Today with photography we can communicate our thoughts, conception and realities, to all the people on earth; if we add the date of the year we have the power to fix the history of the world.

August Sander 19311

In autumn 1926 a remarkably tenacious post-office clerk turned private art collector, Kasimir Hagen, staged an exhibition at his newly opened Richmod Galerie on Cologne’s Richmodstrasse. New Art, Old Art (Neue Kunst, Alte Kunst) juxtaposed works by contemporary German artists with an eclectic selection of older artworks from Hagen’s personal collection, including medieval wood carvings, nineteenth-century paintings and antique furniture. In his 1955 autobiography, Hagen outlined the history of his collection and recounted the cultural milieu in Cologne in which he was able to foster his passion as an amateur art collector. According to his own account, he had built up one of the best personal collections of antique and contemporary art in the city as a result of his ‘single-mindedness and hard work’ in seeking out advice from experts, art historians and curators, as well as learning about art through journals, exhibitions and lectures. The occasion of the 1926 exhibition marked his and his wife’s physical relocation from a flat in the suburb of Köln-Deutz to a new and much larger home in the heart of the old city in Neumarkt. Hagen later remembered:

Since I had a lot of room in my new flat, I had the idea to give up the first floor of the house as exhibition rooms for a Progressive group of painters under the name of ‘Richmodgalerie’ whose activities created a strong external impact. I supported modern painting, particularly by the following artists: Jankel Adler, Gert Arntz, Max Ernst, Marta Hegemann, Heinrich Hoerle, Anton Räderscheidt, Franz W. Seiwert, Gert Wollheim … It gives me great joy that the works of these painters are still much appreciated today … In conjunction with the exhibition, I published a small book with 28 reproductions of the paintings and portrait photographs of the painters and some of my older art objects … it was received very well, especially the paintings, which for 1926 were very provocative. Many of the catalogues were sent abroad, some to the USA. I was able to help the painters exhibit their works to collectors and museums without any personal financial gain. The conduct with the artists who were there was very refreshing and brought me new stimuli, as well as the opportunity to buy new pictures.2

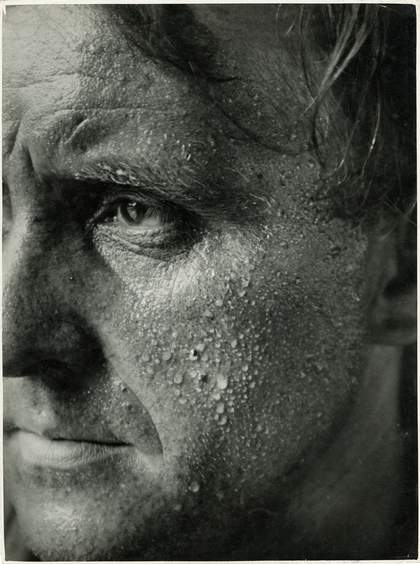

With the catalogue, the exhibition offers evidence of wider networks of visual exchange among the Cologne avant-garde during this period. In particular, it testifies to the inter-connections between the artists included in the exhibition and the relationship they had with the Cologne-based photographer August Sander (1876–1964), responsible for producing the portrait photographs of the painters referred to by Hagen and whose role within the Cologne art scene was far more integrated than standard art historical scholarship has indicated.

Sander is best known for his unfinished, gargantuan ethnographic documentation project People of the Twentieth Century (Menschen des Zwanzigsten Jahrhunderts), which was conceived as ‘a cultural work in photographic pictures divided into seven sections, grouped in classes and comprising circa forty five portfolios’.3 Each portfolio was categorised according to different themes and each one was to contain twelve photographs. Most of the artists, architects, performers, musicians and writers who made up the Cologne cultural scene of Sander’s era were included in different guises, accompanied by a host of other sitters, both known and anonymous, from all walks of life in twentieth-century Germany. The project was originally conceived in 1910 but was not formalised by Sander until the mid-1920s, although the photographs eventually included in subsequent and posthumous reconstructions of the project range in date from 1892 to 1954.4 Sander’s contention, cited in the epigraph to this article, that in photography ‘we have the power to fix the history of the world’, was a bold one indeed. It was borne of the confidence and optimism in the creative power of technological modernity, the darker under-belly of which did not manifest itself overtly until the onslaught of National Socialism.

The historiography of People of the Twentieth Century, from its inception in 1910 to its first and second published manifestations during Sander’s lifetime – in 1929 (under the title Face of Our Time (Anlitz der Zeit)) and in 1962 (Mirror of Germans: People of the Twentieth Century (Deutschenspiegel: Menschen des Zwanzigsten Jahrhundert)) – is troubled by political contexts, in particular by the global development of an interest in eugenics, physiognomy and the classification of facial types as a mode of surveillance and social judgement that began in the long nineteenth century and took on particularly sinister forms in Germany under the Third Reich.5 Disentangling Sander’s project from the more over-determined readings of its political ramifications within Germany in the first three decades of the twentieth century requires careful archival analysis and close attention to the visual artefacts.

