During the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, whether en route to Rome for the first time or making an excursion from the city as a seasoned resident, all who traversed the campagna (the countryside around Rome) did so in a state of heightened emotion and imaginative excitement. Prior familiarity with a combination of classical texts and the idealised landscape imagery of the seventeenth century established an expectation that the campagna would reveal itself to be a suitably picturesque and poetic setting for the historic scenes which had been enacted and imagined within its expanses. Encountering the contemporary reality of a bleak expanse of landscape provoked various kinds of reflection – consternation, bewilderment, denial. While this might have led to musing on the decline of great empires or encouraged the recollection of descriptions of the area in its heyday, it also prompted questions as to how and why this drastic transformation had occurred. One explanation sought the key to this in the impact of Rome’s notorious ‘bad air’ – in this sense there was recognised to be a physical and symbolic connection between the city and its surrounding countryside, which was as unwelcome as it was undeniable.

However, an important aspect of the complex of ideas and images associated with the campagna is its special place in the history of art as the site of the creation of a new form of landscape painting. In the seventeenth century the campagna became endowed with a further form of cultural prestige through the belief that it was here that Claude Lorrain and Nicolas Poussin discovered the inspiring raw material out of which they created ideal landscape painting. This association was based on an idea of Claude in particular inhabiting the landscape, savouring and absorbing its beauties, and translating them into pictorial form. This mythologisation was to be tenaciously influential on conceptions of the nature of the Roman landscape and how it was to be represented.

Approaching the campagna primarily as a resource for landscape painting’s pursuit of an ideal level of representation was in fact a very effective way of steering historical understanding away from problems which were recognised as intractable and disturbing – a landscape which was thought to produce deadly miasma, devastating what remained of its indigenous population, and threatening those who dared to pass through it.

There was much common ground between the various initiatives to investigate the root causes and identity of this pervasive but mysterious disease-producing agent and the excursions of artists in search of sites which would yield the ideal beauty promised by myth. Both were premised on the importance of what could be learnt from studying the distinctive visual appearance of the land and its inhabitants. Such scrutiny focused closely on topography and the less tangible matter of air, factors which were assumed to have shaped the physical constitution and appearance of local people.

Artists were predisposed to seek out locations that matched their expectations of a terrain defined by its purported abundance of the beautiful. Equally, cognate qualities were assumed to have been inherited by the inhabitants of this landscape from their ancient forebears. Such well-established expectations might block out the recognition of disturbing signs of chronic ill health, or else lead to jarringly discordant observations of such deterioration. The tension between these contrasting models can be explained in terms of an interplay between the topographical determinants of health and a biological notion of cultural inheritance. However, accounts of the campagna’s appearance are often curiously uninformative precisely because of the burden of expectation weighing on the moment of the travellers’ encounter, and the overwhelming sense of a discrepancy between the anticipated spectacle and the impoverished reality revealed from first-hand inspection. In both respects, the attention given to visual characteristics in the early nineteenth century was a change from more established literary conceptions of the campagna. Undertaking a tour of Latium in search of Virgil’s sites and settings, the Swiss philosopher Charles Bonstetten justified his project by claiming that previous scholars had neglected empirical observation in favour of predominantly poetic concerns (they had not looked around them but remained fixated on texts). Having taken the trouble to use his eyes, however, he found that the image of nature given by Virgil, ‘although disfigured, still exists in the landscape’ (quoique défigurée, existe encore dans le paysage).1

The campagna played a fundamental role in ideas and images of Rome, because the city was viewed and understood to be co-extensive with the surrounding landscape. This was a connection that had been politically and economically sustained in the long term by virtue of the ownership of land by a symbiotic combination of papal state and Rome’s elite families. As was repeatedly observed, the whole farmland around Rome was owned by a small number of families, who in turn paid tenant farmers to manage their property. Land was valued as a sign of status, more than as a source of income. Indeed, the conservatism of landowners to any improvement in agricultural exploitation of the campagna was usually pointed out as the crucially obstructive factor in its almost unrelieved stagnation.2 Thus, as with atmospheric contamination, and in a way which was fundamentally connected, the city was tied by deeply entrenched bonds of ownership and privilege to its hinterland.3

The question of definition extended to the interrelation of the ‘eternal city’ and the country, or more precisely involved recognising that this distinction did not apply in any familiar or simple way. For all its density of monuments ancient and modern, the city of Rome was a patchwork of archaic and majestic townscape juxtaposed with parcels of cultivation (known as the disabitato), which filled the spaces left vacant as the city had shrunk within its ancient walls. Indeed, as the nineteenth-century commentator Silvio Negro pointed out, this sense of a continuum was to remain a notable feature of Rome’s appearance until the latter part of the nineteenth century.4

