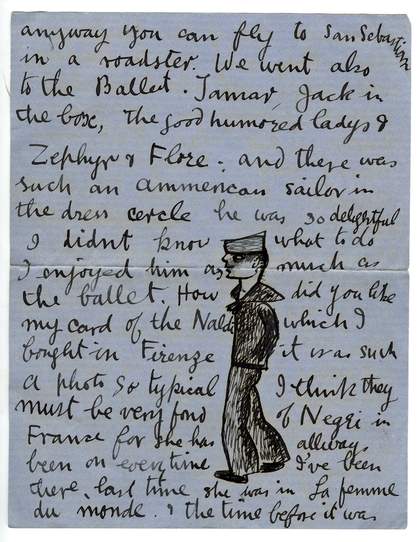

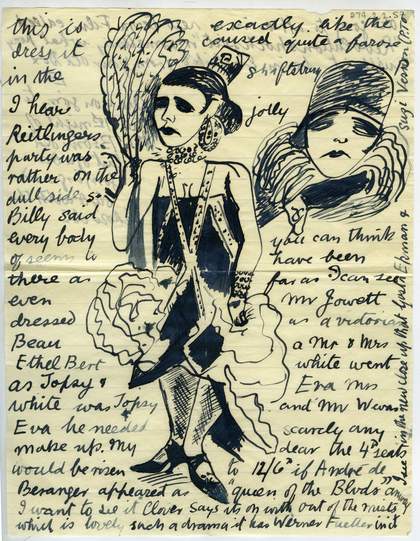

The drawing Jazz Fans 1928–9 (fig.1) signals Burra’s apparent active participation in London nightlife. The scene captures not only the informality of young friends at home enjoying the recent craze for jazz music, but also demonstrates Burra’s keen eye for the novelties of contemporary fashion. On the left, a woman with bobbed hair is depicted in a beaded dress smoking while she changes the record. The other women – with their slender, boyish silhouettes, shorter hemlines, fashionable footwear and contemporary make up comprising dark eye shadow, pronounced rouge and bold lipstick – show Burra’s attention to the conspicuous modernity of their looks. Undoubtedly he did go to some parties such as with Ker-Seymer to Cedric Morris’s and Arthur Lett-Haines’s party at their flat on Great Ormond Street in May 1928, also attended by Virginia Woolf, Vanessa Bell and other members of the Bloomsbury circles.13 However, Burra was not a party animal, partly due to his variable ill-health and partly because he lived most of his life in the Burra family home at Springfield Lodge in Rye.14 To get a sense of his detachment from the scene and his voyeuristic delight in watching from a distance, Burra’s letters are revealing. They reconstituted afterwards the gossipy stories, sexual tittle-tattle and exaggerated recollections of his friends, which were then transcribed by Burra into his saucy, illustrated letters to other friends where he slid between reported first-hand experience and second-hand contrivance. In a letter he wrote to Ker-Seymer on 23 July 1926 describing his evening at the Ballets Russes, Burra drew a ‘delightful’ American sailor seated in the dress circle who had attracted his attention and who ‘he enjoyed as much as the ballet’ (fig.2). In another letter dated 2 June 1928 (fig.3), Burra wrote to Ker-Seymer about the art writer Gerald Reitlinger’s celebrated sailor themed party:

Fig.2

Edward Burra

Letter to Barbara Ker-Seymer 23 July 1926

Letter TGA 974/2/2/8

© Ker-Seymer

Fig.3

Edward Burra

Letter to Barbara Ker-Seymer 2 June 1928

Letter TGA 974/2/2/57

© Ker-Seymer

Did B[illy] tell you of the matelot [sailor] party empress L[ucy Norton] took him to? Did I say matelot party? Matelots is not what I have heard it called. Oh dear no. my dear I read all about it in the Weekly Dispatch. everyone attacked everyone else and mounds of young men writhed in heaps in every corner.15

The letter incorporates a drawing of the Austrian actress Ellen Richter’s ‘chic evening gown’ in a film he had seen her in that evening and which ‘caused a furore in the Shaftesbury [Pavilion cinema]’. Burra’s reframing of events was keenly informed and shaped by contemporary journalism and film culture and expressed not least without some sense of irony and camp. As the popular and illustrated press expanded, and with silent film offering the potential of an internationally syndicated, universal visual language, the styles and techniques of the modern mass media transformed the ways in which the metropolitan environment was approached and understood. As de Pertinez recalled, Burra’s circle avidly read Vogue alongside other glossy mass-market magazines such as Vanity Fair and Harper’s Bazaar and they ‘aspired to the smooth chic and sophistication to be seen on the covers of Vogue by Erté and Georges Lepape’.16 These magazines covered a wide range of current intellectual and critical developments, recasting complex and sophisticated ideas from modernist literature, philosophy and the visual arts into more accessible prose, thereby introducing to a younger readership difficult works from the avant-garde. Cultural theorist Michael Murphy has argued that by making ‘popular forms … intellectually fashionable’, Vogue promoted a sense of being up-to-date and in-the-know, offering ‘a peculiar combination of elitism and commonality … [which] became synonymous with modernism for many of its readers’.17

Cultural historian Christopher Reed has demonstrated how British Vogue was transformed under Dorothy Todd’s editorship from 1922–6 from a conventional fashion magazine whose staple elements were high society, the rich and famous, and haute couture, into a dazzling review for avant-garde writers that engaged with ‘broad issues of gender, sexuality, class and mass culture, and the relationship of all of these to definitions of modernity in the 1920s’.18 Todd, and her partner Madge Garland, as already mentioned, were friends of Ashton, Ker-Seymer and Fedorovich, and they held wild parties at their Chelsea studio. Moreover, as Reed has emphasised, Todd’s editorship of Vogue and the subcultural sensibility it publicised offered ‘a vision of modernity defined not only by trends in hemlines, but by new claims for women as both consumers and producers of avant-garde culture’.19 What is clear is that these magazines inscribed on to the earlier formats of social scene reportage, society pages and travelogues, contemporary understandings of them as metaphors for an updated and sophisticated modernity also evidenced in contemporary popular fiction, fashion, entertainment, dance, jazz music, photography and film.