Critical commentary on the project since the 1970s has focused largely on its place within the contradictory politics of Weimar culture, rather than on individual photographs. For art historian George Baker, writing in October in 1996, Face of Our Time shared dangerous ground with National Socialist theories of social Darwinism and racial empiricism in what Baker describes as ‘Sander’s intended narrative of social decay’.6 Baker’s reading is founded on a misconception of the class structure of the project as one that privileges the bourgeoisie, and as such one that is inevitably conservative in the face of the crisis of portraiture within modernism.7 More dialectical readings, however, can be found in an earlier article by art historian Steve Edwards published in the Oxford Art Journal in 1990, and a subsequent piece by art historian Andy Jones that appeared in the same journal a decade later.8 Jones traces a brief historiography of Sander’s project, carefully weighing up the conflicting claims that have been made for it. These range from the misplaced rhetoric of Sander’s own stated ambitions to objectivity; writer Alfred Döblin’s support of the work as presenting the ‘truth … made ready’; philosopher Walter Benjamin’s analysis of the project as a radical one that offered ‘a training manual’ with which to study German society in the present with a view to a revolutionary future; photographer Allan Sekula’s reading of Face of Our Time ‘in terms of the discourse of the instrumental archive’; and finally Jones’s own reading of the project as an extension to Steve Edwards’s Bakhtinian refusal to read ‘the photographic portrait as the site of a monological discourse of power in which the sitter is a passive object’.9 Instead Jones suggests that the photographic portrait should be seen ‘as a dialogue in which the sitter is, to some extent, a self-authoring subject’.10

By adopting this strategy it is possible to look more closely at the fields of signification at play in the individual photographs within Sander’s scheme, and foreground the contradictions within it as inevitable to a project that attempts to document and create taxonomies of different spheres of social life. The example of the New Art, Old Art exhibition offers a significant point of departure for such an ambition. A letter written by the painter Anton Räderscheidt to the critic Franz Roh on17 June 1926 provides evidence that the exhibition was conceived as the basis for the foundation of a new artists’ association:

We have created an association to include the following painters: Jankel Adler, Gert Artnz, Marta Hegemann, Heinrich Hoerle, Anton Räderscheidt, Franz W. Seiwert. These are the West German painters whom we consider to be the essential nucleus and who are seen as such by the other side in many exhibitions. We have spoken out for and agreed on every aspect amongst ourselves. From July onwards our works will be exhibited permanently in the newly opened Richmod Galerie in Richmodstr. 3, on a rotational basis. I have a contract with the Gallery’s owner, Mr Casimir Hagen, who has given me the possibility to construct the exhibition as I see fit. For the first exhibition, we shall be publishing a picture book with no text, in which we shall include 3–4 illustrations of works by the aforementioned artists … Unfortunately you were unable to see much of Seiwert’s or Hegemann’s works on your visits – we accord great importance to both of these artists. I would ask you now to trust us, also in the event of one or the other distancing themselves from you. Incidentally you will find the photographs informative. Whenever possible I would like us to appear in close conjunction. We would like to add Max Ernst and Gert Wollheim to our group, but I have not yet received a reply on their behalf. I shall, of course, keep you up to date on how the whole thing develops.11

The new artists’ association to which Räderscheidt refers was probably a sub-set of the already loosely formed group known at the Cologne Progressives, led by Seiwert and Hoerle and to which Sander, Arntz, and others in their circle also belonged or were associated with (fig.1). The Cologne Progressives had emerged after the dissipation of dada in Cologne and were aligned to a specifically radical Marxist political agenda. However, the group have generally been marginalised from standard art-historical accounts of revolutionary art during the Weimar period, largely as a result of their ongoing commitment to, though palpable struggle with, the role of easel painting in an age of radical politics. While the Progressives’ Weimar contemporaries privileged the revolutionary potential of easily reproductive media, particularly photography, photomontage and woodcut prints, the Cologne Progressives, above all Hoerle and to some extent Seiwert, continued to privilege easel painting alongside their graphic work. They also maintained a specific interest in the relationship between the surface facture of the work and what they referred to as ‘the worker-viewer’s’ experience. For the Progressives, if the worker was the backbone of society, then art ought to be a manifestation of the organisation of work, since it was only through the visible revelation of the structure of society through work that the ruling classes could be dismantled. Thus it made no difference what medium the structure of society should be revealed in to the ‘worker-viewer’ of their art.12 Significantly, in 1921 Seiwert had produced a series of polemical drawings entitled Seven Faces of the Time which Arntz followed up in 1927 with a portfolio of woodcuts entitled Twelve Houses of the Time. The typological structure of both sets of work was clearly the inspiration for Sander’s production of the 1929 edition of Face of Our Time. While the documentary ability of photography freed the Progressive painters to pursue goals in painting other than mimetic representation, the structural and typological philosophy of their paintings allowed Sander to conceptualise his photographic practice in a specifically typological fashion. The exchange between the painting and photography of the Cologne Progressives was clearly significant for both media.