This unusual configuration of urban and rural spaces gave to Rome an identity that fed into perceptions of the city in a way which was just as distinctive as the specific effects produced by individual ruins and monuments. For the philosopher Wilhelm von Humboldt, writing to his compatriot Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, it was indeed impossible to compare Rome and its surroundings with any other place; the incomparable physical presence of the city – its ‘loveliness of forms’, the ‘grandeur and simplicity of its figures, the richness of the vegetation … the definition of outlines in the translucent medium, and the beauty of the colours’ – engendered a sense of ‘pure aesthetic pleasure without a trace of desire’. So compelling was this level of experience that Humboldt condemned the excavation of half-buried buildings and viewed the idea of cultivating the campagna as a calamity.5 By contrast, in the view of Camille de Tournon, former prefect of Rome under the Napoleonic occupation, the fact that city and country were indistinguishable was the result of a local attitude of blasé neglect: ‘No nation could care less about the charms of the countryside than the Romans’.6 However, this aesthetically productive equilibrium has important consequences for our understanding of the place of landscape painting in Rome. The historian Jerome McGann’s otherwise compelling idea that Rome was unusual in being the city of Romantic significance par excellence (whereas Romantics usually sought identification with nature), fails to take account of this ambiguous situation.7

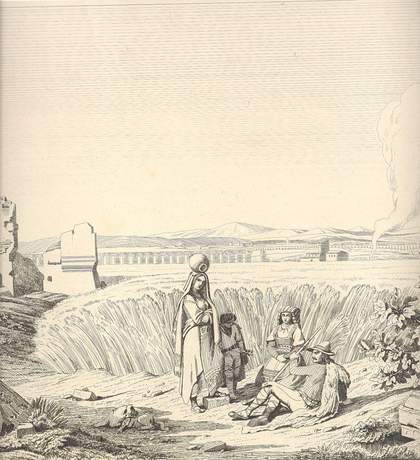

Yet ideas of mythic fertility informed a wide range of imagery, both Italian and foreign. The Roman artist Giovanni Battista Lusieri’s Extensive Landscape 1781 (fig.1) shows an interlocking view of buildings, cultivation, and open countryside, in which these different types of structure and terrain are elided together. In Lusieri’s watercolour a bourgeois couple are looking at a seated peasant; the harmoniously complementary unit of difference which they embody echoes the similar disposition of agriculture framed by a river valley in the view which extends behind them.8 Such benign conventions for showing the campagna continued through the nineteenth century almost unchanged in their ingredients. Caruelle d’Aligny’s print from 1844 (fig.2) shows a remarkably intact aqueduct running across the campagna, in the midst of which a group of peasants are placed before a solid wall of corn, with a fig sprouting vigorously from a ruin.9 Precisely the same juxtaposition of monument and cultivation is found in some photographic views of Rome from the mid-nineteenth century. Representing such contiguity as natural acts to hold at bay not only anxieties about the campagna as barren and poisoned, but also the unwelcome spectre of modernity. 10

Fig.1

Théodore Caruelle d’Aligny

Roman Campagna. View From the Ancient Road of the Tombs (detail) 1844

Etching 247 x 379 mm

Private collection

© Richard Wrigley

Fig.2

Giovanni Battista Lusieri

Extensive Landscape on a Road Above the TiberValley, North of Rome 1781

Watercolour, pen and grey ink on paper 283 x 458 mm

The British Museum, London

© Trustees of the British Museum

Emptiness could be read as a stark sign of depopulation and decline, or treated as a pleasing form of stripped down picturesqueness. However, the campagna could also be envisaged as a sanctifying frame, residually aesthetic but primarily providing a way of imagining the city as exclusively dedicated to prayer and meditation. The priest Olympe-Philippe Gerbet was scandalised by the prospect of any introduction of modern industry into the campagna, which threatened to create an ‘arena of manufacture’. In his view, Rome was and should remain ‘above all the city of the soul’, surrounded by ‘suburbs at rest, which has the desert’s majesty without its barrenness’, a space which was ‘melancholy and bare’, ‘intercepting the noises of the world around the holy city, like a great cloister for Christianity’.11

The appeal of emptiness also applied to ruined, abandoned buildings. However, in many such cases, emptiness was more a matter of an outsider’s presumption, than based on a fuller, more contextually informed understanding. In the eighteenth century, emptiness was more likely to be recuperable through a picturesque reading of the expanse of the campagna and its incidents. Consonant with the trope of coming across ruined and abandoned villas and buildings is the larger sense that the campagna was considered to be uncharted territory. There is a parallel here between historians of Rome and medical investigators, the former aiming to name and map the sites of ancient history, the latter to discover and plot a topographical answer to the causes of bad air as a means to improve public health.12 More general scientific investigation was also undertaken in the form of natural history, and the cataloguing of flora and fauna. 13

