Resembling extinct volcanoes that rise to a height of ninety-five metres in places, these irregular and often top-sliced cones of burnt and oxidised waste are the residual product of a mid-nineteenth-century mining process designed to extract and distil products from oil-bearing shale for use as paraffin fuel. Mining of this kind continued in Scotland on a phenomenal scale and offered significant employment until midway into the twentieth century, by which point cheaper oil from the Middle East was lubricating western economies. Two barrels of crude oil extracted from Lothian’s ground by a unique heating process known as ‘retorting’ produced over one ton of burnt shale waste. By the mid-1860s over half a million barrels of crude shale oil were produced annually and production continued at this rate until the mines began to close between the 1920s and the early 1960s.1

Viewed from a single spot, bings might be said to have a steep front or face and a characteristically long tail, which allowed vehicles to ascend to the top to deposit burnt shale. In comparison to the notionally dormant local terrain the bings are highly changeable environments, providing a dry and windy habitat for grasses and rare plants, while small bricks and other ephemera periodically punctuate their brittle surface and serve as reminders of their industrial facture. Although the bings are not generally considered to have any public benefit, over the past four decades their quasi-Martian landscape has become environmentally valuable, offering research opportunities to conservation agencies that may help to permanently preserve them all from the threat of extraction. While two of Niddrie Woman’s four bings have already been officially classed as monuments and are therefore no longer under threat, the remaining two have been under consideration since 2006 and planning permission has already been granted to extract the second largest bing known as Niddry (the ‘Heart’ of Niddrie Woman within Latham’s scheme).

As early as 1975, however, the Scottish Development Agency, troubled by the visual presence of the bings and uninterested in their historical value, sought the advice of John Latham in his capacity as artist in residence, a position brokered by the APG which placed artists within industrial, governmental or administrative settings. According to Derek Lyddon, Chief Planner of the Scottish Development Agency at the time of Latham’s residency:

The object of APG placements may be described as ‘organisation and imagination’; to place an artist in an organisation in the hope that his creative intelligence or imagination can spark off ideas, possibilities and actions that have not previously been perceived or considered feasible; in other words to show the feasibility of initiating what has not occurred to others to initiate. Hence the product is not an art work, but a report by the artist on new ways of looking at the chosen work areas and on the action that might result.2

Latham’s conceptualisation of the bings as ‘process sculptures’ was compelling to the Scottish civil servants and initiated ideas for their conservation before legal mechanisms were put in place to protect post-industrial heritage. With the artist now dead, the challenge facing Latham supporters is, first, to ensure that all four bings that comprise Niddrie Woman are permanently conserved as a heritage site, and secondly, that this prompts fuller recognition of Latham’s sculptural concepts. Far from failing, Latham’s research and activism remains one of the keystones to the preservation of other threatened bings in the region. In the early 1980s, for instance, the Scottish Office re-invited Latham to publicly defend the classification of the Five Sisters bings as ‘monuments’, disputed by businesses keen to use the valuable shale for building material. However, the Public Enquiry did not take place following the last-minute withdrawal of the appeal, leaving Latham unable to make a similar public case for other sites, namely Niddrie Woman.3 However, like his later site-related research, including a visit funded by The Henry Moore Foundation in the 1990s, much has been archived and hidden away as unrecognised facets within a lifetime’s, albeit incomplete, project. This essay attempts to address the latter, and to promote his APG work in Scotland from the margins of his oeuvre for, despite the contemporary interest in art and ecology and the level of critical attention paid to questions of energy production and waste disposal, these reconceived piles of waste remain to be validated art historically.