In line with Räderscheidt’s ambition, Max Ernst and Gert Wollheim did become members of the newly proposed artists’ association, despite lacking any radical political affiliation. It is telling that Ernst’s catalogue entry was written by Hoerle, and Wollheim’s was extremely sparse, indicating the likelihood that neither had replied to Räderscheidt in time. Adler’s entry was written by Seiwert, suggesting that perhaps he too had not responded in time. Nevertheless, keen to pursue his contract, Räderscheidt ensured that all three artists were represented by some significant paintings from their respective oeuvres: Ernst’s La Belle Jardinière 1923, Wollheim’s Farewell to Düsseldorf 1924 and Adler’s Jewish Man Bathing 1925 (one of a series of portraits of Jewish men) among them. There are no extant installation shots of the exhibition but the catalogue, designed by Räderscheidt with input from Hegemann, Hoerle, Seiwert and Sander, provides clues to its design and intended affect. Each artist, apart from Wollheim, was represented by a portrait photograph, a pithy aphorism that summarised their artistic concerns, and reproductions of two of their exhibited works.

Most of the portrait photographs of the artists in the catalogue were taken by Sander, and also appear in either his 1929 publication Face of Our Time or in the posthumous seven volume People of the Twentieth Century (fig.2).13 Wollheim was represented by a striking full-length self portrait and a minimal line announcing that he was ‘born in Berlin and lives in Berlin’. Hoerle’s entry for Ernst noted that ‘he was born in Cologne and lives in Paris’ and continued with typical dadaist hyperbole: ‘Max Ernst to whom God gave his little finger, today walks with him arm in arm over the boulevards of the world’.14 In his own catalogue statement Arntz comments: ‘Important for me is the strict utilisation of the simple possibilities of the wood panel and the surface. The results: a graphic art without coincidences and a plastic picture; both are good ways to demonstrate the events of our lives re-formed, succinct and rigorous.’15 Accompanying the statement and Sander’s portrait photograph of him were photographic reproductions of two of his relief carvings. For Arntz, the materiality of wooden blocks was more significant than the two-dimensional prints that might be taken from them. Steam Roller is a celebration of technology and the machine in an urban industrial scene, while Suburban Street highlights a more traditional set of values: facades of houses and shops, a few figures on the street and a resting horse are all depicted in strong linear contours with stark contrasts between ground and relief. Significantly, as curator Lynette Roth has observed, Arntz ‘increased the tactility of the plate by gluing a wooden figure onto its surface over the shape of his own carved, uniformed figure. The relief has not only been made more tactile but also unprintable’.16 Both blocks also include images of children, revealing the artist’s conceptualisation of the past, the present and the future within his graphic programme.

Heinrich Hoerle’s entry bears traces of his dadaist informality in both the aphorism and the photograph, a more informal interior shot taken in front of what is probably one of his own paintings, holding a pipe and looking away from the camera. He wrote of himself: ‘Fanatics for constructivist destruction. Absolute relativity in painting. Result Totalism.’17 Hoerle’s Factory Worker 1921 and Female Factory Worker 1926, when seen together, point to a shift in the artists’s painterly style from the faceless and dehumanised mechanistic robot of the earlier painting to the downtrodden but closely rendered proletarian portrait of 1926.

Franz W. Seiwert wrote in his catalogue entry: ‘With my pictorial form, I try to depict a reality which has been stripped of everything that is sentimental or coincidental. To make visible its legitimacy, its functions, its connections and its tensions within the picture frame.’18 Accompanying his portrait photograph by Sander were two reproductions, also taken by Sander, of his paintings Closing Time 1925 and Demonstration 1926. For Seiwert the documentary possibilities of the ‘New Photography’ gave the painter extra freedom to pursue non-mimetic representation. Sander was specifically commissioned to photograph the artwork of the Cologne Progressives and their circle so that they could disseminate it to as wide and international an audience as possible. As Roth has commented:

The Progressives’ excitement about photography’s ability to introduce their work to a broader public is inextricably tied to Sander’s investment in capturing the subtleties of a given surface … The Cologne artists repeatedly praised the photographer’s reproductions, even further encouraging him to capture the ‘plastic’ or tactile quality of their artwork … Sander’s own emphasis on ‘exact photography’ made his work a crucial component of the painterly project of the Cologne artists.19