A sense of emptiness could also have the effect of prompting a desire to isolate artistic characteristics which then stand in for the lack of other features. Eugène Pelletan’s claim that the Popes had deliberately maintained the desolation of the Roman countryside so as to increase the drama of visitors’ sense of encounter with a beautiful and sanctified city was vigorously rebuffed by the parliamentarian Corrado Tommasi-Crudeli. 14 The Scottish painter David Wilkie commented that: ‘In approaching [Rome], we had to pass an immense plain, uncultivated, unwholesome, and yet beautiful’.15 That beauty could be substantiated, and indeed aggrandised, by calling to mind artists’ names. Wilkie’s description shifts into recollection: ‘in the blue distance [we saw] some of those mountains one is familiar with in the pictures of Claude. From Albano to this place [Velletri] we passed through scenes that realise all that Salvator Rosa conceived or Poussin drew’.16 Similarly, J.M.W. Turner noted ‘The first bit of Claude’ on his way to Rome in 1819,17 and a ‘Wilson-Brown Campagna’ once he had arrived.18 The invocation of artists’ names is a way to distance the viewer from any sense of discomfort, but yet also to identify with and lay claim to the prospect. It is as if the gaze needs to be focused on distant mountains, which occupy a realm above the more sordid conditions immediately underfoot. The painter Ippolito Caffi’s 1847 views of the campagna from a balloon seem to work in the same way, celebrating the aesthetic pleasures to be had by rising above the glowing but sinister evening mists.19

This tension in the moment of viewing is inherent in the way the area was named. Charles Bonstetten bluntly challenged the accuracy of the name: the campagna of Rome ‘has been called countryside most likely out of politeness, for in all directions this is no more than a diseased and often sterile wetland’.20 In doing so he hints at the way Rome was bound to its surroundings by the immaterial but inescapable presence of bad air. The sense of intervisibility between the city and its campagna was also reinforced by an all too seamless atmospheric connectedness. The harrowing contrast of the campagna with the prospect of the great city was rendered not merely a dramatic anti-climax, but was potentially life-threatening. This was poetically alluded to by the English writer William Hazlitt, when he asked why artists would want to remain in Rome at all: he conceded that the entrancing experience of being able to watch ‘the morning mist rise from the Marshes of the Campagna and circle round the Dome of St Peter’s’ might persuade some that this was enough to offset the city’s squalor and disease which the reference to marsh mist might otherwise seem to reinforce.21 The novelist Lady Morgan was a connoisseur of such symbolic conflicts: ‘St Paul’s and St John Lateran rise on the dreary frontiers of the infected deserts they dominate, like temples dedicated to the genius of the mal-aria’.22 Later in the century, it was precisely the bareness of the ground which was blamed by the French doctor Léon Colin for giving unimpeded access to the city to noxious marsh vapours coming from far and near.23

Whether the collapse of the Roman Empire had led to physical degradation of the campagna, or rather that indigenous bad air was to blame for the destruction of a wealthy and sophisticated culture, was a moot point. However, the problem was certainly recognised as having existed in antiquity. The science historian Robert Sallares has recently provided an authoritative account of awareness of and attitudes to this in classical texts, informed by a modern understanding of malaria. By virtue of this literary evidence, later commentators were able to carry on an extended debate on the changing condition of the ancient and modern Roman landscape. The nineteenth-century historian of Rome Jean-Jacques Ampère, for example, sought to establish a physical context for the evolution of early Roman history. Indeed, that Roman culture was too successful in its struggle with an inhospitable climate and environment was for him further evidence of the indomitable spirit of these early generations of Romans.24

The campagna was thus the antithesis of conventional ideas of rural retreat where, in the writer Arthur Young’s words, ‘the peace-loving man has retired from the tumult of cities and centres of intrigue, to devote himself to cultivating the land’.25 It was a space seen as empty, and forbidding; even to antiquarians it was little known. Rather it was a territory which predominantly encouraged quick traversal, cautious if not distant inspection, accompanied by melancholy reflections perhaps alleviated by scientific curiosity. This sense of circumspection can be linked to the way views of the campagna are often constructed as if looking out from a protective screen of buildings or vegetation. The celebrated oil sketches of P.H. Valenciennes, renowned as a reformer of landscape painting, exemplify this tendency to maintain a certain distance, at once aesthetic and precautionary. Seen from this perspective, these studies retain their sense of being products of a desire to explore Rome as a source of landscape imagery, but express that engagement precisely through setting the motif at one remove from the space occupied by the artist. In this light, the use of screening elements has a function beyond that of compositional equilibrium, and although Valenciennes himself does not address the problem of the campagna’s bad air in his comments on Rome as a place for the education of landscape artists, this could be seen as expressing a form of cautious equivocation. We could compare this pictorial device to the quintessential Claudeian motif of trees screening a vista: eighteenth-century enthusiasm for this aspect of Claude’s campagna imagery might also have been informed by the idea that trees acted as a cleansing filter, thereby counteracting the threat of poisoned air, as well as in pictorial terms modulating the intensity of light effects.