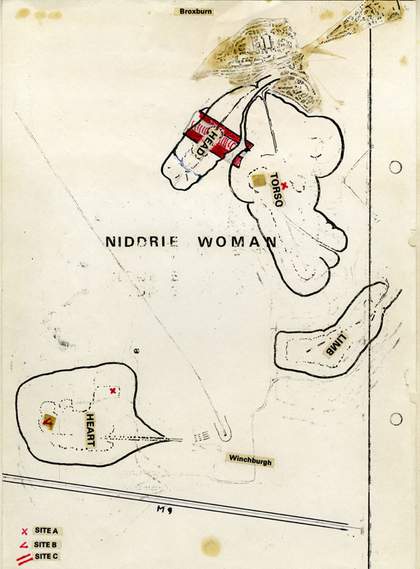

Fig.1

John Latham

Documents as Part of APG Feasibility Study – Scottish Office 1976

Tate Archive TGA 20042/9

© Courtesy John Latham Estate and Lisson Gallery

Verifiable evidence of the effectiveness of Latham’s placement in Scotland can be found in the APG archive at Tate, which includes detailed commentary, illustrations and photographs of the shale bings as well as Latham’s various proposals for interventions. Although governed by a set of practical protocols, APG placements always retained an ‘open brief’ which allowed the artist, or ‘incidental person’, the freedom ‘to spark off ideas, possibilities and actions’, while semi-predetermined outcomes partially informed by the holder’s artistic oeuvre were considered acceptable as long as the right artist was aligned with the right project. An artist’s contract concluded with longer-term proposals, known as a Feasibility Study, which included ideas for mutually agreed, realisable artwork.4 In Latham’s case, additional proposals for sea cultivation, nuclear energy, and portable video-broadcast technology for the local community all suggest that Latham networked furiously during his residency. However, his Feasibility Study lacks objective analysis and by turns is sentimental and ponderous, philosophical and stoic. His commentary is biting and highly subjective, castigating planning decisions that failed to consider ‘the bigger picture’.

Admittedly, Latham’s Feasibility Study was not designed to implant pseudo-scientific rhetoric within an already unusual contractual arrangement and its more tangible proposals were indeed coherently summarised by the civil servants. While it is unclear for whom his ambitious proposals were intended, it should certainly be presumed that Latham wished for them to become operational. In this respect it is important to iterate that, right from the beginning, Latham was seeking to make artworks befitting his own individual practice while following the APG’s and others’ methodologies. His proposals relating to shale bings synthesised personal biography (consciously or not), derived benefits from earlier articulations of the ideas of the artist Gustav Metzger relating to making auto-destructive art including fragmentation, randomness, entropy, gravity and with the developed themes and aesthetics of destruction present in his own previous work. Fortunately, his supportive hosts at the Scottish Development Agency backed this synthesis of institutional methodology and personal experience, and Latham’s intuitive reasoning was privileged throughout the placement.

Thus invited to address the question of what to do with the derelict land near Edinburgh and asked ‘from which perspective would he be looking at Scotland’, Latham pointed to a map of the country and apparently responded ‘from this distance’. An aerial viewpoint was deemed by Latham to offer a perspective and scale of an otherwise unobtainable human consciousness, and played a hugely important role in his work. His 1971 film Erth, for example, which was funded by The National Coal Board, comprises a journey through a black void space from which still images of an ever closer Earth appear, and culminates in numerous nearly illegible images from the Encyclopaedia Britannica.5 There is some kind of wilful confusion in this work but, according to the art critic John A. Walker, the viewpoint provides a metaphorical perspective that is ‘necessary if humanity is to see itself objectively’.6 Seeking once more the distinctiveness of an aerial perspective as a feature in graphic display (it is intriguing how his assemblage paintings made from books also resemble ravaged landscapes seen from above) Latham’s initial research in the Scottish Development Agency’s aerial photography archive provided his first informed glimpse of the derelict land between Winchburgh and Broxburn.

In this first, mediated introduction to the landscape, Latham determined that the largest shale bing known as Greendykes and its adjoining bings known as Niddry, Faucheldean and Albyn constituted historic documents that ‘unconsciously’ lent themselves to ‘a modern variant of Celtic Legend, namely NIDDRIE WOMAN’ (Latham’s underlining).7 Using the aerial perspective afforded by a single surveillance photograph Latham anthropomorphised Greendykes as the ‘Torso’, Faucheldean as the ‘Limb’, Niddry as the ‘Heart’ and Albyn as the ‘Head’, comprising the torn figure of a woman whose disembodied ‘Heart’ is too large to fit inside her approximately-scaled body. The Feasibility Study also mentions a visual comparison with the prehistoric carving The Venus of Willendorf (Naturhistorisches Museum, Vienna). This surrealist and perverse homage was less of an imposition than it might at first seem: the terrain of England is populated with ancient images cut into chalk hillsides, such as the Uffington White Horse in Oxfordshire and the Cerne Giant in Dorset. As an experienced traveller across England and Scotland, Latham may have sought to make the bings a comparably emblematic feature of the Scottish landscape.