Like Arntz’s and Hoerle’s works, the subject matter of Seiwert’s two paintings was characteristic of the Cologne Progressives sympathy with left-wing politics. Indeed, the socio-political concerns of Seiwert, Arntz and Hoerle come through very clearly from their choice of reproduced works, and stand in marked contrast to the choice of works by Hegemann and Räderscheidt, indicating the increasingly divergent political paths of the group.20

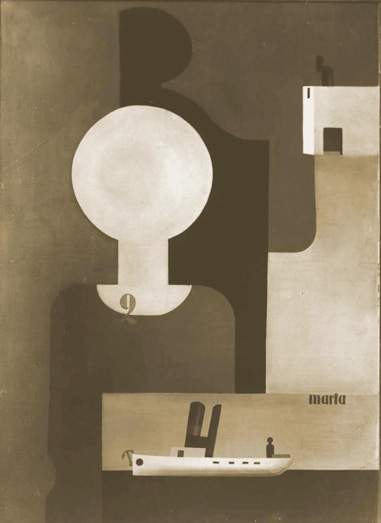

Marta Hegemann’s two representative catalogue works were a 1921 watercolour, Small Sailing Boat, which was typical of her early watercolour style and subject matter, and the now lost painting Female Painter 1926.21 It can be assumed that the eponymous Female Painter is a self portrait. The artist stands on a rug in front of her easel facing the viewer and holds a paintbrush in both hands in front of her lap. Her studio is crammed with the standard elements of her iconography: a small statue of a tree and a horse on a shelf behind her, a coffee pot, some oil lamps, an open book and two cats circling her feet. She stands in front of the easel on which rests a canvas portrait of a man’s head and torso, possibly that of her husband, and perhaps also the implied viewer of the work, whom she engages directly. Behind the easel is a balustrade indicating the realm of possibility and freedom beyond this interior scene.

Significantly, Räderscheidt’s two catalogue works were of Hegemann. Picture of Marta 2 1920 (fig.3) and Painter and Model 1926 (fig.4) succinctly demonstrate the stylistic development of Räderscheidt’s art between these two dates. The constructivism of Picture of Marta 2 has been replaced by the New Objectivity of Painter and Model. New Objectivity is notoriously difficult to define. Never a formal movement or style, it was a term most commonly attributed to Gustav Hartlaub, Director of the Kunsthalle in Mannheim. Hartlaub sought to identify the tendencies he had perceived in post-First World War art in Germany after the demise of expressionism. Common characteristics include the precise (or ‘exact’) rendition of material objects or people, confined within a static or airless space, without necessarily any logical relation to one another.22 While the sitter in Hegemann’s Female Painter is clothed, Räderscheidt’s nude portraits of his wife in the uncanny environment of the artist’s studio veer from anonymous chess pieces to fully nude puppets. For Räderscheidt it was undoubtedly Hegemann who served as inspiration for his work, whereas Hegemann is more fascinated with herself, a visual dynamic that was not lost on Sander.

Fig.3

August Sander

Photograph of Anton Räderscheidt’s Bild Marta 2 (missing or destroyed)

Private Collection

© SK Stiftung Kultur, Bonn/All Rights Reserved DACS 2013

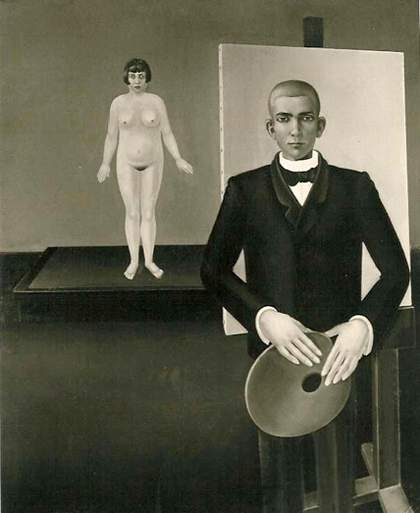

Fig.4

Anton Räderscheidt

Painter and Model 1926 (missing or destroyed)

© DACS, London 2013

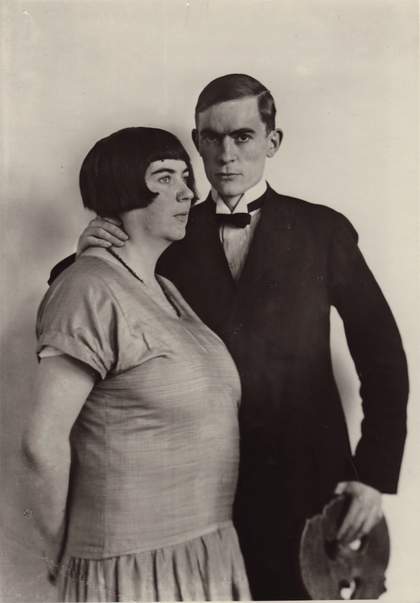

Fig.5

August Sander

The Painter Anton Räderscheidt and his Wife Marta Hegemann c.1925

© Die Photographische Sammlung/SK Stiftung Kultur-August Sander Archiv, Cologne/All Rights Reserved DACS 2013