Film culture was particularly influential, as Kenneth Macpherson in the February 1928 issue of the film journal Close Up declared: ‘the cinema has entered into the modern consciousness (and by modern consciousness I mean the consciousness of the younger generation)’.20 Some contemporary writers even claimed that ‘the modern mind has become a cinema mind’.21 The 1920s was the decade in which film was starting to be treated seriously and when newspapers and magazines regularly published film reviews, criticism and listings accompanied by stills illustrating the films.22 The launching of the London Film Society in October 1925 reinforced this viewpoint and Burra and Ker-Seymer were Film Society-goers from the start with their diaries and letters signalling their regular attendance as well as their interest.23 At this time, as Ker-Seymer recalled ‘we saw a lot of German silent films, some at the [London] Film Society … We were passionately interested in everything German – the films and the photobooks’.24 De Pertinez similarly remembered that ‘we shared a passion for German silent films made by UFA and travelled … to the suburban cinemas which in those days to their credit showed the Cabinet of Dr Caligari, The Blue Angel, Mädchen in Uniform, Metropolis and a lot of lesser German pictures’.25 Burra was also fascinated by Russian film, an interest reinforced by his purchase of Berlin-based drama critic Alfred Kerr’s Russische Filmkunst (1927) and by articles in Close Up.26 In August 1928, Burra declared ‘I can’t miss anything continental even if I have to see every Battleship in Europe scuttled’ (a reference to Sergei Eisenstein’s 1926 film Battleship Potemkin, which he saw at the London Film Society).27

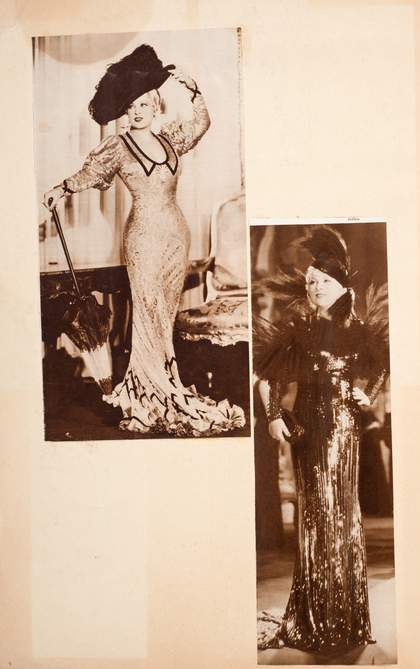

Fig.4

Photographs of the actress Mae West in Edward Burra’s scrapbook c.1929–36

Scrapbook TGA 939/8/1 no.5

© Edward Burra

However, Burra’s taste was not purely for ‘ultra-modern’ avant-garde films from Germany and Soviet Russia, nor did he read only the more specialist journals that championed international film art such as Close Up from 1927.28 Rather he adored popular film journals, fanzines and scandal sheets such as the British magazines The Bioscope, The Picturegoer, Picture Show and Film Weekly, and the American publications Photoplay, Motion Picture Magazine and Movie Weekly, which apart from containing illustrations, advertisements, photographs of actors and actresses on set and film stills had ‘uncensored’ interviews and ‘off the record’ disclosures about Hollywood stars, their careers and their private lives.29 Burra pasted cuttings with images from these and other sources into large scrapbooks for reference (fig.4).30

One aspect of this novel, media-informed approach was that it privileged the use of ironic contrast in which sudden transitions between the high and the low, the comic and the bathetic, the artistic and the commercially orientated undermined seriousness and checked pretensions. It was just such a deflationary strategy involving gossipy innuendo, unsubstantiated rumour, shared hidden meanings, camp humour and piercing irony that Burra marshalled effectively throughout his life, and infused into his letters and his work. As Burra put it in a letter to Ker-Seymer in October 1927, ‘I’m sorry I’m not as good as the Tatler but London Life + the World’s Pictorial News flavoured with the Police Gazette is more my line old tart’.31

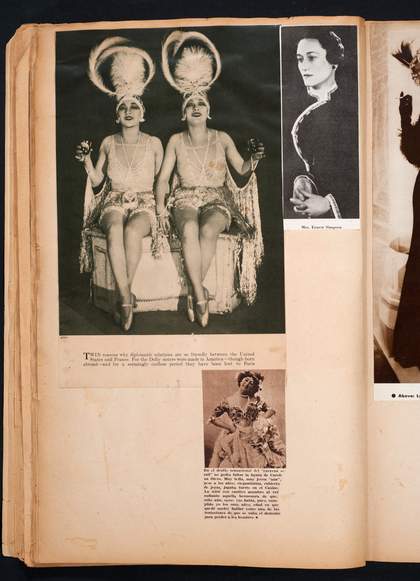

Fig.5

Photographs of the Dolly Sisters in Edward Burra’s scrapbook c.1929–36

Scrapbook TGA 939/8/1 no.6

© Edward Burra

Burra’s paintings developed what Christopher Reed has called ‘a now forgotten style called “amusing”’, which was promoted by the writers Edith, Osbert and Sacheverell Sitwell in the late 1920s and adapted by Bloomsbury artists in which there was an ‘amusing ideal’ of blending historical references with newer, avant-garde interests and aesthetics.32 According to Osbert Sitwell, the ‘Amusing style’s’ transgressive nature was described as epitomising a ‘“modern” sensibility … one that made new meanings from old modes’ and it derived its pleasure in making knowing quotations and sophisticated allusions by deploying pastiche and adopting a humorous ‘camp’ tone as a mode of being conspicuously modern.33 For example, Burra’s The Two Sisters 1929 aligns with this approach, depicting within a French Mediterranean setting two sisters modelled on the Hungarian-born, twin-sister dancing act the Dolly Sisters (fig.5). The painting updates eighteenth-century conversation pieces by William Hogarth (such as The Strode Family c.1738, Tate N01153) and employs a neo-classicism that recalls the work of Gino Severini (for example Three Commedia dell’Arte Musicians 1922), but also Fernand Léger, whose work Burra saw illustrated in Vogue in October 1925 in an article that included the works Animated Landscape 1924–5 (also known as Les Visiteurs) and The Mechanic 1920.34 The formality of the art-historical referencing and the culture of civilised politeness associated with the Hogarthian conversation piece is undermined by the Dolly Sisters’ suggestive low-cut dresses and their flaunting of breasts and nipples. For those Hollywood watchers in the know, like Burra, the ‘Heavenly Twins’ as the Dolly Sisters were popularly known, had a reputation as gold diggers for attracting and then allegedly fleecing older millionaire admirers to bankroll their extravagant lifestyles and gambling addiction.35

The passionate commitment of Burra’s social circle to developing an updated cosmopolitan modernism was impressive. It was historically informed yet shaped by popular illustrated magazines devoted to dance, music and film; it gloried in the shared informal experience of metropolitan life, its high-low, cross cultural and transatlantic complexions; and it embraced foreign travel and accelerating global mobility. Moreover, when located in the music halls and bals-musettes in Paris, in the sailors’ bars and cafés of Marseilles and Toulon, and in the cabarets, dance halls and jazz clubs of Harlem, it was an outlook which promoted more relaxed, contemporary roles for young men and women by championing sexually liberal values and accepting homosexuality.