The subsequent phase of Latham’s research involved on-site visits to the bings where he conducted an extensive series of topographical surveys that were more psychogeographic than cartographic. Eschewing conventional research methods, the Feasibility Study comprises snapshots and notes that record Latham’s enchantment with the huge mounds of shale, and contains little or no reliable historical information. It testifies instead to Latham’s interest in the unconscious design of the bings and how he came to notice that while their looming weightiness imposed themselves over the otherwise unremarkable residential conurbations, their summits offered vantage points and their fissures and joins provided isolated spaces for private contemplation. The Feasibility Study is also where Latham urges for the bings, being materially unique, to remain tethered to their topographical and social context in order to preserve them as unconsciously-formed sculptural monuments and to draw attention to all of their visual and mythical associations. By way of contrast, Latham’s contemporaneous photographs of Glasgow’s slum back courts, half-built motorway bridges and other oddly constructed civic features record innate failings in the urban environment formed by conscious efforts. According to the APG, commercial and civic administration more often than not suppressed, hid or simply failed to adequately support creativity, hence the need for an incidental person to work through unconscious routes. The interplay between textual and visual material in Latham’s Feasibility Study make it a reflective journal, one that gives the shale bings a meaning that simply did not exist beforehand.8

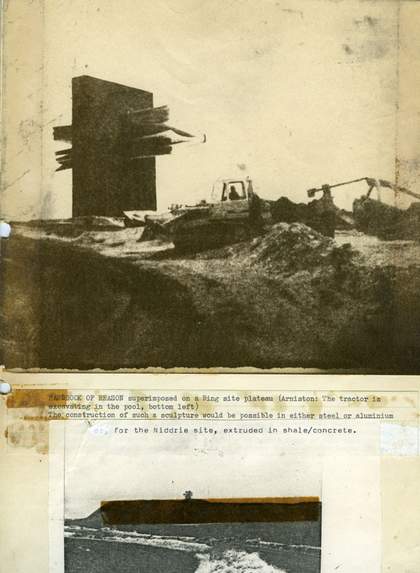

Fig.2

John Latham

Scottish Office Placement 75/76 1976

Tate Archive TGA 20042/7/1/11

© Courtesy John Latham Estate and Lisson Gallery

Niddrie Woman was described by the art critic Lucy Lippard in 1983 as a ‘pun on female earth, rebirth, modern society’s treatment of women’s bodies as castoffs, and so forth’.9 While Latham can hardly be described as a punster (if anything he was deeply mistrustful of language), gendering the shale bings and associating them with prehistory was an astute thing to do for it reconceived them for the purposes of ecological preservation and tapped into the strain of 1970s art that Lippard would later describe as the ‘upsurge of interest among avant-garde artists in “primitivism”’.10 Latham’s Feasibility Study – which makes reference to the Scottish Neolithic settlements Skara Brae and Callanish – only serves to strengthen this association, while Lippard herself compares Niddrie Woman to Silbury Hill, a prehistoric mound in Wiltshire.11 However, not only are these comparisons inadequate (Silbury Hill, despite being the largest prehistoric mound in Europe, is considerably smaller than Niddrie Woman) but they also propose a misleading relationship to prehistory when the bings are simply residual products of Victorian industry, which at the time of their making held no meaningful symbolism or community purpose other than as local deposits of waste. Furthermore, Latham’s reconception offered no practical solution to what was essentially a material problem and the strategic misapprehension of the bings as prehistoric meant that the early reception of Latham’s proposals tended towards heritage-based categories and not those of art.

The scale of Latham’s proposals was quite different from the light-footed English land art of Richard Long and Hamish Fulton, and the location of his interventions was unlike the frontier lands evoked by the work of American artists Robert Smithson, Michael Heizer and Nancy Holt. Rather, it is Scottish conceptual art that offers the most rewarding comparisons with Latham’s work – art for which transformation and transmutation were key. For example, Glen Onwin’s exhibition Saltmarsh – which inaugurated the new Scottish Arts Council Gallery in Edinburgh just prior to Latham’s APG residency – made manifest Onwin’s obsession with elementary materials and their geological importance at a coastal site near Edinburgh.12 Meanwhile the enduring popularity in Scotland of the work of Joseph Beuys (an artist with whom Latham would verbally joust), and in particular his conjoining of Fluxus artistic strategies and ritual processes that recast the emergent Duchampian tradition with a spiritual dimension, was of relevant concern to the visual arts in Edinburgh at this time.13

Fig.3

Documents as Part of APG Feasibility Study – Scottish Office 1976

Tate Archive TGA 20042/9

© Courtesy John Latham Estate and Lisson Gallery

Further south, an obvious precursor to the APG’s and Latham’s programme of research related to the mining industries was the photographic series produced by German photographers Bernd and Hilla Becher. The scholarship awarded to the Bechers by the British Council in 1966, with assistance provided by the National Coal Board, meant that the results of their photographic survey of major industrial areas in England and Wales ‘were consequently vastly better than anything [they] had been able to accomplish before’.14 Comparing the Bechers’s artistic methodology with the poetically and politically-inflected practices supported by the APG would be stretch. While the Becher’s survey is elegant and technically precise, Latham’s Feasibility Study is diffuse and ponderous. However, both are elegiac in their representation of derelict sites of energy production at a moment of industrial decline in the North.