In Painter and Model, a tuxedo-wearing Räderscheidt faces the viewer in line with the front plane of the canvas. He holds a clean palette in his hand and his legs disappear into the wooden struts of the easel, so that he literally merges with the tools of his profession. The blending of the palette in his hands with the struts of the easel/legs is echoed wittily in a palette-like object being held by Räderscheidt in one of Sander’s many photographic portraits of the artist couple (fig.5). In both images staged performativity and the artifice of construction is paramount to the surreal effects created. Räderscheidt plays a visual game with the viewer and Sander attempts to recapture something of its essence in his photograph. The strangeness of the painting is underscored in a number of ways in Sander’s photograph. In the painting, Räderscheidt’s position is impossible perspectivally, inserted as he is between the easel and the canvas, calling into question the identities of painter and model – while academic convention would determine the naked woman to be the model and the clothed man the painter, Räderscheidt undercuts these easy identifications. Although the nude is posed on a podium in the infinite background waiting to be painted, her role as object of the artist’s gaze is thrown into question. The fictional painter has turned his back on her and looks instead to the viewer while sandwiching himself onto the canvas in her place. The artist and the model are both subject to Räderscheidt’s and the viewers’ gaze. Along with others in a series of Painter and Model canvases produced by Räderscheidt throughout the late 1920s, this work explores a set of ontological questions concerning the nature of subjectivity and representation, rather than simply rehearsing the stylistic sobriety of New Objectivity. It is this performative aspect of Räderscheidt’s practice that Sander also stages in his photographic representations of the painter with his artist-wife-cum-muse and model.

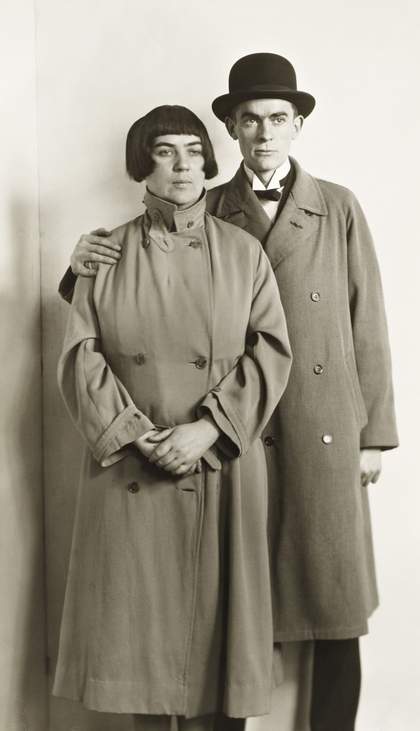

Fig.6

August Sander

The Painter Anton Räderscheidt and his Wife Marta Hegemann c.1925

Tate AL00045

© SK Stiftung Kultur, Bonn/All Rights Reserved DACS 2011

In Sander’s many photographs of Marta Hegemann and Anton Räderscheidt, the artists either appear together as a self-consciously constructed Künstlerehepaar or artist couple (fig.6), or separately as individuals, and are presented within multiple contexts in People of the Twentieth Century: in volume 3 (The Woman), volume 5 (The Artists) and volume 6 (The City). They also circulate most often as signifiers of the visual sobriety endemic to Sander’s practice of ‘exact photography’. As already indicated, through their close involvement with New Art, Old Art, Hegemann and Räderscheidt were both active members of the Cologne art scene during the Weimar Republic, and after a brief flirtation with dada moved in the same the circles as the Cologne Progressives, although they remained aloof from the Progressives’ more radical political concerns.23 When viewed together and in conjunction with the artists’ painterly self-constructions, Sander’s various photographs of the couple, spread across several different volumes of People of the Twentieth Century, reveal the complexity of their dialogic performances with the photographer, each other and the viewer. Close analysis reveals the distinctly carnivalesque irony at work in these images, positioning the photographs somewhat against the grain of their status as representative examples of ‘exact photography’ or New Objectivity. By examining the photographs and the paintings alongside one another it is clear that visual relationships between the two media within the discourses of realism and New Objectivity were being self-consciously explored.