Paris

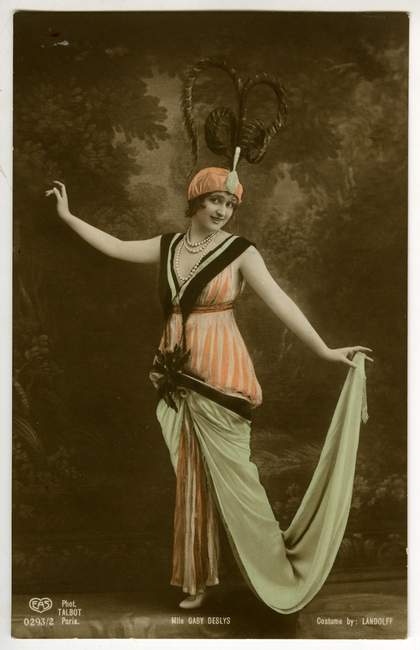

Fig.6

Photograph of the singer Gaby Deslys in Edward’s Burra’s scrapbook c.1929–36

TGA939/8/1 no.6

© Edward Burra

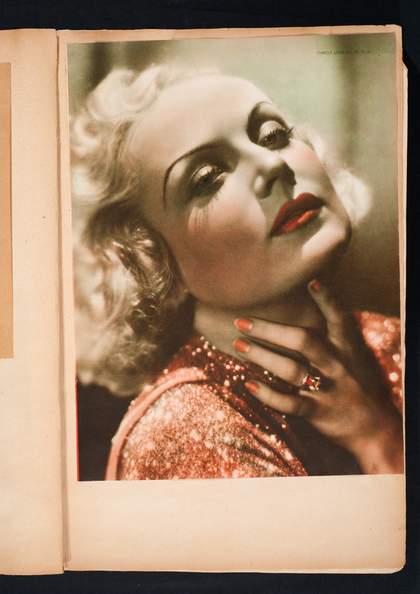

Fig.7

Photograph of the actress Carole Lombard in Edward Burra’s scrapbook c.1929–36

Scrapbook TGA 939/8/1 no.7

© Edward Burra

During the 1920s Paris became one of the most powerful metaphors for a European urban experience centred on luxurious consumption and sophisticated lifestyles.36 Within its haute couture fashion houses, its fine restaurants and bars, and its burgeoning entertainment industries, Paris was what writer Sisley Huddleston in Bohemian, Literary and Social Life in Paris (1928) termed ‘a vivid journalistic city with whose ways we are so familiar’.37 One reason for this was the way the popular press exemplified by Le Détective, VU and Le Crapouillot provided new ways of seeing and dramatising urban life by sensationalising the everyday. Another was the influence of films of Paris life that refigured the city, its sights and its neighbourhoods within spectacular modes produced for international consumption. 38 Throughout the 1920s, not only French filmmakers but also German and American directors exploited the connotations of sophisticated modernity which Paris held for an expanding number of younger, especially female movie-goers.39 This fascination with the city extended to those international celebrities participating in the Paris ‘High Society’ season such as Mistinguett, Josephine Baker, the Dolly Sisters, Harry Pilcer, Gaby Deslys (fig.6), Lily Damita, Errol Flynn, Carole Lombard (fig.7), Marlene Dietrich and many more; stars whose images Burra collected in his scrapbooks. Vogue regularly promoted the notion of Paris as synonymous with an elegant sophistication. It was a message not lost on Burra, who wrote from Paris in October 1928 that ‘the people are so glorious, so chic’40 and who could recognise the French designer styles as many were ‘dressed by [Jeanne] Lanvin’.41

Burra was intermittently resident in Paris between 1925 and 1933. He had learnt French from the age of eight so that by the time of his first visit to the French capital in October 1925 Burra had a full command of the language, reading widely, learning song lyrics by heart and employing colourful slang terms. The sights and nightlife of Montmartre and Montparnasse featured extensively in his work. With Ashton and Chappell in Paris from 1928–9 working for the Ida Rubinstein ballet company, and Fedorovitch there painting ballet sets for the Ballets Russes and ‘in with all the Diaghilev lot’, Burra thrived in these expatriate circles.42 His letters home glory in the endless cycle of bars, cafés, cinemas, music halls, ballets and revues. What distinguished Paris in his eyes was its liberal culture and permissive sexual manners in which gender roles were fluid and sexual protocols relaxed. Burra noted how the vibrant world of Parisian street life could only be understood as a dazzling kaleidoscopic array where ‘real’ life intersected with media reports, celebrity identifications and film in a thoroughly modern, montaged way. In a letter to Ker-Seymer dated 9 October 1928, Burra included references to the recently released German films La Grande Aventurière (by Robert Wiene, 1927) starring Lilli Damita, to G.W. Pabst’s films The Love of Jeanne Ney (1926) and Crise (1928), to Vogue illustrations by André Lepape, and to the pleasures of Parisian shopping. He wrote that the hotel in which he was staying in Montparnasse

is exactly like the hotel in the Loves of Jeanne Ney … We went to a glorious film today featuring Lilli Damita, Georg Alexander and Alphonse Freidland. Such luxury has never been seen. I didn’t think Lilli D could possibly be so chic. La Grande Adventurière it was called … Lilli D looks just like a continuous succession of Vogue drawings, covers of Harper’s Bazaar, Vanity Fare [sic] and drawings by André Lepape.43

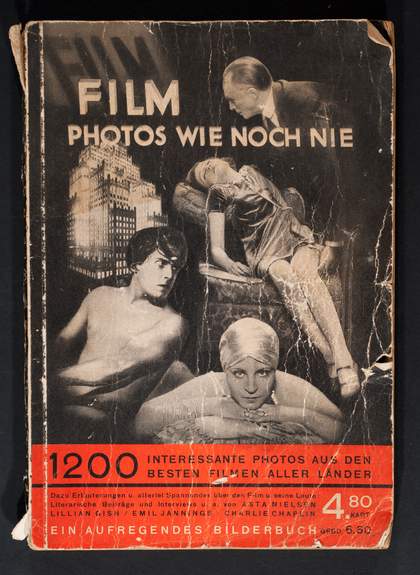

Fig.8

Front cover of Film. Photos Wie Noch Nie (1929)