Comparing Latham’s work with that of Gustav Metzger, however, is far more instructive, for while the looming bings were considered eyesores of spent energy by the Scottish civil servants, their material formation conformed to Metzger’s typology of auto-destructive art, defined in 1965 ‘as a form of public art … a unity of idea, site, form, colour, time and disintegrative process’, comprising falling, sliding and peeling ‘materials in various stages of transformation’.15 Latham’s proposals for the shale bings also link back to the material transformation of his own Skoob Towers (c.1964–8), which were contemporaneous with Metzger’s first auto-destructive ideas. These columns of burnt and burning books (‘Skoob’ is the word ‘books’ in reverse) intended to make ‘the viewer aware of … the indivisibility of past, present and future’, an indivisibility Latham would emphasise in his Feasibility Study.16

Surprisingly, little exhibition material was produced to record Latham’s ambitions for the bings, which included proposals for steps and notice boards, the preparation of historical records and the incorporation of commissioned artworks resulting from further artists’ placements.17 Latham’s own proposal for post-Feasibility commissioning was for a twenty-four metre iconic beacon-sculpture to be called Handbook of Reason. Although this enormous intersecting book form was rejected by the Scottish Development Agency on cost grounds, mock-ups and the Feasibility Study offer glimpses of what such a towering monument would have brought to the site if it were realised (fig.3). Its resemblance to a cruciform was noted, although the collages and sketches in the Feasibility Study illustrate a more recognisable book sculpture with interwoven pages.

This proposal is in many ways inconsistent with Latham’s advocacy of non-intervention in the landscape.18 However, Latham was operating under funded patronage, for which it would be expected he would offer proposals relating to his well-known work. More fundamentally, the intention of both strategies (of intervention and non-intervention) was to preserve the site, albeit in different ways. While the Feasibility Study makes occasional reference to those living in the locale, to community identity and to social coherence, the expediency of a proposal was to be evaluated by the internationally informed. The APG later noted they had ‘not had the means of canvassing the proposals put forward in the actual areas. The first need has been to test international opinion at its informed points on the likely subsequent acclaim, and following a positive response such as has been found, to estimate the benefits likely to accrue to the neighbourhood’.19 Latham was not therefore acting as a consultative community artist but was seeking to make a work of art that would attract the attention of his intended audience, the international avant-garde. However, while criticisms can be levelled at the ethics of this approach, history has proved that almost nothing relevant about Latham’s reconceptualisation of the shale bing complex had been transmitted effectively to either the international art cognoscenti or the local community.

Fig.4

Shale from Broxburn 2008

© StrawbleuTM

What, therefore, is the legacy of Latham’s placement? Although all the bings are considered to possess important environmental and social value, the ‘Heart’ of Niddrie Woman has been top-mined for motorway infill material to the wider detriment of the environment. The nearby Five Sisters bing complex, however, is now preserved under the Ancient Monuments and Archaeological Areas Act. Geoscientist Barbra Harvie’s 2005 report West Lothian Biodiversity Action Plan: Oil Shale Bings proposed that the area’s shale bings ‘are a unique habitat, not found elsewhere in Britain or Western Europe’, a vital recreation area and ‘a focus of community identity’.20 Her plan maintained that for such a developing and unique habitat ‘the best management of oil shale bings is no management’ as they are ‘island refugia’ with a considerable diversity of very rare plants species.21

Harvie’s report – by inadvertently contributing to Latham’s view that his artistic ideas had not been conveyed (for he thought sculpture to be a better classification than heritage) – indicates the difficulties and differences in ascribing fixed terms to a landscape. However, the four bings in question arguably benefit from having multiple meanings: Niddrie Woman is a conflation of heritage and art, and both require reaffirmation by the region’s civic and governmental authorities. In this respect it may be more worthwhile to consider the bings within a complex socio-political matrix: as landscape, leisure space, industrial monument and heritage site. Forcing a distinction between land art and landscape-as-art is inhibitive, not least because Latham’s project remains tangential to art history. Even if it were more readily included in surveys of land art, or process or conceptual art, Latham’s insistence upon a figurative reference for Niddrie Woman distinguishes it from the minimalist earthworks derived from crosses, circles, cubes, spirals and tubes. Pushing at the boundaries of sculpture, even in the ‘expanded field’, Niddrie Woman remains an intrinsically unclassifiable artwork: part scheduled monument, part site of biological diversity, part disappearing.