Fig.8

Anton Räderscheidt

Young Man with Yellow Gloves 1921

Private collection

© DACS, London 2013

At first sight it might seem as though the traffic of influence between Sander and the artists was a conventional one-way street in which Sander simply attempted to replicate in photographs the self-fashioning of the artists on canvas in a photographic tableau vivant. Indeed, Sander’s 1926 portrait of Räderscheidt (fig.7) is a clear indicator of that type of transmission, for it is probable that Sander wanted to re-capture the look of Räderscheidt’s self-fashioning from a number of the artist’s self-portraits, including the 1921 painting Young Man with Yellow Gloves (fig.8). In his photographs of Räderscheidt, Sander went to some lengths to re-construct the illusion of empty space, clean lines and receding perspective characteristic of Räderscheidt’s paintings. For example, early one Sunday morning Sander surprised the artist by asking him to pose on the normally busy Bismarkstrasse while it was still empty, taking four different versions of the shot.24 Sander clearly intended to align his photographic image with Räderscheidt’s own self-fashioning by expunging unnecessary details and creating an ‘objective’ environment.25 However, it is also known that Räderscheidt subsequently used Sander’s photograph to reinforce his own painterly concerns, choosing the exact same image to accompany his epigraph in the New Art, Old Art catalogue: ‘I am 34 years old and was born in Cologne. I paint the man with the bowler hat and the hundred percent woman who steers him through the picture. My fondness for the horizontal and the vertical is a means of guiding the observer through my pictures.’26 The phrase is significant as a summary of Räderscheidt’s painterly concerns: portraits of himself fully clothed in formal attire and his wife Hegemann often fully nude, engaged in sporting activities and rendered in a coolly detached style.

The staged performativity of Räderscheidt’s paintings, the visual games he plays with the viewer, and Sander’s attempt to recapture these elements can be seen in several other photographs taken on the same shoot as the one in which Räderscheidt, standing with Hegemann, holds a palette-like object (fig.5). However, in these subsequent photographs everything changes: Räderscheidt drops his grip and looks intently at his wife; Hegemann looks away towards the spectator but into a middle distance of her own contemplation, the suppression of a wry, fleeting smile across her face, caught forever in stasis. Sander’s photographs of the couple can also be read in dialogue with several further images from the same shoot (as signified by Hegemann’s clothes, accessories and hair) in which Hegemann appears alone. In one version, which she subsequently used for her driving licence, she is photographed without any make up, indicating that it was probably taken first. However, in the version included in her Richmod Galerie catalogue entry, she decorated the side of her face with key motifs from her painterly iconography: two birds in flight, one with a crucifix on its wing (fig.9). In yet another version (which appears later in volume 3 but under the simple title Female Painter in a portfolio called The Woman in Intellectual and Practical Occupation), the tattoo has been redrawn to include two birds, a star, waves, a heart, some steps and a cross. Presented alone and without the constrictions of her husband’s grip, Hegemann has chosen to present her professional face to the camera as one in which her identity is literally written on her body via the drawn tattoo of her personal artistic symbols.

Fig.10

August Sander

Lumpenball Em dekke Tommes 1929

Private Collection [Gerd Sander]

© SK Stiftung Kultur, Bonn/All Rights Reserved DACS 2013

One of the overriding ways of understanding the self-constructed dynamic between Hegemann and Räderscheidt is to regard their relationship as one that fluctuated between individual ambition and collective endeavour, and that it was through photography, in particular Sander’s photographic portraits, that they played out their self-constructed roles most subversively. The constructed nature of the New Objectivity aesthetic suited the couple’s carnivalesque irony and sardonic humour. Central to both artists’ work were explorations of performative and subjective identity through visual representation in painting, photography and masquerade. Steeped in medieval Christian tradition, Cologne’s annual carnival celebrations began in the twelfth century and have long been embedded in the cultural lives of the city’s inhabitants.27 The festival ultimately consists of a standard set of themes, the most essential of which is the ‘the reversal phenomenon’, or what philosopher Mikhail Bakhtin more famously termed ‘the carnivalesque’.28 Folk historian Peter Tokofsky explains that ‘it is the world turned upside down in which status, age, wealth and most prominently gender get turned on their heads’, while historian Reid Mitchell remarks that ‘the most notorious yet long-lived Carnival tradition was that of cross-dressing’.29 Significantly, philologist V.V. Ivanov notes that ‘the inversion of the binary opposition male/female … appears to be a determining factor in a significant number of carnival rites involving status reversal’.30 At the Cologne carnival social and gender hierarchies are inverted, in particular during Weiberfastnacht (women’s carnival) when ‘women reign supreme’, never being refused a drink or a kiss, tipping the hats of passing men, dancing in public and playing practical jokes on any men they encounter.31 Husbands must either stay at home and look after the house or step outside and run the risk of being mocked.32 While this ‘reversal’ may no longer be deemed so radical today, historically Weiberfastnacht carried far greater symbolic significance. It presaged the ‘Three Crazy Days’ in which the medieval fool dominated festivities, and it was also during these ‘crazy days’ that the exclusive Lumpenbälle, or costumed balls specifically reserved for artists, were attended by Hegemann, Räderscheidt and their peers and photographed extensively by Sander. In one photograph (fig.10), Sander portrays Hegemann and Räderscheidt in convivial mood as they celebrate the evening together, a far remove from the sobriety of the portrait photographs considered above. Indeed, Sander’s importance to all of the artists of the Cologne avant-garde is traceable throughout their activities both as a group and as individuals. In other shots from the same evening Hegemann and Räderscheidt are shown posing among a group of their friends associated with the Cologne Progressives, including Heinrich and Tata Hoerle. Although Räderscheidt and Hegemann increasingly distanced themselves from the politically engaged artwork of the Progressives, they did continue to fraternise with them, particularly on social occasions, such as at the Café Monopol and the Lumpenbälle, as well as at exhibitions and on a number of public political protests.33