© Edward Burra

TGA

The following day Burra wrote again ‘Crise the new Pabst film is starting here on Friday for a Grand run featuring Brigitte Helm and Jack Trevor. I must go. The photos look glorious’.44 Having been to the Café du Dôme, which Burra called ‘by all odds the most interesting place in all Paris’,45 he wrote ‘Have you ever seen anything so lovely as the Bazaar Hotel de Ville. Its my ideal shop. Also the Samaritaine isn’t too bad either’.46 It was in these Parisian inner-city commercial geographies and within these overlapping French and expatriate communities, mixing art, theatre and ballet worlds that an emancipated cosmopolitanism thrived. Burra’s scenes of Parisian nightlife depicted fashionable bars such as Le Boeuf sur la Toit 1930, which Burra visited in May 1929 and had red leather banquettes, parchment balloons and crystal orbs that festooned the chandeliers as well as a glamorous mirrored bar.47 His works also represent the racy burlesque shows of Belleville such as Les Folies de Belleville 1928 and the dancing troupes of the Follies and the Palace Music Hall – for example, Showgirls 1929 – entertainments that Burra went to so often that he started to recognise the dancers in the street afterwards, as he told Ker-Seymer.48

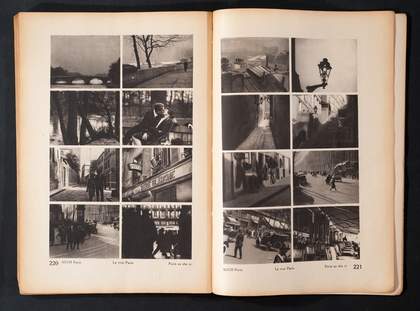

One feature of inter-war Paris was the way that photojournalism and film held an authority over how the city was understood and directed the ways in which previously localised meanings and cultural codings were reloaded with cosmopolitan associations and marketed globally.49 Burra bought film photobooks such as Film. Photos Wie Noch Nie (1929; figs.8 and 9) that contained film stills from Parisian themed films and he amassed an extensive collection of film magazines including Cinéa-Ciné Pour Tous and Cinéville.50 As a terrain of masculine social and sexual freedoms, Paris sanctioned modern configurations of homosociality and generated updated racy human interest stories, especially involving the underworld and prostitution. Burra’s focus was on the bals musettes, the popular dance halls of the city, in particular those on the rue de Lappe near Les Halles as in the drawings Rue de Lappe 1928 and Bal musette c.1928, and the painting Le Bal 1928.

Fig.9

Film stills in Film. Photos Wie Noch Nie (1929) pp.220–1

TGA

Although once celebrated as clandestine spaces for encountering criminal types, Apache gangsters, prostitutes, drug dealers and cruising for rough trade, the bals musettes and bals mixtes of the rue de Lappe were already well documented. Photographs by the Parisian Séeberger brothers captured the neighbourhood’s run-down streets, snapping the exteriors and interiors of the bals musettes: the Bal Monteil at 21 rue de Lappe and the dance hall Au Petit Balcon.51 They featured in popular French illustrated journals, notably Détective, Voilà, VU and Variétés – all collected by Burra – where photographs by Germaine Krull, Eli Lotar, André Kertész and Brassaï were employed as part of an innovative montage layout on ‘Montmartre nights’ or ‘Venal Paris’, or within racy photo-narratives that went ‘behind-the-scenes’ of the Paris underworld. 52 In April 1931 Détective featured just such a story with a cover photograph by Krull as part of an exposé called ‘La rafle au musette’ (police raid on the popular dance-hall). It was about how the Parisian police force had attempted to clean up the most notorious dance halls of northern and eastern Paris. Showing the packed dance hall inhabited by Apache gangsters wearing their distinctive caps with heavily made-up prostitutes and on-leave French sailors in uniform, the caption identified the precise location: ‘Rue de Lappe … the accordion sobs … the gangsters are diverted by the rhythms of the java or planning the next night’s attack … Outside the vans of the Paris police headquarters discharge an army of detectives, it’s a police raid’.53

While the bals held the vicarious excitements of going slumming, these marginal spaces also fostered diverse forms of heterosexual and homosexual cultures. As Daniel Guérin recalled: ‘These night clubs [in the rue de Lappe] were sexual, not homosexual, but in them there was enormous permissiveness – people didn’t kiss though, as the ‘lads’ stuck to their virile image’.54 Central to their attraction was dancing, especially the tango and the java. Burra first visited the rue de Lappe in March 1927 when ‘there was quite a little fricassee at the Bal. arrested for indecency indeed. did you ever?’ 55 On 9 October 1928 Burra reported again that ‘we penetrated about 40 miles into old Montmartre (the heart of the Apache quarter, you know)’.56 A few days later Burra was back at the dance halls on the rue de Lappe with Ashton, Chappell and Fedorovitch reporting to Ker-Seymer on events and noting that everyone in the dance hall addressed Fedorovitch as ‘monsieur’:

We went to the Rue de Lappe on Sunday. Me and Billy [Chappell] danced a beautiful tango. My dear you should have seen it. A dreadful creature in a dainty felt [hat] and pince nez tore off my jersey and as for Freddie [Ashton] he was surrounded by doubtful Spaniards who terrified him into paying for all their drinks. They also took all Sophie’s cigarettes when she was doing a cancan with Billy. Everybody pretended to think she was a man dressed up and kept saying ‘ah monsieur, monsieur’. As for the matelots such buttocks ma chere and the lesbiennes so long drawn out.57

This account was corroborated by Chappell who similarly reported that he had

danced with one of the Spaniards who made Freddie buy drinks. He had awful breath but was quite a twee of course. The one I should have liked would not dance. The great thrill of the evening was to see Ed [Burra] and me doing a voluptuous tango … The loveliest thing about the dancings in the Rue de Lappe is that one sees the toughest creatures in check caps and mufflers with heavy painted faces dancing together.58

From the evidence of these letters, indecency and crime, hot-blooded Latin types, passionate dancing, pronounced make-up and open displays of bisexuality and homosexuality mark out the seductive culture of the dance hall in terms of the visibility of its social range, its racial diversity and sexual difference. As an escape from the restraints of bourgeois English respectability, it was this interior space, its layout, décor and lighting, the sounds of the band, the unrestrained java and tango dances, and the bustling energy that stirred the imaginative potential for sexual adventure. And it was the visual details of these locations and characters that Burra’s Le Bal captured as an ‘authentic’ Parisian dance hall interior and crowd with a rich density of possible meanings that did not require translation for a London audience already familiar with its popular cultural signifiers: its dress, music, and dances.

Marseilles and Toulon

This fascination with low-life themes continued when Burra travelled to Marseilles and Toulon, first in September 1927 with Chappell, then a year later with Chappell, Ker-Seymer and Hogkins among others, then again in February 1930 with the Nashes and again in February and May 1931, and in autumn 1933. Usually Burra and his friends would stay in cheap hotels close to the ports in Marseilles and Toulon, the home of the French Mediterranean fleet. They would also shop for sailor wear, linen trousers and pom-pom berets to look the part, and they frequented the sailors’ bars and cafés, which became the subjects for works such as Dockside Café, Marseilles 1929 and The Waiter 1930–1.59 When works on Mediterranean subjects were exhibited at his first solo show at the Leicester Galleries, London, in April 1929, these associations were not lost on the critic R.H. Wilenski who noted that Burra had ‘been recently to Marseilles and succumbed with the enthusiasm of youth to the sordid glamour of the Marseilles underworld with its strange conglomeration of racial types and its thousand facets of Mediterranean life’.60

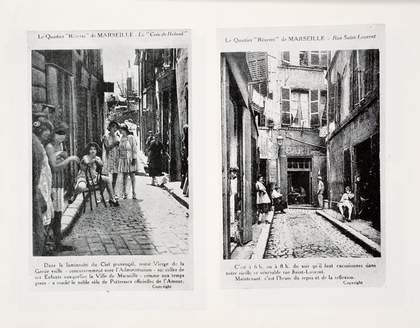

In June 1932, the Weekend Review critic detected similarities between Burra’s paintings and the work of Edward Wadsworth, whom Burra had met through Paul Nash the previous year.61 Wadsworth’s work depicted sailors’ cafés such as St Tropez 1925 and Bar de Marquis, Marseilles 1925, and it captured the narrow alleys with brothels in Marseilles such as Rue de la Reynarde, Marseilles 1925, Rue Fontaine de Caylus, Marseilles 1924 and Rue de Gassins, Marseilles 1924.62 Wadsworth’s works, like Burra’s Nitpickers 1932 show the dockside red-light area and prostitutes outside brothels. Burra was fascinated by the portside sex trade, writing that ‘The guide book says it is a veritable ghetto of houses of ill-fame. my dear I stares into every window hoping for a thrill’.63 Ker-Seymer recalled that on their visit in 1931 they had hoped to photograph the streets, brothels and the prostitutes at work but they got scared off:

Ed and I went up to the red light district in Marseilles where the elderly (to us) tarts sat on wooden chairs outside their bedrooms which opened onto the street concealed by bead curtains. We were going to photograph them, but one of them saw us and rushed after us calling out in French, ‘You’ll have to pay for that’, but Ed and I flew down a side street and escaped.64

Fig.10

Photographs of prostitutes in Varietés, 15 May 1929

Ker-Seymer recalled that ‘Not long after that we saw photographs in [the Belgian periodical] Variétés of exactly what we had seen’ (fig.10). 65

Wadsworth’s images focus on the streets with their wrought-iron brothel signs. However these paintings do not only document the sex trade in a detached way. Rather, they employ signs for prostitution as semiotic markers of and for the male tourist experience.66 From the evidence of Burra’s Dockside Café, Marseilles 1929, his motivation was somewhat different. The work portrays the harbour-side café culture and makes references to French popular fiction, songs and films in which portside cruising and sexual adventures were commonplace narrative devices in popular novels by Pierre Berard, Francis Carco and Pierre MacOrlan, all of which were read by Burra. Throughout the decade, racy stories about Marseilles’ quartier réservé and Toulon’s port-streets were also well known and commercially exploited by French illustrated magazines such as Vu and Détective, which produced ‘reveal all’ exposés of their seedy geographies.67

However, the main focus for Burra was undoubtedly the French sailor, his milieu and manners as can be seen in drawings such as Sailors at a Market 1930 and Sailors near the Grand Hotel c.1930, and paintings such as Rossi 1930 and Three Sailors at a Bar 1930. As cultural critic Adrian Rifkin has argued, the sailor had long been invested with potent erotic meanings as an exemplar of ‘virile masculinity’ within the burgeoning French mass media and on picture postcards which encouraged fantasies of portside adventure, sexual promiscuity and military exoticism such as Germaine Krull’s photograph reproduced in Variétés and Vu.68 For many English audiences this fascination with sailors carried suspicions of low-life cruising and an over-fondness for sexual slumming, even homosexual promiscuity, which heightened their fascination for Burra’s circles. The cult status of the sailor among celebrity homosexual circles in France such as those around Jean Cocteau, who Burra encountered in Toulon in August 1931 and who was photographed by Ker-Seymer in Toulon, and the fashion for the tight-fitting uniform among lesbian and gay men presented the sailor as a conspicuous and stylish icon of homosexual desire, and as a subject fit for a wild fancy-dress party such as the one at Gerald Reitlinger’s.69

Rossi exploits these potent mythologies of the French sailor and the Mediterranean port. In its use of dramatic close ups, an odd point of view and a decentred composition, it mobilised the sophisticated visual rhetoric and compelling ‘photo-eye’ of German ‘New Vision’ photography that offered a revolutionary way of seeing as extended by the camera’s eye.70 Paul Nash’s July 1932 article on ‘Photography and Modern Art’ in the Listener recognised this correlation and pointed to Burra’s painting The Ham 1931 as owing ‘something to [the] keen appreciation of the aesthetics of modern photography’.71 In this context Burra’s collection of German photography books and journals shaped and informed his pictorial practice. Ker-Seymer remembered that ‘We were passionately interested in everything German – the films and the photobooks. We also had [the German illustrated magazine] Der Querschnitt and, even though we couldn’t read German, this really was no problem’.72 Burra and Ker-Seymer ‘used to go to Zwemmer’s in the Charing Cross Road which had all the best art books and magazines’ on contemporary photography including the Fototek book Painting, Photography, Film (1927) by Lazlo Moholy-Nagy, and Franz Roh’s and Jan Tschichold’s photo-eye (1929) containing photographs such as Max Burchartz’s Lotte (eye) 1928 and Hans Finsler’s Incandescent Lamp 1929.73

The art historian David Mellor has identified how Burra’s interests corresponded with the breakthrough of German and Russian film and new German photography in London between 1929–32, marking Burra and Ker-Seymer alongside Nash, Wadsworth and others as converts to German ‘New Objectivity’ photography.74 For Burra, the photographers Germaine Krull and Florence Henri were especially influential.75 By September 1931 Burra and Ker-Seymer had become adept ‘at using German “Baby Box” cameras costing 12/6d’,76 and they were copying Krull’s style taking ‘negatives by the Germaine Krull method’ in Marseilles and Toulon, which were tiny but always in focus.77 Krull’s photo-studies of Paris and Marseilles were widely reproduced in the illustrated press and in photography magazines, notably Der Querschnitt, VU and Variétés, and available as published collections including Metal (1927), 100x Paris (1929), Krull (1931) by Pierre MacOrlan, and Marseilles (1935).78

Burra’s painting Rossi demonstrates the application of Krull’s approach. It presents a portside café with the berets on the hat stand signalling it as a popular locale for sailors and their associates. By implication, it suggests an identification with the sailors’ famed homosociality as the scene is approached from the viewpoint of a fellow diner seated across from a table where two sailors, one seen in sharp profile and another pouring wine and partially hidden, are sitting. The foreground is dominated by the looming presence of the Rossi bottle with its lecherous face brand label. This angle repeats a frequently used photo-reportage technique of taking a snapshot by raising a previously concealed camera above the level of the table and quickly snapping the scene as in Krull’s Au Caboulet, Paris 1928, where she probably employed a folding camera.