A collaborative opportunity for the group arose once more in 1929 via a specially commissioned exhibition entitled Space and Mural Painting, the study of which demonstrates how significant Sander’s role was as photographer of the Cologne avant-garde. Having already helped construct artistic identities by taking portrait photographs of the same artists for the 1926 New Art, Old Art exhibition catalogue, Sander used Space and Mural Painting as an opportunity to expand his documentary repertoire of individual portrait subjects while incorporating the study of interior design, painting and architectural settings. With the help of Heinrich Hoerle (fig.11), the Cologne architect Hans Heinz Lüttgen (fig.12) conceived the exhibition as a Gesamtkunstwerk (total work of art) for the Cologne Art Association by arranging the spaces and designing the interior and the furniture for them.34 He then commissioned various artists to provide the murals for the different rooms. Not surprisingly the commission was divided along gender lines, and as the only female artist to be included Hegemann was somewhat inevitably assigned to decorate the children’s nursery. Other commissions went to Fritz Kronenberg, was painted the reception room, Jankel Adler, who was assigned the living room, Heinrich Hoerle the library, Richard Seewald the dining room, Franz W. Seiwert the office; Lüttgen the rooms for the display of carpets, wallpaper and materials, and Anton Räderscheidt and Heinrich Maria Davringhausen the central room at the heart of the house. On 17 March 1929 Cologne critic and Progressive member Walter Stern gave a talk about the exhibition broadcast on West German radio. The introduction was also published in the West German Radio Magazine and subsequently reprinted in the accompanying exhibition catalogue. Stern explained that ‘the intention was to illustrate something contemporary which has the closest possible connections with the ideological and sociological facts of the epoch and suggests up-to-date correlations between the realities of society’s production and consumption’.35 He also noted that it was the exhibition’s proposed unification of ‘image and object, colour and form’ that would bring the pre-determined space ‘into a desirable relation with the social powers of contemporary collective effort’, clearly resonating with the principles of collective action that also informed the broader ideals of the Cologne Progressives. Furthermore, his delineation of the artistic process required for the successful integration of fine art objects with interior design is also significant:

The problem of the individual treatment of subjective facts in easel painting had to be addressed in order to recognise the mural as an up-to-date expression of pictorial form … it is precisely the fact that the architect organising the show created the opportunity to show … how factory and studio work complement one another that makes this exhibition worthy of serious consideration … What mattered was to relate the pictures to the space in which they found a use … the mural exists in its own cultural capacity in the context of questions put by the space.36

The rest of the catalogue included a floor plan of the exhibition followed by a detailed room-by-room guide to the individual artists and manufacturers who had contributed, accompanied by Sander’s precise installation shots. Oddly, the only room not documented in the catalogue was Lüttgen’s own architecture room of which there no longer remains any direct visual evidence apart from the probable inclusion of Hegemann’s painting The Architect 1929, bought by Lüttgen for his own collection after the exhibition.37