Moreover, the sailors’ bodies and musculature, the surfaces of the napkin and bottle, the details of the Rossi label, the elaborate wallpaper pattern and the ornate lamp stand and lampshades all remain sharply in focus. The deployment of the close up to disturb routine formal and spatial conventions in Rossi was a feature widely associated with ‘New Objectivity’ practices and with the dissemination and incorporation of radical Bauhaus aesthetics in contemporary advertising photography. In this respect, for example, Florence Henri’s 1929 La Lune Coquillettes advertisement for pasta similarly features a humorous grinning moon reminiscent of the Rossi label and it shows how German photographic methods were being adopted and circulated by and through the commercial channels of the advertising agencies.79

Three Sailors at a Bar 1930 is instructive in many ways about Burra’s fascination with the French sailor and how it was informed by the work of Henri, whose photographs married abstraction with advertising indicating that she had absorbed the lessons of international constructivism. One of Henri’s photographic ploys was to use plate-glass shop window reflections to manipulate space and form, thereby creating a pictorial ambiguity that set up a dialogue between the inside and the outside. This strategy produced an idiosyncratic view of city life as her Window Compositions 1929–30 and Vitrine works from 1930 signal.80 Burra and Ker-Seymer adopted this method and they took photos of shop windows replicating her approach. They also copied the earlier shop-front photographs of the French photographer Eugène Atget, such as Corsets, Boulevard de Strasbourg, Paris c.1900, which was reproduced in Roh’s and Tschichold’s photo-eye and referred to as ‘photographing à la Atget’.81

Another means used by Henri to make appearances appear afresh and to gain structural clarity was to dislocate perspective within the confines of a restricted space. The incorporation of mirrors and the use of mirror reflections was deployed to achieve this effect, as in her portrait compositions such as Man Looking in Mirror Holding Ladder 1928, her still life compositions, for example Mirrors, Ball and Grate 1928, and the later advertising photographs such as Columbia Records 1931 and Au Bon Marché 1931.82 Burra’s Three Sailors at a Bar is a similar exercise in disrupting the nature of visual appearances as the interior of the bar is reflected through a mirror whose frame is shown on three sides of the work. Shown in another mirror opposite, the sailors become embroiled within a labyrinth of reflected images and deflected spatial alignments rather like a complex hall of mirrors through which the real and the reflected are ingeniously confused. Nevertheless, as the spaces of the bar become dislocated and ambiguous there is no loss of architectural clarity or optical precision. Signalling Burra’s fascination with the sailors, their bodies and uniforms are presented clearly in focus and open to careful scrutiny. As such, Burra’s approach to representing the sailors cafés and dockside bars in Marseilles and Toulon was clearly indebted to the methods and techniques of ‘New Objectivity’ photographers, Krull and Henri in particular, whose visions of the city offered a vivid immediacy and fresh ways of reconceiving the everyday. Their innovative approach to photographing the contemporary world was highly suited to Burra’s desire to explore new ways of seeing, understanding and representing modern identities and social manners.

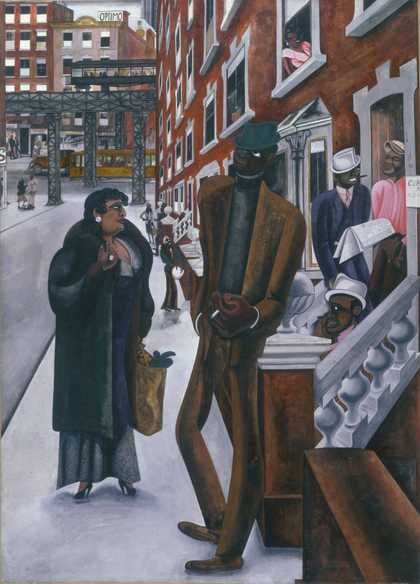

Harlem

Burra’s fascination with the vibrant street life of large cities continued in New York whose distinctive elevated railways, rows of brownstone houses and multicultural communities of the rapidly growing and racially mixed inner-city neighbourhoods of Harlem and Spanish Harlem became the focus of the artist’s works. Completed in 1934–5, the three street scenes Harlem 1934 (fig.11), Harlem 1934 (Cecil Higgins Art Gallery, Bedford) and Harlem Scene 1934–5 derive from Burra’s trip to the United States between October 1933 and March 1934, when the artist stayed initially at 1890 Seventh Avenue in Harlem with Olivia Wyndham and her lover, the well-known African-American actress and celebrity Edna Lloyd Thomas.83 Lloyd Thomas was pioneering the revival of black theatre at the Lafayette Theatre in Harlem and she would star as Lady Macbeth in Orson Welles’s famous all-black cast production of Macbeth in 1936.84 ‘Olivia’, wrote Burra, ‘is such a figure in Harlem society you cant [sic] conceive. She seems to know all the neighbourhood.’85 Her friends included the black heiress and Harlem Renaissance patroness A’Lelia Walker and the actor Paul Robeson as well as many members of the Harlem intelligentsia.86

From the end of 1933 Fedorovich and Ashton were also in New York, with Ashton working as a choreographer on Virgil Thompson’s all-black production of Gertrude Stein’s opera Four Saints in Three Acts.87 The opera opened to rave reviews in February 1934 in Hartford, Connecticut, with sets designed by Florine Stettheimer, and transferred to Broadway later that year.88 In Manhattan, Ashton was staying on East 61st Street with Kirk and Constance Askew, Kirk being the director of the 57th Street branch of the Durlacher Brothers Art Galleries. The Askews held regular Sunday afternoon ‘at homes’ that Burra and his friends attended, and which attracted an influential New York artistic circle. ‘Theres [sic] so much talent at the partys here’ Burra reported to Chappell back in England.89 Visitors included the Director of the Museum of Modern Art, Alfred Barr, the architect Philip Johnson, musicians Aaron Copland and Leonard Bernstein, the critic Lincoln Kirstein, photographers George Platt Lynes, George Hoynigen-Huhne and Lee Miller, as well as the painters Pavel Tchelitchew and Florine Stettheimer.90

In his Harlem street scenes, Burra accentuates the urbane manner and sartorial creativity of African-American and Hispanic-American styles. Trends in fashion such as the polo-neck sweater, the flat cap, the fedora hat, the trench coat and the racoon coat are carefully documented. Details of hairstyles, expressions and gestures are keenly noted as key signifiers of that communal vibrancy enthusiastically promoted by Harlem intellectuals and fostered by its creative institutions.91 Celebrating such multi-racial diversity, Burra’s approach aligns with the interest in African-American culture signalled in writer Nancy Cunard’s anthology Negro, published in 1934.92