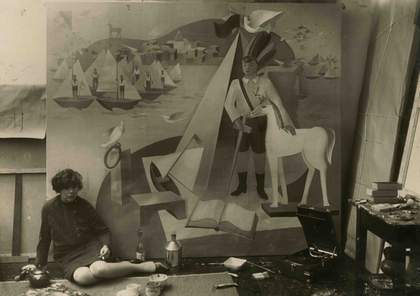

It is likely that Sander’s photographs of the exhibition served multiple functions. Not only did they furnish the catalogue but they were also supplied to the press to accompany reviews. It is clear from the positive tone of those reviews that Space and Mural Painting was a popular and a critical success, spawning several related shows including The Growing Apartment and The Home, as well as a market for Lüttgen’s interior design business called Kölner Studio, to which Hoerle also contributed for a share of the profits.38 What interested Sander was the opportunity to photograph not only the finished installations but also the individual paintings at different stages, from their execution in the artists’ studios to their installation in the gallery space of the Cologne Art Association. This was certainly true of Hegemann’s large-scale nursery murals. In one studio shot an exhausted looking Hegemann, her fringe almost covering her eyes, is shown in bohemian fashion slumped on a hessian mat in front of her finished work, cigarette in one hand, paintbrush in the other, the antithesis of the popular construct of the maternal woman who dresses neatly and keeps domestic order in a perfect home, a role perhaps implied by her position as nursery designer (fig.13). She is surrounded by the detritus of an intensive labour – there are pots, brushes and bottles strewn on the floor, a teapot with a hastily set-down cup and saucer, a gramophone in the other corner and a pile of books on a small side table – a far cry from the photograph of the clean nursery reproduced in the exhibition catalogue. In the exhibition Hegemann’s two murals – one constructed around the figure of a boy, the other around a girl – were implemented as counterparts to one another. Both children are set within a magical river scene in which sailing boats, birds, books, horses, hills and kites surround, envelop and float past them. These motifs continue on the ceiling of the play area, as well as on the lunettes in the main part of the bedroom. The ‘whole flittering cheerfulness and childlike joy of the formulation’, which captivated art critic Luise Straus-Ernst in her review of the exhibition for Die Kunst, also engaged other critics locally and nationally.39 The Rheinische Zeitung described it as ‘the most plausible and uplifting room in the exhibition’, having also noted that Räderscheidt’s black-and-white painting Nude on a Tightrope, on show in the central room, ‘fits logically with the space. Together with Davringhausen’s picture, but to a greater extent, it confirms the space-shaping idea of the mural’.40 The Kölner Tageblatt commented that ‘Marta Hegemann prepared the nursery most charmingly with painted swans, Indians, monkeys and soldiers’,41 and the critic from the Kölner Stadt-Anzeiger observed Hegemann’s lightness of tone: ‘the nursery, in which Marta Hegemann has conjured a multi-coloured child’s world of fables, is very amusing’.42 In the national press, Alfred Salomony, writing for Der Cicerone, remarked favourably that ‘the nursery deserves unrestrained admiration due to Marta Hegemann’s delightfully playful, childlike liveliness’.43 The disjuncture between Sander’s portraits of Hegemann and the critical reception of her work in the public sphere in gendered terms seems particularly significant here. While Hegemann’s works ‘delight’ their public audiences with their ‘playfulness’ and charm rather than with the ‘logic’ of her husband’s contribution, and thus reinscribe her back into the conventionally gendered realm of the woman artist, Sander and Hegemann subvert the critical association between woman, children and the domestic via their dialogic fashioning of an unruly, chain-smoking, creative and bohemian persona.

Fig.13

[ORIGINAL_CAPTION]

Although the murals for Space and Mural Painting no longer exist, Sander’s careful mapping of his friends’ artistic activities that make it possible to re-visualise not only this exhibition but also so many other aspects of Weimar Cologne’s cultural avant-garde. While Sander is famed primarily for the supposed documentary realism of People of the Twentieth Century, it is clear that the further one explores such a gargantuan project, the less ‘documentary’ it becomes. Indeed, the extent to which People of the Twentieth Century exceeds its claims to ‘objectivity’ is nowhere more self-evident than in Sander’s cannibalistic collage Cologne Goes Wild in the Year 1929 1929 (fig.14), a visual exercise in the carnivalesque. The carefully crafted photographs of friends, artists, writers and musicians that populate the pages of People of the Twentieth Century are brought together, spliced and re-arranged in a collaged celebration of friendship that ironises the typographical project. Central to the montage is the pale head of Räderscheidt as ‘hanged man’, while Marta Hegemann, looking out wryly from the bottom left, obliquely observes the viewer.44

Fig.14

August Sander

Coellen aus Rand und Band em Jahr 1929 (Cologne Goes Wild in the Year 1929) 1929

Private collection

© SK Stiftung Kultur, Bonn/All Rights Reserved DACS 2013

The extent of Sander’s involvement with the painters of the Cologne avant-garde has still to be explored within English-speaking art historical scholarship, but it is certainly clear that without his meticulous photographic records many of the artworks that were subsequently looted, destroyed or lost during the Nazi era would otherwise remain unknown today. Yet the poignancy of Sander’s photographic project rests not only on its status as documentary archive, but also on its ability to continually re-animate the lost subjects of the Weimar era’s cultural history before so many of their lives were irredeemably destroyed by the cataclysmic effects of National Socialism.