In terms of nightlife, drawings such as Dance Hall, Harlem Night Club 1934 and paintings such as Savoy Ballroom, Harlem 1934 and Savoy Ballroom, Harlem 1934–5 capture Burra’s fascination with Black-American dancing. ‘We went to the Savoy dance Hall the other night you would go mad. Ive [sic] never in my life seen such a display an enormous floor half dark surrounded by chairs & tables and promenade on one side and the band on the other with a trailing cloud effect behind. Ive [sic] never seen such wonderful dancing’ Burra reported to Ker-Seymer.93 In January 1934, Burra moved to125 East 15th Street on the Lower East Side and in his inimitable helter-skelter prose the artist again recorded the excitement of nightlife in Greenwich Village and Harlem:

We visited a few hot spots one in the village which was camp lovely my dear … then we went to the Savoy and then to Hot Cha … where a shame making man sat down at the table and burst into La Paloma … then we went to an underground graveyard called the log cabin my favorite resort.94

On other occasions, Wyndham and Lloyd Thomas took Burra to the Clam House on 133rd Street where openly lesbian Gladys Bentley performed, and to her Mona’s Club 440 lesbian bar. They also went to the Theatrical Grill, where Burra encountered Harlem’s best known drag queen Gloria Swanson. He reported home to Chappell:

We went to an outrageous place called the theatrical grill. A cellar done up to look like Napoleon’s tomb and lit in such a way that all the white people look like corpses. Ive [sic] never seen such faces, the best gangster films are far outdone by the old original thing. The chief [attraction] of the cabaret was Gloria Swanson, a mountainous coal black [man] in a crepe de chine dress trimmed [with] sequins.95

As shown on a 1932 map of nightclubs in Harlem by E. Simms Campbell, the area was at the centre of a booming interest in and engagement with Black-American music and entertainment culture.96 As the journal Variety boasted, there were over eleven class white trade nightclubs and over five hundred ‘cabarets of lower ranks’ in Harlem.97 As the map declares in the centre-left scroll, there were even too many dives and speakeasies to record accurately: ‘In this section of Harlem there are clubs opening and closing all the time – there [sic] too many to put them all on this map’.98 Such venues attracted young, socially fluid and racially mixed audiences, although Harlem’s nightlife was racially divided into establishments that catered for and were run primarily by and for white clientele, and those which were operated by Black-Americans aimed at a black or mixed race clientele. The map signals some of these inflections. The Savoy Ballroom, situated on Lenox Avenue between 140th and 141st streets was known for its enormous dance floor, big-band jazz and gala drag balls. It was the dance palace inHarlem and famous for the Lindy Hop. On Tuesdays it hosted the ‘400 Club’, reserved for dancers at a reduced price and it filled with athletic young couples dancing. It was on Tuesday nights that Ashton went with singer Jimmy Daniels and dancer and actor Eddie Perry to ‘audition’ and recruit untrained black dancers as performers for the opera (there being hardly any ballet training schools at that time).99

Daniels was the host and cabaret singer at the piano bar Hot Cha located at 132nd Street and Seventh Avenue where it was noted ‘Nothing happens before 2.am. ask for Clarence’. Hot Cha, as singer and performer Elizabeth Welch recalled, was ‘a dive but an elegant dive. Noel [Coward] and Tallulah [Bankhead] used to go. It was ermine and pearls go to Harlem’.100 As suggested, the jazz club attracted cosmopolitan theatrical circles and drew in a sophisticated, mixed crowd of men corresponding to the circle Burra mixed with in New York. The Log Cabin Grill at 168 West 133rd Street is designated in Campbell’s map by a female performer singing the blues accompanied by a pianist with the note ‘An intimate little spot’. It was celebrated for its blues singers, notably Billie Holiday, and was infamous for its smoke-filled atmosphere of marijuana and the smell of hog maw (fried tripe). And Gladys’s Clam House was given a star in the map besides staying open all night for ‘Gladys Bentley wears a tuxedo and high hat and tickles the ivories’, signalling to those in the know what kind of woman she was.101

Burra’s understanding of Harlem life and Black-American culture was framed, as usual, by second-hand sources, notably the illustrated press, especially Vogue and Vanity Fair and entertainment and film magazines such as Variety. It was also informed by the dominant European racial stereotypes encountered in popular literature and entertainment before he had arrived in New York. He had read the sensationalised and controversial novels of Ronald Firbank, including Prancing Nigger (1924) and Carl Van Vechten’s Nigger Heaven (1926), which presented the wilder side of Harlem life with its drugs, sex trade and brawling and which contentiously aligned black sexuality to criminality. He also collected jazz and blues music by Bessie Smith, Ethel Waters, Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington and Billie Holiday among others, buying imported discs from Foyles on the Charing Cross Road and Levy’s in Aldgate, London, from the early 1920s.

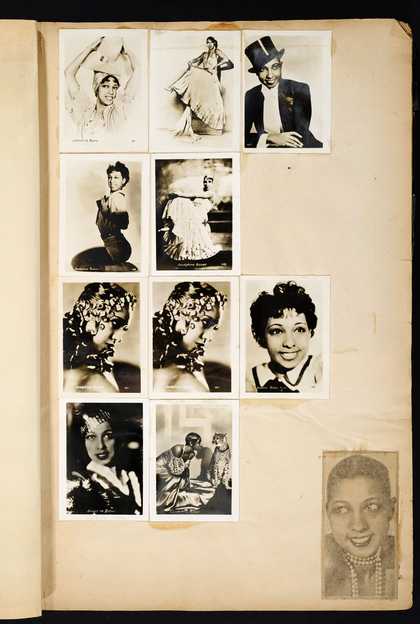

Fig.12

Photographs of Josephine Baker in Edward Burra’s scrapbook c.1929–36

Scrapbook TGA 939/8/1 no.8

© Edward Burra

Burra knew the ‘New Negro types’ of Mexican illustrator Miguel Covarrubias that had been reproduced in Vogue in April 1927.102 Covarrubias had also designed the sets for La Revue Negre in which Josephine Baker first performed in Paris in 1925 and which Burra had seen with Chappell.103 Burra collected postcards and photographs of Baker that he pasted into his scrapbooks (fig.12).104 He saw her in the film Siren of the Tropics (1927) in October 1927 noting that ‘Ciné Mirror is full of it’ enclosing a postcard still of the film from Paris.105 Burra bought many records of her songs and he saw Baker perform many times in London and Paris.106 He wrote to Ker-Seymer in February 1933:

Went to the Casino de P[aris] revue, glorious my dear. Ive [sic] never enjoyed so much for years. J[osephine] Baker rose out of a gilded casket in a green evening dress to the floor trimmed with diamonte & sang ‘King for a day’ in English. Never have I heard anything so lovely. She also appeared as a native maiden in a dramatic sketch which was glorious.107

This background reinforced European conceptions of the highly sexualised nature of black performance which the commercialised worlds of nightclubs, revues, the press and the film industry all eagerly exploited. If this approach corresponded to a trope of negrophilia among white American and European intellectuals in the 1920s and 1930s, which mythologised Harlem as a hedonistic, bohemian playground associated with the vogue for the ‘New Negro’, it was simultaneously marked out, as art historian Petrine Archer-Straw has noted, as a site of ‘something fantastic and modern’, as ‘a place of spontaneity and improvisation, of energetic lively music; a place of violent bodily motions, erotic gestures and sexual freedoms’ celebrated in jazz and blues music and evidenced in dances such as the Lindy Hop. 108

Burra’s art was transformed by his encounter in 1933–4 with this African-American and Hispanic-American cultural fluorescence that held the potent promise of a new black- and Latino-inspired cosmopolitanism; one that was socially and sexually fluid and appeared to test society’s racial and sexual limits. Some works completed during this visit repeat the Rossi strategy informed by photojournalistic exposés, assuming a viewpoint from the auditorium when watching the racy burlesque acts such as Strip-Tease 1934, while inspecting fellow audience members, or checking out the clients at the counter in an all-night diner as in Oyster Bar, Harlem 1934–5.

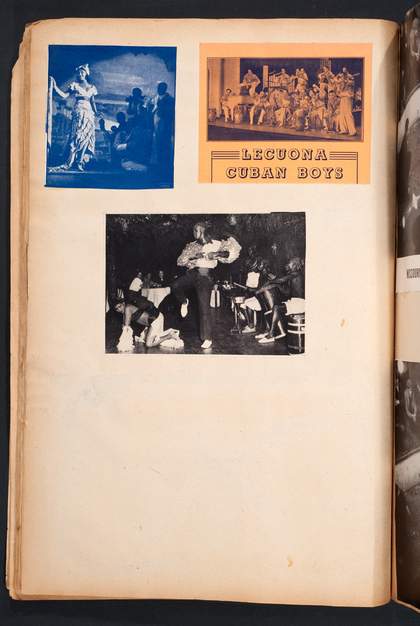

Fig.13

Press cuttings of the Lecuona Cuban Boys in Edward Burra’s scrapbook c.1929–36

Scrapbook TGA 939/8/1 no.10

© Edward Burra

Fig.14

Photograph of the actor Rudolph Valentino in Edward Burra’s scrapbook c.1929–36

Scrapbook TGA 939/8/1 no.6

© Edward Burra

However, key works examine the interrelationship between modern nightlife, masculinity and performance in light of these altering approaches to ethnicity and sexuality. Burra’s images of black and Hispanic performers in Harlem Theatre 1933, Red Peppers 1934–5 and Cuban Band 1934–5 testify to his enduring fascination with the distinctive appeal and homoeroticism of the Latino male performer. His scrapbooks contain images of the Lecuona Cuban Boys, a Cuban band that toured internationally and which had popular hits with rhythmic ‘tropical’ rumba music that exploited the appeal of physical dances such as the rumba and the conga (fig.13). In these years, the archetypal Latin heartthrob and matinée idol who had enormous popularity with female audiences was the film star Rudolph Valentino, whose postcards Burra collected and whose photographs took up pages in Burra’s scrapbook (fig.14). His good looks and dramatic acting style heightened an awareness of the male body and his performances encapsulated a smouldering passion that made him ‘the male equivalent of the vamp’.109 One critic commended his sensualised expression and sexualised dancing when cast as an Argentine cabaret dancer and tango pirate for its ‘heavy exoticism, compelling fascination, perhaps [even finding it] a little disturbing’.110 In Red Peppers the band’s Latino machismo, suave seductiveness and exotic handsome looks are clearly placed in the spotlight as they are portrayed by Burra in their tight-fitting stage costumes with glittering lapels. Their compelling exoticism and erotic appeal is further reinforced by the symbolism of the enormously luscious heart-shaped red peppers of the stage set suspended overhead and by the large red cactus in the foliage.

This analysis of Burra’s representation of the thriving inner-city cultures of Paris, Marseilles, Toulon and Harlem has opened up the complex and highly sophisticated ways within which Burra, and many inter-war artists, photographers, filmmakers and consumers approached and understood the significations of modern urban life as it was developing in the 1920s and early 1930s. It started with the overwhelming popularity and mainstream commercialisation of entertainment, dance and cabaret in London: the big bands, the nightclubs, the grand hotels, the American crooners and the ‘Midnight Follies’ cabaret shows. The Argentine tango, the Lindy Hop and the rumba have been highlighted as sensational features of the entertainment and nightclub scenes of Paris and New York and linked indelibly to the era’s fascination with dance and in the popular imagination to the figures of the Apache gangster, the Harlem dancer and the Latino cabaret singer. The bals musettes on the rue de Lappe with their permissive atmosphere, the portside cafes and sailors’ bars in Marseilles and Toulon with their tantalising homosocial possibilities, and the energetic dance halls, the lush, smoke-filled cabarets and intimate jazz bars of Harlem valued for their racial and sexual freedoms, have all been highlighted as significant in Burra’s work. It is evident that Burra mixed in liberal circles at home and abroad that promoted more relaxed and tolerant approaches towards gender, race and sexuality and that such attitudes formed the basis of an emancipated cosmopolitanism. Nevertheless, at a time of the most extensive and heterogeneous interface of the mass media and film with global consumers, the view of city nightlife that Burra crafts is inscribed as much with meanings from illustrated magazines, film books, postcards, photographs and films stills as it is indebted to his first-hand experience. Given the rapidly expanding visual culture of the 1920s and 1930s, generated by the commercial power of the mass media and film industries, these popular cultural inscriptions had a profound impact upon contemporary art engaging with such themes and with its interpretation. As the Tate Gallery director John Rothenstein so correctly noted about Burra in his 1945 Penguin Modern Painters book, his pictures did indeed ‘constitute the most grand and the most vivid interpretations of the least reputable seams of society by any painter of our time’.111 However, they did so in a thoroughly updated and sophisticated manner. Burra saw the entertainment scenes of London, Paris, Marseilles, Toulon and Harlem as the material out of which to shape compelling representations of modern social, sexual and racial identities and to configure new ways of modern bohemia – even when the artist was located at a distance, painting in his studio back bedroom in Rye, surrounded by piles of magazines, postcards and photographs and listening to jazz music.